Abstract

Purpose

We report a case in which the use of semaglutide for weight loss was associated with delayed gastric emptying and intraoperative pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents.

Clinical features

A 42-yr-old patient with Barrett’s esophagus underwent repeat upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and ablation of dysplastic mucosa. Two months earlier, the patient had started weekly injections of semaglutide for weight loss. Despite having fasted for 18 hr, and differing from the findings of prior procedures, endoscopy revealed substantial gastric content, which was suctioned before endotracheal intubation. Food remains were removed from the trachea and bronchi using bronchoscopy. The patient was extubated four hours later and remained asymptomatic.

Conclusion

Patients using semaglutide and other glucagon-like peptide 1 agonists for weight management may require specific precautions during induction of anesthesia to prevent pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents.

Résumé

Objectif

Nous rapportons un cas dans lequel l’utilisation de sémaglutide à des fins de perte de poids a été associée à un retard de vidange gastrique et à une aspiration pulmonaire peropératoire du contenu gastrique.

Caractéristiques cliniques

Un patient de 42 ans souffrant d’un œsophage de Barrett a subi une cinquième endoscopie gastro-intestinale supérieure avec ablation de la muqueuse dysplasique. Deux mois plus tôt, le patient avait commencé à recevoir des injections hebdomadaires de sémaglutide pour perdre du poids. Bien qu’à jeun depuis 18 heures et à la différence des évaluations lors des interventions antérieures, l’endoscopie a révélé un contenu gastrique important, qui a été aspiré avant l’intubation endotrachéale. Les restes de nourriture ont été retirés de la trachée et des bronches par bronchoscopie. Le patient a été extubé quatre heures plus tard et est demeuré asymptomatique.

Conclusion

Les patients utilisant du sémaglutide et d’autres agonistes du peptide analog au glucagon-1 pour la gestion du poids pourraient nécessiter des précautions spécifiques lors de l’induction de l’anesthésie pour empêcher l’aspiration pulmonaire du contenu gastrique.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Semaglutide is a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP 1) agonist used for glycemic control in patients with diabetes, which has recently been approved for weight control in certain patients with obesity. We report a case in which the use of semaglutide for weight loss was associated with delayed gastric emptying and intraoperative pulmonary aspiration of gastric content. A written HIPAA release form and written informed consent were obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Case presentation

A 42-yr-old male with gastroesophageal reflux and Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia presented for repeat upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and ablation of dysplastic mucosal areas. This was the fifth procedure in two years, four of which (including the most recent one, three months prior) he had tolerated well under deep sedation with natural airway. One prior procedure was performed under general endotracheal anesthesia. He had a remote history of heavy alcohol use with several complications, including a lung abscess, thought to be the result of aspiration, which was treated conservatively with antibiotics. He had been sober for four years. His other medical history included obesity (body mass index, 37 kg·m−2), obstructive sleep apnea (managed by nightly use of a continuous positive airway pressure machine), and mixed anxiety and depressive disorder. The patient had no history of diabetes. Two months prior to the procedure, he started taking semaglutide for weight loss, at a dose that escalated to weekly 1.7-mg subcutaneous injections. Other daily medications included omeprazole, famotidine, paroxetine, bupropion, and buspirone.

The patient had no gastrointestinal symptoms on the day of the procedure. He was instructed to have nothing by mouth for 8 hr; however, by the time the procedure started, he had been fasting for over 18 hr. An intravenous catheter was inserted, and standard American Society of Anesthesiologists monitoring was used. He was placed in a slight left lateral position, and deep sedation was initiated with a fentanyl bolus, propofol bolus, and propofol infusion. His eyes closed, he became unresponsive to voice and continued to breathe easily, unassisted. Upon introduction of the endoscope, large quantities of liquid and solid material were encountered in the stomach. This was different from all prior procedures, in which the stomach was found to be empty. The gastric content was suctioned through the endoscope, and the patient was intubated rapidly after the administration of additional propofol and succinylcholine. A bronchoscope was inserted through the endotracheal tube and revealed a moderate quantity of liquid and solid material resembling the gastric content, which was suctioned. The procedure was completed, and the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit, sedated, and intubated. He was extubated four hours later, remained asymptomatic, and was discharged home the next day. Four months later, he was doing well.

Discussion

Glucagon-like peptide 1 agonists have been used for glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes1 for over 12 years and have proven to have a very good safety profile. The most prevalent side effects are nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea,1 and are relatively minor. The current recommendations are that GLP 1 agonists may be continued in the perioperative period when used for diabetes.2

In June 2022, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the use of weekly injections of semaglutide for chronic weight management in adults with obesity or overweight and one weight-related condition, such as high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, or high cholesterol.3 The recommended dose is 1.7–2.4 mg once weekly, subcutaneously, which is higher than the dose of 0.25–1 mg used for diabetes management. It is therefore possible that the safety profile may be worse in these conditions. Notably, if we compare two different studies (with different patient populations, admittedly), the prevalence of nausea and vomiting was much higher in patients taking 2.4 mg semaglutide subcutaneously3 than in those taking 0.5 and 1 mg1 (44% vs 2% and 5% for nausea and 31% vs 2% and 3% for vomiting, respectively).

As GLP 1 is an incretin hormone responsible for the regulation of gastric emptying,4 several studies have assessed gastric emptying in patients taking semaglutide using an assay that quantifies paracetamol absorption following a standardized breakfast. Dahl et al.5 showed that in diabetic patients, oral semaglutide decreased acetaminophen absorption in the first hour, but absorption after five hours was unchanged from placebo. In patients with obesity receiving weekly subcutaneous injections, a study found the same pattern as in diabetic patients,6 whereas another study7 found no change in absorption for either the first hour or five hours. Thus, while some controversy exists regarding whether semaglutide may decrease gastric emptying during the first hour, the overall effect appears to be negligible. Nevertheless, the test used has known limitations, and some studies have shown a poor correlation with gastric emptying assessed by scintigraphy.8 Therefore, uncertainty persists. Regarding other GLP 1 agonists, another study found a slowing of gastric emptying in diabetic patients taking liraglutide, using a 13C-octanoic acid breath test, although the extent of the difference and its clinical implications were not addressed.9

In our patient, the start of semaglutide therapy was associated with a clear delay in gastric emptying after 18 hr of fasting, which was not previously observed on several occasions. Although this observation cannot, in itself, unequivocally show that semaglutide causes delayed gastric emptying, it gives, in our view, reason for a significant safety concern, especially since it is consistent with the known mechanism of action of the drug. Other possibilities exist but are less likely. A persistent alcohol-induced gastroparesis four years after quitting is doubtful since previous endoscopies during and immediately after the period of heavy alcohol use revealed an empty stomach. An undisclosed patient non-compliance with the eight hours fasting requirement is also possible, but there is no reason to suspect it, especially for a patient who has always been truthful and consistently showed a genuine concern for his well-being and safety.

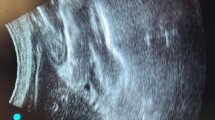

Pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents remains a significant cause of postoperative morbidity and mortality.10 Therefore, preventive adjustments in anesthesia management could be expected to improve overall perioperative outcomes. With a half-life of approximately seven days,11 it will take 23 days (i.e., 3.3 half-lives) for semaglutide levels to drop to less than 10% of the initial blood level, but it is unknown whether holding the drug for this period preoperatively will result in a full recovery of gastric motility. Perhaps the emerging perioperative use of point-of-care ultrasound to assess gastric content12 may provide an answer to this question. As such, until more data become available, a cautious approach would be to consider patients taking semaglutide for weight loss as having a full stomach.

References

Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1834–44. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1607141

Hulst AH, Polderman JA, Siegelaar SE, et al. Preoperative considerations of new long-acting glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in diabetes mellitus. Br J Anaesth 2021; 126: 567–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2020.10.023

Wilding JP, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 989–1002. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2032183

Schirra J, Katschinski M, Weidmann C, et al. Gastric emptying and release of incretin hormones after glucose ingestion in humans. J Clin Invest 1996; 97: 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci118411

Dahl K, Brooks A, Almazedi F, Hoff ST, Boschini C, Baekdal TA. Oral semaglutide improves postprandial glucose and lipid metabolism, and delays gastric emptying, in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2021; 23: 1594–603. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.14373

Hjerpsted JB, Flint A, Brooks A, Axelsen MB, Kvist T, Blundell J. Semaglutide improves postprandial glucose and lipid metabolism, and delays first-hour gastric emptying in subjects with obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab 2018; 20: 610–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.13120

Friedrichsen M, Breitschaft A, Tadayon S, Wizert A, Skovgaard D. The effect of semaglutide 2.4 mg once weekly on energy intake, appetite, control of eating, and gastric emptying in adults with obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab 2021; 23: 754–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.14280

Willems M, Quartero AO, Numans ME. How useful is paracetamol absorption as a marker of gastric emptying? A systematic literature study. Dig Dis Sci 2001; 46: 2256–62. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1011935603893

Meier JJ, Rosenstock J, Hincelin-Méry A, et al. Contrasting effects of lixisenatide and liraglutide on postprandial glycemic control, gastric emptying, and safety parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes on optimized insulin glargine with or without metformin: a randomized, open-label trial. Diabetes Care 2015; 38: 1263–73. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc14-1984

Warner MA, Meyerhoff KL, Warner ME, Posner KL, Stephens L, Domino KB. Pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology 2021; 135: 284–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0000000000003831

Hall S, Isaacs D, Clements JN. Pharmacokinetics and clinical implications of semaglutide: a new glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1 receptor agonist. Clin Pharmacokinet 2018; 57: 1529–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-018-0668-z

El-Boghdadly K, Wojcikiewicz T, Perlas A. Perioperative point-of-care gastric ultrasound. BJA Educ 2019; 19: 219–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2019.03.003

Author contributions

Ion A. Hobai contributed to making the original observation, researching the literature, writing and revising the manuscript. Sandra R. Klein contributed to making the original observation and editing the manuscript.

Disclosures

None.

Funding statement

Departmental only.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Philip M. Jones, Deputy Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Klein, S.R., Hobai, I.A. Semaglutide, delayed gastric emptying, and intraoperative pulmonary aspiration: a case report. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 70, 1394–1396 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-023-02440-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-023-02440-3