Abstract

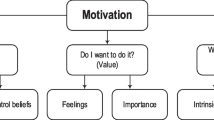

Private tutoring has become a worldwide phenomenon, yet there is little empirical evidence for the main factors leading the demand for private tutoring across nations. Using data from the Third International Mathematics and Science Study of 2003, this study classified the countries into four different groups according to the proportion of student participation in private tutoring and student achievement. Then, the study explored student- and school-level factors influencing the demand for private tutoring. From the HGLM analysis, the results revealed that the demand for private tutoring in Korea and Taiwan, which have higher participation rates in private tutoring and high-school-quality levels, is mostly explained by student-level variables (educational aspirations, instrumental motivation, self-confidence, and father’s education) and school context variables (the community size and school SES). Meanwhile, the demand for private tutoring in the Philippines and Romania, both of which have high incidences of private tutoring and low-school-quality levels, varies widely among schools, and many of the school process variables (e.g., the use of remedial classes, amount of school homework, frequency of tests, and the use of grouping by ability) account for the relationships with private tutoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although there can be some argument against using the simple means of achievement scores as a proxy for school quality, we employed the simple country means as a proxy for quality of school education based on the vast number of OECD publications that discuss the quality of education systems in participating countries using the simple country means. Besides these OECD publications, there are quite a few studies using simple means of achievement scores as a proxy for school quality (Fuller and Clarke 1994; Hanushek et al. 2007; Lockheed and Levin 2012).

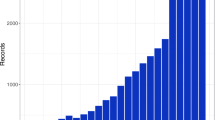

To cross-validate these groupings of countries, we looked at another set of international data from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) in 2006 despite the fact that these data differ in terms of the target population and the operational definition of mathematical ability. PISA deals with 15-year-olds, while TIMSS deals with eighth-graders. Moreover, PISA assesses mathematical literacy in more general terms, while TIMSS assesses the mathematical abilities taught in schools. In spite of these differences between the PISA and TIMSS studies, we found that 13 out of the 26 countries which participated in both studies were classified into the same type. If we exclude the group 3 countries in the lower left corner in Fig. 1, 12 out of 19 countries were classified into the same group. The problem with group 3 countries seems to be due to the differences in the mean private tutoring level among PISA and TIMSS participating countries. The mean private tutoring level was 46 % for PISA countries and 49 % for TIMSS countries.

In the case of Romania, a 1994 study of Grade 12 pupils in a national sample found that 32.0 % in rural areas and 58.0 % in urban areas received private supplementary tutoring (UNESCO 2000). Also, the private tutoring courses often cost as much as a full year’s tuition in a private university (World Bank 1996). In the case of South Korea, government statistics indicate that 75.1 % of primary and secondary students received private tutoring, and approximately 20.9 trillion Korean won was spent on private tutoring expenses in 2008 (Korean National Statistics Office 2009). In Taiwan, government statistics indicate that in 1998, 5,536 buxibans (tutoring centers) were providing services to 1,891,096 students (Taiwan Ministry of Education 1999). Also, Zeng (1999: 52) reported that the total income of the academic buxibans was equivalent to US $212 million. Finally, a number of Filipino students are known to enroll in review centers or to hire private tutors to assist them in preparing for examinations and to ensure their admission into prestigious schools in keeping with the growth of structured, outside-school activities such as review centers (CHED CMO No. 49, 2006) in the Philippines along with the practice of high-stakes testing such as the National College Entrance Examinations (NCEE) and National Secondary Achievement Test (NSAT).

Because the HGLM using the dummy dependent variable does not provide information on partitioning the total variation into between-school and within-school variation, we employed the HLM model for this purpose. For the HLM analysis, the dependent variable was how often one participated in private math tutoring in the last year, one indicating “never or almost never” to four indicating “almost every day.”

The marginal effect for a dummy variable was calculated for typical students.

References

Baker, D., Akiba, M., LeTendre, G., & Wiseman, A. (2001). Worldwide shadow education: Outside-school learning, institutional quality of schooling, and cross-national mathematics achievement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 23(1), 1–17.

Baker, D., & LeTendre, G. K. (2005). National differences, global similarities: World culture and the future of schooling. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Biswal, P. B. (1999). Private tutoring and public corruption: A cost-effective education system for developing countries. The Developing Economics, 37(2), 222–240.

Bray, M. (2006). Private supplementary tutoring: Comparative perspectives on patterns and implications. Compare: A Journal of Comparative Education, 36(4), 515–530.

Bray, M. (2010). Blurring boundaries: The growing visibility, evolving forms and complex implications of private supplementary tutoring. Orbis Scholae, 4(2), 61–73.

Bray, M., & Bunly, S. (2005). Cambodia: Balancing the books: Household financing of basic education (Working Paper, No. 33810). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Bray, M., & Kwok, P. (2003). Demand for private supplementary tutoring: Conceptual considerations, and socio-economic patterns in Hong Kong. Economics of Education Review, 22, 611–620.

Bray, M., & Silova, I. (2006). The private tutoring phenomenon: International patterns and perspectives. In I. Silova, V. Būdienė, & M. Bray (Eds.), Education in a hidden marketplace: Monitoring of private tutoring (pp. 27–40). New York: Open Society Institute.

Castro, B., & Guzman, A. (2010). Push and pull factors affecting Filipino students’ shadow education (SE) participation. KEDI Journal of Educational Policy, 7(1), 43–66.

Castro, B., & Guzman, A. (2012). From scratch to notch: Understanding private tutoring metamorphosis in the Philippines from the perspectives of cram school and formal school administrators. Education and Urban Society, 2(1), 1–25.

Choi, S., Kim, M., Kim, O., Kim, J., Lee, M., Lee, S., et al. (2003). Managing the private tutoring problem. Seoul: Korean Educational Development Institute (In Korean).

Clogg, C. C., Eva, P., & Adamantios, H. (1995). Statistical methods for comparing regression coefficients between models. American Journal of Sociology, 100, 1261–1293.

Dang, H. (2006). The determinants and impact of private tutoring classes in Vietnam. Economics of Education Review, 26(6), 683–698.

Davies, S., Aurini, J., & Quirke, L. (2002). New markets for private education in Canada. Education Canada, 42, 36–41.

Foondun, A. R. (2002). The issue of private tuition: An analysis of the practice in Mauritius and selected Southeast Asian countries. International Review of Education, 48, 485–515.

Fuller, B., & Clarke, P. (1994). Raising school effects while ignoring culture? Local conditions and the influence of classroom tools, rules, and pedagogy. Review of Educational Research Spring, 64, 119–157.

Hanushek, E. A., Kain, J. F., Rivkin, S. G., & Branch, G. F. (2007). Charter school quality and parental decision making with school choice. Journal of Public Economics, 91, 823–848.

Jeon, S.-I., Kang, I.-W., & Kim, E.-Y. (2003). The relationship between satisfaction with public education and private education attitude. The Korean Journal of Management Education, 30, 176–205 (In Korean).

Jung, J. H., & Lee, K. H. (2010). The determinants of private tutoring participation and attendant expenditures in Korea. Asia Pacific Education Review, 11(2), 159–168.

Kim, M., Kang, Y., Park, S., Lee, H., & Hwang, Y. (2006). Scales of the entrance examination industry and its development: A study of the entrance examination industry and college admission policy. Seoul: Korean Educational Development Institute (In Korean).

Kim, S., & Lee, J. (2010). Private tutoring and demand for education in South Korea. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 58(2), 259–296.

Kim, Y., & Shin, H. (2009). Influence of school characteristics on student academic achievement and analysis of school effect. Paper presented at Symposium on data analysis using the Korea College Scholastic Ability Test and National Assessment of Educational Achievement. Research material. ORM 2009-40. Seoul: Korea Institute of Curriculum and Evaluation (In Korean).

Korean National Statistics Office. (2009). Survey of private education expenditure in 2008. Daejeon: Author.

Lee, J. (2007). Two worlds of private tutoring: The prevalence and causes of after-school mathematics tutoring in Korea and the United States. Teachers College Records, 109(5), 1207–1234.

Lee, C. J., Park, H.-J., & Lee, H. (2009). Shadow education systems. In G. Sykes, B. Schneider, D. N. Plank, & T. G. Ford (Eds.), Handbook of education policy research (pp. 901–919). London: American Educational Research Association, Routledge.

Lockheed, M. E., & Levin, H. M. (2012). Creating effective schools. In H. M. Levin & M. E. Lockheed (Eds.), Effective schools in developing countries (pp. 1–18). New York: Routledge.

NESSE. (2011). The challenge of shadow education: Private tutoring and its implications for policy makers in the European Union. An Independent Report. European Commission.

OECD. (2008). Education at a glance: OECD indicators. Paris: Author.

Park, H.-J. (2010). Quality of school education and participation in private tutoring. In C. Lee (Ed.), Private tutoring: The phenomenon and the response (pp. 317–338). Seoul: Kyoyookkwahaksa (In Korean).

Paviot, L., Heinsohn, N., & Korkman, J. (2008). Extra tuition in southern and eastern Africa: Coverage, growth, and linkages with pupil achievement. International Journal of Educational Development, 28(2), 149–160.

Popa, S., & Acedo, C. (2006). Redefining professionalism: Romanian secondary education teachers and the private tutoring system. International Journal of Educational Development, 26, 98–110.

Rodriguez, M. C. (2004). The role of classroom assessment in student performance on TIMSS. Applied Measurement in Education, 17, 1–24.

Sang, K. A., & Baek, S. G. (2005). Demographic analysis on students’ private tutoring experience. Journal of College of Education, 69, 43–62 (In Korean).

Shin, J., Lee, H., & Kim, Y. (2009). Student and school factors affecting mathematics achievement: International comparisons between Korea, Japan and the USA. School Psychology International, 30, 520–537.

Silova, I. (Ed.). (2009). Private supplementary tutoring in Central Asia: New opportunities and burdens. Paris: UNESCO IIEP.

Silova, I., & Bray, M. (2006a). The hidden marketplace: Private tutoring in former socialist countries. In I. Silova, V. Budiene, & M. Bray (Eds.), Education in a hidden marketplace: Monitoring of private tutoring (pp. 71–98). New York: Open Society Institute.

Silova, I., & Bray, M. (2006b). Implications for policy and practice. In I. Silova, V. Budiene, & M. Bray (Eds.), Education in a hidden marketplace: Monitoring of private tutoring (pp. 71–98). New York: Open Society Institute.

Silova, I., Budiene, V., & Bray, M. (Eds.). (2006). Education in a hidden marketplace: Monitoring of private tutoring. New York: Open Society Institute.

Silova, I., & Kazimzade, E. (2006). Azerbaijan. In I. Silova, V. Būdienė, & M. Bray (Eds.), Education in a hidden marketplace: Monitoring of private tutoring (pp. 71–98). New York: Open Society Institute.

Song, K. (2010). Developmental strategies of public school systems and private tutoring. In C. Lee (Ed.), Private tutoring: The phenomenon and the response (pp. 291–316). Seoul: Kyoyookkwahaksa (In Korean).

Song, K., & Lee, K. (2010). Analysis of relationship among the characteristics of school education and the demand for private tutoring. Paper presented in the 5th conference in the Korean Education and Employment Panel. Seoul: Korea Research Institute for Vocational Education & Training (In Korean).

Stevenson, D., & Baker, D. (1992). Shadow education and allocation in formal schooling: Transition to university in Japan. American Journal of Sociology, 97(6), 1639–1657.

Sue, S., & Okazaki, S. (1990). Asian-American educational achievement: A phenomenon in search of an explanation. American Psychologist, 45, 913–920.

Taiwan Ministry of Education. (1999). Education statistics in the Republic of China. Taipei: Ministry of Education (In Chinese).

Tansel, A., & Bircan, F. (2007). Private supplementary tutoring in Turkey: Recent evidence on its various aspects. Working papers, Turkish Economic Association.

UNESCO. (2000). The EFA 2000 assessment: Country reports—Romania. Paris: UNESCO. Available on www2.unesco.org/wef/countryreports/Romania/rapport_1.html.

Wang, L.-N. (2009). A study of the student participation patterns to private tutoring in Taiwan. Unpublished M. Ed. Dissertation, Seoul National University (In Korean).

World Bank. (1996). Reform of higher education and research project: Report No. 15525-RO. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Zeng, K. (1999). Dragon gate: Competitive examinations and their consequences. London: Cassell.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Song, KO., Park, HJ. & Sang, KA. A cross-national analysis of the student- and school-level factors affecting the demand for private tutoring. Asia Pacific Educ. Rev. 14, 125–139 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-012-9236-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-012-9236-7