Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the perceptions and practices of Canadian cardiovascular anesthesiologists and intensivists towards intravenous albumin as a resuscitation fluid in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of cardiac anesthesiologists and intensivists involved in the care of cardiac surgical patients. The 22-item survey included seven open-ended questions and assessed practice patterns and attitudes towards albumin. Descriptive statistics were analyzed using counts and proportions. Qualitative data were analyzed to identify themes describing albumin use patterns in Canada.

Results

A total of 133 respondents from seven provinces participated, with 83 (62%) using albumin perioperatively. The majority of respondents (77%) felt a low fluid balance in cardiac surgical patients was important, and that supplementing crystalloids with albumin was helpful for this objective (67%). There was poor agreement among survey respondents regarding the role of albumin for faster vasopressor weaning or intensive care discharge, and ≥ 90% did not feel albumin reduced mortality, renal injury, or coagulopathy. Nevertheless, cardiac surgical patients were identified as a distinct population where albumin may help to minimize fluid balance. There was an acknowledged paucity of formal evidence supporting possible benefits. Fewer than 10% of respondents could identify institutional or national guidelines for albumin use. A lack of evidence supporting albumin use in cardiac surgical patients, especially those at highest risk of complications, was a frequently identified concern.

Conclusions

The majority of Canadian anesthesiologists and intensivists (62%) use albumin in cardiac surgical patients. There is clinical equipoise regarding its utility, and an acknowledged need for higher quality evidence to guide practice.

Résumé

Objectif

Évaluer les perceptions et les pratiques des anesthésiologistes et intensivistes cardiovasculaires canadiens à l’égard de l’albumine intraveineuse comme liquide de réanimation pour les patients bénéficiant d’une chirurgie cardiaque.

Méthode

Nous avons mené un sondage transversal auprès d’anesthésiologistes et d’intensivistes cardiaques impliqués dans les soins aux patients de chirurgie cardiaque. Le sondage en 22 éléments comprenait sept questions ouvertes et évaluait les habitudes de pratique et les attitudes des praticiens à l’égard de l’albumine. Les statistiques descriptives ont été analysées à l’aide de dénombrements et de proportions. Des données qualitatives ont été analysées pour identifier des thèmes décrivant les tendances d’utilisation de l’albumine au Canada.

Résultats

Au total, 133 répondants de sept provinces ont participé, et 83 (62 %) utilisent l’albumine en périopératoire. La majorité des répondants (77 %) estimaient qu’un bilan liquidien négatif était important chez les patients en chirurgie cardiaque et que la supplémentation en cristalloïdes par de l’albumine était utile pour atteindre cet objectif (67 %). Il y avait un faible accord parmi les répondants concernant le rôle de l’albumine pour accélérer le sevrage des vasopresseurs ou la sortie de soins intensifs, et ≥ 90 % ne pensaient pas que l’albumine réduisait la mortalité, les lésions rénales ou la coagulopathie. Néanmoins, les patients en chirurgie cardiaque ont été identifiés comme une population distincte pour laquelle l’albumine pourrait contribuer à minimiser le bilan liquidien. Il y avait un manque reconnu de données probantes formelles à l’appui des avantages possibles. Moins de 10 % des répondants ont pu trouver des lignes directrices institutionnelles ou nationales portant sur l’utilisation de l’albumine. Le manque de données probantes à l’appui de l’utilisation de l’albumine chez les patients en chirurgie cardiaque, en particulier chez ceux présentant le risque le plus élevé de complications, était une préoccupation fréquemment identifiée.

Conclusion

La majorité des anesthésiologistes et intensivistes canadiens (62 %) utilisent l’albumine chez les patients en chirurgie cardiaque. Il existe un équilibre clinique quant à son utilité et un besoin reconnu de données probantes de meilleure qualité pour guider la pratique.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Intravenous fluids are ubiquitously used in the perioperative management of cardiac surgical patients. There are two types of fluids—crystalloids and colloids—and there has been a long-standing, multidecade debate in medicine, surgery, and intensive care about the value, safety, and benefit of colloids versus crystalloid use for fluid replacement.1,2 Crystalloids are electrolyte solutions that are manufactured in a variety of different compositions. Advantages of crystalloids include their low cost, widespread availability, and long history of clinical familiarity.3 Nevertheless, because they do not exert colloid oncotic pressure, crystalloids may not be as effective for intravascular volume expansion, which may contribute to interstitial fluid overload and worse patient outcomes.3 Conversely, colloid solutions contain larger molecules of either synthetic (e.g., starches) or human-derived (e.g., albumin) origin, which exert an oncotic pressure that may better facilitate intravascular volume retention and sustained resuscitation. Nevertheless, colloids are 20-100 times more expensive than crystalloids. The literature supporting the efficacy and safety of colloids over crystalloids is mixed, and there are no international guidelines or updated systematic reviews addressing this.2,4

In Canada, there are safety concerns related to hydroxyethyl starches that have limited the availability of synthetic colloids,5 rendering albumin, a blood product purified from pooled human plasma, the most widely available colloid.5,6 Albumin is distributed by the Canadian Blood Services (CBS) and Héma-Québec. However, CBS does not currently include cardiac surgery as a recognized indication for albumin use because of the lack of high-quality evidence showing benefit over crystalloids.6,7 Nevertheless, albumin remains available for use by clinicians at their discretion for this indication and is frequently administered in the routine perioperative care of cardiac surgical patients, either as part of the pump prime or for volume resuscitation.5,6

Few studies have investigated current practices and conditions for perioperative albumin use in Canada; however, preliminary data suggest substantial variability exists across Canadian institutions and individual providers. A post hoc analysis from a national multicentre perioperative cardiac surgery trial revealed that albumin use by site ranged from 4.8% to 97.4% in patients with excessive bleeding after cardiac surgery but that overall, more than 70% of all included cardiac surgical patients received one or more vials of albumin during their admission.8 Recent practice surveys from the USA and Europe also show that albumin use in cardiac surgical patients remains highly variable. In a European survey of cardiac anesthesiologists, only 11% of respondents said they would consider using albumin in the operating room,9 whereas in the USA 37% of anesthesiologists and 39% of surgeons considered albumin their first choice fluid for intravascular volume replacement in nonbleeding patients.9,10 These studies support a clear lack of clinical consensus regarding the indications for albumin administration in cardiac surgery.

Given this lack of consensus and apparent variability in albumin administration to cardiac surgical patients, we sought to understand the attitudes of Canadian cardiac anesthesiologists and cardiovascular intensivists towards albumin use. We therefore conducted an anonymous cross-sectional survey to evaluate the perceptions and current practices of Canadian cardiac anesthesiologists and cardiovascular intensivists with respect to perioperative albumin administration in cardiac surgical patients. This information may assist in the development and implementation of evidence-based transfusion guidelines and in identification of controversial areas of clinical practice needing support from high-quality evidence.

Methods

Study population

Cardiac anesthesiologists and intensivists specializing in adult cardiovascular critical care at Canadian academic or academic-affiliated institutions were eligible for inclusion in this study.

Recruitment and sampling

The study team identified a cardiac anesthesiology or cardiovascular intensive care unit (ICU) clinician at 25 different institutions, often with the assistance of the local departmental chair, to serve as a key contact person. This person was asked to identify individuals at their institution who fit the inclusion criteria for the study and distribute a recruitment email on behalf of the study team. The recruitment email provided basic information about the study (e.g., study purpose, time commitment, anonymity, and protection of information collected) and a link to the online survey. An email reminder to complete the survey was sent approximately 14 days following the initial recruitment email. This process was informed by the Dillman Tailored Design Method, which is commonly used to maximize survey response rates.11 Nonbinding incentives, such as a charity donation offered for each participant response collected, were used. Consent was inferred from participation in the online survey, which was clearly stated in the recruitment and reminder emails. Respondents were further encouraged to forward the survey link to peers meeting the study inclusion criteria. This additional peer recruitment process was used to reduce the potential biases from the initial convenience sample of participants.12 The study protocol was approved by the University Health Network Research Ethics Board (Toronto, ON, Canada; REB 20-5784).

Survey instrument development

The survey tool was developed through an iterative, collaborative process among the study authors after broad consultation of the literature for similar pre-existing instruments, knowledge gaps, and key issues regarding the perioperative use of colloids and crystalloids for intravascular volume expansion in cardiac surgical patients.9,10,13 During this process, the study authors clarified the underlying constructs that individual questions should address, and their design and phrasing. The principal investigator drafted the initial survey, which was reviewed with the study authors. This draft was pretested for clarity and conciseness among three practicing cardiac anesthesiologists at Toronto General Hospital (Toronto, ON, Canada) and changes to wording and question length were made accordingly. The final survey contained 22 questions and three conditional subquestions. Of these questions, seven were open-ended and required respondents to type their answers and comments. This survey was designed to be completed entirely online.

Survey instrument

By clicking the link within the recruitment email, participants were taken to an online survey hosted by REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure web-based platform that adheres to Canadian privacy laws.14,15 The online survey was composed of three sections: (1) Demographics—specialty, number of years in practice, proportion of cardiac-related practice, and geographical location of practice; (2) Personal Practices—fluid management product choices, frequency of administration of different products, and timing of administration; and (3) Opinions—clinician perceptions and beliefs towards different fluid products and their impact on patient outcomes. Total time to completion of the survey was five minutes or less. Survey data were anonymous and transferred to a secure database on a hospital server. The full survey instrument can be found in the Electronic Supplementary Material eAppendix.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics from survey responses were used to identify percentages for count data, means and standard deviations for normally distributed data, and medians with interquartile ranges for nonparametric data. SAS Studio (2021) was used for all quantitative analyses (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Qualitative data analysis was used for free-text responses and comment fields. Free text and comments were analyzed with emerging themes inductively generated from the data by two team members (L. L. and J. B.). This approach uses a thematic analysis based on issues emerging as important from the data itself.16 The study team members met to discuss progress and discrepancies, and to independently verify their findings. Data were organized into descriptive charts, coded, and analyzed by theme to identify concepts and explanations within the data that clarified albumin use patterns.

Results

Characteristics of survey respondents

A total of 25 institutions from across Canada were contacted for participation (Ontario, n = 11; Alberta, n = 2; British Columbia, n = 5; Saskatchewan, n = 1; Manitoba, n = 1; Quebec, n = 4; Nova Scotia, n = 1). A total of 133 survey responses were obtained from 1 June 2021 to 23 June 2021 (Table 1). There was wide representation across age categories with most respondents indicating their specialty as anesthesiologists or anesthesiologists who also practiced as intensivists, although responses were also obtained from surgeons and medical intensivists. The majority of respondents were from Ontario (74/133, 56%) and British Columbia (27/133, 20%), with 10/133 responses each from Quebec (8%) and Nova Scotia (8%). Fewer reponses were obtained from Saskatchewan (6/133, 5%), Manitoba (4/133, 3%), and Alberta (2/133, 2%).

Patterns of individual clinical practice pertaining to resuscitation of cardiac surgical patients

Perioperatively, participants were most likely to employ a primarily crystalloid resuscitation strategy, with albumin used to supplement crystalloids if required (78/133, 59%) (Table 2). A large proportion of clinicians also employed a crystalloid only strategy (48/133, 36%), with 21/133 (16%) never using albumin in the operating room. Of the clinicians who used albumin in the operating room, the majority used it rarely (68/133, 52%) or occasionally (24/133, 18%) and were most likely to use 5% albumin (64/99, 65%) or a combination of 5% and 25% albumin (26/99, 26%). Overall for nonbleeding patients, participants were most likely to use 5% albumin as a first choice colloid, if a colloid were required (96/132, 73%).

A total of 28/133 (21%) respondents did not regularly care for intensive care patients. Of the remaining 105/133 (79%) respondents regularly involved in intensive care management, 31/105 (30%) used albumin occasionally, and 49/105 (47%) used albumin often in the ICU. The majority of respondents used a combination of 5% and 25% albumin in this setting (62/97, 64%).

In terms of the reasons behind product selection, respondents favoured 25% albumin over 5% for enhancement of intravascular oncotic pressure (95/132, 72%), for treatment of edema (43/132, 33%), and for serum albumin replacement in the setting of hypoalbuminemia (20/132, 16%). The vast majority of providers (115/128, 90%) were not aware of defined institutional protocols, or specific indications for albumin use in cardiac surgical patients. Additionally, the vast majority (88/128, 69%) were not aware of society or national guidelines specifying indications for albumin use. Less than 10% of providers identified institutional or national guidelines relevant to albumin transfusion in cardiac surgical patients.

Clinician beliefs and attitudes regarding albumin for fluid resuscitation in cardiac surgical patients

The majority of providers felt it was important to maintain a low total fluid balance in most cardiac surgical patients (102/133, 77%), and that albumin was helpful to achieving this objective compared with crystalloids alone (89/133, 67%). Nevertheless, a large proportion of respondents were undecided or disagreed regarding the utility of albumin for this purpose (41/133, 31%). A minority (< 10%) of respondents felt that there was decreased renal injury, decreased coagulopathy, or decreased mortality with the use of albumin compared with crystalloids. Only a minority of respondents felt that the absence of albumin availability may cause real patient harm (31%). A similar number of respondents felt that the risks or costs of albumin outweighed its potential advantages (42/133, 32%), compared with the number who felt the risks or costs did not outweigh potential advantages (45/133, 34%).

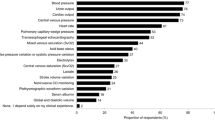

Clinicians articulated reasons for the selection of different albumin formulations in certain circumstances (57 individual comments, Table 3), and offered details regarding their thoughts on the use of defined protocols or guidelines for albumin use (30 individual comments, Table 4). A common theme among responses was the lack of evidence supporting albumin use in this population, although there was significant controversy with a wide variety of opinions observed (Table 4, Figure). Even while acknowledging a lack of supporting evidence, clinicians identified specific situations and patient subpopulations where they felt albumin was of benefit and should be available (94 individual comments, Table 5). When asked to identify research priorities in this area, clinicians frequently wondered about the efficacy of albumin for intravascular volume expansion over crystalloids alone, and questioned whether albumin supplementation resulted in a difference in major clinical outcomes such as mortality and end-organ complications. When asked to identify study outcomes or endpoints that would influence clinical practice, if a comparison of crystalloids and albumin were conducted, clinicians overwhelmingly chose mortality as the most important outcome (Table 6). Nevertheless, a number of clinicians were also concerned with additional end-organ effects, including acute kidney injury, neurologic outcomes, prolonged ventilation due to fluid overload, and new arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation that were thought to be associated with volume overload. Other important outcomes identified were cost-effectiveness, length of stay, and total transfusion needs.

Discussion

Overall, clinicians reported commonly using albumin in cardiac surgical patients. Albumin use in the operating room appears to be limited to a minority of respondents, with 24% using it occasionally or more often. In this environment, 5% albumin was reported to be the formulation of choice. Different practices were reported in the ICU setting, where 62% of respondents stated they utilize albumin occasionally or more often in the care of postoperative cardiac surgical patients. In this setting, both 5% and 25% albumin were frequently used. Although most clinicians clearly identified specific situations and patient subgroups that they perceived benefit from albumin, they nevertheless felt that the primary advantage of albumin is related to avoidance of fluid overload. The majority did not believe that albumin was likely to improve mortality or end-organ complications.

Many clinicians remarked that a perceived benefit of albumin in the ICU was to promote intravascular oncotic pressure and mobilize interstitial fluid. This is similar to the findings of Aronson et al. in their practice survey of fluid resuscitation practices in USA healthcare providers,10 where the majority of clinicians (≥ 90%) disagreed or felt ambivalent that using albumin improved mortality or end-organ complications; however, it remained popular because of its perceived minimization of interstitial volume overload and sustained intravascular volume expansion. In our survey, 15% of clinicians felt the use of 25% albumin for serum albumin replacement was justified and appeared to associate this with better outcomes, despite the results of the recent Albumin to Prevent Infection in Chronic Liver Failure (ATTIRE) trial.17 In ATTIRE, hospitalized patients with decompensated cirrhosis and a serum albumin level less than 30 g·L−1 were randomized to either daily 20% albumin or standard care. There was a greater rate of severe or life-threatening serious adverse events in the albumin group, especially pulmonary edema. This suggests that the practice of using 25% albumin to achieve a less positive overall positive fluid balance in cardiac surgical patients at high-risk of pulmonary edema and serious adverse events is likely to need further study given the contradictory evidence in other populations.

The majority of clinicians appeared to agree that the routine use of albumin in nonbleeding cardiac surgery patients was unlikely to be of significant benefit. Nevertheless, local culture and practice were seen as difficult to counter by individual clinicians seeking to take a more restrictive approach to their personal albumin prescribing. When asked about reasons for albumin prescribing, one senior cardiac anesthesiologist and intensivist remarked that a strong contributing factor was frequent requests for albumin from bedside nursing staff, despite a lack of evidence supporting increased efficacy over crystalloids. Therefore, the implementation of practice changes based on new evidence, especially policies designed to curtail liberal albumin administration, should involve nursing and other healthcare colleagues to better enable a uniform culture of transfusion avoidance and blood product conservation. Additionally, there may be ingrained beliefs within Canadian anesthesia culture related to the perceived advantages of colloid resuscitation fluids that are worth re-examining.

The widespread use of albumin in cardiac surgical patients may be seen as surprising given the numerous large high-quality randomized controlled trials in general ICU patients showing no major advantage of albumin use over crystalloid use.18,19,20 These large high-quality studies have in turn resulted in more narrow indications for albumin use supported by CBS according to the quality of available evidence.7 The results of this survey reinforce the idea that providers caring for cardiac surgical patients see them as different from the general ICU population, in that studies from that population are not seen as directly translatable. Small randomized clinical trials in the adult cardiac surgery population have evaluated the use of albumin as both part of the pump prime and for hemodynamic support, but the published trial data are limited by nondefinitive studies, with the largest including only 203 patients.21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40 The Albumin in Cardiac Surgery (ALBICS) study has completed enrolment (1,386 patients; NCT02560519), and compared 20% albumin diluted in Ringer’s lactate to a final concentration of 4% (to avoid the potential for hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis with 5% albumin formulations) to Ringer’s lactate alone for pump prime and volume resuscitation in the first 24 postoperative hours. This trial may help clarify the risk-benefit ratio of albumin in this patient population.

Clinicians were, in general, supportive of the idea of curtailing routine albumin use, with numerous respondents commenting on the lack of evidence supporting efficacy over crystalloids. Many also felt a strong need to better understand the specific circumstances under which albumin could be beneficial. There is interest in high-quality studies on albumin use in high-risk cardiac surgery patient subgroups to better understand its indications and benefits, such as in patients with underlying renal and hepatic impairments. The majority of respondents (69%) did not feel that the absence of albumin would likely lead to patient harm, suggesting that a randomized clinical trial with an arm where albumin use was absent or restricted compared with an arm with albumin available would be acceptable to most clinicians in Canada, even in high-risk patient subgroups.

Limitations of our study relate to our survey methodology.41 Surveys are useful tools for collecting data that rely on self-reporting of beliefs, opinions, and experiences. Nevertheless, they are not optimal for thorough qualitative analysis, and there is a lack of consensus regarding the optimal reporting criteria for survey research.41 No accurate sampling frame is available for our target population, as multiple clinicians across different specialties at each institution are likely to be involved in the perioperative care of cardiac surgical patients. A recent survey recruiting Canadian academic cardiac anesthesiologists estimated their sampling cohort as n = 346, and concluded that community cardiac anesthesiologists likely represent a minority of practitioners in Canada.42 Based on this prior estimate, it is likely that our survey sample is representative of our target population.43 Our primary goal was to obtain a geographically diverse, representative sample from major cardiac surgical centres across Canada to understand the practices of cardiac anesthesiologists and dedicated cardiovascular intensivists. Sampling methods such as ours, which include convenience sampling followed by peer recruitment and “snowball” sampling, have been shown to sometimes provide accurate, meaningful results in these situations.12 Given the variability in our sample in terms of age, proportion of time spent caring for cardiac surgical patients, and geographic location, we feel we have obtained a representative sample that also adequately reflects the diversity of opinion within the Canadian anesthesia community. We acknowledge that a limitation of this approach is our inability to evaluate noncoverage and nonresponse errors. There is also a disproportionate geographical bias to clinicians practicing in Ontario or British Columbia. Nevertheless, our sample size of 133 respondents appears sufficient given the frequent repetition of highly divergent opinions and themes observed in our survey responses, suggesting data saturation was achieved for our qualitative analysis. The availability of reliable, valid data on clinician practices and perceptions towards albumin use in Canada is critical for the design of clinically relevant future studies in this area.

Conclusion

Canadian clinicians reported commonly using both 5% and 25% albumin to supplement crystalloids for the resuscitation of cardiac surgical patients, especially during ICU care. There is variability in clinician perception of the benefits of albumin over crystalloids, with an acknowledgement of the lack of high-quality supporting evidence for this clinical practice among the majority of cardiac anesthesiologists and cardiovascular intensivists. Clinicians are most pressed to understand the impact of albumin on the outcomes of high-risk patient subgroups, and are most interested in studies examining major clinical outcomes such as mortality and end-organ complications.

References

Grundmann R, Heistermann S. Postoperative albumin infusion therapy based on colloid osmotic pressure: a prospectively randomized trial. Arch Surg 1985; 120: 911-5.

Miller TE, Myles PS. Perioperative fluid therapy for major surgery. Anesthesiology 2019; 130: 825-32.

Lewis SR, Pritchard MW, Evans DJ, et al. Colloids versus crystalloids for fluid resuscitation in critically ill people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000567.pub7.

Lyu PF, Murphy DJ. Economics of fluid therapy in critically ill patients. Curr Opin Crit Care 2014; 20: 402-7.

Barron ME, Wilkes MM, Navickis RJ. A systematic review of the comparative safety of colloids. Arch Surg 2004; 139: 552-63.

Hanley C, Callum J, Karkouti K, Bartoszko J. Albumin in adult cardiac surgery: a narrative review. Can J Anesth 2021; 68: 1197-213.

Clarke G, Yan M. Clinical guide to transfusion: albumin 2018. Available from URL: https://professionaleducation.blood.ca/en/transfusion/guide-clinique/albumin (accessed January 2022).

Hanley C, Callum J, McCluskey S, Karkouti K, Bartoszko J. Albumin use in bleeding cardiac surgical patients and associated patient outcomes. Can J Anesth 2021; 68: 1514-26.

Protsyk V, Rasmussen BS, Guarracino F, Erb J, Turton E, Ender J. Fluid management in cardiac surgery: results of a survey in European cardiac anesthesia departments. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2017; 31: 1624-9.

Aronson S, Nisbet P, Bunke M. Fluid resuscitation practices in cardiac surgery patients in the USA: a survey of health care providers. Perioper Med (Lond) 2017; https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-017-0071-6.

Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2014.

Reichel D, Morales L. Surveying immigrants without sampling frames – evaluating the success of alternative field methods. Comp Migr Stud 2017; https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-016-0044-9

Miller TE, Bunke M, Nisbet P, Brudney CS. Fluid resuscitation practice patterns in intensive care units of the USA: a cross-sectional survey of critical care physicians. Perioper Med (Lond) 2016; https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-016-0035-2.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42: 377-81.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208.

Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods 2017; https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847.

China L, Freemantle N, Forrest E, et al. A randomized trial of albumin infusions in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 808-17.

Finfer S, Bellomo R, Boyce N, et al. A comparison of albumin and saline for fluid resuscitation in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 2247-56.

Cook D. Is albumin safe? N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 2294-6.

Caironi P, Tognoni G, Masson S, et al. Albumin replacement in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 1412-21.

Van der Linden P, De Villé A, Hofer A, Heschl M, Gombotz H. Six percent hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.4 (Voluven®) versus 5% human serum albumin for volume replacement therapy during elective open-heart surgery in pediatric patients. Anesthesiology 2013; 119: 1296-309.

Tigchelaar I, Gallandat Huet RC, Boonstra PW, van Oeveren W. Comparison of three plasma expanders used as priming fluids in cardiopulmonary bypass patients. Perfusion 1998; 13: 297-303.

Skillman JJ, Restall DS, Salzman EW. Randomized trial of albumin vs. electrolyte solutions during abdominal aortic operations. Surgery 1975; 78: 291-303.

Skhirtladze K, Base EM, Lassnigg A, et al. Comparison of the effects of albumin 5%, hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.4 6%, and Ringer's lactate on blood loss and coagulation after cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth 2014; 112: 255-64.

Scott DA, Hore PJ, Cannata J, Masson K, Treagus B, Mullaly J. A comparison of albumin, polygeline and crystalloid priming solutions for cardiopulmonary bypass in patients having coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Perfusion 1995; 10: 415-24.

Saunders CR, Carlisle L, Bick RL. Hydroxyethyl starch versus albumin in cardiopulmonary bypass prime solutions. Ann Thorac Surg 1983; 36: 532-9.

Sade RM, Stroud MR, Crawford FA Jr, Kratz JM, Dearing JP, Bartles DM. A prospective randomized study of hydroxyethyl starch, albumin, and lactated Ringer’s solution as priming fluid for cardiopulmonary bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1985; 89: 713-22.

Riegger LQ, Voepel-Lewis T, Kulik TJ, et al. Albumin versus crystalloid prime solution for cardiopulmonary bypass in young children. Crit Care Med 2002; 30: 2649-54.

Rex S, Scholz M, Weyland A, Busch T, Schorn B, Buhre W. Intra- and extravascular volume status in patients undergoing mitral valve replacement: crystalloid vs. colloid priming of cardiopulmonary bypass. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2006; 23: 1-9.

Palanzo DA, Parr GV, Bull AP, Williams DR, O’Neill MJ, Waldhausen JA. Hetastarch as a prime for cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg 1982; 34: 680-3.

Ohqvist G, Settergren G, Lundberg S. Pulmonary oxygenation, central haemodynamics and glomerular filtration following cardiopulmonary bypass with colloid or non-colloid priming solution. Scand J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1981; 15: 257-62.

Niemi TT, Suojaranta-Ylinen RT, Kukkonen SI, Kuitunen AH. Gelatin and hydroxyethyl starch, but not albumin, impair hemostasis after cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg 2006; 102: 998-1006.

Mastroianni L, Low HB, Rollman J, Wagle M, Bleske B, Chow MS. A comparison of 10% pentastarch and 5% albumin in patients undergoing open-heart surgery. J Clin Pharmacol 1994; 34: 34-40.

Marelli D, Paul A, Samson R, Edgell D, Angood P, Chiu RC. Does the addition of albumin to the prime solution in cardiopulmonary bypass affect clinical outcome? A prospective randomized study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1989; 98: 751-6.

London MJ, Franks M, Verrier ED, Merrick SH, Levin J, Mangano DT. The safety and efficacy of ten percent pentastarch as a cardiopulmonary bypass priming solution. A randomized clinical trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1992; 104: 284-96.

London MJ, Ho JS, Triedman JK, et al. A randomized clinical trial of 10% pentastarch (low molecular weight hydroxyethyl starch) versus 5% albumin for plasma volume expansion after cardiac operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1989; 97: 785-97.

Liou HL, Shih CC, Chao YF, et al. “Inflammatory response to colloids compared to crystalloid priming in cardiac surgery patients with cardiopulmonary bypass.” Chin J Physiol 2012; 55: 210-8.

Lee EH, Kim WJ, Kim JY, et al. Effect of exogenous albumin on the incidence of postoperative acute kidney injury in patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery with a preoperative albumin level of less than 4.0 g/dl. Anesthesiology 2016; 124: 1001-11.

Jenkins IR, Curtis AP. The combination of mannitol and albumin in the priming solution reduces positive intraoperative fluid balance during cardiopulmonary bypass. Perfusion 1995; 10: 301-5.

Hosseinzadeh Maleki M, Derakhshan P, Rahmanian Sharifabad A, Amouzeshi A. Comparing the effects of 5% albumin and 6% hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.4 (voluven) on renal function as priming solutions for cardiopulmonary bypass: a randomized double blind clinical trial. Anesth Pain Med 2016; https://doi.org/10.5812/aapm.30326.

Bennett C, Khangura S, Brehaut JC, et al. Reporting guidelines for survey research: an analysis of published guidance and reporting practices. PLoS Med 2010; https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001069.

Spence J, Belley-Côté E, Devereaux PJ, et al. Benzodiazepine administration during adult cardiac surgery: a survey of current practice among Canadian anesthesiologists working in academic centres. Can J Anesth 2018; 65: 263-71.

Ebert JF, Huibers L, Christensen B, Christensen MB. Paper- or web-based questionnaire invitations as a method for data collection: cross-sectional comparative study of differences in response rate, completeness of data, and financial cost. J Med Internet Res 2018; https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.8353.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to study concept, manuscript content, manuscript writing, and final review of the paper.

Funding statement

Justyna Bartoszko, MD, MSc: in part supported by a merit award from the Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, University of Toronto. Keyvan Karkouti, MD, MSc: in part supported by a merit award from the Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, University of Toronto; has received research support, honoraria, or consultancy for speaking engagements from Octapharma, Instrumentation Laboratory, and Bayer. Duminda N. Wijeysundera, MD, PhD: in part supported by a merit award from the Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, University of Toronto and the Endowed Chair in Translational Anesthesiology Research from St. Michael’s Hospital and the University of Toronto. Jeannie Callum, MD: research support from Canadian Blood Services and Octapharm. Damon C. Scales, MD, PhD: has received operating grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Philip M. Jones, Deputy Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, L., McCluskey, S.A., Law, M. et al. Albumin use for fluid resuscitation in cardiac surgical patients: a survey of Canadian perioperative care providers. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 69, 818–831 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-022-02237-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-022-02237-w