Abstract

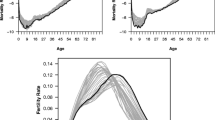

Since population censuses are not annually implemented, population estimates are needed for the intercensal period. This paper describes simultaneous implementations of the temporal interpolation and forecasting of the population census data, aggregated by age and period. Since age equals period minus cohort, age-period-cohort decomposition suffers from the identification problem. In order to overcome this problem, the Bayesian cohort (BC) model is applied. The efficacy of the BC model for temporal interpolation is examined in comparison with official Japanese population estimates. Empirical results suggest that the BC model is expected to work well in temporal interpolation. Regarding the age-period-cohort decomposition of the Japanese census data, it is shown that the cohort effect is the largest while the other two effects are very small but not negligible. With regard to the forecasting of the Japanese population, the official population forecast considerably outperforms the BC forecast in most forecast horizons. However, the pace of increase in root mean square error for longer-term forecasting is larger in the official population forecast than in the BC forecasts. As a result, a variant of the BC forecast is best for 10-year forecast.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Akaike, H. (1980). Likelihood and the Bayes procedure. In J. M. Bernardo, M. H. DeGroot, D. V. Lindley, & A. F. M. Smith (Eds.), Bayesian statistics (pp. 143–166). Valencia: Valencia University Press.

Attanasio, O. P. (1998). Cohort analysis of saving behavior by U.S. households. Journal of Human Resources, 33, 575–609.

Bijak, J., & Kupiszewska, D. (2008). Methodology for the estimation of annual population stocks by citizenship group, age and sex in the EU and EFTA Countries. Informatica, 32, 133–145.

Deaton, A., & Paxson, C. (1994). Saving, growth, and aging in Taiwan. In D. A. Wise (Ed.), Studies in the economics of aging (pp. 331–357). Chicago: Chicago University Press for NBER.

Difonzo, T. (1990). The estimation of M disaggregate time series when contemporaneous and temporal aggregates are known. Review of Economics and Statistics, 72, 178–182.

Fienberg, S. E., & Mason, W. M. (1978). Identification and estimation of age-period-cohort models in the analysis of discrete archival data. Sociological Methodology, 8, 1–67.

Fienberg, S. E., & Mason, W. M. (1985). Specification and implementation of age, period, and cohort models, In W. M. Mason & S. E. Fienberg (Eds.), Cohort analysis in social research (pp. 45–88). New York: Springer.

Fukuda, K. (2006). Age-period-cohort decomposition of aggregate data: an application to U.S. and Japanese household saving rates. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 21, 981–998.

Fukuda, K. (2007). An empirical analysis of U.S. and Japanese health insurance using age-period-cohort decomposition. Health Economics, 16, 475–489.

Fukuda, K. (2008). Age-period-cohort decomposition of U.S. and Japanese birth rates. Population Research and Policy Review, 27, 385–402.

Fukuda, K. (2009). Related-variables selection in temporal disaggregation. Journal of Forecasting, 28, 343–357.

Harvey, A. C., & Pierse, R. G. (1984). Estimating missing observations in economic time series. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 79, 125–131.

Jappelli, T. (1999). The age-wealth profile and the life-cycle hypothesis: A cohort analysis with a time series of cross-sections of Italian households. Review of Income and Wealth, 45, 57–75.

Kalwij, A. S., & Alessie, R. (2007). Permanent and transitory wages of British men, 1975–2001: Year, age and cohort effects. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 22, 1063–1093.

Kaneko, R., Ishikawa, A., Ishii, F., Sasai, T., Iwasawa, M., Mita, F., et al. (2008). Population projections for Japan: 2006–2055. Japanese Journal of Population, 6, 76–114.

Lisman, J. H. C., & Sandee, J. (1964). Derivation of quarterly figures from annual data. Applied Statistics, 13, 87–90.

Mason, K. O., Winsborough, H. H., Mason, W. M., & Poole, W. K. (1973). Some methodological issues in cohort analysis of archival data. American Sociological Review, 38, 242–258.

Mori, H., Clason, D. L., & Lillywhite, J. M. (2006). Estimating price and income elasticities in the presence of age-cohort effects. Agribusiness, 22, 201–217.

Nakamura, T. (1982). A Bayesian cohort model for standard cohort table analysis. Proceedings of the Institute of Statistical Mathematics, 29, 77–97. (In Japanese).

Nakamura, T. (1986). Bayesian cohort models for general cohort table analyses. Annals of the Institute of Statistical Mathematics, 38B, 353–370.

Ogata, Y., Katsura, K., Keiding, N., Holst, C., & Green, A. (2000). Empirical Bayes age-period-cohort analysis of retrospective incidence data. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 27, 415–432.

Rossi, N. (1982). A note on the estimation of disaggregate time series when the aggregate is known. Review of Economics and Statistics, 64, 695–696.

Zaier, L. H., & Trabelsi, A. (2007). A polynomial method for temporal disaggregation of multivariate time series. Communications in Statistics—Simulation and Computation, 36, 741–759.

Acknowledgment

I am grateful to two anonymous reviewers for very useful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Derivation of the Bayesian cohort model

Appendix: Derivation of the Bayesian cohort model

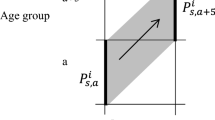

In this Appendix are further details of the derivation of the BC model. I can rewrite the model (1) with the constraints (2) in vector and matrix notation as

where \( y = (Y_{11} ,Y_{21} , \ldots ,Y_{IJ} )', \) and\( \varepsilon = (\varepsilon_{11} ,\varepsilon_{21} , \ldots ,\varepsilon_{IJ} )^{\prime}. \) X is an appropriate IJ × (I + J + K − 3) design matrix expressing the location of the effect parameters, A i , P j , and C k , as shown in Table 2. The prime (′) denotes the transpose of a vector or a matrix. The likelihood of the model (5) is given by

In order to explicitly describe the constraint (3), Nakamura assumes that the parameter vector β has the prior distribution defined by

where D is an (I + J + K − 3) × (I + J + K − 3) matrix expressing the first-order differences in the parameters, and \( \Upsigma = {\text{diag}}\left\{ {\sigma_{A}^{2} , \ldots ,\sigma_{A}^{2} ,\sigma_{P}^{2} , \ldots ,\sigma_{P}^{2} ,\sigma_{C}^{2} , \ldots ,\sigma_{C}^{2} } \right\} \). In the case of I = 3 and J = 4, D is represented as

If one specifies the values of σ 2 A , σ 2 P , and σ 2 C , it is reasonable to estimate β by the mode of the posterior density proportional to \( f\left( {y|\beta ,\sigma^{2} } \right) \cdot \pi \left( {\beta |\sigma_{A}^{2} ,\sigma_{P}^{2} ,\sigma_{C}^{2} ,\sigma^{2} } \right) \) obtained by combining Eqs. (6) and (7).

The remaining problem is how to determine the values of σ 2 A , σ 2 P and σ 2 C . As a criterion for the determination of σ 2 A , σ 2 P and σ 2 C , Nakamura adopts the ABIC which is defined by

where h is the number of hyperparameters. In the BC model, the value of ABIC is evaluated approximately by

where \( u = \left( \begin{gathered} y \hfill \\ 0 \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right),\,\,Q = \left( \begin{gathered} I\,\,\,\,X \hfill \\ 0\,\,\,\,\,D \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right),\,\,R = \left( \begin{gathered} I\,\,\,\,0 \hfill \\ 0\,\,\,\,\Upsigma \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right). \)

For further details of the derivation of the estimate \( \hat{\beta } \), its standard error, and ABIC, see Fukuda (2006).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fukuda, K. Interpolation and forecasting of population census data. J Pop Research 27, 1–13 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-010-9028-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-010-9028-z