Abstract

Purpose

Safe perioperative care remains a large public healthcare problem in low- and middle-income countries. Anesthesia care provided by trained professionals is one of the essential determinants to address this situation. This article reports the design and implementation of a focused anesthesia educational program for nurses in Chad.

Method

This program consisted of four full-time courses of one month each, taught in a local hospital. The program included supervised practice in the operating room and post-anesthesia recovery room, skills lab simulation training, high fidelity crisis simulation, theoretical classes, integration sessions, evaluations, and structured feedback sessions.

Results

Seven male nurses, aged 28–40 yr, were accepted and successfully completed the program. The median [interquartile range] students’ global satisfaction with the program was high (86 [85–93]%). Cognitive and skills assessment improved significantly after the program. Students subsequently worked in city and district hospitals performing essential and emergency surgical interventions.

Conclusions

This is a novel south–south academic cooperation program for nurses in Chad. The program evaluation indicated a high level of satisfaction, effective cognitive and skills learning, and changes in clinical behaviour. Addressing the lack of adequate provision of anesthesia care is a task still to be faced, and this program depicts a bridge alternative until formal educational programs are implemented in the country.

Résumé

Objectif

Des soins périopératoires sécuritaires demeurent un important problème de santé publique dans les pays à faible et à moyen revenu. Les soins anesthésiques offerts par des professionnels formés constituent l’un des éléments déterminants essentiels pour régler le problème. Cet article rapporte la conception et la mise en œuvre d’un programme spécialisé de formation en anesthésie s’adressant au personnel infirmier au Tchad.

Méthode

Ce programme était composé de quatre cours intensifs d’une durée d’un mois chacun, donnés dans un hôpital local. Le programme comportait une pratique supervisée en salle d’opération et en salle de réveil, des séances pratiques en laboratoire de simulation, une simulation de crise haute fidélité, des classes théoriques, des séances d’intégration, des évaluations et des séances de rétroaction structurées.

Résultats

Sept infirmiers âgés de 28 à 40 ans ont été acceptés dans le programme et l’ont terminé avec succès. La satisfaction globale moyenne [écart interquartile] des étudiants était élevée (86 [85–93] %). L’évaluation cognitive et des connaissances s’est considérablement améliorée après avoir suivi le programme. Les étudiants ont par la suite travaillé dans des hôpitaux de ville et de district réalisant des interventions chirurgicales essentielles et urgentes.

Conclusion

Il s’agit d’un programme de coopération universitaire sud-sud innovant au Tchad. L’évaluation du programme a indiqué un niveau élevé de satisfaction, un apprentissage efficace au niveau cognitif et des compétences, ainsi que des changements au niveau du comportement clinique. Il reste encore beaucoup de travail pour régler le problème suscité par l’absence d’une offre adéquate de soins anesthésiques, et ce programme décrit une alternative temporaire intéressante jusqu’à ce que des programmes de formation formels soient mis en œuvre dans ce pays.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Perioperative morbidity and mortality remains a major public healthcare problem in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC).1 Even though infectious diseases and malnutrition represent high disease burdens, surgical diseases present a growing trend in disability-adjusted life years (DALY).2,3 Among LMICs, those in Africa have the highest burden of surgical DALY per 1,000 people,4 and it is estimated that 143 million additional surgeries are needed in LMIC each year to decrease this burden.2 In some countries, 94% of the population does not have access to safe, timely, and affordable surgical and anesthesia care.2 Various barriers to addressing this problem have been identified, including a lack of human and technical resources, untimely access to healthcare, financial burdens, and “brain drain”.5 Safe perioperative care, provided by anesthesia professionals, is one of the essential determinants to address this situation.2,6,7

Even though medical missions are providing aid to partially address this important burden of disease, capacity building projects are trying to develop a long-term solution.8,9 In this area, multiple academic collaborations have been successfully developed to strengthen the anesthesia workforce and provide theoretical and practical foundations adapted to the LMIC requirements.10,11,12,13,14,15,16 Despite this, no internationally validated training programs for non-physician anesthesia providers (NPAPs) have been proposed for LMIC with a wide range of designs, methodologies, and structures implemented worldwide.10,13,17

Chad is a landlocked sub-Saharan African country. Its population is approximately 14 million people, with a per capita gross national income of 720 USD per year.18 It ranks 186 (of 188) in the Human Development Index.19 Life expectancy is 51.9 yr, maternal mortality rate is 856/100,000 live births, and up to 30% of children are malnourished.20 A recent anesthesia workforce survey found that there is only one anesthesiologist and 22 NPAP in Chad, equating to 0.01 providers per 100,000 population.21 There are no formal anesthesia residency programs, nor training programs for NPAP; most are trained in neighbouring countries or through occasional educational initiatives. The lack of trained anesthesia workforce is overwhelming. Throughout the country, there are many untrained anesthesia providers exponentially increasing the risk of perioperative complications in a vulnerable population.

The Complexe Hospitalier-Universitaire Le Bon Samaritain (CHU-BS) is a privately owned tertiary-care hospital in the Chadian capital N’Djamena, a health centre founded in 2007 by the Jesuit Mission in West Africa. The hospital has 147 beds and in 2017 there were 5,241 hospital discharges. It has a medical and nursing school, and has participated successfully in previous academic partnerships.22

In 2009, a Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (PUC) assistant professor undertook the first collaboration experience in the CHU-BS facilities. This personal initiative led to subsequent medical missions from the Chilean university involving a growing number of faculty members and students. Because of the successful earlier experience, and after eight years of informal health cooperation between these institutions, a formal academic collaboration agreement was signed to create capacity building projects in Chad.

Considering the growing surgical need in the country, an almost complete lack of certified anesthesia providers, and no availability of formal training, we designed and implemented a basic anesthesia educational program for nurses in Chad that focused on the most relevant content to safely address most common surgical procedures. The main objective of this article is to report this experience, and show the educational impact of this program.

Methods

Ethics

The institutional review board of Facultad de Medicina, PUC approved this report (Comité de Ética en Investigación; approval number 180418001) and waived the need of any informed consent. The Chadian host institution’s director authorized the use of the information provided in this article, as no research ethics review board was available at CHU-BS.

Needs assessment

To implement an educational program tailored to the context, a formal needs assessment was developed. It included surveys to key stakeholders (surgeons, gynecologists, administrative staff, hospital directors, and current NPAP), an analysis of operating room (OR) registries of the previous six months (number and types of surgery, anesthesia techniques, and perioperative outcomes), availability of anesthetic supplies in rural and city hospitals (drugs, ventilators, oxygen, monitors, and postoperative care), access to electricity, access to the internet, and suitable classrooms.

Anesthetic supplies available in CHU-BS are listed in Table 1. Other district hospitals surveyed have fewer human and technical resources. Despite the fact that CHU-BS is an equipped referral hospital, there is just one NPAP available, who lives in the facility and is on call 24/7.

Training program design and implementation

In Chile, a multicentre team was formed, including anesthesiologists from PUC, Universidad de Chile, and Hospital de Osorno. Both universities have more than 50 years of experience in anesthesiology residency programs. Although a blended (i.e., online and face-to-face) learning program would have been a useful methodology, it was discarded because consistent internet access was lacking. The program was designed focusing on available anesthesia techniques (ketamine anesthesia, spinal anesthesia, and general anesthesia) and the most common surgical case load, including Bellwether procedures23,24 (i.e., proxy procedures used to describe the delivery of essential surgical care, including Cesarean delivery, laparotomy, and treatment of open fractures) and other common elective and urgent surgeries (e.g., hysterectomy, thyroid surgery, hernia repair, hydrocele, and burn debridement). Neurosurgery, cardiothoracic, and vascular surgery were excluded because surgical resolution was not possible in this context. Although regional blocks, epidural anesthesia, and postoperative mechanical ventilation were considered in the design, they were excluded from the program, considering the limited time, safety concerns, and learning curves.

Admission requirements included a valid Chadian nursing diploma (obtained after three years of training and a national board approved exam), French language skills, five years of clinical experience in surgical wards or OR (no anesthesia experience required), a recommendation letter, and an interview with the hospital director.

Because of schedule constraints of both Chilean and Chadian participants, a face-to-face learning program was designed, consisting of four full-time courses (11 hr a day, five days a week) of one month each, given at the CHU-BS campus. The courses were scheduled in March (introduction, basic physiology, and preanesthetic evaluation), July (pharmacology, monitoring, airway management, and resuscitation), September (anesthetic techniques, common diseases, and postoperative care) and December (pediatric and obstetric anesthesia, critical events, and anesthesia for specific surgeries) 2017. Each course was by taught by three Chilean faculty members or two faculty members and a senior year resident. Housing facilities were arranged for out of town students. During non-course intervals, students resumed their usual work at home hospitals and prepared for the next course with a selected bibliography given beforehand. An email-based communication channel was established for direct contact with students. A graduation ceremony was scheduled for March 2018. The complete curriculum is detailed in the eTable (available as Electronic Supplementary Material). The Chadian Ministry of Health was informed of this pilot initiative and endorsed participation of individuals from public hospitals. Nevertheless, formal approval of the program by the Ministry of Health was not granted pending further assessment.

In the mornings, trainees performed progressive clinical supervised practice in the OR and postanesthesia recovery room. In the afternoon, the teaching sessions included theoretical classes, skills lab simulation training, high fidelity crisis simulation, and integration sessions. Multiple choice questions and long answer essays were used for cognitive evaluations. Direct observation of procedural skills (DOPS) assessment forms25 and real patient performance evaluation were used for skills, attitudes, and clinical reasoning assessments. Structured feedback sessions were included every two weeks.26 Pass scores (60%) were set according to the PUC healthcare sciences education centre’s standards.

The cognitive assessment scheme included diagnostic tests that were administered pre-module, mid-term tests at the end of the second week, a final exam at the end of the fourth week, with a post-test (for retention) administered at the beginning of the next module (two months between each).

Program evaluation

Anonymous satisfaction surveys were given to students and teachers after each course was conducted. The educational impact was measured by analyzing the progression of grades in diagnostic, mid-term, final, and retention tests of each course. Pre- and post-training DOPS assessment forms25 were applied following the simulation of airway management and spinal anesthesia on manikins. The number of real cases performed by each student was registered. Because there were no previous data registries, the impact on patient outcomes could not be analyzed. After the final course, a logbook was provided for each student. This was not included in the assessment program, but was used as a feedback instrument to the program organizers. The logbook had to be completed with each anesthesia case delivered in their hospitals from the end of the last course to the graduation ceremony (three months).27 The logbook variables included patient age, surgical plan, anesthetic plan, emergency or elective procedure, and perioperative complications (major adverse cardiac events, significant desaturation or hypotension, airway management problem, failed spinal anesthesia, aspiration, and death).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with Minitab version 17 Statistical Software (Minitab Inc, State College, PA, USA). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test was applied, and because of non-parametric distribution, non-normal statistics were used. Data are presented as median [interquartile range (IQR)] or percentage (%) accordingly. Statistical analysis included Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis test with a Bonferroni’s correction when appropriate. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

Seven male nurses, aged 28–40 yr, were accepted in the program. Five had no previous experience in anesthesia, and two had received some informal training. All students completed and passed the program with 100% attendance in 2017. Three worked in CHU-BS, three worked in district hospitals, and one in another referral centre.

The total cost of the program, including airline tickets, educational materials, housing, and operational costs, was 36,554 USD or 5,222 USD per student. The program was financed by the supporting Chilean and Chadian institutions. Students were not charged for the program.

Satisfaction

Median [IQR] students’ global satisfaction with the program was 86 [85–93]%. The highest satisfaction was with “evaluation methods” (86 [86–100]%) and “organization” (93 ([79–100]%). The lowest scores were obtained for “feedback” (82 [78–93]%) and “infrastructure” (78 [71–100]%). Examples of selected free choice comments from questionnaires are shown in Table 2. Positive aspects included the integrated theoretical-practical approach and simulation training. Negative aspects included the teachers’ French language fluency and the coordination between courses.

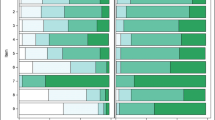

Knowledge

All students passed the four courses. The progression of theoretical tests grades is illustrated in Fig. 1. Diagnostic tests were significantly lower than the other three tests. Retention test scores were not statistically different from final exam scores. Remediation sessions were offered to students who failed retention tests.

Pre and post-training DOPS scores in airway management and spinal anesthesia are illustrated in Figs 2 and 3, respectively. Prior to training, no student obtained the minimum pass score in airway management, and just one in spinal anesthesia. Post training, all students passed both tests.

During the four-month training period, each student successfully completed at least 30 spinal anesthetics, 20 bag-mask ventilations, 20 ketamine sedation cases, and ten orotracheal intubations.

Clinical behaviour

Students verbally reported the presence of mainly untrained anesthesia providers in their workplace hospitals, with preoperative evaluations rarely performed, inadequate anesthesia techniques, and insufficient monitoring. As an example, most elective Cesarean deliveries were performed with ketamine sedation, despite availability of spinal anesthesia. Logbook results are shown in Table 3. One student who worked in a rural hospital, being the sole anesthesia professional in the hospital, performed the highest number of procedures, 265 cases in 70 days.

Logbook entries revealed that 13% of patients were pediatric, and the most common surgeries were Cesarean deliveries, hernia repair, uterine curettage, emergency laparotomies, trauma, and surgical debridement of burns. Their caseloads were composed mostly of Bellwether procedures. Almost 50% were emergency surgeries, and there was only one reported major complication, an intraoperative cardiac arrest secondary to uncontrollable obstetric hemorrhage (0.15%). Twenty-one (100%) elective Cesarean deliveries were performed with spinal anesthesia. In emergency Cesarean deliveries, 12 (9%) were performed with general anesthesia and rapid sequence intubation because of eclampsia, 106 (82%) with spinal anesthesia, and 12 (9%) with ketamine anesthesia.

Discussion

This basic anesthesia training program is novel for nurses in Chad, and was successfully completed by seven students. Program evaluation indicated a high level of satisfaction, effective cognitive and skills learning, and changes in clinical behaviour. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first south–south academic cooperation program reported in the anesthesiology field.

South–south cooperation initiatives are considered innovative and inclusive development strategies.28 In south–south cooperations, countries from the Global South “share knowledge, skills, expertise, and resources to meet their development goals through concerted efforts”.29 Multiple benefits have been described in the literature, including the introduction of context-sensitive interventions, the potential resolution of shared problems, and a higher sense of ownership among beneficiaries.30 The United Nations Development Program has actively endorsed these partnerships to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals for 2030.31

Kempthorne reported that approximately 22 Chadian healthcare professionals work in the anesthesiology field.21 The lack of anesthesia-trained workforce in Chad is huge. Many educational interventions have been proposed to address this kind of gap, from five-day brief courses17,32 to full training programs10 certified by local authorities. Our program offers a reasonable alternative and might serve as a bridge solution for training nurses intensively and efficiently to provide anesthesia for common procedures.

Addressing the lack of adequate anesthesia care is an urgent task to be faced as a global society, as many suffer from a lack of access to safe surgical care because of few resources and an insufficient and/or untrained workforce. This initiative illustrates an efficient response to this challenge that could be viewed as a bridge solution for a critical need, where there are extremely few trained professionals and high numbers of untrained providers delivering potentially hazardous anesthetic care. It could be argued that this kind of initiative may risk increasing the number of unqualified anesthesia providers as the program did not provide complete NPAP training. Nevertheless, in our opinion, in situations of extreme deprivation, a partial but feasible training is better than no training at all.

Despite this positive intervention, limitations must be addressed. A language barrier was perceived, even though all teachers were trained in French before the implementation of the program. Future versions will ensure teachers have an appropriate language (i.e., Diplôme Approfondi de Langue Française) certification. In addition, because reliable registries of the pre-intervention status were not available, we could not assess the clinical impact and perform a safety evaluation. To overcome this limitation, logbooks were provided to students to enable analysis of post-intervention registries. The use of a logbook as a measuring tool is based on self-reporting, therefore data could be incomplete, biased, or deliberately omitted. Future versions of this program should include more comprehensive evaluation instruments,33 including workplace-based assessments,34 adherence to preoperative evaluation, and checklists.35

The competency of trained students and safety issues must be further evaluated to assess the real impact and safety of this program. This type of training cannot replace formal education programs for anesthesiologists and NPAPs. All efforts must be made to establish such programs as soon as possible. While this task is achieved, creative training programs like the one presented in this report may serve to alleviate the urgent deficit of trained professionals.

This initiative may lack sustainability because of financial and personnel time cost. Nevertheless, as this is a pilot course, it serves as a learning opportunity for all parties, and lessons can be drawn to optimize future cooperation projects between partners. For instance, participation of trained Chadian professionals, better use of electronic resources, and educational design optimization could improve the feasibility and lower the costs of future educational projects.

This program was the result of nine years of collaborative work between institutions, and people from Chile and Chad are truly committed to this alliance. Those years of collaboration have helped make this relationship more horizontal. The achievements and knowledge that were brought about by this training program may serve as a platform on which to develop further projects, aiming at short-, medium-, and long-term outcomes. A Safer Anaesthesia From Education refresher course36,37 (a continuous medical education program) and a pain and postoperative care course are being planned for 2019. An updated version of this program may be offered in 2020. In the medium and long term, we are considering interventions to promote adverse events registries, safety policies, the creation of a nationwide anesthesia association, and stimulate the contact with NPAPs of neighbouring countries. Those goals should be chosen together, considering the interests, strengths, and weakness of the different parties. International cooperation should not be understood only as knowledge and resources transfer, but also as advocacy, mentoring, and local involvement to be sustainable.

In conclusion, we have presented the educational impact of a novel south–south academic cooperation program. This successful initiative forges the possibility of expanding this collaboration and increasing the supply of healthcare training programs in Chad and similar countries, based on the country’s needs and adapted to their healthcare reality.

References

Sobhy S, Zamora J, Dharmarajah K, et al. Anaesthesia-related maternal mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2016; 4: e320-7.

Meara JG, Leather AJ, Hagander L, et al. Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet 2015; 386: 569-624.

Ologunde R, Maruthappu M, Shanmugarajah K, Shalhoub J. Surgical care in low and middle-income countries: burden and barriers. Int J Surg 2014; 12: 858-63.

Ozgediz D, Jamison D, Cherian M, McQueen K. The burden of surgical conditions and access to surgical care in low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ 2008; 86: 646-7.

Bharati SJ, Chowdhury T, Gupta N, Schaller B, Cappellani RB, Maguire D. Anaesthesia in underdeveloped world: present scenario and future challenges. Niger Med J 2014; 55: 1-8.

Huber B. Finding surgery’s place on the global health agenda. Lancet 2015; 385: 1821-2.

Davies JI, Meara JG. Global surgery — going beyond the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2015; 386: 507-9.

White MC. Pro: Pure service delivery is still needed in global surgery missions. Can J Anesth 2017; 64: 347-52.

Evans FM, Nabukenya MT. Con: Pure service delivery is no longer needed in global surgical missions. Can J Anesth 2017; 64: 353-7.

Rosseel P, Trelles M, Guilavogui S, Ford N, Chu K. Ten years of experience training non-physician anesthesia providers in Haiti. World J Surg 2010; 34: 453-8.

Riviello R, Ozgediz D, Hsia RY, Azzie G, Newton M, Tarpley J. Role of collaborative academic partnerships in surgical training, education, and provision. World J Surg 2010; 34: 459-65.

Lipnick M, Mijumbi C, Dubowitz G, et al. Surgery and anesthesia capacity-building in resource-poor settings: description of an ongoing academic partnership in Uganda. World J Surg 2013; 37: 488-97.

Olufolabi AJ, Atito-Narh E, Eshun M, Ross VH, Muir HA, Owen MD. Teaching neuraxial anesthesia techniques for obstetric care in a Ghanaian referral hospital: achievements and obstacles. Anesth Analg 2015; 120: 1317-22.

Durieux ME. But what if there are no teachers …? Anesthesiology 2014; 120: 15-7.

Kattan E, Kuroiwa A, Lopez R. International cooperation. Where are we, and where are we heading to? (Spanish). Rev Med Chil 2017; 145: 783-9.

Chellam S, Ganbold L, Gadgil A, et al. Contributions of academic institutions in high income countries to anesthesia and surgical care in low- and middle-income countries: are they providing what is really needed? Can J Anesth 2018; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-018-1258-0.

Schwartz KR, Fredricks K, Al Tawil Z, et al. An innovative safe anesthesia and analgesia package for emergency pediatric procedures and surgeries when no anesthetist is available. Int J Emerg Med 2016; 9: 16.

The World Bank. Chad Data. Available from URL: https://data.worldbank.org/country/chad (accessed February 2019).

United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2016. Available from URL: https://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2016_human_development_report.pdf (accessed February 2019).

World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2014. Available from URL: www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2014/en (accessed February 2019).

Kempthorne P, Morriss WW, Mellin-Olsen J, Gore-Booth J. The WFSA Global Anesthesia Workforce Survey. Anesth Analg 2017; 125: 981-90.

Salvi PF, Balducci G, Dente M, et al. Experimental teaching program on cooperation between “Sapienza” University at Rome and the University Hospital “Le Bon Samaritain” in N’Djamena, Chad (Italian). Ann Ital Chir 2012; 83: 273-6.

O’Neill KM, Greenberg SL, Cherian M, et al. Bellwether procedures for monitoring and planning essential surgical care in low- and middle-income countries: caesarean delivery, laparotomy, and treatment of open fractures. World J Surg 2016; 40: 2611-9.

Juran S, Gruendl M, Marks IH, et al. The need to collect, aggregate, and analyze global anesthesia and surgery data. Can J Anesth 2019; 66: 218-29.

Delfino AE, Chandratilake M, Altermatt FR, Echavarria G. Validation and piloting of direct observation of practical skills tool to assess intubation in the Chilean context. Med Teach 2013; 35: 231-6.

Pérez G, Kattan E, Collins L, et al. Assessment for learning: experience in an undergraduate medical theoretical course (Spanish). Rev Med Chil 2015; 143: 329-36.

Shah S, Ross O, Pickering S, Knoble S, Rai I. Tablet e-logbooks: four thousand clinical cases and complications e-logged by 14 nondoctor anesthesia providers in Nepal. Anesth Analg 2017; 125: 1337-41.

United Nations Development Programme. South-South cooperation. Available from URL: http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/development-impact/south-south-cooperation.html (accessed February 2019).

United Nations Office for South-South Cooperation. About South-South and Triangular Cooperation. 2018. Available from URL: https://www.unsouthsouth.org/about/about-sstc/ (accessed February 2019).

du Toit L, Couper I, Peersman W, de Maeseneer J. South-South Cooperation in health professional education: a literature review. Afr J Health Prof Educ 2017; 9: 3-8.

United Nations Developement Programme. Sustainable Development Goals. Available from URL: http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html (accessed Februay 2019).

Burke TF, Suarez S, Senay A, et al. Safety and feasibility of a ketamine package to support emergency and essential surgery in Kenya when no anesthetist is available: an analysis of 1216 consecutive operative procedures. World J Surg 2017; 41: 2990-7.

Epstein RM. Assessment in medical education. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 387-96.

Norcini JJ, Blank LL, Duffy FD, Fortna GS. The mini-CEX: a method for assessing clinical skills. Ann Intern Med 2003; 138: 476-81.

Lacassie HJ, Ferdinand C, Guzmán S, Camus L, Echevarria GC. World Health Organization (WHO) surgical safety checklist implementation and its impact on perioperative morbidity and mortality in an academic medical center in Chile. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016; 95: e3844.

Association of Anaesthetists. Safer Anaesthesia From Education. Available from URL: https://www.aagbi.org/international/safer-anaesthesia-education-safe/reports (accessed February 2019).

World Federation of Societies of Anaesthesiologists. Safer Anaesthesia From Education (SAFE). Available from URL: https://www.wfsahq.org/wfsa-safer-anaesthesia-from-education-safe (accessed February 2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank Jaime Campusano and Roberto Zamorano (anesthesiologists from the Departamento de Anestesiología, Hospital Base de Osorno) for helping develop the second course of the program; Fernando Reyes, Rodrigo Gutierrez, and Jaime Godoy (anesthesiologists from the Departamento de Anestesiología y Reanimación, Hospital Clínico y Facultad de Medicina Universidad de Chile) for helping develop the third course of the program; Barbara Raty (physical therapist from Servicio de Kinesiología, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile) for helping develop the third course of the program; Francisco Cruzat and Juan Pablo Ghiringhelli (anesthesiologists from the División de Anestesiología, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile) for helping develop the fourth course of the program; Dalroh Koulyo, Prosper Beotombaye, Pierre Farah and Simon Madengar (doctors from Complexe Hospitalier-Universitaire Le Bon Samaritain) for receiving the Chilean anesthesiologists in their hospital, and allowing them to work in their medical teams; Verónica Mertz, Ana Oliveros and Marcia Corvetto (anesthesiologists from the División de Anestesiología, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile) for helping in the design, approval and funding of the program, and for allowing the use of their simulation mannequins; and Guillermo Lema and Jan Updegraff (anesthesiologists from the División de Anestesiología, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile) for supervising and proofreading the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Hilary P. Grocott, Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia.

Author contributions

Eduardo Kattan and R. López Barreda contributed to all aspects of this manuscript, including study conception and design; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; and drafting the article. Rodrigue Takoudjou contributed to the acquisition of data and to the conception and design of the manuscript. Karen Venegas and Julio Brousse contributed to the acquisition of data. Alejandro Delfino contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data.

Funding

This project was supported with departmental and institutional funds. No other funds were received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kattan, E., Takoudjou, R., Venegas, K. et al. A basic anesthesia training program for nurses in Chad: first steps for a south–south academic cooperation program. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 66, 828–835 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-019-01341-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-019-01341-8