Abstract

Against the background of expanding parental choices and declining global birth rates, schools are experiencing rising competition regarding student enrolment. Schools have responded by strategically presenting information about their students’ academic achievement and whole-person development orientation in the hope of attracting parents’ interest. However, few studies have investigated the impact of these factors on student enrollment, particularly in the context of diverse school types and educational orientations. Accordingly, this study utilized data from 327 secondary schools in Hong Kong to examine the effects of academic achievement orientation and whole-person development orientation on student intake. Using hierarchical regression analysis, we found a positive association between high whole-person development orientation and student intake in aided schools with a strong academic development orientation. The result implies parents are increasingly concerned about their children’s academic achievement and whole-person development at school. The study contributes to a broader understanding of the factors influencing parental choice in high-performing education systems, providing valuable insights for policymakers and educators seeking to improve educational offerings, enhance school transparency, and be better aligned with parental expectations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the face of growing diversity of parental expectations, many countries have incorporated private government-dependent schools into their education systems (Berends, 2015; Education Bureau, 2001; Lubienski & Lee, 2016; West & Ylönen, 2010). It offers parents an expanded range of options but also intensifies schools’ fierce competition for students, given the global decline in birth rates in advanced societies (Barakat, 2014; Uba, 2010). Responding to the competition for enrollment, schools are now more proactive in highlighting their unique educational orientations and achievements to attract students, leveraging accessible information to influence parental preferences and secure a competitive advantage (Cheng et al., 2015; Jabbar, 2015; Lubienski, 2007; Urde & Koch, 2014). The intensifying rivalry between schools has spurred a growth in research focused on parental school choice, aiming to understand the determinants that sway parents’ decisions in a landscape where their choices can significantly bolster or impede a school’s success (Abdulkadiroğlu et al., 2020; Creed et al., 2021). Studies are rich in the USA, where the introduction of charter schools expanded parental school choices. These studies not only shed light on the significance of schools’ test scores and types but also on the demographic composition of the student body, demonstrating that these factors play a crucial role in the school selection process (Berends, 2015; Betts et al., 2006; Hastings & Weinstein, 2008). Furthermore, there is an exploration into how school choice serves as a mechanism for the (re)production of inequities (see Diamond & Lewis, 2022; Evans, 2021; Simms & Talbert, 2019). For example, Evans (2021) demonstrated how white middle-class parents’ ideologies in school choice processes may contribute to further expanding their children’s racial advantages and unintentionally reproducing racism, when these parents claimed to seek racial diversity and at the same time determine predominantly Black schools are undesirable as the anti-Black stereotypes of the white parents.

Amid this competitive environment, the presentation of school information becomes an important factor in influencing parental choices, directly affecting a school’s reputation and perceived quality. Indeed, parents assemble their general reputation toward schools and make informed decisions based on schools’ accessible information (Fung & Lam, 2011; Yettick, 2016). Parents typically seek as much available school information as possible to inform their decision-making and consequently, a school’s public representation of themselves plays an important role in attracting parents and students (Poikolainen, 2012). Therefore, schools’ information has also garnered school choice researchers’ attention. Hastings and Weinstein (2008) highlighted that test score information provided to parents associated with their choice of schools with higher academic achievement. In an informational intervention study, Cohodes et al. (2023) suggested that presenting information of low-graduation rate schools to parents significantly avoided their choices to these schools, showing that the availability of school information is important to parents and students. Concerning the accessibility of information in making school choice decision, Yettick (2016) studied the effects of different sources of information and argued that given the widespread availability of online information, parent websites and enrollment guides were associated with choices for schools with higher academic ratings. Yettick further noted parents also consult other parents rather than reference materials to select schools, acknowledging the reliance of personal networks in making school choice. Yet, the association between this information source and the selection of higher- or lower-quality schools was not evidenced. Yettick (2016) argued this may because parents are most likely seeking out friends similar to themselves.

Although prior studies tried to understand how specific information of schools associate with parental choice, the question of how schools’ information revealing their own educational orientations affect parental choices remains uncleared. This question is more complicated when more school types were introduced to students as the expanded school choices allows greater autonomy for private government-dependent schools to shape their own educational orientations, (Barbara, 2002; Berends, 2015; Education Bureau, 2001; West & Wolfe, 2019). For example, charter schools in the U.S.A. offer a wide variety of educational approaches from stressing only core disciplines to arts or sciences to Montessori schools to virtual schools (Carpenter, 2005).

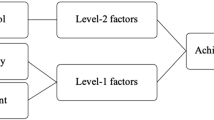

Drawing the insight from these studies, we extend the theoretical framework proposed by Kosunen (2013) to examine school choice from the schools’ information revealing their educational orientations and schools type perspective. Kosunen (2013) observed that parents sometimes focus on superficial aspects of education rather than the more substantive considerations discussed in the formal policy discourse. He contends that the schools’ information disclose about their educational orientations can affect parental choices. Generally, parents predominantly favor academic-oriented schools (Hastings & Weinstsin, 2008; Ho & Lu, 2019; Schneider & Buckley, 2002), while others have argued that parents value schools’ whole-person development orientation equally (Jabbar, 2015; Luyten et al., 2005). Kosunen (2013) assumed that publicly accessible information about a school’s academic achievements and whole-person development is vital for helping parents choose their preferred school.

This study aims to examine the factors influencing parental school choice within the Chinese context. The rationale for this focus stems from the widespread adoption of market-oriented educational reforms, such as school choice, vouchers, and charter schools, in the USA and the UK (Hoxby, 2003). These reforms have become increasingly prevalent globally since the early twenty-first century, inspired Chinese schools to pursue improvement and differentiation in ways that appeal to parents (Chan & Mok, 2001; Authors, 2019). Although valuable lessons can be learned from the studies conducted in the U.S. or European countries, it is important to recognize that the dynamics of educational systems and parental school choices in Chinese societies present a distinct context that worth additional attentions. For examples, the current educational landscape of Chinese societies was considered highly academic achievement oriented (Tan, 2019). Chinese societies like Hong Kong where Chinese consisting 93.6% of the population is also less racially and ethnically diverse, when compared to Western societies like the USA (Census & Statistics Department HKSAR, 2022; Ghosh, 2020). Therefore, cases from urban societies with expanded school choices and schools’ intensified competitions for students, for example, the Hong Kong society, may contribute to the literature on parents’ school choices within the Chinese context where the more homogeneous ethnical composition allows a research focus on the schools’ education orientation revealed from accessible information.

Thus, in response to the expanded school types since the introduction of private government-dependent schools in Chinese urban education and the diversified parental educational expectation, this paper utilize data collected from Hong Kong and explore the relationships among school types, schools’ accessible information revealing their academic and whole-person development orientations and student intakes. This study can contribute to the understanding of how parental preference of school reputation influences parental choice in urban education systems. By examining these relationships, the study can help schools better understand parents’ priorities when selecting schools for their children. In this way, schools can better allocate their resources to align with parents’ expectations and attract more students in a competitive landscape. Additionally, investigating the influence of different school types on the relationship between academic and whole-person development orientation in relation to student intake may provide policymakers with insights into the potential effects of various types of schools in meeting parental expectations.

Hong Kong context

The Hong Kong’s education system presents a valuable case for studying parental school choices due to its affinity with many urban education systems in which the expanding school choices, together with the declining birth rate, intensified the competition among schools for student enrollment. More importantly, Hong Kong’s education policies provide a more equitable information ground for parents, students, and the study to access schools’ information, compared to other regions where such disclosures may not be as strictly enforced (Education Bureau HKSAR, 2022b, 2022c). Also, the study benefits from Hong Kong’s school place allocation system and regulations that promote a fairer selection process in student enrollment, facilitating the investigation into parental school choices in relations to school types and schools’ information revealing their education orientations.

Managing schools in Hong Kong is competitive due to stringent regulations and a dwindling student population. Hong Kong’s ‘small government, big market’ philosophy of school regulation ties the funding and resource allocation for schools directly to student enrollment figures (Education Bureau HKSAR, 2022a; Tse, 2005; Zhou et al., 2015). Over the last twenty years, the ‘Consolidation of High Cost and Under-utilized Primary Schools’ policy, set forth by the Legislative Council Panel on Education (2003), has directed the operational management of schools. Initially aimed at the gradual discontinuation of small and isolated primary schools lacking adequate facilities and professional development for teachers, this policy has expanded to mandate the closure of any school, be it primary or secondary, that fails to attract at least 23 students to its first-year class. Compounding this issue, secondary school Year One enrollment has plummeted by 33% from 2011 to 2021, correlating with Hong Kong’s persistently low birth rates (Education Bureau HKSAR, 2022e). This trend led to the closure of six schools in early 2023 due to low student numbers (HKSAR, 2022).

In line with the trend in many education systems that is toward educational reform and increased school accountability, the Hong Kong education system has expanded school choices through offering private schools with government direct subsidies (Zhou et al., 2015). Schools in Hong Kong encompasses mainly government-aided schools and private schools receiving government subsidies. The former, typically operated by non-profit institutions or religious groups, offer affordable education due to substantial government funding, which offsets operational costs and enables students to attend at no charge. Two decades ago, the government launched the Direct Subsidy Scheme (DSS) to support private schools reliant on government funds. This scheme provide schools with subsidies, granting them more operational and curricular autonomy than their government-aided counterparts. Both aided and DSS schools in Hong Kong have adopted a balanced approach to education, fostering students’ academic and whole-person development (Ho & Lu, 2019). These schools are held accountable by the government for their performance in both academic and whole-person development domains, aligning with the priorities of other top-performing education systems worldwide (Ho et al., 2020).

In Hong Kong, schools’ information flow is relatively transparent as publicly funded schools (both aided and DSS schools) in Hong Kong are mandated by the government to undergo external school review every six years and to make the resulting reports, as well as school plans, available on their website for public inspection, including parental access (Education Bureau HKSAR, 2022b, 2022c). In the competitive environment for student enrollment, schools are also motivated to publicize their information on their websites or any accessible materials to showcase their commitment to student academic performance and whole-person development (Chan & Bray, 2014; Ho & Lu, 2019). For example, the education magazine Secondary School Profiles published by the government advisory committee on Home-School Co-operation provides a full list of schools for parents and students. The relative transparency of Hong Kong schools’ information is not only important for parents to identify their preferred schools, but it has also made the data of schools’ information available for the present study which examines the similar set of information exposed to parents for choosing schools.

The Hong Kong case in which the government regulates the school places allocation mechanism for a more equitable admission process also allows the study to focus on prenatal choices. Schools in Hong Kong may decide on their own admission criteria and weightings. However, the admission criteria and weightings adopted by the school must be fair, just, open and educationally sound, and must be made public prior to admission (Education Bureau HKSAR, 2023b). It does not require parents to provide unnecessary information like family backgrounds, preventing to some extent, schools’ assessment of family status to achieve a more equitable selection process. Schools may conduct interviews but no written tests in any forms should be conducted. Thus, with the transparency of school information and regulations on schools’ student selections, Hong Kong’s educational context allows the study to focus on investigating school choices in relations to school types and schools’ education orientations revealed from accessible information. Accordingly, we aim to explore whether private government-dependent and public schools present different patterns regarding how they present their academic and whole-person development orientation. Thus, the study is guided by the following research questions:

RQ1. How do academic and whole-person development orientations relate to student intake in schools in Hong Kong?

RQ2. Is there any interaction between the two orientations affecting student intake?

RQ3. How does the school funding type affect the relationship between academic and whole-person development orientation and student intake?

Theoretical framework

Drawing on school choice literature, we adopted Kosunen’s (2013) framework of parental perception of school reputation to understand the information presented by schools for building their reputation. Bernstein (2003) posited that school reputation is a combination of both instrumental and expressive orders, Kosunen (2013), expanded on this idea, associating instrumental order with parental expectations of academic achievement and expressive order with parental conceptions of how schools develop a student’s character through enduring schemes or structures. Kosunen further notes, however, that parents’ priorities may not always be aligned with formal policy discourse, and that sometimes parents focus on superficial aspects of education rather than the more substantive considerations that are discussed in policy discourse. Altrichter et al. (2011) also observed that many parents have limited knowledge of school operations and how teachers foster their children’s learning and development. Therefore, when selecting a school for their children, parents tend to prioritize a school’s general reputation built from publicly accessible information over hard facts that are often inaccessible (Fung & Lam, 2011; Jabbar, 2015). With the understanding of Kosunen’s framework and the influence of school reputation on school choice, we aim to obtain a better understanding of how school selections are made, specifically the distinction between academic development orientation (instrumental) and whole-person development orientation (expressive).

Academic development orientation

Parents expect schools to prioritize their children’s academic development, which adds to the students’ market value for the future (Bernstein, 2003; Jerrim et al., 2023; Kosunen, 2013). They tend to eliminate schools with a poor academic performance from consideration without examining their detailed profiles (Schneider & Buckley, 2002). This creates a cyclical process where the perceived favorable schools reinforce their academic performance through increased enrollment, while the perceived unfavorable schools suffer from lower enrollment and academic performance (Hasting & Weinstsin, 2008). In Hong Kong, parents have been found to choose academically oriented kindergartens (Fung & Lam, 2011), and they continue to prioritize academic performance in secondary school admissions (Ho & Lu, 2019). Thus, we propose:

H1

Schools with higher academic development orientation have a higher student intake.

Whole-person development orientation

A school that focuses on whole-person development is perceived as one that imparts high moral values to pupils in terms of conduct, character, and intellectual demeanor (Bernstein, 2003; Luyten et al., 2005). Whole-person development is undeniably essential for healthy personal and social development, serving as a school effectiveness indicator (Jabbar, 2015; Luyten et al., 2005). Studies have found that parents use their social and cultural resources to gather school information concerning character or whole-person development to aid in school choice decisions (Kosunen & Carrasco, 2014; Poikolainen, 2012). Hong Kong has undergone significant educational reforms in recent decades (Education Bureau HKSAR, 2014, 2017), emphasizing the need for schools to develop both formal and extracurricular activities to foster students’ whole-person development (Education Bureau HKSAR, 2022d, 2022f; Lee & Dimmock, 1999; Yuen et al., 2014). The focus on whole-person development aligns with Hong Kong parents’ growing interest in schools that cater to students’ balanced and holistic development, thus carrying considerable weight in their school selection process (Ma, 2009; Yuen & Grieshaber, 2009). We thus propose:

H2

Schools with higher whole-person development orientation have a higher student intake.

Studies also have revealed parents may prioritize the all-round development of their children, both academically and non-academically (Hasting & Weinstsin, 2008; Lee & Dimmock, 1999; Yuen et al., 2014). For instance, in a multiple-case study, Tan (2019) argued that even though Hong Kong has an exam-centric culture, parents still support educational reforms that aim to move away from high-stakes exams and focus on competencies and attitudes needed in today’s world. These studies suggest a possible interaction between academic and whole-person development orientation in influencing student intake. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3

The whole-person development orientation may interact with academic development orientation in influencing student intake.

Type of school

Considering the type of school as a factor in parents’ school selection is often noted in regarded research (see Berends, 2015; Gorard, 1996; West & Ylönen, 2010). Private government-dependent schools, with greater autonomy in curriculum, staffing, and administration, along with government subsidies, are perceived as more flexible in responding to parents’ needs and better equipped with innovative strategies to nurture children, resulting in parents’ preference for them over public schools worldwide (Berends, 2015; Butler et al., 2013; Chan & Tan, 2008; Dronkers & Avram, 2010). The introduction of types of schools, such as private, chartered, and public schools in the USA has offered parents and students an array of educational options that can cater to their preferences, goals, and needs (Lubienski & Lee, 2016). These choices improve students’ academic and non-academic achievements as students can receive education aligned with their individual goals and needs. Therefore, the type of school can play a pivotal role when parents select a school for their children. Many studies have noted the competition between public and private government-dependent schools, particularly in the United States and some European countries (e.g., Wilkinson, 2015; Wilson & Carlsen, 2016). Private government-dependent schools receive subsidies and possess more flexible governance structures, enabling them to cater to students’ diverse learning needs (Berends, 2015). These schools enjoy greater autonomy in terms of curriculum, staffing, school fees, and student selection (Storey, 2018; West & Wolfe, 2019). Consequently, private subsidized schools often hold a competitive advantage over public schools by shaping their educational orientations that appeal to parents.

Empirical evidence suggests that parents across 26 nations exhibit a preference for private government-dependent schools over public ones (Dronkers & Avram, 2010). Although it is noted that some studies from the U.S.A. suggested charter schools have come to resemble traditional schools through isomorphic behaviors (Lubienski & Lee, 2016; Renzulli et al., 2015), the preference to private government-dependent schools is particularly pronounced among parents with higher levels of engagement, as they perceive private-dependent schools as offering more flexible instructional methods, resulting in improved academic outcomes and better educational orientations for catering their children’s needs (Berends, 2015; Buddin, 2012; Butler et al., 2013). And findings of the isomorphic tendencies of charter schools from the U.S.A., though these studies are worthy noted, may not directly imply the similar situations in the Chinese context, given the regulations on private government-dependent schools in different regions are varied. For example, charter school students are generally required to participate in state testing for meeting the public funding accountability standards (Carpenter, 2005). While Hong Kong’s private government-subsidized schools do not have such requirements. This notion also suggests the study to explore school types in the Chinese context.

On the other hand, Hong Kong’s Direct Subsidy Scheme (DSS) schools which operate in a manner akin to private government-dependent schools, receive public funding to increase parental choice, and diversify educational offerings (Education Bureau HKSAR, 2001, 2023a). These DSS schools can offer curricula other than the Hong Kong public exams (i.e., The Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education Examination), for example, the International Baccalaureate curricula to cater to students’ learning diversity (Education Bureau HKSAR, 2023a, 2023b, 2023c). As of September 2021, there were 59 DSS secondary schools, which enjoy considerable autonomy in teacher management, funding allocation, and curricular matters (Education Bureau HKSAR, 2021). Thus, given the autonomy offered to DSS schools in Hong Kong, the isomorphic behaviors of schools need further investigation in the Chinese context and this study argues school types in Hong Kong may be related to schools’ individual educational orientations.

Unlike aided schools (public schools) which largely enroll students from designated school districts through a centrally coordinated student allocation system, DSS schools do not face enrollment restrictions based on school district. Consequently, DSS schools can be highly selective in screening and admitting students, which intensifies competition within the education system. Each year, the number of applicants for these prestigious schools can be 10 to 20 times the number of available vacancies.

In line with international trends, Hong Kong parents expect DSS schools to provide more diverse and innovative educational services for their children (Chan & Tan, 2008). Therefore, we hypothesize that DSS schools demonstrating a higher orientation toward both academic and whole-person development will be more appealing to parents and students:

H4

There will be a three-way interaction between academic development orientation, whole-person development orientation, and type of school.

Method

Sample and procedure

To collect data, we followed the similar process parents use as they decide on their children’s future school. In this way, we were utilizing secondary data to quantify schools’ academic and whole-person development orientations while obtaining information on schools’ student intake, which serves as an indicator of parental school choice. As previously argued, parents rely on information reflecting a school’s distinctive features when selecting a school for their children. In turn, schools are motivated to differentiate themselves from other schools by strategically showcasing their students’ academic achievements, curriculum features, and learning activities highlights through publicly accessible information.

In Hong Kong’s education system, official publications containing a school’s overview is unavailable. Therefore, parents often consult alternative sources, such as school websites, school plans and reports, and educational magazines prepared by local media companies and educational entities. These media companies invite schools to contribute overviews and statistics highlighting their students’ academic performance. Aided schools and DSS schools in Hong Kong are required to disclose their school development plans, annual school plans, and reports to comply with government regulations concerning school accountability (Education Bureau HKSAR, 2022f). The information published on schools’ websites and educational magazines can be verified through the Education Bureau. Publicly accessible information from these sources is deemed valid and reliable as it provides similar information that parents can access when choosing schools for their children. Therefore, we used secondary data including mandated school plans and reports, one education magazine Secondary School Profiles 2021/22 published by the government advisory committee on Home-School Co-operation, and the websites of secondary schools to assess the presented academic and whole-person development orientations of the schools and to retrieve information on the schools’ student intake. In doing so, this research ensures that the chosen data sources align with the actual information parents had access to.

To identify schools’ academic development orientation among these publications, we compiled information on each school’s overview and official school websites from the Secondary School Profiles 2021/22 to quantify their academic development orientation with indicators. For operationalizing whole-person development orientation, we retrieved school development plans and annual school plans and reports and coded for the learning experiences in terms of their educational purposes. The details of the measurements and operationalization are provided in the next sub-section.

There were 451 secondary schools in Hong Kong as of 2021 (Education Bureau HKSAR, 2023c). We collected information on student intake, public examination results, and university admissions from the magazine for 246 of these schools; we then cross-checked these data against the information available on each school’s official website. This information was used to indicate school academic development orientation. We then found 81 more schools’ academic achievement data from their websites. In total, we retrieved data from 327 schools. From the 327 school websites, we downloaded the most recent school development plan, annual school plan, and annual school report to code whole-person development orientation. This resulted in a final sample of complete data from 327 schools, representing 72.5% of secondary schools in Hong Kong. The study excluded 124 schools because they did not disclose their public exam results, which were considered out of the study’s scope. These excluded schools are typical schools from different school bandings in Hong Kong, while all 451 schools do not refuse students with special educational needs.

Measures

Academic development orientation was measured by the students’ overall public examination results and their university admissions. Nine items were used to indicate the schools’ academic performance in the public examination and university admission: “meeting the university’s minimum requirement rate;” “meeting the Chinese-language minimum requirement rate;” “meeting the English-language minimum requirement rate;” “meeting the mathematics minimum requirement rate;” “meeting the liberal studies minimum requirement rate;” “excellent performance in public examination per student;” “rate of admission to government-funded programs (sub-degree);” “rate of admission to government-funded programs (degree);” and “rate of admission to overseas programmes (degree).” We coded the number of academic performance disclosures from 0 to 9. The Cronbach’s α for all items was high at 0.912.

Whole-person development orientation was an aggregated measure coding schools’ provision of the five essential learning experiences defined by the Education Bureau HKSAR (2022d, 2022f): intellectual development, moral and civic education, community service, physical and esthetic development, and career-related experiences. We reviewed three school documents for each learning experience, with scores ranging from 0 to 10. To enhance the reliability of coding, we conducted a peer review coding of 10 samples. For the peer review, both researchers compiled a codebook. Then, we trained two research assistants to code the data using the codebook. Finally, we cross-checked their coding results which reached an inter-rater agreement of 0.813. Differences were resolved via discussion.

Student intake indicated parental school choice. In Hong Kong, the secondary school place allocation system can be divided into two stages: discretionary places and central allocation (Education Bureau HKSAR, 2023b). The discretionary places stage allows parents to apply directly to schools without residential district restrictions during the application period. Parents can consider the schools in all respects, such as their educational philosophy, tradition, religion, admission criteria, development, operation, and their children’s abilities, aptitude, and interests, to make a suitable and favorable school choice regardless of geographic district. In the central allocation stage, a computer-programmed allocation is implemented for students who have not been offered a place in the discretionary places stage based on the remaining school places. Thus, student intakes in the discretionary places stage genuinely represent the preference of parents and the schools’ popularity. Given that all schools in Hong Kong are designed to be able to hold a minimum of 24 classes, the sizes of Hong Kong school are argued not varying. Therefore, the actual number of enrolments in the stage of discretionary places was used to represent the student intake.

Type of school was coded as 0 for aided schools and 1 for DSS schools. Our study included 32 DSS schools and 295 aided schools, totaling 327 secondary schools.

Data analysis

Bivariate correlation analysis was conducted to measure the relationship between student intake, academic development orientation, whole-person development orientation, and the type of school. Hierarchical regression analysis was employed to predict student intake with academic development orientation, whole-person development orientation, and type of school as the predictor variables in step one. This analytical approach was chosen because it allows for a systematic examination of the unique contributions of each predictor variable, as well as their interactions, on the dependent variable (student intake). Additionally, hierarchical regression analysis is useful for investigating moderation effects, helping to reveal whether the relationship between predictor variables and the dependent variable depends on the level of another variable (Cohen et al., 2013).

In step two, a moderation test was implemented by including two-way interactions between each pair of these predictor variables (academic and whole-person orientations and type of school). Step three incorporated a three-way interaction among the three predictor variables. A mean centering of the variables was conducted which aided in interpreting interaction effects by minimizing multicollinearity issues (Aiken & West, 1991).

Results

Descriptive statistics for all study variables are presented in Table 1. The strongest associations were observed between student intake and type of school (r = 0.459, p < 0.01) and between student intake and academic development orientation (r = 0.292, p < 0.01), as well as between type of school and whole-person development orientation (r = 0.345, p < 0.01). This result shows a positive relationship between academic development orientation, whole-person development orientation, and student intake, with DSS schools generally having higher student intake than aided schools.

Table 2 presents the hierarchical regression results for Hypotheses 1 to 4. The table shows that academic development orientation was significantly associated with student intake (β = 0.17, p < 0.01), supporting Hypothesis 1. Whole-person development orientation was also significantly associated with student intake (β = 0.25, p < 0.01), supporting Hypothesis 2.

The two-way interaction between academic development orientation and whole-person development was not significantly related to student intake (β = 0.01, p = ns), leading to the rejection of Hypothesis 3. Although it is unusual to observe a two-way interaction that lacks statistical significance before conducting a three-way interaction analysis (Bliese & Castro, 2000), previous studies have revealed that private government-dependent schools possess a more flexible governance structure, leading to the difference between private government-dependent schools and public schools showing that the former enjoy greater autonomy in fine-tuning their educational orientations (Berends, 2015; Storey, 2018). The two-way interaction between academic development orientation and school type was significant (β = 0.17, p < 0.01), as was the interaction between whole-person development orientation and school type (β = − 0.25, p < 0.01). These results and the theoretical framework we propose prompted us to test the three-way interaction among the three variables, with school type moderating the main effect on student intake.

The result for the three-way interaction effects on student intake was significant (β = − 0.14, p < 0.01). To help interpret the three-way interaction, Figs. 1 illustrate the interactive effect of academic development orientation, whole-person development orientation, and type of school on student intake in aided schools and DSS schools. As presented in Fig. 1, for aided schools, academic development orientation was positively related to student intake when whole-person development orientation was high (β = 0.18, p < 0.01) and low (β = 0.15, p < 0.01), with a significant difference in the two slopes, t(295) = 2.06, p < 0.01. Plotting the interaction in terms of DSS schools, Fig. 1 illustrates different effects from Fig. 1; the relationship between academic development orientation and student intake was not significant when whole-person development orientation was high (β = 0.45, p = ns) and low (β = − 0.21, p = ns), with a considerable difference in the two slopes, t(32) = -0.62, p = ns.

Discussion

Our study examined the influence of school information in terms of two educational orientations (academic development and whole-person development) and school type on student intake, offering insights into the complex dynamics of school choice within the Chinese context via a case of Hong Kong. Our findings indicate that schools with higher academic development orientation (H1) and those with higher whole-person development orientation (H2) experience a higher student intake. These results extended prior studies suggesting the provision of academic performance information is positively associated with their choice of schools with higher academic achievement (Betts et al., 2006; Hastings & Weinstein, 2008; Schneider & Buckley, 2002). The study implies that, in addition to academic development, a whole-person development orientation also provides schools with a competitive edge in student enrollment. Our findings align with those of other studies showing the increasing emphasis on personal growth-related activities in addition to academic excellence in the education sector over the last few decades (Elias, 2009; Lovat, 2020; Margaret Podger et al., 2010). Regarding school type, private government-dependent schools (DSS schools) have a higher student intake compared to public schools, echoing previous empirical studies (Dronkers & Avram, 2010).

The insignificant two-way interaction between whole-person development orientation and academic performance orientation (H3) does not detract from the importance of the significant three-way interaction effect (H4). Instead, it suggests that the relationship between these two variables may be more complex than previously thought and that the effect of these variables on the outcome may be dependent on other factors, such as the type of school. The statistically significant three-way interaction analysis result uncovers the nuanced interplay among academic development orientation, whole-person development orientation, and school type, showcasing their collective influence on student intake (H4). Notably, aided schools demonstrated a significant relationship with both orientations; however, such a significance was not found in DSS Schools, which could be attributed to the limited sample size (n = 32). Thus, the impact of academic and whole-person development orientation on the student intake of DSS Schools is not interpreted here. Nevertheless, Fig. 1 demonstrates a notable difference between aided schools and DSS Schools regarding the impact of their educational orientations on student enrollment. As shown in Fig. 1, the slopes indicate that aided schools had a high whole-person development orientation resulting in a more substantial impact on student intake on average when they concurrently exhibited high academic development orientation. This finding suggests that parents’ value aided schools that prioritize not only academic achievement but also those that foster the whole-person development of their children, indicating a growing recognition of the importance of creating a balance between academic and personal development. The findings contribute evidence toward better understanding global educational reforms. While there is a worldwide shift toward promoting whole-person development in students (Sivan & Siu, 2019); much of East Asian education remains examination-focused (Tan, 2019). Although Hong Kong is widely recognized for its exam-oriented education culture, with university entrance largely determined by public examination results (Fok & Yu, 2014), our findings show that Hong Kong parents also consider their children’s whole-person development when choosing schools. This finding aligns with Tan’s (2019) case study of three East Asian localities, revealing that parents in Hong Kong generally support educational reforms aimed at moving away from an exam-centric culture.

Our study in a Chinese society also contributes to the global literature on school choice and school information. While prior innervational studies confirmed the provision of certain school information, for example, graduation rate and test score, influenced parental school choice, and limited research examined publicly assessable school information (Cohodes et al., 2023; Hastings & Weinstein, 2008). Given the relatively higher information transparency in Hong Kong as discussed previously, our study is attempted to explore publicly available schools’ information with a focus on educational orientations revealed from the information through which parents constructed the reputations of schools (Kosunen, 2013). Our findings suggested an intricate interplay among educational orientations and school types on student intake, agreeing studies contending the introduction of more school types allow greater autonomy for educational designers to shape their own educational orientations and diversify prenatal school choice (Berends, 2015; West & Wolfe, 2019). While other studies in the USA suggested the isomorphic tendency of charter schools to mirror traditional schools (Lubienski & Lee, 2016; Renzulli et al., 2015). The significant three-way interaction among educational orientations, school type, and student intake in a Chinese society highlighted that the introduction of private government-dependent school may be influenced by the contextual variations, for example, government regulations, highlighting the complexity of the implementing private government-dependent school across different regions.

Furthermore, our findings expand upon the school choice literature by presenting evidence that emphasizes how solely focusing on academic-oriented educational goals does not meet parental expectations for schooling. Additionally, we examined the intricate interplay among educational orientations and school types on student intake, highlighting that under the condition of high academic development orientation, aided schools demonstrate a more substantial impact on student intake when they also have a high whole-person development orientation. However, this relationship was not observed in private government-dependent schools (DSS schools) and may have been caused by the small and polarized population of DSS schools. This finding enriches Kosunen’s bipartite model by considering school type. Drawing on secondary data in Hong Kong, our findings reveal that the communication of academic achievement and whole-person development orientations influence how parents perceive school reputation (Kosunen, 2013). Although we did not find significant results to interpret the relationship among the two educational orientations and private government-dependent schools, we encourage future research to investigate this aspect further.

From a practical perspective, our findings highlight the interaction between high academic achievement and whole-person development offering consolidated insights for schools while suggesting that schools strive to balance resources between academic and whole-person development. This approach appears to attract more students and is better align with parental and societal expectations. While studies show parents emphasize a school’s overall reputation when selecting a school for their children (Fung & Lam, 2011; Jabbar, 2015), parents may have some vague, anecdotal observation, but not a thorough analysis. This study links data from different sources and offers inferred relationships between the school endeavors (promotion of academic and whole-person development) and results (student intake). Schools’ publicly accessible information becomes a source for parents to construct schools’ reputation. However, unlike companies where marketing or branding activities can precede production, schools must organize learning activities before publicizing them. Thus, our findings imply that a dual allocation of resources toward both academic and whole-person development can enhance a school’s competitiveness in terms of student enrollment, as opposed to focusing solely on exceling in students’ academic performance. The findings underscore the importance of both intellectual and pastoral care for developing students, which can lead to schools increasing their student intake while bolstering their reputation. By integrating a whole-person development orientation into education, schools can equip students with the skills and experiences necessary for lifelong learning, active societal contributions, and citizenship in the twenty-first century (Durlak et al., 2011; Karsten et al., 2002; Margaret Podger et al., 2010; Pan et al., 2017).

Finally, we found that parents aiming to send their children to aided schools where value both academic and whole-person development. To meet these expectations, policymakers should offer guidance to schools on resource allocation and introduce funding schemes that support whole-person development. This would help ensure a balanced approach to education that addresses the needs of the whole student. Moreover, education initiatives for parents can help them better understand the purpose of schooling, school operations, and factors to consider when selecting a school. These measures may facilitate optimal matching between schools and prospective students, ultimately benefiting all parties involved (Ellison & Aloe, 2018).

Limitations and future research

Several limitations of the current study warrant discussion and suggestions for future research. First, this study focused on secondary data in Hong Kong, so the findings cannot be generalized to other cultural contexts. More quantitative studies should be conducted in other educational contexts to uncover how publicly assessable school information shape parents’ school choice. Second, although we utilized a large mixed-methods dataset, it employed a cross-sectional analysis, with independent and dependent data occurring within a common time range. Longitudinal research designs that collect independent variable data from earlier time points and dependent variable data from later or multiple time points could yield more robust findings helping to expose causal relationships. Third, the current study encompassed 72.5% of Hong Kong’s secondary schools, as the public examination performance data for the remaining schools were not obtainable through our data collection methods. Consequently, our findings may not extend to all secondary schools in the region. Nevertheless, the study was designed to mirror the process by which parents typically gather and assess publicly available information (Kosunen, 2013), focusing on the analysis of publicly available data, such as school plans, reports, and website content. The absence of accessible public examination results for the excluded schools raises an unresolved issue: whether this lack of data reflects a deliberate obfuscation strategy or simply inadequate public communication, which should be investigated in future research. Lastly, the scope of data analyzed in this study was limited to certain sources, which might not encompass the full spectrum of information parents consider when selecting schools for their children. While this research provides a detailed examination of the educational orientations communicated through readily accessible school information, particularly in the context of Hong Kong’s exam-centric educational landscape and its implications for whole-person development, it may not capture every nuance. Other significant aspects, such as school values, school–parent collaborations, and community involvement and partnerships, might also be discerned from the available data and be influential to parents. Factors beyond the accessible information—such as parents’ digital literacy, social and cultural capital, peer recommendations, social media influence, local knowledge, and varying parenting styles—may also substantially shape parents’ preferences when choosing schools (Dustan, 2018; Ho et al., 2023; Yettick, 2016). Future studies could aim to include these elements to present a more comprehensive view of the factors influencing parental school choice, exploring how these factors interact with school type, academic development orientation, and whole-person development orientation to influence parental decision-making.

References

Abdulkadiroğlu, A., Pathak, P. A., Schellenberg, J., & Walters, C. (2020). Do parents value school effectiveness? American Economic Review, 110(5), 1502–1539. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20172040

Aiken, L. G., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

Altrichter, H., Bacher, J., Beham, M., Nagy, G., & Wetzelhütter, D. (2011). The effects of a free school choice policy on parents’ school choice behaviour. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 37(4), 230–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2011.12.003

Barakat, B. (2014). A ‘recipe for depopulation’? School closures and local population decline in Saxony. Population, Space and Place, 21(8), 735–753. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1853

Berends, M. (2015). Sociology and school choice: What we know after two decades of charter schools. Annual Review of Sociology, 41(1), 159–180. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112340

Bernstein, B. (2003). Class, codes and control. Routledge.

Betts, J. R., Rice, L. A., Zau, A. C., Tang, Y. E., & Koedal, C. R. (2006). Does school choice work?: Effects on student integration and achievement. Public Policy Institute of California.

Bliese, P. D., & Castro, C. A. (2000). Role clarity, work overload and organizational support: Multilevel evidence of the importance of support. Work & Stress, 14(1), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/026783700417230

Buddin, R. (2012). The impact of charter schools on public and private school enrolments (Policy Analysis No. 707). Cato Institute. Retrieved April 16, 2023, from https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/impact-charter-schools-public-private-school-enrollments

Butler, J. S., Carr, D. A., Toma, E. F., & Zimmer, R. (2013). Choice in a world of new school types. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 32(4), 785–806. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.21711

Carpenter, D. M. (2005). Playing to type? Mapping the charter school landscape. Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

Census and Statistics Department HKSAR. (2022). 2021 Population census: Main results.

Chan, C., & Bray, M. (2014). Marketized private tutoring as a supplement to regular schooling: Liberal studies and the shadow sector in Hong Kong secondary education. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 46(3), 361–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2014.883553

Chan, D., & Mok, K.-H. (2001). Educational reforms and coping strategies under the tidal wave of marketisation: A comparative Study of Hong Kong and the Mainland. Comparative Education, 37(1), 21–41.

Chan, D., & Tan, J. (2008). Privatization and the rise of direct subsidy scheme schools and independent schools in Hong Kong and Singapore. International Journal of Educational Management, 22(6), 464–487. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540810895417

Cheng, A., Trivitt, J. R., & Wolf, P. J. (2015). School choice and the branding of Milwaukee private schools. Social Science Quarterly, 97(2), 362–375. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12222

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2013). Applied multiple regression/Correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Cohodes, S. R., Corcoran, S. P., Jennings, J. L., & Sattin-Bajaj, C. (2023). When Do Informational Interventions Work? Experimental Evidence From New York City High School Choice. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737231203293

Legislative Council Panel on Education. (2003). Consolidation of high cost & under-utilized primary schools (CB(2)1826/02–03(01)).

Creed, B., Jabbar, H., & Scott, M. (2021). Understanding charter school leaders’ perceptions of competition in Arizona. Educational Administration Quarterly, 57(5), 815–858. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161x211037337

Diamond, J. B., & Lewis, A. E. (2022). Opportunity hoarding and the maintenance of “White” educational space. American Behavioral Scientist, 66(11), 1470–1489. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027642211066048

Dronkers, J., & Avram, S. (2010). A cross-national analysis of the relations of school choice and effectiveness differences between private-dependent and public schools. Educational Research and Evaluation, 16(2), 151–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2010.484977

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Dustan, A. (2018). Family networks and school choice. Journal of Development Economics, 134, 372–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.06.004

Education Bureau HKSAR. (2001). Direct Subsidy Scheme (DSS).

Education Bureau HKSAR. (2014). Basic education curriculum guide: To sustain, deepen and focus on learning to learn (Primary 1–6).

Education Bureau HKSAR. (2017). Secondary education curriculum guide 2017.

Education Bureau HKSAR. (2021). List of direct subsidy scheme schools in 2021/22 school year. Retrieved August 28, 2022, from https://www.edb.gov.hk/attachment/en/edu-system/primary-secondary/applicable-to-primary-secondary/direct-subsidy-scheme/index/school_list%20_e_tc.pdf

Education Bureau HKSAR. (2022a). Expanded operating expenses block grant user guide for aided schools which have established an incorporated management committee.

Education Bureau HKSAR. (2022b). External school review: Information for schools.

Education Bureau HKSAR. (2022c). Guidelines on the compilation of school development plan annual school plan school report.

Education Bureau HKSAR. (2022d, May 31). Life-wide learning for the five essential learning experiences. Retrieved May 9, 2023, from https://www.edb.gov.hk/en/curriculum-development/curriculum-area/life-wide-learning/know-more/essential-learning-experiences.html

Education Bureau HKSAR. (2022e). Student enrolment statistics, 2021/22 (kindergartens, primary and secondary schools).

Education Bureau HKSAR. (2022f, May 31). What is life-wide learning strategy?. Retrieved May 9, 2023, from https://www.edb.gov.hk/en/curriculum-development/curriculum-area/life-wide-learning/know-more/strategy.html

Education Bureau HKSAR. (2023a, October 25). General information on Direct Subsidy Scheme (DSS). Retrieved November 24, 2023, from https://www.edb.gov.hk/en/edu-system/primary-secondary/applicable-to-primary-secondary/direct-subsidy-scheme/info-sch.html

Education Bureau HKSAR. (2023b, April 21). General information on secondary school places allocation (SSPA) system. Retrieved April 24, 2023, from https://www.edb.gov.hk/en/edu-system/primary-secondary/spa-systems/secondary-spa/general-info/

Education Bureau HKSAR. (2023c, April 27). Figures and Statistics. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://www.edb.gov.hk/en/about-edb/publications-stat/figures/index.html

Elias, M. J. (2009). Social-emotional and character development and academics as a dual focus of educational policy. Educational Policy, 23(6), 831–846. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904808330167

Ellison, S., & Aloe, A. M. (2018). Strategic thinkers and positioned choices: Parental decision making in urban school choice. Educational Policy, 33(7), 1135–1170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904818755470

Evans, S. A. (2021). “I wanted diversity, but not so much”: Middle-Class white parents, school choice, and the persistence of Anti-Black stereotypes. Urban Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420859211031952

Fok, P., & Yu, Y. (2014). The curriculum reform in new senior secondary education of Hong Kong: Change and immutable. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 9(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.3966/181653382014030901001

Fung, K. H., & Lam, C. C. (2011). Empowering parents' choice of schools: the rhetoric and reality of how Hong Kong kindergarten parents choose schools under the voucher scheme. Current Issues in Education, 14(1). https://cie.asu.edu/ojs/index.php/cieatasu/article/view/635

Ghosh, I. (2020, December 28). Visualizing the U.S. population by race. Visual Capitalist. Retrieved December 22, 2023, from https://www.visualcapitalist.com/visualizing-u-s-population-by-race/

Gorard, S. A. (1996). Three steps to ‘Heaven’? The family and school choice. Educational Review, 48(3), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013191960480304

Hastings, J. S., & Weinstein, J. M. (2008). Information, school choice, and academic achievement: Evidence from two experiments. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(4), 1373–1414. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2008.123.4.1373

Ho, M. C. S., & Lu, J. (2019). School competition in Hong Kong: A battle of lifting school academic performance? International Journal of Educational Management, 33(7), 1483–1500. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-07-2018-0201.

Ho, E. S. C., Tse, T. K. C., & Sum, K. W. (2020). A different ‘feel’, a different will: Institutional habitus and the choice of higher educational institutions in Hong Kong. International Journal of Educational Research, 100, 101521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.101521

Ho, C. S. M., Lee, T. T., & Lu, J. (2023). Enhancing school appeal: How experiential marketing influences perceived school attractiveness in the urban context. Education and Urban Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131245231205261

Hoxby, C. M. (2003). School choice and school productivity. Could school choice be a tide that lifts all boats? In C. M. Hoxby (Ed.), The economics of school choice (pp. 287–342). University of Chicago Press.

Jabbar, H. (2015). “Every kid is money” market-like competition and school leader strategies in New Orleans. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(4), 638–659. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373715577447

Jerrim, J., Prieto-Latorre, C., Lopez-Agudo, L. A., & Marcenaro-Gutierrez, O. D. (2023). Parents’ (dis)satisfaction with schools: Evidence from longitudinal administrative data from Spain. Educational Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2022.2153804

Karsten, S., Cogan, J. J., & Grossman, D. L. (2002). Citizenship education and the reparation of future teachers: A study. Asia Pacific Education Review, 3, 168–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03024910

Kosunen, S. (2013). Reputation and parental logics of action in local school choice space in Finland. Journal of Education Policy, 29(4), 443–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2013.844859

Kosunen, S., & Carrasco, A. (2014). Parental preferences in school choice: Comparing reputational hierarchies of schools in Chile and Finland. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 46(2), 172–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2013.861700

Lee, J. C., & Dimmock, C. (1999). Curriculum leadership and management in secondary schools: A Hong Kong case study. School Leadership & Management, 19(4), 455–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632439968970

Lovat, T. (2020). Holistic learning versus instrumentalism in teacher education: Lessons from values pedagogy and related research. Education Sciences, 10(11), 341–352. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10110341

Lubienski, C. (2007). Marketing schools: Consumer goods and competitive incentives for consumer information. Education and Urban Society, 40(1), 118–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124507303994

Lubienski, C., & Lee, J. (2016). Competitive incentives and the education market: How charter schools define themselves in metropolitan Detroit. Peabody Journal of Education, 91(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2016.1119582

Luyten, H., Visscher, A., & Witziers, B. (2005). School effectiveness research: From a review of the criticism to recommendations for further development. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 16(3), 249–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243450500114884

Ma, H. K. (2009). Moral development and moral education: An integrated approach. Educational Research Journal, 24(2), 293–326.

Margaret Podger, D., Mustakova-Possardt, E., & Reid, A. (2010). A whole-person approach to educating for sustainability. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 11(4), 339–352. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676371011077568

Pan, H. L. W., Nyeu, F. Y., & Cheng, S. H. (2017). Leading school for learning: Principal practices in Taiwan. Journal of Educational Administration, 55(2), 168–185. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-06-2016-0069

Poikolainen, J. (2012). A case study of parents’ school choice strategies in a Finnish urban context. European Educational Research Journal, 11(1), 127–144. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2012.11.1.127

Renzulli, L. A., Barr, A. B., & Paino, M. (2015). Innovative education? A test of specialist mimicry or generalist assimilation in trends in charter school specialization over time. Sociology of Education, 88, 83–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040714561866

Schneider, M., & Buckley, J. (2002). What do parents want from schools? Evidence from the Internet. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 24(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737024002133

Simms, A., & Talbert, E. (2019). Racial residential segregation and school choice: How a market-based policy for K-12 school access creates a “parenting tax” for Black parents. Phylon, 1, 33–57.

Sivan, A., & Siu, G. P. K. (2019). Extended Education for Academic Performance, Whole Person Development and Self-fulfilment: The case of Hong Kong. In S. H. Bae, J. L. Mahoney, S. Maschke, & L. Stecher (Eds.), International Developments in Research on Extended Education: Perspectives on extracurricular activities, after-school programmes, and all-day schools (1st ed., pp. 211–222). Verlag Barbara Budrich.

Storey, V. A. (2018). A comparative analysis of the education policy shift to school type diversification and corporatization in England and the United States of America: Implications for educational leader preparation programs. International Journal of Educational Leadership Preparation, 13(1), 1–23.

Tan, C. (2019). Parental responses to education reform in Singapore, Shanghai and Hong Kong. Asia Pacific Education Review, 20(1), 91–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-018-9571-4

The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). (2022, January 26). LCQ19: Measures to cope with the decline in student population.

Tse, T. K. (2005). Quality education in Hong Kong: The anomalies of managerialism and marketization. In L. S. Ho, P. Morris, & Y. Chung (Eds.), Education reform and the quest for excellence: The Hong Kong story (pp. 99–126). Hong Kong University Press.

Uba, K. (2010). Save our school! What kinds of impact have protesters against school closures in Swedish local politics? Statsvetenskaplig Tidsskrift, 112(1), 96–104.

Urde, M., & Koch, C. (2014). Market and brand-oriented schools of positioning. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 23(7), 478–490. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-11-2013-0445

West, A., & Wolfe, D. B. (2019). Academies, autonomy, equality and democratic accountability: Reforming the fragmented publicly funded school system in England. London Review of Education, 17(1), 70–86. https://doi.org/10.18546/lre.17.1.06

West, A., & Ylönen, A. (2010). Market-oriented school reform in England and Finland: School choice, finance and governance. Educational Studies, 36(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055690902880307

Wilkinson, G. (2015). Marketing in schools, commercialization and sustainability: Policy disjunctures surrounding the commercialization of childhood and education for sustainable lifestyles in England. Educational Review, 68(1), 56–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2015.1058750

Wilson, T. S., & Carlsen, R. L. (2016). School marketing as a sorting mechanism: A critical discourse analysis of charter school websites. Peabody Journal of Education, 91(1), 24–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2016.1119564

Yettick, H. (2016). Information is bliss: Information use by school choice participants in Denver. Urban Education, 51, 859–890. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085914550414

Yuen, G., & Grieshaber, S. (2009). Parents’ choice of early childhood education services in Hong Kong: A pilot study about vouchers. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 10(3), 263–279. https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2009.10.3.263

Yuen, M., Chan, R. T., & Lee, B. S. (2014). Guidance and counseling in Hong Kong secondary schools. Journal of Asia Pacific Counseling, 4(2), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.18401/2014.4.2.3

Zhou, Y., Wong, Y. L., & Li, W. (2015). Educational choice and marketization in Hong Kong: The case of direct subsidy scheme schools. Asia Pacific Education Review, 16(4), 627–636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-015-9402-9

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Education University of Hong Kong. This study was supported by funding support from the Research Grant Council of Hong Kong through the General Research Fund Project #18610719.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no competing interests to declare.

Ethical approval

Because this study was an analysis of secondary data with no identifying information, it was exempted from Institutional Review Board Approval.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ho, C.S.M., Lu, J. & Liu, L.C.K. Advertising a school’s merits in Hong Kong: weighing academic performance against students whole-person development. Asia Pacific Educ. Rev. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-024-09960-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-024-09960-7