Abstract

This paper analyses the effect of increasing female participation in the labour market on the transition to first childbirth. Regional perspectives are considered to help us understand how postponement behaviour is changing over time and at different paces in each region. The analysis is based on the first wave of the Generations and Gender Survey of Italy and Hungary. We use a multilevel event history random intercept model to examine the effect of individuals’ positions in the labour market on the transition to motherhood, controlling for differences in macrolevel factors related to regional backgrounds in the two countries. The regional data for Italy came from the Italian National Statistical Institute, and for Hungary from our imputation developed from the time series available at the national and the regional levels (Hungarian Central Statistical Office, KSH). The postponement of first childbirth is strongly linked to the increasing involvement of women in paid work, but with opposite effects in the two countries. Even if we control for changes in women’s levels of education over time and for shifts in women’s aspirations and levels of attainment in the labour market, we find that being employed remains a risk factor for the postponement of the first birth among Italian women, and a strong protective factor among Hungarian women. At the contextual level, the variables that take into account the regional socio-economic changes provides evidence of important effects on individual behaviour among Italian women, and of only minor effects among Hungarian women. All of the regional breakdowns in both Italy and Hungary show that the postponement of motherhood goes hand-in-hand with the acceptance of deep cultural and socio-economic changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

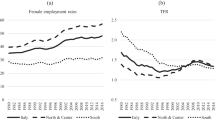

The European countries with the lowest fertility levels also have relatively low levels of female participation in the labour force, while countries with higher fertility levels tend to have relatively high female labour force participation rates.

For a review of the ‘work-family conflict’ literature see Voydanoff (1988).

The high percentages of youth unemployment and the low female labour market participation rate in many southern European countries, such as Italy, Greece, and Spain, seems to confirm the negative relationship between unemployment and fertility.

The distinction was based on the European Values Study data from 1999 published in Halman (2001).

Data show that in Italy in 2009 only 1.6 % of GDP was spent on family and motherhood, compared to the EU average of 2.6 %. The percentage of GDP spent on childcare in Hungary in 2009 was lower than the EU average, but greater than the share in Italy (2.2 %).

We calculated male rates using data form KSH MEF and ISTAT. The gender gaps are not presented here for space limits.

The young unemployment rates are been calculated using the same sources of data. They are not presented here for space limits.

As Spéder (2006) pointed out the age women had in 1990 is particularly important in understanding behavioural changes in a former socialist society such as Hungary.

See the “Appendix” for the classification of regional variables used both for Italy and Hungary.

To test whether the effect of age varies across regions, we used a likelihood ratio test in which the null hypothesis was that the two new parameters (u 0j and u 1j ) in the first model were simultaneously equal to zero. The likelihood ratio test statistic was calculated with and without the random slope for age. We could therefore conclude that the effect of age did indeed vary across regions.

To describe the changes in the reproductive behaviour of different individuals who grew up during the same period with similar historical experiences and opportunities, the women were grouped into five-year generations.

Details on how the covariates are built are available in the “Appendix”.

It should be noted that since this is a discrete-time logit model, there is a second-level, regional error (u 0j ) associated with the model, but none at the individual level (cf. Hox 2002).

For example, for a woman born in 1977 who reached age 13 in 1990, we assigned the percentage of the women with secondary education recorded in 1990 for the first year in which they are at risk of first motherhood, that of 1991 for the second year, and so on; whereas for a second woman born in 1970 who reached age 13 in 1983, the percentage of women with secondary education will be that of 1983 for the first year, 1984 for the second year, and so on.

We are conscious that fertility support policies have a strong effect on the postponement of first motherhood, and that these policies differ greatly between the two countries: until 1990, Hungary maintained its fertility rate thanks to numerous policies that were modified in the 1990 s [for a brief survey of Hungarian policies on the family and fertility, see UNECE 1998], while Italy’s policy actions in this area were sporadic and ineffective. Unfortunately, due to the lack of data, we were not able to include in the model any data on this topic.

All estimation was done with the multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression (xtmelogit) in STATA.

The estimates related to Models 1, 2, and 3, produced with a stepwise procedure, are shown in the “Appendix”.

It is based on a linear predictor that includes both the fixed effects and the random effects, and the predicted mean is conditional on the values of the estimated random effects.

The selection of regions was based on their estimated means, also incorporating the random effects.

Aassve at al. (2006b) argued that when fertility and partnership formation and living in the parental home are very closely interrelated, considering partnership status only as a covariate in the fertility equation also captures the influence that some other covariates have on fertility, thus biasing the estimates of interest. To avoid this potential problem of endogeneity, we conducted a sensitive analysis, excluding the marital status and the living in the parental home variables, which strengthened the credibility of our results for both Italy and Hungary.

References

Aassve, A., Billari, F. C., & Spéder, Z. (2006a). Societal transition, policy changes and family formation: Evidence from Hubeckerngary. European Journal of Population, 22(2), 127–152.

Aassve, A., Burgess, S., Propper, C., & Dickson, M. (2006b). Employment, family union and childbearing decisions in Great Britain. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 169(4), 781–804.

Adserà, A. (2004). Changing fertility rates in developed countries. The impact of labour market institutions. Journal of Population Economics, 17, 17–43.

Adserà, A. (2011a). Where are the babies? Labor market conditions and fertility in Europe. European Journal of Population, 27, 1–32.

Adserà, A. (2011b). The interplay of employment uncertainty and education in explaining second births in Europe. Demographic Research, 25(16), 513–544.

Ahn, N., & Mira, P. (2002). A note on the changing relationship between fertility and female employment rates in developed countries. Journal of Population Economics, 15, 667–682.

Allison, P. D. (1984). Event history models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Press.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & Kimmel, J. (2005). The motherhood wage gap for women in the United States: The importance of college and fertility delay. Review of Economics of the Household, 3(1), 17–48.

Axinn, W. G., Clarkberg, M. E., & Thornton, A. (1994). Family influences on family size preferences. Demography, 31, 65–79.

Becker, G. S. (1973). A theory of marriage: Part I. The Journal of Political Economy, 81, 813–846.

Becker, G. S. (1981). A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Becker, G., & Lewis, H. G. (1973). On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. The Journal of Political Economy, 81, S279–S288.

Begall, K. H., & Mills, M. (2012). The impact of occupation and occupational sex segregation on fertility in the Netherlands. European Sociological Review, doi: 10.1093/esr/jcs051.

Benjamin, K. (2001). Men, women, and low fertility: Analysis across time and country. Unpublished Working Paper: University of North Carolina.

Berent, J. (1953). Relationship between family sizes of the successive generations. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly Bulletin, 31, 39–50.

Bernhardt, E. (1993). Fertility and employment. European Sociological Review, 9, 25–42.

Billari, F. C. (2008). Lowest-low fertility in Europe: Exploring the causes and finding some surprises. The Japanese Journal of Population, 6(1), 2–18.

Billari, F. C., & Kohler, H. P. (2004). Patterns of low and very low fertility in Europe. Population Studies, 58(2), 161–176.

Blossfeld, H. P., & Huinink, J. (1991). Human capital investments or norms of role transition? How women’s schooling and career affect the process of family formation. The American Journal of Sociology, 97(1), 143–168.

Blossfeld, H. P., & Rohwer, G. (2001). Techniques of event history modelling. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bongaarts, J., & Feeney, G. (1998). On the quantum and tempo of fertility. Population and Development Review, 24(2), 271–291.

Breen, R. (1997). Risk, recommodification and stratification. Sociology, 31(3), 473–489.

Breen, R. (2005). Explaining cross-national variation in youth unemployment: Market and institutional factors. European Sociological Review, 21(2), 125–134.

Brewster, K. L., & Rindfuss, R. R. (2000). Fertility and women’s employment in industrialized nations. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 271–296.

Caltabiano, M., Castiglioni, M., & Rosina, A. (2009). Lowest-low fertility: Signs of a recovery in Italy? Demographic Research, 23, 681–718.

Coleman, D. (2006). Immigration and ethnic change in low-fertility countries: A third demographic transition? Population and Development Review, 32(3), 401–446.

d’Addio, A. C., & Mira d’Ercole, M. (2005). Trends and determinants of fertility rates in OECD countries: The role of policies. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, 27.

Dalla Zuanna, G., & Tanturri, M. L. (2007). Veneti che cambiano. La popolazione sotto la lente di quattro censimenti. Verona: CIERRE.

de Laat, J., & Sevilla-Sanz, A. (2011). Working women, men’s home time and lowest low fertility. Feminist Economics, 17(2), 87–119.

De Rose, A., Racioppi, F., & Zanatta, A. L. (2008). Italy: Delayed adaptation of social institutions to changes in family behaviour. Demographic Research, Special Collection, 7(19), 665–704.

De Sandre, P., Ongaro, F., Rettaroli, R., & Salvini, S. (1997). Matrimonio e figli: tra rinvio e rinuncia. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Del Boca, D. (1998). Labor policies, economic flexibility and women’s work: The Italian experience. In E. Drew & R. Emerek (Eds.), Women’s work and labor markets. London/New York: Routledge Press.

Del Boca, D. (2002a). Low fertility and labour force participation of Italian women: Evidence and interpretations. OECD Labour Market and Social Policy Occasional Papers 61, OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/263482758546.

Del Boca, D. (2002b). The effect of child care and part time on participation and fertility of Italian women. Journal of Population Economics, 15(3), 549–573.

Del Bono, E. (2001). Estimating the fertility responses to expectations: Evidence from the 1958 British cohort. Discussion paper, No. 80, University of Oxford.

Easterlin, R. (1976). Population change and farm settlement in the Northern United States. Journal of Economic History, 36(1), 45–75.

Engelhardt, H., Kögel, T., & Prskawetz, A. (2001). Fertility and employment reconsidered. A time series macro-level analysis. Rostock: Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research.

Engelhardt, H., & Prskawetz, A. (2004). On the changing correlation between fertility and female employment over space and time. European Journal of Population, 20, 35–62.

Ermisch, J. (1999). Prices, parents, and young people’s household formation. Journal of Urban Economics, 45(1), 47–71.

Esping-Andersen, G. (2009). The incomplete revolution. Adapting to women’s new roles. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Eurostat. (2012). Population data. Downloaded from: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/statistics/search_database.

Ferge, Z. (1997). Women and social transformation in Central-Eastern Europe. Czech Sociological Review, 5(2), 159–178.

Fodor, E. (2005). Women at work. Hungary and Poland. United Nations Research Institute for Social Development: The status of women in the labour markets of the Czech Republic. Occasional Paper 3.

Frejka, T. (2008). Determinants of family formation and childbearing during the societal transition in Central and Eastern Europe. Demographic Research, 19(7), 139–170.

Frejka, T., & Sardon, J. P. (2007). Cohort birth order, parity progression ratio and parity distribution trends in developed countries. Demographic Research, 16, 315–374.

Frejka, T., & Sobotka, T. (2008). Overview chapter 1: Fertility in Europe: Diverse, delayed and below replacement. Demographic Research, 19(3), 15–46.

Gabrielli, G., & Hoem, J. M. (2010). Italy’s non-negligible cohabitational unions. European Journal of Population, 26(1), 33–46.

Goldstein, H. (2003). Multilevel statistical models (3rd Edition ed.). London: Edward Arnold.

Goldstein, J. R., Sobotka, T., & Jasilioniene, A. (2009). The end of lowest-low fertility? Population and Development Review, 35(4), 663–700.

Gustafsson, S. (2001). Optimal age at motherhood. Theoretical and empirical considerations on postponement of maternity in Europe. Journal of Population Economics, 14(2), 225–247.

Gustafsson, S., & Kalwij, A. S. (2006). Education and postponement of maternity: Economic analysis for industrialized countries (Kluwer Academic Publishers, European Studies of Population, 15). Dordrecht: Springer.

Halman, L. (2001). The European values study. A third wave. Tilburg: EVS, WORC, Tilburg, University.

Happel, S. K., Hill, J. K., & Low, S. A. (1984). An economic analysis of the timing of childbirth. Population Studies, 38(2), 299–311.

Hotz, V. J., & Miller, R. A. (1988). An empirical analysis of life cycle fertility and female labor supply. Econometrica, 56(1), 91–118.

Hox, J. J. (1995). Applied multilevel analysis. Amsterdam: TT-Publikaties.

Hox, J. J. (2002). Multilevel analysis. Techniques and applications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Human Fertility Database. (2013). Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany) and Vienna Institute of Demography (Austria). www.humanfertility.org (data downloaded on March 16, 2013).

Inglehart, R. (1977). The silent revolution: Changing values and political styles among western publics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Istat. (2003). Indagine multiscopo su famiglie e soggetti sociali (Family and social subjects). Rome.

Joshi, H. (2002). Production, reproduction and education: Women, children and work in a British perspective. Population and Development Review, 28, 445–474.

Kapitány, B. (2003). Turning points of the life course. Sampling, reliability of the raw data, http://www.demografia.hu/letoltes/dpa/panel1_minta_a.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2012.

Kerckhoff, A. C. (1995). Institutional arrangements and stratification processes in industrial societies. Annual Review of Sociology, 15, 323–347.

Klijzing, E. (2005). Globalization and the early life course. In H.-P. Blossfeld, E. Klijzing, M. Mills, & K. Kurz (Eds.), Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society (pp. 25–49). London/New York: Routledge.

Kögel, T. (2004). Did the association between fertility and female employment within OECD countries really change its sign? Journal of Population Economics, 17(1), 45–65.

Kohler, H. P., Billari, F. C., & Ortega, J. A. (2002). The emergence of lowest- low fertility in Europe during the 1990s. Population and Development Review, 28(4), 641–681.

Kravdal, Ø. (1992). The emergence of a positive relation between education and third birth rates in Norway with supportive evidence from the United States. Population Studies, 46(3), 459–475.

Kreyenfeld, M. (2010). Uncertainties in female employment careers and the postponement of parenthood in Germany. European Sociological Review, 26(3), 351–366.

Kulu, H. (2011). Why do fertility levels vary between urban and rural areas? Regional Studies, 47(6), 895–912.

Kulu, H., & Boyle, P. J. (2009). High fertility in city suburbs: Compositional or contextual effects? European Journal of Population, 25(2), 157–174.

Lesthaeghe, R., & Moors, G. (2000). Recent trends in fertility and household formation in the industrialized world. Review of Population and Social Policy, 9, 121–170.

Lesthaeghe, R., & Surkyn, J. (1988). Cultural dynamics and economic theories of fertility change. Population and Development Review, 14(1), 1–45.

Macunovich, D. J. (1996). Relative income and price of time: Exploring their effects on US fertility and female labor force participation. Population and Development Review, 22, 223–257.

Marini, M. M., & Hodsdon, P. J. (1981). Effects of the timing of marriage and first birth of the spacing of subsequent births. Demography, 18(4), 29–48.

Martin, S. P. (2000). Diverging fertility among U.S. women who delay childbearing past age 30. Demography, 37, 523–533.

Matysiak, A. (2011). Interdependencies between fertility and women’s labour supply. Dordrecht: Springer.

Matysiak, A., & Vignoli, D. (2009). Finding the ‘right moment’ for the first baby to come: A comparison between Italy and Poland. MPIDR, Working paper WP 2009.011 of the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research.

McDonald, P. (2000). Gender equity in theories of fertility transition. Population and Development Review, 26(3), 427–439.

Miller, A. R. (2010). The effect of motherhood timing on career path. Journal of Population Economics, 24(3), 1071–1100.

Mills, M., & Blossfeld, H. P. (2005). Globalization, uncertainty and changes in early life courses. In H.-P. Blossfeld, E. Klijzing, M. Mills, & K. Kurz (Eds.), Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society (pp. 1–24). London/New York: Routledge.

Morgan, S. P., Ronald, R., & Rindfuss, R. R. (1999). Reexamining the link of early childbearing to marriage and to subsequent fertility. Demography, 36, 59–75.

Müller, W. (2005). Education and youth integration into European labour markets. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 46, 461–485.

Murphy, M., & Wang, D. (2001). Family-level continuities in childbearing in low-fertility societies. European Journal of Population, 17, 75–96.

Ongaro, F. (2002). Low fertility in Italy between explanatory factors and social and economic implications: Consequences for the research. In Proceedings XLI Riunione Scientifica della SIS (Sessioni plenarie e specializzate). Padua: Cleup.

Oppenheimer, V. K. (1988). A theory of marriage timing. The American Journal of Sociology, 94(3), 563–591.

Oppenheimer, V. K. (1994). Women’s rising employment and the future of the family in industrial societies. Population and Development Review, 20(2), 293–342.

Oppenheimer, V. K. (2003). A gender perspective on preferences for marriage among cohabiting couples. Demographic Research, 15, 311–328.

Oppenheimer, V. K., Kalmijn, M., & Lim, N. (1997). Men’s career development and marriage timing during a period of rising inequality. Demography, 34, 311–330.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation, Development (OECD). (2012). OECD family database. Paris: OECD.

Pinnelli, A., & Di Giulio, P. (1999). Sistema di genere, famiglia e fecondità nei paesi sviluppati. In P. De Sandre, A. Pinnelli, & A. Santini (Eds.), Nuzialità e fecondità in trasformazione: Percorsi e fattori del cambiamento. Bologna: il Mulino.

Rindfuss, R. R., & Brauner-Otto, S. R. (2008). Institutions and the transition to adulthood: Implications for fertility tempo in low-fertility settings. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 6, 57–87.

Rindfuss, R., Bumpass, L., & John, C. S. (1980). Education and fertility: Implications for the roles women occupy. American Sociological Review, 45, 431–447.

Rindfuss, R. R., Guzzo, K. B., & Morgan, S. P. (2003). The changing institutional context of low fertility. Population Research and Policy Review, 22, 411–438.

Rindfuss, R., & VandenHeuvel, A. (1990). Cohabitation: A precursor to marriage or an alternative to being single? Population and Development Review, 16, 703–726.

Roberts, A. (2008). The influences of incident and contextual characteristics on crime clearance of nonlethal violence: A multilevel event history analysis. Journal of Criminal Justice, 36, 61–71.

Rosina, A., & Fraboni, R. (2004). Is marriage losing its centrality in Italy? Demographic Research, 11(6), 149–172.

Rosina, A., & Testa, M. R. (2007). Senza figli: Intenzioni e comportamenti italiani nel quadro europeo. Rivista di Studi Familiari, 12(1), 71–81.

Santarelli, E. (2011). Economic resources and the first child in Italy: A focus on income and job stability. Demographic Research, 25(9), 311–336.

Schultz, T. W. (1974). The high value of human time: Population equilibrium. Journal of Political Economy, 82(2), S2–S10.

Singer, J. D., & Willett, J. B. (1993). It’s about time: Using discrete-time survival analysis to study duration and the timing of events. Journal of Educational Statistics, 18, 155–195.

Singer, J. D., & Willett, J. B. (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modelling change and event occurrence. Oxford: University Press.

Sobotka, T. (2003). Re-emerging diversity: Rapid fertility changes in Central and Eastern Europe after the collapse of the Communist Regimes. Population, 58(4–5), 451–485.

Sobotka, T. (2004). Postponement of childbearing and low fertility in Europe. Doctoral thesis, University of Groningen. Amsterdam: Dutch University Press.

Sobotka, T., Zeman, K., & Kantorová, V. (2003). Demographic shifts in the Czech Republic after 1989: A second demographic transition view. European Journal of Population, 19(3), 249–277.

Spéder, Z. (2001). Turning points of the life course. Concept and design of the Hungarian social and demographic panel survey. Demográfia, 44(2–3), 305–320. (English Edition).

Spéder, Z. (2005). The rise of cohabitation as first union and some neglected factors of recent demographic developments in Hungary. Demográfia, 48, 77–103. (English Edition).

Spéder, Z. (2006). Rudiments of recent fertility decline in Hungary: Postponement, educational differences, and outcomes of changing partnership forms. Demographic Research, Descriptive Finding, 15(8), 253–288.

Spéder, Z., & Kamaràs, F. (2008). Hungary: Secular fertility decline with distinct period fluctuations. Demographic Research, 19(18), 599–664.

Steele, F. (2008). Multilevel models for longitudinal data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (Statistics in Society), 171, 5–19.

Surkyn, G., & Lesthaeghe, R. (2004). Value orientations and the second demographic transition in northern, western and southern Europe: An update. Demographic Research, 3(3), 45–86.

Svejnar, J. (2002). Transition economies: Performance and challenges. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(1), 3–28.

Sweeney, M. M. (2002). Two decades of family change: The shifting economic foundations of marriage. American Sociological Review, 67(1), 132–147.

Taniguchi, H. (1999). The timing of childbearing and women’s wages. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61(4), 1008–1019.

Teachman, J., & Crowder, K. (2002). Multilevel models in family research: Some conceptual and methodological issues. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(2), 280–294.

UNECE. (1998). National report of Hungary, The regional population meeting, Budapest (Hungary), December 7–9, 1998.

Van Bavel, J. (2010). Choice of study discipline and the postponement of motherhood in Europe: The impact of expected earnings, gender composition and family attitudes. Demography, 47, 439–458.

van De Kaa, D. J. (1987). Europe’s second demographic transition. Population Bulletin, 42(1), 1–59.

Vignoli, D. (2008). Work and fertility. Employment and reproductive careers among Italian couples. Doctoral thesis. Rome: La Sapienza University.

Vignoli, D., Drefahl, S., & De Santis, G. (2012). Whose job instability affects the likelihood of becoming a parent in Italy? A tale of two partners. Demographic Research, 26(2), 41–62.

Vignoli, D., & Ferro, I. (2009). Rising marital disruption in Italy and its correlates. Demographic Research, 20(4), 11–36.

Voydanoff, P. (1988). Work role characteristics, family structure demands, and work/family conflict. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50, 749–761.

Wallace, C. (Ed.) (2003). Country contextual reports—Demographic trends, labour market and social policies. HWF Research Report 2, Vienna: Institute for Advanced Studies.

Willett, J. B., & Singer, J. D. (1995). It’s deja vu all over again: Using multiple-spell discrete-time survival analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 20(1), 41–67.

Willis, R. J. (1973). A new approach to the economic theory of fertility behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 81(2), S14–S64.

Windzio, M. (2006). The problem of time dependent explanatory variables at the contest-level in discrete time multilevel event history analysis: A Comparison of models considering mobility between local labour markets as an example. Quality & Quantity, 40, 175–185.

Wolbers, M. H. J. (2007). Employment insecurity at labour market entry and its impact on parental home leaving and family formation. A comparative study among recent graduates in eight European countries. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 48(6), 481–507.

Yamaguchi, K. (1991). Event history analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Zimmer, B. G., & Fulton, J. (1980). Size of family, life chances, and reproductive behaviour. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 42, 657–670.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their extremely useful comments, which have helped us to significantly improve the paper, and Giovanni Boscaino for helping with the regional maps of Hungary and Italy. The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by University of Palermo [Grant No. ORPA06YH89 under the responsibility of Ornella Giambalvo]. Although this paper is the result of the joint effort of both authors, introduction and lowest-low fertility sections are attributable to O. Giambalvo whereas all the other sections to A. Busetta.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Data

Appendix: Data

Micro-dimension (individual variables)

- Age:

-

Calculated from the difference between the month and the year of the interview and the interviewee’s year and month of birth

- Regional Area:

-

For Hungary the regional variable is the result of cross-classification of the type of settlement (classified as capital, city, town, and village) and the Nuts 2 region where women lived, whereas for Italy is it simply the Nuts 3 (note that the survey does not allow for the consideration of regional and municipal levels simultaneously)

- Generation:

-

We grouped women born from 1967 to 1981 into five-year age groups according to their age at the start of the political transition (i.e., 1990), as was proposed by Spéder (2005) (see Scheme 1). To compare the information provided by the two surveys and to describe the differences and similarities in the changes observed in reproductive behaviour for various cohorts, we also used Spéder’s classification to group Italian women

Scheme 1—Respondents’ year of birth, age at interview, and age in 1990

Year of birth

Age at interview

Age in 1990 (year)

1967–1971

30–34

19–23

1972–1976

25–29

14–18

1977–1981

20–24

9–13

- Leaving parental home:

-

In both surveys, the information regarding the time of leaving the parental home was not assessed exactly. The age/year at ‘leaving the parental home’ was defined only for women for whom the change of family or home did not coincide with the time of first marriage or first cohabitation

- Marriage and cohabitation:

-

For the purposes of the analysis, only the first marriage or first cohabitation was considered

- Level of education:

-

The year in which the level of study was achieved was classified as follows: ‘no qualifications,’ ‘primary school,’ ‘professional school’ (only for Hungary, where vocational school lasts 1 year less than secondary school), ‘secondary school,’ or ‘university and beyond’). When interviewees provided their level of study but not the year, we considered it to correspond to the mean duration necessary to obtain the same qualifications in the country (calculated by the survey)

- Activity status:

-

For Italy we created a dichotomic variable with value 1 if in the t year the woman was in a job, or 0 otherwise. For Hungary the variable used was equal to 0 if we did not know her effective job position, 1 if she was not employed and 2 if the woman was in a job

- Parents:

-

The questions asked about family background were slightly different in the two surveys but it was therefore possible to deduce whether the parents were living together when the respondent was 15 years old

- Number of siblings:

-

The Italian survey asked how many brothers and sisters the interviewee had, while the Hungarian survey was concerned with the number of brothers and sisters with whom the interviewee was brought up

Macro-dimension (contextual variables)

Hungary

- Employment rate:

-

The time regional series from 1992 are available (Source: KSH MEF CSO Labour Force Survey). Using known time series we fitted a regressive linear model for the imputation of missing data (both for the year and regions)

- Unemployment rate:

-

The time regional series from 1992 are available (Source: KSH MEF CSO Labour Force Survey). To estimate the missing data, an increasing or decreasing rate was obtained as the rate of the average of the known data, and the average of the known data minus the last one (for the year and for regions) was used

- Female participation rate:

-

The time regional series from 1992 are available (Source: http://www.ksh.hu/docs/eng/xstadat/xstadat_long/h_qlf013a.html). To estimate the missing data an increasing or decreasing rate was obtained as the rate of the average of the known data, and the average of the known data minus the last one (for the year and for regions) was used

- Graduate female rate:

-

Using the GGS database, the number of female university graduates and the female/male rate was estimated. At the end, the female graduates and the females interviewed were calculated. Finally, this rate was used as an expansive rate for the entire female graduate population

- Secondary school female rate:

-

We adopt the same method for the point d. Starting with 1990 we used data available on http://www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xftp/idoszaki/pdf/kozoktter03.pdf

Italy

- Employment rate:

-

The time regional series are available (Source: ISTAT, http://dati.istat.it/). Using known time series for 1975 and 1976, the rates were estimated using the average imputation method considering data of 5 years

- Unemployment rate:

-

The time regional series are available (Source: ISTAT, http://dati.istat.it/). Using known time series for 1975 and 1976, the rates were estimated using the average imputation method considering data of 5 years

- Female participation rate:

-

The time regional series are available (Source: ISTAT, http://dati.istat.it/). Using known time series for 1975 and 1976, the rates were estimated using the average imputation method considering data of 5 years

- Graduate female rate:

-

Svimez DATA are available since 1996. We estimated the missing data using the following method: \( y_{t} = y_{t - 1} + \frac{{(y_{t + 1} - y_{t - 1} )}}{2} \). Sampling data from ISTAT graduate placement surveys are used for the regional distributions

- Secondary school female rate:

-

We adopted the same method for the graduate female rate

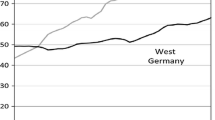

Transition to the first birth by generation in Italy and in Hungary. Source: (left) Istat 2003 survey Family and Social Subjects; (right) Hungarian Central Statistical Office—Demographic Research Institute, 2001–2002 survey Turning point of the life course

Transition to the first birth by regions (NUT2), by generation in each region in Italy. Source: Istat 2003 survey Family and Social Subjects

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Busetta, A., Giambalvo, O. The effect of women’s participation in the labour market on the postponement of first childbirth: a comparison of Italy and Hungary. J Pop Research 31, 151–192 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-014-9126-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-014-9126-4