Abstract

Background

Individuals’ physical and mental health, as well as their chances of returning to work after their ability to work is damaged, can be addressed by medical rehabilitation.

Aim

This study investigated the developmental trends of mental and physical health among patients in medical rehabilitation and the roles of self-efficacy and physical fitness in the development of mental and physical health.

Design

A longitudinal design that included four time-point measurements across 15 months.

Setting

A medical rehabilitation center in Germany.

Population

Participants included 201 patients who were recruited from a medical rehabilitation center.

Methods

To objectively measure physical fitness (lung functioning), oxygen reabsorption at anaerobic threshold (VO2AT) was used, along with several self-report scales.

Results

We found a nonlinear change in mental health among medical rehabilitation patients. The results underscored the importance of medical rehabilitation for patients’ mental health over time. In addition, patients’ physical health was stable over time. The initial level of physical fitness (VO2AT) positively predicted their mental health and kept the trend more stable. Self-efficacy appeared to have a positive relationship with mental health after rehabilitation treatment.

Conclusions

This study revealed a nonlinear change in mental health among medical rehabilitation patients. Self-efficacy was positively related to mental health, and the initial level of physical fitness positively predicted the level of mental health after rehabilitation treatment.

Clinical Rehabilitation

More attention could be given to physical capacity and self-efficacy for improving and maintaining rehabilitants’ mental health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The modern world brings new challenges to the health of workers and employees, and sedentary work and lack of physical activity are just two risk factors affecting workers’ physical and mental health [1–3]. Facilitating employee exercise can help them remain healthy [4] or become healthy again after illness [5]. If an employee’s health is affected by illness or an accident that leads to a reduced ability to work, many countries such as Germany offer medical rehabilitation to improve health, functionality, ability to work and also social participation. Rehabilitation treatment includes physical activity, psychological counseling, and the improvement of physical fitness as integral parts. To explore the role of rehabilitation in patients’ physical and mental health, functionality, capacity for social participation, and the interrelating factors of medical rehabilitation, this study recorded the trajectories of mental and physical health during and after rehabilitation using a 15-month longitudinal design. More specifically, a combination of objective and subjective measurements was used to examine the predicted role of physical fitness in mental and physical health, and to explore the relationships between self-efficacy and mental and physical health.

Medical Rehabilitation to Improve Health

Medical rehabilitation aims at partial or complete (re-)integration into working life [6, 7]. Based on the fundamental principle of the German pension fund, the insurance of such medical rehabilitation for all insured people, described as Rehabilitation, has priority over a pension (retrieved from https://www.deutsche-rentenversicherung.de/DRV/EN/Leistungen/leistungen_node.html). In Germany, medical rehabilitation typically lasts 3 weeks and is mainly delivered within specialized rehabilitation clinics [7, 8]. It is provided only if people are not able to work or are at risk for long-term reduced social participation.

Rehabilitation includes work-based exercises [e.g., shoulder and neck exercises, 9], and it has been shown to improve mental and physical health [10–12]. Bethge [13] determined the positive role of medical rehabilitation including exercises to improve ability to work among patients with chronic back pain through an elaborate cohort study. Other studies also found positive functions of rehabilitation, not only for ability to work [14, 15], but also for patients’ well-being [16], health status [17], and living conditions [18]. However, group-level analysis (such as ANOVA) ignores individual differences, especially in the process of long-term development, and group-level analysis alone cannot determine whether all individuals follow the same trend. If individual-level analysis could be conducted, ascertaining whether individual development follows the same trajectory and identifying the key time points in the individual development trends, then, the required support could be provided at the key time point, and the intervention effect can be more efficiently maximized [9].

To explore the development of mental and physical health of participants individually, and examine whether all participants follow the same trend together, a 15-month longitudinal study with four time points was conducted. ANOVA was conducted to investigate the development of patients’ physical and mental health at the group level, while the latent growth curve model (LGCM) was used to explore the trend for participants individually.

Mental Health, Physical Health, and Returning to Work

There are two important goals that should be achieved through rehabilitation before returning to work: first, mental health [7]; second, physical health [19].

Previous cohort studies, such as Tengland [20], have shown that patients with average ability to work have better physical and mental health and a lower number of absences due to sickness. Therefore, mental health is a crucial factor for rehabilitants as poor mental health increases employees’ mental stressors and reduces their subjective ability to work [21, 22].

Physical health is another essential factor for rehabilitation patients to be able to return to work [23]. As relating to physical work capacity, physical health is highly connected with mental health and return to work after rehabilitation [24, 25] and lays the basis for mental well-being and the ability to buffer the effects of stressors [19].

Subjective measurements are widely used to assess physical health [26], while objective measurements such as physical capacity are also important to consider as they are less likely to underlie social desirability or motivational influences, which typically play a role in self-report measurements. Furthermore, it is likely that such measurements offer unique contributions to an understanding of rehabilitation processes, which may facilitate or hinder successful medical rehabilitation. Thus, the present study used a relatively novel objective measurement in psychology, namely, lung functioning or oxygen reabsorption at anaerobic threshold (VO2AT).

At present, little is known about the developmental tendencies towards mental and physical health among employees undergoing medical rehabilitation. Specifically, it is still unknown whether the patients’ mental and physical health changes over time during and after medical rehabilitation. Therefore, this study used a longitudinal design and subjective and objective indicators to directly reflect the developmental trajectories of mental and physical health in rehabilitants. For this purpose, and on the basis of the literature reviewed, the following hypotheses were derived:

Hypothesis 1

Patients’ mental health improves over time, and therefore, we expect an improvement in mental health at T2, T3, and T4 compared to T1.

Hypothesis 2

Patients’ physical health improves over time.

Physical Fitness, Physical Capacity, and VO2AT

In addition to the self-reports of ability to work and health, physical capacity, which includes cardiovascular fitness, muscular strength, muscular endurance, flexibility, and body composition [27], is important for the success of a rehabilitation [28]. As an objective measure of physical fitness, VO2AT is one index of cardiopulmonary capacity, which falls into the domain of cardiovascular fitness. VO2AT signifies the oxygen consumption of the anaerobic threshold reflecting an individual’s physical fitness in many areas [18, 23, 29, 30]. Physical fitness plays an important role in maintaining physical health by alleviating clustered cardiometabolic risk [31], total and abdominal adiposity, traditional and emerging cardiovascular disease risk factors, and others [32] and has also been found to be associated with mental health [33, 34]. This study aimed to test the role of VO2AT on the developmental tendencies of mental and physical health, using the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3

The level of initial physical fitness (T1) is a positive predictor of improvement in mental health over time.

Hypothesis 4

The level of initial physical fitness (T1) is a positive predictor of improvement of physical health over time.

The Role of Self-Efficacy and the Compensatory Carry-Over Action Model

The compensatory carry-over action model [CCAM, 35] explains that health-related behaviors and social-cognitive determinants such as self-efficacy are interconnected. That is, within this perspective, a persons’ self-efficacy and well-being develop from the experience that a person is able to be physically active [36–39] and vice versa. Self-efficacy expectation is defined as the belief by an individual that they are able to successfully perform a specific behavior [40, 41], and whether this behavior is expected to generate specific outcomes is conceptualized in response-outcome expectations. In the case of strong outcome expectations (i.e., a person is convinced that a behavior leads to a desired outcome), self-efficacy expectation is important as it includes the belief that individuals can successfully initiate and maintain their behavior to ultimately produce the outcome [42]. Research has impressively shown in different meta-analyses that self-efficacy was the main driver of different behaviors and health-related outcomes [43, 44], health-related behavior [45], and quality of life [46].

Long-Term Role of Rehabilitation Treatment

The long-term interrelation of rehabilitation treatment for the development of health behaviors has been explored in several studies [47–49]. Boesen [50] found inpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation led to long-lasting improvement in health-related quality of life for multiple sclerosis patients. Pietila-Holmner, Enthoven [51] found multimodal rehabilitation programmers in primary care were beneficial for pain, physical and emotional functioning, coping, and health-related quality of life at 1-year follow-up for patients with chronic pain.

To sum up, self-efficacy plays an important role in improving mental health and physical activity, but little is known about how the changes in health experiences are interrelated with self-efficacy and physical fitness, and at what time point self-efficacy plays a role in the development of mental/physical health. Therefore, another aim was to test whether self-efficacy has a long-term interrelation with mental and physical health of patients due to the interaction of physical fitness.

Hypothesis 5

Self-efficacy is positively associated with mental health at each time point.

Hypothesis 6

Self-efficacy is positively associated with physical health at each time point.

The Present Study

To investigate the developmental trends of mental and physical health among medical rehabilitation patients and explore the role of physical fitness and self-efficacy, this study used the LGCM with a longitudinal design. The LGCM is a suitable method for exploring the tendency and the interrelating factor of rehabilitation treatment with health-related behaviors in this study [52]. For our hypotheses, we aimed to explore individual changes over time. The advantage of an LGCM over repeated measures ANCOVA is that it provides a model fit for both the intraindividual (within-person) and interindividual (between-person) changes over time. It could also examine whether all individuals follow a similar development trend [53, 54]. Previous studies have used the LGCM to explore the long-term development of health behaviors, such as physical and psychological health [55], exercise behaviors [56], and quality of life [57].

Method

Participants

In this study, 201 participants were recruited from a medical rehabilitation center in Germany and took part in a VO2AT test. All participants were rehabilitation patients. Of the recruited participants, 200 completed the questionnaire and provided useful data. One individual was excluded due to lack of questionnaire data; therefore, 200 participants constituted the final sample. A summary of the demographic characteristics of the participants is shown in Table 1.

Procedure

All participants were fully informed about the study and completed an informed consent form before taking part in this study. All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the German Psychological Society (DGPs).

At T1, participants were recruited during rehabilitation, participated in the VO2AT test, and completed paper–pencil questionnaires as described below. The following measurement time points (T2, T3, T4) took place after rehabilitation and self-report data were collected by computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI). The interviewers were student assistants supervised by an experienced researcher. Dropouts were due to lack of interest or inability to stay in contact. The demographic variables and VO2AT were measured only at baseline (T1), while questions regarding health and self-efficacy were measured at each time point. T2 was 7 months after the beginning of rehabilitation, T3 was 12 months, and T4 was 15 months after the beginning of rehabilitation. All data were merged by the participants’ unique number to ensure participant anonymity. The overview of the data collection process is shown in Table 2.

Measures

SF-12 Health Survey (SF-12)

The SF-12 is a short version of the SF-36 that includes a mental health component summary (MCS) and a physical health component summary (PCS). It reflects at least 90% measurements of the SF-36 [58, 59]. An example item is “In general, would you say your health is:” and the responses include excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor. Considering that calculating the total score of the SF-12 is not a simple sum, retest reliability was adopted here (as shown in Table 3 with bold font). The test–retest reliability coefficients for the MCS and PCS were significant (0.31–0.55), except for the values between T1 and T2–T4 for the MCS (0.02, 0.07, and 0.09), and between T1 and T2 for the PCS (0.07). The possible reason for these non-significant coefficients might be that, between T1 and T2, the rehabilitation worked, leading to the score changes measured by the SF-12 (as shown in the ANOVA results).

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy for health was assessed using the health action process approach (HAPA) model adapted from Schwarzer [60] and was measured by one item: “I am sure that I can lead a healthy life.” A 4-point Likert scale was used, where 1 = “not true,” 2 = “hardly true,” 3 = “rather true,” and 4 = “exactly true.”

VO2AT

was measured by a medical practitioner who specialized in cardiology and reflects the fitness capacity of the participants. Participants were asked to take part in a physical stress test (spinning) under constant physical exertion. During this time, spirometric data were collected by medical personnel. The VO2AT data provided information about the oxygen reabsorption of participants in percentages form: a higher VO2AT value means that participants are able to reabsorb more oxygen. Oxygen reabsorption is influenced by smoking, sex, and physical activity level [61]. VO2AT was only measured at T1.

Statistical Analyses

Based on the functions of different statistical software, R 2.70 was used for imputation of missing values, IBM SPSS version 24.0 was used for dropout and descriptive analysis and ANCOVA analysis, and MPLUS version 7.2 was used to conduct LGCMs.

First, for the missing data, the patient and doctor’s joint decision about whether the patient can work again after rehabilitation was imputed on the basis of sex and age with the procedure of k-nearest neighbor imputation implemented in R [62]. Subsequently, all the missing data were imputed on the basis of sex, age, and the joint decision of patient and doctor with the same algorithm.Footnote 1

Second, the descriptive statistics of each variable were calculated, and the Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between each pair of variables were analyzed. To explore the effectiveness of the intervention at the group level, ANOVA was conducted to compare the mental and physical health for four time points. Moreover, to explore the individual changes in the developmental tendencies for mental and physical health over time, unconditional linear and quadratic LGCMs were built. Furthermore, conditional LGCMs with VO2AT and self-efficacy for health were built to reflect their roles in the changes in mental and physical health. Insomuch that VO2AT changed little over a long time [63] and was only measured at T1, the VO2AT was considered the time-invariant covariate for the LGCM, while self-efficacy was a time-variant variable with four measurements.

For model fit of LGCM, the χ2 distribution, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) were assessed. A RMSEA from 0.10 to 0.08 indicated a moderate model fit, and a RMSEA value lower than 0.08 indicated a good model fit; a CFI between 0.90 and 0.94 was considered an acceptable model fit, and a CFI value above 0.95 indicated an excellent model fit; an SRMR value below 0.08 was considered a good model fit [64, 65].

Results

Dropout and Descriptive Analysis

Attrition analyses revealed that, at T1, participants who dropped out at T4 did not differ from participants who were tested at T4. Thus, no differences were found in SF-12 and self-efficacy scores (all t[199] < 1.11, all ps > 0.050) as well as VO2AT. There were also no differences in sex χ2(1) = 0.01, p > 0.56 (one-tailed). However, the participants who dropped out were slightly younger than those who took part at T4 (t[199] = − 2.46, p = 0.023; Mdropout = 51.27, SD = 6.76; Mparticipated = 53.71, SD = 6.73).1

Considering the large difference in the number of male (47/200) versus female study participants, a sex difference test was conducted. Results showed that men had significantly higher levels of VO2AT (F[1, 198] = 5.40, p = 0.021) and MCS scores at T3 (F[1, 198] = 4.33, p = 0.039) than women, while there were no significant sex differences in the other variables (MCS_T1–T2, MCS_T3, PCS_T1–T4, SE_T1–T4) (ps > 0.005).

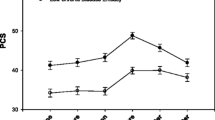

Simple descriptive statistical analysis was conducted for each variable, and the means, standard deviations, and partial correlation coefficients (with sex as the covariate) of each variable are shown in Table 3. The development tendencies of mental and physical health are depicted in Fig. 1. The results showed that VO2AT was related to mental health at T1 only, to physical health at T2–T4, and not related to self-efficacy.

Repeated Measures ANCOVA of Means on Mental and Physical Health

The original dependent variables (VO2AT, MCS_T1–T4, PCS_T1–T4, and SE_T1–T4) deviated from the normal hypothesis (all ps < 0.025), and so, the normalization process was conducted for all dependent variables. A two-step normalization approach was used to transform continuous variables to normal [66], and the transformed data was used for the following ANCOVA and LGCM analyses.

An ANCOVA with sex as a covariate was conducted. Results showed the main effect of time for mental health was significant (F[3, 196] = 5.25, p = 0.002, η2 = 0.026). Pairwise comparisons revealed the scores for mental health significantly increased from T1 to T3 (all ps < 0.011) and decreased between T3 and T4 (p < 0.001). However, mental health was at a higher level at T4 compared to T1 (p < 0.001). Furthermore, the mean scores for mental health showed a significant upward trend from T1 to T3, but a downward trend from T3 to T4 with the possibility of linear or quadratic changes. In contrast, the mean values of physical health were basically unchanged at each of the four measurements, with a non-significant main effect of time (F[3, 196] = 2.10, p = 0.105, ηpart2 = 0.01) and non-significant pairwise comparisons (all ps > 0.050).

Moreover, self-efficacy also changed over time with a non-significant effect of time (F[3, 196] = 3.05, p = 0.064, ηpart2 = 0.02), but all pairwise comparisons were significant (all ps < 0.001). The mean scores for self-efficacy significantly decreased from T1 to T2 but increased from T2 to T4. To investigate the dynamic change trend of participants’ mental and physical health over the four time points (hypotheses 1 and 2), models 1 and 2 were established below.Footnote 2

Model 1: Testing the Unconditional Linear LGCM for Mental Health Over Time

To explore whether the data was consistent with linear growth, model 1 was established. We set the loads of the slope for the first estimated linear unconditional LGCM at 0, 7, 12, and 15, based on the time points of the four measurements. As shown in Table 4, the linear model fit of the standardized result of the linear unconditional LGCM was poor [65]. The results showed that the intercept, or the initial mental health level of participants, was 47.48 (p < 0.001) and the slope was 0.55 (p < 0.001), which meant that mental health levels generally increased.

Model 2: Testing the Quadratic LGCM for Mental Health Over Time

To verify whether the data conform to the curve growth, model 2 was conducted. We again set the slope load at 0, 7, 12, and 15 in the hypothesized quadratic model (see Supplement 1) and set the quadratic load at 0, 49, 144, and 225. Model 2 fit the observed data better than model 1 (see Table 4), with a significant improvement in the model fit (Δχ2(4) = 81.45, p < 0.001).

According to the standardized results of the quadratic unconditional model, the intercept was 43.94 (p < 0.001). Mental health showed an increasing trend during the four measurement points (slope = 2.25, p < 0.001). In addition, the mean of the slope decreased over time (quadratic slope = − 0.11, p < 0.001), meaning that, during the four measurements, the mental health level increased from T1 to T3 (12 months after the beginning of rehabilitation) and then decreased from T3 to T4 (15 months after the beginning of rehabilitation).

While model 2 could describe the development tendency toward mental health, it could not reveal the reasons for the changes. To further explore the interrelating factors for mental health, we established models 3 and 4, which included the time-independent variable of VO2AT and the time-dependent variable of self-efficacy. In other words, whether changes occurred depending on other factors.

To verify whether the VO2AT and self-efficacy played a role in the trajectory of individuals’ mental health, the conditional LGCM was constructed in Models 3 and 4.

Model 3: The Quadratic Conditional LGCM of Mental Health with Time-Invariant Covariates

Considering that sex may affect the model, the quadratic conditional LGCM was first run with sex as a covariate. The result showed that the LGCM with sex was nonconvergent, which means that participants’ sex did not have a predictive role in the quadratic model. Therefore, sex was not included in the subsequent quadratic models.

To explore whether initial physical fitness could predict the initial level and growth rate of mental health, model 3 added the VO2AT as the time-invariant covariate and the remaining settings were the same as model 2.

From the standardized results of the conditional time-invariant model, the intercept meant that the level of mental health at the beginning of rehabilitation was 39.24 (p < 0.001). The slope was 3.73 (p < 0.001), and the quadratic value was − 0.19 (p < 0.001), indicating that mental health showed an increasing trend but that this increasing trend decreased between the four time points (see Supplement 2).

The interrelation of VO2AT with mental health was significant on the slope (γβ1 = − 0.096, p = 0.039) and the quadratic value (γβ2 = 0.01, p = 0.043) but was not significant on the intercept (γα = 0.30, p = 0.054). The result indicated that VO2AT played a negative role on slope, that was, the higher fitness capacity, the less the overall mental health growth. Besides, VO2AT played a positive role on the quadratic slope, meaning that individuals with higher fitness capacity had more stable mental health (larger VO2AT value contributed to larger negative quadratic value with the larger the opening of the quadratic curve, and the change of the mental health level was smaller). Moreover, VO2AT had no significant relationship with the intercept, which meant that the fitness capacity level of individuals played a subordinate role on the initial mental health level. Furthermore, oxygen reabsorption did not interrelate with the initial level of mental health.

Model 4: The Quadratic Conditional LGCM of Mental Health with Time-Invariant and Time-Variant Covariates

To test whether self-efficacy positively correlated with physical health at each time point, self-efficacy was added to model 4. Taking into consideration that self-efficacy was changing significantly over time and that this variable was measured four times, model 4 added self-efficacy as a time-variant covariate. The remaining settings were the same as model 3. The results are shown in Fig. 2, and the observed data fit the hypothesized model well, as shown in Table 4 [65].

The standardized quadratic conditional LGCM of MCS with time-invariant and time-varying covariate (model 4). T1 ~ T4 = Time1 ~ Time4; LGCM, latent growth curve model; MCS, mental health component summary; SE, self-efficacy; I, intercept; S, slope; Q, quadratic slope; CI, 95% confidence intervals. *p < .050, **p < .010, ***p < .001

From the standardized results of the conditional model, the intercept showed that the level of mental health at the beginning of the study was 37.06 (p < 0.001), the slope was 4.43 (p < 0.001), and the quadratic value was − 0.31 (p < 0.001), indicating that mental health showed an increasing trend but that this increasing trend decreased between the four time points.

The interrelation of VO2AT with mental health was significant on the intercept (γα = 0.63, p = 0.002), the slope (γβ1 = − 0.15, p = 0.002), and the quadratic value (γβ2 = 0.01, p = 0.004). These results showed that individuals with a high fitness capacity had higher initial levels of mental health, a lower healthy mental growth rate, and a stable level of mental health (lager VO2AT contributed to larger negative quadratic value with bigger opening of quadratic curve).

In addition, the level of self-efficacy for health was negatively associated with the level of mental health at T1 (T1: β = − 0.23, p = 0.010), while from T2 to T4 self-efficacy was positively related to mental health (T2: β = 0.14, p = 0.034; T3: β = 0.17, p < 0.001; T4: β = 0.16, p = 0.003), revealing the positive relationship between self-efficacy and mental health after rehabilitation treatment, and the potential effect of self-efficacy on the maintenance of mental health.

Discussion

Developmental Trajectories of Mental and Physical Health

The present study investigated the developmental trajectories of mental and physical health among medical rehabilitation patients in order to answer how mental and physical health changed over time and what roles physical fitness and self-efficacy played in these changes. The main finding of this study was that mental health underwent a nonlinear change, suggesting an increase during and after rehabilitation treatment and a decrease from the second follow-up time point (directly after rehabilitation), whereas physical health remained stable over time. Furthermore, rehabilitation and physical fitness played positive roles in the improvement of mental health, while self-efficacy did not.

Firstly, although the data did not fit the models very well, model 1 and model 2 showed that the quadratic model 2 was better than the linear model 1. Furthermore, model 3 verified hypothesis 1 with acceptable fittings of the results and revealed a U-shape development of mental health among medical rehabilitation patients. The quadratic model results indicate that rehabilitation treatment played a positive role in patients’ mental health. Mental health levels increased from the beginning of medical rehabilitation to the 12th month after the beginning of treatment. Although their mental health decreased during the 12th to the 15th month, it was still higher than it was initially. These results demonstrate the importance of medical rehabilitation and are consistent with previous studies [18, 67]. The results are also in line with Wienert, Schwarz [68], supporting the conclusion that work-related medical rehabilitation benefited the quality of life and mental health in cancer patients. Furthermore, the LGCM was used, and the results found that military veterans’ mental health demonstrated a quadratic change [69], and the workers’ psychological well-being showed linear changes [70]. It is possible that mental health is unstable and impressionable. Different measurements of time were used in this study, and in general, various interrelating factors like rehabilitation and target population might affect the shape of mental health’s developmental trajectory.

Furthermore, our ANOVA indicated that physical health status did not change, revealing that rehabilitation had little effect on patients’ physical health; therefore, further analysis was not conducted for the LGCM of physical health. These results are inconsistent with the hypotheses 2, 4, and 6, whose aims were to explore the change tendency and affecting factors for physical health. A possible reason may be that problems related to the patients’ health limited their access, frequency, and intensity of physical activity, and thus, the rehabilitation treatment may have not contributed significantly to a change in their physical health status, leading to the invariability of physical health.

Role of Physical Fitness on the Developmental Trajectory of Mental Health

Consistent with hypothesis 3, that physical fitness would play a positive role in mental health, the results of model 3 showed that VO2AT/physical fitness predicted both the initial state and development tendency of mental health, revealing that patients with higher physical fitness had higher levels of mental health. The results also showed that physical capacity (VO2AT) was associated with the physical health component at T2–T4, but not at T1. The possible reason may be that, on the one hand, VO2AT could be a good indicator of subjective health trends over time but has limited relative value at the same time point. On the other hand, when patients have just entered rehabilitation, they may be far away from home and also not able to work, which can contribute to a negative mood and thereby one’s perception of pain, health, and quality of life; thus, they may report having poor health even though an objective assessment might indicate otherwise.

Previous studies have shown physical activity and physical conditions had a positive relationship with mental health [45, 71]. Furthermore, Ho, Louie [72] found physical activity improved adolescents’ mental health, and Aparicio, Marin-Jimenez [24] noted self-reported physical function was associated with mental health in perimenopausal women. In the current study, the better the participants’ level of physical fitness, the less their mental health changed during and after the rehabilitation treatment. This result showed that patients with high physical fitness had a more stable mental health status. In particular, after the rehabilitation treatment, the mental health of the individuals slowly declined and physical fitness played a buffering role in this debility. These results implicate the potency of physical fitness on mental health, especially among medical rehabilitation patients, and indicate that improving patients’ physical fitness could not only improve mental health during medical rehabilitation, but also alleviate the decline of mental health after rehabilitation treatment and therefore maintain mental health stability.

The Interaction Between Physical Fitness and Self-Efficacy on the Developmental Trajectory of Mental Health

The fit between model 4 and the observed data was optimal, and therefore, it is consistent with hypothesis 5, which proposed that the interaction between physical fitness and self-efficacy would positively correlate with mental health after the rehabilitation treatment period. However, the results still suggest some implications: after the rehabilitation treatment, the long-term interrelations, with the rehabilitation treatment might deteriorate, and the patient’s mental health may slowly decline. In this situation, self-efficacy positively predicted the level of mental health, as higher self-efficacy led to better mental health. It is possible that, after the rehabilitation treatment, self-efficacy may have had a buffering effect on the decline of mental health. This result is consistent with previous studies [73–76] that found that self-efficacy was positively associated with mental health. One possible explanation is that self-efficacy always positively correlates with mental health, which is also described in the CCAM [35] and HAPA model [60, 77]. The potentially important positive role of self-efficacy on mental health was not shown at T1 and T2. This may be because patients were reminded of what they had learned and received support from the practitioners during the rehabilitation treatment, which masked the positive relationship between self-efficacy and mental health. However, after the rehabilitation treatment (T2-T4), patients would have to rely on their sense of self-efficacy; thus, the long-term association with rehabilitation treatment may wear off, and the true lasting effect of self-efficacy is reflected.

This result suggests that self-efficacy positively correlates with mental health after the rehabilitation treatment. More attention could be paid to patients with low self-efficacy because their mental health may decline faster than those with a higher level of self-efficacy after the rehabilitation treatment. Additionally, the improvement of their self-efficacy could also be considered a buffer for the mental health decline during the waning period of the rehabilitation treatment’s long-term interrelation.

Theoretical and Practical Contributions

The finding that mental health is subject to quadratic growth, and that physical fitness and self-efficacy are associated with these changes have theoretical and practical implications. The present results broaden the theoretical understanding of the HAPA and CCAM models of lasting developmental trends in mental health in terms of the uniform pattern of mental and physical health with an increase and then a decrease and also show that both fitness level and self-efficacy matter for mental health. Past research about HAPA or CCAM has principally focused on health behavior [78–80], such as chronic illness [77], dietary behavior [81], physical activity [82], and Internet use [39]. This study extends the model into the realm of the developmental trajectory of mental health, demonstrating that orthopedic rehabilitation patients require support with building up a high fitness level and self-efficacy for reaching or maintaining good mental health. Few studies have demonstrated this link before, and future research should test this in an interventional design.

Moreover, previous studies on HAPA and CCAM used cross-sectional [23, 79] and longitudinal methods [80]. This study used four measurement points and conducted LGCM to extend the CCAM from the group level to the individual level, showing the development tendency of mental health was nonlinear (quadratic) and similar for all individuals. Specifically, with the combination of subjective and objective measurement methods, this study used the LGCM to demonstrate how to investigate the roles of physical fitness and self-efficacy at the initial level and the rate of change in mental and physical health during and after rehabilitation treatment. Having such a long-term perspective and offering critique and feedback on the developments, not only to the previous rehabilitation patients but also to clinics and funding agencies of such treatments, will open avenues for improving the effectiveness of such therapies.

Patients’ mental health decreased after the rehabilitation, which was also found in a previous study [83]. This confirms the assumption that a nonlinear developmental tendency may be a normal phenomenon for medical rehabilitation patients. A development trend like this may occur because rehabilitation patients’ may have chronic or reoccurring mental health symptoms [84, 85], which might be very salient to them. During their rehabilitation, it is therefore suggested that patients be encouraged not to focus on problematic work or life conditions, but instead strive for a health-promotion focus that contributes to their mental health [86]. For example, patients may need to be taught coping skills that can help them better manage a chronic illness, obtain support from their employer, and understand how to seek out or use one’s social support network. As such, future studies could investigate rehabilitation patients’ support network and coping skills for chronic and recurring mental and physical health issues with regard to development trends. Moreover, future research could examine the effects in more detail to identify how this could be done. The current research demonstrates the first methodological steps for doing so.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Several limitations of the study need to be noted. First, VO2AT was not measured at all time points. The data collection at T1 when VO2AT was measured occurred during the patient’s rehabilitation program. To receive meaningful data, VO2AT can only be measured in a standardized laboratory setting where the physical activity and the constraints of the participants can be monitored. Since the data collection at T2–T4 took place via CATI, it was not possible for us to measure VO2AT at these time points. Measurement would have required patients to return to the rehabilitation clinic at T2–T4, and we assumed that we would have a much greater drop-out rate. Furthermore, the measurement of VO2AT includes a 1-h spinning session with studied nurses, which is time-consuming, exhaustive for patients, and expensive. The level of physical fitness may also change over time; thus, future studies could consider measuring VO2AT at all time points. Second, self-efficacy was measured by only one item, which may lead to poor reliability; more measurements for self-efficacy, like the General Self-Efficacy Scale [87], should be considered in the future. Third, this study only used longitudinal measurements. In order to explore the role of rehabilitation treatment, a control group and an experimental design would be interesting in future studies to shed more light on specific intervention variables and how they influence related health outcomes. Fourth, it is unknown whether the findings of this study could be applied to other populations, such as workers with job burnout [88], unemployed persons [89, 90], or military personnel [69, 91]. Further research could generalize the conclusions among other populations to explore the internal mechanisms of the mental and physical changes and lay a theoretical foundation for further intervention research, such as interventions for occupational health [92]. Fifth, this study assessed the patient’s status at 7, 12, and 15 months after leaving the hospital without structured maintenance treatment, and most patients only receive long-term treatment by a primary care therapist and physician [93]. Thus, considering the concrete treatment patients receive and its effect on long-term development of patients’ mental and physical health as well as their actual ability to work and return to work would be needed. It would also be interesting to explore which combinations of therapy are most helpful for rehabilitation patients to regain full functionality. Last, only the role of self-efficacy in mental health was investigated in this study; other important social-cognitive variables, such as social support [23, 94], merit further exploration.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study revealed a quadratic growth in mental health among medical rehabilitation patients. The quadratic model results indicate that, at the individual level, the rehabilitation treatment played a positive role in each medical rehabilitation patients’ mental health and had a long-term interrelation. In addition, their physical health maintained a stable state over time. The initial level of physical fitness was positively associated with the initial level of mental health, as well as the stability of the development tendency. Self-efficacy positively correlated with the level of mental health after the rehabilitation treatment.

Based on the results of this study, some recommendations are put forth for practitioners. First, because physical fitness is beneficial to mental health in medical rehabilitation patients, more attention should be given to physical capacity in rehabilitation for the specific benefit of improving and maintaining patients’ mental health. Second, in order to help rehabilitation patients to return to work sooner, social-cognitive determinants like self-management training or the training of work-directed self-efficacy should be considered. Our findings suggest that such interventions should be flexible and time-specific because participants develop over time. Self-management training might be very appropriate in this role as it has been shown that rehabilitation patients profit from such interventions, which include developing coping strategies, increasing knowledge of one’s disease, learning and implementing self-management behaviors, and promoting physical activity [95, 96]. Additionally, because such interventions transfer knowledge and techniques to overcome physical and psychological impairments, it would be possible to design such interventions with a stepwise approach that takes the development of patients over time into account.

Notes

Information about the raw data can be obtained from the PI of the project.

To understand sensitivity to missing data, the LGCMs based on data without the imputation procedure were conducted (see Supplement 3). To normalize the data without the imputation procedure, the two-step approach was used. The results showed that Model 1 did not fit the data well because the SRMR was .16, which is higher than the recommended value of .08. Models 2 to 4 did not converge. It is possible that the amount of data without imputation was insufficient (for the data at T4, there were only 73 valid data points).

References

Loyen, A., et al. European sitting championship: prevalence and correlates of self-reported sitting time in the 28 European Union Member States. PLoS One, 2016;11(3):e0149320.

Kazi A, et al. Sedentary behaviour and health at work: an investigation of industrial sector, job role, gender and geographical differences. Ergonomics. 2019;62(1):21–30.

Grgic J, et al. Health outcomes associated with reallocations of time between sleep, sedentary behaviour, and physical activity: a systematic scoping review of isotemporal substitution studies. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15(1):69–68.

Nawrocka A, et al. The relationship between meeting of recommendations on physical activity for health and perceived work ability among white-collar workers. Eur J Sport Sci. 2018;18(3):415–22.

Tonnon SC, et al. Strategies of employees in the construction industry to increase their sustainable employability. Work. 2018;59(2):249–58.

Bethge M, et al. Effects of nationwide implementation of work-related medical rehabilitation in Germany: propensity score matched analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2019;76(12):913–9.

Gerdes, N., Zwingmann, C. Jäckel, W. The system of rehabilitation in Germany. 2006;3–19.

Schuler M, et al. Pre-post changes in main outcomes of medical rehabilitation in Germany: protocol of a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant and aggregated data. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):e023826–e023826.

Ting, J.Z.R., Chen, X. Johnston, V. Workplace-based exercise intervention improves work ability in office workers: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(15).

Hoosain M, de Klerk S, Burger M. Workplace-based rehabilitation of upper limb conditions: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2019;29(1):175–93.

Williams RM, et al. Effectiveness of workplace rehabilitation interventions in the treatment of work-related low back pain: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(8):607–24.

Sweet SN, et al. Patterns of motivation and ongoing exercise activity in cardiac rehabilitation settings: a 24-month exploration from the TEACH study. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42(1):55–63.

Bethge M, et al. Self-reported work ability predicts rehabilitation measures, disability pensions, other welfare benefits, and work participation: longitudinal findings from a sample of German employees. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28(3):495–503.

Conroy D, Hagger MS. Imagery interventions in health behavior: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2018;37(7):668–79.

Holtermann A, Mathiassen SE, Straker L. Promoting health and physical capacity during productive work: the goldilocks principle. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2019;45(1):90–7.

Dean E. Maximizing the functional performance outcomes of patients undergoing rehabilitation by maximizing their overall health and wellbeing. BIOPHILIA. 2017;2017(2):60–60.

Parker S, et al. Reality of working in a community-based, recovery-oriented mental health rehabilitation unit: a pragmatic grounded theory analysis. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2017;26(4):355–65.

Plewnia A, Bengel J, Korner M. Patient-centeredness and its impact on patient satisfaction and treatment outcomes in medical rehabilitation. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(12):2063–70.

De Cieri H, et al. Effects of work-related stressors and mindfulness on mental and physical health among Australian nurses and healthcare workers. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2019;51(5):580–9.

Tengland PA. The concept of work ability. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21(2):275–85.

Muschalla B, et al. Mental health problem or workplace problem or something else: what contributes to work perception? Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(4):502–9.

van den Berg TIJ, et al. The effects of work-related and individual factors on the Work Ability Index: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2009;66(4):211–20.

Rinn, R, et al. Cardiopulmonary capacity and psychological factors are related to return to work in orthopedic rehabilitation patients. J Health Psychol. 2020;1359105320913946.

Aparicio VA, et al. Doctor, ask your perimenopausal patient about her physical fitness; association of self-reported physical fitness with cardiometabolic and mental health in perimenopausal women: the FLAMENCO project. Menopause. 2019;26(10):1146–53.

Brown DMY, Bray SR. Effects of Mental fatigue on exercise intentions and behavior. Ann Behav Med. 2019;53(5):405–14.

Nigg, C.R, et al. Assessing physical activity through questionnaires–a consensus of best practices and future directions. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2020:101715.

Liguori G. ACSM’s health-related physical fitness assessment manual. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2018.

Salzwedel A, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing is predictive of return to work in cardiac patients after multicomponent rehabilitation. Clin Res Cardiol. 2016;105(3):257–67.

Rafatifard, M., Mahmoodabad, S.S.M. Fallahzadeh, H. The physical activity level and aerobic capacity estimation (VO2max) among the administrative staff of the Pars Special Economic Energy Zone (Assaluyeh, Iran) with different BMIs. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2019;38(3).

Pressler A, et al. Long-term effect of exercise training in patients after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: follow-up of the SPORT:TAVI randomised pilot study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2018;25(8):794–801.

Roldão da Silva, P, et al. Health-related physical fitness indicators and clustered cardiometabolic risk factors in adolescents: a longitudinal study. J. Exerc Sci Fit. 2020;18(3):162–167.

Ortega FB, et al. Physical fitness in childhood and adolescence: a powerful marker of health. Int J Obes. 2008;32(1):1–11.

Vancampfort D, et al. Relationships between physical fitness, physical activity, smoking and metabolic and mental health parameters in people with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2012;207(1–2):25–32.

Xiang M, et al. Understanding adolescents’ mental health and academic achievement: Does physical fitness matter? Sch Psychol Int. 2017;38(6):647–63.

Lippke S. Modelling and supporting complex behavior change related to obesity and diabetes prevention and management with the compensatory carry-over action model. Journal of Diabetes and Obesity. 2014;1(2):1–5.

Dutton GR, et al. Is physical activity a gateway behavior for diet? Findings from a physical activity trial. Prev Med. 2007;46(3):216–21.

Fleig L, et al. “Sticking to a healthy diet is easier for me when I exercise regularly”: cognitive transfer between physical exercise and healthy nutrition. Psychol Health. 2014;29(12):1361–72.

Fleig L, et al. Cross-behavior associations and multiple health behavior change: a longitudinal study on physical activity and fruit and vegetable intake. J Health Psychol. 2015;20(5):525–34.

Liang W, et al. A web-based lifestyle intervention program for Chinese college students: study protocol and baseline characteristics of a randomized placebo-controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1097.

Stumpf SA, Brief AP, Hartman K. Self-efficacy expectations and coping with career-related events. J Vocat Behav. 1987;31(1):91–108.

Bilgin M, Akkapulu E. Some variables predicting social self-efficacy expectation. Soc Behav Personal Int J. 2007;35(6):777–88.

Lippke, S. Self-efficacy, in Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. 2020;1–7.

Stajkovic AD, Luthans F. Self-efficacy and work-related performance: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 1998;124(2):240–61.

Shoji K, et al. Associations between job burnout and self-efficacy: a meta-analysis. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2016;29(4):367–86.

Sheeran P, et al. The impact of changing attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy on health-related intentions and behavior: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2016;35(11):1178–88.

Banik A, et al. Self-efficacy and quality of life among people with cardiovascular diseases: a meta-analysis. Rehabil Psychol. 2018;63(2):295–312.

McGettigan, M, et al. Physical activity and exercise interventions for disease-related physical and mental health during and following treatment in people with non-advanced colorectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017.

Jiang Y, et al. The effectiveness of psychological interventions on self-care, psychological and health outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;78:16–25.

Kamiya K, et al. Multidisciplinary cardiac rehabilitation and long-term prognosis in patients with heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2020;13(10):e006798–e006798.

Boesen F, et al. Can inpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation improve health-related quality of life in MS patients on the long term – The Danish MS Hospitals Rehabilitation Study. Mult Scler. 2020;26(14):1953–7.

Pietila-Holmner, E, et al. Long-term outcomes of multimodal rehabilitation in primary care for patients with chronic pain. J Rehab Med. 2020;52(2):jrm00023-jrm00023.

McArdle JJ, Epstein D. Latent growth curves within developmental structural equation models. Child Dev. 1987;58(1):110–33.

Rovine MJ, McDermott PA. Latent growth curve and repeated measures ANOVA contrasts: what the models are telling you. Multivar Behav Res. 2018;53(1):90–101.

Preacher K.J. et al. Latent growth curve modeling. Los Angeles, Calif. u.a: Sage Publ. 2008;157.

Trindade IA, Ferreira C, Pinto-Gouveia J. The longitudinal effects of emotion regulation on physical and psychological health: a latent growth analysis exploring the role of cognitive fusion in inflammatory bowel disease. Br J Health Psychol. 2018;23(1):171–85.

Lemoyne, J., Valois, P. Wittman, W. Analyzing exercise behaviors during the college years: results from latent growth curve analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0154377.

Blank MB, Hennessy M, Eisenberg MM. Increasing quality of life and reducing HIV burden: the PATH+ intervention. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(4):716–25.

Ware, J., Jr., Kosinski, M. Keller, S.D. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33.

Wilson D, Tucker G, Chittleborough C. Rethinking and rescoring the SF-12. Sozial- Und Praventivmedizi. 2002;47(3):172–7.

Schwarzer R. Modeling health behavior change: how to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Appl Psychol. 2008;57(1):1–29.

Herdy AH, Uhlendorf D. Reference values for cardiopulmonary exercise testing for sedentary and active men and women. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2011;96(1):54–9.

Li Y, et al. Prevention through job design: identifying high-risk job characteristics associated with workplace bullying. J Occup Health Psychol. 2019;24(2):297–306.

Batterham AM, et al. Effect of supervised aerobic exercise rehabilitation on physical fitness and quality-of-life in survivors of critical illness: an exploratory minimized controlled trial (PIX study). British journal of anaesthesia : BJA. 2014;113(1):130–7.

Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological methods & research. 1992;21(2):230–58.

Hu, L.t. Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model: A Multidisciplinary J. 1999;6(1):1–55.

Templeton GF. A two-step approach for transforming continuous variables to normal: Implications and recommendations for IS research. Commun Assoc Inf Syst. 2011;28(1):41–58.

Zwerenz, R, et al. Evaluation of a transdiagnostic psychodynamic online intervention to support return to work: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2017;12(5): e0176513.

Wienert J, Schwarz B, Bethge M. Effectiveness of work-related medical rehabilitation in cancer patients: study protocol of a cluster-randomized multicenter trial. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:544.

McDaniel JT, et al. Mental health outcomes in military veterans: a latent growth curve model. Traumatology. 2018;24(3):228–35.

Firoozabadi A, Uitdewilligen S, Zijlstra FRH. Should you switch off or stay engaged? The consequences of thinking about work on the trajectory of psychological well-being over time. J Occup Health Psychol. 2018;23(2):278–88.

Barros FC, et al. Does adherence to workplace-based exercises alter physical capacity, pain intensity and productivity? European Journal of Physiotherapy. 2018;21(2):83–90.

Ho, et al. A sports-based youth development program, teen mental health, and physical fitness: An RCT. Pediatrics. 2017;140(4).

Kim DH, et al. Family stress and youth mental health problems: self-efficacy and future orientation mediation. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2019;89(2):125–33.

Schonfeld P, et al. The effects of daily stress on positive and negative mental health: mediation through self-efficacy. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2016;16(1):1–10.

Smoktunowicz E, et al. Efficacy of an Internet-based intervention for job stress and burnout among medical professionals: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20(1):338.

Steca P, et al. Cardiovascular management self-efficacy: psychometric properties of a new scale and its usefulness in a rehabilitation context. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49(5):660–74.

Schwarzer R, Lippke S, Luszczynska A. Mechanisms of health behavior change in persons with chronic illness or disability: the health action process approach (HAPA). Rehabil Psychol. 2011;56(3):161–70.

Geller K, Lippke S, Nigg CR. Future directions of multiple behavior change research. J Behav Med. 2017;40(1):194–202.

Tan SL, et al. Understanding the positive associations of sleep, physical activity, fruit and vegetable intake as predictors of quality of life and subjective health across age groups: a theory based, cross-sectional web-based study. Front Psychol. 2018;9:977.

Zhang C, et al. A meta-analysis of the health action process approach. Health Psychol. 2019;38(7):623–37.

Teleki S, et al. The role of social support in the dietary behavior of coronary heart patients: an application of the health action process approach. Psychol Health Med. 2019;24(6):714–24.

Duan, Y.P, et al. Web-based intervention for physical activity and fruit and vegetable intake among Chinese university students: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(4):e106.

Muschalla B, Linden M. Specific job anxiety in comparison to general psychosomatic symptoms at admission, discharge and six months after psychosomatic inpatient treatment. Psychopathology. 2012;45(3):167–73.

Rao A, et al. The prevalence and impact of depression and anxiety in cardiac rehabilitation: a longitudinal cohort study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020;27(5):478–89.

Janssen DJ, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in COPD patients entering pulmonary rehabilitation. Chron Respir Dis. 2010;7(3):147–57.

Lindgren, I, et al. Work conditions, support, and changing personal priorities are perceived important for return to work and for stay at work after stroke - a qualitative study. Disability and rehabilitation ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). 2020;1–7.

Luszczynska A, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. The general self-efficacy scale: multicultural validation studies. J Psychol. 2005;139(5):439–57.

Dreison KC, et al. Job burnout in mental health providers: a meta-analysis of 35 years of intervention research. J Occup Health Psychol. 2018;23(1):18–30.

Griep Y, et al. Voluntary work and the relationship with unemployment, health, and well-being: a two-year follow-up study contrasting a materialistic and psychosocial pathway perspective. J Occup Health Psychol. 2015;20(2):190–204.

Zechmann A, Paul KI. Why do individuals suffer during unemployment? Analyzing the role of deprived psychological needs in a six-wave longitudinal study. J Occup Health Psychol. 2019;24(6):641–61.

Lee JE, Sudom KA, Zamorski MA. Longitudinal analysis of psychological resilience and mental health in Canadian military personnel returning from overseas deployment. J Occup Health Psychol. 2013;18(3):327–37.

Beehr TA. Interventions in occupational health psychology. J Occup Health Psychol. 2019;24(1):1–3.

Linden M, et al. Treatment changes in general practice patients with chronic mental disorders following a psychiatric–psychosomatic consultation. Health services research and managerial epidemiology. 2018;5:2333392818758523–2333392818758523.

Teleki, S, et al. Role of received social support in the physical activity of coronary heart patients: the health action process approach. Appl Psychol : Health and Well-being. 2021.

Sindlinger K, et al. Illness representations, pain and physical function in patients with rheumatic disorders: between- and within-person associations. Psychol Health. 2019;34(2):200–15.

Manari D, et al. VO2Max and VO2AT: athletic performance and field role of elite soccer players. Sport Sciences for Health. 2016;12(2):221–6.

Acknowledgements

We thank Aike Hessel and Amanda Whittal for their support in data collection and Nara Skipper for proofreading a previous version of this manuscript and Editage for proofreading the current version of this manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study contained in this research was funded by the Deutsche Rentenversicherung Oldenburg-Bremen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All participants were fully informed about the study and completed an informed consent form before taking part in this study. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Research Involving Human and Animal Participants

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ju, Q., Gan, Y., Rinn, R. et al. Health Status Stability of Patients in a Medical Rehabilitation Program: What Are the Roles of Time, Physical Fitness Level, and Self-efficacy?. Int.J. Behav. Med. 29, 624–637 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-021-10046-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-021-10046-6