Abstract

Several hundred isolated anuran bones recovered from 37 localities in southern Utah, USA, provide a relatively continuous record of the evolution of anuran assemblages in the central part of the North American Western Interior that spans almost 25 million years, from the early Cenomanian to the late Campanian. Although it is difficult to associate isolated anuran bones from different parts of the skeleton with each other, it is possible to identify distinctive morphs for certain bones (e.g., ilia, maxillae) that can be used to make inferences about the taxonomic diversity of fossil assemblages. Because the samples document a relatively long interval of time, they can also be used to recognize trends in the anatomical evolution of anurans and in the evolution of anuran assemblages. Small-bodied anurans prevailed until the early Campanian, then beginning in the late Campanian, larger-bodied anurans began dominating assemblages. Using iliac morphs as a proxy for taxonomic diversity, it is apparent that some local assemblages were surprisingly diverse. When coupled with previously reported fossils, the new specimens from Utah help document when certain anatomical features appeared and radiated among anurans. Ilia in the majority of early anurans (including the earliest anuran Prosalirus) had an oblique groove on the dorsal margin but lacked a dorsal tubercle. Through the Late Cretaceous, there is a trend towards an increasing majority of ilia having a well-developed dorsal tubercle; this osteological change could be associated with changes in locomotor behavior. Procoelous vertebrae are already present in the Cenomanian samples, which indicates that this derived anuran vertebral condition must have appeared before the Late Cretaceous.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Mesozoic record of anurans in North America consists of three-dimensionally preserved, disarticulated and rare semi-articulated bones. Except for one occurrence each in New Jersey and Baja California, the North American Mesozoic anuran record is geographically limited to the Western Interior of the USA, from Texas north to Montana and North Dakota, and into southern Alberta and Saskatchewan, Canada. This record is also stratigraphically patchy, with occurrences in the middle Early Jurassic (Pliensbachian), in the late Late Jurassic (Kimmerdgian, ?Tithonian), and then a relatively continuous sequence from the late Early Cretaceous to the K/T boundary (latest Aptian/early Albian–Maastrichtian). The Mesozoic record of frogs in Utah extends from the Early/Late Cretaceous boundary to the end of the Maastrichtian. In an attempt to put the Utah record into context, below we briefly review the Mesozoic record of North American anurans.

The geologically oldest anuran fossils from anywhere in the world date from the Early Jurassic (Pliensbachian) of North America. At the Gold Springs Quarry in the Kayenta Formation of northeastern Arizona, hand quarrying produced three silty slabs that contain the mostly disarticulated skull and postcranial bones from several individuals (Shubin and Jenkins 1995; Jenkins and Shubin 1998), and subsequent screen-washing of the spoil pile produced an isolated humerus and five ilia (Curtis and Padian 1999). The quarried specimens were described as belonging to Prosalirus bitis Shubin and Jenkins, 1995, whereas the screen-washed specimens were identified by Curtis and Padian (1999: 23) only as "Anura". Sufficient material of Prosalirus is available to permit a partial reconstruction of the skeleton (Shubin and Jenkins 1995: Fig. 3a, d) and to demonstrate that it is a basal anuran, although its exact position relative to other basal anurans is uncertain (e.g., Gao and Wang 2001; Borsuk-Białynicka and Evans 2002). Some of the bones from Gold Springs Quarry (especially the premaxilla, maxilla, vertebrae, urostyle, scapula, and ilium) can be used for comparisons with anuran bones from younger North American Mesozoic localities.

The next oldest occurrences are from the Late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian–?Tithonian), from two localities in the upper part of the Morrison Formation: Como Bluff in Wyoming and the Rainbow Park Microsite in Utah. Eobatrachus agilis Marsh, 1887 (see also Moodie 1912, 1914) and Comobatrachus aenigmaticus Hecht and Estes, 1960, were both named for partial humeri from Como Bluff; neither taxon is currently accepted (e.g., Estes and Sanchíz 1982; Evans and Milner 1993; Henrici 1998a, b). Sanchíz (1998) considered both of them nomina vana. An incomplete ilium from Como Bluff was assigned by Evans and Milner (1993) to the Pelobatidae sensu lato, but J.-C. Rage (pers. comm. in Roček 2000: 1302) suggested it may instead be referable to the Discoglossidae sensu lato. Enneabatrachus hechti Evans and Milner, 1993 is known by an incomplete ilium (holotype) from Como Bluff (Evans and Milner 1993) and by an urostyle and an incomplete skeleton from the Rainbow Park Microsite (Henrici 1998b); most workers (e.g., Evans and Milner 1993; Henrici 1998a, b; Sanchíz 1998; Roček 2000; Holman 2003) include Enneabatrachus within the Discoglossidae sensu lato. Henrici (1998a) described Rhadinosteus parvus based on nine incomplete skeletons and some isolated bones, from metamorphosing larvae to young postmetamorphic individuals, that are preserved on mudstone slabs from the Rainbow Park Microsite. Henrici (1998a) interpreted Rhadinosteus as a member of the Pipoidea, which makes it the earliest record for that clade, and possibly a member of the Rhinophrynidae. Finally, based on distinctive ilia from the Rainbow Park Microsite, Henrici (1998b) also reported a possible discoglossid sensu lato and two indeterminate genera and species.

The oldest Cretaceous anuran fossils are isolated skull and postcranial bones from about a dozen localities of late Aptian–middle Albian age (Winkler et al. 1990; Cifelli et al. 1997) in the following units of the Trinity Group: the upper and middle parts of the Antlers Formation in, respectively, northcentral Texas (e.g., Zangerl and Denison 1950; Hecht 1963; Winkler et al. 1990; Gardner 1995) and southeastern Oklahoma (Cifelli et al. 1997) and the Twin Mountains and Paluxy formations in central Texas (Winkler et al. 1989, 1990). Specimens from the Antlers Formation have not been formally described. Based on the ornamentation of skull bones from the Antlers Formation of northcentral Texas, Hecht (1963) suggested those might be referable to the Leptodactylidae sensu lato, but this identification was questioned by Lynch (1971) in his monographic treatment of that family. Winkler et al. (1990) described a small number of isolated bones from several localities in central Texas. Those authors tentatively assigned a humerus and urostyle, both from the Twin Mountains Formation, and a sacral vertebra from the Paluxy Formation to the Discoglossidae sensu lato and regarded the remaining specimens (maxillae from both formations; vertebrae and tibiofibulae from the Paluxy Formation) as being from indeterminate anurans. Based on Winkler et al’s (1990) published account of the central Texas specimens, Roček and Nessov (1993) and Roček (2000) suggested that the maxillae and vertebrae might pertain to the Gobiatidae, which otherwise are known only from the Late Cretaceous of Central Asia (e.g., Roček and Nessov 1993; Roček, 2000, 2008).

The next youngest North American anurans are of latest Albian–earliest Cenomanian age, and are known by isolated bones and several incomplete, partially articulated skeletons from the uppermost part of the Cedar Mountain Formation in central Utah (Gardner 1995; Cifelli et al. 1999a). Slightly younger anurans have been reported (Winkler and Jacobs 2002) from the middle Cenomanian Woodbine Formation of Texas. Specimens from both formations have yet to be formally described.

Intensive screen-washing programs over the past 25 years in southern Utah have yielded hundreds of anuran bones from a statigraphically extensive series of localities in the Dakota Formation (Cenomanian), the Smoky Hollow (Turonian) and John Henry (Coniacian–Santonian) members of the Straight Cliffs Formation, the Wahweap (middle Campanian), Iron Springs Formation (Santonian or Campanian), and Kaiparowits Formation (late Campanian) (e.g., Eaton et al. 1999a, b; Gardner et al. 2009). The first detailed report on these collections is contained in the main part of this paper.

All but one of the remaining Late Cretaceous anuran records in North America are from outside Utah and most of these consist of isolated skull and postcranial bones. The oldest of these occurrences is in the Deadhorse Coulee Member (late Santonian) in the upper part of the Milk River Formation of southeastern Alberta (Fox 1972, 1976b). Anurans are next known from the following seven units of middle–late Campanian age: Aguja Formation in Texas (Rowe et al. 1992); "Mesaverde" Formation in Wyoming (Breithaupt 1985; DeMar and Breithaupt 2006, 2008); Judith River Formation in Montana (Sahni 1972; Blob et al. 2001); Foremost, Oldman, and Dinosaur Park formations in Alberta (Fox 1976b; Brinkman 1990; Gardner 2000, 2005; Peng et al. 2001; Eberth et al. 2001); and Dinosaur Park Formation in Saskachewan (Eberth et al. 1990). Regarding specimens from the Judith River Formation of Montana, Sahni (1972) recognized several morphs of maxillae, ilia, and humeri that he assigned to the Discoglossidae sensu lato and Pelobatidae sensu lato, and Blob et al. (2001) reported on three unusual ilia that they described as belonging to a new anuran taxon, Nezpercius dodsoni. Gardner (2000, 2005) provisionally recognized two new, but unnamed anuran taxa from the Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta. The next youngest anuran fossils are rare, isolated bones from the late Campanian Fruitland Formation of New Mexico (Armstrong-Ziegler 1980; Hunt and Lucas 1993) and from the late Campanian–early Maastrichtian Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta (Eberth et al. 2001; Gardner 2005; Larson et al. in press). There are two reports of North American Campanian anurans from outside of the Western Interior: in the "El Gallo Formation" of Baja California (Lillegraven 1976; Estes and Sanchíz 1982) and in the Marshalltown Formation of New Jersey (Denton and O’Neill 1998).

The youngest North American Mesozoic anurans are from the late Maastrichtian. Anurans of this age have been reported from the Frenchman Formation in Saskatchewan (Fox 1989; Tokaryk 1997), the lower part of the Scollard Formation in Alberta (Eberth et al. 2001), and the lower part of the North Horn Formation in Utah (Cifelli et al. 1999b), but are best known from the Lance Formation in Wyoming (Estes 1964, 1969, 1970; Fox 1976a; Breithaupt 1982, 1985; Estes and Sanchíz 1982) and the Hell Creek Formation in Montana and North Dakota (Estes 1969; Estes et al. 1969; Estes and Sanchíz 1982; Bryant 1989; Pearson et al. 2002). The Bug Creek Anthills locality in the upper part of the Hell Creek Formation in Montana has produced numerous anuran bones—including the holotype of Scotiophryne pustulosa Estes, 1969—and initially was considered to be late Maastrichtian in age (e.g., Estes 1964, 1969, 1970; Estes et al. 1969; Fox 1976b; Breithaupt 1982, 1985; Estes and Sanchíz 1982; Bryant 1989; Sanchíz 1998; Gardner 2000; Holman 2003). This locality is now interpreted as containing a mix of lowermost Paleocene and reworked upper Maastrichtian fossils (Lofgren 1995; Cifelli et al. 2004; Kielan-Jaworowska et al. 2004). Fortunately, all the anuran taxa known from the Bug Creek Anthills also occur in the Lance Formation, which is unquestionably late Maastrichtian in age. Additionally, thanks to intensive collecting efforts over the past decade, numerous anuran-bearing localities have been identified in unreworked portions of the Hell Creek Formation (e.g., Pearson et al. 2002). Until recently, five anuran species in three families were recognized from the Lance and Hell Creek formations: the palaeobatrachid Palaeobatrachus? occidentalis Estes and Sanchíz, 1982; the discoglossids sensu lato Scotiophryne pustulosa Estes, 1969 and Paradiscoglossus americanus Estes and Sanchíz, 1982; an unidentified species of the pelobatid sensu lato Eopelobates; and the incertae sedis taxon Theatonius lancensis Fox, 1976a (Estes 1964, 1969, 1970; Estes et al. 1969; Fox 1976a; Estes and Sanchíz 1982; Breithaupt 1982, 1985; Bryant 1989; Holman 2003). In the most recent treatment of anurans from the Lance and Hell Creek formations, Gardner (2008) accepted the same five species, but argued that Scotiophryne, Paradiscoglossus, and the Eopelobates-like species could not be assigned to any known family and noted that previous reports of Scotiophryne and Theatonius (Armstrong-Ziegler 1980; Estes and Sanchíz 1982; Breithaupt 1985; Fox 1989; Hunt and Lucas 1993; Denton and O'Neill 1998) in geologically younger formations could not be substantiated. Based on the presence in the Lance Formation of five distinctive maxillary morphs and two distinctive iliac morphs, none of which could be associated with one another or with any of the previously recognized taxa, Gardner (2008) also suggested that the diversity of anurans in that unit might be much higher than previously thought, with perhaps as many as 12 taxa.

Here, we report on several hundred isolated anuran bones recovered from 37 localities in southern Utah. These fossils document a relatively continuous record of the evolution of anuran assemblages in the central part of the North American Western Interior that spans almost 25 million years, from the early Cenomanian to the late Campanian. Other than para-contemporaneous localities in Central Asia (e.g., Roček and Nessov 1993), the Utah sequence contains the earliest records of locally diversified Late Cretaceous anuran assemblages. Although we suspect that certain of the specimens reported herein pertain to distinct taxa, we refrain from formally erecting any new anuran genera or species for two reasons. First, it is difficult to reliably associate isolated anuran bones, especially ones from different parts of the skeleton—for example, skull bones with ilia or vertebrae. Second, because some elements bear peculiar anatomical features not found in contemporary anurans (e.g. maxillae of Theatonius have a longitudinal canal in the interior of their orbital margin), it would be difficult to assign them to any recognized family. Instead, we employ a more typological approach that identifies and describes distinctive morphs for each of the bones. Some of these bones (e.g., maxillae, prearticulars, humeri, ilia, and urostyles) can, however, provide limited taxonomic information. Where appropriate, we use that information as a guide for estimating taxonomic diversities. Finally, because our samples document a relatively long interval of time, we also attempt to recognize some trends in the anatomical evolution of anurans during the Late Cretaceous.

Localities, their ages, geological setting, and depositional environments

A wide geographic (Fig. 1) and stratigraphic (Fig. 2, Table 1) range of localities have produced specimens of anurans that span almost 25 million years of anuran evolution in the Late Cretaceous. The justifications for ages and some information on the deposition environments of localities are provided below, organized by formation in ascending order (with the exception of the Iron Springs Formation, see below). The timescale of Gradstein et al. (2004) is used here. Detailed locality data is available to qualified researchers from the Utah Museum of Natural History, Salt Lake City.

Approximate stratigraphic position and correlation of localities. M.P. Markagunt Plateau, P.P. Paunsaugunt Plateau, K.P. Kaiparowits Plateau (see Fig. 1), CS Capping Sandstone Member of the Wahweap Formation. All except MNA 1004 are UMNH VP localities

The geologic setting in which the anuran-containing strata were deposited is a foreland basin that developed east of the Sevier orogenic fold and thrust belt. This rapidly subsiding basin had high sedimentary rates (e.g., Jinnah et al. 2008) and there was no opportunity for significant reworking of older specimens; in any case, the available source rocks are largely marine and Paleozoic and, thus, would not contain any anuran fossils. The frogs recovered from these rocks are mostly tiny and their bones very delicate, so it is unlikely there was significant transport of these specimens. Many of the localities are in mudstones that contain complete ostracods and gastropods, suggesting little transport of specimens, if any at all. Most of these localities represent riparian to floodplain habitats; relatively rare pond deposits also occur. A few of the localities (particularly from the Dakota Formation, see below) consist of sandy stream lags and proximal overbank deposits and in these cases there may be more extensive habitat mixing. There are inherent limitations in palaeoecologic interpretation and faunal comparisons when considering time-averaged localities that resulted from different taphonomic processes (e.g., Wilson 2008).

Iron Springs Formation

The Iron Springs Formation is present on the Markagunt Plateau in Parowan Canyon and to the west in the Pine Valley Mountains (Fig. 1). The currently known age range of the 1,000-m-thick formation is from the late Albian [based on a 40Ar-39Ar date of 101.7 ± 0.42 Ma (million years ago) in Dyman et al. 2002] to the Campanian (based on a 40Ar-39Ar date of 83.0 ± 1.1 Ma from Eaton et al. 1999b, earliest Campanian, a date recovered from a biotite ash 213 m below the top of the formation in Parowan Canyon; see Eaton et al. 2001). The single locality from the Iron Springs Formation that has produced anurans is UMNH Locality 12 (MNA 1230). This locality is not shown in Fig. 2 because it is the only Iron Springs locality included here and its absolute stratigraphic position is unknown. The locality is a dark mudstone very high in the Iron Springs Formation. In this area, the Iron Springs is unconformably overlain by the Eocene Claron Formation, but there is no way to be certain of how much Iron Springs strata has been removed by erosion during the approximately 20 million years represented by the unconformity. In Parowan Canyon, the Iron Springs Formation is also unconformably overlain the Claron Formation and an earliest Campanian radiometric date (83.0 ± 1.1 Ma; Eaton et al. 1999b) occurs 213 m below the contact. For this reason, but with caution, we consider the age of Locality 12 to be early Campanian, perhaps a little older than faunas recovered from the Wahweap Formation.

Dakota Formation

All vertebrate nonmarine fossils were recovered from the middle member of the Dakota Formation. The upper member is well dated as late Cenomanian based on ammonites (Cobban 1984; Tibert et al. 2003). As the middle member becomes increasing brackish up-section reflecting the rapid transgression of the Western Interior Seaway it seems likely that the middle member is also late Cenomanian, or at oldest, middle Cenomanian. Kowallis et al. (1989) provided 40Ar-39Ar dates from low in the overlying Tropic Shale of 94.7 ± 0.2 Ma and 94.5 ± 0.1 Ma, which would suggest that the upper member of the Dakota Formation is late Cenomanian. Bohor et al. (1991) had reported a 40Ar-39Ar date from the base of the formation of 92.9 ± 0.2 Ma and 90.5 ± from near the top of the formation, but these ages would place the Dakota Formation in the Turonian and such a date is not possible based on ammonites in the upper member. Dyman et al. (2002) also considered the upper member to be of late Cenomanian age, and published a 40Ar-39Ar date of 96.06 ± 0.30 Ma date for the middle member which would place the middle member in the late early Cenomanian. Eaton (personal observation) examined the horizon that was sampled by Dyman et al. (2002) and concluded that the rock is not an airfall ash but a bentonitic mudstone; this casts doubt on the late early Cenomanian age reported by Dyman et al. (2002).

The lower member of the Dakota Formation is a conglomerate that rests unconformably on Jurassic rocks. The middle member is relatively thick, up to 50 m on the Kaiparowits Plateau (Bulldog Bench, where both Kaiparowits Plateau localities are located), and was probably deposited in a relatively brief period of time (~1 million years, the middle and late Cenomanian together only span a little over 2 million years; Gradstein et al. 2004). As such, sedimentary rates were relatively high and there is no evidence of extensively reworked materials. Specimens recovered from UMNH Locality 27 (MNA 1067) clearly underwent some transport as the locality represents overbank fill adjacent to a levee. Specimens from UMNH Locality 804 (MNA 1064) also underwent some transport as they were recovered from a channel lag. Similarly, UMNH Locality 123 (MNA 939) on the Paunsaugunt Plateau represents a channel lag.

The two localities (UMNH localities 161, 162) on the Markagunt Plateau are from Cedar Canyon. Both are “blind wash” (Eaton 2004) mudstone localities that contain complete gastropods and ostracods and there is no evidence of extensive reworking. There are well over 100 m of the middle member in Cedar Canyon (see Eaton et al. 2001) and it is possible that subsidence began earlier to the west adjacent to the thrust belt than in the Kaiparowits–Paunsaugunt area. The mammals from these localities appear somewhat more primitive than those from the Dakota Formation of the Kaiparowits Plateau and could be a bit older, but certainly not older than early Cenomanian (Eaton 2010).

Straight Cliffs Formation, Smoky Hollow Member

Peterson (1969) named the Smoky Hollow Member and divided it into three parts: (1) a lower coal zone which has considerable brackish water influence; (2) a barren middle zone representing floodplain deposits; and (3) an upper conglomeratic bed that he referred to as the Calico bed. The fossils reported here come from the middle barren unit. There have as yet been no radiometric dates generated from the Smoky Hollow Member. Peterson (1969) dated the underlying Tibbet Canyon Member based on the late middle Turonian index fossil Inoceramus howelli White, 1876 which indicates the upper part of the late middle Turonian Prionocyclis hyatti zone of Obradovich and Cobban (1975). As there is no marked unconformity between the Tibbet Canyon and Smoky Hollow members it is likely that the Smoky Hollow is late Turonian in age.

The only significantly productive localities that contain anurans are from the barren middle zone of the Smoky Hollow Member on the Kaiparowits Plateau. UMNH Locality 129 (MNA 995) is in a mudstone and represents a floodplain accumulation. UMNH 1080 (MNA 1212) is in a friable sandstone found low in the middle member that may represent a crevasse splay deposit.

Straight Cliffs Formation, John Henry Member

Peterson (1969) reported Volviceramus involutus from low in the John Henry Member, a taxon considered to represent the middle Coniacian (e.g., Merewether et al. 2007, Fig. 5). Taxa from the middle and upper part of the member, including the ammonite Desmoscaphites, suggest that the upper part of the John Henry Member does not extend beyond the Santonian (Eaton 1991). As such, the member ranges from middle Coniacian to possibly late Santonian.

Most of the localities reported here from the John Henry Member represent floodplain or pond mudstones. Several of the most significant localities (e.g., UMNH localities 424, 427) are blind wash sites and contain delicate mammal jaws and complete ostracods. UMNH Locality 856 is present very low in the John Henry Member on the Paunsaugunt Plateau and is 21.5 m above the top of the Smoky Hollow Member and may be, due to its low stratigraphic position within the member, Coniacian in age. This locality is a very poorly sorted and may represent a proximal crevasse splay setting.

Wahweap Formation

This formation is over 400 m thick on the Kaiparowits Plateau. Radiometrically datable ashes are rare, although Jinnah et al. (2008) reported a 40Ar-39Ar date from about 60 m above the base of the formation of 80.1 ± 0.3 Ma. A radiometric date of 75.96 ± 0.14 Ma for the overlying lower unit of the Kaiparowits Formation and estimates of depositional rates suggest the upper age limit on the Wahweap Formation is 76.1 Ma (Roberts et al. 2005). This suggests the age of the Wahweap Formation is middle Campanian. Eaton and Cifelli (1988) originally correlated the mammalian fauna from the Wahweap Formation with the fauna from the Milk River Fauna in Alberta, Canada (Aquilan North American Land-Mammal “Age”); however, later studies (Eaton 2006a) of mammals from the upper part of the John Henry Member of the Straight Cliffs Formation (Santonian) revealed a stronger correlation of that fauna to the Milk River fauna than to the Wahweap fauna. A Santonian age for the upper member (which contains all the vertebrate fossils in the formation) of the Milk River Formation has been well documented on the basis of palynomorphs (Braman 2002) and U-Pb geochronology (Payenberg et al. 2002). As such, the Wahweap fauna is younger than the Santonian Aquilan Land-Mammal "Age" and older than the late Campanian Judithian Land-Mammal "Age."

UMNH Locality 82 is a lag deposit very low in the Wahweap Formation of the Kaiparowits Plateau, whereas UMNH Locality 130 is a floodplain mudstone in the upper member which contains abundant delicate gastropods. Localities on the Paunsaugunt Plateau represent a mixture of sandstone lags (UMNH localities 77, 80) or floodplain mudstones (UMNH localities 83 (MNA 1073), 118, 807, 1074). Locality 78 is in a floodplain mudstone that has been thrust into position, so its stratigraphic position can only be roughly estimated.

Two localities on the Markagunt Plateau (Cedar Canyon) may be from strata equivalent to the Wahweap Formation (see Eaton et al. 2001; Eaton 2006b), but here the term “Formation of Cedar Canyon” is used following the suggestion by Moore et al. (2004). Locality 10 is from just above a conglomeratic horizon considered by some to be the Drip Tank Member of the Straight Cliffs Formation (see discussion in Eaton et al. 2001, p.343; Moore et al. 2004) and therefore would be a locality equivalent to the basal Wahweap Formation. A locality more than 250 m higher, UMNH Locality 11, does appear to be Campanian in age (Eaton 2006b) and may also be from strata equivalent to the Wahweap Formation.

Kaiparowits Formation

The Kaiparowits Formation is about 855 m thick (Eaton 1991; 860 m in Roberts et al. 2005), consists of fluvial rocks and is only present on the Kaiparowits Plateau (although the base of the formation is present to the east in the “beds on Tarantula Mesa” in the Henry Basin; Eaton 1990). Radiometric dates (Roberts et al. 2005) and mammalian faunas (e.g., Eaton and Cifelli 1988; Eaton 2002) have suggested a late Campanian (but not latest) age for the Kaiparowits Formation. The youngest 40Ar-39Ar reported from the Kaiparowits Formation is 74.21 ± 0.18 Ma (Roberts et al. 2005) which places the Kaiparowits Formation in the early part of the late Campanian. Most of the anuran assemblages are from localities in the lower 400 m of the formation, with the exception of two localities higher up in the unit: locality TB8 (see Eaton 1991, Fig. 16) and UMNH Locality 1082; the latter was discovered in 2008 at 747 m above the base of the formation and, as yet, no mammals have been studied from the locality. Depositional rates and poor soil development suggest very rapid deposition and a rate as high as ~41 cm/ka has been suggested by Jinnah et al. (2008).

Most of the localities (localities 24, 25, 56, 57, 108) are in floodplain mudstones that preserve delicate material often accompanied by abundant and well-preserved fresh water invertebrates. Locality 1078 is a claystone that is packed with complete gastropods and bivalves. Although there is breakage in these localities, it is likely that there has been little transport of specimens. Localities 51 and 54 are sandy mudstones with abundant freshwater invertebrate shell fragments, suggesting a higher degree of transport than at the other localities.

Palaeoecology

The Upper Cretaceous rocks of southern Utah were deposited in relatively close proximity to or within the Western Interior Seaway (e.g., Roberts and Kirschbaum 1995). The upper part of the Dakota Formation, the Tropic Shale, and part of the Straight Cliffs Formation were deposited in the seaway. This seaway connected the Arctic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico and had a stabilizing effect on the climate of the Western Interior of North America. The climate throughout this interval appears to have been subtropical or, at least, very wet and warm temperate. This is established for the lowest unit in the sequence, the Dakota Formation, based on palynomorphs (May and Traverse 1973), to the top of the section, the Kaiparowits Formation, based on floras and paleosols (Roberts 2007). Angiosperms are diverse and the most common elements of the flora throughout the section. Coals are present in the Dakota Formation and in the Smoky Hollow and John Henry members of the Straight Cliffs Formation. Brackish water influence is also found throughout the section, except for the Kaiparowits Formation where there may be only rare brackish influence in the lower part (Roberts 2007). As such, the palaeoecology of the sequence from which the anurans were recovered was relatively consistent throughout the interval. Perhaps the greatest palaeoecologic variation is related to changes of elevation and groundwater tables west of the Kaiparowits Plateau region towards the Sevier thrust belt. This is reflected in relatively drab, organic-rich floodplain mudstones in the Kaiparowits region, as compared with the well-variegated equivalent floodplain deposits on the Paunsaugunt and Markagunt plateaus. This variation has not yet been assessed palaeoecologically, but there are certainly significant mammalian faunal differences when comparing the Paunsaugunt and Markagunt plateaus to the Kaiparowits Plateau (Eaton 1999, 2006b).

Materials and methods

All specimens were recovered by quarrying localities and then processing the rock by wet screen-washing. Most of the anuran bones (both tiny as well as larger ones) were broken but the broken surface can be both fresh as well as worn, presumably indicating various degrees of their secondary transport. In no way was the damage to the bones caused by the screen-washing process because broken bones were recovered even when very gentle agitation was applied.

Dermal bones of the skull, such as the frontoparietals, maxillae, parasphenoid and squamosals, are the most significant for anuran taxonomy. Unfortunately, some of these bones may be small and delicate; thus, they are rarely abundant in the fossil record. Among postcranial elements, the most frequently used are the humeri and ilia. However, because the lateral and medial cristae of the humeri serve as insertion areas of muscles used in amplexus, their degree of development may reflect sexual, not taxonomic, differences. The radioulnae and tibiofibulae may be quite common in the fossil record, yet those bones are morphologically uniform and, thus, provide little or no taxonomic information. Those bones can, however, provide information about the sizes of animals.

Several hundred isolated bones (see graph in Fig. 3) were investigated, but only some of them could be assigned to previously described taxa. Although many of the remaining specimens likely represent different taxa, we decided not to establish any new taxa on the basis of disarticulated elements because we realize that it is difficult to reliably associate elements from different parts of the skeleton. Some localities (e.g., Paul's locality, see Fig. 11, below) produced large samples in which different morphs of particular elements, especially ilia, could be identified. Using these structural morphs as a proxy for taxonomic richness, it is possible to estimate the taxonomic diversities of anuran assemblages at a local scale. Finally, because of the extent of the geological time-span represented by the localities, we were able to identify some trends in the morphological transformations of anuran bones. In cases where osteological features are known to be related to a particular function (e.g., structures on the ilia serving for the insertion of muscles important for locomotion may provide information about the mode of locomotion), it was possible to draw conclusions on the way of life of these early frogs.

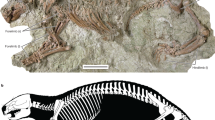

Anatomical terms used in text and investigated material. a Right premaxilla in outer (a-1), inner (a-2) and dorsal (a-3) views. The recess for the lower prenasal cartilage (cartilago praenasalis inferior) marked by arrow. b Right maxilla in dorsal (b-1), outer (b-2) and inner (b-3) views. c Sphenethmoid in dorsal (c-1), ventral (c-2) and anterior (c-3) views. d Urostyle in dorsal view. e Right humerus in ventral view. f Left angular in dorsal view. g Left ilium in lateral view. Location of the oblique groove across the dorsal margin of the bone in some taxa marked by arrow. h Right scapula in outer view. Graph depicts numbers of investigated bones

We followed the osteological nomenclature of Sanchiz (1998, pp.4–10). The most frequently used terms are illustrated in Fig. 3. Anglicized terms are used here and there throughout the text. Other terms are explained in the text.

Institutional abbreviations: MCZ – Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Harvard, Massachusetts, USA; MNA – Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff, Arizona, USA; UMNH – Utah Museum of Natural History, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA. Except where indicated otherwise, all locality numbers are UMNH localities and all specimen numbers denote UMNH specimens.

Description of the material

Middle? Cenomanian (Fig. 4)

Dakota Formation, Cedar Canyon, localities 161, 162

Material:

3 prearticulars (12927, Fig. 4p; 12933, Fig. 4q; 13170, Fig. 4o); 9 maxillae (12909, Fig. 4h-1,2; 12910, Fig. 4f-1,2; 12924, Fig. 4k-1,2; 12925, Fig. 4n-1,2; 12926, Fig. 4j-1,2; 18427, Fig. 4g-1,2; 18408, Fig. 4m-1,2; 18428, Fig. 4i-1,2; 18429, Fig. 4l-1,2); 5 humeri (12894, Fig. 4a; 12929, Fig. 4d; 12934, Fig. 4e; 12938, Fig. 4c; 13006, Fig. 4b), 2 ilia (12936, Fig. 4r-1,2; 12983, Fig. 4s), 1 presacral vertebra (18420, Fig. 4w); 1 sacral vertebra (18418, Fig. 4x-1–3); 3 urostyles (12932, Fig. 4t; 12944, Fig. 4u; 12954, Fig. 4v-1–4).

Description:

Three types of prearticulars occur in the Dakota Formation of Cedar Canyon. UMNH 13170 (Fig. 4o) is characterized by a short but prominent coronoid process directed dorsomedially. From the level of this process posteriorly, Meckel's groove is not roofed and is represented only by a horizontal ledge. UMNH 12927 (Fig. 4p) differs from UMNH 13170 in having Meckel's groove well delimited dorsally by a sharp crista paracoronoidea which clearly separates it from the similarly well delimited depression on the dorsal surface of the coronoid process; the process is only moderately prominent medially. Also, UMNH 12933 (Fig. 4q) has its Meckel's groove well delimited by the crista paracoronoidea, but the dorsal surface of the coronoid process is convex.

Basically, two types of maxillae occur in the sample. Sculptured maxillae are mostly larger, whereas smooth maxillae are smaller. The larger maxillae are represented by UMNH 12910 (Fig. 4f-1,2) which is a fragment from the anterior portion of the right maxilla. Its inner surface slants down from the upper margin of the bone towards the margin of the lamina horizontalis. Posteriorly (to the right in Fig. 4f-1), the margin of the horizontal lamina becomes thinner and more extended medially, whereas it is thick and widely rounded in its anterior part. The outer surface of the bone is sculptured, except for a strip along the lower margin of the bone. The sculpture consists mostly of pits of various size and depth which, towards the lower part of the bone, tend to be larger; the rounded ridges separating them sometimes protrude as tubercles. UMNH 18427 (Fig. 4g-1,2) is another large, sculptured maxilla, represented by a fragment of the middle part of the bone. In contrast to UMNH 12910, its outer surface is covered by pitted sculpture. On the inner side of the bone, the tip of the pterygoid process is broken off. A comparatively deep sulcus for the palatoquadrate bar is delimited ventrally by a rounded horizontal lamina and dorsally by a ridge running parallel to the orbital margin. The latter is broad and slightly declined medially. UMNH 18429 (Fig. 4l-1,2) represents a comparatively large maxilla which bears reticular sculpture on its outer surface. It includes the pterygoid process (marked by arrow in Fig. 4l-1) but differs from other maxillae by its horizontal lamina which is, at least in its posterior section, represented by a thin ledge.

Cedar Canyon, middle?Cenomanian. a Right humerus (12894) in ventral view. b Right humerus (13006) in ventral view. c Right humerus (12938) in ventral view. d Left humerus (12929) in ventral view. e Left humerus (12934) in ventral view. f Right maxilla (12910) in inner (f-1) and outer (f-2) views. g Left maxilla (18427) in inner (g-1) and outer (g-2) views. h Right maxilla (12909) in inner (h-1) and outer (h-2) views. i Right maxilla (18428) in inner (i-1) and outer (i-2) views. j Left maxilla (12926) in inner (j-1) and outer (j-2) views. k Left maxilla (12924) in inner (k-1) and outer (k-2) views. l Maxilla (18429) in inner (l-1) and outer (l-2) views. Arrow marks the pterygoid process. m Maxilla (18408) in inner (m-1) and outer (m-2) views. Arrow marks the level where palatine process was broken off. n Right maxilla (12925) in inner (n-1) and outer (n-2) views. o Left praearticulare (13170) in dorsal view. p Left praearticulare (12927) in dorsal view. q Right praearticular (12933) in dorsal view. r Left ilium (12936) in outer (r-1) and inner (r-2) views. s Left ilium (12983) in outer view. t Urostyle (12932) in dorsal view. u Urostyle (12944) in dorsal view. v Urostyle (12954) in dorsal (v-1), right lateral (v-2), anterior (v-3) and left lateral (v-4) views. w Presacral vertebra (18420) in ventral view. x Sacral vertebra (18418); centrum in dorsal (x-1), posterior (x-2) and ventral (x-3) views. All are at the same scale

Other maxillae are represented by small, unsculpted morphs. UMNH 12909 (Fig. 4h-1,2) is a posterior part of the right maxilla with posterior teeth. The horizontal lamina terminates abruptly (with no trace of the pterygoid process), its posteriorly facing edge is slightly concave and nearly perpendicular to the inner surface of the bone. The dorsal surface of the horizontal lamina is the bottom of the groove for the palatoquadrate bar, the roof of which is produced by the vertical part of the bone somewhat declined medially. The outer surface of the bone is smooth. UMNH 12926 (Fig. 4j-1,2) appears to be the anterior part of the left maxilla the dorsal edge of which is intact. Its horizontal lamina is thick and broadly rounded, the outer surface is smooth. UMNH 12924 (Fig. 4k-1,2) has its dorsal part entirely broken off but apparently it is the posterior part of the left maxilla at the level of the posterior end of the horizontal lamina. The latter tapers posteriorly and has no pterygoid process. The outer surface of the bone is smooth.

There are also several maxillae in the sample, which represent transitions between the two morphotypes described above. UMNH 18408 (Fig. 4m-1,2), although also sculptured on its outer surface, represents a small frog. Its outer surface is covered by irregular pitted sculpture; the pits sometimes tend to fuse into grooves, and their ridges may produce moderately prominent pustules here and there. The arrow in Fig. 4m-2 marks the margin where the palatine process is broken off. On the inner surface of the bone, there is a shallow depression which may be interpreted as the fossa maxillaris. The remaining part of the inner side is a smooth surface extending onto the lamina horizontalis which, as a result, is not well delimited dorsally. UMNH 18428 (Fig. 4i-1,2) is the posterior part of a large right maxilla which is rather worn, so it cannot be determined whether it had a posterior outgrowth for articulation with the quadratojugal. Its outer surface is covered only by a faint irregular rugosity, so it cannot be included among sculptured taxa. On the inner surface, the horizontal lamina is comparatively thin and not terminated by the pterygoid process. Instead, the lamina terminates rather abruptly on the inner surface of the bone. Between the orbital margin and horizontal lamina is a broad horizontal depression that extends onto the inner surface of the posterior part of the bone. Also, UMNH 12925 (Fig. 4n-1,2), which is the anterior part of the right maxilla, represents a larger species. It is characterized by a thick and rounded horizontal lamina, and by a smooth outer surface.

All humeri are, disregarding size, rather uniform in their asymmetrical structure: the lateral epicondyle is absent or, as in the specimens where the distal part of the bone is damaged (UMNH 12894, Fig. 4a; UMNH 13006, Fig. 4b), it was developed to a much lesser degree. Two larger humeri have their lateral and medial cristae either absent (UMNH 12894, Fig. 4a) or weakly developed (UMNH 12934, Fig. 4e). In those specimens where the caput is preserved, the fossa cubitalis is deep but narrow. Only in UMNH 12894 does it seem to be triangular in shape. UMNH 13006 (Fig. 4b) and 12938 (Fig. 4c) are small (estimated length about 3 mm), their medial crista is indistinct but the lateral crista, although short, is thickened along its margin (see arrows in Fig. 4b and c). UMNH 12929 (Fig. 4d), which is intermediate in size between the smaller UMNH 13006 and 12938 and 12894 and the larger UMNH 12934, has its lateral crista well preserved, terminating on the lateral surface of the articular head. Both of its cristae are thickened along their margins, and a deep rounded ridge continues onto the ventral surface of the medial epicondyle. UMNH 12934 (Fig. 4e) has its medial epicondyle confluent with the articular head.

Only two anuran ilia were recovered from the Dakota Formation of Cedar Canyon. UMNH 12936 (Fig. 4r-1,2) is small (estimated length about 3 mm) and its characteristic features are absence of the dorsal tubercle (“tuber superius” in Fig. 3g), the acetabulum apparently not extending beyond the anteroventral outline of the bone, and a depression on the dorsal margin of the bone which continues as a distinct oblique groove onto its inner surface. The groove is delimited ventrally by a rounded ledge coming from the pars ascendens (Fig. 4r-2). UMNH 12983 (Fig. 4s) is characterized by an extensive acetabulum slightly extending anteroventrally beyond the outline of the bone.

All presacral vertebrae in the sample are fragmentary. UMNH 18420 (Fig. 4w) has the neural arches including zygapophyses broken off so it cannot be determined whether it was procoelous or opisthocoelous. The only feature which can be observed is a faint median keel on the ventral surface of the centrum.

The sacral vertebra UMNH 18418 (Fig. 4x-1–3) belongs to a larger frog which was procoelous, and its sacrourostylar articulation was bicondylar.

The urostyle UMNH 12932 (Fig. 4t) represents a small frog with bicondylar sacrourostylar articulation. In contrast, the more complete UMNH 12944 (Fig. 4u) has its articular cotyle in the shape of a horizontal ellipsoid, suggesting that the articulation was monocondylar. Also a pair of stout transverse processes were developed. UMNH 12954 (Fig. 4v-1–4) was also monocondylar, but its articulation cotyle was circular and apparently there were no diapophyses.

Late Cenomanian (Fig. 5)

Dakota Formation, Alton, Locality 123; Bulldog Bench, localities 804, 27

Material:

2 maxillae (13076, Fig. 5h; 13102); 4 prearticulars (13124, Fig. 5b; 13155, Fig. 5a; 13182, 13183); 1 scapula (13161, Fig. 5i); 8 humeri (13074, Fig. 5c; 13077, Fig. 5e; 13121, Fig. 5g; 13123; 13128; 13140; 13160, Fig. 5d; 13163, Fig. 5f); 1 radioulna (13122); 4 ilia (13071, Fig. 5m; 13156, Fig. 5j; 13158, Fig. 5k; 13159, Fig. 5l); 1 pair of ischia (13162); 2 femora (13139, 13141); 15 tibiofibulae (13125–13127, 13129–13138, 13142, 13151).

Description:

Both maxillae are represented by only small fragments that have a thick and rounded horizontal lamina in the anterior portion of the bone (UMNH 13076, Fig. 5h) and a smooth outer surface.

The prearticular UMNH 13124 (Fig. 5b) is characterized by having its coronoid process widely convex medially, only moderately thickened along its margin, and that the dorsal crista delimiting Meckel's groove passes into the crista paracoronoidea by a sudden turn (see arrow in Fig. 5b). The dorsal surface of the coronoid process is smooth and flat. UMNH 13155 (Fig. 5a) is larger and its crista paracoronoidea disappears on the posterior part of the bone. The medial margin of the coronoid process is slightly elevated so the dorsal surface of the process is depressed. The depression and elevated margin extend nearly to the posterior end of the bone.

Bulldog Bench, late Cenomanian. a Right praearticulare (13155) in dorsal view. b Left prearticular (13124) in dorsal view. Break of the dorsal margin of the sulcus Meckeli and crista paracoronoidea marked by arrow. c Right humerus (13074) in ventral view. d Left humerus (13160) in ventral view. e Left humerus (13077) in ventral view. f Left humerus (13163) in ventral view. g Right humerus (13121) in ventral view. h Right maxilla (13076) in lingual aspect. i Right scapula (13161) in dorsal view (posterior margin below). j Left ilium (13156) in lateral view. Oblique groove filled with sediment marked by arrow. k Left ilium (13158) in lateral view. Oblique groove filled with sediment marked by arrow. l Right ilium (13159) in lateral view. m Left ilium (13071) in lateral view. All are at the same scale

Only the posterior part of the right scapula UMNH 13161 (Fig. 5i) is preserved. The glenoid is large and prominent, but details of the sinus interglenoidalis and pars acromialis cannot be seen.

All the humeri are uniform in their total absence of the lateral epicondyle, and in having a deep fossa cubitalis that is restricted only to the narrow area adjacent to the caput. A distinct rounded ridge originates on the ventral surface of the humeral shaft and continues onto the medial epicondyle. Both the medial and lateral cristae are slightly thickened along their margins and neither expand beyond the outlines of the bone (UMNH 13160, Fig. 5d), or the medial crista is only slightly expanded and declined dorsally (UMNH 13077, Fig. 5e; 13163, Fig. 5f). Only in UMNH 13121 (Fig. 5g) is the margin of the medial crista convex. As evidenced by preserved humeral shafts UMNH 13121 (Fig. 5g), 13123, 13128, and 13140, the crista ventralis is simple and undivided. UMNH 13074 (Fig. 5c) is about twice as big as other humeri but is also asymmetrical, with the lateral epicondyle absent.

The ilia UMNH 13156 (Fig. 5j) and 13158 (Fig. 5k) are small (estimated total lengths less than 5 mm). Their characteristic features are large acetabula with the anteroventral margin exceeding the outlines of the bone, and an indistinct shallow groove running from the lateral base of the dorsal tubercle anteroventrally along the outer surface of the iliac shaft (see arrows in Fig. 5j and k). On the inner surface of the bone, there is a crista running from the pars ascendens to the lower part of the inner surface of the shaft where it disappears; the crista is somewhat sharper in UMNH 13158 than in UMNH 13156. The main difference between both ilia is that in UMNH 13156 (Fig. 5j) the dorsal tubercle is extensive but laterally compressed, thus resembling a convex crest with a sharp and irregular edge. Laterally, the dorsal tubercle is delimited by a wide groove separating it from the acetabulum; this is why the upper margin of the dorsal tubercle is slightly declined laterally. In UMNH 13158 (Fig. 5k), the dorsal tubercle has a long elevated base but only its middle part is prominent. It is also only minimally compressed laterally, meaning its dorsal margin is rounded and does not form a sharp edge.

UMNH 13159 (Fig. 5l) is similar to UMNH 13156 and 13158 in size, but is different in having a smaller acetabulum (although its anteroventral margin far exceeds the outline of the bone) and in the asymmetrical shape of the dorsal tubercle, which is developed as a prominent knob declined anterolaterally. The anterior margin of the tubercle is located at the level of the anterior margin of the acetabulum.

The ilium UMNH 13071 (Fig. 5m) is markedly different, because it is about twice as large as the three previously described specimens and its acetabulum is a mere depression in the bone, except for a short anterior section that is elevated. The dorsal tubercle is absent. A distinctive feature is a short, rounded ridge running from the tip of the pars ascendens parallel to the upper margin of the acetabulum and terminating at the level of its anterior elevated rim.

The tibiofibulae bear no diagnostic features. UMNH 13127 and 13135 are small (estimated lengths 9–10 mm), with large foramen for the arteria tibialis antica; before entering the foramen, the artery was located in a well defined groove.

Turonian (Fig. 6)

Straight Cliffs Formation, Smoky Hollow Member, Jimmy Canyon, Locality 129; Slickrock Bench, Locality 1080

Material:

1 premaxilla (13463, Fig. 6s-1,2); 2 maxillae (13455, Fig. 6r-1,2; 18371, Fig. 6q); 1 ?frontoparietal (18370, Fig. 6o); 2 scapulae (13464, Fig. 6cc-1,2; 13465, Fig. 6bb-1,2); 18 humeri (13435, Fig. 6n; 13451, Fig. 6k; 13456; 18350, Fig. 6a; 18351, Fig. 6c; 18352, Fig. 6b; 18353, Fig. 6e; 18354, Fig. 6f; 18356, Fig. 6d; 18357, Fig. 6g; 18358; 18359, Fig. 6h; 18360, Fig. 6m; 18361, Fig. 6l; 18362, Fig. 6j; 18363; 18364, Fig. 6i; 18365); 4 radioulnae (13432; 13433; 13439; 13452); 9 ilia (13457, Fig. 6aa; 13458, Fig. 6w-1,2; 13459, Fig. 6z; 13460, Fig. 6y; 13461, Fig. 6x-1,2; 13462; 18355, Fig. 6t; 18366, Fig. 6u; 18367, Fig. 6v-1,2); 1 pair of ischia (18372); 1 urostyle (18368, Fig. 6p); 1 radioulna (18369); 15 tibiofibulae (13434; 13437; 13438; 13443; 13453; 18240; 18375–18383).

Description:

Only the lower part of the premaxilla UMNH 13463 (Fig. 6s-1,2) is preserved but it is clear that its horizontal lamina was thin and extensive, and the recess for the inferior prenasal cartilage (marked by arrows in Fig. 3a-2 and 6s-1) is subdivided by a vertical ridge. The outer surface of the bone is smooth. The estimated number of tooth positions is nine or ten.

The maxilla UMNH 13455 (Fig. 6r-1,2) is an anterior part of the bone, with a deep fossa on its inner side and a smooth outer surface. UMNH 18371 (Fig. 6q) is also a small fragment of the maxilla with a thin and dorsally rather concave horizontal lamina. Similar to UMNH 13455, it is smooth on its outer surface.

Jimmy Canyon, Turonian. a Right humerus (18350). b Right humerus (18352). c Left humerus (18351). d Left humerus (18356). e Right humerus (18353). f Right humerus (18354). g Left humerus (18357). h Right humerus (18359). i Right humerus (18364). j Left humerus (18362). k Left humerus (13451). l Left humerus (18361). m Left humerus (18360). n Left humerus (13435). o Fragment of dermal bone (maxilla?) (18370). p Urostyle (18368) in adorsal view. q Maxilla (18371) in medial view. r Maxilla (13455) in medial (r-1) and lateral (r-2) views. s Premaxilla (13463) in medial (s-1) and lateral (s-2) views. The partition in the recess for the inferior prenasal cartilage is marked by arrow. t Right ilium (18355) in lateral view. u Left ilium (18366) in lateral view. v Left ilium (18367) in lateral (v-1) and medial (v-2) views. w Right ilium (13458) in lateral (w-1) and medial (w-2) views. x Right ilium (13461) in medial (x-1) and lateral (x-2) views. y Right ilium (13460) in lateral view. z Left ilium (13459) in lateral view. aa Left ilium (13457) in lateral view. bb Right scapula (13465) in outer (bb-1) and inner (bb-2) views. cc Left scapula (13464) in outer (cc-1) and inner (cc-2) views. All are at the same scale. Humeri are in ventral view

A small fragment of a dermal bone (UMNH 18370, Fig. 6o), covered by a pit-and-ridge scupture, could be a part of an anuran frontoparietal.

Two scapulae occur in the sample. In both, the processus glenoidalis is much more robust than the pars acromialis; however, UMNH 13464 (Fig. 6cc-1,2) is larger and its glenoid is semilunar and occupies only half of the glenoid process. On its inner surface is a rounded ridge (see arrow in Fig. 6cc-2) coming from the glenoid process; however, it does not continue onto the pars suprascapularis. UMNH 13465 (Fig. 6bb-1,2) also has its glenoid subdivided, although to a lesser degree than in UMNH 13464. The general morphology of these two scapulae may suggest that they belong to a single taxon or to closely related taxa.

Several types of humeri can be recognized in the Turonian samples. The smallest one is UMNH 13435 (Fig. 6n). Only the proximal part of its caput is preserved, but it is obvious that it was ossified (thus not representing an immature, juvenile individual), with no fossa cubitalis. Its medial and lateral cristae were poorly (if at all) developed. The ventral surface of the distal portion of the shaft is regularly rounded, and only a moderately elevated ridge joins the medial surface of the caput (thus not continuing onto the medial epicondyle, if the latter was present). UMNH 13456 is similar in size, but its caput is completely broken off. Both its medial and lateral cristae are moderately developed, and the fossa cubitalis is triangular.

The majority of the humeri are somewhat larger than the two described above and they are clearly asymmetrical, with a large medial epicondyle separated from the caput by a deep incision. In most specimens, there is a rounded ridge coming from the shaft onto the ventral surface of the medial epicondyle. The lateral crista does not terminate on the lateral epicondyle. Instead, it joins the lateral surface of the caput. The fossa cubitalis may be a narrow groove along the proximal surface of the caput (UMNH 13451, Fig. 6k) or an extensive depression (UMNH 18360, Fig. 6m) from which the caput is very prominent (observable in Fig. 6m in which the humerus is in lateroventral view to show the extensive fossa cubitalis).

Some of the UMNH humeri (18350, Fig. 6a; 18353, Fig. 6e; 18354, Fig. 6f; 18358; 18362, Fig. 6j; 18365; possibly also 18357, Fig. 6g) each have the lateral epicondyle small, their cristae convex and swollen along their margins, and the fossa cubitalis shallow or absent because the rounded ridge coming from the crista ventralis turns towards the medial epicondyle, rather than being bifurcated. UMNH 18360 (Fig. 6m) and 18361 (Fig. 6l) are similar, but the lateral epicondyle is completely absent and the lateral crista is bent ventrally so that an extensive depression arises proximolateral to the caput humeri (see arrow in Fig. 6m). UMNH 13451 (Fig. 6k), 18351 (Fig. 6c), 18352 (Fig. 6b), 18356 (Fig. 6d) and 18364 (Fig. 6i) also belong to this group. UMNH 18359 (Fig. 6h) seems to be a juvenile, but also belongs to this group.

The UMNH ilia 13458 and 13460 (Fig. 6w-1,2 and y, respectively) are each characterized by a large acetabulum with well-defined and elevated margins. The acetabulum almost completely occupies the dorsoventral diameter of the acetabular region of the ilium; its anteroventral portion slightly exceeds the outlines of the bone. The dorsal tubercle is prominent, compressed to form a comparatively thin lamina, moderately declined laterally and, if seen in lateral view, it is squarish and slightly declined anteriorly. UMNH 13459 (Fig. 6z) and possibly also UMNH 18355 (Fig. 6t) are similar in general morphology and in having a large acetabulum; the only difference is in shape of the dorsal tubercle which, although laterally compressed like in UMNH 13458 and 13460 (not as much in UMNH 18355), tapers towards its top and is rounded. It is also not declined laterally.

The second category of ilia is characterized by a complete absence of the dorsal tubercle. UMNH 13457 (Fig. 6aa) differs from all others in that the dorsal margin between the iliac shaft and the pars ascendens is straight. Its acetabulum is comparatively large. Two other ilia with no dorsal tubercle, UMNH 18366 and 18367 (Fig. 6u and v-1,2, respectively), are characterized by having their shaft separated from the posterior part of the bone by a shallow depression on the dorsal surface of the bone, which makes the shaft distinctly arch-like.

The ilium UMNH 13461 (Fig. 6x-1,2) is intermediate between the ilia with a prominent dorsal tubercle and those without a dorsal tubercle. In lateral view, its tubercle is only moderately prominent. There is an oblique groove running across the dorsal margin of the bone anteromedially just in front of the dorsal tubercle. A characteristic feature on the inner surface of the bone is a straight crista between the pars ascendens and lower margin of the iliac shaft (observable in Fig. 6x-1).

The urostyle UMNH 18368 (Fig. 6p) seems to be monocondylar. Its condyloid fossa is a horizontal ellipsoid filled with sediment; if there was a vertical partition, it is broken off or obscured by matrix. Both transverse processes are robust, but dorsoventrally compressed and continue posteriorly as a horizontal ledge.

Coniacian (Fig. 7)

Straight Cliffs Formation, John Henry Member, Heward Creek, Locality 856

Material:

2 scapulae (19370, Fig. 7c-1,2; 18978, Fig. 7d-1,2); 3 ilia (19366, Fig. 7b; 19368; 19371; Fig. 7a-1,2); 1 femur (19365); 4 tibiofibulae (19363; 19364; 19367; 19369)

Description:

UMNH 19370 (Fig. 7c-1,2) is a scapula that is missing on both its medial and lateral ends. In spite of this damage, it seems that its glenoid was declined lateroventrally, rather than laterodorsally. Its interglenoidal sinus is clearly seen in ventral aspect, but dorsally it is obscured by a thin lamina. On the outer surface of the bone, an oblique ridge runs from the posterior part of the sinus towards the posterior margin of the bone. UMNH 18978 (Fig. 7d-1,2) is larger, but also seems to have the interglenoidal sinus developed only on the outer side of the bone, whereas it is obscured on the inner side.

The ilium UMNH 19366 (Fig. 7b) has its shaft broken off, but its acetabular region is well preserved. The dorsal part of the acetabulum is a deep depression in the bone, whereas its anterior and anteroventral margins protrude as a vertical ridge. Consequently, the iliac portion of the acetabulum is strongly declined posteriorly. The dorsal margin of the pars ascendens is nearly a straight continuation of the dorsal margin of the iliac shaft. Anterior to the acetabulum is a distinct elevation, which is especially well delimited posteroventrally (see arrow in Fig. 7b). Anteriorly, the elevation continues onto the ventral surface of the iliac shaft. UMNH 19371 (Fig. 7a-1,2) is represented only by a shaft and anterior part of the acetabular portion of the bone. The acetabulum is declined posteriorly in the same way as in UMNH 19366. It also has an elevation on the lateral surface of the shaft which is more extensive (reaching the dorsal margin of the shaft), and is similarly well delimited posteroventrally by a distinct oblique border (marked by arrow in Fig. 7a-1). On its inner surface, it is characterized by a well-developed oblique ledge delimiting a groove running anteroventrally towards the lower margin of the shaft.

Early Santonian (Fig. 8)

Straight Cliffs Formation, John Henry Member, Sheep Creek, Locality 426; Casey’s Concretionary Horizon, locality 799

Material:

4 maxillae (18546; 18547, Fig. 8m-1,2; 18549; 18550); 1 prearticular (18560, Fig. 8l); 5 humeri (18508, Fig. 8a; 18557, Fig. 8d; 18564; 18566, Fig. 8c; 18567, Fig. 8b); 1 radioulna (18543); 10 ilia (18293, Fig. 8f-1,2; 18294; 18299, Fig. 8h-1,2; 18509, Fig. 8i; 18544, Fig. 8e; 18556, Fig. 8g; 19270, Fig. 8j; 19271; 19272; 19273, Fig. 8k); 1 femur (18563); 9 tibiofibulae (18295; 18297; 18298; 18300; 18301; 18302; 18548; 18561; 18562); 1 dermal bone (18510).

Description:

The maxillae are fragmentary, but appear uniform. UMNH 18547 (Fig. 8m-1,2) represents the anterior portion of the right maxilla with its horizontal lamina tapering anteriorly. Its dorsal margin is broken off. Sculpture on the outer surface consists of faint horizontal rounded ridges and grooves, which are absent only along the lower margin of the bone. UMNH 18546 and 18550 are small fragments, with smooth outer surfaces.

The prearticular UMNH 18560 (Fig. 8l) is large, with its coronoid process extensive and directed medially. It is moderately depressed on its dorsal surface. It appears that the groove for Meckel’s cartilage widens posteriorly, so it presumably extended over the whole width of the bone.

Sheep Creek, Casey’s Concretionary Horizon, early Santonian. a Right humerus (18508) in ventral view. b Right humerus (18567) in ventral view. c Left humerus (18566) in ventral view. d Left humerus (18557) in ventral view. e Left ilium (18544) in lateral view. f Right ilium (18293) in medial (f-1) and lateral (f-2) views. g Left ilium (18556) in lateral view. h Left ilium (18299) in lateral (h-1) and medial (h-2) views. i Right ilium (18509) in lateral view. j Right ilium (19270) in lateral view. k Right ilium (19273) in lateral view. l Left praearticular (18560) in dorsal view. m Right maxilla (18547) in outer (m-1) and inner (m-2) views. All are at the same scale

The humeri are rather uniform and are best exemplified by UMNH 18508 (Fig. 8a). Its medial epicondyle is large and well separated from the caput, whereas the lateral epicondyle is absent so the lateral crista is confluent with the lateral surface of the caput. Neither the lateral nor the medial cristae are prominent relative to the corresponding margins of the humeral shaft and are only slightly swollen along their margins. The fossa cubitalis is deep, narrow, and declined ventrolaterally, due to a prominent rounded ridge continuing from the crista ventralis of the shaft to the medial epicondyle. UMNH 18567 (Fig. 8b) is similar (although its medial epicondyle is broken away) and the only difference is that the medial crista is not developed. UMNH 18566 (Fig. 8c) is also generally similar, but differs in that the keel on the medial epicondyle is not confluent with the medial ridge on the shaft and that the fossa cubitalis is shallow. Both the medial and lateral cristae are poorly developed. UMNH 18564 is similar, although much damaged.

The humerus UMNH 18557 (Fig. 8d) differs by virtue of its small size and that its lateral epicondyle appears to be better developed. The medial crista is absent and only the lateral one is developed.

Only ilia without a dorsal tubercle were recovered from the early Santonian strata. UMNH 18293 (Fig. 8f-1,2) has a comparatively large acetabulum which does not extend beyond the level of the anteroventral margin of the bone. The dorsal acetabular margin is moderately elevated and rounded, whereas the anteroventral margin is a prominent perpendicular edge. The dorsal margin of the bone is nearly straight. On the inner surface of the bone, there is a distinct but shallow oblique groove that runs anteroventrally towards the lower margin of the shaft; even though it is much more fragmentary, UMNH 19271 has a similar oblique groove. UMNH 18556 is similar if observed in lateral aspect (Fig. 8g); however, its medial surface is smooth, without an oblique groove. UMNH 18509 (Fig. 8i), 19270 (Fig. 8j) and 19273 (Fig. 8k) are basically the same as UMNH 18556; the only slight differences are that the dorsal margin is moderately depressed in the transition between the acetabular portion of the bone and the iliac shaft and that the acetabulum is larger, with its margin reaching the level of the anteroventral margin of the bone. The oblique groove on the inner surface is indistinct or very faint. The seemingly developed dorsal tubercle (Fig. 8i and j) is an artefact caused by the posterior part of the dorsal margin of the bone having been broken away.

UMNH 18299 (Fig. 8h-1,2) is a fragment that represents the proximal portion of the iliac shaft. It has an oblique groove that traverses the dorsal margin of the bone, however, it does not continue onto the medial surface of the bone.

Middle Santonian (Fig. 9)

Straight Cliffs Formation, Old Merrill Ranch, locality 419; Henderson Canyon, locality 99; Casey’s Shell Hash Locality, locality 781; Willis Creek, locality 821; Divide between Noon and Mud Creeks, locality 843

Material:

1 frontoparietal (19288, Fig. 9e-1,2); 7 maxillae (18513, Fig. 9b-1,2; 18525, Fig. 9c-1,2; 19279, Fig. 9f-1,2; 19287, Fig. 9a-1,2; 19299; 19360, Fig. 9d-1,2; 19362); 4 prearticulars (18217, Fig. 9g; 18239; 18529; 19278, Fig. 9h); 1 atlas (18516, Fig. 9y-1–3); 1 urostyle (19289, Fig. 9ee-1,2); 1 scapula (18511); 8 humeri (18204; 18214, Fig. 9dd; 18216, Fig. 9aa-1,2; 18223, Fig. 9cc; 18225; 18234; 18512, Fig. 9z; 18541, Fig. 9bb); 7 radioulnae (18209, 18236, 18523, 18526, 18530, 18533, 19307); 26 ilia (18199; 18211, Fig. 9o; 18212, Fig. 9v; 18213, Fig. 9x; 18218, Fig. 9p; 18220, Fig. 9u; 18221, Fig. 9-n; 18222, 18224; 18226; 18227, Fig. 9k; 18228, Fig. 9s; 18229, Fig. 9i; 18230; 18231, Fig. 9j; 18232; 18233, Fig. 9t; 18235; 18237; 18539, Fig. 9w; 19293, Fig. 9l; 19303, Fig. 9q; 19305; 19355, Fig. 9m; 19356, Fig. 9r; 19358); 4 femora (18200, 18205, 19291; 19302); 31 tibiofibulae (18193–18198, 18201, 18203, 18238, 18514, 18515, 18518–18520, 18527, 18528, 19277; 19281–19285, 19292, 19294–19298, 19300, 19301; 19359).

Description:

The frontoparietal UMNH 19288 (Fig. 9e-1,2) was paired, with a smooth dorsal surface and straight orbital margin. It is slightly broader across its parietal portion than across its frontal portion. In ventral aspect, a low, rounded crista runs along the lateral margin of the bone. The frontoparietal incrassation (see Fig. 9e-1), which is a thickened part of the frontoparietal that in the articulated skull fits into the large foramina in the roof of the braincase (Jarošová and Roček 1982), is separated from the rounded crista by an irregular groove running parallel to the margin of the bone.

Most of the maxillae have smooth outer surfaces. UMNH 18513 (Fig. 9b-1,2) was slender and long. Its posterior part was of the same depth as its orbital section and the zygomaticomaxillar process only moderately protrudes from the dorsal margin of the bone. The horizontal lamina tapers towards its posterior end, but does not terminate in a distinct pterygoid process; instead, it terminates as a thin and posteriorly convex edge that is attached to the vertical part of the bone. The tooth row extends by two or three tooth positions beyond the level of the posterior end of the lamina horizontalis. UMNH 18525 and 19360 (Fig. 9c-1,2 and d-1,2) are each similar to UMNH 18513, but their zygomaticomaxillar process is even less prominent and their orbital margin is markedly declined medially.

Old Merrill Ranch, Henderson Canyon, Casey’s Shell Hash Loc., Divide between Noon and Mud Creeks, middle Santonian. a Right maxilla (19287) in labial (a-1) and lingual (a-2) views. b Right maxilla (18513) in labial (b-1) and lingual (b-2) views. c Right maxilla (18525) in labial (c-1) and lingual (c-2) views. d Left maxilla (19360) in labial (d-1) and lingual (d-2) views. e Right frontoparietal (19288) in ventral (e-1) and dorsal (e-2) views. f Left maxilla (19279) in labial (f-1) and lingual (f-2) views. g Right praearticulare (18217) in dorsal view. h Right praearticulare (19278) in dorsal view. i Left ilium (18229) in lateral view. j Left ilium (18231) in lateral view. k Left ilium (18227) in lateral view. l Left ilium (19293) in lateral view. m Left ilium (19355) in lateral view. n Left ilium (18221) in lateral view. o Right ilium (18211) in lateral view. p Right ilium (18218) in lateral view. q Right ilium (19303) in lateral view. r Right ilium (19356) in lateral view. s Right ilium (18228) in lateral view. t Left ilium (18233) in lateral view. u Left ilium (18220) in lateral view. v Left ilium (18212) in lateral view. w Right ilium (18539) in lateral view. x Left ilium (18213) in lateral view. y Atlas (18516) in dorsal (y-1), ventral (y-2) and posterior (y-3) views. z Right humerus (18512) in ventral view. aa Left humerus (18216) in ventral (aa-1) and dorsal (aa-2) views. bb Left humerus (18541) in ventral view. cc Left humerus (18223) in ventral view. dd Right humerus (18214) in ventral view. ee Urostyle (19289) in dorsal (ee-1) and ventral (ee-2) views. All are at the same scale

Other maxillae are sculptured. UMNH 19287 (Fig. 9a-1,2) is the middle part of a left maxilla. Its horizontal lamina is robust, with a widely rounded margin; however, towards the posterior (left in Fig. 9a-2), it is gradually extended by a thin, dorsomedially declined lamina that is terminated by the pterygoid process. The outer surface of the bone, except for its lower margin, is covered by faint pit-and-ridge sculpture. UMNH 19279 (Fig. 9f-1,2) is similar, but it is larger and the lower part of its sculptured area is covered by horizontal ridges, rather than by pits and ridges.

The two prearticulars in the sample differ markedly from one another. UMNH 18217 (Fig. 9g) preserves the complete coronoid process, which has a convex and slightly elevated margin; this is why there is an extensive depression between the coronoid process and crista paracoronoidea. In contrast, UMNH 19278 (Fig. 9h) has a narrow coronoid process, with a straight and markedly swollen margin. The rounded dorsal surface of the bone anterior to the coronoid process becomes flattened posteriorly and declined medioventrally into a groove running parallel with the margin of the process. Meckel’s groove is deep and delimited dorsally and ventrally by sharp cristae; it is located on the lateral surface of the bone at the level of the posterior part of the coronoid process.

The atlas UMNH 18516 (Fig. 9y-1–3) has both anterior cotyles widely separated, with a small pit in the midline. There is a posterior cotyle which, together with the anterior pit, suggests amphicoelous centrum. The centrum, however, is not pierced by the notochordal canal. The neural arches are broken off.

The urostyle UMNH 19289 (Fig. 9ee-1,2) is broken both posteriorly and anteriorly, so it is difficult to determine whether its articulation with the sacral vertebra was monocondylar or bicondylar. However, because the notochordal canal enters the body of the urostyle, we infer that the articulation likely was monocondylar. On both sides is a narrow, horizontal ledge extending anteriorly as a small, dorsoventrally compressed lateral process roofing a small intervertebral foramen. The dorsal margin of the bone is rounded with no keel.

UMNH 18511 is a central part of a short and robust scapula that is too fragmentary to be used for diagnostic purposes.

All humeri in the sample are clearly asymmetrical. The presence of the medial and lateral epicondyles cannot be ascertained for those specimens in which only the shaft is preserved (e.g., UMNH 18512, Fig. 9z; UMNH 18541, Fig. 9bb). It also seems that the medial and lateral cristae are poorly developed. The preserved distal part of UMNH 18214 (Fig. 9dd) is small and lacks the larger part of the caput, but its lateral epicondyle is completely absent (although the lateral crista is well developed, delimiting a large depression with the fossa cubitalis; the latter is represented by a deep groove adjacent to the caput). The medial epicondyle apparently did not reach distally to the same level as the caput. UMNH 18204 is only a proximal section of the humerus. Its ventral crista is prominent, extending onto the epiphysis. UMNH 18216 (Fig. 9aa-1,2) is apparently the humerus of a juvenile, in which the caput was not ossified and therefore not preserved. Both the medial and lateral cristae are only moderately developed. Asymmetry of the distal part of the bone is, however, apparent (it seems that the caput has shifted laterally), and the crista ventralis is present (marked by arrow in Fig. 9aa-1). The humerus UMNH 18223 (Fig. 9cc) is similar to UMNH 18216 in that it has both cristae only moderately developed (in fact, they are more or less rounded) and that its lateral epicondyle is entirely absent. The fossa cubitalis is well developed, as it is in other humeri. UMNH 18234, despite consisting of only the distalmost part of the bone, also represents a clearly asymmetrical humerus in which the lateral epicondyle is entirely lacking whereas the medial epicondyle is well developed and reaching the level of the distalmost margin of the caput. There is a deep incision between the caput and medial epicondyle.

None of the ilia in the sample has a dorsal tubercle. The ilium UMNH 18211 (Fig. 9o), although very small, may be characterized by a medium-sized acetabulum with only moderately elevated margins dorsally and anteriorly; anteroventrally, the margin of the acetabulum extends slightly beyond the outlines of the bone.

The ilium UMNH 18227 (Fig. 9k) is characterized by a relatively small acetabulum, the anteroventral margin of which is raised, so that the acetabulum is declined posteriorly. However, in other features it is similar to those ilia in the sample whose posterior part has a dorsal margin rising towards the pars ascendens. The ilia UMNH 18539 and 18213 (Fig. 9w and x, respectively) are basically similar to UMNH 18227 (Fig. 9k), except they are larger. UMNH 19293 (Fig. 9l) also resembles UMNH 18227, but differs in its large acetabulum that extends to or slightly beyond the anteroventral outline of the bone.

The ilia UMNH 18218 (Fig. 9p) and 18224 are characterized by their almost straight dorsal margin and by an acetabulum that is a mere depression in the bone, rather than a structure with elevated margins. UMNH 18218 (Fig. 9p) is a small ilium that could belong to a juvenile, but judging by other ilia of the same size in this sample (UMNH 18221 and 18233; Fig. 9n and t, respectively) its general morphology corresponds to that of adults. UMNH 18224 is similar in that its dorsal margin is nearly straight and the acetabulum is a relatively small depression with low margins.

The ilia UMNH 18228 (Fig. 9s) and 18233 (Fig. 9t) each have a comparatively large and triangular acetabular region that gradually tapers into the iliac shaft. Their acetabula are only shallow depressions in the bone. UMNH 18228 has its pars ascendens markedly extended posterodorsally.

UMNH 18229 (Fig. 9i), 18231 (Fig. 9j) and, perhaps, 19356 (Fig. 9r) and 19358 are similar to one another in having the proximal part of their shaft straight, with an elongated depression on its outer surface. At the posterior end of this depression, there is a small foramen (marked by arrow in Fig. 9i). The acetabulum is large, reaching anteroventrally beyond the outlines of the bone.

The ilia UMNH 18220 (Fig. 9u), 18221 (Fig. 9n) and, possibly, 18230 are characterized by having the dorsal margin of the acetabular region declined posteriorly towards the pars ascendens (the latter is considerably declined posterodorsally) and separated from the dorsal margin of the iliac shaft by a broad depression, and in having a large acetabulum whose anteroventral portion extends beyond the outlines of the bone. The upper margin of the bone is broadly rounded, with no trace of an oblique groove crossing over the dorsal margin. Because the anterior portion of the acetabulum is raised, it is facing posterolaterally, rather than laterally. UMNH 18222 is similar, but larger.

UMNH 19355 (Fig. 9m) is intermediate between UMNH 18220 (Fig. 9u) and 18221 (Fig. 9n) because it also has a large and probably triangular acetabular region, and between UMNH 18229 (Fig. 9i) and 18231 (Fig. 9j) in having a prominent though rounded ledge running from the dorsal margin of the acetabulum anteriorly and slightly ventrally on the shaft. The shaft is comparatively slender.

UMNH 18212 (Fig. 9v), although its size fits within the range of variation of other small anuran ilia, is anomalous. The shaft and presumed acetabulum are somewhat distorted; these may be a result of a healed injury or developmental malformation.

Late Santonian (Fig. 10A, B)

Straight Cliffs Formation, Hat Shop Aquatic, locality 569; Hat Shop, locality 420; North Side of Pasture Wash, localities 424 and 427

Material:

1 premaxilla (18482, Fig. 10Bgg-1,2); 9 maxillae (18401, Fig. 10Aa-1,2; 18402–18407; 19341, Fig. 10Ab-1,2; 19342, Fig. 10Ac-1,2); 2 prearticulars (18318, Fig. 10Ae-1,2; 18492, Fig. 10Ad); 6 trunk vertebrae (18386, Fig. 10Al-1–3; 18388, Fig. 10Am-1–3; 18390, Fig. 10Ak-1,2; 18392, Fig. 10Ah-1,2; 18470, Fig. 10Ai-1–3; 18472, Fig. 10Aj-1–4); 2 sacral vertebrae (18391, Fig. 10Ag-1,2; 18500, Fig. 10Af-1–3); 2 urostyles (18384, Fig. 10Bcc-1–3; 18385, Fig. 10Bdd-1–3); 1 scapula (18491, Fig. 10Bff-1,2); 18 humeri (18317; 18397, Fig. 10Bx; 18398; 18399, Fig. 10Bq; 18400, Fig. 10Bn; 18453; 18454, Fig. 10Bu; 18455, Fig. 10Bs; 18456, Fig. 10Bv; 18469, Fig. 10Bt; 18478, Fig.10Bm; 18481, Fig. 10Br; 18488–18490; 18503, Fig. 10Bo; 18504, Fig. 10Bw; 18505, Fig. 10Bp); 8 radioulnae (18464, 18465, 18468, 18493–18497); 18 ilia (18314, Fig. 10Bz-1,2; 18344, Fig. 10Bd-1,2; 18394, Fig. 10Ba-1,2; 18395, Fig. 10Bc-1,2; 18396, Fig. 10Bbb-1–3; 18471, Fig. 10Bb-1,2; 18473, Fig. 10Baa-1,2; 18474, Fig. 10Bi; 18475, Fig. 10Bg; 18476, Fig. 10Bk; 18477, Fig. 10Be; 18479, Fig. 10Bf; 18480, Fig. 10Bh; 18483, Fig. 10Bj; 18484, Fig. 10Bl; 18486; 18499; 18506, Fig. 10By;); 1 pair of ischia (18501, Fig. 10Bee); 4 femora (18316; 18459; 18463; 18466); 7 tibiofibulae (18315; 18393; 18460–18462; 18467; 18498).

Description:

The premaxilla UMNH 18482 (Fig. 10Bgg-1,2) is smooth on its outer surface, with only a short and widely rounded frontal process that was connected by a suture with its counterpart from the opposite side of the skull. On its inner surface, there is a thin horizontal lamina that broadens laterally.

The maxilla UMNH 18401 (Fig. 10Aa-1,2) belonged to a much larger frog. Its posterior process is broken off; however, its zygomaticomaxillar process seems to be preserved in its original shape (i.e. with a straight horizontal margin). The pterygoid process is directed medially, rather than posteriorly, and the horizontal lamina connecting its tip with the inner vertical surface of the bone is pierced by a foramen (see arrow in Fig. 10Aa-1). The sculpture on the outer surface of the bone tends to be tubercular, rather than pit-and-ridge. UMNH 18402 is the anterior part of the similar-sized maxilla, but with the dorsal margin broken off. Its outer surface is nearly smooth, except for few horizontal grooves along the lower part of the bone.