Abstract

Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), an omega-3 fatty acid abundant in fish oil, protects endothelial cells (EC) from lipotoxicity and triggers EC NO release. The latter is related to an elevation of cytosolic Ca2+. Although EPA has been shown to cause human EC cytosolic Ca2+ elevation, the mechanism is unclear. Microfluorimetric imaging was used here to measure free cytosolic Ca2+ concentration. EPA was shown to cause intracellular Ca2+ release in mouse cerebral cortex endothelial bEND.3 cells; interestingly, the EPA-sensitive intracellular Ca2+ pool(s) appeared to encompass and was larger than the Ca2+ pool mobilized by sarcoplasmic-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase inhibition by cyclopiazonic acid. EPA also opened a Ca2+ influx pathway pharmacologically distinct from store-operated Ca2+ influx. Surprisingly, EPA-triggered Ca2+ influx was Ni2+-insensitive; and EPA did not trigger Mn2+ influx. Further, EPA-triggered Ca2+ influx did not involve Na+–Ca2+ exchangers. Thus, our results suggest EPA triggered unusual mechanisms of Ca2+ release and Ca2+ influx in EC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), an omega-3 fatty acid, is a polyunsaturated fatty acid abundant in fish oil and microalgae. In addition to the latter sources, EPA can be synthesized from dietary α-linolenic acid. A number of beneficial health effects of EPA have been reported. For instance, EPA has been demonstrated to have beneficial effects on schizophrenia [1] and depression [2]. Recent evidence suggests that EPA is an antidepressant possibly because of inhibition of inflammatory cytokine production in microglia [3]. EPA can also ameliorate health status in cancer patients by inhibiting pro-inflammation cytokine production, increasing insulin sensitivity and improving calorie and protein uptake [4]. Chronic heart failure patients with dyslipidemia, have reduced inflammation, better cardiac performance and improved endothelial functions after EPA treatment [5]. EPA causes relaxation of agonist-contracted aortic rings and reduces agonist-triggered Ca2+ transients in aortic vascular smooth muscle of spontaneous hypertensive rats [6], in part accounting for the blood pressure-lowering effect of EPA.

Beneficial effects of EPA on endothelial cell (EC) functions have been studied. In human umbilical vein EC (HUVEC), EPA, by activating AMP-activated protein kinase, can protect palmitic acid-induced apoptotic death, and also alleviate palmitic acid-induced inhibition of eNOS and Akt [7]. EPA enhances neovasculogenesis and cell migration of human endothelial progenitor cells in vitro by up-regulating c-kit proteins and causing phosphorylation of ERK1/2, Akt and eNOS [8]. EPA reduces basal and insulin-stimulated endothelin-1 production in HUVEC [9]. EPA activates AMP-activated protein kinase, leading to enhanced eNOS phosphorylation and NO release in bovine aortic EC [10]. EPA has been shown to cause Ca2+ elevation in human EC, but the mechanisms for such a signal is unknown [11]. EPA directly stimulates human EC NO release [12].

In this work we investigated the effects of EPA on mouse cerebral cortical endothelial cells (bEND.3 cells). We observed that whilst EPA caused Ca2+ release from internal stores, it also triggered Ca2+ influx by opening a pathway unrelated to the store-operated Ca2+ channel. Interestingly, the EPA-triggered Ca2+ influx pathway is Mn2+-impermeable and Ni2+-insensitive.

Methods

Chemicals and cell culture

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), fetal calf serum, and tissue culture reagents were purchased from Invitrogen Corporation (Carlsbad, CA, USA). EPA and cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) were from Sigma-Aldrich. Fura-2AM was purchased from Calbiochem-Millipore. Brain microvascular bEND.3 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen).

Assay of cell viability

Cell viability was examined by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)- 2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) method. Cells were cultured in a 96-well plate at a density of 1.5 × 104/well, and were then treated with drugs for 24 h. MTT (final concentration at 0.5 mg/ml) was subsequently added to each well and then further incubated for 4 h. The culture medium was then removed and 100 μl of DMSO was added to each well for 15 min (with shaking) to dissolve the cells. The absorbance at 595 nm was measured using an ELISA reader and was used as an indicator of cell viability.

Microfluorimetric measurement of cytosolic Ca2+ and Mn2+ influx

Microfluorimetric measurement of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration was performed using Fura-2 as the Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent dye as described previously [13]. Briefly, cells were incubated with 5 μM Fura-2 AM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 1 h at 37 °C and then washed in extracellular bath solution which contained (mM): 140 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES (pH 7.4 adjusted with NaOH). When intracellular Ca2+ release was assayed, Ca2+-free solution was used. This Ca2+-free solution was the same as the extracellular bath solution mentioned above except that Ca2+ was omitted and 300 μM EGTA was supplemented. Cells were alternately excited with 340 and 380 nm using an optical filter changer (Lambda 10-2, Sutter Instruments). Emission was collected at 500 nm and images were captured using a CCD camera (CoolSnap HQ2, Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) linked to an inverted Nikon TE 2000-U microscope. For detection of Mn2+ influx, excitation wavelength was set at 360 nm (isosbestic point at which Fura-2 is insensitive to Ca2+) and emission was collected at 500 nm. In each experiment, 4–11 cells were imaged and the data from at least three separate experiments were averaged to yield mean ± SEM. Images were analyzed with MAG Biosystems Software (Sante Fe, MN). All imaging experiments were performed at room temperature (25 °C).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ANOVA was used to compare multiple groups, followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc test. The unpaired or paired Student’s t test was used where appropriate to compare two groups. A value of P < 0.05 was considered to represent a significant difference.

Results

EPA opened a Ca2+ influx pathway dissimilar to store-operated Ca2+ entry

An experiment was performed to examine whether EPA caused cell death. As shown in Fig. 1, treatment of cells with EPA at 30 μM for 24 h did not cause cell death. As a positive control, staurosporine (1 μM) caused 58% cytotoxicity.

EPA did not cause cell death. bEND.3 cells were incubated in the absence or presence of 30 μM EPA or 1 μM staurosporine for 24 h and MTT assay was performed to measure cell viability. Staurosporine was used as a positive control to inflict cell death. Results are mean ± SEM from 4 separate experiments. ***Significantly different (P < 0.001) from control

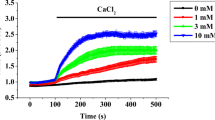

In experiments with extracellular Ca2+, exposure of bEND.3 cells to increasing concentrations of ΕPA caused a concentration-dependent rise in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 2a). The basal [Ca2+]i was stable with time (black line). EPA-elicited elevation in [Ca2+] i did not appear to be cell membrane damage, as revealed by negative trypan blue exclusion test (not shown). This finding is also consistent with results in Fig. 1 that EPA as high as 30 μM was not cytotoxic. EPA at 30 μM was chosen for further studies since it has been shown to offer cytoprotection and trigger NO release and vasodilation at 10–50 μM [14–16]. The EPA-triggered Ca2+ signal was smaller in Ca2+-free solution (Fig. 2b, black). This suggests EPA-triggered Ca2+ release from internal stores. Thus, the larger EPA-triggered Ca2+ signal in Ca2+-containing solution (Fig. 2b, red) suggests the later part of the signal was Ca2+ influx. To examine the reversibility of EPA-triggered Ca2+ signal, EPA-treated cells were rigorously washed for 6 min, but [Ca2+] i remained elevated, suggesting that the EPA effect was not readily reversible (Fig. 2c).

EPA-triggered Ca2+ release and influx. a [Ca2+] i in bEND.3 cells was monitored in Ca2+-containing bath solution. The cells were challenged with DMSO (black line) or different concentrations of EPA. b [Ca2+] i in bEND.3 cells was monitored in Ca2+-containing or Ca2+-free bath solution. The cells were challenged with 30 μM EPA. There is significant difference (P < 0.05) between the two groups beginning at 300 s and afterwards. c bEND.3 cells in Ca2+-containing bath solution were treated with 30 μM EPA and then washed. Results are mean ± SEM of 19–46 cells from 3 to 5 separate experiments

In the absence of bath Ca2+, exposure to 30 μM ΕPA triggered a [Ca2+] i elevation (of smaller magnitude), suggesting release of intracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 3a). Addition of Ca2+ resulted in a much larger [Ca2+] i elevation suggesting influx of extracellular Ca2+. Since Ca2+ store depletion could trigger store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), we examined whether the EPA-triggered Ca2+ influx was SOCE by deploying tetrandrine (TET), an SOCE blocker. We found that, rather surprisingly, TET did not inhibit the Ca2+ influx. We performed another set of experiments using CPA to trigger Ca2+ store depletion and SOCE (Fig. 3b, black line). Addition of TET substantially blocked SOCE (red line). When experiments were performed in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 3c), TET did not suppress EPA-triggered [Ca2+]i elevation. By contrast, TET strongly suppressed CPA-triggered [Ca2+] i elevation (Fig. 3d). Taken together, the data suggest the EPA-triggered Ca2+ influx was dissimilar to SOCE (but see Discussion).

EPA-triggered Ca2+ influx was insensitive to tetrandrine. a and b: [Ca2+]i in bEND.3 cells was monitored in Ca2+-free bath solution. The cells were treated with 30 μM EPA (a) or 30 μM CPA (b), followed by HCl (solvent) or tetrandrine (100 μM) addition and finally replenishment of 2 mM CaCl2. The final concentration of HCl was 0.33 mM, which did not significantly affect the pH of the bath solution. There is a significant difference (P < 0.05) between the two groups beginning at 719 s and afterwards. c and d: [Ca2+]i in bEND.3 cells was monitored in Ca2+-containing bath solution. The cells were treated with 30 μM EPA (c) or 30 μM CPA (d), followed by tetrandrine (100 μM) addition. Results are mean ± SEM of 26–44 cells from 4 to 6 separate experiments

EPA-triggered Ca2+ influx pathway was Ni2+-insensitive and Mn2+-impermeable

During EPA-triggered [Ca2+]i elevation, addition of 10 mM EGTA to chelate extracellular Ca2+ caused a decline in [Ca2+]i, possibly as a result of Ca2+ extrusion (Fig. 4a). This is supported by the observation of the reciprocal changes in fluorescence at 340 and 380 nm after EGTA addition (Fig. 4b). It is noted from the latter figure that emission intensity at both excitation wavelengths declined slowly right from the beginning, most likely due to inevitable photobleaching. If DMSO was added instead of EPA (Figs. 5d, 6d), emission intensity at both wavelengths continued to fade slowly. Thus, when compared to these DMSO controls, it becomes obvious that EPA addition caused an increase and decrease in fluorescence emission intensity at 340 and 380 nm excitation, respectively (Figs. 4b, 5b, 6b).

Effects of EGTA on EPA-triggered Ca2+ influx. bEND.3 cells were bathed in Ca2+-containing solution and were treated with 30 μM EPA followed by 10 mM EGTA. a Fura 2 ratio. b Fluorescence intensity (arbitrary units) at 340 and 380 nm excitation. Results are mean ± SEM of 28–35 cells from 4 to 7 separate experiments

Ni2+ did not block EPA-triggered Ca2+ influx. bEND.3 cells were bathed in Ca2+-containing solution and were treated with DMSO (a) or 30 μM EPA (c) followed by 10 mM Ni2+. Fura 2 ratios are shown in (a) and (c), while the corresponding fluorescence intensities (arbitrary units) at 340 and 380 nm excitations are shown in (b) and (d). Results are mean ± SEM of 23–32 cells from 4 to 5 separate experiments

Mn2+ did not permeate the EPA-triggered Ca2+ influx pathway. bEND.3 cells were bathed in Ca2+-containing solution and were treated with 30 μM EPA (a) or DMSO (c) followed by 1 mM Mn2+. Fura 2 ratios are shown in (a) and (c), while the corresponding fluorescence intensities (arbitrary units) at 340 and 380 nm excitations are shown in (b) and (d). Results are mean ± SEM of 29–43 cells from 4 separate experiments

We examined the pharmacological properties of this EPA-triggered Ca2+ influx pathway (Fig. 5). Addition of 10 mM Ni2+ did not significantly affect EPA-triggered [Ca2+]i elevation (Fig. 5a), suggesting Ni2+ did not block Ca2+ entry. This notion is supported by the observation that there was no reciprocal change in fluorescence at 340 and 380 nm after Ni2+ addition (Fig. 5b). Was there an influx of Ni2+ instead? If Ni2+ did enter the cell and since this metal ion quenches Fura-2 [17], a drop at 340 and 380 nm is expected. However, an examination revealed that the drop in fluorescence at these two wavelengths (after Ni2+) was similar in the absence and presence of EPA (Fig. 5d vs Fig. 5b), suggesting that Ni2+ influx was a leakage but not EPA-elicited.

We then examined how this EPA-triggered Ca2+ influx pathway was affected by Mn2+ (Fig. 6). Addition of 1 mM Mn2+ appeared to suppress EPA-triggered [Ca2+]i elevation (Fig. 6a). However, the expected reciprocal change in fluorescence at 340 and 380 nm (if [Ca2+]i was lowered, as in the case of EGTA; Fig. 4) was not observed after Mn2+ addition (Fig. 6b). Instead, fluorescence at both 340 and 380 nm dropped. Since Mn2+ quenches Fura-2 fluorescence [18], the result suggests Mn2+ entry. The stronger quench at 340 than 380 nm resulted in an apparent drop in ratio. However, the drop in fluorescence at these two wavelengths (after Mn2+) was similar in the absence and presence of EPA (Fig. 6d vs Fig. 6b), suggesting that Mn2+ influx was a leakage but not EPA-elicited. Therefore, the EPA-triggered Ca2+ influx pathway was not Mn2+-permeable. To verify this, we performed the Mn2+ influx experiment using a single excitation wavelength of 360 nm, the isosbestic point at which Fura-2 is insensitive to Ca2+ (Fig. 7). EPA at 30 μM did not promote but instead slightly inhibited Mn2+ influx; ionomycin was used as a positive control to promote entry of Mn2+ (Fig. 7a). EPA, even at 100 μM, did not promote but instead slightly inhibited Mn2+ influx (Fig. 7b).

EPA did not stimulate Mn2+ entry. a bEND.3 cells in Ca2+-containing solution were excited with 360 nm, treated with 1 mM Mn2+ and subsequently DMSO, 30 μM EPA or 5 μM ionomycin. There are significant differences (P < 0.05) between DMSO-EPA beginning at 180 s and afterwards, and between DMSO-ionomycin beginning at 164 s and afterwards. b The same protocol as in (a) in which 100 μM EPA and respective DMSO control were added. There are significant differences (P < 0.05) between DMSO-EPA between 159 and 569 s, and between DMSO-ionomycin beginning at 164 s and afterwards. The data are normalized with the initial fluorescence reading. Results are mean ± SEM of 28–51 cells from 3 to 5 separate experiments

EPA-sensitive intracellular Ca2+ store

The relationship between the EPA-sensitive and CPA-sensitive Ca2+ store was investigated (Fig. 8). In these experiments, we used a high concentration of EPA (100 μM) to cause more substantial Ca2+ release. When EPA was added to the cells in Ca2+-free bath, Ca2+ release was substantial and when CPA was added later, there was no more Ca2+ release. In another experiment, when CPA was added first, a subsequent EPA treatment still caused further Ca2+ release. These results suggest the EPA-sensitive Ca2+ store was larger and encompassed the CPA-sensitive one.

EPA-triggered Ca2+ signal was not affected in the absence of extracellular Na+

Next we examined whether the reverse mode of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) was involved in the EPA-triggered Ca2+ influx. To test this, EPA effects were investigated in normal Na+-containing extracellular bath solution or in an extracellular bath solution with NaCl completely substituted by choline chloride. The latter Na+-free solution was expected to favor the reverse mode of NCX. Results in Fig. 9 show that the EPA-triggered Ca2+ signal was not significantly affected in the absence of extracellular Na+, arguing against NCX involvement in EPA actions.

EPA-triggered Ca2+ signal was not affected in the absence of extracellular Na+. bEND.3 cells were bathed in normal Na+-containing extracellular bath solution or in an extracellular bath solution with NaCl completely substituted by choline chloride. The cells were treated with 30 μM EPA. There is no significant difference (P > 0.05) between the two groups. Results are mean ± SEM of 21–23 cells from 5 to 6 separate experiments

Discussion

Since the report by Okuda et al. [11] showing EPA could raise Ca2+ in human EC, very few works have been published showing the effect of EPA on EC Ca2+ signaling. Since a rise in EC cytosolic Ca2+ is essential in triggering NO release and hence vasodilatory effects, understanding the mechanism by which EPA raises EC Ca2+ is of great physiological and pharmacological interest. In this work we characterized the EPA-triggered Ca2+ influx pathway. Given that, in general, Mn2+ is a Ca2+ surrogate and Ni2+ is a Ca2+ channel blocker, the observation that the EPA-triggered Ca2+ influx pathway was Ni2+-insensitive and Mn2+-impermeable was unusual. It is noteworthy, however, that in human EC, EPA ethyl ester-triggered Ca2+ influx was blocked by Ni2+ [12], suggesting that EPA and its ester form might have subtly different pharmacological effects. EPA-triggered Ca2+ influx was not due to membrane damage, as suggested by our negative trypan blue exclusion test result and cell viability assay. In fact, if EPA did cause plasma membrane damage, Ni2+ and Mn2+ might be able to enter the cells, but they did not in the presence of EPA. We did consider whether the reverse mode of NCX provided a pathway for Ca2+ influx in EPA-treated cells. However, the data in Fig. 9 are inconsistent with NCX being a route for EPA-triggered Ca2+ influx. Indeed, EPA has been shown to inhibit both the forward and reverse activities of NCX1 expressed in HEK293 cells [19, 20].

A possible mechanism of EPA-stimulated Ca2+ influx is by its incorporation into the plasma membrane, increasing membrane fluidity and modulating ion channel activities. The fact that EPA effect could not be washed out (Fig. 2c) appears to be supportive of incorporation of EPA into the plasma membrane or organelles. Animals fed with EPA-rich diets have a much higher EPA percentage in the membrane phospholipids in neural tissues when compared to controls [21]. In EPA-treated aortic EC, plasma membrane fluidity, measured by 1,6-diphenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene polarization, was enhanced whilst total plasma membrane cholesterol content decreased [22]. The change in membrane fluidity, and/or EPA on its own, may modify channel activities. For instance, acute EPA treatment modulates Kv7.1 current amplitude and gating [23]. EPA also modulates L-type Ca2+ channel activities in rat cardiac myocytes [24]. Which ion channel(s) are modified by EPA to facilitate Ca2+ influx warrants further investigation (also see below).

What is also surprising is that the EPA-sensitive Ca2+ pool was larger and encompassed the CPA-sensitive pool. Did EPA inhibit sarcoplasmic-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA)? The ability of EPA to further release Ca2+ after maximal inhibition of SERCA by CPA (Fig. 7) is not in concordance with this proposal. Further, in view of the reported enhancing effects of EPA on brain and cardiac microsomal Ca2+ ATPase activity [25, 26; also see below), we consider inhibition of SERCA not a likely mechanism of EPA-induced Ca2+ release. It is remarkable that, in contrast to our observation that EPA caused emptying of the Ca2+ store in EC, it increased SR Ca2+ content in rat ventricular myocytes [27]. Thus, other Ca2+ pools such as mitochondria and Golgi apparatus may be worth examination. Dietary EPA supplementation has been shown to enhance the level of EPA in canine myocardial microsomes [26]. It is possible that extracellular addition of EPA (as in our case) caused incorporation of EPA into organelle membranes; this may eventually facilitate “Ca2+ leak” into the cytosol. Intriguingly, since EPA emptied the CPA-sensitive Ca2+ pool, it should have activated store-operated Ca2+ entry; however, EPA-triggered Ca2+ entry was insensitive to tetrandrine, which blocked CPA-triggered store-operated Ca2+ entry (Fig. 3). This discrepancy is difficult to explain but it is tempting to suggest that store-operated Ca2+ entry could have been activated in the presence of EPA, but channel pharmacological properties might have been altered due to EPA incorporation into the plasmalemma. This notion, of course, will need further verification.

While EPA did not affect basal Ca2+ level in polymorphonuclear leukocytes, pretreatment reduced agonist-induced Ca2+ rise [28]. It is interesting to note that EPA effect on vascular smooth muscle Ca2+ signaling is suppressive. In cultured rat vascular smooth muscle cells, a 24-day exposure to EPA has been demonstrated to lower basal Ca2+ and blunt agonist-triggered Ca2+ signaling [29]. A similar finding was obtained by Asano et al. [30] in which 7-day treatment with EPA caused membrane hyperpolarization, lowered resting Ca2+ levels and reduced agonist-triggered Ca2+ signaling (both release and influx) in A7r5 rat smooth muscle cells. In the same work, it could be demonstrated that EPA is slowly incorporated into the phosphospholipid fraction with time of EPA treatment. EPA has also been demonstrated to suppress L-type Ca2+ channel activities and inhibit vasopressin-triggered Ca2+ entry and proliferation in rat vascular smooth muscle cells [30]. Through all these actions, EPA could exert hypotensive and antiatherosclerotic effects.

Not only is EPA beneficial because of reciprocal changes in smooth muscle and EC Ca2+ signaling, it is also antiarrhythmic as it suppresses L-type currents in adult and neonatal rat ventricular myocytes [31]. EPA, by increasing activities of cardiac microsomal Ca2+ ATPase and hence lowering intracellular Ca2+ concentration, produces antiarrhythmic effects during myocardia infarction [26].

EPA offers protection in brain too. In rabbits fed with a high cholesterol-containing diet for 45 days, brain cortical microsomal Ca2+ ATPase activities were reduced; such reduction could be alleviated by co-feeding with EPA [25].

In conclusion, EPA caused Ca2+ release and Ca2+ influx via unusual mechanisms in bEND.3 cells. Given the versatile health effects of EPA, it is interesting and important to study the Ca2+ signaling triggered by this fatty acid in EC and other cell types, whose Ca2+ responses to EPA are very different from those in EC.

References

Peet M, Brind J, Ramchand CN, Shah S, Vankar GK (2001) Two double-blind placebo-controlled pilot studies of eicosapentaenoic acid in the treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 49:243–251

Martins JG (2009) EPA but not DHA appears to be responsible for the efficacy of omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in depression: evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Nutr 28:525–542

Lu DY, Tsao YY, Leung YM, Su KP (2010) Docosahexaenoic acid suppresses neuroinflammatory responses and induces heme oxygenase-1 expression in BV-2 microglia: implications of antidepressant effects for omega-3 fatty acids. Neuropsychopharmacology 35:2238–2248

Pappalardo G, Almeida A, Ravasco P (2015) Eicosapentaenoic acid in cancer improves body composition and modulates metabolism. Nutrition 31:549–555

Kohashi K, Nakagomi A, Saiki Y, Morisawa T, Kosugi M, Kusama Y, Atarashi H, Shimizu W (2014) Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on the levels of inflammatory markers, cardiac function and long-term prognosis in chronic heart failure patients with dyslipidemia. J Atheroscler Thromb 21:712–729

Engler MB, Ma YH, Engler MM (1999) Calcium-mediated mechanisms of eicosapentaenoic acid-induced relaxation in hypertensive rat aorta. Am J Hypertens 12:1225–1235

Lee CH, Lee SD, Ou HC, Lai SC, Cheng YJ (2014) Eicosapentaenoic acid protects against palmitic acid-induced endothelial dysfunction via activation of the AMPK/eNOS pathway. Int J Mol Sci 15:10334–10349

Chiu SC, Chiang EP, Tsai SY, Wang FY, Pai MH, Syu JN, Cheng CC, Rodriguez RL, Tang FY (2014) Eicosapentaenoic acid induces neovasculogenesis in human endothelial progenitor cells by modulating c-kit protein and PI3-K/Akt/eNOS signaling pathways. J Nutr Biochem 25:934–945

Chisaki K, Okuda Y, Suzuki S, Miyauchi T, Soma M, Ohkoshi N, Sone H, Yamada N, Nakajima T (2003) Eicosapentaenoic acid suppresses basal and insulin-stimulated endothelin-1 production in human endothelial cells. Hypertens Res 26:655–661

WuY Zhang C, Dong Y, Wang S, Song P, Viollet B, Zou MH (2012) Activation of the AMP-activated protein kinase by eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5 n-3) improves endothelial function in vivo. PLoS One 7:e35508

Okuda Y, Ezure M, Tsukahara K, Sawada T, Mizutani M, Katori T, Bannai C, Yamashita K (1994) Eicosapentaenoic acid enhances intracellular free calcium in cultured human endothelial cells. Biochem Med Metab Biol 51:166–168

Okuda Y, Kawashima K, Sawada T, Tsurumaru K, Asano M, Suzuki S, Soma M, Nakajima T, Yamashita K (1997) Eicosapentaenoic acid enhances nitric oxide production by cultured human endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 232:487–491

Leung YM, Huang CF, Chao CC, Lu DY, Kuo CS, Cheng TH, Chang LY, Chou CH (2011) Voltage-gated K+ channels play a role in cAMP-stimulated neuritogenesis in mouse neuroblastoma N2A cells. J Cell Physiol 226:1090–1098

Lee SE, Kim GD, Yang H, Son GW, Park HR, Cho JJ, Ahn HJ, Park CS, Park YS (2015) Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on the cytoprotection through Nrf2-mediated heme oxygenase-1 in human endothelial cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 66:108–117

Lee CH, Lee SD, Ou HC, Lai SC, Cheng YJ (2014) Eicosapentaenoic acid protects against palmitic acid-induced endothelial dysfunction via activation of the AMPK/eNOS pathway. Int J Mol Sci 15:10334–10349

Singh TU, Kathirvel K, Choudhury S, Garg SK, Mishra SK (2010) Eicosapentaenoic acid-induced endothelium-dependent and -independent relaxation of sheep pulmonary artery. Eur J Pharmacol 636:108–113

Fonteríz RI, López MG, García-Sancho J, García AG (1991) Alamethicin channel permeation by Ca2+, Mn2+ and Ni2+ in bovine chromaffin cells. FEBS Lett 283:89–92

Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY (1985) A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 260:3440–3450

Xiao YF, Ke Q, Chen Y, Morgan JP, Leaf A (2004) Inhibitory effect of n-3 fish oil fatty acids on cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchange currents in HEK293t cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 321:116–123

Ander BP, Hurtado C, Raposo CS, Maddaford TG, Deniset JF, Hryshko LV, Pierce GN, Lukas A (2007) Differential sensitivities of the NCX1.1 and NCX1.3 isoforms of the Na+–Ca2+ exchanger to alpha-linolenic acid. Cardiovasc Res 73:395–403

Philbrick DJ, Mahadevappa VG, Ackman RG, Holub BJ (1987) Ingestion of fish oil or a derived n-3 fatty acid concentrate containing eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) affects fatty acid compositions of individual phospholipids of rat brain, sciatic nerve and retina. J Nutr 117:1663–1670

Hashimoto M, Hossain S, Yamasaki H, Yazawa K, Masumura S (1999) Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid on plasma membrane fluidity of aortic endothelial cells. Lipids 34:1297–1304

Moreno C, de la Cruz A, Oliveras A, Kharche SR, Guizy M, Comes N, Starý T, Ronchi C, Rocchetti M, Baró I, Loussouarn G, Zaza A, Severi S, Felipe A, Valenzuela C (2015) Marine n-3 PUFAs modulate IKs gating, channel expression, and location in membrane microdomains. Cardiovasc Res 105:223–232

Hallaq H, Smith TW, Leaf A (1992) Modulation of dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channels in heart cells by fish oil fatty acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:1760–1764

Bekpinar S, Oner P, Altug T, Eryürek F, Sürmen E, Deniz G (1989) Influence of eicosapentaenoic acid and vitamin E on brain cortex Ca2+ ATPase activity in cholesterol-fed rabbits. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 59:127–130

Kinoshita I, Itoh K, Nishida-Nakai M, Hirota H, Otsuji S, Shibata N (1994) Antiarrhythmic effects of eicosapentaenoic acid during myocardial infarction. Enhanced cardiac microsomal (Ca2+–Mg2+)–ATPase activity. Jpn Circ J 58:903–912

Negretti N, Perez MR, Walker D, O’Neill SC (2000) Inhibition of sarcoplasmic reticulum function by polyunsaturated fatty acids in intact, isolated myocytes from rat ventricular muscle. J Physiol 523:367–375

Georgilis K, Klempner MS (1988) In vitro effects of omega-3 fatty acids on neutrophil intracellular calcium homeostasis and receptor expression for FMLP and LTB4. Inflammation 12:475–490

Locher R, Sachinidis A, Brunner C, Vetter W (1991) Intracellular free calcium concentration and thromboxane A2 formation of vascular smooth muscle cells are influenced by fish oil and n-3 eicosapentaenoic acid. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 51:541–547

Asano M, Nakajima T, Iwasawa K, Asakura Y, Morita T, Nakamura F, Tomaru T, Wang Y, Goto A, Toyo-oka T, Soma M, Suzuki S, Okuda Y (1999) Eicosapentaenoic acid inhibits vasopressin-activated Ca2+ influx and cell proliferation in rat aortic smooth muscle cell lines. Eur J Pharmacol 379:199–209

Xiao YF, Gomez AM, Morgan JP, Lederer WJ, Leaf A (1997) Suppression of voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ currents by polyunsaturated fatty acids in adult and neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:4182–4187

Acknowledgements

Y.M.L, K.L.W and K.S.C would like to thank China Medical University, Taiwan, and the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan for providing funding (103-2320-B-039-015-; 104-2320-B-039-030-; 104-2320-B-039-013-; 105-2320-B-039-028-; DMR-106-086; DMR-106-089). K.C.W would like to thank Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chiayi, for support (CMRPG6F0291).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Additional information

K.-S. Cheng, P. Chan and Y.-M. Leung have contributed equally as corresponding authors.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, KC., Wong, KL., Wang, ML. et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid triggers Ca2+ release and Ca2+ influx in mouse cerebral cortex endothelial bEND.3 cells. J Physiol Sci 68, 33–41 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12576-016-0503-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12576-016-0503-y