Abstract

Acknowledging the impact on their sales, companies strive to increase the number of positive online reviews of their products. A recently popular practice for stimulating online reviews is offering monetary rewards to customers in return for writing an online review. However, it is unclear whether such practices succeed in fulfilling two main objectives, namely, increasing the number and the valence of online reviews. With one pilot and two experimental studies, this research shows that offering incentives indeed increases the likelihood of review writing. However, the effect on review valence is mixed, due to contradictory psychological effects: Incentive recipients intend to reciprocate by writing favorable reviews but also perceive a need to resist marketers’ influence, which negatively affects their review valence. Finally, recipients who are less satisfied with the product are particularly prone to psychological costs and decrease the positivity of their online reviews. Consequently, incentives should be applied carefully.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Online product reviews are fast outpacing other sources of pre-purchase information, with roughly eight in ten U.S. consumers (82%) consulting online ratings and reviews before buying a product for the first time, and nearly half of them asserting that customer reviews help “a lot” to make them feel confident about their purchases (46%) (Pew Research Center 2016). In turn, online reviews—defined as “peer-generated product evaluations posted on company or third party websites” (Mudambi and Schuff 2010, p. 186)—have evolved into powerful determinants of companies’ financial success (e.g., Chevalier and Mayzlin 2006; Dhar and Chang 2009). In addition to their direct influence on sales (e.g., Babić Rosario et al. 2016, Cheung and Thadani 2012), online reviews also have an indirect impact on the success of a company, for example due to their potential to reduce product returns (Sahoo et al. 2018) or enable review-driven dynamic pricing strategies (Feng et al. 2019).

In particular, the number of online reviews and the representation of customers’ positive or negative evaluation within a review—the review’s valence (Gu et al. 2012)—drive sales performance. For example, customers’ awareness of a recently launched movie increases with the number of online reviews, which then increase revenues (Dellarocas et al. 2007; Liu 2006). Review valence is often indicated as a star rating in online settings. For restaurants, a rating increase of one additional star on a one-to-five review scale resulted in 5 to 9% sales increases (Luca 2016); for e-book readers, such improvement in ratings increased willingness to pay by 48.96 Euros (Kostyra et al. 2016).

Accordingly, companies seek to manage the online reviews for their products effectively, typically to increase the quantity and improve the valence of online reviews. In practice, manufacturers and service providers have adopted reward strategies to increase user-generated content online (Poch and Martin 2015) and experiment with incentive offers for online reviews. Adidas, for example, promises customers a voucher for a 15% rebate on their next purchase if they write an online review about any Adidas product. Companies in different service industries, from amusement parks to online job forums, also provide incentives to increase the number of online reviews (Streitfeld 2012), such as when restaurants offer coupons for free drinks in exchange for a posted review. These rewards are paid after the review is posted online. Companies may not require that the review must be favorable as, under 15 U.S. Code § 45, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) specifies that, among others, legal testimonials must be made by a real customer or user of the product or service and based on their real experience, must be an accurate description of expected or normal results, and may not be influenced by money, gifts, or publicity unless this is clearly disclosed. Thus, we define incentives for writing online reviews explicitly as monetary rewards that a company offers to customers solely in return for writing an online review, after they have bought the product or service. Our focus on monetary incentives as a predominant form of compensation in marketing practice sets us apart from studies that investigate free product samples as incentives given to registered customers to stimulate reviews (Wu 2019), or the provision of incentives by a retailer or platform operator (Khern-am-nuai et al. 2018).

In an offline environment, the effects of incentives for referrals are well established (e.g., Biyalogorsky et al. 2001; Jin and Huang 2014; Ryu and Feick 2007). However, offering incentives for online reviews is different from traditional referral reward programs in several respects. Notably, referrals typically occur between friends or acquaintances, so they induce specific social costs. In particular, the referrer risks losing a friend if the referral is fake or not in the recipient’s best interest (Wirtz et al. 2012). In addition, customers who are satisfied with the product or service should be more likely to refer it successfully to others through traditional word-of-mouth or customer referral efforts (e.g., Keiningham et al. 2018), because social costs prohibit customers from giving referrals for offerings that left them dissatisfied, and recipients are unlikely to purchase a product or service that evokes negative referrals. The payment of an incentive in these traditional referral programs also requires the acquisition of a new customer, so they stimulate positive product evaluations (Garnefeld et al. 2013; Schmitt et al. 2011). In contrast, incentivizing online reviews does not guarantee positive reviews or that only satisfied customers post reviews. The incentive payment does not require the actual acquisition of a new customer, and review authors and readers do not know each other, so social costs are less relevant. In summary, marketers cannot easily predict the effects of incentives on the number or valence of online reviews by extending prior referral research.

This study addresses people’s tendency to compare the benefits and costs of accepting an incentive as compensation for writing an online review. We anticipate two, potentially contrasting psychological effects on this perceived cost–benefit ratio. On the one hand, customers might value the reward offer and feel compelled to reciprocate by writing a (favorable) online review. On the other hand, customers recognize the company’s persuasive attempt, increasing psychological costs and motivating attempts to appear unbiased, which may inhibit (favorable) online reviews. Against this conceptual backdrop, the current study poses three research questions. First, do monetary incentive offers raise the likelihood that customers write online reviews, that is, the number of online reviews? Second, does offering incentives increase review positivity and thus positively influence the valence of online reviews? Third, does customers’ product satisfaction affect their reactions to incentive offers for online reviews? To address these questions, we first conducted a pilot study to test whether these conceptually derived psychological mechanisms actually emerge in response to a monetary incentive for online review writing. Then in Study 2, we investigate participants’ real experiences, and in Study 3, we use a fictitious setting to test the psychological effects of incentive offers on online review writing.

In turn, this research makes three major contributions. First, we confirm that monetary incentives increase the number of online reviews. Considering the practical relevance of online reviews for companies, research on how to influence customers’ online review publication likelihood is important. Past studies in marketing and information system research have identified characteristics of product (Berger and Iyengar 2013; Lovett et al. 2013; Moldovan et al. 2011), situation (Dellarocas et al. 2010; Eisingerich et al. 2015; Moe and Schweidel 2012), and sender (Eelen et al. 2017; Mathwick and Mosteller 2016; Thakur 2018) that influence online review writing, but proactive marketing strategies to manage online reviews have rarely been studied. We empirically demonstrate that offering incentives has the potential to more than double customers’ review publication likelihood (based on increases of 124% and 147% established in Studies 2 and 3, respectively).

Second, we contribute to the theoretical understanding of psychological mechanisms that determine consumers’ responses to incentive offers within the emerging digital sector, in particular with regard to the customer–manufacturer online interaction. Based on social exchange theory, we present positive reciprocity as a relevant factor in consumer decision making which has received scant attention in both marketing and information system research. In addition, we highlight psychological costs triggered by customers’ motivation to resist (perceived) manipulative attempts, a factor not previously studied in the context of online review writing. We show that incentives do not necessarily increase online review valence, as reciprocity and resistance to persuasion emerge as conflicting, underlying psychological mechanisms. The benefits associated with reciprocity toward the company can enhance the valence of published online reviews, but the psychological costs associated with resisting persuasion cancel out this positive effect. Therefore, companies should carefully consider using incentives to influence customers’ online review writing. They increase the likelihood that people write reviews, but they do not determine the valence of those reviews, risking the proliferation of negative reviews. Illuminating these unintended effects of customer incentives represents an important contribution to marketing research and practice.

Third, we identify a moderating effect of product satisfaction on the relationship between incentive offers and the resulting psychological costs. Less satisfied customers react more negatively to an incentive offer, compared with more satisfied customers. Companies accordingly should evaluate carefully to which products or services they want to apply incentive offers.

Theoretical background

Social exchange theory

Originating in sociology, social exchange theory (Blau 1964) seeks to explain the emergence of social interactions, assuming that social behavior typically is motivated by the rewards that individuals anticipate from the interaction. Rewards may be goods or services or other tangible or intangible benefits that satisfy an individual’s needs or goals. Additional basic assumptions of social exchange theory are that individuals strive to maximize rewards and minimize losses or punishments, and that social exchange is necessary because others control valuables or necessities and are therefore in a position to reward an individual, who in order to induce the other to reward them, has to provide rewards in return. Summarizing, social interaction is viewed as “an exchange of mutually rewarding activities in which the receipt of a needed valuable (good or service) is contingent on the supply of a favor in return” (Burns, 1973, p. 189).

In general, exchange relationships are motivated by personal self-interest (Mills and Clark 1982). Because parties must expend valuable economic and social resources to participate in social exchanges, which reduces the overall benefit of the exchange, parties remain in the relationship only as long as the rewards outweigh the costs (Homans 1958). Therefore, the social behavior of an individual can be explained by the net benefit they anticipate or gained from the exchange (Lambe et al. 2001; Meeker 1971). The types of resources exchanged in social relationships often get classified into two forms: economic and socioemotional (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005). Economic outcomes address financial needs and tend to be tangible; socioemotional outcomes address exchange partners’ social and psychological needs. According to Blau (1964), benefits that do not have any clear material value, such as social approval and respect, tend to be particularly important in motivating social exchange (e.g. Cheung and Lee 2012, Shi and Liao 2017). Social exchange theory has been discussed in recent literature on online reviews to explain customer motivations to provide information on online platforms (Belanche et al. 2019; Chang and Hsiao 2013; Cheung and Lee 2012), however, applying it to the online exchange context between customer and manufacturer offers a novel perspective.

Effects on review writing likelihood

Offering a reward for writing an online review can initiate a social exchange if the customer perceives a net benefit after comparing the value of the incentive against the costs of performing the action, such as time, effort, or opportunity costs (Berger 2014). Generally, incentivizing a previously unrewarded activity is likely to increase the benefit of the action. Companies typically have not rewarded people for writing online reviews, so customers might appreciate the incentive offer as an unexpected benefit. By writing a review, customers strive to re-establish a balanced relationship with the company. Consequently, and in line with social exchange theory, we posit that offering an incentive has a direct positive effect on online review writing likelihood.

Beyond the economic outcome, customers consider psychological outcomes. In the case of rewarded online reviews, such outcomes might include psychological benefits attributable to reciprocity gains and the psychological costs associated with resisting marketer influences. Specifically, writing an online review can produce psychological benefits for the author, such as establishing a status as an expert (Lampel and Bhalla 2007) or reducing post-purchase dissonance (Berger 2014). The additional offer of an incentive likely elicits expectations of reciprocity, which is a basic tenant of social exchange theory suggesting that social relations are contingent on mutually rewarding activities (Blau 1964; Burns 1973), and generally dictate that if one party supplies a benefit, the receiving party should respond in kind (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005). Reciprocity is a dual concept, such that positive reciprocity is an intention to reward those who have been kind, whereas negative reciprocity implies punishing those who have been unkind. Both decisions, reward and punishment, may reduce a person’s payoff in an exchange relationship, due to the time and effort involved (Caliendo et al. 2012). However, in psychological terms, positive reciprocation should lead to positive payoffs, because people usually feel good about doing “the right thing” by returning a favor (Burger et al. 2009). Empirical evidence confirms that people tend to be positively reciprocal in their actions (Dohmen et al. 2008). Thus, customers may achieve a psychological reward from writing an online review because they feel good about giving back to the company, and we anticipate an indirect positive effect of the incentive offer on review writing likelihood, due to such reciprocity gains.

Incentives might also influence review writing likelihood negatively, for example if they raise the psychological costs associated with the need to cope with persuasive attempts by marketers. Unlike other marketing contexts in which customer incentives are applied, such as coupons or loyalty cards, online review writing benefits (anonymous) other customers. It represents a voluntary contribution to a public good and thus a form of prosocial customer behavior (Gneezy et al. 2011), as also illustrated by the research interest in review helpfulness (e.g., Lee and Choeh 2016). Not only may offering a positive incentive shift the review writing decision from social to monetary (Gneezy et al. 2011), it may also break social norms of trust as the explicit incentive can signal a marketer’s attempt to manipulate prosocial customer behavior. Many people do not wish to be influenced and are motivated to resist persuasion (Ringold 2002). Persuasive attempts, such as being offered an incentive for writing an online review, that seemingly impose a certain behavior or opinion on the customer could trigger motivated resistance (Fransen et al. 2015). For example, persuasive attempts that push people into choices that seem to benefit the communicator rather than the recipient may make the latter suspicious of the ulterior motives of the former (Koslow 2000). Potential review writers may weigh whether the company benefits more from an online review than they would. In the context of prosocial acts, monetary incentives can dilute the signal to oneself of having made a voluntary contribution (Gneezy et al. 2011). Thus, customers might consider if agreeing to write a review will create a sense, for themselves or others, that they have been “bought” by the company, triggering resistance. In summary, we expect that targeted customers include both psychological costs and gains in their cost–benefit calculation when deciding whether to write an online review, and we hypothesize:

-

H1: The effect of offering an incentive to write an online review on online review likelihood is partially mediated by (a) reciprocity gains and (b) psychological costs.

Effects on review valence

The effect of incentives on online review valence also may depend on the described psychological mechanisms. On the one hand, incentives may lead to more favorable online reviews, due to increased perceived reciprocity gains. As noted, customers experience benefits from positive reciprocity, because paying back a favor enables them to regain a balanced relationship with the company. To reciprocate, customers need to support the company’s business, which requires positive reviews. Thus, the valence of online reviews may improve when incentives are offered.

On the other hand, the psychological costs associated with accepting an incentive offer might negatively influence review valence. For example, customers may believe that, in possible violation of the social norm that online reviews reflect a review writer’s honest opinion and experiences, the company expects a more favorable review in return for the incentive. Motivated resistance entails a state in which people aim to bolster their current attitude by generating thoughts that support their prior attitudes (e.g., Abelson 1959; Lydon et al. 1988). To avoid feeling manipulated and establish, for themselves and others, that they are unbiased in their views and, despite the extrinsic incentive, still perform a voluntary behavior (Gneezy et al. 2011), customers might accept the incentive but counterbalance the perceived influence by writing an online review that critically assesses the product or service, leading to more negative review valence.

-

H2: The effect of offering an incentive to write an online review on online review valence is mediated by (a) reciprocity gains and (b) psychological costs.

The role of customer satisfaction

Customer satisfaction is typically defined as the outcome of an evaluative process that contrasts pre-purchase expectations with perceptions of performance during and after the consumption experience (Oliver 1980). Satisfaction is an important variable for marketing research and practice as it has a positive effect on firm performance (Fornell et al. 2016). It is equally important for repeat business as it is for new customer acquisition because satisfaction strongly influences customer loyalty (Kumar et al. 2013) as well as word-of-mouth behavior (Anderson 1998; Mende et al. 2015; von Wangenheim and Bayón 2007).

In general, less satisfied customers provide less favorable online reviews than do highly satisfied customers, indicating that satisfaction could influence the relationships of incentive offers with online review writing likelihood and valence. As dissatisfied customers will typically write negative online reviews, motivating them to do so with incentives seems to be of low practical relevance. Hence, we focus on satisfied and moderately satisfied customers in our theoretical and empirical analysis. In particular, we expect attenuating effects of incentives for moderately satisfied customers, for whom the incentive offer especially increases psychological costs, because they may be more likely to perceive the incentive offer as a bribe the company uses to attain (unjustified) positive reviews. Compared with customers who do not receive an incentive offer, they should write less favorably about the product or service. In contrast, the presence of a reward for writing a review should not change highly satisfied customers’ general inclination to write positively about the product or service. For them, the psychological costs (i.e., need to counterbalance perceived influence) remain low when an incentive is offered. We hypothesize:

-

H3: The negative effect of the incentive offer on review valence via psychological costs is moderated by satisfaction, such that the effect of an incentive offer on customers’ experienced psychological costs is stronger for moderately satisfied than for highly satisfied customers.

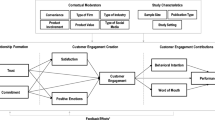

The conceptual model in Fig. 1 depicts these hypothesized psychological consequences and the suggested behavioral consequences of incentivizing review writing. We test these predictions in a pilot study and two experimental studies (see Table 1 for an overview). To assess the conceptually derived relevance of customers’ positive and negative reactions to an incentive offer, we first conduct a survey with open-ended questions in our Study 1 (McGrath et al. 1993). Then, to test the theoretically derived relationships empirically, we conduct two experimental studies. Study 2 analyzes the main effect of incentive offers on review likelihood and valence, as well as the indirect effects through psychological gains and costs; Study 3 additionally incorporates the moderating effect of satisfaction. Across our three studies, we used data from two sources–a consumer panel (MTurk, Study 1 and 2) and students (Study 3)–and employed a multi-method approach by conducting a survey with open ended questions (Study 1) and two experimental studies (Studies 2 and 3), set in different product contexts. This approach serves to establish the validity and generalizability of our results across different types of respondents, settings and methods. In addition, this approach addresses limitations specific to each data source and technique. For example, by replicating the student sample results with respondents from Mturk, we limit the potential lack of external validity attached to student samples (Kees et al. 2017).

Study 1: Pilot study

Study 1 provides a “reality check” of the theoretically derived psychological mechanisms. We investigate customers’ first impressions and behavioral responses to incentives for writing online reviews by conducting a survey with open-ended questions.

Method

We recruited customers from the online Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) platform (He and Bond 2015). To qualify to participate, the MTurk members had to have bought a product online on Amazon.com within the last three months. We obtained a sample of 100 paid U.S. respondents with a mean age of 38 years, 48% of whom were women. If these customers purchased more than one item, they were asked to pick a particular one on which to base their answers. The products mentioned by the respondents covered a variety of product categories, such as clothing, beauty products, and technical equipment.

In developing the survey, we relied on a counterfactual thinking approach (Bagozzi et al. 2016; Yang et al. 2016). Questions based on this approach ask participants to imagine what their thoughts and feelings would have been, had an event in the past occurred slightly differently (Roese 1997; Roese and Olson 1995). Thus, they envision alternatives to the experienced event (Mandel and Lehman, 1996). In our survey, participants had to complete seven sentences, after they recalled the situation when the focal ordered product had been delivered. In the next step, we asked them to imagine that, when they opened the package, they found a notecard next to the product. A mock-up of this notecard appeared in the survey; it asked them to post an online review on the fictitious review page “productreview.com” in exchange for a $10 Amazon gift card (see Appendix 1 for more details on the questionnaire). The counterfactual thinking approach presented a more realistic alternative to traditional scenario approaches in that it allowed subjects to mentally simulate alternatives to an experienced event (Byrne and McEleney 2000; Mandel et al. 2005; Roese 1997; Roese and Olson 1995). Thus, this approach allowed us to present all participants with the same incentive situation.

Results

We relied on content analysis as an observational research technique (Kolbe and Burnett 1991) to structure the latent content systematically. We categorized the statements into positive attitudes leading to higher review likelihood or more positive valence and negative attitudes leading to lower review likelihood or more negative valence. In line with our theoretical argument, we find such opposing psychological influences on the tendency to write a (positive) review in response to a monetary incentive. Specifically, some participants described an increased likelihood to (positively) review, whereas others indicated they would refrain from writing a (positive) review. Respondents with an increased tendency to write a (positive) review articulated, for example:

[This is what I like about being offered an incentive for writing an online review:]

…It would cause me to write a review that I would not have done otherwise.

[If I found such a notecard in the product package and saw that there is an incentive offered for writing an online review, I would think…].

… I am definitely going to do this review and get the incentive.

[If I decided to write an online product review in response to such a notecard, I would feel…].

…very motivated to leave a positive review.

....great. I would try to write the best review possible.

…happy about writing something positive.

However, other respondent statements implied that the incentive offer would have kept them from writing a (positive) review:

[If I found such a notecard in the product package and saw that there is an incentive offered for writing an online review, I would think…].

… I wouldn’t write one because I want to give an honest opinion and not base it on getting anything in return.

… I would be hesitant to do it as it seems like the company is using the $10 to solicit reviews.

[If I decided to write an online product review in response to such a notecard, I would feel…].

…I would not do it. That is not how I operate, but I would definitely not do it for pay.

…to resist the influence to write a positive review and try to write a truthful review.

…pressured to write a positive review, but ethically bound to write an honest one, which may or may not be positive.

Study 2

To test the effects that incentive offers have on online review publication likelihood and online review valence, we next conducted two experimental studies. We relied on a scenario approach, as is commonly used in research on online reviews (e.g., Grewal and Stephen 2019; Schlosser 2005). This method asks participants to put themselves in hypothetical roles, which is well-suited to our study context for two main reasons. First, at this early stage of research into the effects of incentives on reviewing behavior, we emphasize the internal validity of our results. Second, we hope to uncover the psychological processes that drive customer responses to incentives (i.e., reciprocity gains and psychological costs), which would be difficult using behavioral customer data. Study 2 refers to a past real purchase situation to analyze participants’ psychological responses and behavioral intentions, had a monetary incentive been offered.

Research design and participants

To analyze the effects of incentives on online review publication likelihood and review valence, we used a posttest only control group design (Campbell and Stanley 1963), in which we manipulated the incentive (incentive offer versus no incentive offer) by exposing only the treatment group to a situation in which they were offered an incentive for writing an online review. The data were collected online. We used MTurk to recruit participants and obtained a sample of 191 paid U.S. respondents. To take part in the study, participants had to have bought a product online at Amazon.com within the three months preceding the study. Similar to Karmakar and Bollinger (2015), we conducted attention checks by integrating logical statements (Abbey and Meloy 2017), such as “The sun never shines on Mondays.” We excluded eight participants who failed the attention checks (Barone et al. 2017), leaving a final sample of 183 study participants with an average age of 37 years, 45% of whom were women. Respondents were randomly assigned to one of the two experimental groups.

Procedure

All participants provided information about a particular purchase (e.g., category, price, manufacturer), conducted online on Amazon.com. Next, they had to recall the situation when they received and opened the package that contained the ordered product. They were asked to imagine that they found a notecard in the package, requesting that they post an online review on the fictitious review website “productreviews.com.” Depending on their randomly assigned experimental group, the notecard differed. In the treatment group, it promised a $10 Amazon gift card in exchange for writing an online review; it did not specify that the review had to be positive. However, it stated that to receive the reward, customers had to email a link to their review to the manufacturer. The monetary value of the gift card was chosen based on a screening of real incentive offers for online reviews which we found online or on notecards accompanying product packages. The majority of the incentive offers were between $5 and $20 with a median of $10. Hence, $10 seemed to be a realistic offer. In the control group, the notecard asked participants to post an online review on the same fictitious review website but did not mention any incentive. After reading the scenario description, all participants rated their likelihood to write an online review and the likely valence of their review. They also completed items that measured reciprocity gains and perceived psychological costs. Finally, we checked the manipulations before gathering respondents’ demographic data.

Measures

We measured online review writing likelihood by asking “How likely is it that you will write an online review about this product?” on a percentage scale, ranging from 0% = “not at all likely” to 100% = “definitely.” We measured online review valence according to the overall rating of the product, ranging from 1 (“very poor”) to 5 (“very good”) stars (King et al. 2014), which is an established method to capture review valence (Ho-Dac et al. 2013; Sridhar and Srinivasan 2012). In addition, we measured reciprocity gains using items similar to those used by Thomson and Johnson (2006) and Hennig-Thurau et al. (2004). We developed a three-item scale to measure psychological costs on a 7-point Likert scale. See Table 2 for all items used to measure reciprocity gains and psychological costs.

Manipulation checks

The manipulation check, using a Likert scale, confirmed that only the treatment group reported learning about the incentive offer (t(181) = −16.05, p = 0.00, MIncentive = 6.05, SDIncentive = 1.96; MControl = 1.75, SDControl = 1.66), in support of the manipulation’s effectiveness.

Validity assessment

We conducted validity checks for reciprocity gains and psychological costs to assess their construct, convergent and discriminant validity. The factor loadings (> .86), factor reliability (> .89), and average variance extracted (AVE) (> .82) all exceeded the common thresholds, such that they exhibited convergent and discriminant validity (see Table 2).

Results

To test our hypotheses, we employed the PROCESS procedure, a computational tool for path analysis-based moderation and mediation analyses (Hayes 2013). With Model 4 of this procedure, we tested the direct effects of an incentive offer on online review writing likelihood and online review valence; we also assessed whether customers’ perceived reciprocity gains and psychological costs mediated these effects. We find a positive direct effect of the incentive offer on review likelihood (b = 31.4662, SE = 4.2056, 90% confidence interval (CI) = [24.5126, 38.4197]).Footnote 1 This effect in turn is partially mediated by reciprocity gains, in support of H1a (b = 6.8090, SE = 2.9294, 90% CI = [2.3368, 11.8130]). However, we cannot confirm H1b, in which we predicted that the effect of an incentive offer on publication likelihood would be partially mediated by psychological costs (b = −1.0878, SE = 1.2346, 90% CI = [−3.2799, 0.7280]). In line with our prediction, we do not find a significant direct effect of incentives on online review valence (b = 0.0547, SE = 0.1007, 90% CI = [−0.1117, 0.2211]). As hypothesized, reciprocity gains (b = 0.0401, SE = 0.0284, 90% CI = [0.0060, 0.0963]) and psychological costs (b = −0.0574, SE = 0.0297, 90% CI = [−0.1086, −0.0125]) both mediate the effects of monetary incentive offers on online review valence, confirming both H2a and H2b.

Discussion

Monetary incentive offers positively influence online review writing likelihood; the incentive directly increases the benefits of review writing. Positive reciprocity provides an additional benefit. However, the effect of incentives on review valence is ambiguous, as conceptually supported by the contradictory effects of reciprocity gains and psychological costs on online review valence, which also became apparent in our pilot study. Although incentives have a positive effect on review likelihood through reciprocity gains, they negatively influence online review valence through psychological costs, possibly because customers feel obligated to express more critical assessments of the product to counterbalance perceptions of “being bought.” The total effect of the incentive on online review valence is insignificant (b = 0.0374, SE = 0.0974, 90% CI = [−0.1236, 0.1984]), meaning that the effects cancel each other out.

Study 3

With Study 3, we seek to enhance the generalizability of the results by replicating our Study 2. We also extend the results by additionally taking different customer satisfaction levels into account.

Research design and participants

We employed a 2 × 2 between-subjects design to assess the effect of monetary incentive offers on review writing likelihood and valence. To introduce satisfaction as a contextual variable, we manipulated both the existence of an incentive (incentive offer vs. no incentive offer) and the level of customer satisfaction (high vs. moderate). We assume that offering incentives to dissatisfied customers is not in the best interest of marketers. While the incentive might increase dissatisfied customers’ review writing likelihood, the resulting reviews are likely unfavorable. To confirm our assumption, we conducted a pre-study (see Appendix 2 for a more detailed description of our pre-study) which showed that dissatisfied customers indeed accepted the incentive and were more likely to write an online review compared to a situation without any incentive offer. However, the incentivized online reviews did not differ from non-incentivized reviews in terms of valence. Thus, as the valence was low (1.9 stars on average in our pre-study) offering incentives to dissatisfied customers increases the number of unfavorable reviews, which is of no practical value for marketers, leading us to focus our Study 3 on highly and moderately satisfied customers.

Data were collected using a paper-and-pencil survey and a student sample. Student samples have long been popular in marketing research and are comparable in quality to other subject pools (Kees et al. 2017). We acknowledge that findings gathered from student samples are not always generalizable to non-student adults. However, in replicating the main results from Study 2 which employed a non-student sample, confidence in the external validity of results increases. In total, 168 undergraduate and graduate business students of a large German public university voluntarily took part in the study during class time and without receiving any incentive. Average age was 23 years, and 62% of the participants were women. Participants were randomly assigned to the experimental groups.

Procedure and measures

Similar to Study 2, all participants received a scenario description and questionnaire. The online purchase of a fitness DVD provided the experimental setting, such that participants had to imagine that they had purchased the fitness DVD Fit and Fun. It had been delivered, and they had already tested the product. The scenario description also contained information about typical attributes of a fitness DVD, manipulated to evoke different levels of satisfaction. Depending on the experimental group, participants read either that they were very satisfied or moderately satisfied with the DVD. For the incentive manipulation, only the treatment group read that they had received an incentive offer in return for writing an online review, with a notecard and description similar to the one in Study 2 (offer of a €10 Amazon gift card in return for writing an online review). However, unlike Study 2, the control, no-incentive group did not receive any notecard asking for an online review. This variation helps increase the generalizability of our findings and exclude alternative explanations based on the potential additional influence of any message from the company.

In the next step, participants responded to the same set of questions used in Study 2: They rated their intention to write an online review and the valence of that review, their perceived psychological costs, and the benefits of behaving reciprocally (see Table 3 for all items used to measure reciprocity gains and psychological costs). Finally, we again included manipulation checks and asked for participants’ demographic data.

Manipulation checks

Before testing the hypotheses, we confirmed that the participants in the treatment group recognized the incentive offer (t(156) = −12.35, p = 0.00, MIncentive = 5.80, SDIncentive = 1.74; MControl = 2.30, SDControl = 1.81). Satisfaction in the moderate satisfaction condition was lower than in the high satisfaction group (t(145,17) = −7.70, p = 0.00, Mmoderate_satisfaction = 4.31, SDmoderate_satisfaction = 1.47; Mhigh_satisfaction = 5.85, SDhigh_satisfaction = 1.02).

Validity assessment

We conducted validity checks for reciprocity gains and psychological costs to assess their convergent and discriminant validity. The factor loadings (> .86), factor reliability (> .90), and AVE (> .83) exceeded the common thresholds, indicating convergent and discriminant validity (Table 3).

Results

We tested the hypotheses by again employing the PROCESS procedure with Model 4 (Hayes 2013). We started by testing the direct effect of an incentive offer versus no incentive offer on online review publication likelihood. In support of H1, and in line with our results from Study 2, an incentive offer significantly and positively affects customers’ online review writing likelihood (b = 15.9610, SE = 4.1079, 90% CI = [9.1643, 22.7578]). This effect is partially mediated by reciprocity gains (b = 5.7304, SE = 2.2814, 90% CI = [2.1579, 9.6216]) (H1a). As in Study 2, the effect of an incentive offer on online review likelihood is not mediated by psychological costs (b = 3.6026, SE = 1.9481, 90% CI = [0.8366, 7.1844]) leading us to reject H1b. We identify a positive effect of the incentive offer on review valence through reciprocity gains (b = 0.0885, SE = 0.0480, 90% CI = [0.0225, 0.1779]), as suggested in H2a, and a negative effect through psychological costs (b = −0.1559, SE = 0.0659, 90% CI = [−0.2735, −0.0580]), in line with H2b.

Next, we tested the moderated mediation predicted in H3 using Model 7 in PROCESS (Hayes 2013). In line with our theoretical argument, we find a significant negative moderating effect of satisfaction on the effect of incentives on perceived psychological costs (b = −0.9375, SE = 0.5351, 90% CI = [−1.8228, −0.0522]). The confidence intervals of the indirect effects of the incentive offer on the online review valence mediated by the psychological costs indicate significant effects for moderately satisfied customers (b = −0.2130, SE = 0.0898, 90% CI = [−0.3785, −0.0857]) as well as for highly satisfied customers (b = −0.0974, SE = 0.0619, 90% CI = [−0.2049, −0.0073]). As shown in Fig. 2, the difference in psychological costs elicited by an incentive offer is greater among moderately satisfied than among highly satisfied customers. These moderately satisfied customers’ psychological costs are higher when an incentive is offered, compared with a situation with no incentive offer (t(60.48) = −5.14, p = 0.00, MIncentive = 3.44, SDIncentive = 1.86; MControl = 1.71, SDControl = 1.04). Highly satisfied customers also perceive higher psychological costs if an incentive is offered (t(67.85) = −1.86, p = 0.07, MIncentive = 3.03, SDIncentive = 2.19; MControl = 2.24, SDControl = 1.54). However, the presence of the incentive offer, relative to no incentive, has a clearly stronger effect on moderately satisfied customers than on highly satisfied customers. Finally, as expected, satisfaction does not influence the indirect effect between incentive offers and review valence through reciprocity gains (b = −0.0763, SE = 0.5171, 90% CI = [−0,9318, 0.7792]). That is, customers who are offered a monetary incentive experience the same level of reciprocity gains independent of their satisfaction.

Discussion

Study 3 enhances the internal validity of our findings by replicating the results of Study 2. To also achieve the goal of increased generalizability it is suggested for replication studies to collect “new data in additional … settings and contextual environments” (Block and Kuckertz 2018, p. 356). Hence, our study designs differed in five ways. (1) We used an Mturk vs. a student sample; (2) We employed an online versus a paper-and-pencil survey. (3) While in Study 2 customers were instructed to recall their last purchase on Amazon.com when answering the survey, Study 3 asked participants to consider a fictitious product. (4) The control group in Study 2 received a notecard which asked for writing an online review without offering an incentive, the control group in Study 3 received no notecard at all. (5) Finally, Study 3 included satisfaction as a context variable. Online review publication likelihood is positively influenced, both directly and indirectly through increased reciprocity gains, by the offer of an incentive. Review valence also is influenced positively through reciprocity gains and negatively through psychological costs. These two effects neutralize each other, as indicated by the insignificant total effect of the incentive offer on online review valence (b = 0.0210, SE = 0.1379, 90% CI = [−0.2070, 0.2491]). The effect of incentives on psychological costs also is stronger for moderately satisfied customers than for highly satisfied customers.

General discussion and implications

This research provides insights into how monetary incentive offers affect online review writing likelihood and valence. We have determined and tested two distinct psychological processes triggered by the incentive offer. Thus, we contribute to the further development of theory and literature by expanding the scope of social exchange theory, in particular considerations of reciprocity, within the emerging digital sector, and applying it to the customer–manufacturer interaction. As Cropanzano and Mitchell (2005) note, little is known about processes—as the authors call it, the “black box”—of social exchange. To gain insights into psychological mechanisms that are relevant to social exchanges in the context of incentivized online reviews, we conducted several studies. Initially, we explored and confirmed the existence of the theoretically derived contradicting effects by analyzing participants’ real experiences. Then in two experiments with different product contexts, we found evidence of positive reciprocity and negative resistance effects on online review writing likelihood. On the one hand, customers gain benefits through positive reciprocation after receiving an incentive offer. Psychology literature indicates that people typically exhibit moderate to strong positive reciprocity (Dohmen et al. 2008), yet this trait still has not received substantial attention in marketing research. On the other hand, an incentive offer may give rise to psychological costs if it triggers customers’ motivation to resist (perceived) manipulative attempts on behalf of the company. Illuminating this “dark side” of customer incentives represents an important contribution to marketing research. Customers’ desire to resist the perceived pressure to comply with marketers’ goals has been studied in advertising contexts (e.g., Kirmani and Zhu 2007), but research into its effects on online review writing is limited. Our research shows that psychological costs only exert impacts on review valence, not review writing likelihood, so monetary incentives can be effective, even for customers who are inclined to resist marketers’ influence. Apparently, many customers find an incentive appealing but then need to counterbalance the emerging psychological costs by affirming their incorruptibility by offering more negative reviews. Similar processes may take place for other marketer-provided incentives (e.g., referral campaigns, loyalty programs), or other customer prosocial behaviors.

The differential effects of incentive offers on online reviewing behavior also suggest several implications for marketing practice. First, incentives are a promising tool if the company’s goal is to increase the number of online reviews for its goods or services. Online reviews give a company immediate access to customers’ product evaluations (Park and Nicolau 2015), which is an important benefit. Irrespective of their valence, the sheer number of reviews also can facilitate customer decision making (Mudambi and Schuff 2010) and thus drive company sales (Babić Rosario et al. 2016). Our theoretical foundation and the results of our two experimental studies offer consistent evidence of direct and indirect positive effects of monetary incentives on review writing likelihood. The hypothesized negative effect, through psychological costs, is not supported, so these results encourage companies to offer incentives to stimulate review writing. The early phases of a product or service lifecycle might particularly benefit from such an incentive strategy, because both positive (Duan et al. 2008) and negative (Berger et al. 2010) reviews can increase customer awareness.

Second, because review valence cannot be managed, marketers need to be cautious and assess the possible drawbacks of an incentive strategy. The psychological benefits of incentives through reciprocity gains and the negative effects through psychological costs neutralize each other in terms of online review valence. Based on the results of our pre-study, we find that this also holds true for dissatisfied customers. Dissatisfied customers will more likely write an online review when an incentive is offered. However, the rating stays low. Consequently, managers should carefully consider if increasing the number of reviews but not necessarily improving their valence will be beneficial. In fact, incentives might serve to propagate negative reviews.

Third, moving beyond the manufacturer–customer relationship, our findings help clarify online reviewing behavior in general. Whether in an attempt to safeguard norms of prosocial behavior or to exclude others from its benefits, online retailers such as Amazon.com discourage independent solicitations of customer reviews by manufacturers (Amazon.com 2018), and the value of online reviews often gets questioned in public discourses, due to the potential for manipulation (Luca and Zervas 2016). Further research in this regard is certainly needed, but our results indicate that manufacturers’ incentives do not bias reviews, because review writers feel motivated to resist this influence. Marketers should frame the incentive offer in a way that fosters customers’ propensity for positive reciprocity and avoids triggering psychological costs, such as by highlighting how honest reviews aid other customers in making good choices. Such an approach would identify others (not the company) as the main beneficiaries of online reviews and avoid the appearance of “bribing” customers to write (positive) reviews. This tactic might mitigate potential negative reactions to the company, its product, or the act of online reviewing, and reduce the appearance of tampering with prosocial acts among customers.

Fourth, managers need to be aware that customer satisfaction influences the psychological mechanisms that are at work when customers evaluate incentive offers. Incentives negatively affect review valence via increased psychological costs, and this effect is stronger for customers who are only moderately satisfied. If a company offers goods or services with comparatively lower quality, incentives for reviews may amplify the negativity of the reviews. Online review incentives cannot conceal deficient product quality. Data on past customer behavior (e.g., from complaint management or past online reviews) might provide additional insights for targeting incentive offers in that previously dissatisfied customers could be excluded from campaigns.

Limitations, research opportunities and conclusion

Our research has three main limitations that may trigger continued research. First, we conducted scenario experiments with self-reported behavioral intentions as dependent variables. Although our studies have high internal validity, they might be limited by the generally low external validity of laboratory studies. A field study would be a valuable extension to our research program, revealing the effects of incentives on customers’ actual reviewing behavior. While we find an increase in review writing likelihood when incentives are given, using customer relationship management data, researchers could validate the reviewing likelihood–actual behavior link. Furthermore, generalizability of findings may be limited by our choice of study participants from two populations with typically lower income (Mturk panel participants/university students), who may be more inclined to perform an activity for a financial benefit (i.e. 10 USD gift card) than others.

Second, we focused on online review authors to investigate writing likelihood and online review valence as the dependent variables. In doing so, we ignored review characteristics other than the valence of the review. However, the length and quality of reviews are important review characteristics that influence readers’ evaluations of these reviews (e.g., Korfiatis et al. 2012; Lu et al. 2018; Mudambi and Schuff 2010; Pan and Zhang 2011). Reviews that readers perceive as more helpful likely have a stronger impact on their purchase behavior (Ludwig et al. 2013; Purnawirawan et al. 2012). Thus, additional studies could focus on incentive offers’ influences on review characteristics other than ratings, such as review length, quality and perceived helpfulness.

Third, we focused on one method to stimulate online reviews, namely, offering monetary rewards in exchange for writing and publishing them on a review site. Possibly, paying the customer the reward prior to the customer’s posting of a review could increase perceptions of positive reciprocity and psychological costs. Non-monetary rewards present another means to increase online reviews, as for example product testing (Kim et al. 2016). Here, the consumer receives a product for free or at a reduced price and commits to writing an online review in exchange. Typically, these product testers are not required to post positive reviews but instead are encouraged to express their honest opinions. Further research should compare these two practices and their effectiveness for increasing online review writing likelihood and valance, then evaluate if the related reciprocity gains and psychological costs differ.

In conclusion, our research makes several contributions to marketing and information systems research. We demonstrate that monetary incentives can more than double customers’ review publication likelihood, addressing an important marketing goal. We also provide evidence of the psychological mechanisms that determine consumers’ decisions when considering their responses to this marketing strategy, which is an important conceptual insight with regard to the concept of positive reciprocity. Finally, we offer practical advice on how companies can best apply review incentives as a marketing strategy that serves a dual purpose: increasing sales and gaining insights into customers’ assessments of a company’s goods and services.

Notes

Consistent with our directional hypotheses, we used one-tailed testing. According to Cho and Abe (2013, p. 1265), using two-tailed tests for directional hypotheses bears the risk of drawing “inaccurate or mistaken empirical conclusions at a given level of significance α.”

References

Abbey, J. D., & Meloy, M. G. (2017). Attention by design: Using attention checks to detect inattentive respondents and improve data quality. Journal of Operations Management, 53(1), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2017.06.001.

Abelson, R. P. (1959). Modes of resolution of belief dilemmas. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 3(4), 343–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/002200275900300403.

Amazon.com (2018). About customer reviews. https://www.amazon.com/gp/help/customer/display.html?nodeId=201967050. Accessed September 10, 2018.

Anderson, E. W. (1998). Customer satisfaction and word of mouth. Journal of Service Research, 1(1), 5–17.

Babić Rosario, A., Sotgiu, F., De Valck, K., & Bijmolt, T. H. A. (2016). The effect of electronic word of mouth on sales: A meta-analytic review of platform, product, and metric factors. Journal of Marketing Research, 53(3), 297–318. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.14.0380.

Bagozzi, R. P., Belanche, D., Casaló, L. V., & Flavián, C. (2016). The role of anticipated emotions in purchase intentions. Psychology & Marketing, 33(8), 629–645. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20905.

Barone, M. J., Bae, T. J., Qian, S., & d’Mello, J. (2017). Power and the appeal of the deal: How consumers value the control provided by Pay What You Want (PWYW) pricing. Marketing Letters, 28(3), 437–447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-017-9425-6.

Belanche, D., Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., & Guinalíu, M. (2019). Reciprocity and commitment in online travel communities. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 119(2), 397–411. https://doi.org/10.1108/imds-03-2018-0098.

Berger, J. (2014). Word of mouth and interpersonal communication: A review and directions for future research. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 24(4), 586–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2014.05.002.

Berger, J., & Iyengar, R. (2013). Communication channels and word of mouth: How the medium shapes the message. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(3), 567–579. https://doi.org/10.1086/671345.

Berger, J., Sorensen, A. T., & Rasmussen, S. J. (2010). Positive effects of negative publicity: When negative reviews increase sales. Marketing Science, 29(5), 815–827. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.1090.0557.

Biyalogorsky, E., Gerstner, E., & Libai, B. (2001). Customer referral management: Optimal reward programs. Marketing Science, 20(1), 82–95. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.20.1.82.10195.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York: Wiley.

Block, J., & Kuckertz, A. (2018). Seven principles of effective replication studies: strengthening the evidence base of management research. Management Review Quarterly, 68(4), 355–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-018-0149-3.

Burger, J. M., Sanchez, J., Imberi, J. E., & Grande, L. R. (2009). The norm of reciprocity as an internalized social norm: Returning favors even when no one finds out. Social Influence, 4(1), 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510802131004.

Burns, T. (1973). A structural theory of social exchange. Acta Sociologica, 16(3), 188–208.

Byrne, R. M. J., & McEleney, A. (2000). Counterfactual thinking about actions and failures to act. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 26(5), 1318. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.26.5.1318.

Caliendo, M., Fossen, F., & Kritikos, A. (2012). Trust, positive reciprocity, and negative reciprocity: Do these traits impact entrepreneurial dynamics? Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(2), 394–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2011.01.005.

Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Chang, T. S., & Hsiao, W. H. (2013). Factors influencing intentions to use social recommender systems: A social exchange perspective. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(5), 357–363. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0278.

Cheung, C. M. K., & Lee, M. K. O. (2012). What drives consumers to spread electronic word of mouth in online consumer-opinion platforms? Decision Support Systems, 53(1), 218–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2012.01.015.

Cheung, C. M. K., & Thadani, D. R. (2012). The impact of electronic word-of-mouth communication: A literature analysis and integrative model. Decision Support Systems, 54(1), 461–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2012.06.008.

Chevalier, J. A., & Mayzlin, D. (2006). The effect of word of mouth on sales: Online book reviews. Journal of Marketing Research, 43(3), 345–354. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.43.3.345.

Cho, H.-C., & Abe, S. (2013). Is two-tailed testing for directional research hypotheses tests legitimate? Journal of Business Research, 66(9), 1261–1266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.02.023.

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602.

Dellarocas, C., Zhang, X. M., & Awad, N. F. (2007). Exploring the value of online product reviews in forecasting sales: The case of motion pictures. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 21(4), 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.20087.

Dellarocas, C., Gao, G., & Narayan, R. (2010). Are consumers more likely to contribute online reviews for hit or niche products? Journal of Management Information Systems, 27(2), 127–158. https://doi.org/10.2753/mis0742-1222270204.

Dhar, V., & Chang, E. A. (2009). Does chatter matter? The impact of user-generated content on music sales. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 23(4), 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2009.07.004.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2008). Representative trust and reciprocity: Prevalence and determinants. Economic Inquiry, 46(1), 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.2007.00082.x.

Duan, W., Gu, B., & Whinston, A. B. (2008). Do online reviews matter? – An empirical investigation of panel data. Decision Support Systems, 45(4), 1007–1016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2008.04.001.

Eelen, J., Özturan, P., & Verlegh, P. W. J. (2017). The differential impact of brand loyalty on traditional and online word of mouth: The moderating roles of self-brand connection and the desire to help the brand. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 34(4), 872–891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2017.08.002.

Eisingerich, A. B., Chun, H. H., Liu, Y., Jia, H. M., & Bell, S. J. (2015). Why recommend a brand face-to-face but not on Facebook? How word-of-mouth on online social sites differs from traditional word-of-mouth. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25(1), 120–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2014.05.004.

Feng, J., Li, X., & Zhang, X. (2019). Online product reviews-triggered dynamic pricing: theory and evidence. Information Systems Research, 30(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2019.0852.

Fornell, C., Morgeson III, F. V., & Hult, G. T. M. (2016). Stock returns on customer satisfaction do beat the market: Gauging the effect of a marketing intangible. Journal of Marketing, 80(5), 92–107. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0229.

Fransen, M. L., Smit, E. G., & Verlegh, P. W. J. (2015). Strategies and motives for resistance to persuasion: an integrative framework. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1201. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01201.

Garnefeld, I., Eggert, A., Helm, S. V., & Tax, S. S. (2013). Growing existing customers’ revenue streams through customer referral programs. Journal of Marketing, 77(4), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.11.0423.

Gneezy, U., Meier, S., & Rey-Biel, P. (2011). When and why incentives (don’t) work to modify behavior. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(4), 191–210. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.25.4.191.

Grewal, L., & Stephen, A. T. (2019). In mobile we trust: The effects of mobile versus nonmobile reviews on consumer purchase intentions. Journal of Marketing Research, 56(5), 791–808. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022243719834514.

Gu, B., Park, J., & Konana, P. (2012). The impact of external word-of-mouth sources on retailer sales of high-involvement products. Informations Systems Research, 23(1), 182–196. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1100.0343.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

He, S. X., & Bond, S. D. (2015). Why is the crowd divided? Attribution for dispersion in online word of mouth. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(6), 1509–1527. https://doi.org/10.1086/680667.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K. P., Walsh, G., & Gremler, D. D. (2004). Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the internet? Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(1), 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.10073.

Ho-Dac, N. N., Carson, S. J., & Moore, W. L. (2013). The effects of positive and negative online customer reviews: Do brand strength and category maturity matter? Journal of Marketing, 77(6), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.11.0011.

Homans, G. C. (1958). Social behavior as exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 63(6), 597–606. https://doi.org/10.1086/222355.

Jin, L., & Huang, Y. (2014). When giving money does not work: The differential effects of monetary versus in-kind rewards in referral reward programs. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 31(1), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2013.08.005.

Karmakar, U. R., & Bollinger, B. (2015). BYOB: How bringing your own shopping bags leads to treating yourself and the environment. Journal of Marketing, 79(4), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.13.0228.

Kees, J., Berry, C., Burton, S., & Sheehan, K. (2017). An analysis of data quality: Professional panels, student subject pools, and Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Journal of Advertising, 46(1), 141–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2016.1269304.

Keiningham, T. L., Rust, R. T., Lariviere, B., Aksoy, L., & Williams, L. (2018). A roadmap for driving customer word-of-mouth. Journal of Service Management, 29(1), 2–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/josm-03-2017-0077.

Khern-am-nuai, W., Kannan, K., & Ghasemkhani, H. (2018). Extrinsic versus intrinsic rewards for contributing reviews in an online platform. Information System Research, 29(4), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2017.0750.

Kim, J., Naylor, G., Sivadas, E., & Sugumaran, V. (2016). The unrealized value of incentivized eWOM recommendations. Marketing Letters, 27(3), 411–421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-015-9360-3.

King, R. A., Racherla, P., & Bush, V. D. (2014). What we know and don’t know about online word-of-mouth: A review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 28(3), 167–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2014.02.001.

Kirmani, A., & Zhu, R. (2007). Vigilant against manipulation: The effect of regulatory focus on the use of persuasion knowledge. Journal of Marketing Research, 44(4), 688–701. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.44.4.688.

Kolbe, R. H., & Burnett, M. S. (1991). Content-analysis research: An examination of applications with directives for improving research reliability and objectivity. Journal of Consumer Research, 18(2), 243–250. https://doi.org/10.1086/209256.

Korfiatis, N., García-Bariocanal, E., & Sánchez-Alonso, S. (2012). Evaluating content quality and helpfulness of online product reviews: The interplay of review helpfulness vs. review content. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 11(3), 205–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2011.10.003.

Koslow, S. (2000). Can the truth hurt? How honest and persuasive advertising can unintentionally lead to increased consumer skepticism. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 34(2), 245–267. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2000.tb00093.x.

Kostyra, D. S., Reiner, J., Natter, M., & Klapper, D. (2016). Decomposing the effects of online customer reviews on brand, price, and product attributes. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 33(1), 11–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2014.12.004.

Kumar, V., Dalla Pozza, I., & Ganesh, J. (2013). Revisiting the satisfaction-loyalty relationship: Empirical generalizations and directions for future research. Journal of Retailing, 89(3), 246–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2013.02.001.

Lambe, C. J., Wittmann, C. M., & Spekman, R. E. (2001). Social exchange theory and research on business-to-business relational exchange. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 8(3), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1300/j033v08n03_01.

Lampel, J., & Bhalla, A. (2007). The role of status seeking in online communities: Giving the gift of experience. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(2), 434–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00332.x.

Lee, S., & Choeh, J. Y. (2016). The determinants of helpfulness of online reviews. Behaviour & Information Technology, 35(10), 853–863. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929x.2016.1173099.

Liu, Y. (2006). Word of mouth for movies: Its dynamics and impact on box office revenue. Journal of Marketing, 70(3), 74–89. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.70.3.74.

Lovett, M. J., Peres, R., & Shachar, R. (2013). On brands and word of mouth. Journal of Marketing Research, 50(4), 427–444.

Lu, S., Wu, J., & Tseng, S.-L. A. (2018). How online reviews become helpful: A dynamic perspective. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 44(4), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2018.05.005.

Luca, M. (2016). Reviews, reputation, and revenue: The case of Yelp.com. Harvard Business School Working Paper.

Luca, M., & Zervas, G. (2016). Fake it till you make it: Reputation, competition, and Yelp review fraud. Management Science, 62(12), 3412–3427. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2015.2304.

Ludwig, S., de Ruyter, K., Friedman, M., Brüggen, E. C., Wetzels, M., & Pfann, G. (2013). More than words: The influence of affective content and linguistic style matches in online reviews on conversion rates. Journal of Marketing, 77(1), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.11.0560.

Lydon, J., Zanna, M. P., & Ross, M. (1988). Bolstering attitudes by autobiographical recall: Attitude persistence and selective memory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 14(1), 78–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167288141008.

Mandel, D. R., Hilton, D. J., & Catellani, P. E. (2005). The psychology of counterfactual thinking. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Mandel, D. R., & Lehman, D. R. (1996). Counterfactual thinking and ascriptions of cause and preventability. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(3), 450–463. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.3.450.

Mathwick, C., & Mosteller, J. (2016). Online reviewer engagement: A typology based on reviewer motivations. Journal of Service Research, 20(2), 204–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670516682088.

McGrath, M. A., Sherry Jr., J. F., & Levy, S. J. (1993). Giving voice to the gift: The use of projective techniques to recover lost meanings. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 2(2), 171–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1057-7408(08)80023-x.

Meeker, B. F. (1971). Decisions and exchange. American Sociological Review, 36(3), 485–495. https://doi.org/10.2307/2093088.

Mende, M., Thompson, S. A., & Coenen, C. (2015). It’s all relative: How customer-perceived competitive advantage influences referral intentions. Marketing Letters, 26(4), 661–678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-014-9318-x.

Mills, J., & Clark, M. S. (1982). Exchange and communal relationships. Review of Personality and Social Psychology, 3, 121–144.

Moe, W. W., & Schweidel, D. A. (2012). Online product opinions: Incidence, evaluation, and evolution. Marketing Science, 31(3), 372–386. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.1110.0662.

Moldovan, S., Goldenberg, J., & Chattopadhyay, A. (2011). The different roles of product originality and usefulness in generating word-of-mouth. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 28(2), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2010.11.003.

Mudambi, S. M., & Schuff, D. (2010). What makes a helpful online review? A study of customer reviews on Amazon.com. MIS Quarterly, 34(1), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.2307/20721420.

Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 460–469. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150499.

Pan, Y., & Zhang, J. Q. (2011). Born unequal: A study of the helpfulness of user-generated product reviews. Journal of Retailing, 87(4), 598–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2011.05.002.

Park, S., & Nicolau, J. L. (2015). Asymmetric effects of online consumer reviews. Annals of Tourism Research, 50, 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.10.007.

Pew Research Center (2016). Online Shopping and E-Commerce. http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/12/19/online-shopping-and-e-commerce/. Accessed September 11, 2018.

Poch, R., & Martin, B. (2015). Effects of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation on user-generated content. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 23(4), 305–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254x.2014.926966.

Purnawirawan, N., De Pelsmacker, P., & Dens, N. (2012). Balance and sequence in online reviews: How perceived usefulness affects attitudes and intentions. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 26(4), 244–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2012.04.002.

Ringold, D. J. (2002). Boomerang effects in response to public health interventions: Some unintended consequences in the alcoholic beverage market. Journal of Consumer Policy, 25(1), 27–63. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1014588126336.

Roese, N. J. (1997). Counterfactual thinking. Psychological Bulletin, 121(1), 133–148.

Roese, N. J., & Olson, J. M. (1995). Outcome controllability and counterfactual thinking. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(6), 620–628. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167295216008.

Ryu, G., & Feick, L. (2007). A penny for your thoughts: Referral reward programs and referral likelihood. Journal of Marketing, 71(1), 84–94. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.71.1.84.

Sahoo, N., Dellarocas, C., & Srinivasan, S. (2018). The impact of online product reviews on product returns. Information System Research, 29(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2017.0736.

Schlosser, A. E. (2005). Posting versus lurking: Communicating in a multiple audience context. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(2), 260–265. https://doi.org/10.1086/432235.

Schmitt, P., Skiera, B., & van den Bulte, C. (2011). Referral programs and customer value. Journal of Marketing, 75(1), 46–59. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.75.1.46.

Shi, X., & Liao, Z. (2017). Online consumer review and group-buying participation: The mediating effects of consumer beliefs. Telematics and Informatics, 34(5), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2016.12.001.

Sridhar, S., & Srinivasan, R. (2012). Social influence effects in online product ratings. Journal of Marketing, 76(5), 70–88. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.10.0377.

Streitfeld, D. (2012). For $2 a star, an online retailer gets 5-star product reviews. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/27/technology/for-2-a-star-a-retailer-gets-5-star-reviews.html. Accessed July 4, 2018.

Thakur, R. (2018). Customer engagement and online reviews. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 41, 48–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.11.002.

Thomson, M., & Johnson, A. R. (2006). Marketplace and personal space: Investigating the differential effects of attachment style across relationship contexts. Psychology & Marketing, 23(8), 711–726. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20125.

von Wangenheim, F., & Bayón, T. (2007). The chain from customer satisfaction via word-of-mouth referrals to new customer acquisition. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35(2), 233–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0037-1.

Wirtz, J., Orsingher, C., Chew, P., & Tambyah, S. K. (2012). The role of metaperception on the effectiveness of referral reward programs. Journal of Service Research, 16(1), 82–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670512462138.

Wu, P. F. (2019). Motivation crowding in online product reviewing: A qualitative study of amazon reviewers. Information & Management, 56(8), 103163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2019.04.006.

Yang, Y., Gu, Y., & Galak, J. (2016). When it could have been worse, it gets better: How favorable uncertainty resolution slows hedonic adaptation. Journal of Consumer Research, 43(5), 747–768. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucw052.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Responsible Editor: Robert Harmon

Appendices

Appendix 1: Questionnaire (Study 1)

In the following, we are interested in learning about your thoughts and feelings about receiving a notecard from a product manufacturer that requests you to write an online review. Please complete the following sentences in as much detail as possible.

If I found such a notecard in the product package, my initial thoughts and feelings would be ….

If I found such a notecard in the product package and saw that there is an incentive offered for writing an online review, I would think …

If I found such a notecard in the product package, I would think that the product manufacturer …

If I found such a notecard in the product package, I would think that the product …

If I decided to write an online product review in response to such a notecard, I would feel ….

This is what I dislike about being offered an incentive for writing an online review:…

This is what I like about being offered an incentive for writing an online review:…

Age (“____ years“).

Gender (“female“/ “male“/ “other“).

Education (“8th grade or less”/ “Some high school, no diploma”/ “High school graduate, diploma or the equivalent (for example: GED)”/ “Some college credit, no degree”/ “Trade/technical/vocational training”/ “Associate’s degree”/ “Bachelor’s degree”/ “Master’s degree”/ “Professional degree (i.e. JD, Esq.)”/ “Ph.D./MD“)

Appendix 2: Pre-study (Study 3)

Research design and participants

To test our assumption that motivating dissatisfied customers with incentives is of low practical value, we analyzed the influence of incentive offers on dissatisfied customers. We conducted a scenario experiment with a posttest only control group design (Campbell and Stanley 1963) and manipulated the existence of an incentive offer (incentive offer vs. no incentive offer). Data were collected using an online survey with 126 participants. Average age was 37 years, and 54% were women. Participants were randomly assigned to the experimental groups.

Procedure and measures

All participants received a scenario description and a questionnaire. The experimental setting was similar to Study 3. The scenario described an online purchase of a fitness DVD and evoked a low level of satisfaction based on depicted experiences after testing the DVD in both groups. For the incentive manipulation, only the treatment group read that they received an incentive offer in return for writing an online review, with a notecard and a description comparable to the one in Study 2 and Study 3. Next, participants rated their intention to write an online review and the valence of that review as well as their satisfaction with the DVD. Finally, we asked for participants’ demographic data.

Results

First, we ensured that satisfaction was low as intended (M = 1.78). Second, the results revealed a significant direct effect of the existence of an incentive offer (F = 0.9; p = .057) on online review writing likelihood. When an incentive was offered, online review writing likelihood increased (MControl = 30.2, SDControl = 33.0; MIncentive = 41.7, SDIncentive = 34.4). Third, online review valence was not influenced by the incentive (MControl = 1.9, SDControl = 0.9; MIncentive = 1.9, SDIncentive = 0.9).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article