Abstract

Background

Evidence is accumulating for an association between psychosocial stress and elevated blood pressure. However, studies focusing on adaptive psychosocial factors are scarce.

Purpose

We examined the association between putatively adaptive psychosocial factors and home blood pressure in a population study in the Netherlands.

Method

Resting blood pressure was measured of 985 female and 777 male participants between 20 and 55 years of age in their home setting. Questionnaires assessing problem-focused coping (active coping), adaptive emotion-focused coping (positive reinterpretation) and social support were completed.

Results

When controlled for age, marital and socio-economic status, body mass index, parental history of hypertension, physical exercise, smoking, alcohol, coffee, and—in women—oral contraceptives, positive reinterpretation was associated with a lower prevalence of elevated home blood pressure (≥140/90 mmHg): OR = 0.60, 95% CI = 0.40–0.88 (P = 0.009). Although all three psychosocial variables were associated with both systolic and diastolic blood pressure level, in multivariable analyses, only the associations between systolic blood pressure and positive reinterpretation (β = −0.09, t = 3.25, P = 0.001) and active coping (β = 0.07, t = 2.65, P = 0.008) remained significant.

Conclusion

Independent of other factors, only positive reinterpretation of the situation appeared to be related to more favorable blood pressure levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Psychosocial stress has been hypothesized to be an important risk factor of human essential hypertension [1, 2]. Empirical evidence for the association between psychosocial stress and elevated blood pressure, some of which has been obtained in prospective studies, has been mainly found for daily stress, such as experienced at the workplace (e.g., [3, 4]).

However, up to date, little attention has been paid by researchers to adaptive psychosocial factors that may have a role in counteracting the adverse effects of psychosocial stress [5]. One important exception is social support that has been associated earlier with decreased ambulatory systolic and diastolic blood pressure [6, 7] while a decrease in social support over a period of nine years has been found to be linked with higher hypertension incidence rates in women [8].

Apart from social support, potentially protective psychological factors have hardly been studied in relation to elevated blood pressure, in particular coping styles. In the present study, we focused on two putatively adaptive coping styles, one reflecting problem-focused coping (i.e., active coping), and one being part of the emotion-focused category (i.e., positive reinterpretation). Although problem-focused coping has been suggested to be an adaptive coping style in general, only in one previous study problem-focused active coping was examined in relation to hypertension rates. A tendency for higher hypertension rates was found in those scoring low on work-related problem-focused coping [9].

Positive reinterpretation of stressful situations may be considered an adaptive emotion-focused strategy, which results in a more positive appraisal of the situation and of one’s ability to cope with it [10]. To date, no studies have been reported on the direct association between this coping style and tonic blood pressure levels. However, the appraisal of a stressor and of its consequences is an important determinant of the physiological responses of people to laboratory and daily life stressors, including cardiovascular responses [11, 12]. Milder reactions to these stressors may be associated with a lower risk of hypertension development [13].

Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to evaluate the association between these putatively adaptive psychosocial factors and (1) the prevalence of elevated blood pressure and (2) systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels in a community sample. In addition, we examined whether the associations found would be similar for both sexes, as in several studies lack of social support has been found to be associated with hypertension or correlated with blood pressure levels to a different extent in women and men [6, 14]. A major strength of the current study is that blood pressure measurements were performed at the participants’ homes instead of the clinic, preventing the occurrence of the white-coat effect [15], which threatens the validity of resting blood pressure measurement.

Method

Participants and Procedure

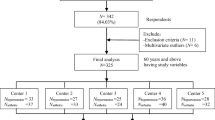

Participants were recruited from three towns in the Mid-Brabant area in southern Netherlands. After a campaign in the local media, street-by-street every household was contacted by telephone for participation. In each household two adults in the age range of 20–55 years could participate. If a person agreed to participate in the study, an appointment was made for the measurement of blood pressure at his or her home and for the delivery of the questionnaire set. People refusing participation were asked about basic demographics (age and sex), and blood pressure status (by means of the question “Do you have elevated blood pressure?”). After the appointment, one week later, the test booklets were recollected.

A total of 2,095 individuals (69.3% of the individuals contacted by telephone) agreed to participate in the study: 1,120 women, 903 men, and 72 persons who did not provide information regarding their sex. Participants who reported to have diabetes mellitus, or any form of kidney or heart disease (N = 59) were excluded from the analyses. In addition, individuals on hypertensive medication who appeared to have normal blood pressure values (24 women and 25 men) were omitted from the analyses because their blood pressure status is unclear. Because of certain psychological characteristics (high anxiety), some of these individuals probably had elevated office readings (“white-coat” hypertension) and anti-hypertensive medication prescribed, while not really having hypertension [16], which biases assessments of associations between psychosocial variables and blood pressure [17]. Due to incomplete or incorrect blood pressure readings (see below; N = 40) and incomplete questionnaire data (N = 176), final (multivariate) analyses were based on 985 women and 777 men.

The study was approved by the institutional review committee of Tilburg University. Informed consent was obtained from the participants at the start of the study.

Blood Pressure Measurements

Blood pressure data were collected in the evening, at the participants’ home using a validated Philips HP 5330 automatic digital device, based on the oscillometric method [18]. The sphygmomanometer used measures blood pressure automatically. Therefore, non-medical collaborators who received a brief training performed the measurements. Because of evidence that the kind of setting (home versus clinic) is more important than the number of measurements on separate days for clinical prognosis [19, 20], four consecutive blood pressure measurements were taken while participants were sitting in a quiet room in their homes, with two-minutes intervals between the measurements. Mean systolic and diastolic pressure (SBP and DBP) were defined as the mean of at least three valid measurements after levels that deviated more than 20% from the mean of the other values were discarded (only 0.8% of the systolic and 0.3% of the diastolic pressures; including these outliers did not change the results presented).

Questionnaires

Perceived social support was measured by a Dutch version of the brief (six-item) Social Support Questionnaire [21]. On five-point Likert scales, ranging from “(almost) never” to “(nearly) always”, respondents indicate the frequency of feeling emotionally and instrumentally supported. An example item is “When I feel down-in-the-dumps, I can count on people that make me feel better”. Both the original scale and the adapted Dutch version have a good internal consistency and validity: Cronbach α ≥ 0.90 for the original [21] and 0.80 for the Dutch version in the present sample.

Active coping and positive reinterpretation were assessed by means of the equally named four-item subscales from the Dutch version of the COPE inventory [10, 22]. Participants answer on four-point Likert scales, ranging from “I usually don’t do this at all” to “I usually do this a lot”, to what extent they engage in the behaviors as reflected by each of the statements. An example item of the Active Coping subscale is “I take additional action to try to get rid of the problem”, while an item of the Positive Reinterpretation scale is “I look for something good in what is happening”. The Dutch version of the subscales has adequate internal consistency (Cronbach α is 0.80 and 0.72, respectively, in the present sample) and validity [10, 22].

In addition, information was collected concerning the following demographic and biobehavioral variables: sex, age, height, weight, marital status, employment status, years of education, smoking, daily coffee intake, weekly alcohol consumption, weekly physical exercise, medication use, and history (own and parental) of hypertension (with onset before the age of 60), diabetes mellitus, and any form of kidney disease.

Statistical Analysis

We tested the associations between the psychosocial variables and both elevated blood pressure and continuous SBP and DBP levels. Elevated blood pressure was defined as having a mean SBP of at least 140 mmHg, or a mean DBP of at least 90 mmHg. Individuals with values below 140/90 mmHg and not using anti-hypertensive medication were used as the reference group in multiple logistic regression analyses predicting blood pressure status. Psychosocial factors were entered as continuous variables to preserve the whole range of scores. In order to facilitate interpretation of the Odds Ratios in the logistic regression analyses, mean instead of sum scores of the items of each scale were used, making the range of scores 1–4 for the coping subscales and 1–5 for social support. For associations with continuous SBP and DBP, multiple linear regression analyses were used.

Analyses were performed twice, with and without the following biomedical, lifestyle, and sociodemographic variables in the analysis at the first step (before the psychosocial predictors): age, body mass index (BMI: weight/(height2)), paternal and maternal history of hypertension, years of education, marital status, employment status, smoking, alcohol and coffee consumption, use of oral contraceptives, physical exercise, and, in the case of the prediction of SBP and DBP, anti-hypertensive medication. Anti-hypertensive medication was not used as a predictor of elevated blood pressure as it was part of the definition of the dependent variable. In addition, to examine potential differential effects for women and men, additional interaction variables were computed being the product of each psychosocial variable by sex, which were included at step 3 of the analyses (after the main effects of the psychosocial variables at step 2).

Results

Descriptives

Respondents were somewhat older than individuals who were not willing or not able to participate in the study: 39.4 ± 8.8 vs. 37.8 ± 9.4, respectively (t = 3.84, P < 0.001). A larger proportion of the respondents reported having elevated blood pressure compared with non-respondents: 9.0% vs. 6.0%, (χ 2 = 5.24, P < 0.05). Both sexes were equally represented in both groups: 56.1% women in the group of non-respondents and 55.6% among the participants (χ 2 = 0.05, P > 0.10).

Applying the current criteria (at least 140 mmHg systolic or 90 mmHg diastolic), 92 (9.3%) women and 123 (15.8%) men were regarded as having elevated home blood pressure. The sample characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 1. Significant differences between people with and those without elevated blood pressure were found regarding age, BMI, and the use of anti-hypertensive medication for both sexes. Parental history of hypertension, lower education and less physical exercise were associated with elevated blood pressure only in women, whereas more alcohol consumption, more years of smoking, and unemployment were associated with elevated blood pressure in men (Table 1).

Elevated Blood Pressure

In the logistic regression analyses including only the psychosocial variables, positive reinterpretation was associated with a lower probability of having elevated blood pressure (OR = 0.47, 95% CI = 0.36–0.67, Wald = 17.63, P < 0.001), whereas for active coping the reverse relationship was obtained (OR = 1.59, 95% CI = 1.15–2.18, Wald = 8.06, P = 0.005). Social support was not associated with elevated blood pressure (P > 0.10), nor was any of the sex × psychosocial variable interaction terms (all P > 0.10).

In the multiple logistic regression analysis, including the biomedical, lifestyle, and sociodemographic variables at step 1, the following variables emerged as significant predictors of elevated blood pressure: age, having no partner, BMI, both paternal and maternal history of hypertension, alcohol consumption, low physical exercise, and the use of oral contraceptives (see Table 2 for the final model). After controlling for these variables, positive reinterpretation was still associated with a lower risk of having elevated blood pressure (OR = 0.60, 95% CI = 0.40–0.88, Wald = 6.91, P = 0.009). The effect of active coping was reduced to a non-significant trend (OR = 1.36, 95% CI = 0.95–1.95, Wald = 2.83, P = 0.093). Social support and the interaction effects with sex were not associated with elevated blood pressure (all P > 0.10).

Systolic Blood Pressure

The multivariate linear regression analysis including only the psychosocial variables revealed small but significant associations with SBP for all three variables: active coping (β = 0.15, t = 5.24, P < 0.001), positive reinterpretation (β = −0.14, t = −4.84, P < 0.001), and social support (β = −0.08, t = −3.47, P = 0.001). When the biomedical, sociodemographic, and lifestyle variables were entered into the equation at step 1, eight variables were significantly associated with SBP: age, sex, having a partner, BMI, paternal and maternal history of hypertension, and use of anti-hypertensive medication and oral contraceptives (see Table 3 for the final model). At step 2, after controlling for these variables, only active coping (β = 0.07, t = 2.65, P = 0.008), and positive reinterpretation (β = −0.09, t = 3.25, P = 0.001) still were significantly associated with SBP levels. Sex × psychosocial variables interactions were not associated with SBP (all P > 0.10) at step 3 of the analysis.

Diastolic Blood Pressure

When only the psychosocial variables were entered into the regression model, all were significantly associated with DBP: active coping (β = 0.10, t = 3.29, P = 0.001), positive reinterpretation (β = −0.08, t = −2.65, P = 0.008), and social support (β = −0.08, t = −3.27, P = 0.001). The analysis including biomedical, sociodemographic, and lifestyle variables at step 1 yielded the following significant predictors of DBP: age, sex, having a partner, BMI, paternal and maternal history of hypertension, alcohol and coffee consumption, exercise, and use of anti-hypertensive medication and oral contraceptives (see Table 4 for the final model). At step 2, no psychosocial variable retained significance (Table 4). Also the sex × psychosocial variable interactions were not associated with DBP (P > 0.10) at step 3 of the analysis.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate the relationship between putatively adaptive psychosocial factors and home blood pressure in a cross-sectional population based study in the Netherlands. The results show that psychosocial factors indeed significantly contributed to the prediction of elevated blood pressure rates as well as systolic blood pressure levels. These relationships were often still significant when controlled for sociodemographic, biomedical, and lifestyle factors. No differential effects were found for women and men. However, the identified effects were not always in the expected direction, which is discussed below.

Most clear associations were found for positive reinterpretation of the situation. This cognitive style was associated with lower rates of elevated blood pressure as well as lower systolic blood pressure levels, even when controlled for potentially confounding variables. This cognitive strategy reflects reappraising the situation in positive terms, an example item being “I look for something good in what is happening” [10]. Such a strategy enhances feelings of being in control, which has been shown in animal research to be a powerful factor reducing stress-related pressure effects [23]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that has examined this adaptive cognitive style in relation to elevated blood pressure. This style is expected to be related to psychological personality traits such as optimism and sense of coherence, which both have been associated with decreased blood pressure levels [24] as well as with buffering stress-related blood pressure increases during laboratory stress tasks [25]. As these psychological traits both also have enhanced feelings of control as central characteristic, it may be hypothesized that this is the main ingredient of their positive effects.

Regarding the problem-focused style of active coping, in contrast to our hypothesis we found a tendency for a positive association with elevated blood pressure and a small, but significant positive association with systolic blood pressure levels, even when controlled for sociodemographic, biomedical, and lifestyle variables. The inconsistency with one previous study reporting a tendency for a negative association between problem-focused coping and hypertension rates [9] may be mainly due to the instruments used to asses this coping style. While our measure reflects a general tendency to cope in an active effortful way to “get around the problem” [10], the measure used by Theorell et al. specifically assesses the tendency to proactively approach a colleague who treats you “in an unfair way”. This is a specific situation, which may be dealt with adequately by proactive problem-focused coping. The general measure of active coping we used might partially tap into an overgeneralized tendency to apply this style across situations, even in those in which the problem really cannot be fixed. This description would fit the so-called John Henryism coping style [26], which, in line with our results, has been shown to be associated with elevated blood pressures in correlational studies in some community sample populations, especially in African Americans of low socio-economic status [26, 27].

Although perceived social support was associated with both lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure, this association disappeared when controlling for sociodemographic, biomedical, and lifestyle variables. In some previous studies, negative associations between social support and blood pressure or hypertension rates were found even when controlled for such confounding variables (e.g., [6, 28, 29]. The type of support assessed and the sample studied are factors that may have a role in the discrepancy with our results. Studies finding negative associations often involved either specific types of support, such as perceived support at work [6] or support from one’s family [29], or specific ethnic groups, such as African Americans [28]. In line with our findings, in some previous studies no associations were obtained between general social support and blood pressure levels [30], or the association disappeared when controlling for sociodemographic and lifestyle variables [31].

Potential mechanisms for the association between psychosocial factors and elevated blood pressure include indirect paths via unfavorable health behavior habits, such as limited physical exercise, overeating, smoking, and alcohol abuse, and direct psychophysiological pathways, such as cardiovascular and endocrine stress reactivity. In our analyses, the potential influence of health behavior habits was controlled and did not diminish the significant effects of coping styles. However, in the present study BMI, smoking and alcohol consumption were assessed by self-reports. In addition, diet was not assessed. This might have underestimated the role of these factors in the present study and, as a consequence, overestimated the role of psychosocial factors. This is a limitation of the present study. In the case of social support, a post-hoc analysis revealed that the disappearance of the associations in the controlled analyses was not due to health behaviors, but to the effect of sex; women scored higher on social support and showed lower blood pressure.

The direct psychophysiological paths that may be involved in the association between psychosocial factors and blood pressure include mechanisms such as sympathetic hyperreactivity, reduced baroreflex gain, and transient endothelial dysfunction during psychosocial stress [32–34]. For instance, recently it has been shown that adaptive psychosocial factors, including a positive reinterpretation facet, are protective against a hyperreactive neuroendocrine system, which is related to hypertension development [35].

Besides the use of self-reports to estimate BMI and health behaviors, the present cross-sectional design is a limitation, not permitting any conclusions regarding the causal nature of the associations found. However, most of our participants had only mildly elevated blood pressures, which usually is asymptomatic. In addition, and more important, most participants in the elevated blood pressure group (62%) did not know they had elevated blood pressure. Therefore, it does not seem very likely that their elevated blood pressure has influenced the psychosocial factor scores. Nevertheless, it is clear that prospective studies are needed to address the issue of causality.

References

Henry JP. Stress, salt and hypertension. Soc Sci Med 1988;26:293–302.

Steptoe A. Psychosocial factors in the development of hypertension. Annals Med 2000;32:371–5.

Greiner BA, Krause N, Ragland D, Fisher JM. Occupational stressors and hypertension: a multi-method study using observer-based job analysis and self-reports in urban transit operators. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:1081–94.

Steptoe A, Willemsen G. The influence of low job control on ambulatory blood pressure and perceived stress over the working day in men and women from the Whitehall II cohort. J Hypertens 2004;22:915–20.

Kubzansky LD, Thurston RC. Emotional vitality and incident coronary heart disease: benefits of healthy psychological functioning. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:1393–401.

Karlin WA, Brondolo E, Schwartz J. Workplace social support and ambulatory cardiovascular activity in New York City traffic agents. Psychosom Med 2003;65:167–76.

Winnubst JA, Marcelissen FH, Kleber RJ. Effects of social support in the stressor–strain relationship: A Dutch sample. Soc Sci Med 1982;16:475–82.

Raikkonen K, Matthews KA, Kuller LH. Trajectory of psychological risk and incident hypertension in middle-aged women. Hypertension 2001;38:798–802.

Theorell T, Alfredsson L, Westerholm P, Falck B. Coping with unfair treatment at work—what is the relationship between coping and hypertension in middle-aged men and Women? An epidemiological study of working men and women in Stockholm (the WOLF study). Psychother Psychosom 2000;69:86–94.

Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989;56:267–83.

Chen E, Matthews KA, Zhou F. Interpretations of ambiguous social situations and cardiovascular responses in adolescents. Annals Behav Med 2007;34:26–36.

Maier KJ, Waldstein SR, Synowski SJ. Relation of cognitive appraisal to cardiovascular reactivity, affect, and task engagement. Annals Behav Med 2003;26:32–41.

Light KC, Girdler SS, Sherwood A, Bragdon EE, Brownley KA, West SG, et al. High stress responsivity predicts later blood pressure only in combination with positive family history and high life stress. Hypertension 1999;33:1458–64.

Yan LL, Liu K, Matthews KA, Daviglus ML, Ferguson TF, Kiefe CI. Psychosocial factors and risk of hypertension: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. JAMA 2003;290:2138–48.

Myers MG, Tobe SW, McKay DW, Bolli P, Hemmelgarn BR, McAlister FA. New algorithm for the diagnosis of hypertension. Am J Hypertens 2005;18:1369–74.

Spruill TM, Pickering TG, Schwartz JE, Mostofsky E, Ogedegbe G, Clemow L, et al. The impact of perceived hypertension status on anxiety and the white coat effect. Annals Behav Med 2007;34:1–9.

Nyklíček I, Vingerhoets AJJM, Van Heck GL. Hypertension and objective and self-reported stressor exposure: a review. J Psychosom Res 1996;40:585–601.

Gompels C, Savage D. Home blood pressure monitoring in diabetes. Arch Dis Child 1992;67:636–9.

Ohkubo T, Asayama K, Kikuya M, Metoki H, Hoshi H, Hashimoto J, et al. How many times should blood pressure be measured at home for better prediction of stroke risk? Ten-year follow-up results from the Ohasama study. J Hypertens 2004;22:1099–104.

Stergiou GS, Baibas NM, Gantzarou AP, Skeva II, Kalkana CB, Roussias LG, et al. Reproducibility of home, ambulatory, and clinic blood pressure: implications for the design of trials for the assessment of antihypertensive drug efficacy. Am J Hypertens 2002;15:101–4.

Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Shearin EN, Pierce GR. A brief measure of social support: Practical and theoretical implications. J Soc Pers Relatsh 1987;4:497–510.

Kleijn WC, van Heck GL, van Waning A. Ervaringen met een Nederlandse bewerking van de COPE copingvragenlijst: De COPE-Easy [Experiences with a Dutch adaptation of the COPE coping questionnaire: The COPE-Easy]. Gedrag Gezond 2000;28:213–26.

Cox RH, Hubbard JW, Lawler JE, Sanders BJ, Mitchell VP. Exercise training attenuates stress-induced hypertension in the rat. Hypertension 1985;7:747–51.

Lindfors P, Lundberg O, Lundberg U. Sense of coherence and biomarkers of health in 43-year-old women. Int J Behav Med 2005;12:98–102.

Clark R, Benkert RA, Flack JM. Violence exposure and optimism predict task-induced changes in blood pressure and pulse rate in a normotensive sample of inner-city black youth. Psychosom Med 2006;68:73–9.

James SA, Hartnett SA, Kalsbeek WD. John Henryism and blood pressure differences among black men. J Behav Med 1983;6:259–78.

Fernander AF, Duran RE, Saab PG, Schneiderman N. John Henry Active Coping, education, and blood pressure among urban blacks. J Natl Med Assoc 2004;96:246–55.

Strogatz DS, Croft JB, James SA, Keenan NL, Browning SR, Garrett JM, et al. Social support, stress, and blood pressure in black adults. Epidemiology 1997;8:482–7.

Tomaka J, Thompson S, Palacios R. The relation of social isolation, loneliness, and social support to disease outcomes among the elderly. J Aging Health 2006;18:359–84.

Pollard TM, Carlin LE, Bhopal R, Unwin N, White M, Fischbacher C. Social networks and coronary heart disease risk factors in South Asians and Europeans in the UK. Ethn Health 2003;8:263–75.

Strogatz DS, James SA. Social support and hypertension among blacks and whites in a rural, southern community. Am J Epidemiol 1986;124:949–56.

Ghiadoni L, Donald AE, Cropley M, Mullen MJ, Oakley G, Taylor M, et al. Mental stress induces transient endothelial dysfunction in humans. Circulation 2000;102:2473–8.

Julius S. Corcoran Lecture. Sympathetic hyperactivity and coronary risk in hypertension. Hypertension 1993;21:886–93.

Lucini D, Norbiato G, Clerici M, Pagani M. Hemodynamic and autonomic adjustments to real life stress conditions in humans. Hypertension 2002;39:184–8.

Wirtz PH, von Känel R, Mohiyeddini C, Emini L, Ruedisueli K, Groessbauer S, et al. Low social support and poor emotional regulation are associated with increased stress hormone reactivity to mental stress in systemic hypertension. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:3857–65.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Nyklíček, I., Vingerhoets, A. ‘Adaptive’ Psychosocial Factors in Relation to Home Blood Pressure: A Study in the General Population of Southern Netherlands. Int.J. Behav. Med. 16, 212–218 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-008-9019-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-008-9019-z