Abstract

Purpose

During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, restricted visitation policies were enacted at acute care facilities to reduce the spread of COVID-19 and conserve personal protective equipment. In this study, we aimed to describe the impact of restricted visitation policies on critically ill patients, families, critical care clinicians, and decision-makers; highlight the challenges faced in translating these policies into practice; and delineate strategies to mitigate their effects.

Method

A qualitative description design was used. We conducted semistructured interviews with critically ill adult patients and their family members, critical care clinicians, and decision-makers (i.e., policy makers or enforcers) affected by restricted visitation policies. We transcribed semistructured interviews verbatim and analyzed the transcripts using inductive thematic analysis.

Results

Three patients, eight family members, 30 clinicians (13 physicians, 17 nurses from 23 Canadian intensive care units [ICUs]), and three decision-makers participated in interviews. Thematic analysis was used to identify five themes: 1) acceptance of restricted visitation (e.g., accepting with concerns); 2) impact of restricted visitation (e.g., ethical challenges, moral distress, patients dying alone, intensified workload); 3) trust in the healthcare system during the pandemic (e.g., mistrust of clinical team); 4) modes of communication (e.g., communication using virtual platforms); and 5) impact of policy implementation on clinical practice (e.g., frequent changes and inconsistent implementation).

Conclusions

Restricted visitation policies across ICUs during the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected critically ill patients and their families, critical care clinicians, and decision-makers.

Résumé

Objectif

Au cours de la première vague de la pandémie de COVID-19, des politiques de visite restreintes ont été adoptées dans les établissements de soins aigus afin de réduire la propagation de la COVID-19 et d’économiser les équipements de protection individuelle. Dans cette étude, nous avons cherché à décrire l’impact des politiques de visite restreintes sur les patients gravement malades, les familles, les intensivistes et les décideurs, ainsi qu’à souligner les difficultés rencontrées dans la mise en pratique de ces politiques et à définir des stratégies pour en atténuer les effets.

Méthode

Une méthodologie de description qualitative a été utilisée. Nous avons mené des entretiens semi-structurés avec des patients adultes gravement malades et les membres de leur famille, les intensivistes et les décideurs (c.-à-d. les stratèges ou les responsables de l’application de la loi) touchés par les politiques de visite restreintes. Nous avons transcrit textuellement les entretiens semi-structurés et analysé les transcriptions à l’aide d’une analyse thématique inductive.

Résultats

Trois patients, huit membres de leur famille, 30 cliniciens (13 médecins, 17 infirmières de 23 unités de soins intensifs canadiennes) et trois décideurs ont participé à ces entrevues. L’analyse thématique a été utilisée pour identifier cinq thèmes : 1) l’acceptation des visites restreintes (p. ex., accepter avec des préoccupations); 2) l’impact des visites restreintes (p. ex., défis éthiques, détresse morale, patients mourant seuls, charge de travail accrue); 3) la confiance dans le système de santé pendant la pandémie (p. ex., méfiance à l’égard de l’équipe clinique); 4) les modes de communication (p. ex., communication à l’aide de plateformes virtuelles); et 5) l’incidence de la mise en œuvre des politiques sur la pratique clinique (p. ex., changements fréquents et mise en œuvre incohérente).

Conclusion

Les politiques de visite restreintes dans les unités de soins intensifs pendant la pandémie de COVID-19 ont eu un impact négatif sur les patients gravement malades et leurs familles, les intensivistes et les décideurs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, flexible family visitation policies were increasingly adopted in most hospitals.1,2,3,4,5,6 In the intensive care unit (ICU), such policies are associated with reduced incidence of delirium, reduced anxiety among critically ill patients and their family members, and increased patient and family satisfaction.6,7,8,9,10 The first hospital visitation restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic were enacted as part of public health measures aimed to reduce the spread of COVID-19 and preserve limited quantities of personal protective equipment (PPE).11 Most policies allowed no visitors with specific exemptions (e.g., end-of-life).

Implementation of restricted visitation policies, although crucial in a pandemic, has been criticized for insufficient input from patients, families, and critical care clinicians.12 The impacts in ICU settings have not been well documented, and research on clinician experiences is still emerging.13 In this qualitative interview study, we aimed to describe the impact of restricted visitation policies during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic across Canada on critically ill adults, their families, clinicians, and decision-makers who developed or enforced the policies.

Materials and methods

Study design

We employed a qualitative description design as this inquiry sought a naturalistic methodological approach that was informed by a constructivist perspective.14 We chose not to conduct a mixed-methods study given this was an exploratory study that aimed to describe restricted visitation during the COVID-19 pandemic. We expected that our study would provide foundational knowledge to inform a future in-depth mixed-methods study. We reported this study in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist (Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] eTable 1).15 We conducted interviews from 17 July to 8 October 2020, during the first and second SARS-CoV-2 infection waves in Canada. During this period, some hospitals still had no-visitor policies, either outright or with exceptions, while some visitation restrictions were starting to loosen, allowing all patients to have a designated visitor.16 The University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board approved this study (Calgary, AB, Canada; Ethics ID, REB20-0944).

Participants

We recruited patients and family representatives (who were in the ICU during the COVID-19 pandemic) through our research network Twitter account (@C3ResNetwork), which has an extensive following from patient-centered organizations and critical care colleagues and societies (ESM eAppendix 1). We also recruited from a related national study whereby participants agreed to be contacted for future COVID-19 research opportunities.17 We purposively recruited critical care clinicians (i.e., physicians, registered nurses, and registered respiratory therapists) through emails to professional societies (Canadian Critical Care Society, Canadian Association of Critical Care Nurses, and Canadian Society of Respiratory Therapists) and through social media, to get representation from all provinces. Decision-makers, defined as persons who developed and/or enforced a policy, were contacted directly. Eligibility criteria included English/French-speaking adults (≥ 18 yr) who were able to provide informed consent.

Interview guide

The interview guide was developed by the research team (MA- [S. M.] and PhD- [J. P. L.] level qualitative researchers and researchers with qualitative experience [K. F., K. K.]), based on team members’ (i.e., patient partners, nurses, physicians) and the larger Canadian critical care community’s clinical experiences (e.g., moral distress, changes to communication) and relevant publications.13,18,19,20,21,22 The interview guide had open-ended questions (to allow participants to share individual perspectives and experiences) and was flexible to allow the interviewer to probe and ask unplanned questions to encourage participants to provide more detail. The interview guide was piloted with three participants (one family member, physician, and nurse) and refined prior to administration (ESM eAppendices 2–4).

Data collection

Researchers trained in qualitative methods conducted all interviews (nurse with qualitative experience [K. S.]). All researchers kept a reflexive journal for critical self-reflection on the impact their background/experience had on the research process.23 Prior to each interview, participants were sent an e-mail with information about the interview and a consent form. Each participant’s informed verbal consent was obtained prior to the interview. We conducted all interviews per participant preference (e.g., phone, virtual platforms). Family and patient interviews were ~60 min long, and clinician and decision-maker interviews were 30–45 min long. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, reviewed for accuracy, redacted for identifying information, and imported into NVivo-12 (QSR International, Melbourne, Vic, Australia) for data management and analysis. All participants were sent a personalized summary of their interview for member checking and were able to respond and request changes (e.g., redacting details of experience shared to ensure privacy of involved parties).24

Data analysis

Inductive thematic analysis was conducted as described by Braun and Clarke.25 Four researchers (K. K., N. J. [intensivist with qualitative experience], K. S., and S. M.) analyzed the interview transcripts independently and in duplicate, concurrently with data collection. Transcripts were analyzed as four separate groups: patient/family member (combined due to the small number of patient participants and overlap in experiences/emotions), physician, nurse, or decision-maker transcripts. Researchers listened to a recording of each interview and themes were developed and coded based on what participants described as most important/impactful when responding to the questions and probes. A codebook was created for each participant group and we identified shared features and experiences across participants. The research team met weekly with the principal investigators (K. F., J. P. L.) to iteratively read, review, and refine the themes and subthemes based on new insights that emerged as the study progressed. We conducted and iteratively analyzed interviews and invited participants for interviews until no new patterns or themes were identified and it was determined by the research team that thematic saturation had been reached. The same four researchers then applied codes from the finalized codebook systematically to all 44 transcripts and critically compared results to ensure continued agreement and that the data remained true to participants’ subjective accounts, rather than to researchers’ interpretations, consistent with the constructivist perspective underlying the research.

Results

Participants

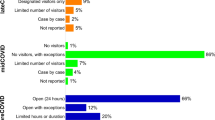

Three patients, eight family members (four children, three spouses, one sibling), 30 clinicians (13 attending physicians, 15 bedside nurses, one clinical nurse specialist, one clinical nurse educator), and three decision-makers participated (Table 1). Clinicians were from 23 ICUs in eight provinces, which included ICUs from high-volume wave 1 ICUs in Ontario and Quebec (a peak of 264 COVID-19 patients admitted to Ontario, 258 to Quebec) and low-volume wave 1 ICUs in other provinces (peak of 22 patients admitted to Alberta).26 Most clinicians practiced in academic institutions (22/30; 73%, regional: 6/30; 20%, urban/nonacademic: 2/30; 7%). Most participants reported that their ICU visitation policy was no visitors (22/44; 50%), no visitors with exceptions (e.g., end-of-life, 15/44; 34%), or one designated visitor (7/44; 16%).

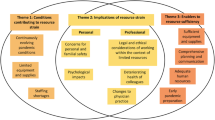

Thematic analysis

Thematic analysis identified five major themes that reached saturation and were shared across all participant groups: 1) acceptance of restricted visitation; 2) impact of restricted visitation; 3) trust in the healthcare system during the pandemic; 4) modes of communication; and 5) impact of policy implementation on clinical practice. An overview of themes/subthemes is presented in Table 2, with exemplar quotations from each stakeholder group included in ESM eTable 2.

Acceptance of restricted visitation

Overall, patients and family members shared that they understood that visitor restrictions were important to prevent the spread of COVID-19 (quotation 1 [Q1]), and that the ICU care team was “doing the best they could.” Although clinicians were accepting of the circumstances, most felt the restricted visitation was too restrictive. Most clinicians also thought that policies were not appropriate because they did not match what was going on in their city (Q2) or that family should always be allowed in the ICU because they are an important part of patient care (Q3). Clinicians were split on whether it was appropriate to allow visiting for patients with COVID-19. Some expressed concerns that visitors may also be infected with SARS-CoV-2 and expose clinicians. Conversely, others believed that COVID-19 patients could have visitors if the family were provided with appropriate PPE or could visit through an exterior window (Q4).

Impact of restricted visitation

Patients/family members, clinicians, and decision-makers described how restricted visitation impacted them personally. This included threats to their psychosocial well-being. Family members often used the words anxious (Q5) and guilt (Q6) when describing how it felt to not visit their loved one in the ICU. Clinicians often used the terms distress (Q7) and sad (Q8) when describing how they felt when family could not visit. Clinicians also shared how difficult it was to predict end-of-life and the interpretation of policies in these circumstances (i.e., visitation policies were frequently reported to be different during end-of-life). Several clinicians shared experiences of family members not arriving in time before their loved one died. A few clinicians were distressed in situations when an older adult was in the ICU, but their partner was isolated at home without someone to check in on them. When participants were asked about the impacts of restricted visitation, all participant groups shared how the lack of family presence impacted patient care. Families and patients shared how families were not there to act as an advocate for the patient (Q9) or provide the patient with support and encouragement (Q10). Clinicians felt it was detrimental when family was not present to help with patient care (e.g., eating, physiotherapy, or orientation) (Q11) or provide clinicians with information about the patient (Q12). Many clinicians described how restricted visitation policies negatively impacted their relationships with the family. This included conflicts with families when enforcing the policy (Q13) or not answering calls from family members who were not the designated contact person. Clinicians also felt they could not develop a connection with a family when they were not at the bedside. When clinicians were asked how restricted visitation policies affected their workflow, they were divided regarding whether restricted visitation increased (e.g., frequency and length of phone calls, coordinating virtual visits, teaching/monitoring visitors) or decreased (e.g., rounds more efficient, fewer consultants coming to the ICU, fewer informal conversations with family members) their workload.

Trust in the healthcare system during the pandemic

All participants described experiences related to trust in the healthcare system during the pandemic. Family members did not have assurance that their loved one did not die alone (Q14). Similarly, clinicians described how transparency was challenging when family members could not see the clinical condition of their loved one or what care was being provided (Q15). Some clinicians mistrusted senior management when a policy was not applied consistently and family was allowed to visit when the physician or nurse told them they could not (Q16) or when colleagues found ways around the policy (Q17). In addition, clinicians experienced mistrust when family members found ways around the policy (e.g., sneaking in to visit, switching family members when only one consistent visitor was allowed). Family members admitted to finding ways around the policy to visit their loved ones.

Modes of communication

When participants were asked to describe how they communicated during restricted visitation, most said that discussions between clinicians and family members occurred via telephone. Most participants reported that virtual visits occurred between patients and family members (Q18), though physicians sometimes used virtual platforms so that they could see the family members when breaking bad news or having sensitive conversations about prognosis or goals of care (Q19). Though several participants stated that virtual visitation was a good way for family to visit with the patient, see the patient’s room and the clinical condition of the patient, one nurse noted that family members may have found this distressing (Q20). No family members in the current study identified seeing their loved one by virtual platform as distressing.

All participant groups described the personal challenges faced with these modes of communication. Family members and clinicians noted that in some cases (e.g., due to socioeconomic status), communication devices were not available to patients or families (i.e., patients or family members who did not have devices for virtual visits or could not afford the long-distance charges), language barriers, lacked familiarity with technology, or the patient’s clinical condition (i.e., unable to interact, too weak to hold phone). Decision-makers and clinicians also identified several operational challenges, which included coordinating multiple family members/clinicians, infection control/prevention measures, and training staff (e.g., using iPads for virtual meetings).

Impact of policy implementation on clinical practice

Clinicians described how restricted visitations policies impacted their practice. This included organizational factors, where clinicians took on additional tasks such as enforcing the visitation policy and, in some cases, accompanying families to the patient room or supervising their donning and doffing of PPE (Q21). Physicians described how restricted visitation policies forced them to change their communication structure, which included the shift of goals of care discussions to the phone rather than face-to-face (Q22), and the casual updates when family were present at the bedside were replaced with more frequent phone calls. Families also described challenges associated with this change in communicating with the clinical team during rounds or finding a time with busy bedside nurses to receive an update.

Clinicians and decision-makers also described policy-specific challenges. This included frequent visitation policy changes that were often communicated on a Friday afternoon when there was no one available to answer questions, causing confusion with staff, which resulted in inconsistent application of the policy (e.g., breach of policy, exceptions, varied interpretations). Policy changes were also communicated via innumerable emails, which clinicians reported made them difficult to keep up with. Lastly, clinicians noted that policy changes revealed ethical challenges such as equity, confidentiality, privacy, and the need to avoid biased decisions in constructing policies.

Strategies to improve restricted visitation policies

The most common strategies suggested by participants to improve visitation policies are included in Table 3. Most strategies recommended increased organizational support. Most family members and clinicians found it difficult to keep up with the rapidly changing policies and suggested ways to mitigate this. This included a centralized place for the most recent policy (e.g., website) or patient navigators who communicate the policy with visitors. Another commonly suggested strategy was to allow visits for all ICU patients given the risk of sudden death.

Discussion

In this qualitative interview-based study, we describe the impressions and perceived impact of restricted visitation policies during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on critically ill adults, their families, clinicians caring for them, and decision-makers. Most hospitals did not allow visitors, or only with special exceptions. Our findings suggest that restricted visitation policies had negative impacts on all stakeholders (e.g., ethical challenges, moral distress, patients dying alone, intensified workload), and that an ICU-specific policy, additional organizational support, improved communication of policy changes, and engagement of relevant stakeholders in future policy decisions are important strategies to mitigate these impacts.

Several editorials,27,28,29,30 news stories,20,22,31,32 and studies have shared the personal impact that restricted visitation policies during the COVID-19 pandemic had on patients, family members,33,34 and clinicians. Family members of critically ill patients found policies restrictive but understood their purpose to reduce the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Clinicians questioned the appropriateness of the policies and often experienced distress when family members were not allowed to visit their loved ones, especially in end-of-life situations.28,35 This included the perception of clinicians that they were responsible for keeping family from seeing their loved one, including at the end-of-life. It is challenging for clinicians to predict end-of-life given the occasional unpredictability of critical illness; this study highlights the difficulty of merging and implementing policies in the setting of unforeseeable clinical circumstances.36,37,38 Many participants suggested that ICUs should always have visitor exceptions, which are supported by a recent article.39 This may be feasible in ICUs that have single patient rooms or require passes where the ICU can control visitor entry. The rooming of multiple patients into single rooms to accommodate increased patient volumes complicates visits. Furthermore, it is unclear how to manage visits when a patient is allowed visitors in the ICU but not after transfer to a hospital ward.

Given that infectious disease outbreaks are inevitable, our results provide several strategies that could mitigate the effects of restricted visitation. This includes having an ICU-specific policy that is consistently applied among healthcare professionals and administrators. Also, we need to decide how safe visits can be accomplished with appropriate PPE (and stakeholder training),39 regulating the number of visitors (except in end-of-life situations), staggering visits (e.g., odd room numbers then even room numbers), or offering limited visit time (e.g., duration or limited visiting hours).39 This requires organizational support, which could include a central location to post updated policies, communication of policies within healthcare settings at the beginning of the week (i.e., avoiding Friday afternoon policy changes), additional guidance for executing mixed media communication (e.g., privacy considerations),40 and possibly patient navigators who can communicate policies and educate visitors on appropriate PPE donning and doffing.41 Lastly, it is important that policy decisions are made with the ongoing input of stakeholders.5

The strengths of this study include that interview guides were codesigned by patient partners, clinicians, and researchers, and tested in pilot interviews before use. The study population included patients, families, clinicians, and decision-makers from multiple sites (academic/nonacademic) across Canada. This study also has several limitations. First, given the regional differences in how each province was affected and responded to the first wave of the pandemic, it is possible that thematic saturation was not reached on some region-specific subthemes in our data. Moreover, the current study was not designed to understand if the perspectives of respondents differed substantially because of a center’s relative proportion of admitted COVID-19 patients. Nevertheless, we included unique viewpoints to ensure that a breadth of views and experiences were represented. Second, it is possible that some perspectives were missed, given that stakeholders may have been motivated to participate based on their experience with restricted visitation policies. For example, the actual number of patients and family members who participated was lower than that of healthcare professionals and may limit our ability to speak on some of the nuances in the identified subthemes. Nevertheless, thematic saturation was reached for the major themes for all participant groups. While we recruited to achieve geographic representation from across the provinces, we did not purposively sample to ensure representation of sex, gender, age, and ethnicity. The lack of purposive sampling was not because we did not see the value in including diversity, but that we cast our net wide using social media (seen as an appropriate tool when recruiting hard-to-reach populations)42,43 and interviewed everyone who expressed interest. Third, though the current study was conducted during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, we did not have an idea whether the units were at the peak or the nadir at the actual time of the interview. Moreover, the study occurred before the SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern emerged and the availability of vaccines, both which may have biased participants to favor more strict and less strict policies, respectively.

Conclusions

During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, health authorities and hospitals moved quickly to restrict visits to hospitals to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2. These policies negatively impacted critically ill adults and their families, clinicians, and decision-makers. When developing and implementing restricted visitation policies, policy makers should balance mitigation of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in a hospital environment and the potential negative impact of restricted visitation policies on patients, families, and clinicians. When possible, patients, family members, clinicians, and decision-makers should be engaged in developing visitation policies to help achieve this equilibrium. Peer-reviewed literature should also be consulted, which may be pivotal for decision-making should similar circumstances arise in future. Now is an important time to do this work to ensure that engagement is in place for future communicable disease outbreaks.

References

Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, et al. Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med 2017; 45: 103–28. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002169

Ning J, Slatyer S. When 'open visitation in intensive care units' meets the COVID-19 pandemic. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2021: 62: 102969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102969

Milner KA, Goncalves S, Marmo S, Cosme S. Is open visitation really "open" in adult intensive care units in the United States? Am J Crit Care 2020; 29: 221–5. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2020331

Milner KA, Marmo S, Goncalves S. Implementation and sustainment strategies for open visitation in the intensive care unit: a multicentre qualitative study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2021: 62: 102927. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102927

Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement (CFHI). Re-integration of family caregivers as essential partners in care in a time of COVID-19. Available from URL: https://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/docs/default-source/itr/tools-and-resources/bt-re-integration-of-family-caregivers-as-essential-partners-COVID-19-e.pdf?sfvrsn=5b3d8f3d_2 (accessed April 2022).

Rosa RG, Tonietto TF, da Silva DB, et al. Effectiveness and safety of an extended ICU visitation model for delirium prevention: a before and after study. Crit Care Med 2017; 45: 1660–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002588

Nassar Junior AP, Besen BA, Robinson CC, Falavigna M, Teixeira C, Rosa RG. Flexible versus restrictive visiting policies in ICUs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2018; 46: 1175–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000003155

Fumagalli S, Boncinelli L, Lo Nostro A, et al. Reduced cardiocirculatory complications with unrestrictive visiting policy in an intensive care unit: results from a pilot, randomized trial. Circulation 2006; 113: 946–52. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.572537

Westphal GA, Moerschberger MS, Vollmann DD, et al. Effect of a 24-h extended visiting policy on delirium in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 2018; 44: 968–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-018-5153-5

Novaes MA, Knobel E, Karam CH, Andreoli PB, Laselva C. A simple intervention to improve satisfaction in patients and relatives. Intensive Care Med 2001; 27: 937. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001340100910

Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). From risk to resilience: an equity approach to COVID-19. Available from URL: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/from-risk-resilience-equity-approach-covid-19.html (accessed April 2022).

Andrist E, Clarke RG, Harding M. Paved with good intentions: hospital visitation restrictions in the age of Coronavirus disease 2019. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2020; 21: e924–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000002506

Cook DJ, Takaoka A, Hoad N, et al. Clinician perspectives on caring for dying patients during the pandemic: a mixed-methods study. Ann Intern Med 2021; 174: 493–500. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-6943

Bradshaw C, Atkinson S, Doody O. Employing a qualitative description approach in health care research. Glob Qual Nurs Res 2017; 4. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393617742282

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 19: 349–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Fiest KM, Krewulak KD, Hiploylee C, et al. An environmental scan of visitation policies in Canadian intensive care units during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Can J Anesth 2021; 68: 1474–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-021-02049-4

Leigh JP, Fiest K, Brundin-Mather R, et al. A national cross-sectional survey of public perceptions of the COVID-19 pandemic: self-reported beliefs, knowledge, and behaviors. PLoS One 2020; 15: e0241259. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241259

Haines A. Family of woman who died from COVID-19 calls for uniform policy on hospital visitations. Available from URL: https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/family-of-woman-who-died-from-covid-19-calls-for-uniform-policy-on-hospital-visitations-1.4884913 (accessed April 2022).

Bridges A. Am I going to see anyone again?': hospital patients isolated from loved ones as COVID-19 stops family visits. Available from URL: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatoon/covid-19-family-members-hospital-visitation-1.5514086 (accessed April 2022).

Stillger N. Edmonton family reacts to Alberta hospital visit ban amid COVID-19 pandemic: "It's heartbreaking". Available from URL: https://globalnews.ca/news/6781893/edmonton-family-alberta-hospital-visit-ban-covid-19/ (accessed April 2022).

The Lancet. Palliative care and the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020; 395: 1168. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30822-9

Bunkall A. Coronavirus: Doctor ‘has nightmares’ as his patients die alone. Available from URL: https://news.sky.com/story/coronavirus-doctors-heartbreak-at-seeing-covid-19-patients-die-alone-11972105 (accessed April 2022).

Ortlipp M. Keeping and using reflective journals in the qualitative research process. Qual Rep 2008; 13: 695–705. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2008.1579

Birt L, Scott S, Cavers D, Campbell C, Walter F. Member checking: a tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qual Health Res 2016; 26: 1802–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316654870

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bagshaw SM, Zuege DJ, Stelfox HT, et al. Association between pandemic Coronavirus disease 2019 public health measures and reduction in critical care utilization across ICUs in Alberta, Canada. Crit Care Med 2022; 50: 353–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000005275

Rose L, Cook A, Casey J, Meyer J. Restricted family visiting in intensive care during COVID-19. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2020; 60: 102896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102896

Wakam GK, Montgomery JR, Biesterveld BE, Brown CS. Not dying alone—modern compassionate care in the COVID-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: e88. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2007781

Montauk TR, Kuhl EA. COVID-related family separation and trauma in the intensive care unit. Psychol Trauma 2020; 12: S96–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000839

Munshi L, Evans G, Razak F. The case for relaxing no-visitor policies in hospitals during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. CMAJ 2020; 193: E135–7. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.202636

Holliday I. B.C. family frustrated by hospital's enforcement of COVID-19 essential visitors policy. Available from URL: https://vancouverisland.ctvnews.ca/b-c-family-frustrated-by-hospital-s-enforcement-of-covid-19-essential-visitors-policy-1.4980772 (accessed April 2022).

Kanaris C. Moral distress in the intensive care unit during the pandemic: the burden of dying alone. Intensive Care Med 2020; 47: 141–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06194-0

Kentish-Barnes N, Cohen-Solal Z, Morin L, Souppart V, Pochard F, Azoulay E. Lived experiences of family members of patients with severe COVID-19 who died in intensive care units in France. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4: e2113355. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13355

Feder S, Smith D, Griffin H, et al. "Why couldn't I go in to see him?" Bereaved families' perceptions of end-of-life communication during COVID-19. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021; 69: 587–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16993

Downar J, Kekewich M. Improving family access to dying patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9: 335–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00025-4

Luce JM. End-of-life decision making in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 182: 6–11. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201001-0071CI

Fischer SM, Gozansky WS, Sauaia A, Min SJ, Kutner JS, Kramer A. A practical tool to identify patients who may benefit from a palliative approach: the caring criteria. J Pain Symptom Manage 2006; 31: 285–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.08.012

Frick S, Uehlinger DE, Zuercher Zenklusen RM. Medical futility: predicting outcome of intensive care unit patients by nurses and doctors--a prospective comparative study. Crit Care Med 2003; 31: 456–61. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000049945.69373.7C

Mistraletti G, Giannini A, Gristina G, et al. Why and how to open intensive care units to family visits during the pandemic. Critical Care 2021; 25: 191. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-021-03608-3

Nittari G, Khuman R, Baldoni S, et al. Telemedicine practice: review of the current ethical and legal challenges. Telemed J E Health 2020; 26: 1427–37. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2019.0158

Rose L, Yu L, Casey J, et al. Communication and virtual visiting for families of patients in intensive care during COVID-19: a UK national survey. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2021; 18: 1685–92. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.202012-1500OC

Burke-Garcia A, Mathew S. Leveraging social and digital media for participant recruitment: a review of methods from the Bayley short form formative study. J Clin Transl Sci 2017; 1: 205–7. https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2017.9

Straubhaar R. The methodological benefits of social media: “studying up” in Brazil in the Facebook age. Int J Qual Stud Educ 2015; 28: 1081–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2015.1074750

Author contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to this work. Kirsten M. Fiest, Karla D. Krewulak, Henry T. Stelfox, and Jeanna P. Leigh designed the study and facilitated acquisition of the data and interpreted the data. All authors provided expert consultation. Kirsten M. Fiest, Karla D. Krewulak, and Natalia Jaworska drafted the manuscript, and all authors critically revised successive versions of the manuscript and approved the final version for submission. Kirsten M. Fiest has full access to all the study data and assumes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Janet Wong, Kara Plotnikoff, and Laura Hernández for assisting with participant interviews. This manuscript underwent an internal peer review process with the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group, and we thank the helpful contributions made by Dr. Karen Choong and Dr. Shannon Fernando.

Disclosures

This study is not registered in a public registry of clinical trials.

Funding statement

Dr. Bagshaw is supported by a Canada Research Chair in Critical Care Medicine. Dr. Burns holds a Physician Services Incorporated Mid-Career Research Award. Dr. Cook is supported by a Canada Research Chair in Critical Care Medicine. Dr. Fowler is the H. Barrie Fairley Professor of Critical Care Medicine of the University Health Network and the University of Toronto Interdepartmental Division of Critical Care Medicine. Dr. Patten is supported by the Cuthbertson and Fischer Chair in Pediatric Mental Health at the University of Calgary. All other authors declare no support from any organization for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. This study was supported by a COVID-19 Rapid Response Funding Grant to Dr. Kirsten M. Fiest from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Stephan K. W. Schwarz, Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fiest, K.M., Krewulak, K.D., Jaworska, N. et al. Impact of restricted visitation policies during COVID-19 on critically ill adults, their families, critical care clinicians, and decision-makers: a qualitative interview study. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 69, 1248–1259 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-022-02301-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-022-02301-5