Abstract

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a widespread condition that accounts for 3 million deaths worldwide annually. Despite being extensive healthcare users, people with COPD (PwCOPD) only spend approximately 1% of their time with a healthcare professional. The rest of the time, they are encouraged to self-manage their condition. To encourage better self-management, Bond Digital Health have created a mobile phone app called COPD.Pal® that helps PwCOPD keep track of their condition. This pilot study aimed to assess the safety, engagement, and early efficacy of the app. 25 PwCOPD were recruited and given COPD.Pal® for 6-weeks. Healthcare usage, self-management knowledge, app engagement, dyspnoea, and health-related quality of life were measured at baseline and at 6-weeks. A feedback questionnaire was also collected at follow-up. T-tests investigated whether differences between the time points were evident in the data. No statistically significant differences were found between the time points for any of the variables measured. Average app engagement was 31.8 days with 84% using COPD.Pal® for 20 or more days during the 6-weeks. 89% of participants stated they would use the app regularly after the study, with 56% stating they’d use it long-term. This study determined that a digital, self-management app would be engaged with and early results indicate that the safety is non-inferior to standard care. Although self-management knowledge remained unaffected by app use, this study provided useful insights regarding how to improve this aspect. This represents one of few studies which involve end-users at an early stage of intervention development, an important strength of the research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

With 210 million people diagnosed and three million annual deaths, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a global problem [1]. People with COPD (PwCOPD) have daily symptoms, including dyspnoea, sputum production and coughing, in addition to a poorer health status, reduced exercise capacity, and impairment in lung function [2,3,4]. Furthermore, anxiety and depression are common comorbidities [5, 6]. Symptoms can become worse (above the day-to-day variation) during an acute exacerbation, commonly caused by infection or pollution. Exacerbations of COPD are the second most common cause of emergency admission in the UK, being responsible for one in eight (130 000) of the total, 1 million bed days, and a National Health Service (NHS) expenditure of over £500m in 2015 [2].

Despite PwCOPD being extensive users of the NHS [7, 8], approximately only 1% of their time is spent with healthcare professionals [9]. The rest of the time, PwCOPD are encouraged to self-manage their condition. Relevant self-management behaviours include regular exercise, taking medication, being aware of symptoms, and attending healthcare appointments [2]. Effective self-management interventions have been associated with reduced hospital admissions and an average cost-saving of £671.59 per person [10, 11]. As a result, supporting self-management behaviours has been highlighted as crucial for the care of PwCOPD [12]. However, despite these positive results, it is still important to ensure that new interventions (especially technological ones) do not compromise safety and studies promoting new methods of working should always investigate this aspect as studies have done previously [13, 14].

Despite the positive association between self-management and health outcomes [15], these behaviours are seldom taught, and rarely followed over prolonged periods [16]. This is illustrated by examining pulmonary rehabilitation (a multidisciplinary disease management course for PwCOPD) attendance and adherence rates. The most recent UK national audit found that of those who are invited to pulmonary rehabilitation, only 69% attend the initial assessment and 42% complete the course [17, 18]. Studies investigating why PwCOPD do not engage in self-management behaviours have found a range of factors, including low motivation and a lack of emphasis on behavioural change [16, 19].

To enable PwCOPD to have a greater awareness of symptom changes, a digital, self-management app called COPD.Pal® was developed in partnership with Bond Digital Health Ltd. (BDH; Cardiff, UK; https://bondhealth.co.uk/) using a person-centred approach [20, 21]. COPD.Pal® enables PwCOPD to log symptoms, wellness, and medications, with an aim that through the storing of this data, self-management, illness understanding, and confidence can be improved. Initial qualitative analyses demonstrate that this app is usable and acceptable to PwCOPD [21]; however, further research is needed to quantitatively evaluate safety and user engagement. Therefore, this research study was conducted to answer the research question: ‘Is a self-management, mobile phone app safe and do PwCOPD engage?’. The study also collected self-management knowledge data to begin investigating early efficacy of the app.

2 Methods

This study was a quantitative, single-arm, clinical pilot study designed to evaluate the safety and user engagement of COPD.Pal®. Participants completed baseline and six week, follow-up questionnaires using COPD.Pal® in between these time points. The study was approved by a Research Ethics Committee (19/WA/0347) and local research and development governance and is registered online (ISRCTN: 14530045).

2.1 Participants

PwCOPD were recruited between 20th January and 11th February 2020 from Hywel Dda University Health Board, Wales. To be eligible, prospective participants had to have a clinical diagnosis of COPD as defined by GOLD [3]; 40 years old or more, 10 pack years smoking history, and spirometry ratio of 0.7 with less than 80% predicted. Those that had a cognitive, visual, or motor impairment that would prevent them using a smart phone, or were a current hospital inpatient, were not eligible.

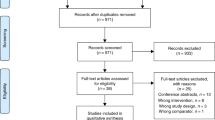

A total of 71 PwCOPD were invited to participate with 25 being recruited by giving written informed consent. Nineteen were male, the mean age was 64 (standard deviation [SD] = 7.71), pack year smoking history was 37.9 (SD = 18.6), and FEV1 was 49% (SD = 19.3%).

2.2 The COPD.Pal® intervention

For this study, all participants were provided with a mobile smart phone with the COPD.Pal® app already installed. A member of the research team guided the participant through the set-up process and then answered any questions. Participants were asked to use COPD.Pal® for six weeks; however, no lifestyle restrictions were implemented and PwCOPD were invited to use the app as they would use others.

COPD.Pal® collects a range of data from questionnaires, asked at different frequencies. This includes the modified Medical Research Council Dyspnoea scale (mMRC) [22] and the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) [23], which measure dyspnoea and health-related quality of life (HRQoL), respectively.

2.3 Data collection

Engagement with COPD.Pal® was collected automatically via the app. Outside of the app, data was collected at baseline and a 6-week follow-up. This included COPD self-management knowledge and confidence, as assessed by the Understanding COPD questionnaire (UCOPD) [24], number of exacerbations over the past three months, hospital and General Practitioner (GP) attendances (due to COPD), and use of steroids. Follow-up data collection asked participants to report the same measures but since they started using COPD.Pal®. Additionally, a feedback questionnaire, containing Likert and free-text boxes (see Supplementary file 1), measuring usability and acceptability was completed at follow-up.

2.4 Analysis

Related t-tests were used to investigate whether there were differences between baseline and follow-up for the variables of HRQoL, dyspnoea, healthcare usage (i.e. exacerbations, hospitalisations, etc.), and self-management knowledge. COPD.Pal® engagement was calculated from the app as number of days out of the maximum (i.e. 6 weeks or 42 days). Percentage of positives scores were calculated from the Likert section of the feedback questionnaire. Common themes were identified from the free-text section of the feedback questionnaire and summarised.

3 Results

Participant data was collected through research questionnaires and the COPD.Pal® app. The research questionnaires were collected at baseline and 6-weeks. COPD.Pal® data was collected automatically at set time points. Table 1 shows baseline and follow-up data for the participants.

On average, participants used the app for 31.8 (SD = 10.9) days out of 42 days, with 84% using COPD.Pal® for 20 or more times over the study period.

No participants had any adverse events whilst using COPD.Pal®. Although hospitalisations, GP appointments, and antibiotic- and steroid-use reduced during the study, these differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.83, 95% confidence intervals [CI] = -0.02-0.26; p = 0.16, 95% CI = -0.07-0.39; p = 0.13, 95% CI = -0.11-0.75; p = 0.33, 95% CI = -0.13-0.38, respectively). Similarly, there were no statistically significant differences in HRQoL (p = 0.26, 95% CI = -3.63-1.02) or dyspnoea scores (p = 0.74, 95% CI = -0.65-0.47).

No statistically significant differences were detected between baseline and follow-up self-management knowledge and confidence scores, either for Knowledge of COPD (p = 0.21, 95% CI = -8.0-1.82), Ability to manage symptoms (p = 0.22, 95% CI = -8.9-2.18), Knowledge of ways to access help and support (p = 0.76, 95% CI = -7.09-9.65), or overall (p = 0.29, 95% CI = -6.45-2.01).

The feedback questionnaire completed at the end of the 6-week period found that 89% of participants stated that they would use the app regularly, 61% found it useful, and 56% would use it long-term. Six people, however, did report technical difficulties with the mobile phones that were supplied as part of this study and this may have negatively affected scores.

The main themes within the free-text boxes on the feedback questionnaire regarded the repetitive nature of the questions, where participants described the same items being asked each day regardless of previous scores. Additionally, no detailed feedback was provided based upon these scores that limited the extent to which participants could learn from the information they had inputted. Lastly, participants believed that the app should include questions which relate to the holistic nature of COPD, providing opportunity to input information on how they felt both physically and mentally.

4 Discussion

This study aimed to understand whether a digital, self-management app was safe and if PwCOPD would use it, whilst also beginning to collect and analyse data regarding the efficacy of COPD.Pal®.

Participants experienced no adverse events during the study and several variables actually showed more beneficial states at follow-up, albeit not to a statistically significant degree. Although this study includes a relatively small sample size, the lack of differences between the two time points does begin to indicate that the use of COPD.Pal® is non-inferior to the safety that standard care provides. Self-management interventions have been associated with reduced hospitalisations [11] and future research could investigate whether self-management apps replicate similar findings, in addition to reductions in GP appointments and medication usage (as findings suggest here). Previous literature has found that per-person medication costs for PwCOPD were, on average, between £328 and £954 per annum [25, 26]. Therefore, given the high prevalence of COPD, if effective self-management can reduce unnecessary medication usage, apps like COPD.Pal® could be associated with significant cost-savings.

Over 80% of participants used the app regularly and 56% stated they would use the app long-term if they were given the opportunity. This was despite several technical issues with the mobile phone handsets that were provided as part of the study. These results indicate that PwCOPD would use a digital, self-management app; however, participants indicated they were dissatisfied with the feedback they were provided and the limited selection of questionnaires that were available to answer daily. This feedback provides useful suggestions that can be easily addressed at this stage of technology development and increase engagement further; highlighting the importance of including end-users within early-development of these interventions [20], which is unfortunately lacking in most chronic healthcare interventions. Moreover, at this stage, COPD.Pal® does not incorporate any major psychological theory to help foster engagement, because selecting an appropriate theory was delayed to enable the consideration of initial testing (i.e. this study and a previous one; [21]. Use of such theories has widely been reported to increase long-term adherence [20, 27, 28]; therefore, the relatively high initial engagement demonstrated in this study could be increased further in future iterations of the app.

The aim of COPD.Pal® is to foster improved self-management and confidence through providing PwCOPD an accurate method of tracking daily symptom fluctuations. To begin to test the early efficacy of the app, the UCOPD questionnaire was used to measure self-management knowledge. No statistically significant differences were found between the time points and therefore, in its current iteration, COPD.Pal® does not increase self-management knowledge; however, 61% of participants did find the app useful. It is important to note that this study was not statistically powered to find significant differences in the UCOPD variable and baseline scores show relatively high levels of self-management knowledge (thus making it unlikely for possible differences to be found in small samples). One exception to the high levels found is the average score for ‘knowledge of ways to access help and support’. Previous research conducted by the authors (unpublished) has also identified a relatively low score in this sub-scale and future research should be conducted to investigate the prevalence, impact, and solutions to overcome this deleterious finding. Interestingly, supporting self-management was a topic for which participants provided feedback, indicating that they wished to receive more information regarding the scores they entered into the app. Thus, it is possible that by incorporating methods to provide users with tailored information regarding their condition, self-management knowledge could be increased in future iterations. Previous research conducted on COPD.Pal® has also suggested that by including this feedback function, perceived usefulness of the app could be increased and, through this, benefits for adherence [21]. The want for tailored feedback also does strengthen the findings of the qualitative analysis of COPD.Pal® [21], which described how participants’ suggestions could be explained through the use of self-determination theory, particularly the concept of autonomy [29]. Future studies should investigate whether self-determination theory constructs may be beneficial in predicting important healthcare and research outcomes.

The main strength of this study is that it has recruited end-users at an early stage of app development and thus responds to recommendations provided to support the creation of digital interventions [20]. Although only including a small sample size, this study, alongside a previous qualitative one [21], has provided useful information to inform the development of COPD.Pal® and future research projects. A limitation of the study is that, although it included a questionnaire to measure self-management knowledge, it didn’t measure the actual number of self-management activities in which the participant engaged. This was primarily because of the large range of relevant activities involved in COPD self-management (e.g. regular exercise, taking medication, attending appointments) [2] made it impractical to include a questionnaire that measured all of them. Nevertheless, future research could overcome this limitation by asking participants for the number of self-management activities they conduct.

In conclusion, although this study represents the early testing of a self-management app, the results indicate that COPD.Pal® is non-inferior to the safety that standard care provides. The app enables PwCOPD to track their symptoms and participants are willing to engage over the short-term, with the majority indicating this would be continued long-term. Although no statistically significant differences were detected within this study for self-management knowledge, participants provided useful suggestions for how this aspect could be improved in future versions of the app. This represents important information collected near the beginning of development and highlights the need for more interventions to incorporate end-users throughout early testing of healthcare interventions. After responding to feedback obtained from this study, further research should be conducted to investigate the effectiveness of COPD.Pal® to empower PwCOPD to self-manage their condition. Such research should be fully statistically powered and could incorporate mixed-methodology into one study, to fully explore the app’s ability to positively impact healthcare usage, self-management knowledge, and facilitate communication between those with the condition and healthcare professionals.

Data availability statement

Unfortunately, the authors did not ask participants to provide consent for their data to be stored in an openly accessible online repository and therefore research data for this study is not shared. However, the authors invite any and all questions regarding data, which they will provide as much information as possible covered by the consent provided by participants already

References

Quaderi SA, Hurst JR. The unmet global burden of COPD. Glob Health Epidemiol Genom. 2018;3:e4.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management. 2018.

Singh D, Agusti A, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, Celli BR, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease: the GOLD science committee report 2019. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(5).

World Health Organisation. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). 2016.

Khan S, Patil B. Risk of depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its determinants. Indian Journal of Health Sciences and Biomedical Research (KLEU). 2017;10(2):110–5.

Phan T, Carter O, Waterer G, Chung LP, Hawkins M, Rudd C, et al. Determinants for concomitant anxiety and depression in people living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Psychosom Res. 2019;120:60–5.

Department of Health. An outcomes strategy for COPD and asthma: NHS companion document. 2012.

Dhamane AD, Moretz C, Zhou Y, Burslem K, Saverno K, Jain G, et al. COPD exacerbation frequency and its association with health care resource utilization and costs. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2609–18.

National Health Service England. Five Year Forward View. 2014.

Khdour MR, Agus AM, Kidney JC, Smyth BM, Elnay JC, Crealey GE. Cost-utility analysis of a pharmacy-led self-management programme for patients with COPD. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(4):665–73.

Zwerink M, Brusse-Keizer M, van der Valk PD, Zielhuis GA, Monninkhof EM, van der Palen J, et al. Self management for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014(3):Cd002990.

Kielmann T, Huby G, Powell A, Sheikh A, Price D, Williams S, et al. From support to boundary: a qualitative study of the border between self-care and professional care. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79(1):55–61.

Fan VS, Gaziano JM, Lew R, Bourbeau J, Adams SG, Leatherman S, et al. A comprehensive care management program to prevent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalizations: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(10):673–83.

Knox L, Dunning M, Davies C-A, Mills-Bennet R, Sion TW, Phipps K, et al. Safety, feasibility, and effectiveness of virtual pulmonary rehabilitation in the real world. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:775–80.

Benzo RP, Abascal-Bolado B, Dulohery MM. Self-management and quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): The mediating effects of positive affect. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(4):617–23.

Russell S, Ogunbayo O, Newham J, Heslop-Marshall K, Netts P, Hanratty B, et al. Qualitative systematic review of barriers and facilitators to self-management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Views of patients and healthcare professionals. NPJ Prim Care Resp Med. 2018;28.

Steiner M, Holzhauer-Barrie J, Lowe D, Searle L, Skipper E, Welham S, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation: time to breathe better. National Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) audit programme: resources and organisation of pulmonary rehabilitation services in England and Wales. 2015.

Steiner M, Holzhauer-Barrie J, Lowe D, Searle L, Skipper E, Welham S, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation: steps to breathe better. National chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) audit programme: clinical audit of pulmonary rehabilitation services in England and Wales 2015. National clinical audit report. 2016.

Hillebregt CF, Vlonk AJ, Bruijnzeels MA, van Schayck OC, Chavannes NH. Barriers and facilitators influencing self-management among COPD patients: a mixed methods exploration in primary and affiliated specialist care. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;12:123–33.

Yardley L, Morrison L, Bradbury K, Muller I. The person-based approach to intervention development: application to digital health-related behavior change interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(1):e30-e.

Knox L, Gemine R, Rees S, Bowen S, Groom P, Taylor D, et al. Using the Technology Acceptance Model to conceptualise experiences of the usability and acceptability of a self-management app (COPD.Pal®) for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Health & Technol. 2021;11(1):111–7.

Bestall J, Paul E, Garrod R, Garnham R, Jones P, Wedzicha J. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1999;54(7):581–6.

Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, Wiklund I, Chen WH, Kline Leidy N. Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. Eur Respir J. 2009;34(3):648–54.

O’Neill B, Cosgrove D, MacMahon J, McCrum-Gardner E, Bradley JM. Assessing education in pulmonary rehabilitation: the Understanding COPD (UCOPD) questionnaire. Copd. 2012;9(2):166–74.

Tavakoli H, Johnson KM, FitzGerald JM, Sin DD, Gershon AS, Kendzerska T, et al. Trends in prescriptions and costs of inhaled medications in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a 19-year population-based study from Canada. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:2003–13.

Lange P, Jakobsen M, Anker N, Dollerup J, Poulsen PB. The drug costs associated with COPD prescription medicine in Denmark. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(Suppl 56):P1293.

Yardley L, Williams S, Bradbury K, Garip G, Renouf S, Ware L, et al. Integrating user perspectives into the development of a web-based weight management intervention. Clin Obes. 2012;2(5–6):132–41.

Prestwich A, Sniehotta FF, Whittington C, Dombrowski SU, Rogers L, Michie S. Does theory influence the effectiveness of health behavior interventions? Meta-analysis Health Psychol. 2014;33(5):465–74.

Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior 1985.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the participants for giving up their time to take part in this research study, in addition to the Welsh Government for funding the project.

Funding

This work was supported by the Welsh Government’s Efficiency through Technology Programme [grant number 51/2017].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

KL, PG, DT, and IB own shares in Bond Digital Health Ltd., the creators of COPD.Pal®, and were involved in designing the study but were not involved in the data collection or analysis.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was received by the National Health Services Research Ethics Committee (19/WA/0347). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

All participants gave fully informed consent to participate in this study before taking part in any research activities

Consent to publication

All participants provided their consent for anonymised data and quotes to be used in the publication of the results of the study

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Knox, L., Gemine, R., Rees, S. et al. Assessing the uptake, engagement, and safety of a self-management app, COPD.Pal®, for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: a pilot study. Health Technol. 11, 557–562 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12553-021-00534-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12553-021-00534-w