Abstract

This study aims at establishing a historically based model of animal husbandry in urban and rural settlements, in the Southern Levant. This type of model is required in the field of zooarchaeology, to better analyze and study ancient faunal remains. It also applies a non-traditional method to study and differentiate between urban and rural economies. For this aim, we used British Mandate tax files and village statistics. These are the best available historical documents for this period, that recorded herds management statistics in all settlements of Palestine. We selected only settlements inhabited by the indigenous population and divided the data into four environmental regions. We analyzed the livestock abundance and herd demography in each region. Each urban center was considered independently, while the rural villages were classified into three groups, based on the most common livestock (cattle, sheep, or goats). Results show economic variations between urban and rural settlements as well as regional trends, such as in pastoralism and agricultural management. In addition, meat industries were common in most urban centers, being the primary difference from rural economies. We applied this model to two large zooarchaeological case studies, dating from the Early Islamic to the Ottoman period; Mount Zion, located in the urban city of Jerusalem, and Tel Beth Shemesh (East), whose size and nature were not historically recorded. We found that the economic variations reflected in the model were also present in the faunal assemblages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Zooarchaeological studies offer a significant source of knowledge about past diets, culture, economy, and subsistence strategies (Davis 1987; pp. 20–22). The ancient livestock economy and herds management strategies are fundamental subjects, discussed in zooarchaeological studies of all periods. Often, interpretation of the zooarchaeological data from the Southern Levant, and especially the reconstruction of animal exploitation and local economy, relies on ethnographic research (see, e.g., Helmer & Gourichon, 2007; Helmer and Vigne 2004; Redding 1984), or textual records (mentionedin Zeder 1991). However, these analogies represent distant cultures and environments, and it is not certain how accurate they are to the Southern Levantine area. Thus, a new methodological theory is required to better analyze and study the faunal remains, and to assist in differentiating between urban and rural economies.

Zooarchaeological studies of the Late Ottoman period and the first half of the 20th century CE are scarce (see, e.g., Holzer et al. 2010), and, therefore, cannot serve as a benchmark for interpreting earlier assemblages. Fortunately, during the 1930s and the 1940s CE, the administrational records of the British Mandate authorities (who ruled over Palestine between 1920 and 1948) documented human and animal population statistics (see below, The Mandate tax files). Thus, one possible avenue for solving this problem would be to look at the animal economy of the region during the pre-modern era (19th and early 20th centuries CE), which was recorded in government administrative documents.

We acknowledge that modernization and the industrial revolution influenced the general population as well as agriculture and farming practices, in the early years of the British Mandate period. These advances resulted in the growth of the human population and urban meat markets (Gilad 2022). Still, we assume that traditional practices were retained from the previous Islamic and Ottoman periods, since most of the human population in Palestine were Muslims (Igra 2019). According to Nadan (2006), the Muslim fallāḥīn (which means ‘peasants’ or ‘farmers’) culture was not altered in the way that the Jewish economy was. The ethnonational segregation led to the development of labour-intensive agriculture in the Jewish sector, but not in the Arab segment (Nadan 2006; p. 5).

These tax files offer records of the livestock demography in each settlement in Palestine, and thus, hold a potentially unique contribution to the zooarchaeological study. This database opens a window through which one may study the livestock economy of this region (Fleet 2014; p. 456, see additional details below). In this study, we sought to utilize these records to establish a historically based model of animal husbandry in the Southern Levant. This model will (1) classify and differentiate between different economic behaviors of urban and rural villages, and (2) differentiate between rural economies in different environmental regions. We further examined our model on two large zooarchaeological case studies, an urban center, and a rural village, dating from the Early Islamic to the Ottoman period.

Materials and methods

The mandate tax files

The database used in this study was retrieved from British village statistics, which are the best available historical documents for the previous Islamic and Ottoman periods in the Southern Levant. The British authorities recorded human population statistics (Government of Palestine 1945), livestock enumerations (Government of Palestine 1943), tax registrations (Government of Palestine 1931), and animal regulations (Government of Palestine 1946). Most documents were written in English, while some were written in Hebrew or Arabic, and a great number of them were handwritten.Footnote 1

During the Ottoman period, three main taxes were applied, and collected once a year: the tax on house and land properties (werko), the tax on 12.5% of the peasants’ gross yield of agricultural income (tithe), and the tax on livestock (Aghnam) (El-Eini 1997). These taxes were implemented by the British Mandate administration. The Aghnam tax was collected only for grazing animals, while those that were used solely for ploughing were exempt from taxation (Bunton 2007; p. 141). Still, all livestock numbers (grazing and ploughing) were reported to the government by the appointed heads of the settlements (mukhtars), who collected the data during February and March, before the tax assessment (Roza 2006; pp. 225–226).

It should be noted, however, that these tax statistics are not a direct reflection of reality since they were based on statistical estimation and not an actual census. The primary reason for this is the difference between the high taxes on holding livestock, compared to the lower market values of dairy and meat commodities, which would have bound the peasants to pay more than they earned. Moreover, the peasants did not always know the exact tax range they were obliged to pay, as the mukhtars (the village head) often made up their prices. The mukhtars also concealed information regarding their own families’ livestock, to avoid paying (Roza 2006; p. 226). Therefore, while some producers reduced the breeding cycles of their flocks, others decided to conceal the true number of the livestock, sometimes by bribing government agents (Akarli 1992). In the Beersheba district, the local tribes refused to share information regarding their livestock, and therefore a general estimation was provided by the local district officer (Nadan 2006; p. 99).

The livestock enumerations that were recorded for every sub-district in Palestine, documented the total number of livestock held in each settlement, including data on animals’ sex (females or males) and age groups (recorded as less than one year, under three years, and over three years). For female cattle, sheep, and goats, further status categories were recorded: their exploitation for work or milking, and if they were with or without an offspring (referred to in the files as “a kid”).

Animals such as pigs and chickens do not appear in the Livestock Enumeration. While chickens were exempt from taxation, pigs were highly taxed and even documented in tax files from 1939–1940 Jerusalem (Government of Palestine 1947). Pigs were listed in the tax rule that continued from the Islamic into the Mandate period (and was between 100–400 milsFootnote 2 from 1922 until 1945). While less expensive to hold than the larger livestock, they were more expensive than sheep and goats (Government of Palestine 1946; p. 543). Pigs were raised almost solely by Arab Christians, while only a few Muslims and Jewish people were involved in pig breeding (Gilad 2022).

While being aware of these limitations, the documents still offer a view of the animal economy that is close enough to reality and on average represents the economic strategy of the Southrn Levantine society at the turn of the century. We chose to use the Livestock Enumeration tax files (Government of Palestine 1943) in this study, as they supply sound estimations that document trends in livestock, their demographic distribution, and their economic function.

The mandate settlements classification

During the British Mandate period, Palestine was divided into six districts for administration purposes (including the districts of Galilee, Haifa, Samaria, Jerusalem, Lydda, and Gaza), as can be found in the Human Population Statistics (Government of Palestine 1945). The British authorities addressed in this document the nature of the different settlements as either ‘urban’, ‘rural’, or ‘nomadic. A further classification of the population included the religious identity of the local population, i.e., ‘Muslim’, ‘Jewish’, ‘Christian’, and ‘Others’. Urban settlements included (1) the four largest towns: Jerusalem, Tel-Aviv, Haifa, and Jaffa; (2) the chief town of each sub-district (which were also the names of the sub-district), e.g., Gaza; and (3) towns with a central municipality and councils (both Arab and Jewish). Rural settlements were all other locations not addressed as ‘urban’. ‘Nomadic’ refers to all Bedouin tribes located at the Beer-Sheba sub-district.

The result of this three-tier classification is that most settlements were agglomerated in our study into the category considered ‘rural villages’, although each village could have different economic strategies. For example, some villages practised agriculture, others specialized in milk production, and some could have incorporated both practices. No other administrative categorization was found in the historical-geographical literature of this period, as most studies used only the broad terminology of ‘urban’ and ‘rural/village’ (e.g., Frenkel 1995; Gross 1976).

Recording and further analysis of the files

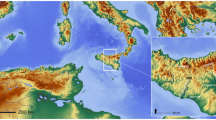

By analyzing the historical records, we aimed to distinguish between urban and rural economies, as well as different types of rural villages. To do so, we selected only settlements inhabited by the indigenous population and divided the data based on the four main regions of Palestine (Fig. 1), which have similar Mediterranean climate conditions. The Northern region (northern coastline and Galilee highlands, based on data from the district of Haifa) includes 37 settlements; the Central Coast region (coastline, based on data from the district of Lydda/Jaffa) includes 26 settlements; the Eastern Region (Judean hills and Shephelah, based on data from the district of Jerusalem) includes 77 settlements; and the Southern Coast Region (southern coastline and inland, based on data from the district of Gaza) includes 57 settlements (see in Supplementary material: Table S1, based on Government of Palestine 1943).Footnote 3

We analyzed the livestock abundance and herds demography in urban and rural villages separately, in each region. Each urban center was considered separately, as there was only one in each region. Rural villages were classified into three groups, based on the most common livestock in each village: cattle, sheep, or goats.

A map of historical Palestine, with the division of the four geographical regions, including their main urban centers: Northern region and and the urban center of Haifa (in blue), Central Coast region and the urban center of Jaffa (in green), Eastern region and the urban center of Jerusalem (in red), and Southern Coast region and the urban center of Jaffa (in yellow). The area to the south (Be’er Sheva district) was not included, as it contains only nomadic tribes who did not supply information of their livestock to the authorities

Results

Seven animals were documented in the Livestock Enumeration tax files: cattle, sheep, goats, camels, horses, mules, and donkeys. Their distribution, as well as herd demography and management strategies, varies between settlements and regions. We present here the livestock economy of urban and rural settlements, by region.

Northern region

Grouping all the livestock in villages that were part of the Northern region, displays the livestock abundance of this region. Results show that the most common livestock in the north were goats (represented 56% of all livestock in the Northern region combined), followed by cattle (21%), and sheep (13%). In our classification of the rural villages into three groups, based on the most common livestock, we found that 25 villages raised mainly goats, nine villages raised mainly cattle, and only two villages raised mainly sheep. Donkeys were also rather common (8%), while other livestock such as horses, camels, and mules were rare (less than 2%). In contrast to the villages, in the urban center of Haifa, the most common livestock were sheep (38% of all livestock in Haifa), followed by goats (28%), cattle (12%), and horses (11%). Donkeys and camels were equally represented (5%), and mules were almost absent (0.2%) (Fig. 2).

Livestock frequencies in rural and urban settlements by region. Based on Livestock Enumeration tax files (Government of Palestine 1943). The urban center of Haifa is located in the Northern region, the urban center of Jaffa is located in the Central Coast region, the urban center of Jerusalem is located in the Eastern region, and the urban center of Gaza is located in the Southern Coast region

All three types of villages raised their caprines for milk, as all included mostly adult females over one year, under the category of ‘milking or about to lamb’. The second largest age group was young caprines under one year. Adult females who could not deliver more milk were under the category of ‘not in kid and dry’, and were more frequent than adult males, who represented less than 5% of the entire herd. In contrast to the villages, in the urban center of Haifa, most sheep and goat herds were dominated by immature males under one year (72% of the goats’ herd and 47% of the sheep herd). A decrease in male frequencies occurred following the age of one year (3% of the goats’ herd and 13% of the sheep herd). Adult females were under the category of ‘milking or about to lamb’, and were the second most common in those herds (Fig. 3).

In all three types of villages, cattle were raised mainly for dairy, as adult females over three years, under the category of ‘dairy cows’, were most common. Younger females between one and three years were also common, followed by calves under one year. Males between one and three years were less common than females of the same age, while adult bulls, over three years, were the least common in all herds. Some adult cattle, over three years, were recorded under the category of ‘working oxen’ or ‘working cows’. Between these two, the males were almost always more common than the females, except in villages that raised mainly sheep. And still, even if we combine their numbers under the category of ‘working cattle’, they were always less frequent than the ‘dairy cows’ (Fig. 4).

Central Coast region

Grouping all the livestock in villages that were part of the Central Coast region, displays the livestock abundance of this region. Results show, that the most common livestock in the center, were cattle (represented 41% of all livestock in the Central Coast region), followed by sheep (23%), and goats (17%). In our classification of the rural villages into three groups, based on the most common livestock, we found that 15 villages raised mainly cattle, eight villages raised mainly sheep, and only two villages raised mainly goats. Donkeys were also rather common (10%), while other livestock such as horses, camels, and mules were less common (represented less than 4%). In contrast to the villages, in the urban center of Jaffa, the most common livestock were goats (45% of all livestock in the Jaffa), followed by cattle (21%), sheep (15%), donkeys (9%), and horses (6%). Camels and mules were less common (represented by less than 2%) (Fig. 2).

All three types of rural villages raised sheep and goats for milk as adult females over one year, and under the category of ‘milking or about to lamb’, were most common. Adult males were the least represented. Only one village (El Muweilih, under the category of villages that raised mainly cattle), did not raise any sheep or goats. This village focused on raising only cattle, for dairy. In villages that raised mainly sheep, the young males’ frequencies were higher in comparison to the milking females (Fig. 5).

In the Urban center of Jaffa, goats and sheep presented a different demographic profile. The goats’ herds were raised for milk and included mostly females under the category of ‘milking or about to lamb’, followed by young offspring under one year, and a few adult males. The sheep herd included mostly young males under one year and almost equal numbers of adult males and females. Adult females under the category of ‘not in kid and dry’, were least represented (Fig. 5).

Much like caprines, in all three types of villages, cattle were also raised for milk. Cattle herds included mostly females under the category of ‘dairy cows’, followed by calves under one year, and young-adult females between one and three years. Young adult males were least represented, while ‘working cows’ and ‘working oxen’ were almost absent. In the urban center of Jaffa, most of the cattle herd included ‘dairy cows’. And yet, in contrast to the villages, there was also a rather high frequency of ‘working cows’ and young-adult males between one and three years (Fig. 6).

Eastern region

Grouping all the livestock in villages that were part of the Eastern region, displays the livestock abundance of this region. Results show, that the most common livestock in the east, were goats (represented 47% of all livestock in the Eastern region), followed by sheep (34%), and cattle (11%). In our classification of the rural villages into three groups, based on the most common livestock, we found that 59 villages raised mainly goats, 16 villages raised mainly sheep, and only one village raised mainly cattle. Donkeys were also rather common (6%), while other livestock such as horses, camels, and mules were less common (less than 2%). In contrast to the villages, in the urban center of Jerusalem, the most common livestock were sheep (45% of all livestock in Jerusalem), followed by goats (35%). Cattle and donkeys were equally represented (8%). Similar to the villages, camels, horses, and mules were also uncommon in Jerusalem (less than 3%) (Fig. 2).

All three types of rural villages in the Eastern region raised sheep and goats for dairy. These herds included mostly females under the category of ‘milking or about to lamb’ (represented almost 50% of the herds), and immature offspring under one year. Adult males were the least common and represented less than 3% of the herd. Adult females under the category of ‘not in kid and dry’, were present in all villages, except in goat herds in villages that raised mostly sheep (Fig. 7).

In contrast to the villages, in the urban center of Jerusalem, we found different management strategies for sheep and goats. For goats, immature offspring were the majority of the herd (62% of the herd), immature females and males equally represented. Adult female goats under the category of ‘milking or about to lamb’ were second most common, and represented only 30% of the herd. Adult female goats under the category ‘not in kid and dry’ were less common (8%), and adult males were almost absent (0.5%). For sheep, the majority of the herd were adult males (35% of the herd). Adult females under the category of ‘milking or about to lamb’ were the second most common (28%) (Fig. 7).

Cattle herds were managed differently between the three types of villages that we defined. In villages that raised mainly sheep or mainly goats, most cattle were used for work. But villages that raised mainly cattle held mostly ‘dairy cows’, and young-adult cows (between one and three years), as well as immature calves. They reported no cows or oxen used for work, as well as no bulls for reproduction. These villages that raised mainly cattle, practised an animal economy that is similar to the urban center of Jerusalem. There, the preference was to raise mostly ‘dairy cows’, which represented more than half of the herd (61%). Although ‘working cows’ and ‘working oxen’ were present, they represented together only 5% of the herd (Fig. 8).

Southern Coast region

Grouping all the livestock in villages that were part of the Southern Coast region, displays the livestock abundance of this region. Results show, that the most common livestock in the south, were sheep (represented 38% of all livestock in the Southern Coast region), followed by cattle (26%), donkeys (17%), and goats (11%). In our classification of the rural villages into three groups, based on the most common livestock, we found that 31 villages raised mainly sheep, 21 villages raised mainly cattle, nine villages raised mainly donkeys, and only four villages raised mainly goats. Camels were also common (6%), while other livestock such as horses, and mules were rare (less than 1%). In the urban center of Gaza, the livestock abundance was almost the same as in the villages. The most common livestock were sheep (37% of all livestock in Gaza), followed by donkeys (28%), cattle (14%), and camels (12%). Horses and mules were the least common livestock (less than 2%) (Fig. 2).

All three types of villages in the Southern Coast region, as well as the urban center of Gaza, managed their sheep and goats similarly. All herds included adult females under the category of ‘milking or about to lamb’ and immature offspring, in almost equal representation. Only in villages that raised mainly sheep, or mainly goats, in herds of sheep, we find adult females under the category ‘not in kid and dry’ (Fig. 9).

Cattle were raised for both milk and work in all three types of villages, as well as in the urban center of Gaza. In villages that raised mainly sheep or goats, most cows were managed for work. In contrast, in villages that raised mainly cattle, and in the urban center of Gaza, more ‘dairy cows’ were present. In all rural and urban settlements, ‘working oxen’ were rather rare (between 2–3% of the herd) (Fig. 10).

Discussion

The historical study presented here demonstrates that while the core of every economy relied on sheep, goats, cattle, donkeys, camels, horses, and mules, the livestock abundance and herds management strategies were not uniform. The crucial part of most livestock economies was based on herding sheep and goats, but their distribution differed between regions - in the north and east, villages preferred to raise mainly goats, in the center mainly cattle, and in the south mainly sheep.

These preferences demonstrate that in this period, climate was not the major factor dictating livestock husbandry. If the local environment had a major influence, it is expected that goats, which are more suitable for the mountain-dry environment would be dominant in the south, and that sheep and cattle would be dominant in the plain-moist areas in the north (Redding 1984; Tchernov and Horwitz 1990). We can thus only assume that the cultural and traditional aspects of the local settlements influenced their economic preferences.

Based on the results of this study, we found regional trends in the livestock abundance and herds’ demography, of urban and rural settlements. Herds management strategies were reflected in two economic components. The first component is pastoralism, which is the practice of keeping livestock for primary and/or secondary subsistence (Little 2015). This type of economy usually occurs in permanent settlements, located in arid, semiarid, and sub-humid areas (Waters-Bayer and Bayer 1992). In each village, there was usually one shepherd, who managed all flocks (Lees 1905; p. 98). During most of the year, the herds were kept at the site and pastured locally. A seasonal movement of the herds occurred during the winter, as they were grazing between arid and semiarid or humid zones, or from the valley to mountain pastures (Brown 1939; pp. 173–178; Nadan 2006; p. 107; Weber and Horst 2011). The second component is agriculture, which is documented in the tax files under ‘working oxen’ and ‘working cows’. In this model, the ratio between ‘dairy cows’ and ‘working cows/oxen’, will determine if agriculture was subsidiary or primary to dairy production.

The Northern region economy

The rural economy of the Northern region focused mainly on raising goats, and the exploitation of caprines and cattle for dairy. Agriculture was only subsidary of dairy production, as more cows were exploited for milk rather than work (Fig. 11).

The urban economy of the Northern region is expressed through the urban center of Haifa. The economy focused mainly on raising sheep. In this city, there was a preference for young male sheep, goats, and cattle, which were slaughtered for meat before the age of one year. This strategy suggests that a meat industry took place in the city, and that the inhabitants favored young and tender meat. This is in contrast to the villages, that raised their herds to adulthood, and culled them only when they were no longer economically profitable. In addition, agriculture was considered negligible, compared to dairy production, as working cows were very rare (Fig. 12). Donkeys were probably used in some range for agriculture, although based on their low frequency they might not have been a crucial substitute for working cattle.

Unusually common livestock found in Haifa, and was almost absent in other regions, was the horse. The high occurrence of horses in the city may suggest that they were raised as free-ranging, which was possible thanks to the open grazing fields, green grass, plenty of water sources, and comfortable climate of the north. These aspects are why horse ranches are common in the North of Israel until today. The high appearance of horses in this area could also relate to the Haifa port. Horses could have been used to transfer the commodities that arrived by ships, or been the commodities themselves, while brought from Europe to be used by the British army (Igra 2019).

Summarising model for rural and urban economic variations, in the Northern region. The most common livestock in each type of economy is mentioned first, followed by livestock management strategies under two categories: Pastoralism- herding, and Agriculture- cattle management for work. Last, is the Economic classification- demonstrating the specialization or generalisation of the economy, based on the relations between herding and agriculture

The Central Coast region economy

The rural economy in the Central Coast region focused on raising cattle, and the exploitation of cattle, sheep, and goats for dairy. Agriculture was not practised in this region by cattle, as no cows and oxen were held for work, while all cows were exploited only for milk (Fig. 12). These villages also raised many donkeys and mules, which could have been used for different activities, such as trade and transportation, as well as cereal cultivation.

The urban economy of the Central Coast region is expressed through the urban center of Jaffa. The economy focused mainly on raising goats, and the exploitation of goats and cattle for dairy. In this city, in contrast to the villages, there was a preference to raise young and adult male sheep. Similar to the urban center of Haifa in the Northern region, another meat industry was probably practiced in the Central Coast urban area. Agriculture was only subsidary to dairy production, as more cows were exploited for milk rather than work (Fig. 12).

Summarising model for rural and urban economic variations, in the Central Coast region. The most common livestock in each type of economy is mentioned first, followed by livestock management strategies under two categories: Pastoralism- herding, and Agriculture- cattle management for work. Last, is the Economic classification- demonstrating the specialization or generalisation of the economy, based on the relations between herding and agriculture

The Eastern region economy

The rural economy of the Eastern region, focused on raising goats, and the exploitation of cattle, sheep, and goats for dairy. Although cattle were used primarily for work, their frequency was still lower than sheep and goats in these villages. Thus, agriculture was still subsidiary of dairy production (Fig. 13).

The urban economy of the Eastern region is expressed through the urban center of Jerusalem. In this city, similar to the urban center of the Northern region, we found a specialized cows’ dairy economy and combined caprines’ meat industry. This industry favoured young and adult goats’ meat, and mature sheep meat, slaughtered over the age of one year. In addition, agriculture was considered negligible, compared to dairy production, as working cows were very rare (Fig. 13).

Summarising model for rural and urban economic variations, in the Eastern region. The most common livestock in each type of economy is mentioned first, followed by livestock management strategies under two categories: Pastoralism- herding, and Agriculture- cattle management for work. Last, is the Economic classification- demonstrating the specialization or generalisation of the economy, based on the relations between herding and agriculture

The Southern Coast region economy

The rural economy of the Southern Coast region, was rather generalized. It focused on raising sheep, and the exploitation of sheep, cattle, and goats for dairy. In addition to dairy production, agriculture was commonly precticed, as the frequencies of working cows and oxen were high. In contrast to sheep, goat herds did not include any adult females under the category of ‘not in kid and dry’. That can mean, that goats were not kept past their fertility stage and were slaughtered, or sold for meat when they could no longer produce milk. Adult sheep were kept past their fertility stage, perhaps as they were also used for wool (Fig. 14).

The urban economy of the Southern Coast region is expressed through the urban center of Gaza. The economy focused mainly on raising sheep, and the exploitation of sheep, cattle, and goats for dairy. Agriculture was only subsidiary of dairy production, as more cows were exploited for milk rather than work (Fig. 14).

Donkeys were the most common of all beasts of burden, in both the villages and the urban center of Gaza. Their high frequencies could result from their low price, easy character, and suitable physics for different environments (Nadan 2006; pp. 65, 173). Camels were less common than donkeys, but their frequencies in this area were higher than in other regions. The proximity to the desert area was possibly the reason, as this is the camels’ natural habitat. And yet, camels were also found outside of their habitat, in the urban center of the Northern region (Haifa). Their arrival in this area could have resulted from human intervention, which brought them for purposes of status and luxury means of transportation.

Summarising model for rural and urban economic variations, in the Southern Coast region. The most common livestock in each type of economy is mentioned first, followed by livestock management strategies under two categories: Pastoralism- herding, and Agriculture- cattle management for work. Last, is the Economic classification- demonstrating the specialization or generalisation of the economy, based on the relations between herding and agriculture

Re-evaluating urban and rural zooarchaeological assemblages

After classifying the settlements into different types of economies, we wanted to validate and examine whether the model can be applied to interpreting zooarchaeological assemblages. We specifically chose sites dated from the Early Islamic to the Ottoman periods as the Islamic-based empires (that ruled Palestine from the Early 7th century CE until 1917, excluding the 12th and 13th centuries), enabled the development of unique religious, social, and economic patterns alongside interactions with surrounding cultures. Festive religious events, dietary codes, and taboos as well as regional connections, all shaped a unique animal economy that impacted the region for many generations (Baram & Carroll, 2002).

The first site is Mount Zion (Area I), located inside the walls of the urban center of Jerusalem. This site was chosen due to its known historical background. The site suffered a massive destruction during the earthquake of the 8th century CE and was rebuilt as an industrial courter later, in the Abbasid period. During the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, the site’s economy was based mainly on sheep, as well as goats, pigs, cattle, and fish. Sheep and goats were mostly adult females and castrated males, as well as adult cattle (Namdar & Sapir-Hen, 2023; Namdar et al., 2024).

The livestock economy of Mount Zion fits with the economy of Jerusalem in this study. We summarize the results from Mount Zion here and the full analysis and data can be found in (Namdar & Sapir-Hen, 2023; Namdar et al., 2024): In both Mandatory Jerusalem and Islamic Mount Zion , caprines (sheep and goats), were the most abundant livestock (42% of all identified specimens in Mount Zion). Both sites showed a preference for raising mostly sheep (9% of all identified specimens in Mount Zion, with goats represented 5% and cattle 4%). Based on the demographic profiles of sheep and goats (these were kept to adulthood with a few individuals culled before one year of age, and most goats were identified as females), we concluded that the Mount Zion population specialized in dairy production. Based on the high frequency of castrated adult males (a probability of 31.3% of castrated males, vs. a probability of 68.6% of females, based on Mixture Analysis of distal humeri LSI values), we can also suggest that Mount Zion relied on a local meat industry. Agriculture was subsidiary of dairy, based on the cattle’s survivorship to adulthood (44% of the elements fused between 3.5 and four years). That can mean, that most vegetables arrived from other settlements and were traded in the local markets. Donkeys, mules, and camels were also common in Jerusalem, and although in Mount Zion they were rather rare, possibly they were used for work and transportation.

The second site is Tel Beth Shemesh (East) (Namdar et al. 2022; Namdar & Sapir-Hen, in press), whose size and nature were not found in any existing historical records. Tel Beth Shemesh (East) located in the Shephelah, was a large settlement with a long human occupation, dating from the Bronze Age until the Late Ottoman period (Gross 2021). During the Umayyad, Mamluk, and Ottoman periods, caprines (sheep and goats), were the most abundant livestock (62% in the Late Byzantine/Early Islamic period; 36% in the Late Mamluk/Early Ottoman period; and 47% in the Late Ottoman period), implying that the sits’ economy was based mainly on herding goats. Both caprines and cattle were raised to adulthood (over four years), while some were culled young before one year of age. These age profiles suggest that caprines were probably managed for dairy, while cattle could have been exploited for dairy and work. Additional paleopathologies identified on cattle’s phalanges suggest degenerative joint diseases caused by old age and stress from hard work (Namdar & Sapir-Hen, in press).

Indeed, in accordance with our suggested model of villages in the Eastern region, in Tel Beth Shemesh (East), cows and female caprines were exploited for dairy production, while other cows and oxen were probably used for agriculture. This type of management also fits with the research made on a specific herd of goats, that was killed by the 8th century CE earthquake (Namdar et al. 2022). This herd stayed in confinement during the winter (such as in pens) and grazed near the site during the summer. Moreover, the fact that villages in the Eastern region that raised mainly goats did not keep the females past their fertility stage, corresponds with the management strategies of the Umayyad goat herds in Tel Beth Shemesh (East).

Conclusions

In this study, we used, for the first time, historical tax files from Mandatory Palestine, to comprise the livestock economy of urban and rural settlements. The documented data was available from one tax year (1943), and specifically two months of this year (February and March). Yet, no similar documents were available from other months and years. Thus, this historical source should be addressed as a unique sample case study, in a statistical research. We emphasize here that the final goal is to examine this model in comparison to faunal remains. Most often, in zooarchaeology, it is not possible to assess the assemblage’ specific year and month, and the faunal remains are often attributed to a long period. We are aware of the fact that human-animal relations are specific to time and place and should be studied within their context. We, therefore, focused the model on general trends noticed and did not include variables that can be explained by short-term cultural, economic, or technological considerations.

The overall aim of this study was to analyze the statistical data to offer a new, local analogy for the general livestock management strategies in the Southern Levant. The data retrieved from these files displayed various ways in which farmers and herders operated their herds and the local economy. We found that all settlements were fundamentally herders, who raised sheep and goats for dairy, while the frequencies of these animals varied between regions. We found that:

-

1.

The differences in livestock abundance between regions, were unrelated to the local climate.

-

2.

Urban and rural settlements from the same region, differ in their economy.

-

3.

Meat industries of caprines were common in most urban centers, being the primary difference from rural economies. We found a preference to raise adult male sheep in urban settlements, which did not occur in the villages.

-

4.

Rural villages had a more generalized economy, combining pastoralism and agriculture. Regarding herding, the primary aim was for dairy, while each region specialized in dairy production of either caprines or cattle.

-

5.

Unlike most villages, those in the Eastern region and Southern Coast region, that raised mainly goats, exploited them for meat. Sheep, on the other hand, were held to older ages, as they could be used for wool.

-

6.

Cattle management was more variable. All settlements, urban and rural, exploited cattle for dairy. The exploitation for work was less frequent but existed in most villages on different scales. That is, in villages in the Northern and Eastern regions, agriculture was subsidiary to dairy; in the Central Coast region, villages did not practice agriculture; and in the Southern Coast region, dairy and agriculture were relatively equally practised.

-

7.

Other livestock, mostly donkeys and mules, were also rather common, implying their incorporation into trade activities, and transportation. In the Central Coast region, donkeys and mules were possibly substituted for cattle in agriculture and cereal cultivation.

Finally, we reviewed two zooarchaeological assemblages of urban and rural settlements, dating to the Islamic and Ottoman periods. We found mutual traits in the faunal material of Mount Zion, located inside the urban center of Jerusalem (of the Eastern region), to the historically documented economy of Jerusalem. Further, the rural village of Tel Beth Shemesh (East), complies with the rural characteristic of the Eastern region. These results validate our suggested model.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Notes

The documents can be accessed through the Israel state archive in Jerusalem, and online: https://www.archives.gov.il. We wish to thank Israel Finkelstein for allowing us access to his copy of the documents and to Roy Marom for sharing with us his understanding of the documents’ value.

“Mil” (Palestine pound, جنيه فلسطيني, לירה ארץ ישראלית- לא"י)- The common coin during the British mandate. Exchange rate: 1 shekel = 10 mils.

We excluded sites located in the desert region as the climatical conditions in these regions lead to a very different livestock profile.

References

Akarli ED (1992) Economic Policy and budgets in Ottoman Turkey, 1876–1909. Middle East Stud 28(3):443–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/00263209208700910

Baram, Carroll (2002) A historical archaeology of the Ottoman Empire: breaking New Ground. Kluwer Academic

Brown M (1939) Agriculture. In: Himadeh SB (ed) Economic organization of Palestine. American University of Beirut, pp 111–211

Bunton MP (2007) Colonial land policies in Palestine, 1917–1936. Oxford University Press

Davis SJM (1987) The archaeology of animals. B. T. Batsford

El-Eini RIM (1997) Government Fiscal Policy in Mandatory Palestine in the 1930s. Middle East Stud 33(3):570–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/00263209708701169

Fleet K (2014) The Ottoman Economy, c. 1300-c. 1585. History Compass 12(5):455–464

Frenkel Y (1995) Rural Society in Mameluke Palestine. 77:17–38

Gilad E (2022) Camel Controversies and pork politics in British Mandate Palestine. Global Food History 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/20549547.2022.2106074

Government of Palestine (1931) Palestine. Blue Book. 1930

Government of Palestine (1943) Livestock Enumeration

Government of Palestine (1945) Village Statistics. 1–33

Government of Palestine (1947) Animal Enumeration Jerusalem Town

Government of Palestine (1946) A survey of Palestine, vol 1. Government printer, Palestine

Gross N (1976) Economic changes in Eretz Israel at the end of the Ottoman Period (in Hebrew). Cathedra: History Eretz Isr Its Yishuv 2:111–125

Gross B (2021) The other side of Beth Shemesh: salvage Archaeology exposes deep history of famed biblical site. Bible History Dly, 28

Helmer D, Vigne J-D (2004) La Gestion des Cheptels de Caprine

Helmer D, Gourichon L, Vila E (2007) The development of the Exploitation of products from Capra and Ovis (meat, milk and fleece) from the PPNB to the early bronze in the Northern Near East (8700 to 2000 BC cal). Anthropozoologica 42(2):41–69

Holzer A, Avner U, Porat N, Horwitz LK (2010) Desert kites in the Negev desert and northeast Sinai: their function, chronology and ecology. J Arid Environ 74(7):806–817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2009.12.001

Igra A (2019) Mandate of Compassion: Prevention of Cruelty to animals in Palestine, 1919–1939. J Imperial Commonw History 47(4):773–799. https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2019.1596203

Lees GR (1905) Village life in Palestine: a description of the Religion, Home Life, Manners, Customs, characteristics and superstitions of the peasants of the Holy Land, with reference to the Bible. Longmans, Green

Little MA (2015) Pastoralism. Basics in Human Evolution, 337–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-802652-6.00024-4

Nadan A (2006) The Palestinian Peasant Economy under the Mandate. Harvard University Press

Namdar L & Sapir-Hen, L. (in press). Zooarchaeological Report. In Gross B (ed), Salvage excavations in Beth-Shemesh East. Salvage Excavation Reports. Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University

Namdar, L., and Sapir-Hen, L. 2023. The Faunal Remains from the Islamic Period, Area I. In J. Zimni (Ed.),Urbanism in Jerusalem from the Iron Age to the Medieval Period at the Example of the DEI Excavations on MountZion (pp. 826–863). University of Wuppertal

Namdar L, Gadot Y, Mavronanos G, Gross B, Sapir-hen L (2022) Frozen in time: Caprine Pen from an early islamic earthquake Complex in Tel Beth Shemesh. J Archaeol Science: Rep 45:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2022.103555

Namdar, L., Zimni, J., Lernau, O., Vieweger, D., Gadot, Y., and Sapir- Hen, L. 2024. Identifying Cultural Habits andEconomical Preferences Islamic Period, Mount Zion, Jerusalem. Journal of Islamic Archaeology 10.2: 177–197

Redding RW (1984) Theoretical determinants of a herder’s decisions: modeling variation in the sheep/goat ratio. In: Clutton-Brock J, Grigson C (eds) Animals and archaeology. Early herders and their flocks, vol 3. Oxford University Press, pp 223–242

Roza I-E (2006) Mandated landscape: British imperial rule in Palestine, 1929–1948. Routledge

Tchernov E, Horwitz LK (1990) Herd manangement in the past and its impact on the landscape of the southern Levant. In S. Bottema, G. Entjes-Nieborg, & W. Van Zeist (Eds.), Man’s Role in the Shaping of the Eastern Mediterranean Landscape (pp. 207–216). Rotterdam

Waters-Bayer A, Bayer W (1992) The role of livestock in the rural economy. Nomadic Peoples 31:3–18

Weber KT, Horst S (2011) Desertification and livestock grazing: the roles of sedentarization, mobility and rest. Pastoralism:Research PolicyandPractice 1(19):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/2041-7136-1-19

Zeder MA (1991) Feeding cities: specialized animal economy in the ancient Near East. Smithsonian Institution

Acknowledgements

This study began as part of the seminar ‘Palestinian Fellahin: Material and Historical Perspectives’, taught at the ‘Zvi-Yavetz School of Historical Studies’, Tel-Aviv University. For that, we would like to thank Dr. Amos Nadan and Dr. Ido Wachtel, from Tel Aviv University. We would like to thank Prof. Israel Finkelstein for sharing with us the ‘Livestock Enumeration’ documents, and Dr. Roy Marom for sharing with us his knowledge.

Funding

This work is part of the corresponding author’s Ph.D. dissertation ‘Historical Zooarchaeology of the Shephelah and Judean Hills under the Islamic Rule: Villages and Urban Centers’ Economy and Trade Relations’, funded by the Rotenshtrich Foundation and by the Chaim Rosenberg School of Jewish Studies and Archaeology, Tel Aviv University.

Open access funding provided by Tel Aviv University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Linoy Namdar is the leading researcher, who analyzed the material, prepared the figures, and wrote the article as part of her Ph.D. dissertation. Lidar Sapir-Hen and Yuval Gadot are the Ph.D. supervisors, who reviewed the manuscript and participated in the historical and zooarchaeological studies.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Namdar, L., Gadot, Y. & Sapir-Hen, L. Between cities and villages: the livestock economy in historical Palestine. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 16, 105 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-024-02012-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-024-02012-6