Abstract

Purpose

Socially disconnected individuals have worse health than those who feel socially connected. The mechanisms through which social disconnection influences physiological and psychological outcomes warrant study. The current study tested whether experimental manipulations of social exclusion, relative to inclusion, influenced subsequent cardiovascular (CV) and affective reactivity to socially evaluative stress.

Methods

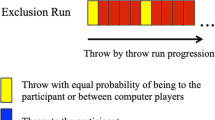

Young adults (N = 81) were assigned through block randomization to experience either social exclusion or inclusion, using a standardized computer-based task (Cyberball). Immediately after exposure to Cyberball, participants either underwent a socially evaluative stressor or an active control task, based on block randomization. Physiological activity (systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), heart rate (HR)) and state anxiety were assessed throughout the experiment.

Results

Excluded participants evidenced a significant increase in cardiovascular and affective responses to a socially evaluative stressor. Included participants who underwent the stressor evidenced similar increases in anxiety, but systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate did not change significantly in response to the stressor.

Conclusions

Results contribute to the understanding of physiological consequences of social exclusion. Further investigation is needed to test whether social inclusion can buffer CV stress reactivity, which would carry implications for how positive social factors may protect against the harmful effects of stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109(2):186–204.

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith T, Layton J. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000316.

House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science (80-). 1988;241(4865):540–5.

Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2009;50(1):31–48.

Miller G, Chen E, Cole SW. Health psychology: developing biologically plausible models linking the social world and physical health. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:501–24.

Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, Wardle J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:5797–801. 1219686110-

Uchino BN. Social support and health: A review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J Behav Med. 2006;29(4):377–87.

Uchino BN, Cacioppo JT, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The relationship between social support and physiological processes: a review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychol Bull. 1996;119(3):488–531.

Chida Y, Hamer M. Chronic psychosocial factors and acute physiological responses to laboratory-induced stress in healthy populations: a quantitative review of 30 years of investigations. Psychol Bull. 2008;134(6):829–85.

Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(3):355–91.

Inagaki TK, Eisenberger NI. Giving support to others reduces sympathetic nervous system-related responses to stress. Psychophysiology. 2016;53(4):427–35.

Kamarck TW, Manuck SB, Jennings JR. Social support reduces cardiovascular reactivity to psychological challenge: a laboratory model. Psychosom Med. 1990;52(1):42–58.

Lepore SJ, Allen KA, Evans GW. Social support lowers cardiovascular reactivity to an acute stressor. Psychosom Med. 1993;55:518–24.

Uchino BN, Garvey TS. The availability of social support reduces cardiovascular reactivity to acute psychological stress. J Behav Med. 1997;20(1):15–27.

Steptoe A, Marmot M, PhD F. Burden of psychosocial adversity and vulnerability in middle age: Associations with biobehavioral risk factors and quality of life. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(6):1029–37.

Williamson TJ, Mahmood Z, Kuhn TP, Thames AD. Differential relationships between social adversity and depressive symptoms by HIV status and racial/ethnic identity. Heal Psychol. 2017;36(2):133–42.

Wyatt SB, Williams DR, Calvin R, Henderson FC, Walker ER, Winters K. Racism and cardiovascular disease in African Americans. Am J Med Sci. 2003;325(6):315–31.

Kasl SV, Cobb S. The experience of losing a job: some effects on cardiovascular functioning. Psychother Psychosom. 1980;34(2–3):88–109.

Thorsteinsson EB, James JE. A meta-analysis of the effects of experimental manipulations of social support during laboratory stress. Psychol Health. 1999;14(5):869–86.

Bass EC, Stednitz SJ, Simonson K, Shen T, Gahtan E. Physiological stress reactivity and empathy following social exclusion: a test of the defensive emotional analgesia hypothesis. Soc Neurosci. 2014;9:1–10.

Blackhart GC, Eckel LA, Tice DM. Salivary cortisol in response to acute social rejection and acceptance by peers. Biol Psychol. 2007;75(3):267–76.

Dickerson SS, Zoccola PM. Cortisol responses to social exclusion. In: DeWall CN, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Social Exclusion. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. p. 143–51.

Sloan EK, Capitanio JP, Tarara RP, Mendoza SP, Mason WA, Cole SW. Social stress enhances sympathetic innervation of primate lymph nodes: mechanisms and implications for viral pathogenesis. J Neurosci. 2007;27(33):8857–65.

Weik U, Kuepper Y, Hennig J, Deinzer R. Effects of pre-experience of social exclusion on hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis and catecholaminergic responsiveness to public speaking stress. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60433.

Beekman JB, Stock ML, Marcus T. Need to belong, not rejection sensitivity, moderates cortisol response, self-reported stress, and negative affect following social exclusion. J Soc Psychol. 2016;156(2):131–8.

Ford MB, Collins NL. Self-esteem moderates neuroendocrine and psychological responses to interpersonal rejection. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;98(3):405–19.

McQuaid RJ, McInnis OA, Matheson K, Anisman H. Distress of ostracism: oxytocin receptor gene polymorphism confers sensitivity to social exclusion. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014;10(8):1153–9.

Stroud LR, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Wilfley DE, Salovey P. The Yale Interpersonal Stressor (YIPS): affective, physiological, and behavioral responses to a novel interpersonal rejection paradigm. Ann Behav Med. 2000;22(3):204–13.

Seidel EM, Silani G, Metzler H, Thaler H, Lamm C, Gur RC, et al. The impact of social exclusion vs. inclusion on subjective and hormonal reactions in females and males. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(12):2925–32.

Zöller C, Maroof P, Weik U, Deinzer R. No effect of social exclusion on salivary cortisol secretion in women in a randomized controlled study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(9):1294–8.

Helpman L, Penso J, Zagoory-Sharon O, Feldman R, Gilboa-Schechtman E. Endocrine and emotional response to exclusion among women and men; cortisol, salivary alpha amylase, and mood. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2017;3:253–63.

Weik U, Maroof P, Zöller C, Deinzer R. Pre-experience of social exclusion suppresses cortisol response to psychosocial stress in women but not in men. Horm Behav. 2010;58(5):891–7.

Weik U, Ruhweza J, Deinzer R. Reduced cortisol output during public speaking stress in ostracized women. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00060.

Treiber FA, Kamarck T, Schneiderman N, Sheffield D, Kapuku G, Taylor T. Cardiovascular reactivity and development of preclinical and clinical disease states. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(1):46–62.

Chida Y, Steptoe A. Greater cardiovascular responses to laboratory mental stress are associated with poor subsequent cardiovascular risk status. Hypertension. 2010;55(4):1026–32.

Earle TL, Linden W, Weinberg J. Differential effects of harassment on cardiovascular and salivary cortisol stress reactivity and recovery in women and men. J Psychosom Res. 1999;46(2):125–41.

Williams KD, Cheung CKT, Choi W. Cyberostracism: effects of being ignored over the internet. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79(5):748–62.

Hartgerink CHJ, Van Beest I, Wicherts JM, Williams KD. The ordinal effects of ostracism: a meta-analysis of 120 cyberball studies. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0127002.

Kirschbaum C, Pirke KM, Hellhammer DH. The “trier social stress test”—a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a labor atory setting. Neuropsychobioloy. 1993;28:76–81.

Deinzer R, Granrath N, Stuhl H, Twork L, Idel H, Waschul B, et al. Acute stress effects on local IL-1B responses to pathogens in a human in vivo model. Brain Behav Immun. 2004;18(5):458–67.

Eeftinck Schattenkerk DW, van Lieshout JJ, van den Meiracker AH, Wesseling KR, Blanc S, Wieling W, et al. Nexfin noninvasive continuous blood pressure validated against Riva-Rocci/Korotkoff. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22(4):378–83.

Brindle RC, Conklin SM. Daytime sleep accelerates cardiovascular recovery after psychological stress. Int J Behav Med. 2012;19(1):111–4.

Lee YSC, Suchday S, Wylie-Rosett J. Perceived social support, coping styles, and Chinese immigrants’ cardiovascular responses to stress. Int J Behav Med. 2012;19(2):174–85.

Zadro L, Williams KD, Richardson R. How low can you go? Ostracism by a computer is sufficient to lower self-reported levels of belonging, control, self-esteem, and meaningful existence. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2004;40(4):560–7.

Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto: Consult Psychol Press; 1970. p. 1–23.

Amir N, Elias J, Klumpp H, Przeworski A. Attentional bias to threat in social phobia: facilitated processing of threat or difficulty disengaging attention from threat? Behav Res Ther. 2003;41(11):1325–35.

Watson J, Nesdale D. Rejection sensitivity, social withdrawal, and loneliness in young adults. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2012;42(8):1984–2005.

Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Trevaaskis S, Nesdale D, Downey GA. Relational victimization, loneliness and depressive symptoms: indirect associations via self and peer reports of rejection sensitivity. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43(4):568–82.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self report depression scale for research in the general. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401.

Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66(1):20–40.

Liebowitz MR. Social phobia. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141–73.

Kenward MG, Roger JH. Small sample inference for fixed effects from restricted maximum likelihood. Biometrics. 1997;53:983–97.

Zwolinski J. Psychological and neuroendocrine reactivity to ostracism. Aggress Behav. 2012;38(2):108–25.

Hellhammer J, Schubert M. The physiological response to Trier Social Stress Test relates to subjective measures of stress during but not before or after the test. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(1):119–24.

Way BM, Taylor SE. A polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene moderates cardiovascular reactivity to psychosocial stress. Psychosom Med. 2011;73(4):310–7.

Roy MP, Steptoe A, Kirschbaum C. Life events and social support as moderators of individual differences in cardiovascular and cortisol reactivity. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75(5):1273–81.

Basile JN. Systolic blood pressure: it is time to focus on systolic hpyertension—especially in older people. BMJ. 2002;325(7370):917–8.

Eisenberger NI, Cole SW. Social neuroscience and health: neurophysiological mechanisms linking social ties with physical health. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(5):669–74.

Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD, Williams KD. Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science (80- ). 2003;302(5643):290–2.

Scarpa A, Luscher KA. Self-esteem, cortisol reactivity, and depressed mood mediated by perceptions of control. Biol Psychol. 2002;59(2):93–103.

Carroll D, Smith G, Shipley M, Steptoe A, Brunner E, Marmot M. Blood pressure reactions to laboratory stress and future blood pressure: a 10-year follow-up of men in the Whitehall II study. Psychosom Med. 2001;63(5):737–43.

Flaa A, Eide IK, Kjeldsen SE, Rostrup M. Sympathoadrenal stress reactivity is a predictor of future blood pressure: an 18-year follow-up study. Hypertension. 2008;52(2):336–41.

Kelly MM, Tyrka AR, Anderson GM, Price LH, Carpenter LL. Sex differences in emotional and physiological responses to the Trier Social Stress Test. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2008;39(1):87–98.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Norma Rodriguez and Anne Blackstock-Bernstein for their comments on an earlier version of this manuscript as well as to Andy Lin for providing statistical consultation. We are also thankful to Taylor Kawakami and Jennifer Burleigh for their assistance with data collection. Timothy J. Williamson acknowledges support from a National Institute of Mental Health Predoctoral Research Fellowship (MH 15750). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. There are no other financial disclosures.

Funding

This study was funded in part by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH 15750, Williamson). There are no other financial disclosures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Williamson, T.J., Thomas, K.S., Eisenberger, N.I. et al. Effects of Social Exclusion on Cardiovascular and Affective Reactivity to a Socially Evaluative Stressor. Int.J. Behav. Med. 25, 410–420 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-018-9720-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-018-9720-5