Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this review is to provide an overview of knowledge and knowledge gaps in the field of computer-based alcohol interventions by (1) collating evidence on the effectiveness of computer-based alcohol interventions in different populations and (2) exploring the impact of four specified moderators of effectiveness: therapeutic orientation, length of intervention, guidance and trial engagement.

Methods

A review of systematic reviews of randomized trials reporting on effectiveness of computer-based alcohol interventions published between 2005 and 2015.

Results

Fourteen reviews met the inclusion criteria. Across the included reviews, it was generally reported that computer-based alcohol interventions were effective in reducing alcohol consumption, with mostly small effect sizes. There were indications that longer, multisession interventions are more effective than shorter or single session interventions. Evidence on the association between therapeutic orientation of an intervention, guidance or trial engagement and reductions in alcohol consumption is limited, as the number of reviews addressing these themes is low. None of the included reviews addressed the association between therapeutic orientation, length of intervention or guidance and trial engagement.

Conclusions

This review of systematic reviews highlights the mostly positive evidence supporting computer-based alcohol interventions as well as reveals a number of knowledge gaps that could guide future research in this field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The low help-seeking rate for alcohol problems is well known, with studies pointing to around 10–15 % of people with a diagnosable alcohol problem receiving some form of treatment within the health care system [1, 2]. Although there may be several reasons for this, past research has indicated the social stigma associated with having alcohol problems a leading explanation for this discrepancy [3, 4]. For over a decade, there has been a great interest in the potential of computer-based interventions in reaching people with alcohol problems. It has been proposed that these interventions may be particularly attractive for those with alcohol problems who never seek help, due to the anonymity and 24/7 accessibility that they provide. They can also be cost-effective compared to face-to-face treatment, since no additional costs are needed once the interventions are fully developed (at least if they are fully automated), and implementation of these interventions may create wider accessibility to evidence-based interventions [5, 6].

In 2005, Kypri et al. published a paper addressing the promise and potential of computer-based interventions for alcohol problems [7]. This review concluded that the interventions seemed to have strong acceptability among patients and the public, with only a handful of effectiveness studies on computer-based alcohol interventions conducted at that time. The first systematic review focussing on treatment outcomes was published in 2008 and found the evidence with regard to effectiveness inconclusive [8]. Since then, the evidence base has expanded, with studies conducted in different countries, different contexts and different populations. In light of the emerging evidence base, several systematic reviews have attempted to combine and quantify outcomes of computer-based alcohol interventions. However, the evidence base regarding effectiveness in specific problem drinking populations (e.g. students, adults, etc.) is not yet clear.

There are also knowledge gaps in terms of identifying moderators of effectiveness. Some research has found that more extensive use of theory is associated with increased effectiveness of Internet interventions on health behaviour change [9]. Potentially linked to therapeutic orientation is intervention length, which led to a greater reduction in alcohol consumption in a systematic review of brief alcohol interventions in primary care [10]. Attention has also been given to guided Internet interventions over recent years, as these have been found to be more effective at reducing symptoms of depression than non-guided interventions in an adjoining research field [11]. Furthermore, an important methodological challenge of Internet interventions and trials in general is the impact of trial (dis-)engagement and drop-out on outcomes [12]. An overview of the extent to which these moderators of outcome have been explored in the field of computer-based alcohol interventions for problematic alcohol use is currently missing in the literature.

The aim of this paper is to summarize the evidence on computer-based alcohol interventions published over the last 10 years by narratively synthesizing the findings from systematic reviews. We will address two questions: (1) are computer-based alcohol interventions effective? and (2) what impact do therapeutic orientation, length of intervention, guidance and trial engagement have on effectiveness:?

Methods

Search Strategy

PubMed was searched on December 9, 2015 using the following terms for English language reviews published in the last 10 years: (alcohol OR drink*) AND (internet OR web-* OR online OR ehealth OR mhealth OR digital* OR computer*). We also filtered by study design: systematic reviews, meta-analysis review and scientific integrity review.

Selection Criteria

Systematic reviews were included if they (1) investigated the effectiveness of computer-based or Internet-based interventions to reduce alcohol use; (2) included studies that compared the intervention to a control group; (3) included alcohol consumption or alcohol-related harm as the principal outcome and (4) included randomized trials only or mostly. Reviews that included a combination of intervention modalities, such as in-person, telephone and Internet-based interventions were excluded. Reviews of multi-dimensional interventions including alcohol (i.e. interventions on co-occurring depression and alcohol misuse) were excluded. Reviews that focussed on computer-based interventions for a range of health behaviours were included only if findings from the studies on alcohol interventions were synthesized separately. We used the following as minimum quality criteria for inclusion in our review: (1) reported inclusion/exclusion criteria, (2) conducted adequate searches and (3) synthesized the data. These criteria are used to select systematic reviews included on the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) [13]. In addition, all systematic reviews needed to either assess the quality of included studies or provide detailed information about the included studies.

Review Screening and Data Extraction

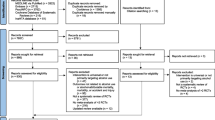

The search strategy identified 644 references. All three authors screened titles and abstracts independently. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. After discrepancies were resolved regarding which studies to exclude, full texts were acquired from the remaining 41 studies. All authors screened the full text of these papers, and consensus was reached about 14 papers to be included. One author (C.S.) extracted data from the included studies into a template for Table 1. Data extraction was checked for accuracy (M.B. and Z.K.).

Results

Fourteen systematic reviews met the eligibility criteria (see Fig. 1). Of these, one was conducted in 2008 [8], one in 2009 [14], four in 2010 [15–18], one in 2011 [19], three in 2014 [20–22] and four in 2015 [23–26] (see Table 1). Of the included reviews, ten synthesized findings statistically with meta-analyses [14–21, 24, 26].

Question 1: Are Computer-Based Interventions for Problematic Alcohol Use Effective?

In this section, we consider the evidence for the effectiveness of computer-based interventions and maintenance of these effects over time. We present evidence separately for reviews on mixed populations (reviews that include both adult and student populations), reviews on student populations only and reviews on adult (non-student) populations only. Seven reviews included studies from mixed populations [8, 15, 17, 18, 21, 22, 24] with two of these separately pooling findings from student and non-student populations [18, 24]. Five reviews restricted inclusion to studies conducted in student populations [14, 16, 23, 25, 26] and two reviews restricted inclusion to studies conducted in adult (non-student) populations [19, 20]. The most commonly reported outcome in the reviews was alcohol consumed within a given time frame (usually the preceding week) reported as number of standard drinking units or grammes of ethanol; some reviews also reported effects on binge drinking and alcohol-related problems.

Reviews on Mixed Populations

Two reviews reported outcomes in standard drinking units [15, 17]; Rooke et al. 2010 reported an effect size of 0.26 representing a small effect size [15] and White et al. 2010 reported an effect size of 0.42 representing a medium effect size [17]. Two reviews reported outcomes in grammes of ethanol per week [18, 21]; Khadjesari et al. 2010 found a statistically significant reduction in the intervention group of 26 g per week (95 % CI −41 to −11), an amount reflecting about three standard drinking units (8 g of ethanol) in the UK or 2.5 glasses in European standard drinking units (10 g of ethanol) [18]. Donoghue et al. 2014, the only review to compare different follow up times in relation to outcomes, concluded that effects on alcohol consumption were sustained at 3 months, with a mean difference of −32.74 g of ethanol, (95 % CI −56.80 to −8.68), slightly smaller effects at 3 months to less than 6 months (mean difference –17.33 g, 95 % CI –31.82 to −2.84) and from 6 months to less than 12 months follow-up (mean difference –14.91 g, 95 % CI −25.56 to −4.26). No significant effects were maintained after 12 months (mean difference –7.46 g, 95 % CI −25.34 to 10.43) [21]. One review without meta-analyses, Balhara et al. 2014 [22], considered evidence for the effectiveness of computer-based alcohol interventions inconclusive pointing to negative findings in some RCTs.

Reviews on Student Populations Footnote 1

Three reviews reported outcomes in standard drinking units [14, 16, 26]. In Carey et al. 2009’s review, computer-based interventions were found to show small effects on alcohol use, ranging from 0.09 to 0.28 for all follow-up time-points [14], while Tait et al. 2010 found a minimal effect size in alcohol consumption reduction (d = 0.12, 95 % CI 0.10 to 0.34) [16]. Dotson et al. 2015 found a small effect size on consumption (d = 0.29, 95 % CI 0.16 to 0.42) and also reported a reduction of about three drinks [26]. Dedert et al. 2015, the only review reporting outcomes in grammes of ethanol per week among students, found a mean difference of −11.7 g of ethanol (95 % CI −19.3 to −4.1) per week at 6 months between computer-based interventions and control groups reflecting a reduction of about 1.5 UK standard units or one European standard unit. At 12 months, no significant difference between groups was found [24]. Three reviews presented effect sizes on binge drinking [14, 16, 24]. Carey et al. 2009 reported a non-significant reduction (at >5 weeks) with a minimal effect size (d = 0.10, 95 % CI 0.00 to 0.20, [14], Tait et al. 2010 reported a significant reduction with a small to medium effect size (d = −0.35, 95 % CI − 0.64 to −0.06) [16], and Dedert et al. 2015 found no effect [24]. Three reviews presented effect sizes on alcohol related problems [14, 16, 26]. Carey et al. 2009 reported a minimal effect size at <5 weeks (d = 0.16, 95 % CI 0.03 to 0.29) [14] in line with the findings of Dotson et al. 2015 (d = 0.157, 95 % CI 0.037 to 0.278) [26], while Tait et al. 2010 found a moderate effect size (d = −0.57, 95 % CI− 0.98 to −0.15 [16]. Narratively, Bhochhibhoya et al. 2015 supported these findings [23], whereas Bewick et al. 2008 [8] and Leeman et al. 2015 [25] highlighted mixed findings.

Reviews on Adult (Non-Student) Populations Footnote 2

Riper et al. conducted two reviews focusing on adult problem drinkers [19, 20]; the first of the two found a medium effect size on alcohol consumption (Hedges g = 0.44, 95 % CI 0.17 to 0.71) [19] whereas the more recently published of the two found a small significant effect size (Hedges g = 0.20, 95 % CI 0.13 to 0.27). In this later review, Riper et al. also reported a significant reduction of 2.2 “alcohol consumptions” (22 g of ethanol) per week (95 % CI 0.87 to 3.46) [20]. In the review by Dedert et al. 2015, a significant reduction of 16.7 g of ethanol was found at 6 months (95 % CI −27.6 to −5.8) with no significant difference found at 12 months [24].

Khadjesari et al. 2010 conducted a sub-group analysis of studies with student populations and found the effectiveness of computer-based interventions to be less pronounced than in the wider meta-analysis of mixed student and non-student adult populations [18].

Question 2. What Is Known about Moderators of Effectiveness and Trial Engagement?

In this section, we present evidence about moderators of effectiveness and trial engagement. Specifically, we focus on four potential moderators: (1) therapeutic orientation, (2) length of intervention, (3) guidance and 4) trial engagement. Reviews that address these associations are presented in Table 2.

Therapeutic Orientation—Outcome

Eleven of the 14 reviews (79 %) addressed the association between therapeutic orientation and outcome. Four of these addressed this theme quantitatively [14, 15, 20, 25]. Carey et al. 2009 found that computer-based interventions were more successful at reducing heavy drinking frequency at long-term (≥6 weeks) when they did not provide feedback on alcohol-related problems (β = −0.63, p < 0.01) [14]. Rooke et al. 2010 compared interventions using normative feedback and relapse prevention with those that did not. No significant association was reported (normative feedback Qbetween(1) = 0.06, p = 0.80; relapse prevention Qbetween(1) = 0.01, p = 0.98) [15]. Riper et al. 2014 [20] performed subgroup analyses focussing on the relation between therapeutic orientation and outcome. Of the 16 studies included in the review, seven applied a single-focus therapeutic strategy, mostly personalized normative feedback, while the other nine studies used combined treatment approaches based on motivational interviewing, personalized normative feedback, cognitive-behavioural therapy and/or behavioural self-control and change principles. No significant association was found. Leeman et al. 2015 compared studies of personalized normative feedback interventions with studies of multi-component interventions and did not find any differences in effect sizes [25]. Other reviews addressed this issue narratively. The review by Bewick et al. 2008 suggested research on which elements of personalized feedback are related to outcome and whether those elements are different for low and high-risk drinkers [8]. Bhochhibhoya et al. 2015 found that in many studies, a theory-driven approach to interventions development was lacking, and of the included studies in this review, only 3 out of 14 utilized a theory-based intervention [23].

Length of Intervention—Outcome

Eight reviews (57 %) addressed the association between length of intervention and outcome. Three of these addressed this theme quantitatively [15, 19, 20]. Rooke et al. 2010 found a non-significant association between number of sessions and treatment effect (r = 0.17, p = 0.34) [15]. Riper et al. 2011 [19] found a significant difference (p = 0.04) between single session interventions (g = 0.27, 95 % CI 0.11 to 0.43) and more extended Internet-based self-help interventions (g = 0.61, 95 % CI 0.33 to 0.90) in sub-group analyses. However, in a more recent review by Riper et al. 2014 [20], no significant associations were found in a meta-regression between number of sessions and effect size (b = −0.0001, 95 % CI −0.004 to 0.003). White et al. 2010 noted that the prepost differential effect size for brief personalized feedback programs (d = 0.39) was somewhat smaller than the effect size for the multisession modularized programs (d = 0.56) [17]. Some reviews addressed the theme narratively; Dedert et al. 2015 stated that variability in treatment intensity was insufficient to formally test its association with outcomes [24], while Bhochhibhoya et al. 2015 concluded that more prolonged, multi-session interventions seem to be more effective than one-time interventions [23].

Guidance—Outcome

The association between guidance and outcome was addressed in five reviews (36 %). In three of these, some form of quantitative analysis on this theme was performed [14, 15, 20]. Carey et al. 2009 found that computer-based interventions were more successful in reducing alcohol-related problems at short-term (≤5 weeks) when including human interaction vs. using the computer alone (β = −0.53, p = 0.02) [14]. Rooke et al. 2010 compared interventions with minimal therapist contact (n = 32), moderate therapist contact (n = 8) and major therapist contact (n = 2). No significant association was reported, Qbetween(2) = 3.29, p = 0.19 [15]. Riper et al. 2014 did not find an association between therapist guidance and outcome: guided (g = 0.23) and unguided (g = 0.20), p = 0.73 [20]. As suggested by both Dedert et al. 2015 [24] and Riper et al. 2014 the variability in amount of guidance, and the lack of published studies on guided interventions, may not yet be sufficient for a sound evaluation of its effect on alcohol-related outcomes.

Trial Engagement—Outcome

Three reviews mentioned the possible association between trial engagement (or its reverse, drop-out) and outcome (21 %) with one of them presenting a quantitative analysis on this theme. Leeman et al. 2015 did not find differences in effect sizes between studies with retention rates at follow-up of more than 70 % versus less than 70 % [25]. White et al. 2010 reported retention in the intervention groups of the included trials ranging from 38.9 to 100 %, with a median of 74.5 % at 6 months; retention in control groups were quite similar with a range of 33.4 to 100 % and a median of 74.9 % at 6 months [17]. Dotson et al. 2015 reported drop-out rates in the included studies, ranging from 4.2 to 21 % [26]. This review in addition contended that researchers should not only measure drop-out rates but also find a way to measure whether participants actually pay attention to the intervention content as there are indications that some participants may engage in other activities while completing Internet interventions [27] in [26]].

Moderators of Trial Engagement

None of the reviews explicitly report on the association between therapeutic orientation, length of intervention and guidance and trial engagement.

Discussion

With few exceptions, across the systematic reviews eligible for this review, computer-based alcohol interventions are reported as being more effective in reducing alcohol consumption than control groups, albeit to different degrees. Effect sizes are mostly in the small range reflecting a weekly reduction of between two and three UK units or between one and 2.5 European units. Furthermore, effects seem to decay over time and may disappear completely after more than 12 months, although few studies include such long follow-ups. Interventions on students tend to render slightly smaller effects on alcohol consumption than interventions on adults/non-students. The impact of interventions on frequency of binge drinking and harm is not clear. Regarding moderators, there is at present no clear evidence for the superiority of one therapeutic orientation over another. There is mixed evidence of an association between length of intervention and outcome; some reviews found support for the hypothesis that the longer the length or duration of an intervention, the larger its effects, but not all. There is also mixed evidence for an added effect of guidance. Lastly, there is a lack of evidence regarding impact of trial engagement on outcome, with only one review addressing this issue quantitatively.

Despite positive findings in the included reviews, a few recent large-scale pragmatic trials on computer-based interventions have reported null findings. Kypri et al. 2014 found no significant reductions in volume or frequency of alcohol consumption in a large trial conducted in seven New Zealand universities (5135 students) [28] and another recently conducted trial in a workplace setting also found no differences (1330 employees) [29]. Whilst these studies provide different reasons for their null findings, reactivity of assessment, caused by the screening test [30] and other features of the research process [31] may provide some explanation. The findings of these trials may also be a function of their pragmatic designs, where implementation in “real world” contexts may hinder the effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions [32]. Future reviews would benefit from grading the extent to which trials measure the efficacy or effectiveness of interventions [10, 33] and exploring the extent to which this impacts on their findings.

Although the reviews found no utility of therapeutic orientation as a moderator, there was some evidence that longer interventions are more effective than briefer ones. However, it may be difficult to disentangle effects of therapeutic orientation and length of intervention in the field of computer-based interventions for problematic alcohol use. These interventions mainly fall into two therapeutic traditions: brief interventions and cognitive behaviour therapy/relapse prevention. Computer-based brief interventions are usually single-module meant to be used only once, and computer-based cognitive behaviour therapy/relapse prevention interventions usually consist of several modules intended to be used repeatedly over an extended period of time. This inter-relation of therapeutic orientation and length of intervention complicates findings. To illustrate, in a study by Cunningham 2012, two Internet-based interventions were directly compared; one brief intervention with personalized feedback intended for completion in a single session but accessible for repetition should the user wish to use it again, and one cognitive behaviour therapy/relapse prevention intervention consisting of several modules specifically intended for repeated use over an extended time period [34]. Although the extended version was shown to be more effective in reducing alcohol consumption, the data does not tell us whether therapeutic orientation or intervention length (or a combination of the two) was the (more) effective component. This considered, it is important that future analyses on computer-based interventions find ways to disentangle the relationship between these two moderators.

The potential of the Internet in delivering effective, individual-level interventions at population level is currently being realized by health agencies across Europe. The National Health Service in England offers the One You Drinks tracker app [35], the Swedish alcohol monopoly Systembolaget has developed the Promillekoll app which focuses on blood alcohol concentration [36] and the intervention database on the Dutch portal for Health Promotion and Prevention supported by the Netherlands Ministry of Health, currently lists 14 alcohol Internet interventions [37]. Whilst this is a promising development, it is important that interventions intended to be widely disseminated under-go robust evaluation and that effective implementation strategies, best suited to their context, are used [38]. Furthermore, if these interventions are intended to create a public health impact, it is vital to extend the reach of them to the whole target population. Accordingly, a relevant theme for future research would be to find effective ways to get the target population to find and access the intervention. A recent review on the possibilities of using online methods to recruit participants of Internet-based trials for a variety of health domains indicates that although online recruitment is promising for this, more empirical evidence is needed [39].

Strengths and Limitations

A significant strength of this review is that it followed a robust methodology and answered two specific questions determined a priori, with findings synthesized narratively in response to these questions. However, some limitations should be mentioned: Whilst we had minimum quality criteria for the inclusion of systematic reviews in our review, we did not undertake a quality assessment of the reviews. For reviews published until the end of 2014, however, critical summaries are available from the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) [13]. Furthermore, discussion of moderators was not based on experimental data but was limited to meta-regression (i.e. observational data) in the included reviews. There is a growing literature that uses experimental design to explore the impact of some of these moderators [34, 40–42]. Finally, some individual RCT’s are included in several reviews; the results of the reviews are thus not fully independent of each other.

Recommendations for Future Research

A number of themes worth considering in future research have been identified in our review of systematic reviews on computer-based alcohol interventions, which has led us to four recommendations.

Firstly, there is a clear lack of studies with long-term follow-ups. Most primary studies and (hence) reviews have follow-up durations of 6 months post-randomisation or shorter. More outcome data of 12 months post-randomisation (or longer) would allow a knowledge base with regard to long-term effects to be established. Positive findings would support the acceptance of these interventions as valuable high quality treatment. Negative findings (no or very limited maintenance of effects at 12 months post-randomisation) could guide improvements to interventions, with for example a focus on possible merits of booster sessions.

Secondly, although two out of three reviews that analysed guidance quantitatively found no effect of this moderator, there are several individual studies that have reported a clear and significant added effect of guidance [42, 43]. Given that guidance has been shown to improve effects in studies on Internet interventions in other problem areas [44], more research on the impact of (different levels of) guidance in computer-based alcohol interventions is needed to clarify what amount, if any, leads to optimal effect. Cost-effectiveness would also be an important consideration here, as therapist involvement constitutes a major cost driver [45].

Thirdly, even though there is a steady evidence base for computer-based alcohol interventions in adult and student populations, there is lack of evidence in other populations such as patients, employees and ethnic minority groups. Future primary studies and reviews should limit inclusion to these or other populations, in order to demonstrate utility of interventions in these specific groups.

A fourth and final recommendation concerns trial engagement: many reviews (and primary papers) mention the potential negative impact of trial drop-out on the quality and validity of the available literature. However, as of yet, none of the outcome-oriented reviews performs meta-regression on moderators of trial drop-out, nor on approaches to foster engagement. Addressing these issues quantitatively would be a valuable contribution to current evidence and could inform intervention developers and researchers on potential mechanisms to foster engagement, the impact of addressing these mechanisms, and means to reduce intervention and trial drop-out.

Notes

Even though Bewick et al. 2008 and Tait et al. 2010 did not restrict inclusion to a student population, they both are included in this section since 4 out of 5 studies and 13 out of 14 studies respectively were conducted in student setting.

All reviews mentioned in this subsection include a small number of studies in non-health-care settings such as the workplace and the military, and trials in health care settings, such as General Practice, emergency departments, and women and infant services. These findings tend to be pooled with all non-student studies, due to their small numbers.

References

Cohen E, Feinn R, Arias A, Kranzler HR. Alcohol treatment utilization: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86(2–3):214–21. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.06.008.

Rehm J, Shield K, Rehm M, Gmel G, Frick U. Alcohol consumption, alcohol dependence and attributable burden of disease in Europe. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. 2012.

Cunningham JA, Breslin FC. Only one in three people with alcohol abuse or dependence ever seek treatment. Addict Behav. 2004;29(1):221–3 Epub 2003/12/12. PubMed.

Grant BF. Barriers to alcoholism treatment: reasons for not seeking treatment in a general population sample. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58(4):365–71 Epub 1997/07/01. PubMed.

Cunningham JA, Kypri K, McCambridge J. The use of emerging technologies in alcohol treatment. Alcohol research & health : the journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. 2011;33(4):320–6 Epub 2011/01/01. PubMed PMID: 23580017; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc3860543.

Griffiths F, Lindenmeyer A, Powell J, Lowe P, Thorogood M. Why are health care interventions delivered over the internet? A systematic review of the published literature. Journal of medical Internet research. 2006;8(2):e10 .Epub 2006/07/27. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8.2.e10. PubMed PMID: 16867965; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc1550698

Kypri K, Sitharthan T, Cunningham JA, Kavanagh DJ, Dean JI. Innovative approaches to intervention for problem drinking. Current opinion in psychiatry. 2005;18(3):229–34. doi:10.1097/01.yco.0000165591.75681.ab.

Bewick BM, Trusler K, Barkham M, Hill AJ, Cahill J, Mulhern B. The effectiveness of web-based interventions designed to decrease alcohol consumption—a systematic review. Prev Med. 2008;47(1):17–26. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.01.005.

Webb TL, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie S. Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. Journal of medical Internet research. 2010;12(1):e4. doi:10.2196/jmir.1376.

Kaner EF, Beyer F, Dickinson HO, Pienaar E, Campbell F, Schlesinger C, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2007;(2):Cd004148. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub3.

Richards D, Richardson T. Computer-based psychological treatments for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32(4):329–42. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.02.004.

Murray E, White IR, Varagunam M, Godfrey C, Khadjesari Z, McCambridge J. Attrition revisited: adherence and retention in a web-based alcohol trial. Journal of medical Internet research. 2013;15(8):e162. doi:10.2196/jmir.2336.

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) Available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/CRDWeb/AboutPage.asp.

Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LA, Elliott JC, Bolles JR, Carey MP. Computer-delivered interventions to reduce college student drinking: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2009;104(11):1807–19. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02691.x.

Rooke S, Thorsteinsson E, Karpin A, Copeland J, Allsop D. Computer-delivered interventions for alcohol and tobacco use: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2010;105(8):1381–90. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02975.x.

Tait RJ, Christensen H. Internet-based interventions for young people with problematic substance use: a systematic review. Med J Aust. 2010;192(11 Suppl):S15–21.

White A, Kavanagh D, Stallman H, Klein B, Kay-Lambkin F, Proudfoot J, et al. Online alcohol interventions: a systematic review. Journal of medical Internet research. 2010;12(5):e62. doi:10.2196/jmir.1479.

Khadjesari Z, Murray E, Hewitt C, Hartley S, Godfrey C. Can stand-alone computer-based interventions reduce alcohol consumption? A systematic review. Addiction. 2011;106(2):267–82. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03214.x.

Riper H, Spek V, Boon B, Conijn B, Kramer J, Martin-Abello K, et al. Effectiveness of E-self-help interventions for curbing adult problem drinking: a meta-analysis. Journal of medical Internet research. 2011;13(2):e42. doi:10.2196/jmir.1691.

Riper H, Blankers M, Hadiwijaya H, Cunningham J, Clarke S, Wiers R, et al. Effectiveness of guided and unguided low-intensity internet interventions for adult alcohol misuse: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(6). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0099912.

Donoghue K, Patton R, Phillips T, Deluca P, Drummond C. The effectiveness of electronic screening and brief intervention for reducing levels of alcohol consumption: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of medical Internet research. 2014;16(6):e142. doi:10.2196/jmir.3193.

Balhara Y, Verma RA. Review of web based interventions focusing on alcohol use. Annals of medical and health sciences research. 2014;4(4). doi:10.4103/2141-9248.139272.

Bhochhibhoya A, Hayes L, Branscum P, Taylor L. The use of the internet for prevention of binge drinking among the college population: a systematic review of evidence. Alcohol Alcohol. 2015;50(5):526–35. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agv047.

Dedert EA, McDuffie JR, Stein R, McNiel JM, Kosinski AS, Freiermuth CE, et al. Electronic interventions for alcohol misuse and alcohol use disorders: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(3):205–14. doi:10.7326/m15-0285.

Leeman RF, Perez E, Nogueira C, DeMartini KS. Very-brief, web-based interventions for reducing alcohol use and related problems among college students: a review. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:129. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00129.

Dotson KB, Dunn ME, Bowers CA. Stand-alone personalized normative feedback for college student drinkers: a meta-analytic review, 2004 to 2014. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0139518. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0139518.

Lewis MA, Neighbors C. An examination of college student activities and attentiveness during a web-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Psychology of addictive behaviors: journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors. 2015;29(1):162–7. doi:10.1037/adb0000003.

Kypri K, Vater T, Bowe SJ, Saunders JB, Cunningham JA, Horton NJ, et al. Web-based alcohol screening and brief intervention for university students: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(12):1218–24. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.2138.

Khadjesari Z, Newbury-Birch D, Murray E, Shenker D, Marston L, Kaner E. Online health check for reducing alcohol intake among employees: a feasibility study in six workplaces across England. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0121174. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121174.

McCambridge J, Kypri K. Can simply answering research questions change behaviour? Systematic review and meta analyses of brief alcohol intervention trials. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e23748. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023748.

McCambridge J, Kypri K, Elbourne D. Research participation effects: a skeleton in the methodological cupboard. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(8):845–9. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.002.

Heather N. The efficacy-effectiveness distinction in trials of alcohol brief intervention. Addiction science & clinical practice. 2014;9:13. doi:10.1186/1940-0640-9-13.

Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, Donnan P, Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M. The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2015;350:h2147. doi:10.1136/bmj.h2147.

Cunningham JA. Comparison of two internet-based interventions for problem drinkers: randomized controlled trial. Journal of medical Internet research. 2012;14(4):e107. doi:10.2196/jmir.2090.

One You Drinks application. Available from: http://www.nhs.uk/Tools/Pages/drinks-tracker.aspx.

Gajecki M, AH B, Sinadinovic K, Rosendahl I, Andersson C. Mobile phone brief intervention applications for risky alcohol use among university students: a randomized controlled study. Addiction science & clinical practice. 2014;9:11. doi:10.1186/1940-0640-9-11.

Dutch portal for Health Promotion and Prevention. Available from: http://www.loketgezondleven.nl.

Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implementation science : IS. 2015;10:21. doi:10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1.

Lane TS, Armin J. Online Recruitment Methods for Web-Based and Mobile Health Studies: A Review of the Literature. 2015;17(7):e183. doi:10.2196/jmir.4359.

Tensil MD, Jonas B, Struber E. Two fully automated web-based interventions for risky alcohol use: randomized controlled trial. Journal of medical Internet research. 2013;15(6):e110. doi:10.2196/jmir.2489.

Sinadinovic K, Wennberg P, Johansson M, Berman AH. Targeting individuals with problematic alcohol use via web-based cognitive-behavioral self-help modules, personalized screening feedback or assessment only: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Addict Res. 2014;20(6):305–18. doi:10.1159/000362406.

Sundström C, Gajecki M, Johansson M, Blankers M, Sinadinovic K, Stenlund-Gens E, et al. Guided and unguided internet-based treatment for problematic alcohol use—a randomized controlled pilot trial. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0157817. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157817.

Blankers M, Koeter MW, Schippers GM. Internet therapy versus internet self-help versus no treatment for problematic alcohol use: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(3):330–41. doi:10.1037/a0023498 .PubMed

Andersson G, Cuijpers P, Carlbring P, Riper H, Hedman E. Guided internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA). 2014;13(3):288–95. doi:10.1002/wps.20151.

Blankers M, Nabitz U, Smit F, Koeter MW, Schippers GM. Economic evaluation of internet-based interventions for harmful alcohol use alongside a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Journal of medical Internet research. 2012;14(5):e134. doi:10.2196/jmir.2052.

Acknowledgments

Zarnie Khadjesari is a King’s Improvement Science postdoctoral fellow at King’s College London. King’s Improvement Science is part of the Centre for Implementation Science at the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South London.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sundström, C., Blankers, M. & Khadjesari, Z. Computer-Based Interventions for Problematic Alcohol Use: a Review of Systematic Reviews. Int.J. Behav. Med. 24, 646–658 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-016-9601-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-016-9601-8