Abstract

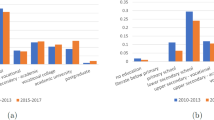

This paper analyzes the dynamics of rate of returns for postgraduate education and the determinants of wage premiums for postgraduate labor, especially for the impact of higher education expansions, in terms of quantity and quality, since the late 1990s in Taiwan. Utilizing quasi-panel data over the 1990–2004 period and employing the double fixed effect model, the empirical results first confirm the existence of wage premiums for workers with postgraduate degrees. However, the analysis on the dynamics of wage premiums finds that it ranged from only 1.40 to 11.67% and decreased sharply in 2004, indicating that the pecuniary reward for postgraduate qualification seems not to be as high as expected. Along with the rapid expansion of higher education, the concern about its negative impact on rate of returns to education is witnessed in this study. The sharp increase in the supply of postgraduate labors appears to have a negative impact on an individual’s wage premium. Similarly, a decline in the postgraduate labor quality along with higher education expansion has contributed to a negative wage effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

If the students who enroll in a masters program in foreign countries are included, the ratio of postgraduates to college/university undergraduates is about 20% in 2006.

There are some (vocational) colleges remaining until now, because they do not meet the standards to transform into four-year universities. However, their recruiting quota of students was cut down by the Ministry of Education year by year.

One alternative reason which caused the increasingly high passing rate is the trend of the lower fertility rate in Taiwan for the last two decades.

In most developed countries, the higher education expansion has been accompanied with differentiation which had consisted almost exclusively of research universities and developed second-tier colleges. However, Taiwan’s higher education expansion is criticized to be homogenized by eliminating the vocational education system.

The parameter can be used to derivate the marginal internal rate of return to additional schooling only depends on a set of assumptions. Concerning these assumptions, please see Bjorklund and Kjellstrom’s (2002) discussions.

According to the definition proposed by the Small and Medium Enterprise Administration, from the Ministry of Economic Affairs of Taiwan, a firm with more than 200 employees is classified as a large enterprise.

The nine occupations include: (1) legislators, government administrators, business executives and managers, (2) professionals, (3) technicians and associate professionals, (4) clerks, (5) service workers and shop and market sales workers, (6) agricultural, animal husbandry, forestry and fishing workers, (7) craft and related trades workers, (8) plant and machine operators and assemblers, and (9) elementary occupations.

The nine industries include: (1) agriculture, forestry, fishing and animal husbandry, (2) mining and quarrying, (3) manufacturing, (4) electricity and gas supply, (5) water supply and remediation services, (6) construction, (7) wholesale and retail trade, (8) transportation and storage, and (9) accommodation and food services.

The estimate on experience variable is probably misleading for women who leave the labor force.

The worst case situation is to spend 3 years to finish the master’s degree, including the thesis.

References

Allen, S. G. (2001). Technology and the wage structure. Journal of Labor Economics, 19, 440–483.

Arias, O., & McMahon, W. W. (2001). Dynamic rates of returns to education in the U.S. Economics of Education Review, 20(2), 121–138.

Bartel, A., & Sicherman, N. (1999). Technological change and wages: An interindustry analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 107(2), 285–325.

Berman, E., Bound, J., & Griliches, Z. (1994). Changes in the demand for skilled labour within U.S. Manufacturing industries: Evidence from the annual survey of manufactures. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109, 367–397.

Bjorklund, A., & Kjellstrom, C. (2002). Estimating the return to investments in education: How useful is the standard mincer equation? Economics of Education Review, 21, 195–210.

Bound, J., & Johnson, G. (1992). Changing in the structure of wages during the 1980’s: An evaluation of alternative explanations. American Economic Review, 82, 371–392.

Card, D. (1999). The causal effect of education on earnings. In O. C. Ashenfelter & D. Card (Eds.), The handbook of labor economics (Vol. 3A, pp. 1801–1863). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Card, D. (2001). Estimating the return to schooling: Progress on some persistent econometric problem. Econometrica, 69(5), 1127–1160.

Card, D., & Lemieux, T. (2001). Can falling supply explain the rising return to college for young men. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 705–746.

Cheidvasser, S., & Benitez-Silva, H. (2007). The educated Russian’s curse: Returns to education in the Russian federation during the 1990s. Labour, 21(1), 1–41.

Chuang, Y., & Chao, C. Y. (2001). Educational choice, wage determination, and rates of return to education in Taiwan. International Advances in Economic Research, 7(4), 479–504.

Dolton, P., & Vignoles, A. (2000). The incidence and effects of overeducation in the U.K. Graduate labor market. Economics of Education Review, 19, 179–198.

Gindling, T. H., Goldfarb, M., & Chang, C. C. (1995). Changing return to education in Taiwan: 1978–1991. World Development, 23(2), 343–356.

Hsu, P. (2004). The changes in college premiums, sex-related wage differentials and the returns to unobserved ability. Taiwan Economic Review, 32(2), 267–291.

Katz, L., & Murphy, M. (1992). Changing in relative wages, 1963–1987: Supply and demand factors. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107, 35–78.

Kler, P. (2005). Graduate overeducation in Australia: A comparison of the mean and objective methods. Education Economics, 13(1), 47–72.

Lau, L. (1986). Models of development: A comparative study of economic growth in South Korea and Taiwan. San Francisco: ICS Press.

Lin, C. H., & Wang, C. H. (2005). The incidence and wage effects of overeducation: The case of Taiwan. Journal of Economic Development, 30(1), 31–47.

Pietro, G. D., & Urwin, P. (2006). Education and skills mismatch in the Italian graduate labour market. Applied Economics, 38(1), 79–93.

Psacharopoulos, G. (1994). Returns to investment in education: A global update. World Development, 22(9), 1325–1343.

Psacharopoulos, G., & Patrions, H. A. (2004). Returns to investment in education: A further update. Education Economics, 12(2), 111–134.

Tang, K. K., & Tseng, Y. P. (2004). Industry-specific human capital, knowledge labour, and industry wage structure in Taiwan. Applied Economics, 36(2), 155–164.

Trostel, P., Walker, I., & Woolley, P. (2002). Estimates of the economic return to schooling for 28 countries. Labour Economics, 9, 1–16.

Walker, I., & Zhu, Y. (2005). The college wage premium, overeducation, and the expansion of higher education in the UK. IZA Discussing Paper No. 1627.

Yang, C. H., & Lin, C. H. (2008). Developing employment effects of innovations—Microeconometric evidence from Taiwan. Developing Economies, 46(2), 109–134.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, CH., Lin, CH.A. & Lin, CR. Dynamics of rate of returns for postgraduate education in Taiwan: the impact of higher education expansion. Asia Pacific Educ. Rev. 12, 359–371 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-010-9132-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-010-9132-y