Abstract

Background

Birth weight is a strong determinant of infant short- and long-term health outcomes. Family socioeconomic position (SEP) is usually positively associated with birth weight. Whether this association extends to abnormal birth weight or there exists potential mediator is unclear.

Methods

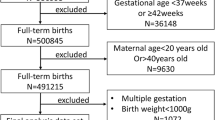

We analyzed data from 14,984 mother-infant dyads from the Born in Guangzhou Cohort Study. We used multivariable logistic regression to assess the associations of a composite family SEP score quartile with macrosomia and low birth weight (LBW), and examined the potential mediation effect of maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) using causal mediation analysis.

Results

The prevalence of macrosomia and LBW was 2.62% (n = 392) and 4.26% (n = 638). Higher family SEP was associated with a higher risk of macrosomia (OR 1.30, 95% CI 0.93–1.82; OR 1.53, 95% CI 1.11–2.11; and OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.15–2.20 for the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th SEP quartile respectively) and a lower risk of LBW (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.55–0.86; OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.61–0.94; and OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.48–0.77 for the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th SEP quartile respectively), compared to the 1st SEP quartile. We found that pre-pregnancy BMI did not mediate the associations of SEP with macrosomia and LBW.

Conclusions

Socioeconomic disparities in fetal macrosomia and LBW exist in Southern China. Whether the results can be applied to other populations should be further investigated.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Li X, Lu J, Hu S, Cheng KK, De Maeseneer J, Meng Q, et al. The primary health-care system in China. Lancet. 2017;390:2584–94.

Wang H, Yip W, Zhang L, Hsiao WC. The impact of rural mutual health care on health status: evaluation of a social experiment in rural China. Health Econ. 2009;18(Suppl 2):S65–82.

Jie P, XueZheng Q. Does health insurance promote health? Literature review. World Econ Paper. 2014;(6):60–70 (Chinese).

Statistics Bureau of Guangzhou Municipality. Principal aggregate indicators on national economic and social development and growth rates in annual statistics of 2015. 2015. https://210.72.4.52/gzStat1/chaxun/ndsj.jsp. Accessed 8 April 2018.

Meertens L, Smits L, van Kuijk S, Aardenburg R, van Dooren I, Langenveld J, et al. External validation and clinical usefulness of first-trimester prediction models for small- and large-for-gestational-age infants: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2019;126:472–84.

Koyanagi A, Zhang J, Dagvadorj A, Hirayama F, Shibuya K, Souza JP, et al. Macrosomia in 23 developing countries: an analysis of a multicountry, facility-based, cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2013;381:476–83.

Li Y, Ley SH, Tobias DK, Chiuve SE, VanderWeele TJ, Rich-Edwards JW, et al. Birth weight and later life adherence to unhealthy lifestyles in predicting type 2 diabetes: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2015;351:h3672.

Ju H, Chadha Y, Donovan T, O'Rourke P. Fetal macrosomia and pregnancy outcomes. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;49:504–9.

Wang D, Hong Y, Zhu L, Wang X, Lv Q, Zhou Q, et al. Risk factors and outcomes of macrosomia in China: a multicentric survey based on birth data. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30:623–7.

Chen Y, Li G, Ruan Y, Zou L, Wang X, Zhang W. An epidemiological survey on low birth weight infants in China and analysis of outcomes of full-term low birth weight infants. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:242.

McCormick MC. The contribution of low birth weight to infant mortality and childhood morbidity. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:82–90.

Rijpert M, Evers IM, de Vroede MA, de Valk HW, Heijnen CJ, Visser GH. Risk factors for childhood overweight in offspring of type 1 diabetic women with adequate glycemic control during pregnancy: Nationwide follow-up study in the Netherlands. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2099–104.

Gigante DP, Horta BL, Matijasevich A, Mola CL, Barros AJ, Santos IS, et al. Gestational age and newborn size according to parental social mobility: an intergenerational cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69:944–9.

Madden D. The relationship between low birth weight and socioeconomic status in Ireland. J Biosoc Sci. 2014;46:248–65.

Nandi A, Glymour MM, Subramanian SV. Association among socioeconomic status, health behaviors, and all-cause mortality in the United States. Epidemiology. 2014;25.

Johnson RC, Schoeni RF. The influence of early-life events on human capital, health status, and labor market outcomes over the life course. B E J Econom. Anal Policy 2011;11. pii: 2521.

Blumenshine P, Egerter S, Barclay CJ, Cubbin C, Braveman PA. Socioeconomic disparities in adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39:263–72.

Barr AB. Family socioeconomic status, family health, and changes in students' math achievement across high school: a mediational model. Soc Sci Med. 2015;140:27–34.

Clayborne ZM, Giesbrecht GF, Bell RC, Tomfohr-Madsen LM. Relations between neighbourhood socioeconomic status and birth outcomes are mediated by maternal weight. Soc Sci Med. 2017;175:143–51.

Qiu X, Lu JH, He JR, Lam KH, Shen SY, Guo Y, et al. The Born in Guangzhou Cohort Study (BIGCS). Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32:337–46.

He JR, Yuan MY, Chen NN, Lu JH, Hu CY, Mai WB, et al. Maternal dietary patterns and gestational diabetes mellitus: a large prospective cohort study in China. Br J Nutr. 2015;113:1292–300.

Vyas S, Kumaranayake L. Constructing socio-economic status indices: how to use principal components analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2006;21:459–68.

Wei DM, Au Yeung SL, He JR, Xiao WQ, Lu JH, Tu S, et al. The role of social support in family socio-economic disparities in depressive symptoms during early pregnancy: evidence from a Chinese birth cohort. J Affect Disord. 2018;238:418–23.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) – Technical Paper, 2006. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/2039.0.55.001. Accessed 26 Mar 2008.

World Health Organization. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) classification of mental and behavioral disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Delhi: Oxford University Press; 1992.

Lawlor DA, Mortensen L, Andersen A-MN. Mechanisms underlying the associations of maternal age with adverse perinatal outcomes: a sibling study of 264695 Danish women and their firstborn offspring. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:1205–14.

Nybo Andersen AM, Wohlfahrt J, Christens P, Olsen J, Melbye M. Maternal age and fetal loss: population based register linkage study. BMJ. 2000;320:1708–12.

Yu ZB, Han SP, Zhu GZ, Zhu C, Wang XJ, Cao XG, et al. Birth weight and subsequent risk of obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2011;12:525–42.

Zhang T, Cai L, Ma L, Jing J, Chen Y, Ma J. The prevalence of obesity and influence of early life and behavioral factors on obesity in Chinese children in Guangzhou. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:954.

Gonzalez-Quintero VH, Istwan NB, Rhea DJ, Rodriguez LI, Cotter A, Carter J, et al. The impact of glycemic control on neonatal outcome in singleton pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:467–70.

Mengesha HG, Wuneh AD, Weldearegawi B, Selvakumar DL. Low birth weight and macrosomia in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia: who are the mothers at risk? BMC Pediatr. 2017;17:144.

Chen C, Lu FC, Department of Disease Control Ministry of Health PRC. The guidelines for prevention and control of overweight and obesity in Chinese adults. Biomed Environ Sci. 2004;17 Suppl:1–36.

International Association of D, Pregnancy Study Groups Consensus P, Metzger BE, Gabbe SG, Persson B, Buchanan TA et al. International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:676–82.

Valeri L, Vanderweele TJ. Mediation analysis allowing for exposure-mediator interactions and causal interpretation: theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychol Methods. 2013;18:137–50.

Fujiwara T, Ito J, Kawachi I. Income inequality, parental socioeconomic status, and birth outcomes in Japan. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:1042–52.

Pei L, Kang Y, Zhao Y, Cheng Y, Yan H. Changes in socioeconomic inequality of low birth weight and macrosomia in Shaanxi Province of Northwest China, 2010–2013: A Cross-sectional Study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e2471.

Leung JY, Leung GM, Schooling CM. Socioeconomic disparities in preterm birth and birth weight in a non-Western developed setting: evidence from Hong Kong's 'Children of 1997' birth cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70:1074-81.

Zanetti D, Tikkanen E, Gustafsson S, Priest JR, Burgess S, Ingelsson E. Birthweight, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease: addressing the barker hypothesis with Mendelian randomization. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2018;11:e002054.

Au Yeung SL, Lin SL, Li AM, Schooling CM. Birth weight and risk of ischemic heart disease: a Mendelian randomization study. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38420.

Wang T, Huang T, Li Y, Zheng Y, Manson JE, Hu FB, et al. Low birthweight and risk of type 2 diabetes: a Mendelian randomisation study. Diabetologia. 2016;59:1920–7.

Ozaltin E, Hill K, Subramanian SV. Association of maternal stature with offspring mortality, underweight, and stunting in low- to middle-income countries. JAMA. 2010;303:1507–16.

Metcalfe A, Lail P, Ghali WA, Sauve RS. The association between neighbourhoods and adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of multi-level studies. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2011;25:236–45.

Rao J, Fan D, Wu S, Lin D, Zhang H, Ye S, et al. Trend and risk factors of low birth weight and macrosomia in south China, 2005–2017: a retrospective observational study. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3393.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the mothers and their families who have participated in BIGCS and all obstetric care providers who assisted in the implementation of the study. We also wish to thank Allison Gaines from University of Oxford for polishing the language of the paper.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers 81673181, 81703244, and 81803251).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XQ and HX conceived and designed the ongoing cohort study. ST, SS, DW, and ML collected the data. ST, AW, JL, and JH designed the statistical analysis in this paper. ST drafted and revised the manuscript. AW, MT, JH, and SLAY provided the technical and analysis advice and revised the manuscript. XQ supervised and provide specialist support for the manuscript. ST and AW contributed equally to this paper. All authors revised the important intellectual content critically and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The Born in Guangzhou Cohort Study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center.

Conflict of interest

No financial or nonfinancial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tu, S., Wang, AL., Tan, MZ. et al. Family socioeconomic position and abnormal birth weight: evidence from a Chinese birth cohort. World J Pediatr 15, 483–491 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-019-00279-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-019-00279-7