Abstract

In 2004, at a time when the nation was experiencing the lowest fertility trends in its history, the Australian Federal Government introduced the offer of a cash payment of $3,000 to all women on the birth of a new baby. The maternity payment, commonly known as the baby bonus, was increased to $4,000 in 2006 and to $5,000 in 2008. While not explicitly declared a pronatalist policy at the time of its introduction, the baby bonus was later credited with helping to halt the decline of the nation’s aggregate birth rates. This paper examines the effect of this policy on Australian women’s childbearing intentions from 2001 to 2008, using panel data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics (HILDA) Survey. The results indicate that the introduction of the baby bonus coincided with a statistically significant increase in women’s childbearing intentions. More specifically, the strongest increase occurred among women from lower-income households, potentially implying that the policy had the strongest effect on women who, given their current characteristics, are relatively likely to be reliant on welfare assistance to raise their children over the long term. The inferences drawn from the paper’s findings raise concern over the capacity of the baby bonus policy to reduce aggregate dependency rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

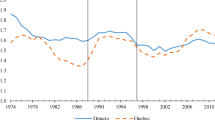

Australia’s total fertility rate (the average number of children that each woman bears during her lifetime) had been below the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman since the mid-1970s. It declined continually during the 1990s, and reached its lowest level of 1.73 children per woman in 2001 (ABS various years).

The birth rate measures the number of births per 1,000 people in the total population (ABS various years).

In response to these concerns, the Australian Government later replaced the lump-sum payment with a system of fortnightly instalments paid over 6 months. This system applied only to recipients under the age of 18 years from 2007, but was extended to all recipients from 2009 (FAHCSIA 2010 ).

In possible relation to this concern, from 2009, the baby bonus payment was no longer offered to families with a combined taxable income over $75,000 in the six-month period after the birth (FAHCSIA 2010 ).

An oversight of these arguments, however, is that women’s postponement of childbearing carries a higher risk of unrealized intentions, since the chances of normal conception and healthy delivery decline with a mother’s age. While a 25-year-old woman has almost 25% chance of becoming pregnant within a given month, this rate falls to 20% by age 30, 15% by age 36, 7% by age 40, and less than 1% by age 45 (Cranstoun and Harrison 2005; Sydney IVF 2005).

Unless otherwise specified, an increase in women’s average childbearing intentions refers to an increase in the share of respondents who stated that they were either ‘likely’ or ‘very likely’ to have children in the future, as reported in Appendix Table 4 .

Although women with undergraduate levels of education reported a decline in the share of ‘likely’ and ‘very likely’ responses in this year, this was accompanied by a larger decrease in the share of ‘unlikely’ and ‘very unlikely’ responses.

Although women from households with an annual income of $0 < $50,000 reported a decline in the share of ‘likely’ and ‘very likely’ responses in this year, this was accompanied by a larger decrease in the share of ‘unlikely’ and ‘very unlikely’ responses.

In Table 1, a response of 0 or 1 has been classified as ‘very unlikely’; 2, 3, or 4 has been classified as ‘unlikely’; 5 has been classified as ‘neutral’; 6, 7 or 8 has been classified as ‘likely’; and 9 or 10 has been classified as ‘very likely’.

Questions relating to childbearing intentions were asked of women of all ages in all years of the HILDA survey except for the 2005 survey which only asked women aged 18 to 44 years. Additionally, women who report an inability to have children due to medical reasons were identified only in the 2005 survey. For these reasons, the total sample for analysis only includes the observations of women aged 18 to 44 years who were present in the 2005 survey and indicated that they did not have an inability to have children. This restriction has the effect of reducing the sample representation of women aged 41 to 44 years in 2001, 42 to 44 years in 2002, 43 or 44 years in 2003, 44 years in 2004, 18 years in 2006, 18 or 19 years in 2007, or 18 to 20 years in 2008. Results are interpreted with this restriction in mind.

When re-estimated in 2007, the cost of raising a child up to four years of age was estimated to be $144 per week for an average household, tallying to $7,488 per year (Percival et al. 2007, p. 9). The baby bonus payment of $4,000 in 2006 would therefore cover the cost of raising a child for approximately the first 27 weeks of the child’s life. When lifted to $5,000 in 2008, the baby bonus payment would cover the cost of raising a child for approximately the first 34 weeks of the child’s life.

According to the NATSEM report, the weekly cost of raising a child increases as children grow older. The average cost of raising a child is estimated to increase to $164 per week for a child aged 5 to 9 years, $209 per week for a child aged 10 to 14 years, and $318 per week for a child aged 15 to 17 years (Percival and Harding 2002, p.3). These estimations apply to the cost of raising the first child, but it is acknowledged that the average cost per child declines as the number of children in the family increases, owing to shared overhead costs.

At the time that the baby bonus was introduced, paid maternity leave was a legislated entitlement for public sector employees, but only available to private sector employees at the discretion of their employer. In 2011, the Federal Government introduced a universal system of paid parental leave to all employed women while retaining the baby bonus for non-working women. From 2011, employed women have a choice between taking the baby bonus payment or paid parental leave. The government-funded component of paid parental leave is a flat-rate payment equivalent to the minimum wage ($570 as at 2011) paid for 18 weeks to women earning up to $150,000 per year (FaHCSIA 2010). Employers may offer paid maternity or parental leave in addition to this government-funded component.

References

Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). (2004). Economy will nurture population growth: Costello, Program Transcript, 9 December.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (various years). Births Australia, Cat. no. 3301.0.

Australian Medical Association Queensland (AMAQ). (2004). Baby you’re sending the wrong message, Media Release, 8 June.

Björklund, A. (2006). Does family policy affect fertility? Lessons from Sweden. Journal of Population Economics, 9, 3–24.

Bongaarts, J. (2008). What can fertility indicators tell us about pronatalist policy options? Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 6, 39–55.

Butler, J. S., & Moffitt, R. (1982). A computationally efficient procedure for the one-factor multinomial probit model. Econometrica, 50(3), 761–764.

Cooke, D. (2006). The pride of the nation: A new wave of baby boomers, The Age, 3 June, 1.

Costello, P. (2006). Doorstop interview, Interview transcript, treasury place, Melbourne, 2 June. http://www.treasurer.gov.au/DisplayDocs.aspx?doc=transcripts/2006/086.htm&pageID=004&min=phc&Year=2006&DocType=2. Accessed 14 November 2007.

Costello, P. (2007). Launch of the 2006 Census ABS data processing centre, speech transcript, Melbourne, 27 June. http://www.treasurer.gov.au/DisplayDocs.aspx?pageID=&doc=speeches/2007/011.htm&min=phc. Accessed 24 January 2008.

Cranstoun, J., & Harrison, K. (2005). Age and infertility, Article reproduced by Australian Infertility Support Group. http://www.nor.com.au/community/aisg/article03.htm. Accessed 5 February 2006.

Cronin, D. (2004). Costello’s baby boom on the way, Canberra Times, 8 December, 1.

d’Addio, A. C., & d’Ercole, M. M. (2005). Trends and determinants of fertility rates in OECD countries: The role of policies, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers.

Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FAHCSIA). (2010). Family Assistance Guide. http://www.fahcsia.gov.au/guides_acts/fag/fag-rn.html. Accessed 6 December 2010.

Dodson, L. (2004). The mother of all spending sprees; Budget 2004 Costello splurges $37bn on tax and families, pleads for baby boom, Sydney Morning Herald, 12 May, 1.

Drago, R., Sawyer, K., Sheffler, K., Warren, D., & Wooden, M. (2009). Did Australia’s baby bonus increase the fertility rate? Working Paper no. 1/09, Melbourne Institute of Applied Social and Economic Research, University of Melbourne.

Frechette, G. R. (2001). Random-effects ordered probit. STATA Technical Bulletin, 59, 23–27.

Gans, J. S., & Leigh, A. (2007) Born (again) on the first of July: Another experiment in birth timing, unpublished. http://works.bepress.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1014&context=joshuagans. Accessed 14 November 2007.

Gauthier, A. H., & Philipov, D. (2008). Can policies enhance fertility in Europe? Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, Vienna Institute of Demography, pp. 1–16.

Grattan, M., & Nguyen, K. (2004). Baby bonus tempts teens, claims Labor, The Age, 27 May, 1.

Guest, R. (2007). The baby bonus: A dubious policy initiative. Policy, 23, 11–16.

Houlihan, L. (2006). Warning to mums over baby bonus. Herald Sun, 19 June. http://www.news.com.au/story/print/0,10119,19512739,00.html. Accessed 14 November 2007.

Jones, K. (2005) Baby—let’s have a spending spree. Daily Telegraph, 4 June, 14.

Lain, S. J., Ford, J. B., Raynes-Greenow, C. H., Hadfield, R. M., Simpson, J. M., Morris, J. M., et al. (2009). The impact of the baby bonus payment in New South Wales: Who is having ‘one for the country’? Medical Journal of Australia, 190(5), 238–241.

Lattimore, R., & Pobke, C. (2008). Recent trends in Australian fertility. Productivity Commission Staff Working Paper, Canberra, July.

Lunn, S., & Wilson, L. (2008). Time to rethink baby bonus, The Australian, 14 March, 1, 6.

Maguire, T. (2004). Doctors warn: Don’t risk your baby for $3000, The Daily Telegraph, 18 June, 1.

Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (MIAESR). (2010). HILDA survey: Annual report 2009, The University of Melbourne.

Milligan, K. (2005). Subsidizing the stork: New evidence on tax incentives and fertility. Review of Economics and Statistics, 87(3), 539–555.

Millmow, A. (2006). One for mum, dad, the country… and the welfare bill. Canberra Times, 8 August, 15.

Percival, R., & Harding, A. (2002). All they need is love…and around $450,000. AMP-NATSEM Income and Wealth Report, Issue 3.

Percival, R., Payne, A., Harding, A., & Abello, A. (2007). Honey, I calculated the kids…It’s $537,000. AMP-NATSEM Income and Wealth Report, Issue 18.

Price, S. (2006). Doctors want premature start to baby bonus rise. The Age, 25 June, 3.

Silmalis, L. (2004). Fears baby bonus will be squandered: Money tempts unwary. The Sunday Telegraph, 27 June, 4.

Stata Press (2003). Cross-sectional time-series, Stata Reference Manual, Release 8, Stata Corporation, Texas.

Sydney IVF (2005). Age and infertility. http://www.sydneyivf.com/page.cfm?id=62. Accessed 5 February 2006.

Sydney Morning Herald (2006) Baby bonus creates hospital havoc, 18 June. http://www.smh.com.au/news/National/Baby-bonus-creates-hospitalhavoc/2006/06/18/1150569203159.html. Accessed 14 November 2007.

Tesfaghiorghis, H. (2006). Fertility, desires and intentions: A longitudinal analysis. Paper presented at Australian Population Association Conference, Adelaide, 6–8 December.

Treasury (2002). Intergenerational report, 2002–2003 Budget Paper No. 5, Commonwealth of Australia. http://www.budget.gov.au/2002-03/bp5/html/index. Accessed 18 Feb 2006.

Vieira, J. A. C. (2005). Skill mismatches and job satisfaction. Economic Letters, 89(1), 39-47.

Wells, R. (2004). Women decide: Give birth today or take the $3000? The Age, 30 June, 9.

Wilkins, R., Warren, D., Hahn, M., & Houng, B. (2010) Families, incomes and jobs, Volume 5: A statistical report on Waves 1 to 7 of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey, Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, The University of Melbourne.

Acknowledgment

Aspects of this paper’s analysis draw on the author’s PhD thesis An Economic Analysis of Maternity Leave Provisions in Australia (University of Queensland, 2008). The paper uses data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey, which is funded by the Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) and managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research. The findings reported in this paper are those of the author only, and should not be attributed to FaHCSIA or the Melbourne Institute. The author held no affiliation with the Productivity Commission while conducting this study. The author acknowledges the input of two anonymous referees whose comments helped to improve the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Risse, L. ‘…And one for the country’ The effect of the baby bonus on Australian women’s childbearing intentions. J Pop Research 27, 213–240 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-011-9055-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-011-9055-4