Abstract

Purpose

The incidence of epidural top-ups received in the second stage of labour in nulliparous women and the obstetrical and neonatal implications associated with these boluses are explored in this retrospective observational study. We hypothesized that an epidural top-up in the second stage of labour reduces operative deliveries by resolving inadequate analgesia.

Methods

A population-based cohort analysis was performed using perinatal data from 1 January 2013 through 31 December 2014. An anesthesia database provided information to determine the top-up incidence. Women with or without a top-up for second-stage duration were compared for method of delivery and neonatal characteristics using descriptive statistics. Logistic regression identified predictive factors for method of delivery.

Results

Of the 1,462 women with a second stage of labour > one hour who received epidural analgesia, 105 (7%) required a top-up during the second stage of labour. Women who received a top-up were more likely to have had induction of labour and/or augmentation (89% vs 76%; odds ratio [OR], 2.43; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.32 to 4.49; P = 0.003), a longer second stage (303 min vs 171 min; mean difference, 132 min; 95% CI, 113 to 151; P < 0.001), and more assisted vaginal (41% vs 17%; OR, 3.35; 95% CI, 2.21 to 5.1; P < 0.001) or Cesarean deliveries (26% vs 11%; OR, 3.04; 95% CI, 1.91 to 4.8; P < 0.001) than women without a top-up.

Conclusion

Most women who received a top-up had a vaginal (spontaneous or assisted) delivery. Compared with women without a top-up, women requiring a top-up had more predictors of difficult labour and higher rates of assisted vaginal delivery and Cesarean delivery.

Résumé

Objectif

L’incidence des bolus administrés par voie péridurale au cours de la deuxième phase du travail chez des femmes nullipares et les implications obstétricales et néonatales associées à ces bolus sont explorées dans cette étude observationnelle rétrospective. Nous avons formulé l’hypothèse qu’un bolus par voie péridurale au cours de la deuxième phase du travail diminuerait les manœuvres au cours des accouchements en corrigeant une analgésie inadéquate.

Méthodes

Une analyse de cohorte de population a été réalisée à partir des données périnatales entre le 1er janvier 2013 et le 31 décembre 2014. Une base de données d’anesthésie a fourni l’information nécessaire pour déterminer l’incidence des bolus. La comparaison du mode d’accouchement et des caractéristiques néonatales pour les femmes ayant reçu ou non des bolus au cours de la deuxième phase de travail a été réalisée au moyen de statistiques descriptives. Un modèle de régression logistique a identifié les facteurs prédictifs du mode d’accouchement.

Résultats

Parmi les 1 462 femmes dont la deuxième phase du travail a duré plus d’une heure et qui ont reçu une analgésie péridurale, 105 (7 %) ont nécessité un bolus péridural au cours de cette deuxième phase. Les femmes ayant reçu un bolus ont été plus susceptibles d’avoir un déclenchement et/ou une intensification du travail (89 % contre 76 %; rapport de cotes [OR], 2,43; intervalle de confiance [IC] à 95 % : 1,32 à 4,49; P = 0,003), un allongement de la deuxième phase (303 min contre 171 min; différence des moyennes, 132 min; IC à 95 %, 113 à 151; P < 0,001), et davantage d’accouchements assistés par voie vaginale (41 % contre 17 %; OR, 3,35; IC à 95 %, 2,21 à 5,1; P < 0,001) ou de césariennes (26 % contre 11 %; OR, 3,04; IC à 95 %, 1,91 à 4,8; P < 0,001) par rapport aux femmes n’ayant pas reçu de bolus.

Conclusion

La majorité des femmes ayant reçu un bolus d’analgésie péridurale a accouché par voie vaginale (spontanée ou assistée). Comparativement aux femmes n’ayant pas reçu de bolus, celles qui en ont eu avaient davantage de facteurs prédictifs de travail difficile et des taux plus élevés d’accouchements assistés par voie vaginale et de césariennes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Passive descent of the fetus and the active phase of maternal pushing make up the second stage of labour.1 The duration of active pushing significantly impacts maternal and neonatal outcomes.2,3 For nulliparous women receiving epidural analgesia, a rest period has been advocated at full dilatation to allow the fetus to passively rotate and descend.1 Passive descent allows the woman to delay pushing until she feels the urge or the fetal head is visible at the vaginal introitus. Brancato et al.4 recommend passive descent with effective epidural analgesia to promote better birth outcomes. Additionally, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines state “if the maternal and fetal conditions permit, allow for the following: At least two hours of pushing in multiparous women, at least three hours of pushing in nulliparous women. Longer durations may be appropriate (e.g., with the use of epidural analgesia) if progress is being documented”.5

To ameliorate breakthrough pain, an epidural analgesic intervention commonly referred to as a “top-up” is occasionally provided during the second stage of labour. A top-up is a bolus of local anesthetic, with or without opioid, provided by an anesthesia team member. Epidural analgesia lowers epinephrine concentrations, thus improving uterine contractions and placental perfusion,6 and, if discontinued in the second stage of labour, results in pain and ineffective pushing.7 Indraccolo et al.8 found that increasing the total number of top-ups independently reduced the odds of undergoing Cesarean delivery and decreased the duration of the second stage of labour.

The objectives of this study were to determine the incidence of top-ups in the second stage of labour in women receiving epidural analgesia and to compare obstetrical characteristics and outcomes (length of the second stage, method of delivery, augmentation/induction use) and neonatal characteristics (Apgar score, birth weight) between women who received an epidural top-up in the second stage and those who did not. We hypothesized that resolving inadequate analgesia with a top-up may allow for passive descent of the fetus, avoiding complications associated with early pushing, and thus promote spontaneous vaginal deliveries.

Methods

A population-based cohort analysis was completed using data derived from the Nova Scotia Atlee Perinatal Database (NSAPD) for women who delivered from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2014 at the IWK Health Centre.9 Through data reabstraction (with a high level of agreement for most routine variables) and validation studies, the NSAPD has been shown to contain reliable information.10,11 The study was approved (24 November 2015) by the IWK Health Centre Research Ethics Board (IWK REB 1020702) and written informed consent was waived.

Information on epidural interventions and top-ups was provided by the anesthesia clinical database (Innovian, Draeger, Inc. Telford, PA, USA), a newly implemented information management system. At the time of the data request, complete data was only available for the specified study time period. Anesthetic characteristics collected from Innovian were: type of epidural, time of epidural initiation, epidural initiated in the second stage, repeat epidural in the second stage, number of epidural top-ups, type of epidural top-ups, and time of epidural top-ups in the second stage of labour. Top-ups for labour analgesia were recorded separately within the anesthesia database, differentiating them from those used for assisted vaginal delivery or Cesarean delivery. Only top-ups used to treat inadequate labour analgesia were included in the analysis. Using OB TraceVue (OBTV, Phillips Medical Systems, Koninklijke Philips N.V.) obstetrical care software, peripartum data was collected, which was linked to the NSAPD using structured provincial procedures. Progress in labour was evaluated every two hours once in active labour phase or if otherwise clinically indicated. The length of the second stage of labour was calculated from 10-cm cervical dilatation until delivery and entered into OBTV, in real time, by an obstetrical care nurse. If a top-up occurred in the second stage of labour, the following anesthetic characteristics were collected from OBTV: presence of motor block and highest modified Bromage score.12 These parameters are assessed hourly by birth unit nurses. Complete obstetrical, neonate, and anesthesia characteristics and outcomes are listed in the Appendix (available as Electronic Supplementary Material).

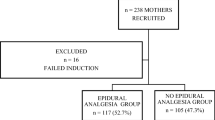

Women were included in the study if they were nulliparous, at term gestation (≥ 37 weeks), labouring with a singleton pregnancy in vertex presentation, and received epidural analgesia. Women were only included if they had a second stage of labour > one hour to allow for passive descent of the fetus and to exclude women who may have delivered precipitously. Women with hypertensive disease or diabetes in pregnancy were excluded because they can be at increased risk for complicated deliveries.13,14

Labour analgesia was initiated using either a combined spinal epidural (CSE) technique (1 mL of 2 mg bupivacaine 0.25% with 10 µg·mL−1 fentanyl) or a standard epidural bolus (10 mL of 0.1% ropivacaine with 10 µg·mL−1 fentanyl) at the attending anesthesiologist’s discretion. Labour analgesia was maintained with ropivacaine 0.1% and fentanyl 2 µg·mL−1 at 6 mL·hr−1 and the option of patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA). Patient-controlled epidural analgesia provided an additional 6 mL of the same epidural solution every ten minutes as required. The infusion continued until the patient was moved to the operating room or completion of the third stage of labour and, if needed, perineal repair. If the labour epidural was initiated in the second stage of labour, it was considered a top-up. If the pain was not controlled after three successful PCEA deliveries, or sensory block was considered inadequate, patchy, or unilateral, then the labour nurse could request an anesthesia assessment for the patient and the anesthesia team member could provide a top-up as required. Although not recorded, it was assumed that three successful consecutive PCEA boluses were provided before a top-up was requested, as per institutional policy. The top-up was a 10-mL syringe of ropivacaine 0.2% with or without fentanyl 10 µg·mL−1 (two separate preparations) at the anesthesia provider’s discretion. The specific volume administered was not always recorded in the anesthetic record but institutional practice is to deliver the 10-mL volume provided in prefilled syringes by the pharmacy.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics including mean (standard deviation [SD]) and median (interquartile range [IQR]), and sample size and percentages were calculated and used to identify the population characteristics. Maternal characteristics were analyzed categorically using the Chi-square test to address whether certain characteristics were influenced by top-ups. Some of these characteristics included smoking status, pre-pregnancy weight (kg), education level, race/ethnicity, and Quintile of Annual Income per Person Equivalent (QAIPPE) Score.15 Length of the second stage of labour and duration of the epidural were analyzed via a Student’s t test. Induction and augmentation of labour, analgesia induction with CSE, method of delivery, and need for episiotomy were calculated using the Chi-square test. Neonatal resuscitation was a grouped variable that included oxygen administration, continuous positive airway pressure use, naloxone use, epinephrine use, and chest compressions and was compared using the Chi-square test. Apgar scores were analyzed using the Chi-square test, while neonatal weight, cord artery pH, cord artery partial pressure of carbon dioxide, and cord artery base excess were analyzed using Student’s t test.

Variables were selected for the multivariate logistic regression model based on univariable analysis indicating a P < 0.1 significance for method of delivery. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed in a backward stepwise fashion (factor retained if it changed the point estimate of the variable representing method of delivery by 5% or more) to generate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) to determine predictive factors (maternal age, neonatal birth weight, augmentation, nitrous oxide use, smoking, and top-up) for method of delivery. SPSS Statistic 21 software package was used to analyze all data (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Of the 1,462 women with a second stage of labour > one hour who received epidural analgesia, 105 (7%) required a top-up during the second stage of labour (Table 1). Epidural analgesia was initiated with an epidural bolus for 1,024 (70%) women and with CSE for 438 (30%) women (Table 1). The labour epidural was initiated in the second stage of labour in 20 women (1.4%) and was included in the top-up group for analysis. Eleven women (0.8%) received a CSE, while nine (0.6%) had an epidural bolus initiation of labour analgesia in the second stage of labour. Seven women (0.5%) required a repeat epidural in their second stage and were excluded from analysis.

There were no significant differences in demographics between women who received a top-up and those who did not, with the exception of race. Fifty-nine women (89%) who received a top-up were Caucasian, whereas 645 Caucasian women (78%) did not receive a top-up (P = 0.03; Table 2). There were no significant differences in neonatal characteristics for the group of women who received a top-up, with the exception of birth weight; neonates born to those women who required a top-up had a higher birth weight (3641 g vs 3459 g; Table 2).

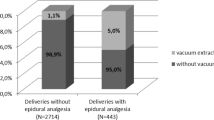

Women requiring a top-up in the second stage of labour were more likely to have an induction and/or medical augmentation of labour than women who did not require a top-up (Table 2). Women who received a top-up in the second stage of labour were more likely to have had a Cesarean delivery than women who did not have a top-up (26% vs 11%, Table 3). Also, women who received a top-up in the second stage of labour were more likely to require an assisted vaginal delivery than those who did not receive a top-up (41% vs 17%, Table 3). Logistic regression identified maternal age, birth weight, induction or augmentation of labour, and top-up used as predictors of assisted vaginal delivery and Cesarean delivery (Table 4). Dystocia and fetal distress were the most common indications for Cesarean delivery for both groups (48% and 25%, respectively). Overall, forceps were used in 12% of women, while vacuum extraction was required for 7%.

The length of the second stage was significantly longer for women who received a top-up compared with the group who did not (303 min vs 171 min, respectively; mean difference (MD), 132 min; 95% CI, 113 to 151; P < 0.001; Fig. 1). Women who received a top-up and had a Cesarean delivery had a significantly longer second stage than those who had a top-up and delivered vaginally (349 min vs 287 min, respectively; MD, 62 min; 95% CI, 17 to 107; P = 0.007). Twenty-one women received a top-up within 60 min of the second stage of labour and 84 received a top-up after the first 60 min of the second stage. Women who received a top-up within the first 60 min of the second stage of labour had a shorter second stage than those who received their top-up later (223 min vs 323 min, respectively; MD, 100 min; 95% CI, 53 to 148; P < 0.001; Fig. 2).

Additionally, those women who received their top-up within the first 60 min were more likely to have a spontaneous vaginal delivery than those who received their top-up after the first 60 min of the second stage (62% vs 25%, respectively; OR, 4.88; 95% CI, 1.78 to 13.4; P < 0.001). Compared with women who did not receive a top-up, women who received a top-up within the first 60 min of the second stage of labour had a longer second stage length (171 min vs 223 min, respectively; MD, 52 min; 95% CI, 10 to 93; P = 0.01) but were not more likely to have an assisted vaginal or Cesarean delivery. After 60 min in the second stage of labour, women who received a top-up had a longer second stage (171 min vs 323 min; MD, 152 min; 95% CI, 131 to 173; P < 0.001) and were more likely to have an assisted vaginal or Cesarean delivery than women who did not receive a top-up.

Discussion

This study identified that epidural top-ups occur infrequently during the second stage of labour. Additionally, it found that women requiring a top-up in the second stage of labour had more predictors of difficult labour and a higher rate of assisted vaginal deliveries and operative deliveries than women without a top-up. Women who received a top-up after 60 min in the second stage of labour had longer second stages and more operative deliveries than women who received a top-up within 60 min of the second stage of labour.

While the study finding contrasts our original hypothesis, and that of Indraccolo et al.,8 it implies that top-ups may be a surrogate marker for dystocia. Women experiencing dysfunctional labour have increased analgesic requirements and fewer spontaneous vaginal deliveries.16 Risk factors for dystocia include nulliparity, macrosomia, and hypocontractile uterine activity.17 In the current study, the need for augmentation of labour and increased neonatal birth weight were significantly different for the cohort of women that required a top-up. Similarly, Hess et al.16 examined the relationship between labour outcome and dystocia, defined by the number of top-ups required. They rationalized that epidural top-ups are required for dysfunctional labour and these women are subsequently at a higher likelihood of requiring a Cesarean delivery.16 The relationship between the need for top-up and delivery outcome therefore remains unclear. Due to the retrospective nature of the current study, it is difficult to determine if the top-up necessitated an operative delivery or if the top-up was required for inadequate analgesia due to dystocia.

Dystocia, rather than a local anesthetic bolus, seems more likely responsible for the increased assisted vaginal and Cesarean deliveries noted in this study. Previously, labour epidural analgesia was associated with higher rates of assisted vaginal deliveries, longer second stages of labour, and possibly higher Cesarean delivery rates.18,19,20,21 High concentrations of local anesthetic may reduce oxytocin release by affecting pelvic autonomic nerves, increasing the chance of assisted vaginal delivery.22 These earlier trials do not reflect the lower concentration of local anesthetics used in contemporary practice and in the current study. Anim-Somuah et al.23 showed that epidural analgesia does not increase the risk of operative delivery, and this result has been supported in recent meta-analyses evaluating low-concentration epidural analgesia.24,25 Low concentrations of local anesthetics reduce assisted vaginal deliveries and shorten the second stage of labour compared with high-concentration formulations.24,25 In the absence of routinely collected information on sensory levels and Bromage scores before and after top-up, the association between increased local anesthetic from the top-up and method of delivery remains unclear. Nevertheless, current literature examining low-dose local anesthetic solutions makes the implication that top-ups were responsible for increased operative deliveries less plausible.

The average length of the second stage of labour in this cohort was 181 min, consistent with current guidelines.6 With clinical trends toward longer second stages of labour, obstetrical care providers may be reassured that providing an epidural top-up does not preclude vaginal delivery. This study showed that among women who receive a top-up, the majority of women had spontaneous or assisted vaginal delivery. Adequate analgesia with a top-up bolus may allow for a longer second stage of labour with subsequent vaginal delivery. Women who received a top-up and had a Cesarean delivery had a significantly longer second stage, although interpretation of this finding is complicated by the time from the decision to perform a Cesarean delivery to beginning it, which included operating room preparation, patient transport, and mobilization of staff resources.

The timing of the top-up during the second stage may affect delivery outcomes. Indraccolo et al.8 noted that increased time from the first dose of epidural to the last top-up raised the risk of operative delivery and the duration of the second stage of labour. The current study showed that women who were provided a top-up within the first 60 min of the second stage of labour had a shorter overall second stage and were more likely to have a spontaneous vaginal delivery. Women requiring a top-up after 60 min of the second stage may represent an alternate population. For the subset of women who had a longer second stage of labour, providing a top-up may represent a surrogate marker for dystocia, which increases the operative delivery risk.

The incidence of top-ups that occur in nulliparous women with epidural analgesia in the second stage of labour was 7%. This is important as it may help anesthesia providers predict and plan for breakthrough pain requiring clinician-administered rescue boluses. Overall, women with or without a top-up were not different in terms of demographics, with the exception of race. Nova Scotia has a relatively homogeneous, predominantly Caucasian population.26 In this study, Caucasian women comprised 79% of the population and were more likely to have received a top-up. Racial and ethnic disparities in the management of pain have been well established.27,28,29 Labour epidural rates tend to be lower for African American, Hispanic, and Asian women than for Caucasian non-Hispanic women.29

The current study has a number of limitations. While NSAPD data have been shown to contain reliable information,10,11 retrospective studies are limited to available data, and there may be other variables relevant to the present study that were not routinely captured. In addition, Nova Scotia’s population characteristics may have limited generalizability in more ethnically or racially diverse populations.

This study was not able to distinguish passive and active phases of the second stage of labour; top-ups given early (during the passive phase) may promote a spontaneous delivery. Progress in labour is evaluated every two hours once in active labour or if otherwise clinically indicated; thus, identification of the start of the second stage and the first 60 min of the second stage may not be clearly delineated. Information on the duration of the second stage, defined as the start of the second stage of labour until delivery, necessarily included the length of time from decision for operative delivery to delivery (including awaiting room set-up and team availability). The current study was not able to distinguish whether assisted vaginal delivery was due to obstetric indications or medical reasons (such as cardiac conditions); medical indications make up a very small percentage of the general population and their influence should be small. With Bromage scores completed in less than half of the study population, uncharted sensory examinations, and a study population with risk factors for dystocia, the true association between top-up and delivery type may be less accurate. Finally, whether the top-up implies dystocia or inadequate epidural placement is not known. Although need for multiple top-ups could help identify whether or not the epidural was working appropriately, these cases were not specifically analyzed.

In summary, top-ups occur with a frequency of 7% during the second stage of labour. Future studies should evaluate the timing of top-ups in relation to the second stage, as early interventions may facilitate a spontaneous vaginal delivery. Evaluation of the indication for top-ups (inadequate analgesia, augmentation, dystocia) in the second stage would help determine a true association between the intervention and delivery outcome. With new interest in prolonging the length of the second stage to achieve spontaneous vaginal deliveries, a prospective study examining the timing of when the top-up is provided and delivery outcome would better predict the effects of the intervention.

References

Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 687: approaches to limit intervention during labor and birth. Obstet Gynecol 2017; 129: e20-8.

Rouse DJ, Weiner SJ, Bloom SL, et al. Second-stage labor duration in nulliparous women: relationship to maternal and perinatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009; 201: 357.e1-7.

Le Ray C, Audibert F, Goffinet F, Fraser W. When to stop pushing: effects of duration of second-stage expulsion efforts on maternal and neonatal outcomes in nulliparous women with epidural analgesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009; 201: 361.e1-7.

Brancato RM, Church S, Stone PW. A meta-analysis of passive descent versus immediate pushing in nulliparous women with epidural analgesia in the second stage of labor. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2008; 37: 4-12.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (College); Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Caughey AB, Cahill AG, Guise JM, Rouse DJ. Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014; 210: 179-93.

Lee L, Dy J, Azzam H. Management of spontaneous labour at term in healthy women. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2016; 38: 843-65.

Torvaldsen S, Roberts CL, Bell JC, Raynes-Greenow CH. Discontinuation of epidural analgesia late in labour for reducing the adverse delivery outcomes associated with epidural analgesia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004: Cd004457.

Indraccolo U, Ripanelli A, Di Iorio R, Indraccolo SR. Effect of epidural analgesia on labor times and mode of delivery: a prospective study. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 2012; 39: 310-3.

Dodds L, Allen A, Kuhle S, Woolcott C. Nova Scotia Atlee Perinatal Database Report of Indicators - December 2015. Available from URL; http://rcp.nshealth.ca/sites/default/files/publications/nsapd_indicator_report_2005_2014.pdf.

Fair M, Cyr M, Allen AC, Wen SW, Guyon G, MacDonald RC. An assessment of the validity of a computer system for probabilistic record linkage of birth and infant death records in Canada. The Fetal and Infant Health Study Group. Chronic Dis Can 2000; 21: 8-13.

Joseph KS, Fahey J. Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. Validation of perinatal data in the discharge abstract database of the Canadian Institure for Health Information. Chronic Dis Can 2009; 29: 96-100.

Breen TW, Shapiro T, Glass B, Foster-Payne D, Oriol NE. Epidural anesthesia for labor in an ambulatory patient. Anesth Analg 1993; 77: 919-24.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2013; 122: 1122-31.

HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group; Metzger BE, Lowe LP, et al. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1991-2002.

Wilkins R, Khan S. Automated Geographic Coding Based on the Statistics Canada Postal Code Conversion Files. January 2011. Available from URL: https://mdl.library.utoronto.ca/sites/default/files/mdldata/open/canada/national/statcan/postalcodes/pccfplus/2006/2010oct/MSWORD.PCCF5H.pdf (accessed May 2018).

Hess PE, Pratt SD, Soni AK, Sarna MC, Oriol NE. An association between severe labor pain and cesarean delivery. Anesth Analg 2000; 90: 881-6.

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 49, December 2003: Dystocia and augmentation of labor. Obstet Gynecol 2003; 102: 1445-54.

Neuhoff D, Burke MS, Porreco RP. Cesarean birth for failed progress in labor. Obstet Gynecol 1989; 73: 915-20.

Thorp JA, Eckert LO, Ang MS, Johnston DA, Peaceman AM, Parisi VM. Epidural analgesia and cesarean section for dystocia: risk factors in nulliparas. Am J Perinatol 1991; 8: 402-10.

Thorp JA, Parisi VM, Boylan PC, Johnston DA. The effect of continuous epidural analgesia on cesarean section for dystocia in nulliparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989; 161: 670-5.

Hess PE, Pratt SD, Lucas TP, et al. Predictors of breakthrough pain during labor epidural analgesia. Anesth Analg 2001; 93: 414-8.

Bates RG, Helm CW, Duncan A, Edmonds DK. Uterine activity in the second stage of labour and the effect of epidural analgesia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1985; 92: 1246-50.

Anim-Somuah M, Smyth RM, Jones L. Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011: 12: CD000331.

Sultan P, Murphy C, Halpern S, Carvalho B. The effect of low concentrations versus high concentrations of local anesthetics for labour analgesia on obstetric and anesthetic outcomes: a meta-analysis. Can J Anesth 2013; 60: 840-54.

Wang TT, Sun S, Huang SQ. Effects of epidural labor analgesia with low concentrations of local anesthetics on obstetric outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesth Analg 2017; 124: 1571-80.

Statistics Canada. 2006 Community Profiles. Available from URL: http://www12.statcan.ca/census-recensement/2006/dp-pd/index-eng.cfm.

Chen EH, Shofer FS, Dean AJ, et al. Gender disparity in analgesic treatment of emergency department patients with acute abdominal pain. Acad Emerg Med 2008; 15: 414-8.

Pletcher MJ, Kertesz SG, Kohn MA, Gonzales R. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. JAMA 2008; 299: 70-8.

Rust G, Nembhard WN, Nichols M, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the provision of epidural analgesia to Georgia Medicaid beneficiaries during labor and delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004; 191: 456-62.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Munro, A., George, R.B. & Allen, V.M. The impact of analgesic intervention during the second stage of labour: a retrospective cohort study. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 65, 1240–1247 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-018-1184-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-018-1184-1