Abstract

Digital assistants (DA) perform routine tasks for users by interacting with the Internet of Things (IoT) devices and digital services. To do so, such assistants rely heavily on personal data, e.g. to provide personalized responses. This leads to privacy concerns for users and makes privacy features an important component of digital assistants.

This study examines user preferences for three attributes of the design of privacy features in digital assistants, namely (1) the amount of information on personal data that is shown to the user, (2) explainability of the DA’s decision, and (3) the degree of gamification of the user interface (UI). In addition, it estimates users’ willingness to pay (WTP) for different versions of privacy features.

The results for the full sample show that users prefer to understand the rationale behind the DA’s decisions based on the personal information involved, while being given information about the potential impacts of disclosing specific data. Further, the results indicate that users prefer to interact with the DA’s privacy features in a serious game. For this product, users are willing to pay €21.39 per month. In general, a playful design of privacy features is strongly preferred, as users are willing to pay 23.8% more compared to an option without any gamified elements. A detailed analysis identifies two customer clusters “Best Agers” and “DA Advocates”, which differ mainly in their average age and willingness to pay. Further, “DA Advocates” are mainly male and more privacy sensitive, whereas “Best Agers” show a higher affinity for a playful design of privacy features.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) offers a plethora of new possibilities in society and the economy. Digital assistants (DA) are one way to support users to adopt IoT applications and manage the ever increasing number of interconnected devices (Maedche et al. 2019). One possible application of a DA, for example, is that a DA automatically sets the house heating system to the user’s preferred temperature as soon as he or she is on the way home. To provide comprehensive user assistance, the DA needs to process a large amount of personal information, such as preferences, appointments and current location data. However, this poses privacy risks, because assistants extensively track and process personal data often without the user’s knowledge or control after the initial consent given by the user (Knote et al. 2019). Ultimately, this leads to a privacy “black box”, because the algorithms are invisible and incomprehensible to users (Pasquale 2015; Fischer and Petersen 2018).

This is more than a purely hypothetical risk, as reports on recent privacy incidents involving IoT devices and DAs have shown. For example, voice assistants are always in listening-mode and are prone to mishear their wake word and start unintended interactions (McLean and Osei-Frimpong 2019). Even more privacy violating, Apple’s Siri recorded confidential information about medical details and couples having sex and external contractors listened to these audio files as part of a quality control process (Hern 2019). Other IoT devices, such as smart TVs, have privacy-violating default settings (Bundeskartellamt 2020).

While there are different reasons why individuals use digital assistants (such as utilitarian, symbolic or social benefits), perceived privacy risks are negatively influencing the adoption of IoT assistants (Brill et al. 2019; McLean and Osei-Frimpong 2019; Menard and Bott 2018). These risks include the pervasive collection and analysis of personal data that can invoke privacy concerns (Maedche et al. 2019) in cultures subscribing to the concept of informational self-determination (Federal Constitutional Court 1983). This leads to a situation in which users are “increasingly challenged with managing the complex trade-offs of technology innovation with the risks of information privacy concerns” (Brill et al. 2019, p. 17). These concerns have grown significantly in recent years (GlobalWebIndex 2019).

One potential remedy are privacy features of DAs that can actively support the user in making privacy decisions or adjust settings based on the user’s privacy preferences (Liu et al. 2016). Prior research has focused mainly on the technical, operational and cryptographic characteristics of privacy features (Mihale-Wilson et al. 2017; Zibuschka et al. 2016). Although user interfaces are another important feature of information systems (Acquisti et al. 2017) and a “fruitful avenue for human–computer interaction” (Maedche et al. 2019, p. 539), to the bets of our knowledge, there is no study that examines user preferences with respect to the design of privacy features. To bridge this gap, our study addresses the following research question: What are prospective end-users’ preferences regarding the design of privacy features of a digital assistant, and what are they willing to pay for different variants?

We explore three key attributes: (1) A playful design manifested in the degree of gamification of the user interface (UI), because it influences the acceptance of new technology (Davis 1989) and can help “to overcome decision complexity” (Acquisti et al. 2017, p. 11). (2) The amount of information about personal data a DA uses that is presented to the user, because it is important to find the trade-off between too much and too little information (Galitz 2007). (3) The basis on which a DA’s decisions should be explained to foster user acceptance and trust (Ribeiro et al. 2016; Förster et al. 2020). As privacy protection can have an economic effects in terms of costs, we additionally calculate the users’ willingness to pay (WTP) for different feature combinations. This allows for an informed development of DAs that are likely to meet the market’s needs.

This paper is structured as follows: In Section 2, we introduce the theoretical background on privacy and review previous studies that attempted to create usable privacy tools. The section continues with an introduction to privacy assistants. Section 3 explains our methodology, while Section 4 presents the results of a choice-based conjoint analysis (CBC), and Section 5 discusses the implications for theory and practice. Section 6 concludes with the implications of our findings for researchers and practitioners.

Related work

To underline the importance of privacy for end-users, this section summarizes the literature on users’ privacy perception and an economic perspective of privacy. It describes how current digital assistants incorporate privacy features to address the need for data transparency. Prior work on usable privacy interfaces is presented, focusing on playful interactions, i.e. gamification and serious games. It concludes with the insights into user privacy preferences and defines the research gap.

Users’ privacy perceptions and privacy assistance

Privacy has different meanings in different disciplines, cultures and individuals (Smith et al. 2011; Rho et al. 2018). Information privacy is a subset of privacy that “concerns access to individually identifiable personal information” (Smith et al. 2011, p. 990). Accompanied by developments in information technologies, information privacy has become a main focus of information system (IS) research (Smith et al. 2011). However, no comprehensive definition has been made so far (Smith et al. 2011). In this paper, we build upon the notion of informational self-determination as defined by the German Federal Constitutional Court (1983) and enshrined in the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

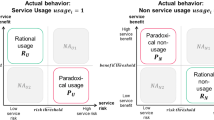

Missing trust is an antecedent of privacy concerns (Smith et al. 2011). Together with prior experience in information systems, trust can “have a significant influence on the intention to disclose information” (Kumar et al. 2018, p. 631). With advances in information technology, privacy concerns have been raised in different domains (Bélanger and Crossler 2011; Goldfarb and Tucker 2012). For example the impact of trust in DAs was examined by Mihale-Wilson et al. (2017). Further, these concerns can be external and internal: External, because digital assistants are software-based and hackers can exploit security vulnerabilities and access personal information (Biswas and Mukhopadhyay 2018). Internal, because DAs need a substantial amount of personal data for a meaningful personalization. There is a conflict here for users between maintaining their privacy and benefiting from personalization, which is called the “personalization-privacy paradox” Sutanto et al. (2013). In general, users feel the need to have control over their privacy (GlobalWebIndex 2019; Bélanger and Crossler 2011), which often includes users’ risk assessment (Kehr et al. 2015). However, in the field of IoT, many users are often unaware that their devices are able to intrude upon their privacy (Lopez et al. 2017; Manikonda et al. 2018).

As digital assistants rely heavily on personal data, there is always a threat to the user’s privacy (Maedche et al. 2019; Saffarizadeh et al. 2017). But there are different attacker models. Strangers with physical access to a smart speaker could ask questions that reveal sensitive details about the owner of the device (Hoy 2018). For example, a study of Amazon’s Alexa revealed that attackers can access usage patterns, user’s interests, shopping lists, schedules and driving routes (Chung and Lee 2018). With the omnipresence of connected devices, ever more data could be disclosed (Liu et al. 2017). It is becoming increasingly difficult for end-users to manage their privacy, for example, because the DA feature a large number and variety of configurable privacy controls, which make it difficult for users to align their preferences (Liu et al. 2016). Further, users do not understand the underlying algorithms (Fischer and Petersen 2018).

Privacy assistants are meant to help users manage their privacy (Das et al. 2018). These assistants can control and visualize the data streams from different devices and are capable of learning users’ privacy preferences (Liu et al. 2016). Several authors have developed privacy assistants that actively support users. For example, Andrade and Zorzo (2019) present “Privacy Everywhere”, a mechanism that processes IoT data before it is sent to the cloud, in order to allow users to decide whether or not to disclose it. In the same domain, Das et al. (2018) develop an assistant that predicts user privacy preferences. Other domains include smartphones (e.g. Liu et al. 2016) or smart buildings (e.g. Pappachan et al. 2017). However, none of these studies focuses on the user interface to control or understand privacy settings.

Users’ privacy preferences and their economic value

Understanding privacy preferences is important for business (as it can be a competitive advantage), for legal scholars (as privacy is becoming increasingly prominent), and for policy makers (to identify desirable goals) (Acquisti et al. 2013). Accordingly, much research has been done on preferences in different domains. In the field of home assistants, Fruchter and Liccardi (2018, p. 1) identify “data collection and scope, ‘creepy’ device behavior, and violations of personal privacy thresholds” as major user concerns. Other work focuses on preferences related to mobile devices. Emami-Naeini et al. (2017) are able to predict privacy preferences with an accuracy of 86%, while “observing individual decisions in just three data-collection scenarios”. Similarly, Liu et al. (2016) use a smartphone app to identify user preferences and create privacy profiles over time. Lin et al. (2012, p. 501) use “crowdsourcing to capture users’ expectations of what sensitive resources mobile apps use”. Das et al. (2018) apply machine learning to predict user preferences. However, privacy preferences are subjective and difficult to assess (Acquisti et al. 2013), depend on data type and retention time (Emami-Naeini et al. 2017), and change over time (Goldfarb and Tucker 2012). These preferences influence system adoption (McLean and Osei-Frimpong 2019).

On the one hand, users value “privacy as a good in itself” (Acquisti et al. 2016, p. 447) and are confronted with trade-offs between privacy and functionality when using a DA. On the other hand, users are willing to disclose information for monetary incentives (Hui et al. 2007). Whereas privacy is often seen as an imperfect information asymmetry between consumers and companies (Acquisti et al. 2016), Jann and Schottmüller (2020) disprove this view by calculating situations where privacy can even be Pareto-optimal.

A recent study by Cisco (2020, p. 3) found that “more than 40% [of the surveyed companies] are seeing benefits at least twice that of their privacy spend”. Nonetheless, privacy “is one of the most pressing issues” (Jann and Schottmüller 2020, p. 93) for companies. To help them anticipate financial gains, several researchers use conjoint analyses to estimate users’ willingness-to-pay (WTP) for different privacy features (e.g. Mihale-Wilson et al. 2019; Roßnagel et al. 2014). In the field of online storage, Naous and Legner (2019, p. 363) perform a conjoint analysis and find that “users are unwilling to pay for additional security and privacy protection features”. Derikx et al. (2016) find that users of connected cars give up their privacy concerns towards the insurance company for minor financial compensations. In the field of DA, Zibuschka et al. (2016) conduct a user study and investigate three key attributes, namely data access control, transparency, and processing location. Using a choice-based conjoint (CBC) analysis, they find that users are willing to pay 19.97 €/month for an assistant offering intelligent data access control to the servers of the manufacturer while providing intelligent transparency notices. A similar approach, but with different attributes, is conducted by Mihale-Wilson et al. (2017). They find users prefer a DA with full encryption with distributed storage certified by a third party auditor, and have a WTP of 25.85 €/month.

Usable privacy interfaces

Several authors conduct studies on privacy and usability in prototypical settings (e.g. Adjerid et al. 2013; Cranor et al. 2006; Wu et al. 2020). Acquisti et al. (2017, p. 11) and emphasize the importance “to overcome decision complexity through the design of interfaces that offer users […] easy-to-understand options”. Bosua et al. (2017, p. 91) stress the importance of nudges “as a warning or intervention that can support users in making decisions to disclose relevant or more or less information”. Most personal assistants today use voice commands to interact with the user. However, Easwara Moorthy and Vu (2015) found that users prefer not to deal with personal information via voice-controlled assistants. Instead, privacy interfaces could be facilitated using gamification the usage of “game-like elements in a non-game context” (Deterding et al. 2011, p. 9). Examples for such elements include scoring systems or badges that can be obtained by the user of an information system and that foster motivation (Blohm and Leimeister 2013). Other interfaces, so-called serious games, are fully-fledged games using game mechanics in a non-entertainment environment (Blohm and Leimeister 2013). For example, Zynga visualized their privacy policy until 2017 and let the user walk around in “PrivacyVille” to explore how user data is processed (Ogg 2011).

Various domains now use gamification and serious games. For example, health and fitness apps encourage users to do their workout (Huotari and Hamari 2017). In e-learning systems, users earn points for answering questions correctly (Aparicio et al. 2019). In user authentication research, users are presented with a chess-like playing field and playing tokens. They progress through the playing field and choose a path which is then converted into a login path that represents a secure password (Ebbers and Brune 2016). However, so far, very little research has been conducted on gamification as a means for controlling and understanding privacy settings.

Privacy information provisioning

Besides playful elements, the proper amount of information is an important element of user interfaces. Whereas too much information can confuse users, too little information is “inefficient and may tax a person’s memory” (Galitz 2007, p. 181). In the field of personal data, privacy policies are commonly used to inform users how their information is threatened. As stated in Article 12 GDPR, the vendor must provide this information in a “concise, transparent, intelligible and easily accessible form, using clear and plain language” (European Parliament and Council 2018). However, many privacy policies are too long and difficult to read. For example, users would have to spend 244 h each year just to read the privacy policies of every website they visit (Gluck et al. 2016). To lower users’ effort and raise awareness, some researchers attempt to visualize privacy policies (Soumelidou and Tsohou 2020). For example, “The Usable Privacy Policy Project” coordinated by Prof. Sadeh and Prof. Acquisti has been tackling this problem since 2013 (Carnegie Mellon University 2017). Moreover, Cranor et al. (2006, p. 135) develop user interfaces based on a “standard machine-readable format for website privacy policies”.

Additionally, a prospective threat analysis of possible privacy-related functions could be useful for individuals (Friedewald and Pohoryles 2016). We consider this a privacy impact assessment by end-users. There is much research about the possible threats of information sharing, e.g. location data used for location-based advertising (Crossler and Bélanger 2019) or even to identify a user’s home address (Drakonakis et al. 2019) or revealing shopping behavior helping marketing companies to identify someone as pregnant before even family members know (Hill 2012). A DA could show such examples to the user, e.g. as soon as an IoT device asks to be granted location access.

Explainable decisions of digital assistants

Decision-making is often a process of mutual cooperation between humans and DAs (Maedche et al. 2019). Digital assistants can use artificial intelligence (AI) to make recommendations or even autonomous decisions based on the stored data. However, this decision-making process is invisible to users and so they often mistrust or do not accept AI (Ribeiro et al. 2016). Accordingly, the European Commission (2019) calls for understandable and “trustworthy AI”. To provide greater visibility, there are different ways decisions could be explained. For instance based on the underlying algorithm (Gunaratne et al. 2018) or based on the data involved (Kuehl et al. 2020; Miller et al. 2019). While Förster et al. (2020) conduct a study to identify user preferences for different types of explanation, they do not ask what the explanation should be based on. Whereas data-based explanations could be especially interesting when interacting with personal data, studies on the acceptance of the Corona tracing app in Germany show that some users are also interested in a deeper understanding of the underlying algorithm and processes (Buder et al. 2020). We provide a comprehensible example of these attributes in the “Concept Selection” section.

Research gap

The body of literature on DAs is rich. However, the customer’s attitude towards privacy features, in particular the user interface, and their willingness to pay for such features is scarce. Whereas several researchers identify user preferences concerning technical and organizational privacy features of digital assistants, preferences towards the user interface design are not studied. Different possible features, such as explainable AI, the amount of information and the degree of gamification have only been studied separately and absent from privacy. We close this gap by combining these elements and identify feature combinations that are preferred by prospective users.

Research method

This study aims to identify user preferences for the design of the DA’s interface for controlling and understanding privacy settings. More specifically, we investigate preferences concerning the amount of background information about personal data that is shown to the user, the explainability of the assistant’s decisions, and the degree of gamification of the DA’s interface.

Figure 1 shows our research design. It is divided into three stages as proposed by Chapman et al. (2008). Prior to the first stage, we performed a literature review of privacy features for assistants. Then, in “concept selection”, we relied on a panel of qualified experts to choose the attributes. Next, we tested the validity and understandability of these features in a first questionnaire, which was presented to a non-expert sample of users but who are potential users of such a DA. In the second “study refinement” stage (originally called “product refinement”), we conducted a representative user study in which we presented choice sets of different privacy assistants with different prices to users (Gensler et al. 2012). In the final stage, we analyzed the CBC results.

Literature search

We conducted an iterative literature search in journals of the AIS Basket of Eight using the search engine Scopus, limited to English and German publications from 2000 or later. As our research question concerns user interaction, we also included the journals from the SIG HCI. Further, as privacy is an interdisciplinary concept, we searched in Google Scholar while prioritizing papers with the highest number of citations. We came across the “Personalized Privacy Assistant Project”,Footnote 1 reviewed their publications and conduced a forward- and backward-search. The keywords and precise search process can be found in the online “Appendix 2” (see file “Appendix 2_LiteratureReviewProcess.pdf”, which will be submitted as an online appendix). We started to search for general information privacy literature, then technical features and characteristics of current DAs, and lastly combined both search topics to find features that have privacy implications. In total, we identified 16 attributes with three attribute levels for each. One example is the way prospective users could communicate with the DA: text-based, image-based or voice-based (Knote et al. 2019). (The full list can be found in Appendix 1_ListOfKeyAttributes.pdf, which will be submitted as an online appendix.)

“Concept selection”: Identifying three key attributes for the user Interface’s interaction with the digital assistant

Following Chapman et al. (2008), in this stage, we held informal talks with five experts (three with a doctoral degree, one professor, and one with significant industry experience in the domain of privacy and assistance systems). We chose this method, because it answers “questions that commonly arise in early-phase user research for new technology products” (Chapman et al. 2008, p. 37). This is very suitable for us because the features of the assistant in our study can be regarded as new technology products. We aimed at identifying three key attributes and the corresponding attribute levels as a limit to avoid “biased or noisy results” (Johnson and Orme 1996, p. 1) and to keep the CBC convenient. We informed the experts of the user-centric perspective as a decision criterion. Further, the experts selected attributes based on practical relevance, as well as their feasibility and applicability for a multinational technology company active in the IoT field, among others. In addition, we gave the experts the opportunity to suggest alternative wordings. After several rounds of coordination, the experts agreed on the key attributes and their corresponding attribute levels (see Table 1).

For the “explainability of the assistant’s decisions” attribute, the assistant could explain decisions on three distinct levels of detail: (1) No explanation means that the assistant just presents its decision. For example, while en route to a destination, the assistant guides the user to a gas station if the vehicle needs refueling. (2) The assistant explains its decision by presenting the data used as a basis. For example, the assistant guides the user to a specific gas station and displays the symbol of a loyalty card. The user concludes that the DA chose this gas station because she owns the respective loyalty card and can earn loyalty points. (3) In addition to the data basis, the assistant explains the underlying algorithm of the assistant’s decision. For example, it shows the current tank level and current gas consumption and calculates the maximum travel distance still possible. Then the assistant shows a circle on a map with the diameter of the travel distance and highlights gas stations within it. In addition, it shows the calculation of expected loyalty points depending on the fueled liters.

The attribute “amount of presented information” covers the scope and effect of data processing and features the following levels. (1) Users are presented with text directly from the privacy policy. For example, the assistant could be granted general permission to access the user’s gallery while using the systems of a third party. (2) Besides the privacy policy, there is a visual explanation of data usage. For example, the assistant shows if and how often the gallery is accessed. (3) Users are offered a prospective analysis about the possible impacts of data disclosure. For example, the assistant informs the user that it is possible to access location data stored in the images.

The attribute “degree of gamification of the UI” can offer (1) no playful elements, i.e. a standard interface. (2) Gamified elements can award users points for blocking devices’ privacy-violating permissions. (3) A serious game can represent user devices and interactions in an immersive game world. For example, users can block a washing machine’s network access with virtual scissors as an avatar. Fig. 2 shows these different interface options.

Price is our fourth attribute. It helps us to elicit the WTP of users, which is defined as the “price at which a consumer is indifferent between purchasing and not purchasing” (Gensler et al. 2012, p. 368). According to Schlereth and Skiera (2009), prices should be chosen in a way that means the respondents are not subject to extreme choice behavior, which would result if they always chose or never chose the no-purchase option. To avoid this issue, we followed the approach of Gensler et al. (2012), which says that a good study design should offer low and high price levels to enforce choices and no-choices. We suggested different price levels to the expert panel based on prior price levels in related studies (Krasnova et al. 2009; Mihale-Wilson et al. 2017; Mihale-Wilson et al. 2019; Roßnagel et al. 2014; Zibuschka et al. 2016). Based on a joint discussion with regard to technical feasibility and potential development costs, they suggested four subscription prices: 5, 10, 30 and 59 €/month. This is a common approach, but there is no guarantee that it covers the full range of possible WTP (Gensler et al. 2012).

Next, we conducted a moderated survey (n = 20) to verify the understandability of the three attributes and attribute levels. Further, we aimed at descriptive results for possible usage domains and reasons for using privacy features. We employed a paper questionnaire and asked participants to think aloud while completing it. The insights served as the basis for the final survey.

“Study refinement”: Representative user study

In the “study refinement” phase (Chapman et al. 2008), we carried out a CBC survey. We chose this method because it is “a useful methodology for representing the structure of consumer preferences” (Green and Srinivasan 1978, p. 120), can present easy-to-imagine products to prospective users (Desarbo et al. 1995), and is widely used in information systems and market research (Miller et al. 2011). Further, it allows us to evaluate the prospective user valuation of certain product features using statistical measures (Gensler et al. 2012). In our CBC, participants chose from among 15 choice sets of different versions of the design of a DA’s privacy features with different prices, including a no-purchase option. We used the Sawtooth Software to obtain an optimal design. We also ran a pre-test to ensure that users understand the different attribute levels before offering the survey to the full sample. The CBC surveyFootnote 2 comprised four steps:

-

1.

Introductory video-clip: We showed a five-minute video clip in English (with German subtitles) to introduce digital assistants and to demonstrate their possible use in the normal workday of a fictive employee called Henry. This video was originally created for the marketing purposes of a multinational firm and did not relate to our three identified attributes directly. Instead, its aim was to help users see what data a DA uses and perhaps make them start to think about possible privacy threats. Users were not able to skip the video clip as the “next”-button appeared only after the video had ended.

The video showed the following use cases:

-

The assistant wakes the user earlier than scheduled to inform him of a traffic jam forecast on his way to the office. Thus, the user decides to work from home and asks the assistant to inform his colleagues in the office.

-

As the day goes on, the assistant informs Henry that his grandmother is unwell and advises him to buy medicine.

-

When leaving the house, the DA reminds Henry to take his key.

-

When the postal worker rings at the door, Henry allows the assistant to disable the alarm system and open the door for sixty seconds.

-

The DA warns that the dryer might have a malfunction and suggests sending diagnostic data to the maintenance service.

-

2.

Descriptive text: After the video clip, descriptive text informed the user that the DA needs personal data to provide such functionalities.

-

3.

Introduction of different privacy features: We introduced several versions of the DA that differ with regard to the design of privacy features. In the next step, we explained these design features and the three identified key attributes. We provided a description and examples for each attribute level.

-

4.

Users start choice-based conjoint survey: Table 2 shows an example of a choice set.

“Customer definition”: Analyzing demographic and psychographic information

In the “customer definition” stage (Chapman et al. 2008), we enlisted the help of a market research company to investigate a sample of the German population that is representative with regard to demographics, specifically gender and age distribution. We predefined a sample size of 300 participants, as this is a common number for representative user studies in this domain (e.g. Gensler et al. 2012).

We elicited demographic (e.g. age, education, etc.) and psychographic (e.g. risk tolerance, technology affinity and playfulness) information. This is needed to better understand users’ decisions and to identify consumer groups as a basis for further market segmentation. To do so, we applied established scales to the evaluation of our psychographic variables, such as Steenkamp and Gielens (2003) for the users’ attitude towards innovation, Meuter et al. (2005) for measuring the participants’ technology affinity, and Taylor (2003) and Westin (1967) for examining privacy concerns. The interaction of the user, originally from Serenko and Turel (2007), was adapted to the usage of DAs and showed similar reliability scores.

Evaluating the participants’ willingness to pay

The WTP can be interpreted as the threshold at which a user is indifferent to purchasing or not purchasing (Gensler et al. 2012). In CBC, consumers repeatedly pick their preferred variation of a product. The underlying assumption is that a user chooses the product that yields the highest personal utility. The no-purchase option helps us to determine unpopular product variants. This information can be used to calculate the WTP. (1) describes the probability that individual h chooses a specific feature version i, from a choice set a (Gensler et al. 2012).

Where

- Ph,i :

-

probability that consumer h chooses product i from choice set a.

- uh,i :

-

consumer h’s utility level of product i.

- uh,NP :

-

consumer h’s utility level of the no-purchase option.

- uh,i’ :

-

consumer h’s utility level of all presented products.

- H :

-

index set of consumers.

- A :

-

index set of choice sets.

- I :

-

index set of products.

- Ia :

-

index set of products in choice set a, excluding the no-purchase option.

The parameters in (1) can vary, because the WTP differs across consumers. Thus, we used hierarchical Bayes to derive individual parameters (Karniouchina et al. 2009; Andrews et al. 2002). We can use information about prior segment membership probabilities to derive individual parameters based on estimated segment-specific parameters by employing a latent class multinomial logit (MNL) model, which maximizes the likelihood function (Wedel and Kamakura 2000). We can gain information about the user’s WTP by deriving individual parameters for the product attributes (βh,j,m), price (βh,price), and no-purchase option (βbh,NP) (Moorthy et al. 1997).

Rearranged (2):

The individual h’s utility for product i is the sum of the partial utilities supplied by the product attributes and price (4):

with

- uh,i:

-

consumer h’s utility level of product i.

- J:

-

index set of product attributes excluding price.

- Mj:

-

index set of alternatives for the attribute j.

- ßh,j,m:

-

consumer h’s parameter for the alternative m of the attribute j.

- xi,j,m:

-

binary variable indicating if product i features the level m of the attribute j.

- ßh,price:

-

consumer h’s price parameter.

- pi:

-

price for product i.

We can define the WTP as the price point at which a user is indifferent towards purchasing or not purchasing a version (5). Then we can deduce WTP as follows (6):

where ßh,NP is consumer h’s utility from choosing the no-purchase option.

We can estimate individual parameters for the product attributes, price, and the no-purchase option (i.e. ßh,j,m, ßh,price, ßh,NP) based on the CBC output and formulas (1) and (4). Accordingly, we can calculate the overall WTP (6) for each of the presented DA versions (Moorthy et al. 1997).

Results

In total, n = 303 persons completed the survey. Table 3 presents their descriptive statistics. These are representative for the population of German Internet users. Gender is evenly split. Age ranges from 18 to 69, with the majority between 35 and 54, still mirroring the overall population. Around 60% of the participants are in a relationship or married. The educational level is high with a majority of participants possessing a university entry qualification (38%) or university degree (35%). Nearly half of the participants are full-time employees (46%) with a monthly income ranging from €501 to €2500 (54%).

We identified three segments based on the CBC analysis: (1) “always purchasers” (18.8%), (2) “sometimes purchasers” [buy at least one version] (37.6%) and (3) “non-purchasers” (43.6%). The collected psychographics were used to identify two different clusters. To analyze this information, we used established measures from psychology, marketing and information systems. We used Cronbach’s alpha to measure internal consistency and estimate the reliability of psychometric tests (Cronbach 1951), e.g. technology anxiety 0.93 (0.93 in previous studies by Meuter et al. (2005)), risk-taking 0.90 (0.84 in previous studies by Jackson (1976)) and playfulness, adopted to the usage of DA, 0.78 (0.77 in previous studies by Serenko and Turel (2007)). In addition, we conducted a CFA to calculate the overall model fit and found an adequate fit: RMSEA = 0.068, CFI = 0.948, TLI = 0.896 (Schreiber et al. 2006). Examining the demographic and psychographic data of the segment “always purchasers” revealed that these are young, privacy-concerned and risk-seeking. Non-purchasers are around 50 years old, less educated and less risk-seeking.

Gensler et al. (2012) suggest focusing on the subset of respondents who do not display extreme choice behavior, (“always purchasing” and “never purchasing”), to be able to calculate meaningful WTPs. Otherwise, users who state they are willing to pay a preposterously high or low price lead to high bias in the WTP estimates. Following this approach, we excluded 132 non-purchasers and 57 always-purchasers from the WTP and cluster analysis to produce reliable WTP estimates. Participants who spent less time completing the survey than a pre-identified mean completion time were excluded prior to creating the sample.

Preferences of the full sample

We considered the different feature variants for the full participant’s sample. Table 4 shows the top feature variants. This ranking is based on the users’ WTP. The most preferred variant (1st ranking) is an assistant that explains its decisions with regard to the data basis, offering information about possible impacts from the disclosure of a specific piece of information while interacting with the user as a serious game. Users were willing to pay 21.39 €/month for this product variant.

We found that participants prefer comprehensive information about the treatment of their personal data. This matches prior findings, e.g. BVDW (2019). There is strong evidence that consumers want an explanation of a DA’s decision based on the data involved. Users do not want the algorithm explained in detail, a variant that ranks only sixth. This seems plausible, as users tend to not understand algorithms. Data should be presented in a visual way, e.g. using icons or diagrams. Further, a majority of users prefer a prospective analysis. Only few respondents (rank 5) consider a textual presentation (privacy policy) to be adequate as an explanation for the effects and scope of data processing. This might be due to the fact that privacy policies are often considered too long and difficult to read (Gluck et al. 2016). In addition, users value playful interaction with the assistant’s privacy features. This can be achieved either by using gamified elements or by developing a serious game. A DA with no gamified elements only ranks thirteenth. With regard to costs, users are willing to pay 23.8% more compared to an option without any gamified elements (€21.39 vs. €16.29). Thus, our findings illustrate the potential value of gamified elements when it comes to designing the privacy features of a DA.

Preferences of two customer clusters

We clustered demographic and psychographic information by interpreting the graphical representation using the elbow criterion (Ketchen and Shook 1996). With regard to practical relevance, the results suggested grouping the respondents into two customer clusters. Based on their attributes, we call these clusters “Best Agers” and “DA Advocates” (see Table 5). They differ mainly in their average age (55 vs. 32 years) and willingness to pay (17.15 vs. 24.84). “DA Advocates” have a higher education and are mainly male. In addition, they are more privacy sensitive (3.64), show a higher risk appetite (3.53), and are slightly more willing to innovate (3.89 compared to 3.80 for “Best Agers”) on a seven-point Likert scale. It is noticeable that “Best Agers” show a higher affinity for playfulness (5.04) than “DA Advocates” (4.75).

Table 6 shows the top three preferred versions for both customer clusters, ranked by price. The “Best Agers” prefer an explanation based on data. In addition, they like to interact with the DA in the form of a serious game. The amount of information varies from “prospective analysis” (first), to visualization (second) and policy (third). With regard to their WTP, “Best Agers” pay on average 12.82 €/month over all feature variants. “DA Advocates” have similar preferences, but show a significantly higher averaged WTP (15.32 €/month). Again, they prefer an explanation based on data. Prospective analysis ranks first and second for the amount of information. Visualization ranks third. Participants prefer gamified elements or a serious game for interaction with the assistant.

Discussion

To answer the research question, we examined users’ preferred way to control and understand the privacy settings of a digital assistant and their willingness to pay for their favorite version. Hence, our CBC analysis offers insights from an end-user perspective. The study takes into account insights from previous research on information privacy and introduces different user interface elements to elicit privacy preferences. Our main contribution is to deepen the understanding of the emerging application fields of gamification and digital assistance for privacy. In the next sections, we will give a more in-depth description of our contribution.

Implications for theory

First, our detailed analyses reveal that the population is not very homogeneous with respect to digital assistants in the area explored: Overall, we find three segments and identify two further clusters in the main segment, which we explore in more depth. The first segment would buy any of our proposed systems at the selected prices. We call this segment “always purchasers”, and it comprises prospective users who are mainly young and risk-seeking – a trait that is commonly linked to younger people – but interestingly have privacy concerns at the same time. This seems a contradiction to some extent and could warrant further research. This segment shows a very high willingness to pay and seems to value DA in general, although privacy is important to them. These “always purchasers” make up 18.8% of our sample. The second segment identified by the CBC is not interested in any of the proposed assistants (we called this segment “non-purchasers”, and they comprise about 43.6% of the sample). This segment consists of older people who have a lower level of education on average and may lack the financial means to purchase a DA at the given price levels.

The main segment, which we examine in detail, consists of prospective users, who would adopt one of the systems depending on cost and the features offered. This main segment consists of two clusters that could play a pivotal role in the market success of digital assistants. The first cluster, which we call “Best Agers” are prospective users aged around 55 years on average with a slightly lower willingness to pay for the systems (around 17 €/month). Price differentiation could be used to appeal to this group by offering special discounts for pensioners and early retirees. Interestingly, these “Best Agers” have a pronounced tendency for gamification. They are willing to adopt the new technology, but strongly prefer a serious game that explains potential privacy threats and allows them to set privacy settings in a gamified way. This is an interesting insight and might be a suitable option to address the needs of open-minded, elderly people that like to use new technology but need special ways of interacting with it. Gamification for the elderly therefore seems to be a promising avenue for further research.

“DA Advocates” are the second cluster we identify who are also willing to use the system in principle if the features and price are right. The majority of these are men with a rather high willingness to pay. However, they have very specific ideas about the privacy features of a DA and therefore prefer to reject inferior solutions or refrain from buying at all. They like the idea of gamification, but do not need a complete serious game like the “Best Agers” prefer. An explanation about the data used seems to be necessary for both clusters.

Our study also contributes to different theoretical streams of research. First of all, it reveals that users are aware of privacy problems and even have some willingness-to-pay for an adequate privacy-enabling solution. This is in line with papers like Acquisti et al. (2016) and Mihale-Wilson et al. (2017), and our study shows that the standard privacy policy tends to be disliked by potential users. A prospective analysis that informs users about potential problems seems to the preferred solution, followed by a visual explanation. Users also seem to be very interested in the data basis used for decision-making. This is captured in the GDPR in the EU, which stipulates that data storage and usage should always be linked to clear, specific purposes. Most prospective users do not want detailed information about the underlying algorithm. This confirms the findings of previous research. Many users simply do not understand the underlying mathematics, and too much technical detail can put them off (Fischer and Petersen 2018). However, explainability in general and for assistant systems in particular seems to be an important issue, which lends support to the efforts made by the European Commission in their explainable and trustworthy AI initiative (European Commission 2019).

When it comes to the actual design of interfaces, we see that gamified elements or even a serious game can nudge users to engage with privacy settings. These preferences for gamification are very pronounced and show the potential of gamification. This finding supports work by, e.g. Liu et al. (2016) and Das et al. (2018). We even see that there is some additional willingness-to-pay for such a gamified user interface. The users in our study would be willing to pay an additional 5.10€ (23.8%) for a serious game interface. Digital assistant providers could use this insight to decide whether such a design option is suitable and profitable for them.

Implications for practice

Relevant information systems research also needs to be applicable in practice. Our research has managerial implications from the initial concept selection resulting in relevant design options to the user clusters.

The concept selection highlights three important feature attributes seen as relevant by prospective end-users. While initially based on a small sample, this relevance was later confirmed by our large-scale empirical survey. The three attributes are gamification of privacy behavior in DA, explainable artificial intelligence in DA, and the overall amount of privacy-relevant information displayed to users. Although these are based on current research trends, explainable AI and gamification are novel in the context of privacy for smart services. Some DA providers may want to find differentiation possibilities to address the upcoming privacy demands of their customers (Brill et al. 2019). We find that users generally opt for a restricted set of explanations, but maximum gamification of privacy in the context of digital assistants.

Our customer clustering further shows that this preference for maximum gamification is specific to “Best Agers”, who do not value digital assistants as much. “DA Advocates” generally prefer restricted gamification – but also prefer this to no gamification. Strong use of gamification therefore seems appropriate when introducing digital assistants to older users who might not use them otherwise. This might be especially true in scenarios such as ambient assisted living. Based on our findings, we encourage providers of such services to leverage gamification to improve their customers’ interaction with digital assistants and other smart services. This finding also puts the initial ranking across all users into perspective: For mainstream assistants, selective gamification may be the best option rather than a full-on serious game. In order to cater to both user clusters, a serious game could be offered independently, with an entry point in the assistant to gamified privacy functionality.

Further analysis of how these clusters differ may also lead to a more differentiated view of end-users’ privacy concerns about assistant systems (Knote et al. 2019). These concerns have been shown to be very relevant to users’ potential willingness to pay and adoption of DA in various scenarios (Brill et al. 2019; Mihale-Wilson et al. 2017; Zibuschka et al. 2019).

Our findings show that at least restricted privacy gamification and explainability of the underlying artificial intelligence are worth pursuing, as they have business relevance and can significantly increase users’ willingness to pay for digital assistants. This finding might well translate into other smart services, e.g. on the Internet of Things, as well. This suggests the need for further research and development in these areas, as it is far from clear how these features can be realized in practice.

Limitations

Although we tried to ensure a high quality of our user study, there are some limitations to our work. First, our literature review does not claim to be mutually exclusive or collectively exhaustive and might omit discussions, e.g. about cultural embedded privacy concerns even within the same legal framework. This may influence the key attributes. This also applies to the final set of key attributes selected by the expert panel. An end-user perspective of features is not included in the study refinement stage. However, the final results represent end-users’ views and preferences. Our findings suggest a specific version of privacy features, but we did not survey how developers should design such a serious game. Biased estimation is a common criticism when estimating WTP in a CBC analysis. Additionally, a too complex CBC survey could lead users to pursue simplification strategies. Even a small number of extreme values can result in under- or overestimated WTP values (Gensler et al. 2012). We addressed this potential bias by excluding all extreme values from our analysis. Further, our user sample is representative for prospective German users only. Given the fact that the digital assistant market is a global one, this is another limitation, as different cultures experience privacy differently (Acquisti et al. 2015; Rho et al. 2018).

Conclusions and outlook

A common feature of all digital assistants is their heavy reliance on personal data to actively support their users (Maedche et al. 2019). However, manufacturers or criminals can misuse these data. Users are therefore concerned, because they do not know how their data are actually used and what risks are involved. Privacy control features in digital assistants can help to counter this problem.

We analyzed users’ preferences and their willingness to pay (WTP) for DAs with different designs of privacy features. Based on a literature review and expert discussions, we identified three promising key attributes of privacy features: (1) the amount of personal data that is shown to the user, (2) the explainability of the DA’s decision, and (3) the degree of gamification of the UI. We utilized a choice-based conjoint analysis to identify user preferences of feature combinations. In addition, we added a price to each combination to estimate the users’ WTP (Gensler et al. 2012). According to our findings, 43.6% (132) of our participants would never buy any privacy assistance features. Those who would buy (56.4%; 171) are young, concerned about privacy, and risk-seeking. Our results show that an assistant that explains its decisions with regard to the data basis, and offers information about the possible impacts of the data disclosure, while interacting with the user as a serious game is most preferred. Data should be visualized. Users are willing to pay 21.39 €/month for such a product. Further, our results clearly show that gamified elements are preferred, since a DA without any form of gamified interaction was only ranked thirteenth.

In summary, our study contributes to the existing literature by investigating user preferences for the design of privacy features that can be implemented in digital assistants. Its insights have value for both researchers and manufacturers. Further research should concentrate on the importance of gamified elements. Manufacturers can use the findings to develop commercially successful assistants.

Future research should explore cultural differences in the perception of privacy assistance to address the global DA market and changes in privacy perception over time. A prototype could help participants become more involved. This prototype could also investigate users’ preferences for how privacy-related data can be presented in a comprehensible way. Other possible future work could explore the realization of a prospective analysis and a gamified interface.

Notes

German survey available at: https://split.to/DAPrivacy, English translation available in the appendix.

References

Acquisti, A., John, L. K., & Loewenstein, G. (2013). What is privacy worth? The Journal of Legal Studies, 42, 249–274. https://doi.org/10.1086/671754 .

Acquisti, A., Brandimarte, L., & Loewenstein, G. (2015). Privacy and human behavior in the age of information. Science, 347(6221), 509–514.

Acquisti, A., Taylor, C. R., Wagman, L., & Taylor, C. (2016). The economics of privacy. Journal of Economic Literature, 54, 442–492. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.54.2.442 .

Acquisti, A., Sleeper, M., Wang, Y., Wilson, S., Adjerid, I., Balebako, R., et al. (2017). Nudges for privacy and security: Understanding and assisting users’ choices online. ACM Computing Surveys, 50, 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1145/3054926 .

Adjerid, I., Acquisti, A., Brandimarte, L., & Loewenstein, G. (2013). Sleights of privacy: Framing, disclosures, and the limits of transparency. In L. F. Cranor (Ed.), The ninth symposium, Newcastle, United Kingdom (pp. 1–10). New York, New York: ACM Press. https://doi.org/10.1145/2501604.2501613 .

Andrade, L., & Zorzo, S. (2019). Privacy everywhere: A mechanism for decision making and privacy assurance in IoT environments. AMCIS 2019 Proceedings.

Andrews, R. L., Ainslie, A., & Currim, I. S. (2002). An empirical comparison of Logit choice models with discrete versus continuous representations of heterogeneity. Journal of Marketing Research, 39, 479–487. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.39.4.479.19124 .

Aparicio, M., Oliveira, T., Bacao, F., & Painho, M. (2019). Gamification: A key determinant of massive open online course (MOOC) success. Information & Management, 56, 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2018.06.003 .

Bélanger, F., & Crossler, R. E. (2011). Privacy in the digital age: A review of information privacy research in information systems. MIS Quarterly, 35, 1017–1042. https://doi.org/10.2307/41409971 .

Biswas, B., & Mukhopadhyay, A. (2018). G-RAM framework for software risk assessment and mitigation strategies in organisations. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 31, 276–299. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-05-2017-0069 .

Blohm, I., & Leimeister, J. M. (2013). Gamification - design of IT-based enhancing services for motivational support and behavioral change. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 5, 275–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-013-0273-5 .

Bosua, R., Clark, K., Richardson, M., & Webb, J. (2017). Intelligent warning systems: ‘Nudges’ as a form of user control for internet of things data collection and use. In M. Poblet, P. Casanovas, & E. Plaza (Eds.), Proceedings IJCAI 2017 workshop: Linked democracy: Artificial intelligence for democratic innovation (20, pp . 86–98). Melbourne.

Brill, T. M., Munoz, L., & Miller, R. J. (2019). Siri, Alexa, and other digital assistants: A study of customer satisfaction with artificial intelligence applications. Journal of Marketing Management, 35, 1401–1436. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2019.1687571 .

Buder, F., Dieckmann, A., Manewitsch, V., Dietrich, H., Wiertz, C., Banerjee, A., et al. (2020). Adoption Rates for ContactTracing App Configurations in Germany. https://www.nim.org/sites/default/files/medien/359/dokumente/2020_nim_report_tracing_app_adoption_fin_0.pdf. Accessed 1 July 2020.

Bundeskartellamt. (2020). Sektoruntersuchung Smart-TVs. https://www.bundeskartellamt.de/SharedDocs/Publikation/DE/Sektoruntersuchungen/Sektoruntersuchung_SmartTVs_Bericht.pdf. Accessed 7 July 2020.

BVDW. (2019). Verbraucherumfrage zum Thema Datenschutz. https://de.statista.com/statistik/studie/id/63483/dokument/umfrage-zum-datenschutz-in-deutschland-2019/. Accessed 25 July 2019.

Carnegie Mellon University. (2017). Usable Privacy Policy Project. Carnegie Mellon University. https://usableprivacy.org/. Accessed 5 June 2020.

Chapman, C, N., Love, E., & Alford, J, L. (2008). Quantitative early-phase user research methods: Hard data for initial product design, Proceedings of the 41st Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 37. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2008.367 .

Chung, H., & Lee, S. (2018). Intelligent Virtual Assistant knows Your Life. http://arxiv.org/pdf/1803.00466v1. Accessed 15 Feb 2020.

Cisco. (2020). From Privacy to Profit: Achieving Positive Returns on Privacy Investments: Cisco Data Privacy Benchmark Study 2020. https://www.cisco.com/c/en_uk/products/security/security-reports/data-privacy-report-2020.html. Accessed 13 June 2020.

Cranor, L. F., Guduru, P., & Arjula, M. (2006). User interfaces for privacy agents. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 13, 135–178. https://doi.org/10.1145/1165734.1165735 .

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555 .

Crossler, R. E., & Bélanger, F. (2019). Why would I use location-protective settings on my smartphone? Motivating protective behaviors and the existence of the privacy knowledge–belief gap. Information Systems Research, 30, 995–1006. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2019.0846 .

Das, A., Degeling, M., Smullen, D., & Sadeh, N. (2018). Personalized privacy assistants for the internet of things: Providing users with notice and choice. IEEE Pervasive Computing, 17, 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1109/MPRV.2018.03367733 .

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13, 319. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008 .

Derikx, S., Reuver, M. d., & Kroesen, M. (2016). Can privacy concerns for insurance of connected cars be compensated? Electronic Markets, 26, 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-015-0211-0 .

Desarbo, W. S., Ramaswamy, V., & Cohen, S. H. (1995). Market segmentation with choice-based conjoint analysis. Marketing Letters, 6, 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00994929.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness. In A. Lugmayr, H. Franssila, C. Safran, & I. Hammouda (Eds.), The 15th international academic MindTrek conference, Tampere, Finland (pp. 9–15). ACM: New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1145/2181037.2181040.

Drakonakis, K., Ilia, P., Ioannidis, S., & Polakis, J. (2019). Please Forget Where I Was Last Summer: The Privacy Risks of Public Location (Meta)Data. http://arxiv.org/pdf/1901.00897v1. Accessed 19 Sept 2019

Easwara Moorthy, A., & Vu, K.-P. L. (2015). Privacy concerns for use of voice activated personal assistant in the public space. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 31, 307–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2014.986642.

Ebbers, F., & Brune, P. (2016). The authentication game - secure user authentication by Gamification? In S. Nurcan, P. Soffer, M. Bajec, & J. Eder (Eds.), Advanced information systems engineering. CAiSE 2016, (pp. 101–115, lecture notes in computer science, Vol. 9694). Cham: Springer.

Emami-Naeini, P., Bhagavatula, S., Habib, H., Degeling, M., Bauer, L., Cranor, L. F., et al. (2017). Privacy expectations and preferences in an IoT world. In Proceedings of SOUPS 2017 (pp. 399–412). Berkeley, CA: USENIX Association.

European Commission. (2019). Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI. Brussels. https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/dae/document.cfm?doc_id=60419. Accessed 17 June 2020.

European Parliament & Council. (2018). General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): Art. 12.

Federal Constitutional Court. (1983). Census Act (Volkszählungsurteil) from 12/15/1983.

Fischer, S., & Petersen, T. (2018). Was Deutschland über Algorithmen weiß und denkt: Ergebnisse einer repräsentativen Bevölkerungsumfrage. https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/de/publikationen/publikation/did/was-deutschland-ueber-algorithmen-weiss-und-denkt/. Accessed 6 February 2019.

Förster, M., Klier, M., Kluge, K., & Sigler, I. (2020). Evaluating explainable Artifical intelligence – What users really appreciate. ECIS 2020 Research Papers.

Friedewald, M., & Pohoryles, R, J. (2016). Privacy and Security in the Digital Age: Privacy in the Age of Super-Technologies : Taylor & Francis. London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315766645.

Fruchter, N., & Liccardi, I. (2018). Consumer attitudes towards privacy and security in home assistants. In R. Mandryk & M. Hancock (Eds.), Extended abstracts of the 2018 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (CHI EA ‘18), 4/21/2018–4/26/2018 (pp. 1–6). New York, NY: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3170427.3188448.

Galitz, W, O. (2007). The Essential Guide to User Interface Design: An Introduction to GUI Design Principles and Techniques (pp. 888): Wiley.

Gensler, S., Hinz, O., Skiera, B., & Theysohn, S. (2012). Willingness-to-pay estimation with choice-based conjoint analysis: Addressing extreme response behavior with individually adapted designs. European Journal of Operational Research, 219, 368–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2012.01.002.

GlobalWebIndex. (2019). The digital consumer trends to know: 2019. https://www.globalwebindex.com/reports/trends-19. Accessed 24 June 2020.

Gluck, J., Schaub, F., Friedman, A., Habib, H., Sadeh, N., Cranor, L. F., et al. (2016). How short is too short? Implications of length and framing on the effectiveness of privacy notices. In Proceedings of the twelfth USENIX conference on usable privacy and security (SOUPS ‘16) (pp. 321–340). Berkeley, CA: USENIX Association.

Goldfarb, A., & Tucker, C. (2012). Shifts in privacy concerns. American Economic Review, 102, 349–353. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.102.3.349.

Green, P. E., & Srinivasan, V. (1978). Conjoint analysis in consumer research: Issues and outlook. Journal of Consumer Research, 5, 103. https://doi.org/10.1086/208721.

Gunaratne, J., Zalmanson, L., & Nov, O. (2018). The persuasive power of algorithmic and Crowdsourced advice. Journal of Management Information Systems, 35, 1092–1120. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2018.1523534.

Hern, A. (2019). Apple contractors ‘regularly hear confidential details' on Siri recordings. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/jul/26/apple-contractors-regularly-hear-confidential-details-on-siri-recordings. Accessed 27 May 2020.

Hill, K. (2012). How Target Figured Out A Teen Girl Was Pregnant Before Her Father Did. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kashmirhill/2012/02/16/how-target-figured-out-a-teen-girl-was-pregnant-before-her-father-did. Accessed 8 June 2020.

Hoy, M. B. (2018). Alexa, Siri, Cortana, and more: An introduction to voice assistants. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 37, 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2018.1404391.

Hui, T., Lee, S., & Teo, H. (2007). The value of privacy assurance: An exploratory field experiment. MIS Quarterly, 31, 19–33. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148779.

Huotari, K., & Hamari, J. (2017). A definition for gamification: Anchoring gamification in the service marketing literature. Electronic Markets, 27, 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-015-0212-z.

Jackson, D. N. (1976). Jackson personality inventory manual. Port Huron: Research Psychologists Press.

Jann, O., & Schottmüller, C. (2020). An informational theory of privacy. The Economic Journal, 130, 93–124. https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/uez045.

Johnson, R, M., & Orme, B, K. (1996). How many questions should you ask in choice-based conjoint studies. In (pp. 1–23). Beaver Creek: ART Forum.

Karniouchina, E. V., Moore, W. L., van der Rhee, B., & Verma, R. (2009). Issues in the use of ratings-based versus choice-based conjoint analysis in operations management research. European Journal of Operational Research, 197, 340–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2008.05.029 .

Kehr, F., Kowatsch, T., Wentzel, D., & Fleisch, E. (2015). Blissfully ignorant: The effects of general privacy concerns, general institutional trust, and affect in the privacy calculus. Information Systems Journal, 25, 607–635. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12062.

Ketchen, D. J., & Shook, C. L. (1996). The application of cluster analysis in strategic management research: An analysis and critique. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 441–458. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199606)17:6%3C441:AID-SMJ819%3E3.0.CO;2-G.

Knote, R., Janson, A., Söllner, M., & Leimeister, J, M. (2019). Classifying smart personal assistants: An empirical cluster analysis. In Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS). Maui, Hawaii, USA.

Krasnova, H., Hildebrand, T., & Günther, O. (2009). Investigating the value of privacy on online social networks: Conjoint analysis. ICIS 2009 Proceedings. https://doi.org/10.7892/BORIS.47455.

Kuehl, N., Lobana, J., & Meske, C. (2020). Do you comply with AI? — Personalized explanations of learning algorithms and their impact on employees' compliance behavior. ICIS 2019 Proceedings.

Kumar, S., Kumar, P., & Bhasker, B. (2018). Interplay between trust, information privacy concerns and behavioural intention of users on online social networks. Behaviour & Information Technology, 37, 622–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2018.1470671.

Lin, J., Sadeh, N., Amini, S., Lindqvist, J., Hong, J. I., & Zhang, J. (2012). Expectation and purpose: Understanding users’ mental models of Mobile app privacy through crowdsourcing. In A. K. Dey (Ed.), In proceedings of the 2012 ACM conference on ubiquitous computing (UbiComp ‘12) (pp. 501–510). New York, NY: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2370216.2370290.

Liu, B., Andersen, M. S., Schaub, F., Almuhimedi, H., Zhang, S., Sadeh, N., et al. (2016). Follow my recommendations: A personalized privacy assistant for Mobile app permissions. In Proceedings of the twelfth USENIX conference on usable privacy and security (SOUPS ‘16) (pp. 27–41). Berkeley, CA: USENIX Association.

Liu, X., Golab, L., Golab, W., Ilyas, I. F., & Jin, S. (2017). Smart meter data analytics. ACM Transactions on Database Systems, 42, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1145/3004295.

Lopez, J., Rios, R., Bao, F., & Wang, G. (2017). Evolving privacy: From sensors to the internet of things. Future Generation Computer Systems, 75, 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2017.04.045.

Maedche, A., Legner, C., Benlian, A., Berger, B., Gimpel, H., Hess, T., Hinz, O., Morana, S., & Söllner, M. (2019). AI-based digital assistants. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 61, 535–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-019-00600-8.

Manikonda, L., Deotale, A., & Kambhampati, S. (2018). What's up with privacy?: User preferences and privacy concerns in intelligent personal assistants. In J. Furman (Ed.), Proceedings of the 2018 AAAI/ACM conference on AI, Ethics, and society (AIES ‘18) (pp. 229–235). New York NY: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3278721.3278773.

McLean, G., & Osei-Frimpong, K. (2019). Hey Alexa … examine the variables influencing the use of artificial intelligent in-home voice assistants. Computers in Human Behavior, 99, 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.05.009.

Menard, P., & Bott, G. (2018). Investigating privacy concerns of internet of things (IoT) users. AMCIS 2018 Proceedings.

Meuter, M. L., Bitner, M. J., Ostrom, A. L., & Brown, S. W. (2005). Choosing among alternative service delivery modes: An investigation of customer trial of self-service technologies. Journal of Marketing, 69, 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.69.2.61.60759.

Mihale-Wilson, C., Zibuschka, J., & Hinz, O. (2017). About user preferences and willingness to pay for a secure and privacy protective ubiquitous personal assistant. In Proceedings of the 25th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), Guimarães, Portugal (pp. 32–47).

Mihale-Wilson, A. C., Zibuschka, J., & Hinz, O. (2019). User preferences and willingness to pay for in-vehicle assistance. Electronic Markets, 29, 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-019-00330-5.

Miller, K. M., Hofstetter, R., Krohmer, H., & Zhang, Z. J. (2011). How should consumers’ willingness to pay be measured? An empirical comparison of state-of-the-art approaches. Journal of Marketing Research, 48, 172–184. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.48.1.172.

Miller, T., Mittelstadt, B., Russell, C., & Wachter, S. (2019). Explanation in artificial intelligence: Insights from the social sciences. In Proceedings of the conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency (pp. 1–66). New York NY: ACM.

Moorthy, S., Ratchford, B. T., & Talukdar, D. (1997). Consumer information search revisited: Theory and empirical analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 23, 263. https://doi.org/10.1086/209482.

Naous, D., & Legner, C. (2019). Understanding users’ preferences for privacy and security features – A conjoint analysis of cloud storage services. In W. Abramowicz & R. Corchuelo (pp. 352–365). Seville, Spain: Springer international publishing.

Ogg, E. (2011). Zynga makes privacy a game with PrivacyVille. https://www.cnet.com/news/zynga-makes-privacy-a-game-with-privacyville/. Accessed 15 February 2020.

Pappachan, P., Degeling, M., Yus, R., Das, A., Bhagavatula, S., Melicher, W., et al. (2017). Towards privacy-aware smart buildings: Capturing, communicating, and enforcing privacy policies and preferences. In A. Musaev (Ed.), IEEE 37th international conference on distributed computing systems workshops (ICDCSW) (pp. 193–198). Atlanta, GA: IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDCSW.2017.52.

Pasquale, F. (2015). The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms That Control Money and Information. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rho, E. H. R., Kobsa, A., & Nguyen, C. (2018). In P. M. Bednar, U. Frank, & K. Kautz (Eds.), Differences in Online Privacy & Security Attitudes based on economic living standards: A global study of 24 countries (p. 95). Portsmouth, UK: ECIS 2018.

Ribeiro, M. T., Singh, S., & Guestrin, C. (2016). Why should I trust you? In B. Krishnapuram, M. Shah, A. Smola, C. Aggarwal, D. Shen, & R. Rastogi (Eds.), KDD '16: The 22nd ACM SIGKDD, San Francisco California USA (pp. 1135–1144). New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery Inc. (ACM). https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939778.

Roßnagel, H., Zibuschka, J., Hinz, O., & Muntermann, J. (2014). Users' willingness to pay for web identity management systems. European Journal of Information Systems, 23, 36–50. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2013.33.

Saffarizadeh, K., Boodraj, M., & Alashoor, T. (2017). Conversational assistants: Investigating privacy concerns, trust, and self-disclosure. Seoul, South Korea: ICIS 2017 Proceedings.

Schlereth, C., & Skiera, B. (2009). Schätzung von Zahlungsbereitschaftsintervallen mit der Choice-Based Conjoint-Analyse. Schmalenbachs Z betriebswirtsch Forsch, 61, 838–856. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03373670.

Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., & King, J. (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99, 323–338. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338.

Serenko, A., & Turel, O. (2007). Are MIS research instruments sSuppl?: An exploratory reconsideration of the computer playfulness scale. Information & Management, 44, 657–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2007.08.002.

Smith, H. J., Dinev, T., & Xu, H. (2011). Information privacy research: An interdisciplinary review. MIS Quarterly, 35(4), 989–1016.

Soumelidou, A., & Tsohou, A. (2020). Effects of privacy policy visualization on users’ information privacy awareness level. Information Technology & People, 33, 502–534. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-08-2017-0241.

Statista. (2019). Internetnutzer in Deutschland: Dossier. https://de.statista.com/statistik/studie/id/58515/dokument/internetnutzer/. Accessed 5 September 2019.

Steenkamp, J.-B. E. M., & Gielens, K. (2003). Consumer and market drivers of the trial probability of new consumer packaged goods. Journal of Consumer Research, 30, 368–384. https://doi.org/10.1086/378615.

Sutanto, J., Palme, E., Tan, C.-H., & Phang, C. W. (2013). Addressing the personalization-privacy paradox: An empirical assessment from a field experiment on smartphone users. MIS Quarterly, 37, 1141–1164. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.4.07.

Taylor, H. (2003). Most people are “privacy pragmatists” who, while concerned about privacy, will sometimes trade it off for other benefits. The Harris Poll. Harris Interactive.

Wedel, M., & Kamakura, W. A. (2000). Market segmentation: Conceptual and methodological foundations. Boston, MA: Springer.

Westin, A. F. (1967). Privacy and freedom. London: Bodley head.

Wu, D., Moody, G. D., Zhang, J., & Lowry, P. B. (2020). Effects of the design of mobile security notifications and mobile app usability on users’ security perceptions and continued use intention. Information & Management., 57, 103235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2019.103235.

Zibuschka, J., Nofer, M., & Hinz, O. (2016). Zahlungsbereitschaft für Datenschutzfunktionen intelligenter Assistenten. In V. Nissen, D. Stelzer, S. Straßburger, & D. Fischer (Eds.) (pp. 1391–1402). Ilmenau: Universitätsverlag Ilmenau.

Zibuschka, J., Nofer, M., Zimmermann, C., & Hinz, O. (2019). Users’ preferences concerning privacy properties of assistant systems on the internet of things. AMCIS 2019 Proceedings.

Availability of data and material

added to this submission, publish as online appendix.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Frank Ebbers’ work was partly funded by the German Ministry of Education and Research within the project ‘Forum Privacy and Self-determined Life in the Digital World’, https://www.forum-privatheit.de/.

Jan Zibuschka‘s work was partly funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy in the projects ENTOURAGE (Smart Services Worlds Innovation Competition) and ForeSight (Artificial Intelligence Innovation Competition).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest/competing interests

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Robert Harmon

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ebbers, F., Zibuschka, J., Zimmermann, C. et al. User preferences for privacy features in digital assistants. Electron Markets 31, 411–426 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-020-00447-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-020-00447-y