Abstract

Background

Several studies have reported on the benefits of social support for health behaviour, including risky sex. Social support may thus be an important resource for promoting individual health and well-being, particularly in regions where HIV rates are high and healthcare resources are scarce. However, prior research on the implications of social support for the health behaviour of young women has yielded mixed and inconclusive findings. Using prospective data from young women in South Africa, this study examines the associations of social support with subsequent sexual practices, health behaviour, and health outcomes.

Method

We used two rounds of longitudinal data from a sample of n = 1446 HIV-negative emerging adult women, aged 18 to 29 years, who participated in a population-based HIV study in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Applying the analytic template for outcome-wide longitudinal designs, we estimated the associations between combinations of social support (i.e. tangible, educational, emotional) and ten HIV risk–related outcomes.

Results

Combinations of tangible, educational, and emotional support, as well as tangible support by itself, were associated with lower risk for several outcomes, whereas educational and emotional support, by themselves or together, showed little evidence of association with the outcomes.

Conclusion

This study highlights the protective role of tangible support in an environment of widespread poverty, and the additional effect of combining tangible support with non-tangible support. The findings strengthen recent evidence on the benefits of combining support in the form of cash and food with psychosocial care in mitigating risk behaviours associated with HIV and negative health outcomes among young women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Social support has emerged as a factor that can have substantial health benefits [1,2,3,4,5,6]. In contexts where social-structural disadvantages (e.g. poverty, education, inequalities) pose significant challenges to many people, psychosocial and economic supports may be important resources for promoting individual health and well-being among vulnerable populations such as young women [7,8,9,10]. Using prospective data from a sample of young women living in a high-prevalence HIV region in South Africa, this study examines associations between different combinations of social support and a range of sexual behaviour, health behaviour, and health outcomes.

There are three primary theoretical perspectives regarding how social support influences health outcomes: the stress and coping perspective, the social constructionist perspective, and the relationship perspective [10]. These perspectives differ in their explanations of how social support impacts health outcomes. According to the stress and coping perspective, social support helps individuals cope with stressful situations by enhancing their capacity to manage stress and reducing the negative impact of stress on their health. The social constructionist perspective, on the other hand, posits that social support improves an individual’s self-esteem and self-regulation, ultimately contributing to improved health outcomes. Finally, the relationship perspective suggests that social support promotes stronger social ties, which can either positively or negatively affect health outcomes depending on the norms and attitudes of the social group [10]. Thus, the relationship between social support and health is contingent on both the form of support and the type of health outcome.

Several studies have empirically documented associations between social support and behaviours related to risky sex and HIV infection. One review of empirical studies focusing on the relationship between various forms of social support and sex-related risk behaviours found that higher levels of social support are related to fewer sex-related risk behaviours among female sex workers, people living with HIV, and heterosexual adults, while noting inconsistent results for adolescents [10]. However, the evidence in Africa is limited and mixed. Out of the 40 studies reviewed, only two reported separate regression results for African women. One of those studies found that social support was correlated with consistent condom use among HIV-positive South African women [11]. In the other study, social support among Zimbabwean women was associated with fewer sexual partners, but there was no evidence of an association with condom use [12]. Two other studies included African men and women; one found that social support was unrelated to consistent condom use among HIV-positive Ugandans [13], and the other did not find evidence of an association between social support and high-risk sex (more than one partner in the past year or no condom use) among adolescents in rural Kenya [14]. In a more recent study, social support among 15–19-year-old adolescent girls living in an impoverished area of South Africa was not associated with ever having had sex or condom use, but it was associated with fewer sex partners [15].

Some studies focus on social protection, in the form of cash transfers, and sexual risk behaviours, with the findings painting a picture that is comparable to the literature on social support [16]. Although social protection is provided by governments and organizations and does not create the same social relationships as social support, it is similar to social support in the sense that it can alleviate poverty. Moreover, it sometimes includes non-tangible components, such as improved caregiver care. One study found that South African adolescent girls (aged 10–18 years) living in households with state-provided child-focused cash transfers were less likely to have had transactional and age-disparate sex than their peers, but were equally likely to have had unprotected sex, multiple partners, and sex after drinking alcohol or taking drugs [17]. The findings of studies that analyse combinations of cash transfers and other types of support, such as caregiver care and psychological support, are more promising. Cluver et al. [18] analysed the impact of integrated cash and social support from caregivers and schools to South African girls (aged 10–18 years) on HIV risk, measured by an index of a number of indicators. Both cash and social support had independent effects on HIV risk, but the combined effect was substantially stronger. Using the same data, Cluver et al. [19] showed that social support had the strongest benefits for the most vulnerable girls, as measured by structural and psychosocial factors. In a study by Stoner et al. [16], receiving a child support grant (i.e. a government cash transfer) and caregiver care were not independently associated with HIV incidence among 13–20-year-old South African females, but they were associated with reduced HIV incidence when combined.

Few attempts have been made to evaluate why social support affects risky sex and HIV infection. However, a study on South African girls found that social protection, in the form of cash transfers, and care (primarily positive parenting and good parental monitoring) were each indirectly associated with lower HIV risk behaviour by reducing psychosocial problems, whereas cash was directly associated with reduced HIV risk behaviour [19]. A qualitative study in Tanzania found that cash transfers combined with a financial education programme was successful at building agency and improving self-esteem among girls and young women aged 15–23 years, which may have allowed them to refuse unwanted sex partners [20]. Similarly, a qualitative study of Tanzanian girls and young women indicated that cash may lead to empowerment, conceptualized as “independence” and “hope and aspiration”, which appeared to give them more authority to negotiate safe sexual behaviours. This may reduce the number of sexual partners and economic reliance on transactional sex [21].

There are several potentially relevant reasons for the diverse range of findings in the prior empirical literature in this area, such as differences in conceptualization and measurement of social support, the choice of outcomes, and the characteristics of participants and the contexts in which they live [22]. However, a key limitation of most studies is the reliance on cross-sectional data, which typically are susceptible to biases. Out of the 40 studies reviewed by Qiao et al. [10], only four used longitudinal data and they were all from the USA, which differs from the African context where social-structural disadvantages are more pervasive. In addition, most prior studies have focused on a single or narrow set of outcomes, which provides an incomplete picture of how social support might be related to different outcomes of interest. By including a broader range of outcomes, one may obtain a broader and more integrative understanding of how social support may be associated with HIV-related outcomes. For example, prior research suggests that social support might not reduce sexual risk behaviour but it might reduce depression [23]. If depression is linked to risky sexual practices, we can target risky sex indirectly by addressing depression. Focusing on many outcomes in the same sample can allow one to develop a more comprehensive account of the implications of social support for health-related functioning.

To address some of the existing gaps in knowledge, this study aimed to contribute to the existing literature by assessing the associations between different types of social support and the sexual practices, health behaviour, and health outcomes of young women residing in an HIV endemic community in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. We hypothesized that tangible (cash and physical goods), educational, and emotional support in combination would generally show the strongest associations with the HIV risk–related outcomes, but we anticipated some variation in the pattern of associations by category of support and type of outcome.

Methods

Study Sample

This study is a secondary analysis of the data from the HIV Incidence Provincial Surveillance System (HIPSS) project in two sub-districts (Vulindlela and Greater Edendale) in uMgungundlovu District, KwaZulu-Natal province in South Africa [24]. uMgungundlovu is a HIV hyperendemic district with an antenatal HIV prevalence of 44% in 2016 [25]. Vulindlela is considered largely rural and Greater Edendale is largely peri urban. Men and women aged 15–49 years were enrolled from June 2014 to June 2015 (2014 Survey) and HIV seronegative participants aged 15–35 years had a single follow-up visit from June 2016 to April 2017.

All eligible participants provided written informed consent. Legal minors provided assent and written consent was obtained from parents, guardians, or caregivers. Face-to-face interviews were conducted by trained fieldworkers. The survey battery consisted of sociodemographic items, health-related measures, and HIV-related measures. Venous blood samples were collected from all participants and tested for HIV antibodies. The protocol paper provides a detailed description of the survey [24].

The analytical sample for this study consists of HIV-negative women from the 2014 Survey who were between 18 and 29 years of age (i.e. emerging adults) [26]. We limited the analysis to emerging adult females because this group is one of the more vulnerable subpopulations within the context of Eastern and Southern Africa [27]. In our baseline data, HIV prevalence in 2014 was about 3% among 18-year-olds and close to 30% among the 29-year-olds, implying an average of about 1.5% higher prevalence per 1 year increase in age. The incidence rate per 100 person-years was 4.00 for 20–24-year-olds and 2.29 for 25–29-year-olds [25].

The total sample consists of 1446 women, but the number of observations varies across the models estimated. The tables in the Electronic Supplementary Material contain information on the size of the sample used in each regression.

Measures

Social Support

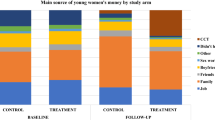

At baseline, participants indicated if they received (1) tangible support, such as money and food; (2) educational or informational support; and (3) emotional or relational support (bonding) from family, friends, work or organizations in the past month (Table 1 in Electronic Supplementary Material reports the frequencies). We used responses to these three forms of social support to create eight categories reflecting mutually exclusive combinations of social support: (1) no social support; (2) tangible support; (3) educational support; (4) emotional support; (5) educational + emotional support; (6) tangible + educational support; (7) tangible + emotional support; and (8) tangible + educational + emotional support.

Outcomes

Ten outcomes measured at baseline and follow-up were analysed, divided into sexual practices and risk behaviour (more than one sex partner, consistent condom use, sex after alcohol use, sex after drug use); health behaviour (alcohol use, drug use, HIV tested); and health (depression, HIV positive, self-reported sexually transmitted infection).

Depression was measured with the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D10) [28]. The CES-D10 is a screening instrument that evaluates the degree of depressive symptoms experienced in the past week (e.g. “I felt depressed”). Two of the items are reverse scored, with total scores ranging from 0 to 30. The factorial and cross-cultural validity of the CES-D10 has been supported in a variety of subpopulations and languages [29,30,31], including those of South Africa [32]. Previous studies have typically used cut-off points on the CES-D10 at 8, 10, or 12 to identify individuals at risk for depression [31,32,33]. Our primary analysis uses a cut-off score of 8 to classify participants into low (< 8) and high (≥ 8) risk for depression groups, which corresponds with a cut-off score of 16 on the 20-item index [34]. In the present study, estimated internal consistency of the CES-D10 at baseline was α = 0.86.

HIV infection was measured with venous blood samples collected from all participants and tested for HIV antibodies with the Biomérieux Vironostika Uniform II Antigen/Antibody Microelisa system (BioMérieux, Marcy I’Etoile, France) and HIV 1/2 Combi Roche Elecsys (Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Germany). Positive tests were confirmed with a HIV-1 Western-blot assay (Biorad assay, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Redmond, WA 98052, USA).

At baseline, STIs (excluding HIV) were also measured with blood and self-collected genital samples, testing for Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Trichomonas vaginalis and Mycoplasma genitalium, syphilis, and genital herpes (HSV-2). In the follow-up survey, only self-reported information about STIs during the last 12 months was assessed. Results for STI are based on blood and self-collected genital samples at baseline and self-reported STI in the follow-up survey. However, we also estimated models using baseline values of self-reported STI, as well as of STI based on blood and self-collected genital samples without HSV-2, as one cannot recover from HSV-2, but the differences between those results were negligible.

All other outcomes are self-reported and dichotomous (0 = No; 1 = Yes). Survey items on number of sex partners’ consistent condom use, had taken a HIV test (excluding the one taken at the 2014 Survey), used alcohol, and had sex after alcohol use refer to the past 12 months, whereas questions about drug use (dagga, heroin, cocaine, glue, tik, wunga, etc.) and sex after drug use refer to the past 6 months. The variable “number of sex partners” assesses whether participants had more than one sexual partner in the past 12 months, so all outcomes are dichotomous with 0 = No and 1 = Yes.

Covariates

To control for heterogeneity in the sample, all models were adjusted for age dichotomized into 3-year age groups (e.g. 18–20, 21–23), educational attainment (no schooling or crèche/pre-primary, primary, incomplete secondary, completed secondary, tertiary education), household wealth (quantiles based on an index of physical assets), government grants received by household (no grant or at least one grant out of eight available grants), single (not married or in union), having reduced meals during the last 5 days (a measure of poverty), and spent more than a month away from home in the previous year.

Data Analyses

All analyses were conducted using Stata 16. In the primary analysis, we regressed each outcome assessed in the follow-up wave (2016/2017) on social support assessed at baseline (2014/2015), adjusting for covariates assessed at baseline. Except for the HIV status outcome (which did not have any variability at baseline because all participants in the analytic sample were HIV negative), each model controlled for prior values of the respective outcome variable assessed at baseline. An available-case analytic approach was used. Consistent with recent recommendations [35] and prior studies [36, 37], results tables report statistical significance both before and after Bonferroni correction. Weights, adjusted for nonresponse at baseline and follow-up, were included to account for the probability of selecting the enumeration area, the household in the enumeration area, and the individual in the household (for details, see [38]).

The “no social support” category was used as the reference group, with effect estimates indicating the associations between each of the seven social support categories and the outcomes relative to the reference group in the analysis for the adjusted odds ratios. We used E-values to evaluate the sensitivity of the estimated effects to unmeasured confounding [39].

Results

The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, both in the full analytic sample and stratified by forms of social support, are reported in Table 1. The average age of the sample was 22.3 years, over 93% of participants were not in a relationship, and a majority had completed secondary education or higher (62%). The distribution of wealth was roughly equal across the quintiles, but there are more participants in the lowest quintile (25%) than in the highest (19%). About 8% of the sample had reduced the size of their meals during the last 5 days, close to 70% lived in households that received at least one government grant, and 10% had been away from home for more than a month during the last 12 months.

Table 2 reports logistic regression model estimates for the seven combinations of social support and the ten outcomes (see Electronic Supplementary Material Tables 2 to 5 for complete results). Tangible + emotional support was associated with lower odds of more than one sex partner (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.22, p = 0.0036), sex after alcohol use (AOR = 0.37, p = 0.0009), alcohol use (AOR = 0.32, p = 0.0001), and depression (AOR = 0.43, p = 0.0047). Similarly, all three forms of support in combination were associated with lower odds of sex after alcohol use (AOR = 0.31, p = 0.0010), alcohol use (AOR = 0.30, p = 0.0004), and drug use (AOR = 0.23, p = 0.0035). All three forms of support in combination were associated with lower odds of subsequently having more than one sex partner (AOR = 0.27, p = 0.0084).

Tangible support alone and all three forms of support in combination evidenced a more modest association compared to the results above, with lower odds of more than one sex partner, sex after alcohol use, sex after drug use, and depression (AORs = 0.20 to 0.57, ps ≤ 0.0500). There was little evidence to suggest that emotional and educational social support was independently associated with any of the abovementioned outcomes (ps > 0.05).

We did not find any evidence of associations between social support and subsequent HIV infection, STI status, consistent condom use, and tested for HIV (ps > 0.05). It is likely that the findings for HIV infection, consistent condom use, and tested for HIV are due to the exclusion of women who were HIV-positive, while the finding for STI status is more likely to be due to measurement errors in the follow-up survey. Nevertheless, we re-estimated the models for the four outcomes with teenagers (i.e. 15–19-year-olds), who should be less likely to have been infected by HIV (see Table 6 in the Electronic Supplementary Material). Providing some evidence that this might be the case, we found that tangible support was associated with lower odds of HIV infection (AOR = 0.20, p = 0.0460). We did not find any other evidence of associations in this subsample, but all AORs were in the expected direction. Given the small number of observations in this subsample (n = 227–654), these analyses may not have been sufficiently powered.

The choice of cut-off for the depression variable varies somewhat across studies [40]. Thus, as a robustness check, we report estimates with cut-offs at 10 and 12 (see Table 7 in the Electronic Supplementary Material). The results for cut-offs of 10 and 12 are somewhat weaker than those obtained with a cut-off of at 8, but the AORs for tangible support are similar and significantly excluded the null (AORs = 0.53, p = 0.0237; AORs = 0.43, p = 0.0045).

Since there are few observations in some categories, we re-estimated the models with a condensed measure of support. Table 8 in the Electronic Supplementary Material reports estimates of models with three categories, no support (reference category), tangible support only or combined with educational and/or emotional support, and educational and/or emotional support. The results suggest that emotional and educational support has more limited implications for the outcomes when they are not combined with tangible support.

E-values for the sensitivity analysis corresponding with the primary analysis are reported in Table 3. E-values for the effect estimates across the types of social support ranged from 1.06 to 15.07, suggesting that some of the results were at least moderately robust to potential unmeasured confounding. Slightly lower E-values were found for the limit of the confidence interval (range: 1.00, 2.92). There were variations in strength of E-values by type of support. For example, E-values for the effect estimates associated with educational and emotional support varied from 1.28 to 3.43, whereas the range for the E-values of the effect estimates of tangible support ranged more widely from 1.30 to 9.94.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that social support has the potential to effectively reduce various risk factors related to HIV infection among emerging adult women in South Africa. A key finding is that tangible social support was associated with a lower likelihood of more than one sexual partner, sex after alcohol and drug use, use of alcohol and drugs, and depression. This pattern of findings suggests that a lack of money could play an important role in the sexual and health behaviours of young women. In contexts where poverty is high, the ability to purchase various basic necessities might reduce psychosocial problems and willingness to engage in transactional sex (i.e. a sexual relationship where receiving gifts, money, or other services is an important factor in a person’s decision to engage in sex) [41].

Several of the strongest associations were observed when tangible support and emotional and educational support were combined at baseline, demonstrating the potential benefit of combinations of support in mitigating HIV risk outcomes. This might be because tangible support strengthens the effects of emotional and educational support. We also found little evidence to suggest that educational and emotional support was independently associated with the outcomes included in this study. One possible reason for this finding is that education and emotional support might be less relevant to emerging adult women living in contexts of poverty.

The findings of the study are subject to limitations. The lack of evidence of associations between social support and certain HIV risk–related outcomes (e.g. HIV infection, STIs, consistent condom use, HIV testing) could be due the short period of time between the surveys (approximately 1 year). Although HIV and STI incidence rates are high in the study area according to most standards, the number of new infections is still small. Therefore, a longer lag between waves may be needed for more definitive evidence of associations to be observed. However, underreporting is also a likely reason for not finding an association with STI. For consistent condom use, it is possible that this outcome depends more on whether a partner can be trusted than on a plan that can be affected by support from parents or others. After all, only approximately 20% of the girls and women used condoms consistently with their last partner in the two surveys, and only 7% reported using condoms consistently in both surveys. Another potential explanation for the lack of evidence of associations between social support and HIV infection, STIs, consistent condom use, or HIV testing is the exclusion of many women at high risk of being infected with HIV, since the follow-up survey only included women who were HIV-negative at baseline. That is, women who were not using condoms consistently were at higher risk of being infected by HIV and STIs than others, and they might have been more likely to have had a (positive) HIV test. To provide some evidence for this argument, models were re-estimated for adolescent girls in the sample (i.e. 15–19-year-olds), since they are less likely to have been infected by HIV than older women, even if they engaged in risky sex. Although not definitive, some of the results indicated that tangible support might have reduced the risk of HIV infection among the adolescent girls.

Another limitation is that most of the outcomes included in the present study are negative factors, but social support may be more strongly associated with positive outcomes (e.g. better performance in school, greater happiness). Moreover, we used general measures of social support that differentiated between broad categories of support, but they do not capture the nuances of the social support that participants received (e.g. amount of support, frequency of support). Finally, given that HIPSS is limited to two waves of data and not collected with the aim of testing theories, we were unable to appropriately evaluate theoretically informed mechanisms that might explain some of our findings. Further research is needed to explore the relative contribution of different theoretical perspectives to understanding how different combinations of social support might be related to HIV risk–related outcomes among emerging adult women.

In conclusion, our findings add to recent research that has evaluated the effects of cash transfer programmes and the synergistic effects of combining them with caregiver care [16, 19]. Many existing poverty and HIV interventions focus on tangible support (e.g. cash transfers to households), possibly with some conditionality attached to the provision of such resources, or on parenting education to improve their children’s behaviour and well-being [20, 42]. Although our findings suggest that tangible support may play a key role in mitigating HIV risk–related outcomes, they also indicate that it may be prudent to combine cash transfers with psychosocial care and parenting education when designing HIV prevention programmes for emerging adult women in high HIV burdened contexts.

Data Availability

The datasets used and or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ensel WM, Lin N. The life stress paradigm and psychological distress. J Health Soc Behav. 1991:321–41.

Kuwert P, Knaevelsrud C, Pietrzak RH. Loneliness among older veterans in the United States: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(6):564–9.

Kwag KH, Martin P, Russell D, Franke W, Kohut M. The impact of perceived stress, social support, and home-based physical activity on mental health among older adults. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2011;72(2):137–54.

Pettit JW, Roberts RE, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Yaroslavsky I. Developmental relations between perceived social support and depressive symptoms through emerging adulthood: blood is thicker than water. J Fam Psychol. 2011;25(1):127.

Thoits PA. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J Health Soc Behav. 2011;52(2):145–61.

Vyavaharkar M, Moneyham L, Corwin S, Tavakoli A, Saunders R, Annang L. HIV-disclosure, social support, and depression among HIV-infected African American women living in the rural southeastern United States. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011;23(1):78–90.

Goodrum NM, Armistead LP, Tully EC, Cook SL, Skinner D. Parenting and youth sexual risk in context: the role of community factors. J Adolesc. 2017;57:1–12.

Harling G, Gumede D, Shahmanesh M, Pillay D, Bärnighausen TW, Tanser F. Sources of social support and sexual behaviour advice for young adults in rural South Africa. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(6):e000955. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000955.

Cowden RG, Tucker LA, Govender K. Conceptual pathways to HIV risk in Eastern and Southern Africa: an integrative perspective on the development of young people in contexts of social-structural vulnerability. Preventing HIV Among Young People in Southern and Eastern Africa. Routledge; 2020. p. 31–47.

Qiao S, Li X, Stanton B. Social support and HIV-related risk behaviors: a systematic review of the global literature. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(2):419–41.

Gaede B, Majeke S, Modeste RRM, Naidoo JR, Titus MJ, Uys LR. Social support and health behaviour in women living with HIV in KwaZulu-Natal. SAHARA: J Soc Asp of HIV/AIDS Res Alliance. 2006;3(1):362–8.

Wilson D, Dubley I, Msimanga S, Lavelle L. Psychosocial predictors of reported HIV-preventive behaviour change among adults in Bulawayo. Zimb Cent Afr J Med. 1991;37(7):196–202.

Wagner GJ, Holloway I, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Ryan G, Kityo C, Mugyenyi P. Factors associated with condom use among HIV clients in stable relationships with partners at varying risk for HIV in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(5):1055–65.

Puffer ES, Meade CS, Drabkin AS, Broverman SA, Ogwang-Odhiambo RA, Sikkema KJ. Individual-and family-level psychosocial correlates of HIV risk behavior among youth in rural Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(6):1264–74.

Bruederle A, Delany-Moretlwe S, Mmari K, Brahmbhatt H. Social support and its effects on adolescent sexual risk taking: a look at vulnerable populations in Baltimore and Johannesburg. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(1):56–62.

Stoner MC, Edwards JK, Westreich D, Kilburn K, Ahern J, Lippman SA, et al. Modeling cash plus other psychosocial and structural interventions to prevent HIV among adolescent girls and young women in South Africa (HPTN 068). AIDS Behav. 2021;25(2):133–43.

Cluver L, Boyes M, Orkin M, Pantelic M, Molwena T, Sherr L. Child-focused state cash transfers and adolescent risk of HIV infection in South Africa: a propensity-score-matched case-control study. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1(6):e362–70.

Cluver LD, Orkin FM, Boyes ME, Sherr L. Cash plus care: social protection cumulatively mitigates HIV-risk behaviour among adolescents in South Africa. AIDS. 2014;28:S389–97.

Cluver LD, Orkin FM, Meinck F, Boyes ME, Sherr L. Structural drivers and social protection: mechanisms of HIV risk and HIV prevention for South African adolescents. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1):20646.

Pettifor A, Wamoyi J, Balvanz P, Gichane MW, Maman S. Cash plus: exploring the mechanisms through which a cash transfer plus financial education programme in Tanzania reduced HIV risk for adolescent girls and young women. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22: e25316.

Wamoyi J, Balvanz P, Atkins K, Gichane M, Majani E, Pettifor A, et al. Conceptualization of empowerment and pathways through which cash transfers work to empower young women to reduce HIV risk: a qualitative study in Tanzania. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(11):3024–32.

Toska E, Gittings L, Hodes R, Cluver LD, Govender K, Chademana KE, et al. Resourcing resilience: social protection for HIV prevention amongst children and adolescents in Eastern and Southern Africa. Afr J AIDS Res. 2016;15(2):123–40.

Fang L, Chuang D-M, Al-Raes M. Social support, mental health needs, and HIV risk behaviors: a gender-specific, correlation study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–8.

Kharsany A, Cawood C, Khanyile D, Grobler A, Mckinnon LR, Samsunder N, et al. Strengthening HIV surveillance in the antiretroviral therapy era: rationale and design of a longitudinal study to monitor HIV prevalence and incidence in the uMgungundlovu District, KwaZulu-Natal. S Afr BMC public health. 2015;15(1):1–11.

Kharsany AB, Cawood C, Lewis L, Yende-Zuma N, Khanyile D, Puren A, et al. Trends in HIV prevention, treatment, and incidence in a hyperendemic area of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1914378-e.

Arnett JJ. Introduction: emerging adulthood theory and research. In: Arnett JJ, editor. The Oxford handbook of emerging adulthood. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015. p. 1–8.

Govender K, Masebo WG, Nyamaruze P, Cowden RG, Schunter BT, Bains A. HIV prevention in adolescents and young people in the Eastern and Southern African region: a review of key challenges impeding actions for an effective response. Open AIDS J. 2018;12:53.

Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D depression symptoms index. J Aging Health. 1993;5(2):179–93.

Björgvinsson T, Kertz SJ, Bigda-Peyton JS, McCoy KL, Aderka IM. Psychometric properties of the CES-D-10 in a psychiatric sample. Assessment. 2013;20(4):429–36.

Kilburn K, Prencipe L, Hjelm L, Peterman A, Handa S, Palermo T. Examination of performance of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Short Form 10 among African youth in poor, rural households. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):1–13.

Zhang W, O’Brien N, Forrest JI, Salters KA, Patterson TL, Montaner JS, et al. Validating a shortened depression scale (10 item CES-D) among HIV-positive people in British Columbia, Canada. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7): e40793.

Baron EC, Davies T, Lund C. Validation of the 10-item centre for epidemiological studies depression scale (CES-D-10) in Zulu, Xhosa and Afrikaans populations in South Africa. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):1–14.

Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77–84.

Shean G, Baldwin G. Sensitivity and specificity of depression questionnaires in a college-age sample. J Genet Psychol. 2008;169(3):281–92.

VanderWeele TJ, Mathur MB. Some desirable properties of the Bonferroni correction: is the Bonferroni correction really so bad? Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188(3):617–8.

Cowden RG, Seidman AJ, Duffee C, Węziak-Białowolska D, McNeely E, VanderWeele TJ. Associations of suffering with facets of health and well-being among working adults: longitudinal evidence from two samples. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):20141.

Shiba K, Cowden RG, Counted V, VanderWeele TJ, Fancourt D. Associations of home confinement during COVID-19 lockdown with subsequent health and well-being among UK adults. Curr Psychol. 2022:1–10.

Grobler A, Cawood C, Khanyile D, Puren A, Kharsany AB. Progress of UNAIDS 90–90-90 targets in a district in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, with high HIV burden, in the HIPSS study: a household-based complex multilevel community survey. The Lancet HIV. 2017;4(11):e505–13.

VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-value. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(4):268–74.

Govender K, Durevall D, Cowden RG, Beckett S, Kharsany AB, Lewis L, et al. Depression symptoms, HIV testing, linkage to ART, and viral suppression among women in a high HIV burden district in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: a cross-sectional household study. J Health Psychol. 2022;27(4):936–45.

Zungu N, Toska E, Gittings L, Hodes R. 11 Closing the gap in programming for adolescents living with HIV in Eastern and Southern Africa. Preventing HIV Among Young People in Southern and Eastern Africa. 2020:243.

Marcus R, Kruja K, Rivett J. What are the impacts of parenting programmes on adolescents? A review of evidence from lowand middle-income countries. London: Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence; 2019.

Acknowledgements

Our sincere thanks to all household members and individual study participants who through their participation have contributed immensely to the understanding of the HIV epidemic in this region. A special thanks to the study staff for the field work, laboratory, and Primary Health Care clinical staff in the district. We sincerely acknowledge all the HIPSS co-investigators from the following organizations: Epicentre, CAPRISA, HEARD, NICD, and CDC. We thank our collaborating partners: The National Department of Health, Provincial KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health, uMgungundlovu Health District, the uMgungundlovu District AIDS Council, local, municipal, and traditional. We are grateful for support from the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Gothenburg. This research has been supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) under the terms of operative agreement 3U2GGH000372-02W1, the joint South Africa–US Program for Collaborative Biomedical Research from the National Institutes of Health and the South Africa-Sweden Bilateral Scientific Research Cooperation Programme financed by the Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education, the Swedish Research Council for Health Working Life and Welfare, and the Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education, and the Swedish Research Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

The survey was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, the KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Department of Health, and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

All eligible participants provided written informed consent. Legal minors provided assent and written consent was obtained from parents, guardians, or caregivers.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Statement Regarding Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Durevall, D., Cowden, R.G., Beckett, S. et al. Associations of Social Support with Sexual Practices, Health Behaviours, and Health Outcomes Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women: Evidence From a Longitudinal Study in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int.J. Behav. Med. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-023-10199-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-023-10199-6