Abstract

This study investigates the level and predictors of life satisfaction in people living in slums in Kolkata, India. Participants of six slum settlements (n = 164; 91% female) were interviewed and data on age, gender, poverty indicators and life satisfaction were collected. The results showed that the level of global life satisfaction in this sample of slum residents did not significantly differ from that of a representative sample of another large Indian city. In terms of life-domain satisfaction, the slum residents were most satisfied with their social relationships and least satisfied with their financial situation. Global life satisfaction was predicted by age, income and non-monetary poverty indicators (deprivation in terms of health, education and living standards) (R2 15.4%). The current study supports previous findings showing that people living in slums tend to report higher levels of life satisfaction than one might expect given the deprivation of objective circumstances of their lives. Furthermore, the results suggest that factors other than objective poverty make life more, or less, satisfying. The findings are discussed in terms of theory about psychological adaptation to poverty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

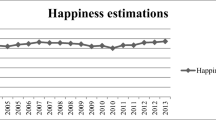

Over the past decades, life satisfaction has received an increasing amount of attention. Life satisfaction refers to the cognitive evaluation of the quality of one’s life as a whole (global life satisfaction), or of specific life domains (domain satisfaction) (Myers & Diener, 1995). Numerous studies have emphasized the links of life satisfaction with several benefits such as health, longevity, social relationships, prosociality and productivity (de Neve et al., 2013; Diener & Tay, 2012; Heintzelman & Tay, 2017; Lyubomirsky et al., 2005). Given its benefits, life satisfaction has become more and more relevant, both for individuals and policymakers (Maccagnan et al., 2019). It is, therefore, not surprising that over the past decades there has been an extraordinary amount of effort put in the assessment of life satisfaction, both on the national and the individual level. For instance, since 2005, the Gallup World Poll has collected data on life satisfaction of large samples in more than 160 countries in over 140 languages (Helliwell et al., 2019). This allows for between-country comparison on life satisfaction as well as analysis of change in life satisfaction within countries over time.

The positive effects of life satisfaction highlight the importance of improving our understanding of its antecedents and what can be done to improve it within society for psychology, public health and policy makers in these fields. One of the most interesting questions with regard to life satisfaction is the extent to which life satisfaction is influenced by external and material conditions versus personal factors (including the attitude towards these conditions). A more specific question is “What are the conditions for a satisfied life: to what extent needs life to be trouble-free?”. Available evidence shows that the average ratings of life satisfaction are lower in nations and people who are afflicted by serious hardship (e.g., war, violence personal adversity and loss) than in nations/people that are not. On the other hand, evidence obtained in various settings shows that people can be quite happy and can even thrive in spite of difficult circumstances (Veenhoven, 2005). These paradoxical findings make clear that there is more to learn about life satisfaction, in particular in people confronted with serious hardship.

The current study has been carried out in India, which is extreme in terms of population density and wealth inequality. Moreover, India is facing a large number of other social issues such as caste system, gender inequality, child labor, illiteracy, poverty, religious conflicts, and more. It represents, therefore, a particularly interesting setting for research on life satisfaction. This study focuses on life satisfaction of people living in a very low resource setting i.e., in urban slums in India where hardship is bounteous, which remains a vastly understudied group.

Growth and Inequality in India

India is one of the most culturally, linguistically, and genetically diverse countries in the world. It consists of 28 states and 9 union territories, has 22 official languages and over a thousand dialects, six major religions and over 4000 castes (Venkata Ratnam & Chandra, 1996). It is a country of opposites: on the one hand, India is known for its immense population and population growth, its pollution and poverty (Chandramouli, 2011; Khilnani & Tiwari, 2018; Thorat et al., 2017). On the other hand, however, it is a country of opportunities, where the economy and technological development are thriving at enormous speed: India has the second biggest annual GDP growth in the world and the national GDP grew about 260 percent from 2000 to 2019 (The World Bank, 2021). Regardless of the economic growth and newly achieved wealth in India, the wealth inequality in the country has increased rapidly since 1991. Where the wealth of Indian billionaires increased by almost 10 times over the last decade, the poorest half of the population saw their wealth rise by just 1 percent (Himanshu, 2018). Taking into consideration that about 22 percent—270 million people—of the total population in India is living below the poverty line (Reserve Bank of India, 2015), economic wealth is far out of sight for a significant number of people.

Throughout the twentieth century distress and poverty in the rural areas in India resulted in a huge influx of refugees and migrants into urban areas which has led cities to grow rapidly since the 1950s (Singh, 2016). The rapid urbanization resulted in lack of space and acceptable housing which culminated in the emergence of slum settlements in and outside the city (Ray, 2017). Although the living conditions in most slums are generally bad, there is significant variation between slums for example with regard to available facilities, identity groups (e.g., Hindu versus Muslim) and reported incomes (Lange, 2020). Another source of variability between slums is legal status. More than half of all slums in India are not recognized by the government (Nolan et al., 2017). These slums, also known as non-notified slums, are more deprived in access to basic services and living security than notified slums and people living in these slums live under a constant threat of eviction (Ray, 2017). This deprivation of living security may have negative consequences. Evidence from a systematic review revealed that threat of eviction is related to lower mental and physical health such as depression, anxiety, psychological distress, suicide, elevated blood pressure and child maltreatment (Vásquez-Vera et al., 2017). Even with significant variation in living security, facilities and ethical/religious demographics, slums are often deprived with respect to economic, social and living conditions (Ray, 2017) and most people would consider these places as unsuitable for living. When it comes to well-being, one might expect that a population of this enormous magnitude, living in these deprived circumstances, is less happy as their more privileged, Indian counterparts. But are the poor really as dissatisfied with life as one might expect them to be?

Poverty and Life Satisfaction in Urban Slum Settlements

The idea that material conditions (e.g., money) matter to happiness has inspired many scholars to explore the relationship between income and life satisfaction (e.g., Tay et al., 2018). The results of these studies show that income contributes to life satisfaction. For instance, the World Happiness Report 2019 found that higher national incomes are linked with higher life satisfaction of citizens, indicating that on average, those living in richer countries are happier than those living in poorer countries (Helliwell et al., 2019). The results from within-nation studies show however that the positive correlation between income and life satisfaction varies. The highest correlations between income and life satisfaction were found in low-income groups living in economically less developed countries. Yet, this relationship remains weak, which implies that income explains little of the variance in life satisfaction (Howell & Howell, 2008).

Despite the plethora of research on life satisfaction, few studies have focused on life satisfaction in people living in extreme poverty. Traditionally, poverty has been conceptualized as economic deprivation. Yet, since the 1980s, the definition of poverty has broadened from a monetary approach (measured by income only) to a multidimensional approach which takes into account other factors related to basic needs such as housing, sanitation, and education. Previous studies (Bag & Seth, 2018; Ki et al., 2005) showed that a multidimensional assessment of poverty more completely captures the phenomenon and it is now widely recognized that multidimensional poverty is a richer concept than the traditional unidimensional monetary approach (Asselin, 2009). The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), constructed by (Alkire & Foster, 2011), is a methodology to measure poverty corresponding to the three dimensions: Health, Education and Standard of Living (Table 1). It gathers different household-level information with the use of ten indicators and captures whether households suffer deprivation according to the dimensions. Most of the research on poverty and life satisfaction has focused on the monetary approach solely, whereas the current research builds on this by including non-monetary indices of poverty.

The Current Research

The purpose of this study is to examine life satisfaction and its predictors in the context of extreme poverty. The study is set in Kolkata which is one of the largest cities in India. Out of a total population of about 4.5 million people (Government of India, 2011), almost a third of its inhabitants lives in slums (Ray, 2017) showing the importance of carrying out research in this particular population.

The current study aims to replicate the work of (Biswas-Diener & Diener, 2001) who performed a study on life satisfaction among the poorest inhabitants of Kolkata in 2001. Their results showed that their sample, consisting of pavement dwellers, slum residents and sex workers, scored slightly negative on global life satisfaction. It is noteworthy, however, that the level of global life satisfaction in slum residents (which was significantly higher than in the other disadvantaged groups) almost matched the level of global life satisfaction in Indian students. Moreover, it was found that the participants were satisfied with most of the assessed life domains. These findings suggest that certain communities and cultures, although poor, may enjoy a relatively high level of life satisfaction.

Nearly 20 years have passed since then and during that time India has seen rapid changes. Economic growth has combined with actions by government agencies and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) to address the newly revised target of the first Sustainable Development Goal (SDG): “to end poverty in all forms everywhere” (United Nations, 2015). Yet, despite these efforts, the gap between the rich and the poor has widened and still a substantial proportion of the population lives below the poverty line (World Bank Group, 2020). After 20 years of change it might be time to investigate the life satisfaction of the extreme poor again.

The current study focuses on the level and determinants of life satisfaction of people living in slums in Kolkata. In line with the study by Biswas-Diener and Diener (2001) the assessment of global life satisfaction will be complemented with measures of life-domain satisfaction (e.g., income satisfaction, health satisfaction). What is new is that the study does not solely focuses on monetary poverty as a predictor of life satisfaction, but also takes the explanatory power of multidimensional aspects of poverty into account. Last, as 59% of the slums in India are non-notified (Nolan et al., 2017), the role of fear of eviction as a predictor of global life satisfaction will be explored.

The specific aims of this study are:

-

1.

To document the level of life satisfaction (global and domain-specific) of people living in urban slums in Kolkata, India.

-

2.

To test whether there is a difference between the different domain satisfactions (social relationships, physical environment, physical health, psychological health and financial situation) in people living in urban slums in Kolkata, India.

-

3.

To compare the level of global life satisfaction of slum residents with global life satisfaction measured in a representative sample from the general population of another large Indian city (Delhi) as measured by the Gallup Poll.

-

4.

To examine age, gender, poverty indicators (monetary, multidimensional) and fear of eviction as predictors of global life satisfaction.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants

The present study, conducted by Calcutta Rescue in 2019, is part of a larger cross-sectional research project on poverty in urban slums (Lange, 2020). Calcutta Rescue is a medium-sized NGO that focuses on supporting the slum communities in Kolkata which are most poorly served by the local and national government. Participants were eligible for this study if they were 18 years and older and resided in one of the six different slum settlements in the urban area of Kolkata in India (see Sect. Slum Selection and Sampling Method). Participation was voluntary and participants did not receive any financial compensation for their participation. The informed consent was read to (or by) all participants, dependent on whether the respondent was able to read and write. In case the respondent was illiterate, the informed consent was explained verbally, and a literate family member was asked to sign on behalf of the participant, or a thumbprint was obtained from the respondent.

Slum Selection and Sampling Method

A slum area is defined broadly in line with the 1997 Indian Compendium of Environment Statistics as groups of 25 or more poor-quality dwellings (Kundu, 2003). The slums to be sampled were all part of the operational area of Calcutta Rescue and were distributed across the city. Part of the slum settlements was unregistered and part was registered (legal). The slums varied in population size: based on the average household size and the number of households, the estimated population numbers vary between 132 (Baranagar) and 1107 (Local Bustee). Following Kundu’s (Kundu, 2003) study on slums in Kolkata, a systematic sampling method was used. According to this method, an equal distribution of 15 percent of the households is considered as a minimum sample size. The current study aimed at sampling/interviewing 20 percent of the slum or 30 households, whichever was bigger. In order to get an equal sample across the whole slum, the area was mapped and households were counted prior to data collection. Every fifth household (20 percent) was asked to participate. Data were collected during the day and the structured interviews lasted between 25 and 50 min. Interviews were conducted in the participant’s home with the researcher and a translator, who was fluent in English, Bengali and Hindi. The data were recorded on smartphones in (KoBoToolBox, 2019), an online data collection system for challenging environments.

Measures

Life Satisfaction

Global life satisfaction was assessed using Cantril’s ladder (Cantril, 1965). Respondents were asked to evaluate their satisfaction with their lives as a whole using the Ladder Scale; an illustration of a ladder which represents their life, 1 being their worst possible life and 8 being their best possible life. Participants’ domain satisfaction was measured with 5 single items assessing participants’ satisfaction with different life domains: social relationships, physical environment, physical health, psychological health and financial situation. The items were derived from the WHO questionnaire on Quality of Life (WHOQoL Group, 1994) (e.g., In general, how satisfied are you with your social relationships) using a 5-point Likert scale format. The one-to-five rating was depicted on a piece of paper ranging from an extreme frown (1) to an extreme smile (5), similar to earlier research by Biswas-Diener and Diener (Biswas-Diener & Diener, 2001). Higher scores reflect higher levels of life satisfaction.

Predictors of Life Satisfaction

Socio-Demographic Variables

Socio-demographic variables included age and gender (female = 0, male = 1).

Poverty

Poverty was measured in two ways: using both monetary (income) and non-monetary approaches (MPI).

Income

Monthly income per capita was calculated based on the monthly household income divided by the number of household members.

Multidimensional Poverty

Table 1 illustrates the assessment of multidimensional poverty based on the Multidimensional Poverty Index (Alkire & Santos, 2014; UNDP, 2020). The MPI identifies deprivations at the household and individual level across three dimensions and 10 indicators: Health (child mortality, nutrition), Education (years of schooling and school enrollment) and Standard of Living (water, sanitation, electricity, cooking fuel, floor, assets). As shown in the table each of the three dimensions is equally weighted (one third each), though the individual indicators receive different weights. Weights are thus applied to each of the indicators, which are then summed up to a total MPI score. The total MPI score for each person lies between 0 and 1. A higher score represents a higher level of multidimensional deprivation.

Fear of Eviction

In addition to the above-mentioned MPI-indicators, information was gathered about whether the participant experienced a fear of being evicted (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Statistical Analysis

An a priori power analysis was conducted through G power (Faul et al., 2009) (α = 0.05, power = 0.80, medium effect sizes) to calculate the required sample size. Descriptive statistics (medians, means, standard deviations, percentages) were used to describe the data and to address the first research aim. Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test the significance of the mean differences between the five life domains (research aim 2). The Greenhouse–Geisser adjustment was used to correct for violation of assumption of sphericity, which is common in ANOVA within-subject analyses. Effect sizes (ES) were based on Cohen’s η2 (ES: 0.01 = small, 0.06 = medium, 0.16 or larger = large) (Draper, 2011). To address the third research aim we compared the sample mean with the mean life satisfaction score of a representative sample of the general population in Delhi as measured by the Gallup Poll (De Neve & Krekel, 2020). We first homogenized the responses for the Cantril’s ladder of our study (measured on a 1–8 response format) with those obtained by the Gallup Poll (the Cantril’s ladder in the Gallup Poll uses a 0–10 response format) using the linear stretch method (de Jonge et al., 2014). The one sample t test was used to determine whether the Kolkata slum sample mean significantly differed from the Delhi general population mean. Effect sizes were based on Cohen’s d (ES: 0.2 = small, 0.5 = medium, and 0.8 or larger = large; Draper, 2011). The fourth research aim was tested by applying hierarchical multiple regression analysis (method enter) in which age and gender were entered in the first step, income per capita in the second step and the MPI and living security in the third step. Effect sizes were based on R2 (1% small, 9% medium, 25% large; Draper, 2011). Statistical significance (alpha) was assessed at the 0.05 level.

Results

Sample Characteristics

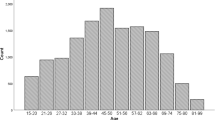

The characteristics of the sample (N = 164) are described in Table 2. As shown in the table, the sample was predominantly female (90.9%). Almost two-thirds of the sample were literate and from a Hindu background. The participants were long-term residents who had, themselves or their families, lived in the slum settlement for decades (not shown in the table). Almost two-third of the households was deprived in living security (64.6%). Most participants were able to meet daily needs. The results showed that the participants were most deprived in terms of housing, assets and living security.

The Level of Life Satisfaction in Kolkata Slum Residents

The descriptive statistics for global and domain-specific life satisfaction (research aim 1) are presented in Table 3. With regard to research aim 2, the results of the repeated measures ANOVA with a Greenhouse–Geisser correction demonstrated a significant difference between the mean satisfaction levels across the different life domains (F(3.61, 580.69) = 21.83, p = 0.000, partial η2 = 0.12). A Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc analysis revealed that the participants reported significantly lower satisfaction in the financial domain than in the other life domains, whereas their ratings of satisfaction in the social domain were significantly higher than those of the other life domains (all p < 0.05). The satisfaction levels of the living environment domain and health domains (physical and psychological) did not significantly differ from each other (all p’s > 0.05).

Life Satisfaction: Kolkata Slum Residents vs. the General Population

Regarding research aim 3, the results of the one sample t test showed the mean global life satisfaction score measured in Kolkata’s slum population (M = 4.27, SD = 3.19) did not significantly differ from the average global life satisfaction score of 4.01 of people living in Delhi (De Neve & Krekel, 2020). The difference, 0.26, 95% CI [-0.24 to 0.75], t(160) = 1.02, p = 0.31, represented an effect size of d = 0.08.

Prediction of Life Satisfaction

Table 4 shows the relationships between (non)monetary indices of poverty, fear of eviction and global life satisfaction (controlled for age and gender) (research aim 4). The results of the bivariate analyses (presented in the second column of the table) revealed that lower age, higher income, lower levels of multidimensional deprivation (MPI scores) and lower scores on fear of eviction were associated with higher levels of global life satisfaction. When entered in the multivariate model (presented in columns 3–5 of the table) the association between fear of eviction and global life satisfaction was no longer significant. The MPI (reflecting the non-monetary approach to poverty) accounted for additional variance (above income). The full model explained 15.4% of the variance (F(5, 150) = 5.46; p = 0.00) in global life satisfaction.

Discussion

This study investigated the level and predictors of life satisfaction of people living in slums in Kolkata, India. In line with previous research, it was found that slum residents were less dissatisfied with their lives than one would have held given the dire living conditions of these people. For the prediction of global life satisfaction, income (monetary poverty) was complemented with the Multidimensional Poverty Index (non-monetary poverty) and fear of eviction. The results showed that not only income but also non-monetary indices such as education, living standards and fear of eviction are important correlates of life satisfaction of people living in slums.

The level of global life satisfaction observed in this study was comparable to those measured in a representative sample from Delhi, another large metropole in India. Although counterintuitive, our finding of a relatively high level of life satisfaction in a marginalized group is not new. For example, in a study among the poorest of the poor in South Africa, it was found that landfill waste pickers scored higher on life satisfaction than the national average (Blaauw et al., 2020). The same study found that there was a significant group of waste pickers who were very satisfied with their lives. Our findings also resemble those reported by Biswas-Diener and Diener (2001) and Cox (2012) who found slightly positive global life satisfaction in urban slum residents and dump dwellers in Kolkata, India and Managua, Nicaragua, respectively.

With regard to domain satisfaction, the slum residents were fairly satisfied with three of the five life domains assessed in this study i.e., their social relationships and health (physical and psychological). They were least satisfied with their financial situation and physical environment. Similar findings have been reported in previous studies addressing domain satisfaction in poor populations (Biswas-Diener & Diener, 2001; Cox, 2012; Sharma et al., 2019). Various scholars have emphasized the importance of social ties for well-being (Diener & Seligman, 2004), especially in poor populations (Boswell & Stack, 1975; Domínguez & Watkins, 2003; Henly, 2007). Social connectedness has been associated with access to various forms of social support and cognitive processes associated with subjective well-being such as life satisfaction, enhanced self-esteem, self-worth, purpose and meaning in life (Thoits, 2011). Social ties may serve as a private safety net, a poor family can fall back on in times of need (Edin & Lein, 1997).

In terms of prediction, higher levels of life satisfaction were related to age, income and deprivation. Due to shared variance with the MPI, fear of eviction did not explain unique variance in life satisfaction. Specifically, younger residents and those with higher incomes and lower scores on the MPI reported higher levels of global life satisfaction. Our findings regarding the relationship between age and global life satisfaction related to those reported by (Cox, 2012) who examined age as a predictor of life satisfaction in poor populations in Nicaragua and data from the Gallup World Poll (Fortin et al., 2015). Our results are in line with previous work which emphasized the role of income in life satisfaction (Whitaker & Moss, 1976). Moreover, the income-life satisfaction relationship in this study was comparable to the average r effect size of 0.28 computed for low-income samples in developing countries in Howell and Howell’s (2008) meta-analysis. The current study also confirms the results of research reporting a negative relationship between the MPI and life satisfaction in people living in the poorest districts of Peru (Mateu et al., 2020) and India (Strotmann & Volkert, 2018).

Overall, data from several studies suggest that slum residents in developing countries, such as India, are more satisfied with their lives than one would expect based on their living conditions. This contradicts the common-sense belief that poor people are unhappy by definition. Such judgment is, however, an illustration of the “focusing illusion” (Schkade & Kahneman, 1998) which has received a lot of attention in the literature on life satisfaction. The “focusing illusion” takes place when individuals exaggerate the importance of a single factor (e.g., living circumstances or material wealth) on well-being. Going beyond the stereotype that poverty equates unhappiness may provide a different picture. Research suggests that people living in poverty may consider different aspects of life important for their well-being than people from a more affluent background. For example, extremely poor Nicaraguan garbage dump dwellers in the study by (Vásquez-Vera et al., 2017) reported that their happiness did not emerge from job status or income, but rather from meaningful interactions and relationships with others.

Moreover, the explanatory power of objective poverty (as measured by income and the MPI) for life satisfaction was limited. This is in line with a vast array of research showing that objective life conditions do explain only a minor part of inter-individual differences in life satisfaction (Argyle, 2013; Diener & Biswas-Diener, 2002). How hardship is perceived on the other hand, may be of much bigger importance for the appraisal of one's life (Veenhoven, 2005). Poverty is a subjective feeling, which means that people defined as poor by objective standards do not necessarily have to feel poor. Indeed, results from a recent meta-analysis (Tan et al., 2020) indicate that life satisfaction has a stronger link to subjective socio-economic status than objectively measured income or education.

Our findings could be interpreted in the light of the human capacity to adapt to environmental demands. Adaptability is a self-regulatory resource which allows individuals to adjust to good and bad phenomena by altering their standards, thoughts, behaviors and emotions to the requirements of situations at hand. Adaptability can help prevent or mitigate the negative impact of challenge and adversity on well-being (Carver & Scheier, 2001). Following the multiple discrepancies theory (Michalos, 1985), life satisfaction relates to the discrepancy between what one has and what one wants (desire discrepancy) and what relevant others have (social comparison discrepancy) (Brown et al., 2009). Perceived negative discrepancies between one’s standards and one’s actual situation have a negative impact on life satisfaction. In the context of slums, perceived discrepancies between what one has (slum dwelling) and what one wants (a decent house), or what one has (no income) and what relevant others have (improvement in daily wage) could be a source of dissatisfaction with life. Effects of perceived negative discrepancies can be counterbalanced, however, by self-regulatory discrepancy reducing processes such as choosing a relevant reference group for social comparison and lowering aspirations (Carver & Scheier, 2001).

Regarding social comparison, it has been found that people have a natural tendency to compare themselves with others (Festinger, 1954), in particular with relevant reference groups such as people with a similar ethnicity, background or occupation (Khaptsova & Schwartz, 2016). In the case of low status or minority groups, several studies found that exposure to a successful referent from a low-status group is more pleasant and meaningful than exposure to a referent from a high-status group (Blanton et al., 2000; Leach & Smith, 2006; Mussweiler et al., 2000). This highlights the value of identifying local champions (e.g., former classmates who have excelled in school or sports) to serve as role models for young people living in low resource settings (Kearney & Levine, 2020).

Lowering aspirations is another discrepancy reducing mechanism. This has been observed in deprived neighborhoods including two Kenyan urban slums (Kabiru et al., 2013) where the constraints of the environment had a leveling effect on young people’s occupational and educational aspirations. Similar findings have been reported for youth in disadvantaged neighborhoods in the US and Scotland (Furlong et al., 1996; Stewart et al., 2007). In the case of Kolkata, it is possible that slum residents compare themselves mostly to people within their community and set their aspirations and goals accordingly. Indeed, research has found that expectations of life and oneself are influenced by one’s relative position and social norms within one’s community (Knight et al., 2009). Both social comparison and lowering aspirations are self-protective strategies that may help to ensure subjective well-being in situations in which the remediation of disadvantage is beyond the scope of personal control (Blanton et al., 2000; Leach & Smith, 2006; Mussweiler et al., 2000). Unfortunately, such strategies may also lead to aspiration traps where people under-aspire in occupational and educational goals, thereby contributing to the intergenerational transmission of poverty (Flechtner, 2014).

This study is one of the few examining life satisfaction in people living in a very low resource setting such as an urban slum in India. Other strengths are the relatively large sample size and the inclusion of non-monetary indicators of objective poverty as predictors of life satisfaction. The use of non-monetary poverty indices such as the MPI in life satisfaction research is relatively new. This approach is in line with new perspectives on measuring the material situation (combining income with a direct measure such as a deprivation index) (Christoph, 2010). Our results (showing an incremental contribution by the MPI) suggest the added value of combining monetary- (income) and non-monetary measures (the MPI) when analyzing the relationship between the material situation and life satisfaction.

Nevertheless, some limitations merit attention. First of all, this study only included objective measures of poverty. The addition of subjective measures of poverty (the individual’s perception of his/her financial and material situation) could have offered a more complete picture of the poverty-life satisfaction relationship. Secondly, the cross-sectional design of this study failed to establish causality. Thirdly, because the interviews were conducted in person and in the participants’ homes, which gave the possibility onlookers or family members meandering in earshot of the survey being asked, the research design could have been prone to social desirability bias (Tourangeau et al., 2000). Finally, the fact that the sample was predominantly female was most likely caused by the fact that interviews were conducted during the day when women were more typically at home. This may limit the generalization of the results. However, a recent meta-analysis of 281 samples (Batz-Barbarich et al., 2018) did not show significant gender differences in life satisfaction. In addition, the study of Biswas-Diener and Diener (2001) which was conducted in a comparable sample in Kolkata showed no significant differences in life satisfaction between men and women. This gives us no reason to believe that the unequal sample sizes in gender influence outcomes in life satisfaction in the current study.

The results of the present study highlight the need for further research. A mixed methods design adding qualitative approaches to the assessment of life satisfaction could illuminate a more holistic and contextual understanding of slum residents’ perceptions and experiences in daily life (Camfield et al., 2009). Secondly, in addition to measures of objective poverty, further research should also include subjective indices of poverty as this accounts for a better prediction of life satisfaction compared to objective poverty measures (Tan et al., 2020). Lastly, it would be valuable to learn more in-depth about psychological processes underlying life satisfaction of people living in slums such as social comparison and aspirations.

In terms of clinical practice, practical assistance such as slum upgrading should be complemented with efforts to improve the life satisfaction of slum residents. Research highlights the benefits of a positive mindset including a less pronounced stress response (Smyth et al., 2017), better role functioning (Moskowitz et al., 2012) and more efficient decision making (Isen, 2000). This has been explained by research showing that a positive mental state helps building coping resources by broadening the individual’s attention and action repertoire (Fredrickson, 2004). Other research has shown that the presence of a positive mindset buffers against the negative psychological impact of adversity (Suldo & Huebner, 2004; Veenhoven, 2008). Psychological interventions aimed at improving the mental health of people living in slums should thus not exclusively focus on the reduction in problems but also on the enhancement of positive mental states. The few studies that have examined the effect of individual and group-based positive psychology interventions in disadvantaged populations in developing countries show promising results, including a large increase in life satisfaction, positive affect, positive thoughts, generalized self-efficacy and reductions in self-reported symptoms of depression and negative affect (Ghosal et al., 2013; Sundar et al., 2016). Efforts to improve the life satisfaction of the slum residents may thus be worthwhile to consider, as it may help them deal with the harsh reality of life.

Conclusion

The common belief that poor people are unhappy by definition is challenged by the results of this study on life satisfaction in urban slums in India. The findings of the study show that the slum residents in Kolkata scored comparable to the general population in terms of global life satisfaction (evaluation of the quality of life as a whole) and that they found satisfaction in other life domains than finances and their living environment. Moreover, in terms of prediction, objective poverty indicators explained only a minor part of the variance in life satisfaction. This suggests that it is not correct to determine a person’s life satisfaction on the basis of income and other socioeconomic variables alone and that other factors such as the appraisal of one’s life should be taken into account when examining life satisfaction. A suggestion for future studies is to include measures of subjective poverty and other personal individual difference factors when measuring the impact of poverty on life satisfaction.

Availability of data and material

Code availability

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26.0

Abbreviations

- ES:

-

Effect size

- GDP:

-

Gross domestic product

- MPI:

-

Multidimensional poverty index

- NGO:

-

Non-governmental organization

- SDG:

-

Sustainable development goal

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Alkire, S., & Foster, J. (2011). Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. Journal of Public Economics, 95(7–8), 476–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.11.006

Alkire, S., & Santos, M. E. (2014). Measuring acute poverty in the developing world: Robustness and scope of the multidimensional poverty index. World Development. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.01.026

Argyle, M. (2013). The psychology of happiness. Routledge. https://www.cis.org.au/app/uploads/2015/04/images/stories/policy-magazine/2002-autumn/2002-18-1-richard-tooth.pdf

Asselin, L.-M. (2009). Analysis of Multidimensional Poverty (Vol. 7). Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0843-8

Bag, S., & Seth, S. (2018). Does it matter how we assess standard of living? Evidence from Indian slums comparing monetary and multidimensional approaches. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1786-y

Batz-Barbarich, C., Tay, L., Kuykendall, L., & Cheung, H. K. (2018). A meta-analysis of gender differences in subjective well-being: Estimating effect sizes and associations with gender inequality. Psychological Science, 29(9), 1491–1503. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618774796

Biswas-Diener, R., & Diener, E. (2001). Making the best of a bad situation: Satisfaction in the slums of Calcutta. Social Indicators Research, 55(3), 329–352. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010905029386

Blaauw, P., Pretorius, A., Viljoen, K., & Schenck, R. (2020). Adaptive expectations and subjective well-being of landfill waste pickers in South Africa’s free state province. Urban Forum. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-019-09381-5

Blanton, H., Crocker, J., & Miller, D. T. (2000). The effects of in-group versus out-group social comparison on self-esteem in the context of a negative stereotype. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.2000.1425

Boswell, D., & Stack, C. B. (1975). All our kin: strategies for survival in a black community. Man, 10(1), 160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2801228

Brown, K. W., Kasser, T., Ryan, R. M., Alex Linley, P., & Orzech, K. (2009). When what one has is enough: Mindfulness, financial desire discrepancy, and subjective well-being. Journal of Research in Personality. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.07.002

Camfield, L., Crivello, G., & Woodhead, M. (2009). Wellbeing research in developing countries: reviewing the role of qualitative methods. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9310-z

Cantril, H. (1965). The pattern of human concerns. The British Journal of Sociology, 18, 212.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (2001). On the Self-Regulation of Behavior. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139174794

Chandramouli, C. (2011). Census of India 2011. Provisional Population Totals. New Delhi: Government of India. https://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011-prov-results/data_files/India/paper_contentsetc.pdf

Christoph, B. (2010). The relation between life satisfaction and the material situation: A re-evaluation using alternative measures. Social Indicators Research, 98(3), 475–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9552-4

Cox, K. (2012). Happiness and unhappiness in the developing world: life satisfaction among sex workers, dump-dwellers, urban poor, and rural peasants in Nicaragua. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-011-9253-y

de Jonge, T., Veenhoven, R., & Arends, L. (2014). Homogenizing responses to different survey questions on the same topic: Proposal of a scale homogenization method using a reference distribution. Social Indicators Research, 117(1), 275–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0335-6

de Neve, J., Diener, E., Tay, L., & Xuereb, C. (2013). The objective benefits of subjective well-being. CEP Discussion Paper No 1236, 1236, 1–35. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/51669/1/dp1236.pdf

de Neve, J.-E., & Krekel, C. (2020). Cities and happiness: a global ranking and analysis. The World Hapiness Report 2020, pp. 46–65. https://worldhappiness.report/

Diener, E., & Tay, L. (2012). A scientific review of the remarkable benefits of happiness for successful and healthy living. Happiness: Transforming the Development Landscape, 90–117. http://www.bhutanstudies.org.bt/publicationFiles/OccasionalPublications/Transforming Happiness/Chapter 6 A Scientific Review.pdf

Diener, E., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2002). Will money increase subjective well-being? Social Indicators Research, 57(2), 119–169.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00501001.x

Domínguez, S., & Watkins, C. (2003). Creating Networks for Survival and Mobility: Social Capital Among African-American and Latin-American Low-Income Mothers. Social Problems, https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2003.50.1.111

Draper, S. (2011). Effect size. https://www.psy.gla.ac.uk/~steve/best/effect.html

Edin, K., & Lein, L. (1997). Work, welfare, and single mothers’ economic survival strategies. American Sociological Review, 62(2), 253–266. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657303

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

Flechtner, S. (2014). Aspiration traps: When poverty stifles hope. Inequality in Focus, 2(4), 1–4.

Fortin, N., Helliwell, J., & Wang, S. (2015). How Does Subjective Well-being Vary Around the World by Gender and Age? In Helliwell JF, Layard R, & Sachs J (Eds.), World Happiness Report 2015 (2015th ed., pp. 42–75). Earth Institute, Columbia University. https://www.academia.edu/download/46704794/WHR15.pdf#page=44

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden–and–build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1512

Furlong, A., Biggart, A., & Cartmel, F. (1996). Neighbourhoods, Opportunity Structures and Occupational Aspirations. Sociology, https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038596030003008

Ghosal, S., Mani, A., & Mitra, S. (2013). Sex Workers, Stigma and Self-Belief: Evidence from a Psychological Training Program in India. https://www.isid.ac.in/~epu/acegd2014/papers/SanchariRoy.pdf

Government of India. (2011). Census of India. Final Population Tables.

Heintzelman, S. J., & Tay, L. (2017). Subjective well-being: Payoffs of being happy and ways to promote happiness. Positive Psychology Established and Emerging Issues. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315106304

Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. D. (2019). World Happness Report. Oecd, March, 20. https://s3.amazonaws.com/happiness-report/2019/WHR19.pdf

Henly, J. R. (2007). Informal support networks and the maintenance of low-wage jobs. In F. Munger (Ed.), Laboring Below The Line: The New Ethnography of Poverty, Low-Wage Work, and Survival in the Global Economy (pp. 179–203). Russell Sage Foundation. https://www.jstor.org/stable/https://doi.org/10.7758/9781610444163

Himanshu. (2018). Widening gaps, India Inequality Report 2018. https://www.oxfamindia.org/sites/default/files/WideningGaps_IndiaInequalityReport2018.pdf

Howell, R. T., & Howell, C. J. (2008). The relation of economic status to subjective well-being in developing countries: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.536

Isen, A. M. (2000). Positive Affect and Decision Making, Handbook of emotions, M. Lewis & J. Haviland-Jones Ed, 417–435. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1993-98937-013

Kabiru, C. W., Mojola, S. A., Beguy, D., & Okigbo, C. (2013). Growing Up at the “Margins”: Concerns, aspirations, and expectations of young people living in Nairobi’s slums. Journal of Research on Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00797.x

Kearney, M. S., & Levine, P. B. (2020). Role models, mentors, and media Influences. The Future of Children, 30(1), 83–106.

Khaptsova, A., & Schwartz, S. H. (2016). Life satisfaction and value congruence. Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000268

Khilnani, G. C., & Tiwari, P. (2018). Air pollution in India and related adverse respiratory health effects: Past, present, and future directions. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine, 24(2), 108–116. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCP.0000000000000463

Ki, J. B., Faye, S., & Faye, B. (2005). Multidimensional poverty in Senegal: A non-monetary basic needs approach. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3173246

Knight, J., Song, L., & Gunatilaka, R. (2009). Subjective well-being and its determinants in rural China. China Economic Review, 20(4), 635–649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2008.09.003

KoBoToolBox. (2019). KoBoToolbox. https://www.kobotoolbox.org/

Kundu, A. (2003). Urbanisation and urban governance: Search for a perspective beyond neo-liberalism. Economic and Political Weekly, 38(29), 3079–3087.

Lange, M. (2020). Multidimensional poverty in Kolkata’s slums: Towards data driven decision making in a medium-sized NGO. Journal of Poverty and Social Justice. https://doi.org/10.1332/175982720x16034770581665

Leach, C. W., & Smith, H. J. (2006). By whose standard? The affective implications of ethnic minorities’ comparisons to ethnic minority and majority referents. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36(5). https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.315

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131(6), 803.

Maccagnan, A., Wren-Lewis, S., Brown, H., & Taylor, T. (2019). Wellbeing and society: Towards quantification of the co-benefits of wellbeing. Social Indicators Research, 141(1), 217–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1826-7

Mateu, P., Vásquez, E., Zúñiga, J., & Ibáñez, F. (2020). Happiness and poverty in the very poor Peru: measurement improvements and a consistent relationship. Quality & Quantity. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-020-00974-y

Michalos, A. C. (1985). Multiple discrepancies theory (MDT). Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00333288

Moskowitz, J. T., Shmueli-Blumberg, D., Acree, M., & Folkman, S. (2012). Positive affect in the midst of distress: implications for role functioning. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.1133

Mussweiler, T., Gabriel, S., & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2000). Shifting social identities as a strategy for deflecting threatening social comparisons. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.3.398

Myers, D. G., & Diener, E. (1995). Who is happy? Psychological Science, 6(1), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1995.tb00298.x

Nolan, L. B., Bloom, D. E., & Subbaraman, R. (2017). Legal status and deprivation in India’s Urban Slums: An analysis of two decades of national sample survey data. SSRN, 10639. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/161262/1/dp10639.pdf

Ray, B. (2017). Quality of life in selected slums of Kolkata: a step forward in the era of pseudo-urbanisation. Local Environment. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2016.1205571

Reserve Bank of India. (2015). Number and Percentage of Population Below Poverty Line. https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/PublicationsView.aspx?id=16603

Schkade, D. A., & Kahneman, D. (1998). Does living in california make people happy? A Focusing Illusion In Judgments Of Life Satisfaction. Psychological Science, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00066

Sharma, R., Khurana, N., & Bagrij, A. (2019). Satisfaction of life of slum dwellers pre- and post- rehabilitation in India. Scholedge International Journal of Multidisciplinary & Allied Studies https://doi.org/10.19085/journal.sijmas051001

Singh, H. (2016). Increasing rural to urban migration in India: A challenge or an opportunity. International Journal of Applied Research, 2(4), 447–450.

Smyth, J. M., Zawadzki, M. J., Juth, V., & Sciamanna, C. N. (2017). Global life satisfaction predicts ambulatory affect, stress, and cortisol in daily life in working adults. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-016-9790-2

Stewart, E. B., Stewart, E. A., & Simons, R. L. (2007). The effect of neighborhood context on the college aspirations of African American Adolescents. American Educational Research Journal. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831207308637

Strotmann, H., & Volkert, J. (2018). Multidimensional poverty index and happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9807-0

Suldo, S. M., & Huebner, E. S. (2004). Does life satisfaction moderate the effects of stressful life events on psychopathological behavior during adolescence? School Psychology Quarterly, 19(2), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1521/scpq.19.2.93.33313

Sundar, S., Qureshi, A., & Galiatsatos, P. (2016). A Positive Psychology Intervention in a Hindu Community: The Pilot Study of the Hero Lab Curriculum. Journal of Religion and Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0289-5

Tan, J. J. X., Kraus, M. W., Carpenter, N. C., & Adler, N. E. (2020). The association between objective and subjective socioeconomic status and subjective well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000258

Tay, L., Zyphur, M., & Batz, C. L. (2018). Income and subjective well-being: review, synthesis, and future research. Handbook of Well-Being, 1974, 1–12.

The World Bank. (2021). GDP (currentUS$) - India. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=IN

Thoits, P. A. (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510395592

Thorat, A., Vanneman, R., Desai, S., & Dubey, A. (2017). Escaping and falling into poverty in India today. World Development, 93, 413–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.01.004

Tourangeau, R., Rips, L. J., & Rasinski, K. (2000). The psychology of survey response. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511819322

UNDP. (2020). The 2020 Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) | Human Development Reports. Human Development Report. http://hdr.undp.org/en/2020-MPI%0Ahttp://hdr.undp.org/en/2018-MPI%0Ahttp://hdr.undp.org/en/2020-MPI

United Nations. (2015). Sustainable development goals. https://sdgs.un.org/

Vásquez-Vera, H., Palència, L., Magna, I., Mena, C., Neira, J., & Borrell, C. (2017). The threat of home eviction and its effects on health through the equity lens: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.010

Veenhoven, R. (2005). Happiness in hardship. In L. Bruni & P. Porta (Eds.), Economics and happiness (pp. 243–266). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0199286280.003.0011

Veenhoven, R. (2008). Healthy happiness: effects of happiness on physical health and the consequences for preventive health care. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9042-1

Venkata Ratnam, C. S., & Chandra, V. (1996). Sources of diversity and the challenge before human resource management in India. International Journal of Manpower, 17(4–5), 76–108. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437729610127631

Whelan, C. T., Layte, R., & Maître, B. (2004). Understanding the mismatch between income poverty and deprivation: A dynamic comparative analysis. European Sociological Review, 20(4), 287–302. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jch029

Whitaker, K. B., & Moss, D. W. (1976). Titration of human placental alkaline phosphatase with radioactive orthophosphate. Clinica Chimica Acta, 71(2), 277–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-8981(76)90541-6

WHOQoL Group. (1994). The Development of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment Instrument (the WHOQOL). In Quality of Life Assessment: International Perspectives (pp. 41–57). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-79123-9_4

World Bank Group. (2020). Poverty & Equity Brief India. Poverty & Equity Brief India.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr. Jaydeep Chakraborty, Chief Executive Officer at Calcutta Rescue, the Calcutta Rescue Research Collaborative and volunteer researchers Eleo Tibbs (UK), Maurice Lange (UK), and Ezra Spinner (NL) for their contributions to the foundation of this study. Debuprasad Chakraborty & Ananya Chatterjee (CR, India), and the interns (Madhubanti Talukdar, Annesha Dasgupta, Amrita Mukherjee, Sagnik Pramanick, Varbi Mridha) are thanked for all their help with data collection.

Funding

There was no specific funding for this research project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors (ES and JL) contributed equally to the realization of the study and the manuscript i.e., study conception, study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation and writing were performed by both authors. The draft manuscript was critically revised. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. The authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Consent to participate and consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants. The data were anonymized before analysis and publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sulkers, E., Loos, J. Life Satisfaction among the Poorest of the Poor: A Study in Urban Slum Communities in India. Psychol Stud 67, 281–293 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-022-00657-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-022-00657-8