Abstract

Background

Despite advances in pump technology, thromboembolic events/acute pump thrombosis remain potentially life-threatening complications in patients with continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices (CF-LVAD). We sought to determine early signs of thromboembolic event/pump thrombosis in patients with CF-LVAD, which could lead to earlier intervention.

Methods

We analysed all HeartMate II recipients (n = 40) in our centre between December 2006 and July 2013. Thromboembolic event/pump thrombosis was defined as a transient ischaemic attack (TIA), ischaemic cerebrovascular accident (CVA), or pump thrombosis.

Results

During median LVAD support of 336 days [IQR: 182–808], 8 (20 %) patients developed a thromboembolic event/pump thrombosis (six TIA/CVA, two pump thromboses). At the time of the thromboembolic event/pump thrombosis, significantly higher pump power was seen compared with the no-thrombosis group (8.2 ± 3.0 vs. 6.4 ± 1.4 W, p = 0.02), as well as a trend towards a lower pulse index (4.1 ± 1.5 vs. 5.0 ± 1.0, p = 0.05) and a trend towards higher pump flow (5.7 ± 1.0 vs. 4.9 ± 1.9 L m, p = 0.06).

The thrombosis group had a more than fourfold higher lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) median 1548 [IQR: 754–2379] vs. 363 [IQR: 325–443] U/L, p = 0.0001). Bacterial (n = 4) or viral (n = 1) infection was present in 5 out of 8 patients. LDH > 735 U/L predicted thromboembolic events/pump thrombosis with a positive predictive value of 88 %.

Conclusions

In patients with a CF-LVAD (HeartMate II), thromboembolic events and/or pump thrombosis are associated with symptoms and signs of acute haemolysis as manifested by a high LDH, elevated pump power and decreased pulse index, especially in the context of an infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) have increasingly become part of the arsenal in the treatment of end-stage heart failure [1–3]. Despite advances in pump technology, thromboembolic events and acute pump thrombosis remain potentially life-threatening complications [4–6]. The clinical presentation varies from acute malfunction of the pump with heart failure, arrhythmias and/or to systemic thromboembolic events. The exact prevalence and aetiology of pump thrombosis is uncertain [7]. Rates of thromboembolic events, including ischaemic stroke and acute pump thrombosis, vary between 1 and 14 % among different studies of continuous flow (CF) LVADs with either axial or centrifugal flow [6, 8–15].

Recently, Starling et al. reported an increasing rate of Thoratec HeartMate II pump thrombosis, which was preceded by increasing lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and was associated with substantial morbidity and mortality [16]. Other reports showed a strong association of haemolysis with increased pump power and with partial or complete LVAD thrombosis [17, 18]. The current guidelines of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) advise to follow up haemolysis as a sign of thrombosis [7]. Haemolysis in the presence of altered pump function should prompt admission for optimisation of anticoagulation and antiplatelet management and possible pump exchange [4]. However, there is no advice in the guidelines about detection of thrombosis. Clinically obvious haemolysis could be seen as dark urine, anaemia, jaundice, and/or as elevated LDH. Early detection of a thromboembolic event/pump thrombosis could help in the proper management of these LVAD patients.

As thromboembolic events and pump thrombosis are part of the same disease spectrum, we sought to analyse the determinants of thromboembolic events and/or pump thrombosis in the cohort of patients with a CF-LVAD implanted at our institution.

Methods

Forty consecutive patients implanted with axial type continuous-flow HeartMate II LVADs (Thoratec Corporation, Pleasanton, California) in our institution, a tertiary referral centre for end-stage heart failure and heart transplantation, between December 2006 and July 2013, were included in this study.

Data collection

All data from LVAD recipients were stored electronically in the hospital electronic patient records. According to Dutch law, informed consent was not required, since study-specific actions were not implemented. All data were readily available in the medical records of the patients and were obtained during routine treatment. Subsequently, data were processed anonymously. Data were retrospectively analysed for demographic, clinical and LVAD pump parameters. Clinical events such as signs of haemolysis, heart failure or infections were examined and confirmed independently by two cardiologists (SA, KC).

Clinical and laboratory investigation

Clinical data, ECG, laboratory and echocardiography were collected every 2–3 months or more frequently according to the clinical need. Likewise, LVAD interrogation was performed regularly at every outpatient clinic visit by an LVAD technician. The last 12-lead ECGs before LVAD implantation and at follow-up/events were analysed including rhythm, QRS width and QTc interval. Blood samples were collected serially to assess parameters of haemolysis, kidney and liver function as well as inflammation (Table 1). The treating cardiologist made the choice of and changes in medications including heart failure and antiarrhythmic drugs. Twenty-five of 40 patients (63 %) already had an implantable cardioverter defibrillator according to the current guidelines [19].

Antithrombotic therapy

According to the ISHLT guidelines, postoperative anticoagulation started after LVAD implantation and completed postoperative haemostasis [7]. On postoperative day 1–2, intravenous heparin was started if there was no evidence of bleeding. On day 2–5, after removal of the chest tubes, aspirin 80 mg daily and vitamin K antagonists were started with a target international normalised ratio (INR) of 2.0–2.5. In case of a suspected thromboembolic event/pump thrombosis, intravenous heparin was started along with clopidogrel 75 mg/day. The target INR was increased to 2.5–3.5 or 3.0–4.0 in case of asymptomatic (laboratory only) signs of haemolysis versus thromboembolic event/pump thrombosis, respectively. In case of acute pump thrombosis, thrombolytic therapy (alteplase: bolus 15 mg in 1–2 min, followed by 0.75 mg/kg (max. 50 mg) continuous infusion in 90 min, and 0.5 mg/kg (max. 35 mg) continuous infusion in the second 90 min) was given.

Outcome definitions

Pump thrombosis was defined as signs and symptoms of otherwise unexplained heart failure with signs of LVAD dysfunction and haemolysis, thromboembolic events as cerebrovascular accident (CVA) or transient ischaemic attack (TIA), as confirmed by a neurologist. Haemolysis was diagnosed according to the ISHLT guidelines and the Interagency Registry of Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) on analysis of pump thrombosis [7, 20]. Laboratory and clinical diagnosis of LVAD haemolysis and thrombosis were considered according to these ISHLT guidelines and the INTERMACS registry. In the ISHLT guidelines, screening for haemolysis is indicated in the setting of an unexpected drop in the haemoglobin or haematocrit level along with other clinical signs of haemolysis, such as haematuria. Screening for haemolysis with serum LDH, plasma free haemoglobin in addition to the haemoglobin or haematocrit level is recommended [7]. The INTERMACS recently specified a new definition, accepted by the US Food and Drug Administration and industry, indicating a lower threshold of biochemical markers of haemolysis. They used a cut-off value of serum free haemoglobin > 40 mg/dl in association with clinical signs of haemolysis beyond 72 h post-implantation to define haemolysis [7].

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range 25th, 75th percentile). Continuous variables were compared using paired or independent t-test, Mann–Whitney U-test or Wilcoxon’s test when appropriate. When comparing frequencies, the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used, where applicable. Cumulative Kaplan–Meier survival curves were constructed for each outcome variable. All tests were two-tailed and p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All p-values between 0.05 and 0.10 were considered to be a statistical trend. Multivariate analysis was not done due to the too low number of events and small population.

Results

In our single-centre LVAD cohort of bridge-to-transplant patients, we found clinical features and other factors associated with thromboembolic events and acute pump thrombosis in 8 of the 40 patients. One out of 5 patients on LVAD support with HeartMate II developed this catastrophic complication during a median follow-up of approximately 18 months. Thromboembolic events/pump thrombosis occurred at a minimum of 34 days and a maximal of 649 days after implantation. Demographic, clinical, laboratory, pump and echocardiography characteristics of the thrombosis and no-thrombosis groups at baseline and at follow-up are listed in Table 1 and 2, respectively. The patients were divided into two groups with and without a thromboembolic event and/or pump thrombosis. The baseline data are from the pre-implant period, the laboratory values from the day before the operation. In all patients, the LVAD was implanted as a bridge to transplant. However, in three patients LVAD support ended in destination therapy (severe CVAs in two and malignancy in one). In one patient, the LVAD could be explanted due to cardiac recovery. All patients were followed for a median of 336 (IQR 182–808) days. No patients were lost to follow-up.

At baseline, an intra-aortic balloon pump was used significantly more often in the thrombosis group, and this group had a higher blood urea nitrogen. Furthermore, the thrombosis group showed a trend towards INTERMACS class IV (p = 0.05) and less inotropic use (p = 0.05). At the last follow-up (July 2013), eight (20 %) patients had one or more thromboembolic events or pump thrombosis at median follow-up of 549 [269–856] days: TIA in 4 patients, ischaemic CVA in 3 patients and acute pump thrombosis in 2 patients. There was no difference in survival between the groups censored for heart transplantation or LVAD explantation (p = 0.13, Fig. 1). One patient with pump thrombosis was treated with acute pump replacement (Table 3 and Fig. 2a) and one patient underwent successful thrombolysis (Fig. 2b). Four patients in the no-thrombosis group had a non-ischaemic CVA, one due to an air embolism and three due to intracerebral bleeding. In these patients, a neurologist ruled out an ischaemic stroke by CT scan. At the time of the thromboembolic event/pump thrombosis, higher pump power was seen in thrombosis group compared with the no-thrombosis group (8.2 ± 3.0 vs. 6.4 ± 1.4 W, p = 0.02), as well as a trend towards a lower pulse index (4.1 ± 1.5 vs. 5.0 ± 1.0 p = 0.05) and a trend towards higher pump flow (5.7 ± 1.0 vs. 4.9 ± 1.9 L m p = 0.06) Macroscopic haemoglobinuria was seen in 4 of 8 patients of the thrombosis group and 3 of 32 patients of no-thrombosis group (50 vs. 9 %, p = 0.02). The patients in the thrombosis group with macroscopic haemoglobinuria had concomitant infections; at that time they had a therapeutic INR or activated partial thromboplastin time. They were all empirically treated with intravenous heparin and clopidogrel. None developed a thromboembolic event or pump thrombosis. The presence of a thrombus in the pump was confirmed at explantation by the thoracic surgeon and manufacturer in 4 of the 8 patients.

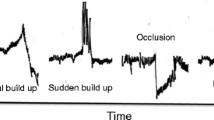

a Explanted pump inlet rotor in a 54-year-old male (patient no. 9 in Table 3) with acute pump thrombosis. Due to acute pump thrombosis, the patient had acute left- and right-sided heart failure with signs of severe haemolysis and acute renal failure. Macroscopic fresh white and red old thrombus is shown on the rotor, as confirmed by the manufacturer. b LDH course of the 57-year-old male (patient no. 7 in Table 3) presenting with acute pump thrombosis successfully treated with recombinant tissue-plasminogen activator (rt-PA). This patient had several episodes of an abrupt peak of LDH during therapeutic INRs associated with relapsing urinary tract infections (Citrobacter freundii). At the highest LDH peak he developed acute pump thrombosis, which was treated with thrombolytic therapy (alteplase). Dashed line = upper limit of normal value LDH. c Time course of serum LDH (U/L) in a 37-year-old woman (patient no. 5 in Table 3), 6 months on LVAD support, admitted with a ischaemic cerebrovascular event and response to various therapeutic interventions. CVA cerebrovascular accident, INR international normalised ratio, ASA acetylsalicylic acid, iv intravenous. Dashed line = upper limit of normal value LDH

Furthermore, the thrombosis group had more than fourfold higher lactate dehydrogenase levels (median LDH: 1548 [IQR: 754–2379] vs. 363 [IQR: 325–443] U/L, p < 0.0001). In the thrombosis group, infection was associated with a more than threefold increase of LDH with or without clinical signs of TIA/CVA or pump thrombosis. In 63 % (vs. 31 % in the no-thrombosis group, p = 0.13) of the patients presenting with thromboembolism/pump thrombosis, an infection (bacterial in 4 and viral in 1 of the 8 patients) was confirmed. At baseline and at follow-up, there was a significantly longer corrected-QT interval in the thrombosis group.

The sensitivity and specificity of LDH as a marker of haemolysis (cut-off value three times the upper limit of normal (LDH > 735 U/L) were 88 and 97 %, respectively, with the positive and negative predictive value being 88 vs. 97 %, respectively.

Discussion

In our single-centre LVAD cohort of bridge-to-transplant patients, we studied the clinical features and associated factors in patients with thromboembolic events and acute pump thrombosis. One out of 5 patients on LVAD support with a HeartMate II developed a thromboembolic event/pump thrombosis during a median follow-up of approximately 18 months. Infection was confirmed at the time of the event in two-thirds of these patients. Elevated pump power and macroscopic haemoglobinuria predicted thromboembolic events/pump thrombosis, but LDH more than three times the upper level of normal was the best biochemical parameter in predicting and guiding the management of LVAD-related thromboembolic events and/or acute pump thrombosis, with a sensitivity of 88 % and specificity of 97 %.

Thromboembolic events in continuous-flow LVADs

CF-LVADs have been increasingly used in the last decade as a bridge to transplantation [21]. Thromboembolic events/pump thrombosis remain one the most feared common complications in CF-LVAD patients, although bleeding results in the most morbidity and mortality [22–23]. The anticoagulation strategy of Whitson et al. [6] has been nuanced because it requires a delicate balance of adequate anticoagulation to minimise thrombotic complications but not so excessive that it will cause bleeding complications (e.g., gastrointestinal or neurological bleeding). What further complicates the clinical picture is the inherent haematological effects of CF-LVADs [24–25]. In our cohort there were 23/40 cases of early post-implantation bleeding, 21 of which resulted in early cardiac tamponade. In their analysis in 2008, John et al. [12] found a low thromboembolic risk (4.4 %) in HeartMate II patients even with less stringent requirements for anticoagulation, which was confirmed by Menon et al. in 2012 [13]. From 2013, there has been an increase in thromboembolic events/pump thrombosis in HeartMate II patients to 13.4 %, according to Whitson et al. [6]. In our report, 5 of the 40 patients (12.5 %) had a CVA or pump thrombosis, if TIAs were excluded due their mild clinical sequelae.

Acute pump thrombosis

Acute pump thrombosis is a life-threatening condition and its optimal management requires early intervention. Detection of the earliest signs of pump thrombosis could lead to successful thrombolysis of a soft developing thrombus [26]. Uriel et al. examined 177 LVAD patients of whom 19 (11 %) developed acute pump thrombosis, whereby all underwent pump exchange; the recurrence rate was 1 %. In one-third of the patients, inadequate anticoagulation was found due to withholding or cessation of anticoagulation [15]. Thrombolysis could also be used with varying effect, as in our cases in Fig. 2a, b and c [11, 27]. In our experience, the use of clopidogrel on top of aspirin and coumarins in optimising anticoagulation seems effective and safe, but the efficacy of antiplatelet therapy using clopidogrel in one study was not sufficient in more than 50 % of the patients [28].

Haemolysis

In a multicentre analysis it was recently demonstrated that haemolysis causes long-term negative effects in the long-term course of LVAD support [29]. In 7 % of their 115 patients with a HeartMate II, Hasin et al. found signs of haemolysis presenting with very high LDHs (more than six times normal) which after intensifying the anticoagulation therapy decreased to baseline within 2 weeks [11]. However, recurrent haemolysis was very common: 75 % over 1–7 months [11]. A recent analysis of the INTERMACS Registry of 4850 patients frequently found a mean time to event of 7.4 months and a cumulative incidence of 9 % at 2 years [29]. In another cohort of 20 consecutive cases of pump thrombosis, haematological markers, including LDH, plasma free haemoglobin and creatinine, were the only reliable sign of LVAD thrombosis, as opposed to echocardiographic or pump parameters.[30] Along with the emerging association of LDH with thromboembolism in patients with HeartMate II, there is also a growing association with acute infections [31], probably due to increased hypercoagulability [15, 31]. We can confirm this in our cohort, where there seems to be a correlation between infection and thrombosis in LVAD. LDH seems to be a very powerful parameter in predicting serious thromboembolic adverse events in HeartMate II patients.

Interestingly, the QTc was longer in the thrombosis group compared with the no-thrombosis group both at baseline and at latest follow-up. It is known that QTc is a very crucial prognostic parameter in end-stage heart failure and we see here an association with the development of thrombosis [32]. To our knowledge there are no reports on LVAD studies that have described this before. Further studies are needed to analyse these novel findings.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations, which should be taken into account in the final interpretation of the data. The design is a retrospective study, the number of cases is very limited, and there was no routine follow-up and analysis of eventual hypercoagulability and/or antiplatelet drugs resistance. Also, our findings were restricted to HeartMate II and may not be applicable to patients supported with other types of CF-LVADs.

Conclusion

In patients with CF-LVAD (HeartMate II), thromboembolic events and/or pump thrombosis are associated with symptoms and signs of acute haemolysis as manifested by high LDH, elevated pump power and decreased pulse index, especially in the context of an infection. These symptoms and signs could help in the early diagnosis and timely intensification of antithrombotic and/or antiplatelet therapy to prevent acute pump thrombosis and thromboembolic events or the need for pump replacement.

Funding

None.

References

Haeck ML, Beeres SL, Hoke U, et al. Left ventricular assist device for end-stage heart failure: results of the first LVAD destination program in the Netherlands. Neth Heart J. 2015;23(2):102–8.

Haeck ML, Hoogslag GE, Rodrigo SF, et al. Treatment options in end-stage heart failure: where to go from here? Neth Heart J. 2012;20(4):167–75.

Manintveld OC. Left ventricular assist device for end-stage heart failure: results of the first LVAD destination program in the Netherlands: towards LVAD destination therapy in the Netherlands? Neth Heart J. 2015;23(2):100–1.

Goldstein DJ, John R, Salerno C, et al. Algorithm for the diagnosis and management of suspected pump thrombus. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32(7):667–70.

Schaffer JM, Arnaoutakis GJ, Allen JG, et al. Bleeding complications and blood product utilization with left ventricular assist device implantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91(3):740–7. (discussion 7–9).

Whitson BA, Eckman P, Kamdar F, et al. Hemolysis, pump thrombus, and neurologic events in continuous-flow left ventricular assist device recipients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97(6):2097–103.

Feldman D, Pamboukian SV, Teuteberg JJ, et al. The 2013 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines for mechanical circulatory support: executive summary. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32(2):157–87.

Boyle AJ, Ascheim DD, Russo MJ, et al. Clinical outcomes for continuous-flow left ventricular assist device patients stratified by pre-operative INTERMACS classification. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30(4):402–7.

Boyle AJ, Jorde UP, Sun B, et al. Pre-operative risk factors of bleeding and stroke during left ventricular assist device support: an analysis of more than 900 HeartMate II outpatients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(9):880–8.

Boyle AJ, Russell SD, Teuteberg JJ, et al. Low thromboembolism and pump thrombosis with the HeartMate II left ventricular assist device: analysis of outpatient anti-coagulation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28(9):881–7.

Hasin T, Deo S, Maleszewski JJ, et al. The role of medical management for acute intravascular hemolysis in patients supported on axial flow LVAD. ASAIO J. 2014;60(1):9–14.

John R, Kamdar F, Liao K, et al. Low thromboembolic risk for patients with the Heartmate II left ventricular assist device. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;136(5):1318–23.

Menon AK, Gotzenich A, Sassmannshausen H, et al. Low stroke rate and few thrombo-embolic events after HeartMate II implantation under mild anticoagulation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;42(2):319–23. (discussion 23).

Moazami N, Milano CA, John R, et al. Pump replacement for left ventricular assist device failure can be done safely and is associated with low mortality. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95(2):500–5.

Uriel N, Han J, Morrison KA, et al. Device thrombosis in HeartMate II continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices: a multifactorial phenomenon. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33(1):51–9.

Starling RC, Moazami N, Silvestry SC, et al. Unexpected abrupt increase in left ventricular assist device thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(1):33–40.

Ravichandran AK, Parker J, Novak E, et al. Hemolysis in left ventricular assist device: a retrospective analysis of outcomes. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33(1):44–50.

Steffen RJ, Soltesz EG, Miracle K, et al. Incidence of increases in pump power use and associated clinical outcomes with an axial continuous-flow ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33(1):105–6.

McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14(8):803–69.

Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Kormos RL, et al. Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) analysis of pump thrombosis in the HeartMate II left ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33(1):12–22. [Multicenter Study.Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t].

Xie A, Phan K, Yan TD. Durability of continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices: a systematic review. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;3(6):547–56.

Boyle AJ, Jorde UP, Sun B, et al. Pre-operative risk factors of bleeding and stroke during left ventricular assist device support: an analysis of more than 900 HeartMate II outpatients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(9):880–8.

Crow S, John R, Boyle A, et al. Gastrointestinal bleeding rates in recipients of nonpulsatile and pulsatile left ventricular assist devices. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137(1):208–15.

Eckman PM, John R. Bleeding and thrombosis in patients with continuous-flow ventricular assist devices. Circulation. 2012;125(24):3038–47.

Slaughter MS. Hematologic effects of continuous flow left ventricular assist devices. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2010;3(6):618–24.

Uriel N, Morrison KA, Garan AR, et al. Development of a novel echocardiography ramp test for speed optimization and diagnosis of device thrombosis in continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices: the Columbia ramp study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(18):1764–75.

Tang GH, Kim MC, Pinney SP, Anyanwu AC. Failed repeated thrombolysis requiring left ventricular assist device pump exchange. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81(6):1072–4.

Birschmann I, Dittrich M, Eller T, et al. Ambient hemolysis and activation of coagulation is different between HeartMate II and HeartWare left ventricular assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33(1):80–7.

Katz JN, Jensen BC, Chang PP, et al. A multicenter analysis of clinical hemolysis in patients supported with durable, long-term left ventricular assist device therapy. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015;34(5):701–9.

Bartoli CR, Ghotra AS, Pachika AR, Birks EJ, McCants KC. Hematologic markers better predict left ventricular assist device thrombosis than echocardiographic or pump parameters. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;62(5):414–8.

Shah P, Mehta VM, Cowger JA, Aaronson KD, Pagani FD. Diagnosis of hemolysis and device thrombosis with lactate dehydrogenase during left ventricular assist device support. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33(1):102–4.

Gunduz H, Akdemir R, Binak E, Tamer A, Uyan C. Relation between stage of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and QT dispersion. Acta Cardiol. 2003;58(4):303–8.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Akin, S., Soliman, O., Constantinescu, A. et al. Haemolysis as a first sign of thromboembolic event and acute pump thrombosis in patients with the continuous-flow left ventricular assist device HeartMate II. Neth Heart J 24, 134–142 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12471-015-0786-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12471-015-0786-2