Abstract

Background

The relationship between religiosity and health has been investigated in the western world for decades. However, very little data are available from the post-communist region of Europe, where religion was suppressed for a long time.

Purpose

The aim of the present study was to lessen this gap.

Methods

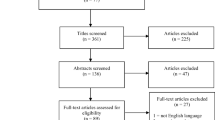

In 2002, 13 years after the regime change, 12,643 persons (mean age = 47.6 ± 17.9 years; 44.8 % male) were interviewed in a Hungarian representative survey. The relationship of mental and physical health indicators with religious worship and personal importance of religion—controlling for several psychological and lifestyle characteristics—were analyzed using the general linear model procedure.

Results

Our results showed that practicing religion was largely associated with better mental health and more favorable physical health status. However, persons being religious in their own way tended to show more unfavourable results across several variables when compared to those practicing religion regularly in a religious community or even to those considering themselves as non-religious. The personal importance of religion showed a mixed pattern, since it was positively associated not only with well-being but depression and anxiety as well.

Conclusions

We can conclude that even after an anti-religious totalitarian political system practicing religion still remained a health protecting factor.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Koenig HG. Medicine, religion and health: where science and spirituality meet. West Conshohocken: Templeton Foundation Press; 2008.

Matthews DA, McCullough ME, Larson DB, Koenig HG, Swyers JP, Greenwold MM. Religious commitment and health status. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:118–24.

Hummer RA, Rogers RG, Nam CB, Ellison CG. Religious involvement and US adult mortality. Demography. 1999;2:273–85.

Chida Y, Steptoe A, Powell LH. Religiosity/spirituality and mortality. A systematic quantitative review. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;2:81–90.

Koenig HG. Research on religion, spirituality, and mental health: a review. Can J Psychiatr. 2009;54:283–91.

Krause N. Religion and health: making sense of a disheveled literature. J Relig Health. 2011;50:20–35.

Baetz M, Griffin R, Bowen R, Koenig HG, Marcoux E. The association between spiritual and religious involvement and depressive symptoms in a Canadian population. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;12:818822.

Lee EO. Religion and spirituality as predictors of well-being among Chinese American and Korean American older adults. J Relig Spiritual Aging. 2007;19:77–100.

Green M, Elliott M. Religion, health, and psychological well-being. J Relig Health. 2010;49:149–63.

Levin J. Religion and mental health: theory and research. Int J Appl Psychoanal Stud. 2010;7:102–15.

Sephton SE, Koopman C, Schaal M, Thoresen C, Spiegel D. Spiritual expression and immune status in women with metastatic breast cancer: an exploratory study. Breast J. 2001;7:345–53.

Gillum RF, Ingram DD. Frequency of attendance at religious services, hypertension, and blood pressure: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:382–5.

Idler EL, Kasl SV. Religion among disabled and nondisabled persons II: attendance at religious services as a predictor of the course of disability. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1997;52B:S306–16.

Goldbourt U, Yaari S, Medalie JH. Factors predictive of long-term coronary heart disease mortality among 10,059 male Israeli civil servants and municipal employees. Cardiology. 1993;82:100–21.

Oman D, Kurata JH, Strawbridge WJ, Cohen RD. Religious attendance and cause of death over 31 years. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2002;32:69–89.

Jarvis GK, Northcott HC. Religion and differences in morbidity and mortality. Soc Sci Med. 1987;25:813–24.

Lee BY, Newberg AB. Religion and health: a review and critical analysis. Zygon. 2005;40:443–68.

McCullough ME, Hoyt WT, Larson DB, Koenig HG, Thoresen C. Religious involvement and mortality: a meta-analytic review. Health Psychol. 2000;19:211–22.

Strawbridge WJ, Cohen RD, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA. Frequent attendance at religious services and mortality over 28 years. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:957–61.

Schnall E, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Swencionis C, Zemon V, Tinker L, O’Sullivan MJ, et al. The relationship between religion and cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality in the women’s health initiative observational study. Psychol Health. 2010;25:249–63.

Piko BF, Fitzpatrick KM. Substance use, religiosity, and other protective factors among Hungarian adolescents. Addict Behav. 2004;29:1095–107.

Kovács E, Pikó B, Fitzpatrick KM. Religiosity as a protective factor against substance use among Hungarian high school students. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;10:1346–57.

Nicholson A, Rose R, Bobak M. Association between attendance at religious services and self-reported health in 22 European countries. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:519–28.

Skrabski Á, Kopp M, Rózsa S, Réthelyi J, Rahe R. Life meaning: an important correlate of health in the Hungarian population. Int J Behav Med. 2005;12:78–85.

Török P. Hungarian church–state relationships. A socio-historical analysis. Collected studies of the Hungarian Institute for Sociology of Religion. Budapest: Hungarian Institute for Sociology of Religion; 2003. p. 103–4.

Zrinščak S. Generations and atheism: patterns of response to communist rule among different generations and countries. Soc Compass. 2004;2:221–34.

Froese P. A supply-side interpretation of the Hungarian religious revival. J Sci Study Relig. 2001;2:251–68.

Tomka M. Coping with persecution. Int Sociol. 1998;2:229–48.

Skrabski Á, Kopp MS, Kawachi I. Social capital and collective efficacy in Hungary: cross-sectional associations with middle aged female and male mortality rates. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58:340–5.

Rózsa S, Réthelyi J, Stauder A, Susánszky É, Mészáros E, Skrabski Á, et al. A Hungarostudy 2002 országos reprezentatív felmérés általános módszertana és a felhasznált tesztbattéria pszichometriai jellemzői [General methodology of the Hungarostudy 2002 national representative survey and psychometric properties of the test battery]. Psychiatr Hung. 2003;18:83–94.

Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:21–37.

Kopp MS, Skrabski Á. Magyar lelkiállapot az ezredfordulón [Hungarian state of mind at the millennium]. Távlatok. 2000;4:499–513.

Koenig HG. The handbook of religion and health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001.

Scandrett KG, Mitchell SL. Religiousness, religious coping, and psychological well-being in nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10:581–6.

Gillum RF. Frequency of attendance at religious services and cigarette smoking in American women and men: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Prev Med. 2005;41:607–13.

Gillum RF. Frequency of attendance at religious services and leisure-time physical activity in American women and men: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31:30–5.

Piko BF, Kovacs E, Kriston P, Fitzpatrick KM. “To believe or not to believe?” religiosity, spirituality, and alcohol use among Hungarian adolescents. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73:666–74.

Bowling A. Just one question: if one question works, why ask several? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:342–5.

Bech P, Gudex C, Johansen KS. The WHO (Ten) Well-Being Index: validation in diabetes. Psychother Psychosom. 1996;65:183–90.

Susánszky É, Konkolÿ Thege B, Stauder A, Kopp M. A WHO Jól-lét Kérdőív rövidített (WBI-5) magyar változatának validálása a Hungarostudy 2002 országos lakossági egészségfelmérés alapján [Validation of the short (five-item) version of the WHO Well-Being Scale based on a Hungarian representative health survey (Hungarostudy 2002)]. J Ment Health Psychosom. 2006;7:247–55.

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1961;4:561–71.

Rózsa S, Szádóczky E, Füredi J. A Beck Depresszió Kérdőív rövidített változatának jellemzői hazai mintán [Psychometric properties of the Hungarian version of the shortened Beck Depression Inventory]. Psychiatr Hung. 2001;16:384–402.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70.

Muszbek K, Székely A, Balogh É, Molnár M, Rohánszky M, Ruzsa Á, et al. Validation of the Hungarian translation of Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:761–6.

Rahe RH, Tolles RL. The brief stress and coping inventory: a useful stress management instrument. Int J Stress Manag. 2002;9:61–70.

Konkolÿ Thege B, Martos T, Skrabski Á, Kopp M. Rövidített Stressz és Megküzdés Kérdőív élet értelmességét mérő alskálájának (BSCI-LM) pszichometriai jellemzői [Psychometric properties of the Life Meaning Subscale from the Brief Stress and Coping Inventory (BSCI-LM)]. J Ment Health Psychosom. 2008;9:243–61.

Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L. The measurement of pessimism: the Hopelessness Scale. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1974;42:861–5.

Perczel-Forintos D, Sallai J, Rózsa S. A Beck-féle Reménytelenség Skála pszichometriai vizsgálata [Psychometric evaluation of the Beck Hopelessness Scale]. Psychiatr Hung. 2001;16:632–43.

Folkman S, Lazarus RS. An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. J Health Soc Behav. 1980;21:219–39.

Rózsa S. Purebl Gy, Susánszky É, Kő N, Szádóczky E, Réthelyi J, et al. A megküzdés dimenziói: a Konfliktusmegoldó Kérdőív hazai adaptációja [Dimensions of coping: Hungarian adaptation of the Ways of Coping Questionnaire]. J Ment Health Psychosom. 2008;9:217–41.

Cook WW, Medley DM. Proposed hostility and Pharisaic-virtue scales for the MMPI. J Appl Psychol. 1954;38:414–8.

Kopp M, Falger P, Appels A, Szedmak S. Depressive symptomatology and vital exhaustion are differentially related to behavioral risk factors for coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:752–8.

Caldwell RA, Pearson JL, Chin RJ. Stress-moderating effects. Pers Soc Psychol B. 1987;13:5–17.

Kopp MS, Skrabski Á. Magyar lelkiállapot [Hungarian state of mind]. Budapest: Végeken Alapítvány; 1992.

Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De La Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804.

Gerevich J, Bácskai E, Rózsa S. A kockázatos alkoholfogyasztás prevalenciája. Psychiatr Hung. 2006;1:45–56.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the other members of the Hungarostudy 2002 team (János Réthelyi, Csilla Csoboth, György Gyukits, János Lőke, Andrea Ódor, Katalin Hajdu, Csilla Raduch, László Szűcs, and Sándor Rózsa), the network of district nurses for the home interviews, Professor András Klinger for the sampling procedure, and the National Population Register for the selection of the sample. This study was supported by OTKA-73754/2008 and ETT-100/2006 grants.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Mária S. Kopp (deceased)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Konkolÿ Thege, B., Pilling, J., Székely, A. et al. Relationship Between Religiosity and Health: Evidence from a Post-communist Country. Int.J. Behav. Med. 20, 477–486 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-012-9258-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-012-9258-x