Abstract

Purpose

Investigation of adverse events associated with anesthetic procedures is a method of quality control that identifies topics to improve clinical care and patient safety. Most research to date has been based on closed claim registries and anonymous reports which have specific limitations. Therefore, to evaluate a hospital’s reporting system, the present study was designed to describe critical incidents that anesthesiologists voluntarily and non-anonymously reported through an anesthesia information management system.

Methods

This is a historical observational cohort study on patients (age > 18 yr) undergoing anesthetic procedures in a tertiary referral hospital. A 20-item list of complications, as developed by the Netherlands Society of Anesthesiologists, was prospectively completed for each procedure. All critical incidents registered in the anesthesia information management system were then reclassified into 95 different critical incidents in a reproducible way.

Results

There were 110,310 procedures performed in 65,985 patients, and after excluding 158 reports that did not depict a critical incident, 3,904 critical incidents in 3,807 (3.5%) anesthetic procedures remained. Technical difficulties with regional anesthesia (n = 445; 40 per 10,000 anesthetics; 95% confidence interval [CI], 36 to 44), hypotension (n = 432; 39 per 10,000 anesthetics; 95% CI, 35 to 43), and unexpected difficult intubation (n = 216; 20 per 10,000 anesthetics; 95% CI, 18 to 23) were the most frequently documented critical incidents.

Conclusion

Accurate measurement and monitoring of critical incidents is crucial for patient safety. Despite the risk of underreporting and probable misclassification of manual reporting systems, our results give a comprehensive overview on the occurrence of voluntarily reported anesthesia-related critical incidents. This overview can direct development of a new reporting system and preventive strategies to decrease the future occurrence of critical incidents.

Résumé

Objectif

Les enquêtes portant sur les complications associées aux interventions anesthésiques sont une méthode de contrôle de la qualité qui identifie les domaines où les soins cliniques et la sécurité des patients peuvent être améliorés. La plupart des recherches se sont jusqu’ici basées sur les registres des plaintes réglées et les comptes rendus anonymes, ce qui entraîne certaines limites spécifiques. Par conséquent, afin d’évaluer le système de déclaration des incidents d’un hôpital, notre étude a été conçue de façon à décrire les incidents critiques que les anesthésiologistes ont rapporté de façon volontaire et non anonyme via un système de gestion de l’information en anesthésie.

Méthode

Il s’agit d’une étude de cohorte observationnelle historique portant sur des patients (âgés de plus de 18 ans) subissant des interventions anesthésiques dans un hôpital central de soins tertiaires. Une liste de complications comprenant 20 éléments, telle que mise au point par la Société néerlandaise des anesthésiologistes, a été complétée de façon prospective lors de chaque intervention. Tous les incidents critiques enregistrés dans le système de gestion de l’information en anesthésie ont ensuite été reclassés en 92 incidents critiques différents d’une manière reproductible.

Résultats

Au total, 110 310 interventions ont été réalisées chez 65 985 patients, et après avoir exclus 158 comptes rendus qui ne décrivaient pas d’incident critique, il restait 3904 incidents critiques dans le cadre de 3807 (3,5 %) interventions anesthésiques. Les difficultés techniques liées à l’anesthésie régionale (n = 445; 40 par 10 000 anesthésies; intervalle de confiance [IC] 95 %, 36 à 44), l’hypotension (n = 432; 39 par 10 000 anesthésies; IC 95 %, 35 à 43), et les intubations difficiles non anticipées (n = 216; 20 par 10 000 anesthésies; IC 95 %, 18 à 23) constituaient les incidents critiques les plus fréquemment documentés.

Conclusion

La mesure précise et la surveillance des incidents critiques sont essentielles à la sécurité des patients. Malgré le risque de sous-documentation et de mauvaise classification probable des systèmes de déclaration manuels, nos résultats donnent une vue d’ensemble complète concernant la survenue d’incidents critiques liés à l’anesthésie et rapportés de façon volontaire. Cette vue d’ensemble peut guider la mise au point d’un nouveau système de déclaration des incidents et de stratégies de prévention afin de réduire la survenue future d’incidents critiques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Monitoring and reporting critical incidents, such as hypotension or a state of awareness, can indicate the quality of clinical practice. Therefore, reporting medical complications voluntarily is encouraged by the World Health Organization and the Dutch Health Care Inspectorate.1,2 Registration of critical incidents not only provides an assessment of the quality of practice but also offers knowledge of the most frequent and most severe critical incidents.

Anesthesiologists should share their experiences with critical incidents in order to increase their knowledge of the potential risks and identify patterns in the development of critical incidents. The gaps and inadequacies found in the healthcare system can be optimized to improve patient safety.3-9 Furthermore, evaluation and feedback constantly encourage clinicians to report critical incidents.3,10

Many countries have developed systems to investigate the number and severity of these critical incidents.7,11-20 Most research has been based on closed claim analysis or anonymous reporting systems; however, these methods have limitations. For example, closed claim analyses will not contain all complications, only those that involve patients and are deemed important. Therefore, in order to evaluate a hospital reporting system and identify topics to improve clinical care and patient safety, we designed the present study to describe critical incidents that anesthesiologists reported voluntarily and non-anonymously through an anesthesia information management system (AIMS) in a tertiary referral hospital.

Methods

Study design

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University Medical Center Utrecht reviewed the study protocol and found that it was not subject to the Dutch Medical Research in Human Subjects Act. Therefore, the IRB waived the need for informed consent (11-271/C; July 5, 2011). This observational study describes prospectively reported critical incidents and complications relating to anesthesia in patients 18 years and older undergoing any type of anesthetic procedure in a tertiary referral university hospital (University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands) from January 1, 2005 to May 18, 2011. Anesthesiologists and anesthesia registrars voluntarily reported complications and critical incidents on a non-anonymous basis via the 20-item complication list of the Netherlands Society of Anesthesiologists. The reporting system was implemented in September 2004; therefore, we chose to evaluate critical incidents reported as of January 1, 2005 to allow an optimization period of three months.

Definitions

We defined a critical incident as an event that could have led (if not discovered or corrected in time) or did lead to an undesirable outcome, i.e., ranging from increased length of hospital stay to death or permanent disability. We included all anesthesia-related critical incidents that occurred at a time when the patient was under the care of an anesthesiologist and were described in clear detail by a person who either observed or was involved in the critical incident. We included critical incidents that not only seemed preventable (i.e., inadequate preoperative screening) or involved human error (i.e., medication error)21 but also were non-preventable (i.e., unexpected difficult intubation).3,15,22

Data acquisition

Critical incidents were reported by anesthesiologists and anesthesia registrars (reporters) in the AIMS on a voluntary and non-anonymous basis. During every anesthetic procedure, a menu item in the AIMS termed complication is presented by pressing the standard event key 〈start skin closure〉, at which time, a reporter can complete a standardized computerized audit form. If a critical incident is reported, a drop down menu displays the 20-item complication list (with miscellaneous as an additional option) developed by the Netherlands Society of Anesthesiologists (Table 1). Thereafter, the incident’s grade of severity can be reported and, if deemed necessary, free text can be added. If the complication report is not entered into the database by the end of the day, the anesthesiologist involved receives a reminder e-mail. Upon completion, the critical incident report is stored in a database within the AIMS along with the patient characteristics. The registry also includes a means to assign a pop-up warning for subsequent anesthetic procedures (i.e., difficult intubation).

The currently used 20-item complication list of the Netherlands Society of Anesthesiologists facilitates a generalized classification of critical incidents. After reviewing the critical incident reports, we concluded that we could not base firm conclusions on the classification system as it was too generalized; therefore, we reclassified all critical incidents. Based on the initial classification and comments added by the reporter, we reclassified the critical incidents in keeping with a classification system of the German Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care13 which is a more detailed classification system on which to base our conclusions. If no comment was available or the comment was unclear, we consulted the AIMS to investigate the critical incident in detail. One researcher (K.M.) reviewed all critical incidents. When information was inconsistent, consensus was reached by discussion with two researchers (J.d.G. and B.v.Z.). If more than one category was possible for one critical incident, the most appropriate or most severe category was chosen. If different critical incidents occurred during one anesthetic procedure, these were categorized as separate critical incidents. All reports involving death as grade of severity were discussed with all observers (K.M., J.d.G., and B.v.Z.).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® 17.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), except for the calculation of the 95% confidence interval (CI) according to Wilson’s formula (EpiTools: http://epitools.ausvet.com.au). Procedures with more than one critical incident were counted once. Where appropriate, a Chi square test or an independent samples Student’s t test was carried out to display differences between groups. All reported P values are two sided.

Results

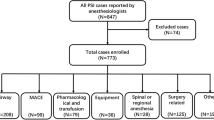

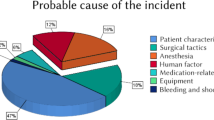

The complication status of 104,133 (94.4%) of 110,310 anesthetic procedures was known (95% CI, 94.2 to 94.5) (Figure). In total, 4,062 events were reported in the AIMS, and 158 (3.9%) reports were classified as not being a critical incident (95% CI, 3.3 to 4.5) because they consisted of surgical complications and warnings for a subsequent anesthetic procedure. The remaining 3,904 critical incidents were found in 3,807 of the 110,310 anesthetic procedures (354 per 10,000 anesthetics; 95% CI, 343 to 365). The 3,904 critical incidents consisted of one single critical incident in 3,715 (97.6%) anesthetic procedures, two critical incidents in 87 (2.3%) anesthetic procedures, and three critical incidents in five (0.1%) anesthetic procedures. Table 2 shows demographic data of the study population; no clinically significant differences were found. The largest critical incident categories were cardiovascular incidents, with 1,164 incidents (106 per 10,000 anesthetics), respiratory problems with 851 incidents (77 per 10,000 anesthetics), and lesions with 820 incidents (74 per 10,000 anesthetics) (Table 3). The cardiovascular critical incidents consisted mainly of hypotension; the respiratory problems critical incidents consisted mainly of difficulties to ventilate (with or without hypoxemia), difficulties to intubate, bronchospasm, and laryngospasm; and the lesion critical incidents consisted mainly of technical difficulties with regional anesthesia (Table 4). The largest groups of reported critical incidents were technical difficulties with regional anesthesia (40 per 10,000 anesthetics) and hypotension (39 per 10,000 anesthetics) (Table 5).

Critical incidents with (probable) permanent damage consisted primarily of respiratory and cardiovascular critical incidents. Forty-three (1.1% of all critical incidents) critical incidents led to the death of a patient receiving an anesthetic procedure; forty of those critical incidents comprised a cardiovascular incident ranging from arrhythmia to myocardial infarction (Table 6).

Discussion

The voluntary and non-anonymous critical incident registration system in this study proved to be very effective (response rate 94.4%). This high response was achieved by way of a reminder in the AIMS for reporting during skin closure and an e-mail reminder after completion of the anesthetic procedure. Furthermore, the non-anonymous registration allowed feedback through a twice weekly complication meeting in which action regarding a critical incident was discussed and initiated, thereby encouraging clinicians to report critical incidents. In 3.5% (354 per 10,000 anesthetics; 95% CI, 343 to 365) of anesthetic procedures a critical incident was reported, which is similar to the incidence reported in children using the same methodology.23

The present voluntary and non-anonymous reporting system is unique and has its advantages and disadvantages. Voluntarily reported critical incidents may suffer from underreporting.3,24 Previous studies have shown a low level of compliance when voluntary reporting was compared with automatically detected critical incidents,25-27 and in a different study, an incidence of 28% was reached when researchers completed a retrospective evaluation of all anesthetic procedures.13 Nevertheless, the response rate in the present system was very high (94%), and the advantage of the present system is the fact that anesthesiologists reported only those critical incidents considered to be clinically relevant. The non-anonymous system of reporting may also cause underreporting because a reporter might refrain from reporting due to fear of consequences.6,10,24 Nevertheless, a strong advantage of non-anonymous reporting is the ability to discuss the critical incident with detailed information from the involved anesthesiologist, which can lead to a teaching moment.3

The reporting system used in this study was based on the 20-item complication list of the Netherlands Society of Anesthesiologists. This 20-item complication list was not sufficient for detailed analysis and required extension as 21.6% of reported events could not be classified within the original list and were reported as miscellaneous (Tables 1 and 4). Nevertheless, the limited number of items in the classification system of the Netherlands Society of Anesthesiologists and the large amount of critical incidents in the miscellaneous category might have induced underreporting of the items not in the original list. For example, some might judge certain events as a critical incident, while others might judge the same event as not being a critical incident, and vice versa.24,28 It could be argued that not every critical incident that we present is truly a critical incident, e.g., technical difficulties with regional anesthesia are an inevitable occurrence when performing regional anesthesia. Furthermore, for the present study, all critical incidents were reclassified retrospectively to allow detailed analyses, and lack of information may have caused misclassification.

Cardiovascular incidents (106 per 10,000 anesthetics), in particular hypotension (40 per 10,000 anesthetics), comprised the majority of critical incidents (Tables 3 and 5). Previous studies showed the same level of cardiovascular incidents,13,29 whereas some studies indicated that difficulty with airway management 11,14,16,29,30 or wrong drug/wrong drug-dose/wrong drug-labelling 14 was the critical incident that occurred most frequently. This variance in number and type of critical incident might be due to the diversity of methods in the reporting systems and differences in definitions. For example, closed claims studies report death (26%), nerve injuries (22%), and permanent brain damage (9%) as the most common complications.11

The present study identified the most frequently reported and most severe anesthetic critical incidents in our hospital on which to base future improvements for patient safety. The technical difficulties with regional anesthesia (Table 5) are being addressed in part by implementation of ultrasound guidance,31 but we propose a thorough investigation to determine which regional technique results in the most technical difficulties. Furthermore, the administration of the wrong drug (Table 4) is being tackled by strictly double-checking medication before administration.32

In conclusion, the present study shows that the present reporting system in AIMS along with e-mail feedback leads to a very high response rate in reporting critical incidents. Even so, the complication lists of the Netherlands Society of Anesthesiologists proved to be too limited, and therefore, the present list of complications can be used as an alternative. Cardiovascular complications were reported most frequently.

References

The Health Care Inspectorate. Basic set of quality indicators for hospitals 2012 (Dutch). Available from URL: http://www.igz.nl/zoeken/document.aspx?doc=Basisset+kwaliteitsindicatoren+ziekenhuizen+2012&docid=3620 (accessed July 2015).

World Health Organization. World Alliance for Patient Safety. WHO Draft Guidelines for Adverse Event Reporting and Learning Systems. Switzerland: WHO Press; 2005. Available from URL: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/events/05/Reporting_Guidelines.pdf (accessed July 2015).

Staender S, Kaufmann M, Scheidegger D. Critical incident reporting. with a view on approaches in anaesthesiology. In: Safety in Medicine. Amsterdam New York: Pergamon Elsevier Science; 2000: 65-82.

Staender S, Schaer H, Clergue F, et al. A Swiss anaesthesiology closed claims analysis: report of events in the years 1987-2008. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2011; 28: 85-91.

Whitaker DK, Brattebo G, Smith AF, Staender SE. The Helsinki Declaration on patient safety in anaesthesiology: putting words into practice. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2011; 25: 277-90.

Vincent C, Taylor-Adams S, Stanhope N. Framework for analysing risk and safety in clinical medicine. BMJ 1998; 316: 1154-7.

Hubler M, Mollemann A, Metzler H, Koch T. Adverse events and adverse event reporting systems (German). Anaesthesist 2007; 56(1067-8): 1070-2.

Choy CY. Critical incident monitoring in anaesthesia. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2008; 21: 183-6.

Cooper JB. Towards patient safety in anaesthesia. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1994; 23: 552-7.

Mahajan RP. Critical incident reporting and learning. Br J Anaesth 2010; 105: 69-75.

Metzner J, Posner KL, Lam MS, Domino KB. Closed claims’ analysis. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2011; 25: 263-76.

Banks IC, Tackley RM. A standard set of terms for critical incident recording? Br J Anaesth 1994; 73: 703-8.

Schwilk B, Muche R, Treiber H, Brinkmann A, Georgieff M, Bothner U. A cross-validated multifactorial index of perioperative risks in adults undergoing anaesthesia for non-cardiac surgery. Analysis of perioperative events in 26907 anaesthetic procedures. J Clin Monit Comput 1998; 14: 283-94.

Staender S, Davies J, Helmreich B, Sexton B, Kaufmann M. The anaesthesia critical incident reporting system: an experience based database. Int J Med Inform 1997; 47: 87-90.

Webb RK, Currie M, Morgan CA, et al. The Australian Incident Monitoring Study: an analysis of 2000 incident reports. Anaesth Intensive Care 1993; 21: 520-8.

Gupta S, Naithani U, Brajesh SK, Pathania VS, Gupta A. Critical incident reporting in anaesthesia: a prospective internal audit. Indian J Anaesth 2009; 53: 425-33.

Fasting S, Gisvold SE. Data recording of problems during anaesthesia: presentation of a well-functioning and simple system. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1996; 40: 1173-83.

Short TG, O’Regan A, Jayasuriya JP, Rowbottom M, Buckley TA, Oh TE. Improvements in anaesthetic care resulting from a critical incident reporting programme. Anaesthesia 1996; 51: 615-21.

Madzimbamuto FD, Chiware R. A critical incident reporting system in anaesthesia. Cent Afr J Med 2001; 47: 243-7.

Kawashima Y, Seo N, Tsuzaki K, et al. Annual study of anesthesia-related mortality and morbidity in the year 2001 in Japan: the outlines-report of Japanese Society of Anesthesiologists Committee on Operating Room Safety (Japanese). Masui 2003; 52: 666-82.

Cooper JB, Newbower RS, Long CD, McPeek B. Preventable anesthesia mishaps: a study of human factors. Anesthesiology 1978; 49: 399-406.

Morgan C. Incident reporting in anaesthesia. Anaesth Intensive Care 1988; 16: 98-100.

de Graaff JC, Sarfo MC, van Wolfswinkel L, van der Werff DB, Schouten AN. Anesthesia-related critical incidents in the perioperative period in children; a proposal for an anesthesia-related reporting system for critical incidence in children. Paediatr Anaesth 2015; 25: 621-9.

Staender S. Incident reporting in anaesthesiology. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2011; 25: 207-14.

Benson M, Junger A, Fuchs C, et al. Using an anesthesia information management system to prove a deficit in voluntary reporting of adverse events in a quality assurance program. J Clin Monit Comput 2000; 16: 211-7.

Sanborn KV, Castro J, Kuroda M, Thys DM. Detection of intraoperative incidents by electronic scanning of computerized anesthesia records. Comparison with voluntary reporting. Anesthesiology 1996; 85: 977-87.

Simpao AF, Pruitt EY, Cook-Sather SD, Gurnaney HG, Rehman MA. The reliability of manual reporting of clinical events in an anesthesia information management system (AIMS). J Clin Monit Comput 2012; 26: 437-9.

Stanhope N, Crowley-Murphy M, Vincent C, O’Connor AM, Taylor-Adams SE. An evaluation of adverse incident reporting. J Eval Clin Pract 1999; 5: 5-12.

Freestone L, Bolsin SN, Colson M, Patrick A, Creati B. Voluntary incident reporting by anaesthetic trainees in an Australian hospital. Int J Qual Health Care 2006; 18: 452-7.

Hubler M, Mollemann A, Eberlein-Gonska M, Regner M, Koch T. Anonymous critical incident reporting system in anaesthesiology. Results after 18 months (German). Anaesthesist 2006; 55: 133-41.

Schnabel A, Meyer-Frieβem CH, Zahn PK, Pogatzki-Zahn EM. Ultrasound compared with nerve stimulation guidance for peripheral nerve catheter placement: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Anaesth 2013; 111: 564-72.

Meyer-Massetti C, Conen D. Assessment, frequency, causes, and prevention of medication errors - a critical analysis (German). Ther Umsch 2012; 69: 347-52.

Funding

Department only.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is accompanied by an editorial. Please see Can J Anesth 2015; 62: this issue.

Author contributions

Karin E. Munting, Bas van Zaane, Antonius N. J. Schouten, and Jurgen C. de Graaff made a substantial contribution to the conception of the study. Karin E. Munting, Bas van Zaane, and Jurgen C. de Graaff made a substantial contribution to the design of the study and performed the data analysis. Karin E. Munting and Leo van Wolfswinkel made a substantial contribution to the acquisition of data. Karin E. Munting, Bas van Zaane, and Leo van Wolfswinkel made a substantial contribution to the interpretation of the data. Karin E. Munting drafted the article and Bas van Zaane was also involved in drafting the article. Karin E. Munting performed the statistical analysis. Bas van Zaane, Antonius N. J. Schouten, Leo van Wolfswinkel, and Jurgen C. de Graaff revised the article critically for important intellectual content.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Munting, K.E., van Zaane, B., Schouten, A.N.J. et al. Reporting critical incidents in a tertiary hospital: a historical cohort study of 110,310 procedures. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 62, 1248–1258 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-015-0492-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-015-0492-y