Abstract

Objectives

Analysis of the first results of off-site percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) and fractional flow reserve (FFR) measurements at VieCuri Medical Centre for Northern Limburg in Venlo.

Background

Off-site PCI is accepted in the European and American Cardiac Guidelines as the need for PCI increases and it has been proven to be a safe treatment option for acute coronary syndrome.

Methods

Retrospective cohort study reporting characteristics, PCI and FFR specifications, complications and 6-month follow-up for all consecutive patients from the beginning of off-site PCI in Venlo until July 2012. If possible, the data were compared with those of Medical Centre Alkmaar, the first off-site PCI centre in the Netherlands.

Results

Of the 333 patients, 19 (5.7 %) had a procedural complication. At 6 months, a major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) occurred in 43 (13.1 %) patients. There were no deaths or emergency surgery related to the PCI or FFR procedures. There was no significant difference in occurrence of a MACE or adverse cerebral event between the Alkmaar and Venlo population in the 30-day follow-up.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates off-site PCI at VieCuri Venlo to have a high success rate. Furthermore, there was a low complication rate, low MACE and no procedure-related mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The number of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs) has increased worldwide [1], as PCIs are widely accepted as a safe treatment option for stable angina and acute coronary syndrome (ACS) [2, 3]. This increase is caused in part by demographic reasons (ageing population) and lifestyle choices increasing cardiovascular risk [4]. The need for urgent cardiac surgery due to complications of PCIs has decreased since the introduction of coronary stents, better techniques, and improved antiplatelet drugs [2, 3, 5–7].

To meet the increase in need for PCIs, it was proposed to start PCIs at hospitals that do not have on-site facilities for cardiac surgery back-up, so-called off-site PCIs. Initially, the American cardiac societies advised against off-site (non-primary) PCIs [8, 9], but this was adjusted after numerous studies showed it to be safe [10–18]. In the Dutch and British Guidelines off-site PCIs have been accepted for some time now [19, 20]. However, off-site centres do require high operator and institutional volumes, as well as a proven, tested plan for rapid transport to a nearby hospital with cardiac surgical capability [18–20]. A good collaboration with cardiac surgeons, with regular heart team meetings between cardiac surgeons and cardiologists is another key factor for success of off-site PCI [12]. Despite this, there are also contradicting results showing off-site PCIs to have a higher mortality [21].

The delay in the treatment of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients should be 90 min or less [22, 23]. This should be achieved in the Netherlands in 90 % of the STEMI patients [24]. In the Venlo area, this goal is only reached in about 60 % [25].

Off-site PCI started in the Netherlands in 2003. The Medical Centre Alkmaar (MCA) was designated by the Dutch Government as a trial off-site PCI centre [12]. After the success of this PCI centre, 14 other Dutch hospitals started performing off-site PCIs. VieCuri Medical Centre for Northern Limburg in Venlo started off-site PCIs in 2011, firstly driven to shorten the delay in treatment of STEMI patients [26].

In this article we report the first results of off-site PCI and fractional flow reserve (FFR) measurement at our institution.

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort study from the start of PCIs at VieCuri Venlo in September 2011 until July 2012.

All patients scheduled for a PCI and/or FFR procedure at VieCuri Venlo were included. Patients undergoing FFR measurements were also included, as the complications of these patients can be similar [4, 27, 28]. No patients were excluded after scheduling. The data of our study were, if possible, compared with data from MCA [12].

PCI and FFR procedures

Patients were scheduled for a PCI and/or FFR procedure in Venlo if they had ischaemic coronary artery disease. Ischaemic coronary artery disease was defined as angina with proven myocardial ischaemia or ACS. All indications were discussed and agreed on by the Heart Team, led by an interventional cardiologist and a cardiothoracic surgeon, from Maastricht University Medical Centre (MUMC), by using an advanced webviewer (Evocs®, Fysicon, the Netherlands). Emergency (surgical) back-up was also arranged via MUMC.

Patients did not undergo the procedure in Venlo if they were eligible for PCI but classified as ‘high risk’. These patients were sent to a tertiary hospital and were (mostly) patients with unprotected left main artery vessel disease or 3-vessel coronary disease. In our first year most patients in need of primary PCI were sent to Catharina Hospital Eindhoven (CZE). No patients were sent for rescue PCI, as thrombolysis is no longer a treatment option for ACS in the Netherlands.

The choice for drug-eluting or bare-metal stent, intravascular ultrasound and intra-aortic balloon pump was left to the discretion of the interventional cardiologist. Rotablation was not available in our hospital.

During the procedure, patients were given intravenous heparin. All patients were treated with double antiplatelet therapy.

Data and outcome measures

Baseline characteristics, PCI and FFR characteristics and complications were retrospectively found in medical records. Lesion types are given according to the guidelines [29].

The primary endpoint of this study was major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) at 6 months, a combined endpoint of mortality, myocardial infarction (MI) and/or revascularisation. The secondary endpoint was major adverse cardiovascular and cerebral events (MACCE) at 6 months, including (non-)cardiac mortality, (non-)target vessel MI, target, non-target or FFR vessel re-PCI, emergency or semi-elective coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), and ischaemic or haemorrhagic cerebrovascular accident, major or minor bleeding described by the thrombolysis in myocardial infarction bleeding criteria (TIMI) [30] and the need for blood transfusion. Follow-up was found in medical records or acquired through the general practitioner.

Only elective PCIs were compared between Venlo and Alkmaar as the study from Alkmaar included patients who underwent PCI (and not FFR measurement), and our study primarily consisted of elective PCIs. As Alkmaar only started elective PCIs in their second year, our first-year results are compared with their second-year results. The endpoints are compared at 30-day follow-up.

Data analysis

Data were collected and analysed by an independent investigator in SPSS version 19. Frequencies, means and medians were calculated and the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the results of the two hospitals. A p-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

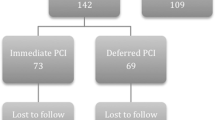

A total of 333 patients underwent a PCI and/or FFR procedure in the study period at VieCuri. In these patients 330 lesions were treated with PCI and 143 lesions were evaluated with FFR. No patients were excluded.

Characteristics

Baseline characteristics including risk factors and comorbidities are summed up in Table 1. All characteristics were normally distributed among the PCI and FFR groups. A P2Y12 inhibitor was prescribed in 94.0 % of the patients. In the group of patients who underwent a PCI, a P2Y12 inhibitor was prescribed in 100 % of the patients before the procedure.

Angiographic characteristics

Of the 257 PCIs, 23 were primary PCIs. Overall, the procedures were successful in 94.9 % of the patients. Multi-vessel PCI was performed in 26 patients. The patients with 4 lesions all had at least one FFR measurement.

The procedure was unsuccessful in 20 cases. This was mostly due to failure to cross the lesion with a wire or the need for rotablation. Causes for the inability to pass a wire across the lesions were small vessels, extensive calcifications or ≥90˚ bends in the vessels. Lesion types were as followed: type A 25.2 %, type B1 20.1 %, type B2 31.1 % and type C 23.7 %.

Further angiographic characteristics are mentioned in Table 2.

Procedural complications

In total, 19 (5.7 %) patients had a procedural complication.

In three patients PCI was complicated by no-reflow. The first patient had a PCI of a venous graft and suffered an inferior MI due to no-reflow. No embolic protection device was used, as it was judged not necessary in this patient. In the other two patients, no-reflow in native vessels during PCI was accepted and treated conservatively. One of these patients suffered from a non-STEMI, the other had a minimal isolated rise in troponin.

No patients died due to a complication of the procedure or required cardiac surgery as a result of the procedure. One patient did, however, require surgery at the arterial access site due to excessive bleeding. The median fluoroscopy time was 7.13 min This was longer during PCIs then during FFR procedures (7.27 vs. 4.26 min) and the longest in patients who required both FFR measurement and PCI (10.41 min).

There were 32 (9.6 %) patients with minimal bleeding. This was not defined as a complication. In Table 3 an account of the complications in the study population is given.

Follow-up at 6 months

At the 6-month follow-up a MACE occurred in 43 (13.1 %) patients. In the follow-up period of 6 months, seven patients died. None of the deaths were related to the PCI or FFR procedures.

Among the seven deaths, there were three non-cardiac deaths. One patient died of severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The second patient died of cerebral haemorrhage (using double antiplatetet therapy) and the third patient died of hypoxic respiratory failure due to pneumonia. The other four patients had cardiac-related deaths. In two patients, admitted with severe haemodynamic instability due to acute MI, primary PCIs were performed in our hospital as transportation to CZE was judged impossible. Neither of these patients had had a PCI before this event. One of these patients suffered from a massive subacute anterior wall MI. Despite thrombosuction and stent placement during PCI, the flow was not restored. The patient developed pneumonia and died 2 days later. The other patient suffered from an inferior MI with expansion to the right ventricle. Coronary flow was restored during PCI. However, the patient had pulseless electrical activity on the intensive care unit during hypothermia treatment despite pacing and medication. The third cardiac-related death was a patient who died due to a posterior wall rupture during weaning from the heart-lung machine after mitral valve surgery for endocarditis. The former PCI was a work-up before surgery. The last patient, with an extensive history including pulmonary disease and a recently operated rectal carcinoma, died after resuscitation for sudden bradycardia followed by asystole. This happened 4 months after bare-metal stent implantation for diffuse stenosis of the right coronary artery. The family did not consent to autopsy.

All bleeding during follow-up was of gastrointestinal origin (Table 4).

Characteristics and follow-up compared with MCA

When comparing the populations from Venlo and Alkmaar, most characteristics and specifications did not differ significantly. However, the Alkmaar population had significantly more patients with two lesions and significantly less patients with one lesion (Table 5).

The 30-day MACCE-free survival is not significantly different between the Venlo and Alkmaar populations. The other endpoints did not occur enough to compare statistically (Table 6).

Discussion

This study reports the first results of off-site PCI and/or FFR procedures in Venlo. The results show a low occurrence of complications and MACE resulting in a successful early outcome of off-site PCIs.

In the study population 19 (5.7 %) patients suffered from a procedural complication. In the 6-month follow-up a MACE occurred in 43 (13,1 %) patients, mostly re-PCI. Only seven patients died. None of the deaths were directly related to the PCI or FFR procedure. The success rate was high at 94.9 %.

Patients who underwent FFR without subsequent PCI were either proven to have significant 3-vessel disease by FFR evaluation and considered eligible for CABG, or were proven to have no significant vessel disease at all.

For the first stage of off-site PCIs at VieCuri it was decided to perform only elective PCIs. Despite this, 23 primary PCIs were performed in the study period, mostly because the condition of the patients was judged to be too critical for transportation to a tertiary hospital. Two of these patients died within 2 days due to the extent and complications of the acute MI. Around-the-clock intervention of primary PCIs will be introduced in a second stage after which the delay in STEMI patients in our region is expected to be significantly reduced as transportation to a tertiary centre is no longer needed. The goal of 90 % of the patients within 90 min should be achieved when primary PCIs are introduced in the Venlo area [25].

As all patients scheduled for a PCI with stent placement require a P2Y12 inhibitor [18], analysis of prescribed medication in our study population was performed. In total 94.0 % of the patients received a P2Y12 inhibitor. All of the 20 patients not receiving a P2Y12 inhibitor only had a FFR measurement performed. There were two reasons why these patients did not receive a P2Y12 inhibitor. They were either scheduled for a diagnostic coronary catheterisation during which the interventional cardiologist decided to evaluate a moderate stenosis with FFR, or they were scheduled for CABG and further evaluation of a moderate stenosis was needed.

When comparing the elective PCIs of this study with the elective PCIs of the first off-site PCI centre, Alkmaar, most baseline characteristics and PCI specifications are not significantly different. However, a significant difference is the number of lesions per patient. This can partly be explained by the fact that we compared our first-year data to their second-year data. At the start of the off-site PCIs in Venlo it was decided to perform high-risk procedures at a tertiary hospital. Excluding high-risk patients from treatment at an off-site PCI centre is recommended by the Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions [9]. However, more high-risk procedures could be performed in Venlo as numerous studies have shown acceptable outcomes in high-risk patients [12–14, 31].

The 30-day follow-up in the two study groups does not differ significantly, thus showing the early outcome of off-site PCI at Venlo to be as successful as Alkmaar.

Limitations

As this is a retrospective study, not all data could be obtained. Also, not all our data could be compared with the study population from Alkmaar as the studies looked into different baseline characteristics and specifications of the PCI procedures. We did not compare our data to an on-site PCI centre.

Conclusion

This study reports the outcome of the first stage of off-site PCIs and FFR measurements at VieCuri Medical Centre for Northern Limburg in Venlo. It demonstrates that, though in a limited patient group, off-site PCI at VieCuri Venlo has a high success rate. Furthermore it shows a low complication rate, low MACE and no procedure-related mortality.

References

Maier W, Windecker S, Boersma E, et al. Evolution of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty in Europe from 1992–1996. Eur Heart J. 2001;22(18):1733–40. PubMed PMID: 11511123.

Yang EH, Gumina RJ, Lennon RJ, et al. Emergency coronary artery bypass surgery for percutaneous coronary interventions: changes in the incidence, clinical characteristics, and indications from 1979 to 2003. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(11):2004–9. PubMed PMID: 16325032.

Seshadri N, Whitlow PL, Acharya N, et al. Emergency coronary artery bypass surgery in the contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention era. Circulation. 2002;106(18):2346–50. PubMed PMID: 12403665.

Miller LH, Toklu B, Rauch J, et al. Very long-term clinical follow-up after fractional flow reserve-guided coronary revascularization. J Invasive Cardiol. 2012;24(7):309–15. PubMed PMID: 22781467.

Karvouni E, Katritsis DG, Ioannidis JP. Intravenous glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists reduce mortality after percutaneous coronary interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(1):26–32. PubMed PMID: 12570940.

McGrath PD, Malenka DJ, Wennberg DE, et al. Changing outcomes in percutaneous coronary interventions: a study of 34,752 procedures in northern New England, 1990 to 1997. Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34(3):674–80. PubMed PMID: 10483947.

Tamburino C, Russo G, Nicosia A, et al. Prophylactic abciximab in elective coronary stenting: results of a randomized trial. J Invasive Cardiol. 2002;14(2):72–9. PubMed PMID: 11818641.

Smith SC, Dove JT, Jacobs AK, et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guideline and the Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions (Committee to Revise the 1993 Guidelines for Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty); ACC/AHA Guidelines for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (Revision of the 1993 PTCA Guidelines) - executive summary. Circulation. 2001;103(24):3019–41.

Dehmer GJ, Blankenship J, Wharton Jr TP, et al. The current status and future direction of percutaneous coronary intervention without on-site surgical backup: an expert consensus document from the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2007;69:471–8.

Aversano T, Aversano LT, Passamani E, et al. Thrombolytic therapy vs primary percutaneous coronary intervention for myocardial infarction in patients presenting to hospitals without on-site cardiac surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2002;287:1943–51.

Melberg T, Nilsen DWT, Larsen AI, et al. Nonemergent coronary angioplasty without on-site surgical backup: a randomized study evaluating outcomes in low-risk patients. Am Heart J. 2006;152:888–95.

Peels JOJ, Hautvast RWM, de Swart, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention without on site surgical back-up; two-years registry of a large Dutch community hospital. Int J Cardiol. 2007;132:59–65.

Ting HH, Raveendran G, Lennon RJ, et al. A total of 1,007 percutaneous coronary interventions without onsite cardiac surgery: acute and long-term outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(8):1713–21. PubMed PMID: 16631012.

Zavala-Alarcon E, Cecena F, Ashar R, et al. Safety of elective–including “high risk”–percutaneous coronary interventions without on-site cardiac surgery. Am Heart J. 2004;148(4):676–83. PubMed PMID: 15459600.

Singh PP, Singh M, Bedi US, et al. Outcomes of nonemergent percutaneous coronary intervention with an without on-site surgical backup: a meta-analysis. Am J Ther. 2011;18:22–8.

Wharton TP. Nonemergent percutaneous coronary intervention with off-site surgery backup; an emerging new path tot access. Crit Path Cardiol. 2005;4(2):98–106.

Paraschos A, Callwood D, Wightman MB, et al. Outcomes following elective percutaneous coronary intervention without on-site surgical backup in a community hospital. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95(9):1091–3. PubMed PMID: 15842979.

Levine G, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:44–112.

Nederlandse Vereniging voor Cardiologie: Dutch guidelines for interventional cardiology; Institutional and operator competance and requirements for training. 2004.

Dawkins KD, Gershlick T, de Belder M, et al. Joint Working Group on Percutaneous Coronary Intervention of the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society and the British Cardiac Society; Percutaneous coronary intervention: recommendations for good practice and training. Heart. 2005;91:1–27.

Wennberg DE, Lucas FL, Siewers AE, et al. Outcomes of percutaneous coronary interventions performed at centers without and with onsite coronary artery bypass graft surgery. JAMA. 2004;292(16):1961–8. PubMed PMID: 15507581.

Task Force on the management of STseamiotESoC, Steg PG, James SK, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(20):2569. PubMed PMID: 22922416.

O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2012 Dec 17. PubMed PMID: 23247304.

Piek JJ, Aengevaeren WR, Appelman Y, et al. Praktijkgids Optimale Zorg bij Acute Coronair Syndroom: VMSzorg. 2010.

Mol KA, Meeder JG, Duygun A, et al. Treating ST-elevation myocardial infarction within 90 minutes in the Netherlands: goal not yet achieved. 2013. [Submitted].

www.nvvc.nl. [homepage from the internet]. Witte lijsten PCI. Nederlandse Vereninging voor Cardiologie; 2013 [25-02-2013]. Available from: https://www.nvvc.nl/witte-lijsten.

Puymirat E, Peace A, Mangiacapra F, et al. Long-term clinical outcome after fractional flow reserve-guided percutaneous coronary revascularization in patients with small-vessel disease. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5(1):62–8. PubMed PMID: 22319067.

Tonino PA, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, et al. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(3):213–24. PubMed PMID: 19144937.

Ryan TJ, Faxon DP, Gunnar RM, et al. Guidelines for percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Assessment of Diagnostic and Therapeutic Cardiovascular Procedures (Subcommittee on Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty). Circulation. 1988;78(2):486–502.

Chesebro JH, Knatterud G, Roberts R, et al. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Trial. Phase I: a comparison between intravenous tissue plasminogen activator and intravenous streptokinase. Clinical findings through hospital discharge. Circulation. 1987;76(1):142–54. PubMed PMID: 3109764.

Frutkin AD, Mehta SK, Patel T, et al. Outcomes of 1,090 consecutive, elective, nonselected percutaneous coronary interventions at a community hospital without onsite cardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(1):53–7. PubMed PMID: 18157965.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. J.O.J. Peels for providing the data from the Medical Centre Alkmaar.

Funding

None.

Conflict of interests

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Mol, K.A., Rahel, B.M., Eerens, F. et al. The first year of the Venlo percutaneous coronary intervention program: procedural and 6-month clinical outcomes. Neth Heart J 21, 449–455 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12471-013-0447-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12471-013-0447-2