Abstract

The Iron Age in continental Europe is a period of profound cultural and biological importance with heterogeneous trends through space and time. Regional overviews are therefore useful for better understanding the main cultural and biological patterns characterizing this period across the European regions. For the area of modern Switzerland, a rich archeological and anthropological record represents the Late Iron Age. However, no review of the main anthropological and funerary patterns for this period is available to date. Here we assess the available demographic, paleopathological, funerary, and isotopic data for the Late Iron Age in the Swiss territory, and summarize the cultural and biological patterns emerging from the available literature. Finally, we highlight a series of research avenues for future studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Late Iron Age in Switzerland: an overview

Normally defined as the time between the eighth century BCE and the territorial spread of the Roman Empire (Table 1), the Iron Age in Continental Europe featured important biocultural changes (Champion et al. 2016; Kruta 2009; Müller et al. 1999; Vitali 2004, 2011; Wells 2011).

These included profound social, economic, and political innovations, as well as the development of distinctive forms of artistic expression (Champion et al. 2016; Müller et al. 1999; Müller and Lüscher 2004; Stöckli 2016; Wells 2020). The establishment and development of networks between different regions and cultures led to a substantial flow of ideas and people, a pattern that anticipates the Roman Empire biocultural mosaic. Although featuring important cultural similarities across regions, the Iron Age was also characterized by marked socioeconomic and biocultural heterogeneity with effects on human lifestyle and biology (Kruta 2009; Laffranchi et al. 2019; Laffranchi et al. 2016; Moghaddam et al. 2016; Moghaddam et al. 2018; Scheeres et al. 2014; Wells 2011). We need a contextualized overview of these processes when we try to evaluate the biocultural relevance of the Iron Age and its relationships with preceding and subsequent periods, namely the Bronze Age and Roman Times.

In today’s Switzerland, the first archaeological traces of a settlement attributable to the Early Iron Age date to ca. 800 BCE. This is the case, for example, at Weiler Frasses, near the Lake Neuchâtel (Müller et al. 1999). The Roman occupation of Swiss territories started around 200 BCE in the southern region of Ticino, followed by the southwestern region of Geneva around 55 BCE. Following the Alpine campaign of 15 BCE and up to the fifth century CE, the area of today’s Switzerland was firmly part of the Roman Empire (Müller et al. 1999; Tarpin et al. 2002). The Swiss Iron Age includes an earlier and a later phase (Champion et al. 2016; Kaenel 1999): The Early Iron Age, or Hallstatt period, named after the village Hallstatt in Austria, dates from about 800 to 450 BCE. The Late Iron Age or La Tène period is named after the archeological site at Lake Neuchâtel in Switzerland and dates from about 450 to 15 BCE (Cunliffe 1997).

Archeological sites from the La Tène period, including settlements, oppida, cemeteries, and sanctuaries, are numerous in Switzerland (Müller and Lüscher 2004). Given the specific focus of this work, we present in the following overview only funerary contexts for which anthropological results have been published. For more archeologically oriented syntheses, we refer the reader elsewhere (Kaenel 1999; Müller et al. 1999; Müller and Lüscher 2004).

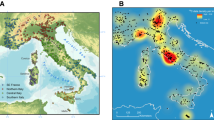

Figure 1 illustrates the geographic distribution of the mentioned contexts.

Only few human remains are preserved from sites in eastern and central Switzerland. In the northeast of the Swiss Plateau in the canton of Zürich, the Andelfingen cemetery probably belonged to a later oppidum (Viollier 1912), while isolated graves and small groups were also found (Altorfer and Schmid 1996; Fischer 1994; Horisberger 2019).

The Basel-Gasfabrik site in northern Switzerland, an unfortified proto-urban settlement with two necropolises, was discovered in 1911 and has been under research since (Hüglin and Spichtig 2010; Jud and Spichtig 1998; Knipper et al. 2017, 2018; Pichler et al. 2015; Pichler et al. 2013; Pichler et al. 2014; Rissanen et al. 2013; Schaer and Stopp 2005; Trancik Petitpierre 1996). Both necropolises yielded a total of almost 200 individuals, but it is assumed that many more graves were destroyed during earlier construction without archeological surveillance. Between 2005 and 2007, excavations took place in both necropolises during which 42 skeletons were documented. Human remains were found not only in the two cemeteries, but also within various settlement features (Pichler et al. 2015; Pichler et al. 2013).

In total, eight Late Iron Age sites are known around Luzern in central Switzerland (Nielsen 2014), but human remains are only preserved from few (Lehner 1986; Moghaddam et al. 2013a, 2013b; Nielsen 2014).

Southern Switzerland (cantons of Grisons, Ticino, and Valais) contains many sites (Kaenel 1999); in Grisons, human remains from two sites are preserved. The cemetery in Trun-Darvella at the Rhine headwaters may have belonged to a settlement nearby. Among the grave goods, lances, swords, and costume objects were found (Tanner 1980). The human remains were not preserved and/or collected systematically at the sites in Castaneda (Keller-Tarnuzzer 1933; Nagy 2000; Nagy 2008) and Cama (Reitmaier 2020). In the canton of Ticino, large Celtic cemeteries existed along important trade routes between the southern Alpine valleys and Raetia (e.g., Giubasco or Arbedo), but most were excavated around 1900 and bones were not collected. Due to the characteristics of the soil, only very few human remains from this area are preserved (Costa 2005; Del Fattore 2007). A great number of Late Iron Age burials in the canton of Valais were destroyed by farming activities during the nineteenth century. In the last decades, several sites in and around Sion were excavated professionally and have been subject to comprehensive research. They include assemblages of mostly well-preserved burials in Sion-Sous-le-Scex, some of which were equipped with costume objects and weapons and in Bramois, only 3 km away. It is assumed that a settlement was located nearby or that rituals were performed there (Curdy et al. 2009; Debard 2014). Several more burials were found at various locations in Sion and in Randogne (Curdy et al. 2009; Debard 2014; Hofstetter 2018; Moret et al. 2000).

The highest concentration of graves was discovered in the canton of Bern, in the Swiss midlands. Geographical clusters of findings suggest two centers: one around the Belp Mountain, the other around the Enge Peninsula where the Celtic oppidum “Brenodor,” a proto-urban settlement on the territory of today’s federal capital of Bern, was located. This was the focal point of burials nearby (Jud and Ulrich-Bochsler 2014). The largest cemetery is Münsingen-Rain with originally 220 burials (Hodson 1968; Müller 1998; Müller et al. 1999; Wiedmer-Stern 1908). The Aare valley between the city of Bern and Lake Thun seems to have been part of a fairly developed settlement area in the Late Iron Age (Müller 1996).

Important sites like the eponymous La Tène and Cornaux-Les Sauges in the canton of Neuchâtel comprised skeletal findings from the La Thielle River that were associated with objects like vehicle parts, swords, lances, and shields (Kaenel 2007; Müller 2002; Müller et al. 1999; Schwab 1989). Most human remains from the canton of Fribourg are from the cemeteries at Gumefens (Jud 2009), Gempenach (Kaenel and Favre 1983), and Kerzers (Ramseyer 1997). The two cemeteries in Gumefens contained a high proportion of burials with weapons and richly equipped female burials that suggested a high social status of the individuals buried there (Jud 2009).

Noteworthy concentrations of graves in western Switzerland in the cantons of Vaud and Geneva are located along Lake Geneva (Kaenel 1990, 1995; Maroelli and Gallay 2014). Other human remains in this area were found at sites that are interpreted as sanctuaries (Bonnet et al. 1989; Dietrich et al. 2007, 2009a, b; Haldimann and Moinat 1999; Moinat 1993; Simon and Desideri 1999).

As mentioned, detailed anthropological analyses have been performed only for some Iron Age skeletal remains from the Swiss territory. The results of these investigations are often difficult to access due to their publication in local archeological magazines/gazettes in German, French, or Italian language. These works are moreover typically focused on single contexts. To date, a synthesis of the anthropological data for this period and geographic area is still missing, and a comparison with preceding and later chronological phases is absent. This hampers the reconstruction of a larger picture and the exploration for common or diverging patterns (e.g., in demography, life quality, diet, funerary rituals).

Based on these premises, our study aims to review and synthesize the available anthropological data for the Late Iron Age in Switzerland according to a suite of topics. These include (1) the relative representation of skeletal remains; (2) the variability of funerary contexts and funerary rituals; (3) main demographic patterns; (4) paleopathological patterns; (5) paleodietary and paleomobility reconstructions.

Material and methods

We first screened all available anthropological reports for late Iron Age (ca. 4th–1st centuries BCE) contexts from the Swiss territory. We then excluded all contexts without inhumations (e.g., incinerations) and those lacking the minimal anthropological assessment of age-at-death and sex for at least part of the individuals. The final dataset includes 474 individuals from 75 archeological sites covering 12 cantons. The number of individuals from each context ranges from 1 to 76 (Table 2).

The variables considered in our review include representation/preservation of human remains, types of funerary treatment, demographic patterns (sex, age at death), paleopathology (dental caries, cribra orbitalia, trauma), and data from stable isotope ratio studies.

When discussing demographic patterns, we followed the age class subdivision commonly adopted by Swiss anthropological reports: infans I (0–7 years old), infans II (7–14 years old), juvenile (14–20 years old), adult (40–60 years old), mature (40–60 years old), senile (≥ 60 years old).

Our choice of focusing on cribra orbitalia, dental caries, and trauma was dictated by the amount and quality of available data. Little paleopathological research has been conducted using skeletal material from the La Tène period in Switzerland (Curdy et al. 2009; Gallay 2014; Laffranchi et al. 2021; Moghaddam et al. 2013a, b; Moghaddam et al. 2015; Ramseier et al. 2005). In this regard, systematic and epidemiological studies are especially rare.

Cribra orbitalia is thought to be associated with iron deficiency anemia. Various factors can contribute to the formation of Cribra orbitalia, particularly not only parasitic infestation and infectious diseases and diarrheal diseases but also malnutrition or changes in diet (Hengen 1971; Mensforth et al. 1978; Reinhard 1992; Stuart-Macadam 1982, 1987a, 1987b; Stuart-Macadam 1989a, b; Stuart-Macadam 1989a, b; Stuart-Macadam and Kent 1992; Wadsworth 1992; Weinberg 1992). Vitamin C deficiency (Grupe 1995), vitamin B12 or folic acid deficiency (Walker et al. 2009), inflammation, and hemorrhagic processes (Carli-Thiele and Schultz 1999) have also been discussed as causes of Cribra orbitalia.

Carbohydrates (sugars and starches) play a major role in the development of dental caries. Plaque pH falls within minutes after administration of sugar, and, to a lesser degree, starches. Frequent sugar consumption and foods with both sugars and starches are highly cariogenic (Hillson 1996). An examination of dental caries can therefore be used to assess dietary patterns.

For the study of postcranial trauma, we compiled a dataset from the regular burial sites for which paleopathological data was published in sufficient detail and which contained complete skeletons rather than only skulls. We added the specimens of Münsingen-Rain to the aforementioned subsample for the study of cranial trauma.

Stable isotope ratios of carbon and nitrogen (δ13C, δ15N) are often used in archeology for reconstructing past dietary patterns (e.g., dietary contribution of C3 vs. C4 plants, access to animal proteins, exploitation of terrestrial vs. marine vs. freshwater resources) (Katzenberg 2007; Schoeninger 2011). Isotopic ratios of oxygen and strontium (δ18O, 87Sr/86Sr), and, less frequently, sulfur (δ34S) are usually explored for detecting patterns of regional nonlocality and mobility (Lightfoot and O'Connell 2016; Montgomery 2010). In this work, we include an overview of this type of studies for the Swiss territory, in order to highlight the possible presence of main tendencies for this geographic and chronological context.

For some sites, anthropological data are listed in unpublished or preliminary reports (Dietrich et al. 2007, 2009a, b; Maroelli and Gallay 2014; Moinat 2009). In other instances, only scarce information is available due to the extremely poor preservation of the skeletal remains (Costa 2005; Del Fattore 2007; Kaenel 1990; Moghaddam 2016). We decided not to include these cases in our summary statistics but rather to consider them only when discussing our data. For the same reason, we did not attempt an exploration of fine-grained chronological or regional patterns in our dataset, but focused on single archeological and anthropological variables and explored these using all contexts and individuals for which the relevant data was available.

Finally, in order to provide a broader contextualization to our results, we collected a comparative dataset based on the same criteria followed for the Iron Age including 71 funerary contexts from the Swiss territory and chronologically spanning from the Neolithic (ca. 6500–2200 BCE) to the post-medieval period (ca. 16th–19th century CE) (Table 3).

A word for the wise: we are fully aware of the pitfalls associated with grouping data of varying quantity and quality, contexts from a fairly large region and timespan as well as from different types of archeological settings in the same study. However, we also believe that the results from such an approach, if considered critically, have the potential to shed some light on a larger picture (especially regarding potential demographic and broad chronological aspects) otherwise “buried” in the often difficult to find specialist reports and/or case studies (cf. Alterauge et al. 2020; Milella et al. 2015; Moghaddam and Lösch 2015).

This, in conjunction with the bibliography collected by our study, may provide a useful—although necessarily rough—basis for better defining open research questions to address by further, more detailed analyses.

Results

Representation of the remains

In the selected sample of sites, roughly three-quarters of the skeletons which were originally present were not preserved or not stored (Table 4).

The true proportion is most likely even much higher because only sites with preserved human remains and published anthropological results were considered in this study. For example, Kaenel (1990) listed a total of 232 grave inventories from Western Switzerland, but anthropological data were available for only 8 of them (3.4%). Altogether, we assume that bones were preserved and/or collected from less than 10% of all excavated graves.

Funerary rites: cemeteries and isolated graves

In the Early Iron Age (Hallstatt period), the dead were buried inside tumuli. Most were cremated, but during this period a shift took place and inhumations appeared alongside cremations. In Western Switzerland, the new custom began earlier than in Eastern and Southern Switzerland, where cremations continued for longer. At the beginning of the La Tène period, the custom of cremating the dead was completely replaced by inhumations in a gradual process (Lüscher and Müller 1999). In LT A, several inhumations still took place in older tumuli from the Hallstatt period, for example in Orny-sous-Mormont (Maroelli and Gallay 2014) or Murten-Löwenberg (Kaenel 1990), but generally the La Tène period is characterized by inhumations in flat graves (Kaenel 1990; Lüscher and Müller 1999).

Different types of grave constructions have been identified, including grave chambers or rows of stones, and stones covering graves that are thought to have originally been placed on a coffin lid. Coffins were made from boards or hollowed tree trunks. Female graves often contain sets of jewelry and fibulas, whereas men were sometimes interred with arms such as swords and lances (Lüscher and Müller 1999). Another shift occurred towards the end of the Late Iron Age, when the cremation of the dead reappeared around 150 BCE and consequently became established again (Müller and Lüscher 2004; Ruffieux et al. 2006; Suter et al. 1990).

The orientation has been reported for 34 sites and 446 individuals in our sample (Fig. 2, Table 5).

These include all burials from Münsingen-Rain (Hodson 1968), even though human remains are only preserved from a fraction of these graves. For the other sites, we considered only the orientations of those individuals for which anthropological data exists as well. The graves were predominantly oriented on the N-S (head in the north, feet in the south) or S–N axis. Less than a quarter of all graves were oriented towards the East or the West. Altogether, more than half of the graves faced the south, southwest, or southeast (53%), while another 28% faced the north, northeast, or northwest. Only 19% were oriented towards the east or the west.

Funerary rites: “irregular” burials

A number of sites yielded unusual burials, including complete and partial skeletons in pits in settlements and sanctuaries, skeletons in a seated/hyperflexed position, and human remains in rivers and lakes. For the sake of simplicity, we grouped them together even though their interpretations may vary.

During an excavation from 2006 to 2009 on the hill of La Sarraz-Le Mormont, an alleged Celtic sanctuary, a surface of more than 8000 m2 with about 260 pits was excavated. The pits contained depositions of offerings which comprised various metal objects, jewellery, millstones, ceramics, tools, coins, and animals. Human remains were also found in the pits (Dietrich et al. 2007, 2009a, b). They comprised complete skeletons as well as isolated bones and body parts. Some of the complete skeletons were found extended supine or prone, others were hyperflexed, and in some cases, the position of the limbs suggested a sitting posture. Some individuals appeared to have been carelessly thrown into the pits. Traces of various types of manipulation were identified on the bones. These were consistent with a large range of actions including exposition to fire, and severing of heads and other body parts as well as evisceration (Moinat 2009).

Individuals buried in a seated or hyperflexed position are also known from Avenches and Geneva (Bonnet et al. 1989; Moinat 1993). The interpretation of these burials is uncertain, but a cultic background is suspected.

The remains of 50–100 individuals were recovered from the La Thielle River in La Tène until the completion of the excavations in 1917. Most bones have since been lost. Some of the preserved long bones were gnawed by carnivores, indicating that the individuals had been at the surface for some time before being deposited in the river (Alt and Jud 2009). The circumstances of the death and the deposition of these individuals in the river are disputed. The abundance of arms at the site suggested a battle background and the human remains have been interpreted as trophies that were attached to the bridge (Müller 2009). However, the demographic composition with children, women, and men, the absence of typical war-related injuries, and instead the presence of suspected traces of post-mortem manipulations, may rather be indicative of human sacrifices, though it cannot be excluded that the individuals were captured non-combatants (Alt et al. 2007). It has also been stated that these findings are to be seen in connection with manipulations of the deceased that are increasingly known from funerary contexts as well and could be considered as exceptional funerary practices rather than human sacrifices (Alt and Jud 2009; Jud 2007).

In close proximity to La Tène, more human remains were discovered in a river bed in proximity to the Iron Age bridge of Cornaux-Les Sauges. The complete skeletons were found in random positions, and in some cases among and under pales from the original bridge. Originally, this site was thought to be a sanctuary (Müller et al. 1999; Müller and Lüscher 2004; Wyss et al. 2002). After a re-examination, Ramseyer (2009) interpreted the findings to be more consistent with the collapse of the bridge, possibly as a result of a large group of people crossing it.

Commingled remains, especially skulls, of at least 21 individuals were recovered from the Celtic port in Geneva. They comprised not only mainly young adults, both male and female, but also children and have been interpreted by Bonnet et al. (1989) as human sacrifices on the basis of the demographic composition, numerous peri-mortem traumas, and/or manipulations and the fact that they did not appear to have been deposited simultaneously but over a longer period of time. These data contradict the fact that they were victims of a single massacre or battle.

The two necropolises of the unfortified proto-urban settlement in Basel-Gasfabrik site yielded a total of almost 200 individuals, but additional skeletal remains representing a minimum number of 130 individuals have been found within the settlement. These comprise 28 complete skeletons from pits and wells and isolated bones from various contexts. Unlike the skeletons in the cemeteries, about 15% of the isolated bones from the settlement showed signs of various peri- and postmortem manipulations that included signs of scorching, as well as various sharp force traumas. Bones from pits in the settlement have been interpreted as relicts of multi-level funerary rites (Pichler et al. 2013).

Demographic patterns

Information about age-at-death and sex are available for 478 individuals from 75 sites. Of these, 363 (75.9%) are adults and 115 (24.1%) are nonadults. The adults include 143 females (39.4%), 164 males (45.2%), and 56 individuals of undetermined sex (15.4%). The nonadults include 67 infans I (of which 10 are neonates), 23 infans II, and 17 juveniles (Table 6).

To better contextualize the demographic composition of the La Tène sample, we compare it with summary statistics from other time periods (Table 7, Fig. 3) and furthermore differentiate between regular and irregular contexts (Fig. 4).

Paleopathology

Cribra orbitalia

The prevalence of Cribra orbitalia has been reported for sites in the cantons of Bern and Luzern (Moghaddam 2016), Basel (Pichler et al. 2015), and Vaud and Valais (Debard 2014) (Table 8).

For the following considerations, only the data from the cantons of Bern and Luzern (Moghaddam 2016) are used because it could be ascertained that they were recorded in a manner consistent with the reference groups in that only individuals with at least one preserved orbit were considered. Compared to the medieval and post-medieval samples, the prevalence of Cribra orbitalia in the Late Iron Age is low in children, whereas the adult prevalence does not stand out (Fig. 5). However, the sample size for children is very small and even the seemingly large difference between Late Iron Age and early medieval children is not statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test P = 0.0797). Suitable reference data from other prehistoric periods in Switzerland is not available to date.

Dental caries

Caries prevalence by tooth has been calculated for the sites from the canton of Bern (Moghaddam 2016). In adults, 79/1468 teeth were found to exhibit carious lesions and the total prevalence is therefore 5.4%. We chose the reference groups only from this canton as well for the purpose of methodological consistency, and to avoid a bias due to possible regional differences (Table 9). In comparison to sites from later periods, the caries prevalence is very low in the Late Iron Age. It is consistent with the values from the Bronze Age and Antiquity, but only one individual represents the latter. Altogether, the prehistoric groups appear to have a similar prevalence of caries. A sharp increase only occurs during the Middle Ages.

Trauma

Regular burials

Fractures were reported in seven adult individuals, three of which were female. In four cases, a long bone was affected (2 clavicles, 1 forearm, 1 tibia). The remaining cases were fractures of hand or foot bones and ribs. All postcranial traumata were healed, and all are consistent with an accidental cause (Galloway 2014a, b).

Cranial trauma was identified in 9 out of 231 individuals (1 female and 8 males, all adult) (Table 10). The traumata affected the mandible in three cases and the cranial vault in the remaining six cases. A male from Kerzers exhibited a lethal injury to the back of his head (Ramseyer 1997) but all other traumata were healed. Because no details about the types of traumata were published, we cannot make a statement about whether they more likely resulted from interpersonal violence or accidents.

Irregular burials

Only one case of postcranial trauma was reported from irregular contexts (an individual from Avenches featuring a distal facture of the humerus with a pseudoarthrosis formed in the process of healing). All other traces of trauma at these sites were identified on cranial bones. They represent 39 individuals of which 17 (43.6%) showed traumatic lesions (Fig. 6, Table 11).

Two individuals with signs of trauma were recovered from a pit in the settlement at Basel-Gasfabrik. A young man had been buried prone with his feet cut off and deposited at the upper body. The second individual, also a male, was located partly under the first and exhibited an injury to the skull (Pichler et al. 2013).

The commingled remains from the Celtic port of Geneva comprise mainly cranial bones of not only young adults (males and females in similar proportions) but also subadults. Peri-mortem trauma was found on a large proportion of the cranial bones (10/21 individuals). The lesions were attributed to sharp force, suspected arrow injuries, fractured condyles and mastoids, and possible decapitations (Bonnet et al. 1989).

Out of 16 skulls from the river in La Tène, seven exhibited lesions, but the cause was only narrowed down in three cases. Individual 1, a male, was decapitated by several violent sharp blows that severed a part of the cranial base. It is suspected that this may have taken place post-mortem. Seven sharp force injuries were found on the skull of individual 5 (male). They are mainly located on the frontal bone and appear to have been inflicted from the same angle. This indicates that they were most likely delivered to an immobilized person and were therefore more likely inflicted post-mortem. The third individual (undetermined sex) had two severe blunt force injuries at the back of the skull, which were interpreted as the cause of death (Alt and Jud 2007, 2009; Alt et al. 2007).

Some skulls from the river at the site of a Celtic bridge in Cornaux-Les Sauges showed blunt force injuries which Ramseyer (2009) thought to be consistent with a blow from being hit by a pale during the alleged collapse of the bridge. No clear indication of interpersonal violence was found in these individuals.

In one skull from La Sarraz-Le Mormont, the mandible was missing but the cervical vertebrae were found in correct anatomical position. Cutting marks indicated that the mandible was removed before the skull was deposited in a pit (Dietrich et al. 2007). One possible explanation is that this was a battle trophy. Historical texts as well as archeological findings suggest that the heads of fallen enemies were cut off and kept by the Gaulois. Trophies are said to have been attached to the horses’ necks, nailed to houses, or embalmed and kept in cases (Dietrich et al. 2007).

Isotopic data on diet and mobility

The last decade has seen a sharp increase of isotopic reconstructions of diet and mobility in Swiss archeological contexts dating to the Iron Age. Published data are available mainly for the Southern, Central, and Northern regions. Overall, isotopic data point to these populations having a mixed diet including both plants and animal (especially terrestrial) proteins and to the exploitation of both C3 and (to a lesser extent) C4 plants (Bucher et al. 2019; Knipper et al. 2014; Moghaddam et al. 2016; Moghaddam et al. 2018). Regional differences separate the Alpine regions from the Swiss Plateau, with the population inhabiting the latter featuring a diet with a higher contribution of C4 plants (likely millet) and animal proteins (Moghaddam et al. 2018).

Sex-related dietary differences have been detected at Münsingen-Rain, where males consumed more meat and/or dairy products than females, especially those individuals who had been buried with weapons (Moghaddam et al. 2016). Conversely, at Basel-Gasfabrik, the diets of males and females did not differ significantly (Knipper et al. 2017), and no straightforward relationships was found between isotopic and mortuary data.

Currently, regional mobility has been investigated only at two Iron Age sites: Münsingen-Rain (Hauschild et al. 2013; Moghaddam et al. 2016) and Basel-Gasfabrik (Knipper et al. 2018). Results suggest a frequency of nonlocals between 10 and 14.7% at Münsingen with no specific sex distribution. A different situation is represented by Basel-Gasfabrik, where the nonlocal individuals reach a frequency of 37% and include especially females.

Discussion

Representation

Many Late Iron Age sites were discovered and excavated in the nineteenth or early twentieth century. At this time, human remains were not a research and collection priority. Therefore, large numbers of skeletons were neither documented nor kept, while others were too poorly preserved for any statements to be made (Kaenel 1999). Even when human remains were collected during early excavations, generally only selected skeletal elements were kept. When the number of preserved skeletons is compared to the number of burials that were originally present and are known for some sites, it becomes evident that thousands of skeletons must have been destroyed or were not collected during early excavations.

As mentioned above, most Late Iron Age sites in Switzerland, and thus also the human remains, are concentrated around a few centers. It can be speculated to which degree this illustrates the actual situation in the Late Iron Age. At least partly, these concentrations may reflect areas of more intense archeological research both in the past and present.

Funerary rites

In sum, while individual burials in cemeteries are generally considered the “normal” and by far most common case, this idea might have to be challenged for the Late Iron Age. Indeed, the variegated handling of the dead is a striking characteristic of the La Tène period, in the Swiss territory, and elsewhere in Europe. Like for the Swiss findings, several different interpretations for such “irregular” contexts have been discussed for sites in Austria, France, and Germany depending on their characteristics (Brunaux and Malagoli 2003; Hahn 1999; Lange 1995; Pichler et al. 2013; Teschler-Nicola 2017). They include multi-level funerary rites that may have included de-fleshing or exposure of corpses to birds and other animals, sacrifices and other ritual practices, and trophy hunting.

The interpretation of the human remains from the “irregular” contexts presented in this work is challenging in some cases because of the early and undocumented excavations. The completion of the ongoing work on skeletons and isolated bones from La Sarraz-Le Mormont and Basel-Gasfabrik holds potential for advancing the understanding of the funerary rites in contexts other than cemeteries.

Demographic patterns

The high proportions of nonadults in Neolithic, Bronze Age, and High/Late Medieval contexts fit expectations for pre-modern attritional demographic profiles (Chamberlain 2006).

The La Tène, Roman, and Early medieval samples deviate from this trend and show a clear underrepresentation of nonadults. Excluding a low infant mortality for these periods (an explanation not supported by available archeological and historical data), we can try to isolate other factors responsible for this apparent demographic anomaly.

In Switzerland, only few neonate and infant skeletons were found in Roman necropolises, but hundreds have been excavated in settlement contexts (Grezet 2020; Kramis and Trancik 2014). This would correct the biased demographic profile from the necropolises used in this study and is consistent with what is known from classic sources (e.g., Cicero—De Legibus 2, 58; Juvenal—Saturae 15, 139; Fulgentius—Sermones Antiqui 7; Plinius—Naturalis Historia 7, 72), according to which children up to ca. 40 days old—or before they teethed—were not cremated but buried intra muros.

The demographic profile of the Roman period closely resembles that of early medieval samples. The underrepresentation of small children, especially neonates and small infants, in early medieval cemeteries (“Kleinkinderdefizit”) is a well-known phenomenon and has been discussed by many authors (Lohrke 2002). It is usually explained as the result of selective funerary practices (in particular, separate burial places for unbaptized children), and/or the effect of taphonomic and excavation-related damage to the fragile skeletal remains of the younger subadults. Early medieval settlements have hardly been excavated in Switzerland. This opens the intriguing possibility that during this period young subadults may also have been buried in domestic contexts. It has been hypothesized that the Roman custom of burying neonates in settlements may have its roots in the Iron Age (Langenegger 1996). Indeed, neonates have been found in Early Iron Age settlements in Brig-Glis/Waldmatte (Curdy et al. 1993) and in Lausanne (Langenegger 1996). Evidence exists from the Late Iron Age as well. The recent excavations at Basel-Gasfabrik have brought to light large numbers of neonate and infant skeletons in both the cemeteries and the settlement area (Pichler et al. 2015; Pichler et al. 2013; Rissanen et al. 2013). Altogether, the deficit of small children in the La Tène sample is reflected in the Roman and early medieval samples. Burials of small children in the settlement area at Basel-Gasfabrik give further weight to the theory of a special funerary treatment in the La Tène period, and the completion of the work on this site will possibly shed more light on this. Altogether, the findings suggest a possible continuity over centuries in the special funerary treatment of neonates and small infants, even though the beliefs behind the custom changed over time.

When attempting to interpret the results, several factors must however be kept in mind. Firstly, we considered only inhumations in this study, but in some periods, cremation was predominant (Late Bronze Age, Early Iron Age, and Antiquity). This leads to small sample sizes as well as a possible bias if selection mechanisms were applied with regard to the individuals who were either cremated or inhumated. Especially the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age are practically not represented in our sample.

Excavation-related factors could also be partly responsible for the deficit of the youngest age group. It is noteworthy that the neonate skeletons in the La Tène sample were found at sites that were excavated after the second half of the twentieth century. Since the human remains were generally not paid much attention to during early excavations, it is possible that they were overlooked, especially if no grave goods were associated with them. The numerous neonate skeletons in settlements from the Antiquity were all discovered in more recent excavations from the 1980s onward as well, owing to more refined excavation methods (Kramis and Trancik 2014). Large numbers of fetal, neonate, and infant bones at Basel-Gasfabrik were discovered only during the archeozoological analyses and had apparently not been recognized during the excavation (Pichler et al. 2013; Rissanen et al. 2013). Altogether, these findings suggest that the underrepresentation of children in the La Tène sample is strongly influenced by excavation-related factors besides possible selective funerary customs.

Regarding the possible relationship between demography and type of deposition, it is interesting to note that the sex ratio in irregular burials strongly deviates from that of “formal” funerary areas. Specifically, whereas the latter include an equal proportion of males and females (both 50% of sexed individuals), the proportion of the two sexes in irregular contexts is quite unbalanced (females 4.9%, males 39.3%). Even considering that a large number of individuals could not be assigned to a sex (39.3%), it is unlikely that this difference is purely due to chance. Age-wise, subadults are more frequent in regular (25.2%) than in irregular contexts (16.4%).

The findings in Switzerland suggest a selection mechanism (or several) that favored adult males for burial in irregular contexts. Similar observations have been reported from e.g. Austria (Teschler-Nicola 2017). Although the meaning of these contexts is not clarified, the high proportion of adult males may suggest a link to a high status of the deceased. Special offerings have often been found to be associated with such burials, e.g., in Basel-Gasfabrik and La Sarraz-Le Mormont (Dietrich et al. 2007; Hüglin and Spichtig 2010; Schaer and Stopp 2005). There are also clues from isotopic studies that suggested a possible higher social status of men (Moghaddam et al. 2016). Warfare events and associated trophy hunting may be another background of this observation (Hofeneder 2005; Müller 2009).

Paleopathology

The observed adult prevalence of Cribra orbitalia is consistent with findings in later periods. A higher prevalence in children than in adults is also characteristic. The latter is due to Cribra orbitalia primarily reflecting stress phases in childhood and due to the fact that the lesions can remodel during adulthood. The conditions leading to these lesions have a negative impact on survivorship (Lewis 2007; Mittler and Van Gerven 1994; Papathanasiou et al. 2018). However, far-reaching conclusions about the living conditions can hardly be drawn based on such a small sample.

Our data suggest that highly cariogenic foods were not a major part of the diet during the La Tène period. While analyses of stable isotope ratios showed that the C3 plant-based diet might have been high in carbohydrates, it appears that it was not highly cariogenic, possibly because of low sugar content and infrequent meals. Moreover, the pronounced occlusal attrition observable for this period suggests abrasive foods, which could have had a natural cleaning effect and removed fissure caries. Groups with high attrition rates generally have low caries rates, even though the relationship between the two is not entirely clear (Hillson 1996).

The examination of traumata reveals clear differences between “regular” and “irregular” burials despite the difficulties arising from commingled remains and a lack of detail given in the original reports. Postcranial fractures that were most likely the result of falls and other accidents were found in both contexts. They affected males and females in similar proportions and were only found in adults. In cemeteries, cranial trauma was found in a small percentage of individuals. The affected individuals were all adult and in all but one case male. The proportion of skulls with traumatic lesions, which were without exception peri-mortem or post-mortem, was much higher in irregular burial sites, and both sexes in adults as well as children were affected. While the cranial traumata in cemeteries were most likely largely due to interpersonal violence, the picture in the sites with irregular burials was more ambiguous because many of the lesions were thought to represent post-mortem manipulations.

Diet and mobility

Published isotopic studies for the Swiss Iron Age are still spatially biased (Knipper et al. 2018; Knipper et al. 2017; Moghaddam et al. 2016; Moghaddam et al. 2018), with the midlands being rather overrepresented. The picture emerging is however rather intriguing and raises several questions for future studies. Three aspects seem to deserve special attention: (a) the presence of regional differences in diet composition, (b) the possible association between social differentiation and diet, and (c) the presence of residential rules shaping mobility patterns.

The available data point to a marked variability across contexts in the relative exploitation of C3 vs. C4 plants, terrestrial vs. freshwater animal food sources, and dietary contribution of animal vs. plant proteins (Knipper et al. 2017; Moghaddam et al. 2016; Moghaddam et al. 2018). These results suggest important cultural, economic, and ecological differences across these “Celtic” populations and, potentially, their variable exposure to the Mediterranean economic sphere (Moghaddam et al. 2018). Strictly related is the type of relationship linking social differentiation and differential access to food resources. A simplistic model would expect high-quality diets for individuals enjoying a privileged social status, based on either status, sex, or a combination of these. We now know that things are actually more complex. This is clearly demonstrated by the diverging results obtained by published comparisons of paleodietary and funerary data (Laffranchi et al. 2019; Le Huray and Schutkowski 2005; Milella et al. 2019). Estimates of social differences based on funerary patterns are notoriously challenging (Parker Pearson 1982, 1993). Isotopic data, moreover, can mask subtle dietary differences of potential social relevance (e.g., the consumption of various cuts of meat and diverse types of animal products). As already mentioned, for the region and time under study, a dietary variability potentially linked to social differences has been highlighted only at Münsingen-Rain (Moghaddam et al. 2016). The fact that the same pattern was not observed in other contexts raises the possibility that on the Swiss territory and during the Late Iron Age, social differences (both vertical and horizontal) were multifaceted, and manifested variably.

A similar variability may also characterize the type of social factors influencing human mobility. The larger frequency of females among nonlocals at Basel-Gasfabrik has been interpreted by Knipper et al. (2018) as the evidence of a patrilocal residential system. Conversely, no such sex bias has been observed at Münsingen-Rain (Moghaddam et al. 2016), where nonlocals are, moreover, less numerous. The actual meanings of these differences are difficult to test, especially given the paucity of contexts whose isotopic data are directly comparable. The social, economic, and political factors behind mobility were likely numerous and intermingled with individual choices, in the past as nowadays (Anthony 1990; Burmeister 2000; De Ligt and Tacoma 2016; Eckardt 2010; Kearney 1986; Lee 1966; Massey et al. 1993).

Conclusion

A review of anthropological, funerary, and biogeochemical data from the Late Iron Age in Switzerland is a challenging undertaking. In addition to the difficulties associated with hardly documented early excavations, incompletely collected skeletons, and poor skeletal preservation, further challenges arise from the quality and quantity of available anthropological data and its manner of publication. Findings are often published in different local languages, in a rather fragmented manner, or in inaccessible journals, and are often limited to age and sex determination. This has begun to change in recent years. Some human remains have been subject to intense anthropological research that has shed light on aspects such as diet and mobility or on selected burials. However, systematic osteological or paleopathological studies are still almost non-existent, and the interpretation of the available results is often hampered by purely descriptive approaches, methodological inconsistencies, and lack of detail in original reports.

Nevertheless, we tried to draw a general picture of the anthropological findings in skeletons from the Late Iron Age and identified aspects worthy of further research. The demographic findings revealed that children are strongly underrepresented in the skeletal record of this period, and the comparison with samples from other periods indicated that this might be the result of different funerary rites (particularly burial in separate locations) for the youngest age groups. Furthermore, differences were found between regular and irregular burial sites, with the latter exhibiting a predominance of adult males but fewer adult females and children.

Regular and irregular burial sites also differed with regard to the prevalence of cranial trauma. In the irregular burial sites, a large proportion of individuals exhibited peri-mortem or post-mortem traumata that were not identified in regular cemeteries.

We identified research potential especially for paleomobility, for which only two sites have been published to date, and for systematic paleopathological studies. The prevalence and patterning of trauma, markers of unspecific stress, and dental pathologies are only some aspects that merit further consideration. Pathological alterations indicative of infectious disease have not been reported for any of the individuals in the sample. This raises the question whether markers of infectious disease were not present or if they were not recorded or were not recognizable due to poor preservation or other factors.

The recent excavations at La Sarraz-Le Mormont and Basel-Gasfabrik, among others, offer the opportunity to study well-documented assemblages, which may greatly enhance the knowledge of the funerary customs in a sanctuary as well as in a settlement and its necropolises.

Availability of data and materials

All data collected are published within this article or in the literature cited.

References

Alt KW, Jud P (2007) Die Menschenknochen aus La Tène und ihre Deutung. La Tène: Die Untersuchung - Die Fragen - Die Deutung. Verlag Museum Schwab, Biel, pp 46–59

Alt KW, Jud P (2009) Les ossements humains de La Tène et leur interprétation. In: Honegger M, Ramseyer D, Kaenel G, Arnold B, Kaeser M-A (eds) Le site de La Tène: bilan des connaissance, état de la question. Hauterive, pp 57–63

Alt KW, Jud P (2013) Die menschlichen Knochen aus La Tène in der Sammlung Schwab. In: Lejars T (ed) La Tène: La collection Schwab (Bienne, Suisse). La Tène, un site, un mythe. Cahiers d’archéologie romande, Lausanne, pp 287–294

Alt KW, Jud P, Betschart M (2007) Die Menschenknochen aus La Tène und ihre Deutung. Archäologie Schweiz 30(3):28–33

Alt KW, Jud P, Müller F, Nicklisch N, Uerpmann A, Vach W (2005) Biologische Verwandtschaft und soziale Struktur im Latènezeitlichen Gräberfeld von Münsingen-Rain. Jahrbuch RGZM 52:157–210

Alterauge A, Meier T, Jungklaus B, Milella M, Lösch S (2020) Between belief and fear - reinterpreting prone burials during the Middle Ages and early modern period in German-speaking Europe. PLoS One 15(8):e023843. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238439

Altorfer K, Schmid P (1996) Ein mittellatènezeitliches Kriegergrab aus Wetzikon ZH. Jahrbuch der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Ur- und Frühgeschichte 79:198–203

Anthony DW (1990) Migration in archeology: the baby and the bathwater. Am Anthropol 92:895–914

Baeriswyl A, Deschler-Erb S, Descoeudres G, Bujard J, Tremblay L, Niffeler U, Reitmaier T (eds) (2020) Archäologie der Zeit von 1350 bis 1850, vol VIII. Verlag Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Ur- und Frühgeschichte, Basel

Bauer I (1996) Fibeln Forscher und vornehme Frauen. Archäologie Schweiz 19(2):80–84

Bay R (1968) Die menschlichen Skelettreste aus dem spätrömischen Gräberfeld von Kaiseraugst. In: Schmid E, Berger L, Bürgin P (eds) Provincialia. Festschrift Für Rudolf Laur-Belart. Stiftung Pro Augusta Raurica, Basel/Stuttgart, pp 6–14

Bleuer E, Doppler T, Fetz H (2012) Neolithische Bestattungsplätze im Kanton Aargau und in angrenzenden Regionen. In: Doppler T (ed) Spreitenbach-Moosweg (Aargau, Schweiz): Ein Kollektivgrab um 2500 v. Chr. Urs Zuber AG, Basel, pp 233–266

Bleuer E, Huber H, Langenegger E (1999) Das endneolithische Kollektivgrab von Spreitenbach im Kanton Aargau. Archäologie der Schweiz 22(3):114–122

Bonnet C, Zoller G, Broillet P, Haldimann M-A, Baud C-A, Kramar C, … Billaud Y (1989) Les premiers ports de Geneve. Archäologie der Schweiz 12(1): 2–24

Brunaux J-L, Malagoli C (2003) La France du Nord (Champagne-Ardenne, Ile-de-France, Nord, Basse-Normandie, Haute-Normandie, Pas-de-Calais, Picardie). In: Arcelin P, Brunaux J-L (eds) Cultes et sanctuaires en France à l’âge du Fer. CNRS Editions, Paris, pp 9–73

Brunner JA (1972) Die frühmittelalterliche Bevölkerung von Bonaduz: Eine anthropologische Untersuchung. Rätisches Museum, Chur

Brunner S (2014) Eine spätrömische Nekropole westlich des Castrum Rauracense: das Gräberfeld Kaiseraugst-Höll. Jahresberichte aus Augst und Kaiseraugst 35:241–331

Bucher J, Eppenberger P, Kühn M, Mee V, Motschi A, Rast-Eicher A, … Zürcher M (2019) Kelte trifft Keltin. Zwei Bestattungen der Mittellatènezeit an der Kernstrasse in Zürich. Jahrbuch Archäologie Schweiz 102:7–44

Burmeister S (2000) Archaeology and migration - approaches to an archaeological proof of migration. Curr Anthropol 41:539–567

Carli-Thiele P, Schultz M (1999) Ätiologie und Epidemiologie der Krankheiten des Kindesalters im Neolithikum. In: Kokabi M, May E (eds) Beiträge zur Archäozoologie und Prähistorischen Anthropologie II. Stuttgart, pp 251–256

Challet V (1997) Les techniques ornementales des bijoutiers celtes de la haute vallée du Rhin aux 4e et 3e siècles av. J. C. Etude des bijoux provenant des nécropoles de Nebringen-Gäufelden (Bade-Wurttemberg) et d’Andelfingen ZH. Jahrbuch der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Ur- und Frühgeschichte 80:111–130

Chamberlain AC (2006) Demography in archaeology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Champion T, Gamble C, Shennan S, Whittle A (2016) Prehistoric Europe. Routledge, Oxon

Christen M-F, Cuendet N (2006) Zahnbefunde der Schädel aus dem früh- bis hochmittelalterlichen Gräberfeld von Oberbüren-„Chilchmatt“ bei Büren an der Aare. Bulletin der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie 12(2):25–46

Cooper C, Fellner R, Heubi O, Maixner F, Zink A, Lösch S (2016) Tuberculosis in early medieval Switzerland - osteological and molecular evidence. Swiss Medical Weekly 146:w14269. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2016.14269

Cooper C, Lösch S, Alterauge A (2017) Anthropologische Untersuchungen zu den Bestattungen aus Bern-Bümpliz, Mauritiuskirche und Bienzgut. Archäologie Bern/archéologie Bernoise 2017:234–245

Cooper C, Rüttimann D, Lösch S, (2016b). Courroux, Place des Mouleurs, (2012) Anthropologischer Bericht. In: Fellner R (ed) Archéologie Cantonale Rapport 2012 vol. 1. Office de la Culture, Porrentruy, pp 77–109

Costa C (2005) La necropoli di Solduno nell’ Età del Ferro. Bolletino Dell’ Associazione Archeologica Ticinese 17:5–11

Cueni A (1995) Die menschlichen Gebeine. In: Descoeudres G, Cueni A, Hesse C, Keck G (eds) Sterben in Schwyz. Beharrung und Wandlung im Totenbrauchtum einer ländlichen Siedlung vom Spätmittelalter bis in die Neuzeit. Schweizerischer Burgenverein, Basel, pp 125–144

Cueni A (2009) Die frühmittelalterlichen Menschen von Aesch (Anthropologische Untersuchungen). In: Hartmann C (ed) Aesch. Ein frühmittelalterliches Gräberfeld. Kantonaler Lehrmittelverlag Luzern, Luzern, pp 83–126

Cunliffe B (1997) The ancient Celts. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Curdy P, Mariéthoz F, Pernet L, Rast-Eicher A (2009) Rituels funéraires chez les Sédunes. Les nécropoles du second âge de fer en valais central (IV.-I. siècle av. J.-C.). Archaeologica Vallesiana 3. Cahiers d'archéologie romande, Lausanne

Curdy P, Mottet M, Nicoud C (1993) Brig-Glis / Waldmatte, un habitat alpin de l’âge du Fer : fouilles archéologiques N9 en Valais. Archäologie der Schweiz 16(4):138–151

De Ligt L, Tacoma LE (eds) (2016) Migration and mobility in the Early Roman Empire. Brill, Leiden

Debard J (2014) Approche bioanthropologique des conditions socio-économiques à la fin de l’âge du Fer en Suisse occidentale: stature, croissance et stress environnemental. Université de Genève, Genève

Debard J, Mariéthoz F, Besse M (2014) A Late Iron Age case of mucopolysaccharidosis in a young adult male from Sion Parking-Remparts (Valais, Switzerland). Paper presented at the 16th Annual Conference of the British Association for Biological Anthropology and Osteoarchaeology, Durham

Del Fattore F (2007) Genti e paesaggi dell’alto Ticino Fra III e II sec. a.C. La necropoli di Tenero-Contra. Rivista Archeologica dell‘Antica Provincia e Diocesi di Como 189:7–42

Dietrich E, Kaenel G, Weidmann D, Jud P, Méniel P, Moinat P (2007) Le sanctuaire helvète du Mormont. Archäologie Schweiz 30(1):2–13

Dietrich E, Méniel P, Moinat P, Nitu C (2009a) Le site helvète du Mormont (Canton de Vaud, Suisse). Résultats de la campagne de 2008. Annuaire d’archéologie Suisse 92:247–251

Dietrich E, Nitu C, Brunetti C (2009b) Les fouilles de 2006 à 2009b et les premières études. In Le Mormont. Un sanctuaire des Helvètes en terre vaudoise vers 100 avant J.-C. Archeodunum, Lausanne, pp 3–4

Doswald C, Kaufmann B, Scheidegger S (1989) Ein neolithisches Doppelhockergrab in Zurzach AG. Archäologie Der Schweiz 12(2):38–44

Drack W (1980) Vier hallstattzeitliche Grabhügel auf dem Homberg bei Kloten ZH. Jahrbuch der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Ur- und Frühgeschichte 63:93–130

Drack W (1992) Das Hallstatt D1-Grab von Lenzburg und verwandte Gräber aus dem nördlichen Schweizer Mittelland. In: Lippert A, Spindler K (eds) Festschrift zum 50jährigen Bestehen des Institutes für Ur- und Frühgeschichte der Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck. Bonn, pp 121–133

Eckardt H (Ed) (2010) Roman diasporas: archaeological approaches to mobility and diversity in the Roman Empire. Journal of Roman Archaeology, Portsmouth

Fischer C (1994) Ein latènezeitliches Körpergrab aus Fällanden ZH-Fröschbach. Jahrbuch der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Ur- und Frühgeschichte 77:139–142

Fischer C (1997) Innovation und Tradition in der Mittel- und Spätbronzezeit. Gräber und Siedlungen in Neftenbach, Fällanden, Dietikon, Pfäffikon und Erlenbach. Fotorotar AG, Zürich/Elgg

Flutsch L, Niffeler U, Rossi F (eds) (2002) Römische Zeit - Età Romana (Vol. V). Verlag Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Ur- und Frühgeschichte, Basel

Gallay A (2014) Une femme associée à des restes de bovins. La fosse 481. Archéothéma, hors-série 7:50

Galloway A (2014a) The lower extremity. In: Wedel VL, Galloway A (eds) Broken bones - anthropological analysis of blunt force trauma, 2nd edn. Charles C Thomas, Springfield, pp 245–313

Galloway A (2014b) The upper extremity. In: Wedel VL, Galloway A (eds) Broken bones - anthropological analysis of blunt force trauma, 2nd edn. Charles C Thomas, Springfield, pp 195–244

Graf M (1993) Ein mittelbronzezeitliches Kriegergrab aus Rafz im Kanton Zürich. Archäologie der Schweiz 16(1):12–16

Grezet C (2020) Vier Neonatenbestattungen auf engstem Raum. Archäologie Schweiz 43(1):47

Grupe G (1995) Zur Ätiologie der Cribra orbitalia: Auswirkungen auf das Aminosäureprofil im Knochenkollagen und Eisengehalt des Knochenminerals. Z Morphol Anthropol 81(1):25–137

Grütter H, Ulrich-Bochsler S (1990) Münsingen, Hintergasse 21. Archäologie im Kanton Bern 1:31–32

Gutscher D, Suter P (1994) Bern, Steigerhubelstrasse/Aseol. Notdokumentation 1993: Latènegrab. Archäologie im Kanton Bern 3:70–72

Hahn E (1999) Zur Bestattungssitte in der Spätlatènezeit. Neue Skelettfunde aus dem Oppidum von Manching. In: Kokabi M, Mai E (eds) Beiträge zur Archäozoologie und Prähistorischen Anthropologie 2. Gesellschaft für Archäozoologie und Prähistorische Anthropologie e.V., Konstanz, pp 137–141

Haldimann M-A, Moinat P (1999) Des hommes et des sacrifices: Aux origins celtiques à Genève. Archäologie der Schweiz 22(4):170–179

Hauschild M, Schönfelder M, Scheeres M, Knipper C, Alt KW, Pare C (2013) Nebringen, Münsingen und Monte Bibele - Zum archäologischen und bioarchäometrischen Nachweis von Mobilität im 4./3. Jahrhundert v. Chr. Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt 43(3):345–364

Heigold-Stadelmann A, Ulrich-Bochsler S (2009) Anthropologische Auswertung der Gräber. In: Eggenberger P, Bacher R, Frey J, Frey-Kupper S, Heigold-Stadelmann A, Ulrich-Bochsler S (Eds) Seeberg, Pfarrkirche. Die Ergebnisse der Bauforschungen von 1999/2000. Bern, pp. 217–252

Hengen OP (1971) Cribra Orbitalia - Pathogenesis and Probable Etiology. Homo 22(2):57–76

Hillson S (1996) Dental Anthropology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hochuli S, Niffeler U, Rychner V (eds) (1998) Bronzezeit - Age du Bronze - Età del Bronzo. SPM III. Verlag Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Ur- und Frühgeschichte, Basel

Hodson FR (1968) The la Tène Cemetery at Münsingen-Rain. Acta Bernensia V. Verlag Stämpfli & CIE AG Bern, Bern

Hodson FR (1998) Reflections on Münsingen-Rain with a note on “Münsingen Fibulae.” In: Müller F (ed) Münsingen-Rain, ein Markstein der keltischen Archäologie. Funde, Befunde und Methoden im Vergleich. Akten des Internationalen Kolloquiums «Das keltische Gräberfeld von Münsingen-Rain 1906–1996». Verlag Bernisches Historisches Museum, Bern, pp 29–36

Hofeneder A (2005) Die Religion der Kelten in den antiken literarischen Zeugnissen. Sammlung, Übersetzung und Kommentierung. Bd. I: Von den Anfängen bis Caesar. Verlag der österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien

Hofmann P, Simon C (1991) Une sépulture de La Tène ancienne au Landeron. Etude archéologique et anthropologique. Jahrbuch der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Ur- und Frühgeschichte 74:203–209

Hofstetter T (2018) Etude paléoanthropologique et analyse des rituels funéraires de deux sites laténiens valaisans - Randogne-Bluche et Sion-Parking des Remparts. Archaeopress, Paris

Horisberger B (2019) Keltische und römische Eliten im zürcherischen Furttal. Gräber, Strassen und Siedlungen von der Frügbronzezeit bis in die Neuzeit: Ergebnisse der Rettungsgrabungen 2009–2018 in Regensdorf-Geissberg/Gubrist. Fotorotar, Zürich/Egg

Horisberger B, Müller K, Cueni A, Rast-Eicher A (2004) Bestattungen des 6./7. Jh. aus dem früh- spätmittelalterlichen Gräberfeld Baar ZG-Zugerstrasse. Jahrbuch der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Ur- und Frühgeschichte 87:163–214

Hug E (1956) Die Anthropologische Sammlung im Naturhistorischen Museum Bern. Naturhistorisches Museum Bern, Bern

Hüglin S, Spichtig N (2010) War crime or élite burial: interpretations of human skeletons within the late La Tène settlement Basel-Gasfabrik, Basel Switzerland European. J Archaeol 13(3):313–335

Jory S (2012) Chevenez-Au Breuille (JU); Eine Latènezeitliche Siedlung in der Ajoie mit einer singulären Keramikdeponierung-Auswertung eines Areals der Grabungskampagne 2012. Universität Basel, Basel

Jud P (1998) Untersuchungen zur Struktur des Gräberfeldes von Münsingen-Rain. In: Müller F (ed) Münsingen-Rain, ein Markstein der keltischen Archäologie. Funde, Befunde und Methoden im Vergleich. Akten des Internationalen Kolloquiums «Das keltische Gräberfeld von Münsingen-Rain 1906–1996». Verlag Bernisches Historisches Museum, Bern

Jud P (2007) Les ossements humains dans les sanctuaires laténiens de la région des Trois-Lacs. In: Barral P, Daubigney A, Dunning C, Kaenel G, Roulière-Lambert M-J (eds) L’âge du Fer dans l’arc jurassien et ses marges Dépots, lieux sacrés et territorialité à l’âge du Fer, vol 2. Presses universitaires de Franche-Comté, Besançon, pp 391–398

Jud P (2009) Die latènezeitlichen Gräber von Gumefens. Cahiers d’archéologie Fribourgeoise 11:56–109

Jud P, Spichtig N (1999) Vorbericht über die Grabungen 1998 im Bereich der spätlatènezeitlichen Siedlung Basel-Gasfabrik. Jahresbericht Archäologische Bodenforschung des Kantons Basel-Stadt 1998:83–91

Jud P, Ulrich-Bochsler S (2014) Bern, Reichenbachstrasse Die Gräber aus dem Oppidum auf der Engehalbinsel Bern. Archäologischer Dienst des Kantons Bern, Bern

Kaenel G (1990) Recherches sur la période La Tène en Suisse occidentale - Analyse des sépultures. Bibliothèque historique vaudoise, Lausanne

Kaenel G (1995) L’âge du Fer. Archäologie der Schweiz 18(2):68–77

Kaenel G (1999) Die Archäologie der Eisenzeit in der Schweiz. In: Müller F, Kaenel G, Lüscher G (eds) Die Schweiz vom Paläolithikum bis zum frühen Mittelalter. SPM IV Eisenzeit. Verlag Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Ur- und Frühgeschichte, Basel, pp 15–23

Kaenel G (2007) La Tène: un site archéologique d’envergure européenne. In: Betschart M, Delley G (eds) La Tène. La Recherche – Les Questions – Les Réponses. Catalogue de l’exposition au Musée Schwab Bienne et au Musée national suisse. Verlag Museum Schwab, Biel, pp 12–16

Kaenel G, Favre S (1983) La nécropole celtique de Gempenach/Champagny (district du Lac/FB): les fouilles de 1979. Jahrbuch der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Ur- und Frühgeschichte 66:189–213

Katzenberg MA (2007) Stable isotope analysis: a tool for studying past diet, demography, and life history. In: Katzenberg MA, Saunders SR (eds) Biological anthropology of the human skeleton, 2nd edn. Wiley-Liss, New York, pp 411–441

Kaufmann B, Scheidegger S, Xirotiris N (1989) Güttingen TG, "Grauer Stein": Bearbeitung der menschlichen Skelettreste aus den Grabungen 1927, 1966 und 1973. Aesch

Kaufmann B, Schoch M (1983) Ried/Mühlehölzli. Ein Gräberfeld mit frühmittelalterlichen und hallstattzeitlichen Bestattungen. Anthropologie (vol 1b). Universitätsverlag Freiburg, Freiburg

Kaufmann B, Schoch W (1990) Anthropologische Bearbeitung der Skelette des römischen Reihengräberfeldes von Tafers/Windhalta. Archéologie Fribourgeoise Chronique Archéologique 1987–1988:170–188

Kearney M (1986) From the invisible hand to visible feet: anthropological studies of migration and development. Annu Rev Anthropol 15:331–361

Keller-Tarnuzzer K (1933) Die eisenzeitliche Siedlung von Castaneda: Grabung 1932. Anzeiger für schweizerische Altertumskunde 35(3):161–177

Knipper C, Pichler SL, Rissanen H, Stopp B, Kühn M, Spichtig N, … Alt KW (2017) What is on the menu in a Celtic town? Iron Age diet reconstructed at Basel-Gasfabrik, Switzerland. J Archaeol Anthropol Sci 9:1307–1326. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-016-0362-8

Knipper C, Pichler SL, Brönnimann D, Rissanen H, Rosner M, Spichtig N, … Lassau G (2018) A knot in a network: residential mobility at the Late Iron Age proto-urban centre of Basel-Gasfabrik (Switzerland) revealed by isotope analyses. J Archaeol Sci 17:735–753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2017.12.001

Knipper C, Warnberg O, Alt KW (2014) Analyses génétiques et isotopiques appliquées à la population du Mormont. Archéothéma, Hors-Série 7:51

Kramis S, Trancik V (2014) “Extra locos sepulturae” – Literaturreview zu römerzeitlichen Perinatenfunden auf dem Gebiet der heutigen Schweiz. Bulletin der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie 20(2):5–26

Kruta V (2009) La grande storia dei Celti. Newton & Compton, Roma

Laffranchi Z, Cavalieri Manasse G, Salzani L, Milella M (2019) Patterns of funerary variability, diet, and developmental stress in a Celtic population from NE Italy (3rd-1st c BC). PLoS ONE 14(4):e0214372

Laffranchi Z, Delgado Huertas AD, Jiménez Brobeil SA, Granados Torres AG, Riquelme Cantal JA (2016) Stable C & N isotopes in 2100 Year-BP human bone collagen indicate rare dietary dominance of C4 plants in NE-Italy. Sci Rep 6:38817. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38817

Laffranchi Z, Milella M, Lombardo P, Langer R, Lösch S (2021) Co-occurrence of malignant neoplasm and Hyperostosis Frontalis Interna in an Iron Age individual from Münsingen-Rain (Switzerland): A multi-diagnostic study. Int J Paleopathol 32:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpp.2020.10.008

Lange G (1995) Die menschlichen Skelettreste aus der Latenesiedlung von Bad Nauheim. Fundberichte aus Hessen 29/30:277–319

Langenegger E (1995) Anthropologischer Bericht. In: Windler R (ed) Das Gräberfeld von Elgg und die Besiedlung der Nordostschweiz im 5.–7 Jh. Fotorotar AG, Zürich/Elgg, pp 178–185

Langenegger E (1996) »Hominem priusquam genito dente cremari mos genitum non est.« Zu den Neonatengräbern im römischen Gutshof von Neftenbach ZH. Archäologie Schweiz 19(4):156–158

Le Huray JD, Schutkowski H (2005) Diet and social status during the La Tène period in Bohemia: carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analysis of bone collagen from Kutná Hora-Karlov and Radovesice. J Anthropol Archaeol 24(2):135–147

Lee ES (1966) A theory of migration. Demography 3:47–57

Lehner H-J (1987) Die Ausgrabungen in Sitten “Sous-le-Scex”. Zwischenbericht über die Arbeiten von 1984 bis 1987. Archäologie der Schweiz 10(4):145–156

Lehner HJ (1986) Ein keltisches Mädchengrab unter der Pfarrkirche zu Stans NW. Archäologie der Schweiz 9:6–8

Lewis ME (2007) The bioarchaeology of children: perspectives from biological and forensic anthropology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Lightfoot E, O’Connell TC (2016) On the use of biomineral oxygen isotope data to identify human migrants in the archaeological record: intra-sample variation, statistical methods and geographical considerations. PLoS One 11(4):e0153850. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153850

Lohrke B (2002) Kinder in der Merowingerzeit. In: Alt KW, Kemkes-Grottenthaler A (eds) Kinderwelten. Anthropologie, Geschichte, Kulturvergleich. Böhlau, Köln, pp 140–153

Lösch S, Gubler R, Rüttimann D, Moghaddam N, Schwarz H, Cueni A (2013) Die römischen Bestattungen der Grabung Wydenpark in Studen Eine anthropologische Untersuchung. Archäologie Bern/Archéologie bernoise 2013:120–134

Lüscher G, Müller F (1999) Gräber und Kult. In: Müller F, Kaenel G, Lüscher G (eds) Eisenzeit. Verlag Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Ur- und Frühgeschichte, Basel, pp 249–282

Maroelli D, Gallay A (2014) Orny – Sous-Mormont. Des sépultures du début du Second âge du Fer au pied de la colline du Mormont. Archéologie Vaudoise Chroniques 2014:44–57

Martelli S (2002) Die anthropologischen Untersuchungen des Knochenmaterials von Mesocco Coop. In: Schmid-Sikimic B (ed) Mesocco Coop (GR). Eisenzeitlicher Bestattungsplatz im Brennpunkt zwischen Süd und Nord. Habelt, Bonn, pp 129–136

Marti R (2008) Pratteln BL. Meierhof. Jahrbuch Archäologie Schweiz 91:227

Marti R, Baeriswyl A, Boschetti-Maradi A, Descoeudres G, Frascoli L, Niffeler U, … Windler R (Eds) (2014) Archäologie der Zeit von 800 bis 1350, Vol. VII. Verlag Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Ur- und Frühgeschichte, Basel

Martin-Kilcher S (1976) Das römische Gräberfeld von Courroux im Berner Jura. Habegger Verlag, Derendingen

Massey DS, Arango J, Hugo G, Kouaouci A, Pellegrino A, Taylor JE (1993) Theories of international migration - a review and appraisal. Popul Dev Rev 19:431–466

Menoud S, Ramseyer D (1995) Kerzers: Vennerstrasse. Freiburger Archäologie Archäologischer Fundbericht 1995:41–46

Mensforth RP, Lovejoy CO, Lallo JW, Armelagos GJ (1978) The role of constitutional factors, diet, and infectious disease in the etiology of porotic hyperostosis and periosteal reactions in prehistoric infants and children. Med Anthropol 2(1):1–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.1978.9986939

Meyer C, Alt KW (2012) Anthropologische Untersuchung der menschlichen Skelettfunde aus dem endneolithischen Kollektivgrab von Spreitenbach: osteologischer Individualbefund und Populationscharakteristik. In: Doppler T (ed) Spreitenbach-Moosweg (Aargau, Schweiz): Ein Kollektivgrab um 2500 v. Chr. Urs Zuber AG, Basel, pp 104–157

Milella M, Gerling C, Doppler T, Kuhn T, Cooper M, Mariotti V, … Zollikofer CP (2019) Different in death: different in life? Diet and mobility correlates of irregular burials in a Roman necropolis from Bologna (Northern Italy, 1st-4th century CE). J Archaeol Sci: Rep 27:101926

Milella M, Mariotti V, Belcastro MG, Knüsel CJ (2015) Patterns of irregular burials in Western Europe (1st -5th century A.D.). PLoS One 10(6):e0130616. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130616

Mittler DM, Van Gerven DP (1994) Developmental, diachronic, and demographic analysis of cribra orbitalia in the medieval Christian populations of Kulubnarti. Am J Phys Anthropol 93(3):287–297. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330930302

Moghaddam N (2016) Diet, status, and mobility in Late Iron Age Switzerland: a bioarchaeological study of human remains based on stable isotope analyses. (PhD), University of Bern, Bern

Moghaddam N, Langer R, Ross S, Lösch S (2013a) A case of a malign tumour from La Tène Burial Site of Münsingen Rain, Switzerland. Am J Phys Anthropol 150(S56):200–201

Moghaddam N, Langer R, Ross S, Nielsen E, Lösch S (2013b) Multiple osteosclerotic lesions in an Iron Age skull from Switzerland (320–250 BC) - an unusual case. Swiss Medical Weekly 143:w13819. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2013.13819

Moghaddam N, Lösch S (2015) Anthropologische Untersuchungen der fünf latènezeitlichen Gräber aus Ipsach. Archäologie Bern/archéologie Bernoise 2015:113–115

Moghaddam N, Mailler-Burch S, Kara L, Kanz F, Jackowski C, Lösch S (2015) Survival after trepanation—early cranial surgery from Late Iron Age Switzerland. Int J Paleopathol 11:56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpp.2015.08.002

Moghaddam N, Müller F, Hafner A, Lösch S (2016) Social stratigraphy in Late Iron Age Switzerland: stable carbon, nitrogen and sulphur isotope analysis of human remains from Münsingen. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 8(1):149–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-014-0221-4

Moghaddam N, Müller F, Lösch S (2018) A bioarchaeological approach to the Iron Age in Switzerland – stable isotope analyses (δ13C, δ15N, δ34S) of human remains. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 10(5):1067–1085. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-016-0441-x

Moinat P (1993) Deux inhumations en position assise à Avenches. Bulletin De L’association pro Aventico 35(1993):5–13

Moinat P (2009) Corps en tous sens. In: Le Mormont. Un sanctuaire des Helvètes en terre vaudoise vers 100 avant J.-C. Archeodunum, Lausanne, pp 5–8

Moinat P, Simon C (1986) Nécropole de Chamblandes-Pully, nouvelles observations. Jahrbuch der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Ur- Und Frühgeschichte 69:39–53

Montgomery J (2010) Passports from the past: investigating human dispersals using strontium isotope analysis of tooth enamel. Ann Hum Biol 37(3):325–346. https://doi.org/10.3109/03014461003649297

Moret J-C, Rast-Eicher A, Taillard P (2000) Sion: les secrets d’une tombe “sédune.” Archäologie Schweiz 23(1):10–17

Müller F (1996) Latènezeitliche Grabkeramik aus dem Berner Aaretal. Jahrbuch der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Ur-und Frühgeschichte 79:43–66

Müller F (1998) Münsingen-Rain, ein Markstein der keltischen Archäologie. Funde, Befunde und Methoden im Vergleich. Akten des Internationalen Kolloquiums «Das keltische Gräberfeld von Münsingen-Rain 1906–1996». Verlag Bernisches Historisches Museum, Bern

Müller F (2002) Götter, Gaben, Rituale. Religion in der Frühgeschichte Europas. Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz

Müller F (2009) Le mobilier mis au jour à l’emplacement des ponts de La Tène: offrandes, trophées, objects funéraires? In: Honegger M, Ramseyer D, Kaenel G, Arnold B, Kaeser M-A (eds) Le site de La Tène: bilan des connaissances - état de la question. Hauterive, pp 87–92

Müller F, Kaenel G, Lüscher G (eds) (1999) Eisenzeit - Age du Fer - Età del Fero. SPM IV. Verlag Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Ur- und Frühgeschichte, Basel

Müller F, Lüscher G (2004) Die Kelten in der Schweiz. Konrad Theiss Verlag GmbH, Stuttgart

Nagy P (2000) Castaneda, eine eisenzeitliche Siedlung und Nekropole im südlichen Misox. In: Ticino GA (ed) I Leponti Tra mito e realtà. Armando Dadò, Locarno, pp 299–308

Nagy P (2008) Das eisenzeitliche Gräberfeld von Castaneda, Kanton Graubünden. (PhD), University of Zurich, Zurich

Nielsen E (2014) Eine noble Keltin aus Sursee-Hofstetterfeld. Archäologie Schweiz 37(1):4–15

Papageorgopoulou C (2008). The medieval population of Tomils/Sogn Murezi – an archaeoanthropological approach. (PhD Thesis), University of Basel, Basel

Papathanasiou A, Meinzer NJ, Williams KD, Larsen CS (2018) The history of anemia and related nutritional deficiencies in Europe: evidence from cribra orbitalia and porotic hyperostosis. In: Steckel R, Larsen C, Robers C, Baten J (eds) The backbone of Europe: health, diet, work and violence over two millennia. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 198–230

Parker Pearson M (1982) Mortuary practices, society and ideology: an ethnoarchaeological study. In: Hodder I (ed) Symbolic and structural archaeology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 99–114

Parker Pearson M (1993) The powerful dead: archaeological relationships between the living and the dead. Camb Archaeol J 3:203–229. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774300000846

Pichler S, Rissanen H, Spichtig N (2015) Ein Platz unter den Lebenden, ein Platz unter den Toten - Kinderbestattungen des latènezeitlichen Fundplatzes Basel-Gasfabrik. In: Kory RW, Masanz R (eds) Lebenswelten von Kindern und Frauen in der Vormoderne - Archäologische und anthropologische Forschungen in memoriam Brigitte Lohrke vol. 4. Curach Bhán, Berlin, pp 257–273

Pichler S, Rissanen H, Spichtig N, Alt KW, Röder B, Schibler J, Lassau G (2013) Die Regelmässigkeit des Irregulären: Menschliche Skelettreste vom spätlatènezeitlichen Fundplatz Basel-Gasfabrik. In: Müller-Scheeßel N (Ed) “Irreguläre” Bestattungen in der Urgeschichte: Norm, Ritual, Strafe ...? Akten der Internationalen Tagung in Frankfurt a. M. vom 3. bis 5. Februar 2012. Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn, pp 471–484

Pichler SL, Pümpin C, Brönnimann D, Rentzel P (2014) Life in the proto-urban style: the identification of parasite eggs in micromorphological thin sections from the Basel-Gasfabrik Late Iron Age settlement, Switzerland. J Archaeol Sci 43:55–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2013.12.002

Primas M (1970) Die südschweizerischen Grabfunde der älteren Eisenzeit und ihre Chronologie. Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel

Ramseier F, Hotz G, Meyer L (2005) Prehistoric trepanations of Switzerland-from the Neolithic to the Middle Ages. Bulletin der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie 11(1–2):1–58

Ramseyer D (1997) Une nécropole celtique à Chiètres (Kerzers) FR. Archäologie Schweiz 20(3):126–132

Ramseyer D (2009) Le pont celtique de Cornaux/Les Sauges: accident ou lieu de sacrifices? In: Honegger M, Ramseyer D, Kaenel G, Arnold B, Kaeser M-A (Eds) Le site de La Tène: bilan des connaissances – état de la question. Actes de la Table Ronde Internationale de Neuchâtel (1–3 nov. 2007). Service et musée cantonal d'archéologie de Neuchâtel, Hauterive, pp 103–111

Ramstein M (2010) Ipsach, Räberein - Latènezeitliche Gräber im römischen Gutshofareal. ArchBE Jahrbuch des Archäologischen Dienstes des Kantons Bern 2009:96–97

Ramstein M, Ulrich-Bochsler S (2006) Worb-Worbberg. Römisches Körpergrab. Archäologie im Kanton Bern 6:659–666

Reinhard KJ (1992) Patterns of diet, parasitism, and anemia in prehistoric West North America. In: Stuart-Macadam P, Kent S (eds) Diet, demography and disease: changing patterns on anemia. New York, pp 220–258

Reitmaier T (2020) Cama und Rhäzüns - neue Grabfunde aus Graubünden. Archäologie Schweiz 43(1):46

Rey T (1999) Das latènezeitliche Gräberfeld von Stettlen-Deisswil BE. Jahrbuch der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Ur- und Frühgeschichte 82:117–148

Rissanen H, Pichler S, Spichtig N, Alt KW, Brönnimann D, Knipper C, … Lassau G (2013) Wenn Kinder sterben…“ – Säuglinge und Kleinkinder vom latènezeitlichen Fundplatz Basel-Gasfabrik (Kanton Basel-Stadt, Schweiz). In: Wefers S, Fries JE, Fries-Knoblach J, Later C, Rambuscheck U, Trebsche P, Wiethold J (Eds) Beiträge zur gemeinsamen Sitzung der AG Eisenzeit und der AG Geschlechterforschung während des 7. Deutschen Archäologenkongresses in Bremen 2011. Beier & Beran, Langenweissbach, pp 127–142

Ruffieux M, Vigneau H, Mayuvilly M, Duvauchelle A, Guélat M, Kramar C, … Uldin T (2006) Deux Nécropoles de La Tène finale dans la Broye: Chables/Les Biolleyres 3 et Frasses/Les Champs Montants. Cahiers d'Archéologie Fribourgeoise 8:4–111

Schaer N, Stopp B (2005) Bestattet oder entsorgt? Das menschliche Skelett aus der Grube 145/230 von Basel Gasfabrik. Materialhefte zur Archäologie in Basel 19:203

Scheeres M, Knipper C, Hauschild M, Schonfelder M, Siebel W, Pare C, Alt KW (2014) “Celtic migrations”: fact or fiction? Strontium and oxygen isotope analysis of the Czech cemeteries of Radovesice and Kutna Hora in Bohemia. Am J Phys Anthropol 155:496–512

Scheffrahn W (1967) Paläodemographische Beobachtungen an den Neolithikern von Lenzburg Kt. Aargau. Germania 45:34–42

Scheffrahn W (1998) Die anthropologischen Befunde der neolithischen Population von Lenzburg. In: Schweizerisches Landesmuseum Zürich (ed) Archäologische Forschungen. Schweizerisches Landesmuseum Zürich, Zürich

Schoch W, Kaufmann B, Scheidegger S (1989) Die Skelettreste von Windisch-Rebengässli, Grabung 1985. Gesellschaft pro Vindonissa Jahresbericht 1988(89):12–53

Schoch W, Ulrich-Bochsler S (1987) Die Anthropologische Sammlung des Naturhistorischen Museums Bern - Katalog der Neueingänge 1956–1985. Jahrbuch Des Naturhistorischen Museums Bern 9:267–350

Schoeninger MJ (2011) Diet reconstruction and ecology using stable isotope ratios. In: Larsen C (ed) A companion to biological anthropology. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, pp 445–464

Schwab H (1989) Archéologie de la deuxième correction des eaux du Jura 1 Les Celtes sur la Broye et la Thielle. Editions Universitaires, Fribourg

Seifert M (2000) Das spätbronzezeitliche Grab von Domat/Ems - Eine Frau aus dem Süden? Archäologie der Schweiz 23(2):76–83