Abstract

This study examines the effects of social media use on anxiety levels of Australian Jews during the 5-week post-October 7 aftermath. It considers this relationship in the context of the mediating roles played by concerns about rising antisemitism in Australia and concerns about Israel. It further examines the moderating effects on these relationships of non-Jewish friends reaching out with messages of sympathy and concern, and the effects of Jewish communal ties. The analysis is based on data collected from 7611 Australian Jewish adults and employs a series of ordinary least squares regression analyses to assess the direct, indirect, and interaction effects of these variables on anxiety. The results indicate significant direct effects of social media use on anxiety levels. Additionally, concerns about antisemitism in Australia and concerns about Israel were found to mediate these relationships. Non-Jewish friends reaching out frequently with messages of sympathy and concern was found to attenuate the effects of concerns about antisemitism in Australia on anxiety. By contrast, Jewish communal ties were not found to significantly moderate the effects of concern about Israel on anxiety. These findings underscore the complex interplay between social media use, concern about local antisemitism, concern about Israel, and forms of social support in shaping anxiety levels of Australian Jews during this particular time period. The implications for mental health of ethnoreligious groups during crisis and avenues for future research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The events of October 7, 2023, in Israel, and the ensuing war between Israel and Hamas, alongside spikes in antisemitism across diaspora Jewish communities, were sources of great trauma and shock. The combination of shock, concerns about Israel and its people during the evolving war, together with growing concern for their own safety, suggested that many Australian Jews were experiencing elevated levels of fear and anxiety during this particular time period. An Internet-based survey fielded between November 10 and 17 2023 (n = 7611), the fifth week of the October 7 aftermath, provides data to empirically assess the impact of the Israel−Hamas war on Australia’s Jewish community (Bankier-Karp and Graham 2024). Several variables in this dataset were employed to examine in detail the relationship between social media use and anxiety among Jews in Australia. These variables included concern about antisemitism in Australia, concern about Israel, whether non-Jewish friends had reached out with messages of sympathy and concern, and the type of Jewish communal ties held. These variables were conceptualized in two moderated mediation models to examine the effects of social media use and measures of concern and support on the anxiety of Australian Jewish adults.

Israel−Hamas War Background Events

At 06:26 am on October 7, 2023, coinciding with the Jewish festival of Simchat Torah, armed Hamas militants breached the Gaza security fence in a coordinated surprise attack, invading southern Israel by land, air, and sea (Bergman and Zeiton 2023). Israeli towns, Israel Defense Forces bases, and the Nova Music Festival in a forest next to Kibbutz Re’im were targeted. More than 1200 Israelis were murdered, over 240 were abducted and taken into Gaza, and many women were sexually assaulted (Shyman 2023). The attack was followed by an unprecedented, large-scale air and ground assault on Hamas in Gaza by Israel, in an operation named Swords of Iron.

Post-October 7 in Australia: Background Events

News of the October 7 events reached Australian shores quickly, the shocked Jewish community combing social media for information that might confirm if loved ones had been killed, abducted or spared (Panagopoulos et al. 2023:3). For Australian Jews, the events of October 7 were personal. Seven percent of the Jewish population is Israeli-born (Graham 2024). In addition, the majority (82%) of Australian Jews have family and/or friends in Israel, have visited the country at least once (87%), and describe themselves as very much attached to Israel (75%) (Bankier-Karp and Graham 2024).

Jewish communal leaders received notification on October 9 2023 that the iconic Opera House would be lit up in the blue and white colors of the Israel flag, in an act of governmental support. That night, however, the Sydney Jewish community was advised to remain at home, because a group of pro-Palestinian protestors had moved from the Town Hall to the Opera House to continue their demonstrations (Wu 2023). Media footage from that event captured Israeli flags set on fire, Hamas flags waved, and menacing chants uttered (Demetriadi and Panagopolous 2023). That day, an Islamic sheikh also declared before an assembled crowd on the streets of Melbourne that October 7 was a “day of pride” that made him “elated” (Demetriadi 2023) and a series of Islamic preachers were exposed over subsequent days as praising the events of October 7 and rallying congregants to the cause. During the course of the next few weeks, the spike in antisemitism, including intimidatory, pro-Hamas demonstrations, precipitated elevated levels of fear among Australian Jews for their personal safety (McCracken and Rivera 2023).

To understand the emotional responses of Australian Jews to October 7, it is illustrative to consider their responses to three questions asked both in the immediate October 7 aftermath and 5 years prior. In 2017, a minority of Australian Jews regarded antisemitism to be a “very big” (6%) or “fairly big” (38%) problem in Australia (Graham and Markus 2018). In the fifth week of the war following the October 7 attacks, Australian Jews had changed their views considerably, with far more regarding antisemitism as a “very big” (64%) or “fairly big” (28%) problem (Bankier-Karp and Graham 2024). These findings are further corroborated by a study of online antisemitism which reported a 539% increase in online antisemitism compared with the year prior to October 7, 2023 (Oboler et al. 2024).

A hypothetical question was posed to Australian Jews in the 2017 study, asking what would best describe how they felt if international events were to put Israel in danger. The highest response option—“my reaction is so strong that it is almost as if my own life was in danger”—was selected by 16% of Australian Jews (Graham and Markus 2018). In the October 7 aftermath, 37% indicated they felt as if their own lives were in danger, that proportion more than doubling (Bankier-Karp and Graham 2024).Footnote 1

It is also the case that the consumption of news about Israel by Jews dramatically increased. For example, in 2017, smaller shares of Australian Jews indicated they were following news in Israel very (30%) or somewhat (67%) closely, while post October 7, almost all (98%) Australian Jewish adults were following the Israel−Hamas war very (79%) or fairly (19%) closely (Bankier-Karp and Graham 2024). Further, eight in ten (81%) Jews said they were talking about the war with friends and family in Australia, and more than six in ten (64%) Jews said they talked about the war with family and friends in Israel. While mainstream Australian media sources were consumed “most frequently” by Australian Jews (68%), this was closely followed by social media (67%) and Israeli news sources (63%) (Bankier-Karp and Graham 2024).

In addition to these findings, the post-October 7 survey also showed that 44% of Jews said that they were “feeling nervous anxious or on edge” on a daily basis, with a further 38% saying this was the case “frequently but not daily.” In addition, 31% said that they were “not able to stop or control worrying” on a daily basis, with a further 36% saying this was the case “frequently but not daily” (Bankier-Karp and Graham 2024). These proportions far exceed what might be expected given data on anxiety from the general population, which suggests that the combination of shock at the events of October 7, concerns about the safety of relatives and friends in Israel, and growing concern for their own safety in Australia caused many Australian Jews to exhibit elevated levels of fear and anxiety. While a range of factors play a role in influencing such feelings, understanding the interconnected effects of social media use, sources of concern, and social support on anxiety is helpful to better appreciate the experience of many Australian Jews during this period.

Anxiety and the Influence of Social Media, Sources of Concern and Social Support

High-volume social media use has been found to be associated with measures of poor mental health, including depression and anxiety (Haidt 2024; Lin et al. 2016). A systematic review and meta-analysis have confirmed social media to be significantly and strongly predictive of adverse mental health outcomes (Purba et al. 2023). Other research, however, suggests that it is the quality or nature of social media use, not the length of time spent consuming it, which causes poor mental health. How individuals perceive or experience social media seems to be the more salient factor in determining its impact rather than the sheer volume of use or exposure (Shensa et al. 2018).

However, it is also evident that the relationship between social media use and mental health may well be more complicated than this. In addition to research that has identified direct negative effects, other studies have reported social media to have indirect negative effects, or mediating effects, on mental health via other emotional stressors such as fear of COVID-19 (Tillman et al. 2023). However, social media use has not ipso facto been found to have only adverse effects on mental health. A longitudinal study and systematic review have reported that social media use does not correlate with depression and anxiety and, in fact, may even contribute to social capital and heightened life satisfaction, potentially safeguarding against symptoms of depression and anxiety (Hall et al. 2019; Seabrook et al. 2016). Further, recent studies have shown that people who are skilled communicators, who have greater communication capacity—the ability to clearly receive and convey information, effectively express thoughts, emotions and opinions, and accurately interpret the feelings and views of others—has also been reported to have positive moderating effects on the relationship between social media use and anxiety (Lai et al. 2023). An Australian mental health study has reported that problematic social media use is associated with anxious attachment, mediated by fear of missing out and moderated by high life satisfaction (Boustead and Flack 2021), suggesting the influence of a range of interconnected variables on anxiety. Indeed, fears and concerns are highly predictive of anxiety (Öhman 2008).

Demographically, aging is generally associated with better mental health (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2024; Ferraro and Wilkinson 2013) and males generally have better mental health than females (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2023; Rosenfield and Mouzon 2013). There is less of a consensus regarding the effect of education on mental health, with some studies reporting that more years of education are associated with superior mental health (Kondirolli and Sunder 2022), while twin studies—which control for the influence of genetic traits and shared family characteristics—conclude that any observed associations between education and mental health are attributable to unobserved variables, not education (Halpern-Manners et al. 2016).

Social ties have long been identified as safeguarding against poor mental health (Pew Research Center 2019; Waldinger and Schulz 2023). From the earliest sociological studies, lack of social integration has been identified as highly predictive of suicide (Durkheim 1897/2005) and, conversely, friendship has been deemed the “vaccine” against mental illness (King et al. 2017). Similarly, religiosity also correlates with better mental health (Bankier-Karp and Shain 2021), whereas negative religious views and feelings have been associated with increased anxiety (Rosmarin and Leidl 2020). Positive religious coping—the use of religion for seeking resilience and guidance during challenging times—has been shown to help alleviate distress and circumvent associated negative thoughts (Pargament et al. 2005). It follows that, when one’s social group or community is religious in nature, the benefits of social cohesion and religiosity combine to create a potentially powerful source of support and mental fortitude (Fredrickson 2002).

Hypotheses

The cited social-psychological literature on mental health predictors guides the following two hypotheses:

H1

The direct effect of social media use on generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (henceforth anxiety) will be significant and positiveFootnote 2 specifically, Australian Jews who increased their social media use will have exhibited increased levels of anxiety compared with those who did not do so (i.e. abstaining from, decreasing or not changing social media use during the 5-week post-October 7 period). In addition, the indirect and positive effects of social media use on anxiety will be greater when concern about antisemitism in Australia (henceforth concern about antisemitism) and concern about Israel are heightened. Specifically, the relationship between social media and anxiety will be mediated by concerns about antisemitism and Israel, these increased concerns intensifying the impact of social media use on anxiety.

H2

The relationship between social media and anxiety will be moderated by two sources of social support; namely those of non-Jewish friends who reached out with messages of sympathy and concern (henceforth non-Jewish friends) during the 5 weeks post October 7, and Jewish communal ties. Specifically, non-Jewish friends frequently reaching out to express sympathy or concern and type of communal ties will attenuate social media’s effect on anxiety. In other words, social interactions with sympathetic non-Jews and more religiously Jewish communal ties will have attenuating effects on the relationship between social media use and anxiety. However, non-Jewish friends and the type of Jewish communal ties will also interact with concern about antisemitism in Australia and concern about Israel meaning that non-Jewish friends who reached out frequently with messages of sympathy and support, and more religious Jewish communal ties will have attenuating effects on the direct and indirect relationships between social media use and anxiety.

Method

Data

The purpose of the research was to conduct an empirical assessment of the impact of the Israel−Hamas war on Australia’s Jewish community. Ethics approval was granted for this research (Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee Project 40,944). A committee comprising the primary investigators and Jewish community leaders was formed to develop the survey instrument. Three main sources were drawn upon for the development of the survey instrument. First, the Gen17 Australian Jewish Community Survey (Graham and Markus 2018) instrument was utilized for items relating to perceptions of antisemitism and measures of Israel attachment. Secondly, the In the Shadow of War: Hotspots of Antisemitism on US College Campuses (Wright et al. 2023) instrument, developed by the Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies, Brandeis University, was utilized for items relating to views about the Israel−Hamas war, perceptions of antisemitism and Israel attachment. Thirdly, several novel questions were developed including emotional responses to the war, measures of anxiety, feelings about Jewish identity, and interactions with non-Jewish friends and acquaintances.

The Internet-based survey was fielded between November 10 and 17, 2023, the fifth week post October 7, yielding a sample of 7611 Australian Jews ages 18 years and above out of a population of an estimated 92,000 adults (Graham 2024). A survey link was circulated by Jewish communal organizations across Australia to their membership lists, which was further circulated by participants to other Australian Jews via private messaging. The survey was anonymous and promotion of the survey on public platforms and social media was strongly discouraged to minimize the potential risk of sabotage. Although characterized as a non-probability convenience sample owing to the recruitment methods, post-hoc weights developed using Australian Census data aligns the sample with the total population by age, sex, and state/territory. In addition, a comprehensive national synagogue membership census aligns the sample by denominational affiliation—an approach which is consistent with earlier Australian Jewish communal studies (Graham and Markus 2018)—making the dataset broadly representative of Australian Jewry. (For further information on survey methodology, see Bankier-Karp and Graham 2024: 44–48).

Measures

Consistent with the stated purpose of the research, a range of sociodemographic and Jewish identity variables were included in the survey instrument.

Independent Variables

The independent variables of interest measured social media use, concern about antisemitism, concern about Israel, non-Jewish friends, and Jewish communal ties. Social media use was the primary independent variable, concern about antisemitism in Australia and concern about Israel were proposed as mediators, and non-Jewish friends, and Jewish communal ties were proposed as moderators. Table 1 contains the descriptive statistics for the study variables.

Dependent Variable

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder two-item scale (GAD-2) is an established measure used in Australia and internationally for measuring the frequency of symptoms of anxiety (Staples et al. 2019; Wittchen and Jurgen 2001). An adapted version of the GAD-2 measured anxiety and comprises two questions. The summed scores of these two questions were used as the dependent variable in this analysis (Table 1).

Covariates

Given the influence of the three sociodemographic variables on mental health (mentioned earlier), age, sex, and education were assigned as covariates in this analysis, to partial out their effects. In addition, to ensure that effects of the two mediators—concern about antisemitism and concern about Israel—were each measured without the potential influence of the other, the mediator of the first analysis was included as a covariate in the second analysis, and vice versa (Table 1).

Analytic Approach

Seven separate analyses were conducted to examine the study hypotheses. The rationale for the variables and their location within the models was grounded in the relevant literature as well as the findings of a thematic analysis of the open-ended survey question in which respondents shared their views about their experiences relating to the Israel−Hamas war as a Jewish person living in Australia (Bankier-Karp and Graham 2024). The analytic approach was chosen for its rigor and capacity to examine the interconnected ways that the various experiences of Australian Jews impacted on their anxiety in the 5-week post-October 7 period. A series of OLS regression analyses was conducted, using Andrew Hayes’ (2017) SPSS macro for mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis.

First, the direct effect of social media use (X) on anxiety (Y) was examined using a bivariate regression (Fig. 1).

Secondly, the indirect effects of social media use (X) on anxiety (Y) were examined using OLS regression. Mediation analysis is a form of OLS regression analysis which identifies how a causal antecedent variable (in this analysis, social media use, X) influences an outcome variable (in this analysis, anxiety, Y) through one or more intervening or mediating variables (Hayes 2017). In this analysis, level of concern about antisemitism in Australia was operationalized as the mediator (M1) in mediation 1 (Fig. 2) and level of concern about Israel was operationalized as the mediator (M2) in mediation 2 (Fig. 3). This analysis tests the effect of each mediator on the primary relationship between social media use (X) and anxiety (Y). Hayes’ (2017) PROCESS macro model 4 was used to conduct this analysis. These procedures operationalized H1.

Thirdly, the effects of non-Jewish friends (W1) and Jewish communal ties (W2) were examined using OLS regression. Moderation analysis is a form of OLS regression analysis which identifies the boundary conditions of an effect, or the circumstances, catalysts, or types of people for whom a certain effect is large or small, present or absent, positive or negative (Hayes 2017). Moderation 1 examined the interaction effects of non-Jewish friends (W1) on the relationship between social media use (X) and anxiety (Y), predicting anxiety from social media use, non-Jewish friends, and their product (Fig. 4). Moderation 2 examined the interaction effects of Jewish communal ties (W2) on the relationship between social media use (X) and anxiety (Y), predicting anxiety from social media use, Jewish communal ties, and their product (Fig. 5). Hayes’ (2017) PROCESS macro model 1 was used to conduct this analysis.

The fourth and final step in the analysis was to examine the effects of concern about antisemitism (M1), non-Jewish friends (W1), concern about Israel (M2), and Jewish communal ties (W2) on the relationship between social media use and anxiety using moderated mediation analysis. Moderated mediation analysis combines mediation and moderation analyses. It is used when the research goal is to describe the boundary conditions of the mechanism(s) by which a variable transmits effects on another (Hayes 2017). This kind of analysis enables the identification of the direction of the cause and some of its boundary conditions, such as the type or category of people for whom this relationship would be expected to be larger or smaller. By modelling the relationships in this way, and acknowledging the more complex, interconnected interactions that are occurring, this approach can provide a more nuanced and realistic picture of the effects taking place. It is more informative and helpful when research can speak to more than just whether an effect exists, whether an effect is different from zero, or whether two groups differ from one another (Hayes 2017).

In moderated mediation model 1 (Fig. 6), the mediator—concern about antisemitism (M1)—was conceptualized as the mechanism through which social media use (X) indirectly influenced anxiety (Y). In addition, a moderator—non-Jewish friends (W1)—was conceptualized as interacting with the pathways between social media use (X), concern about antisemitism (M1), and anxiety (Y).

In moderated mediation model 2 (Fig. 7), the mediator—concern about Israel (M2)—was conceptualized as the mechanism through which social media use (X) indirectly influenced anxiety (Y). In addition, a moderator—Jewish communal ties (W2)—was conceptualized as interacting with the pathways between social media use (X), concern about Israel (M2), and anxiety (Y).

The analyses were conceptualized as fully mediated models with moderation of the direct effect, first, and second stages of an indirect effect across the mediator. Hayes’ (2017) PROCESS macro model 58 was used to conduct this analysis. The third and fourth statistical procedures operationalized H2.

For the latter three statistical analyses, the sociodemographic factors (age, sex, education, and the mediator of the alternate analysis) were included as covariates. Consistent with Hayes’ (2017) guidelines, the results of the analyses are depicted in statistical diagrammatic form.

Results

Bivariate Regression Analysis: The Impact of Social Media Use on Anxiety

H1 was that those who increased their social media use would have higher levels of anxiety compared with those who maintained, decreased or did not use social media. One simple linear regression was conducted to test this direct effect of social media use (X) on anxiety (Y) (Fig. 8). The bivariate regression was significant (β = 0.18, F[1, 7532] = 261.40, p < 0.001), indicating that increased use of social media was associated with increased anxiety. Increased social media use explained 3% of the variance in anxiety.

Mediation Analyses

H1 was that the relationship between social media use and anxiety is mediated by concern about antisemitism in Australia and concern about Israel. This hypothesis was tested using OLS regression. Mediation 1 testing the indirect effect of social media use (X) on anxiety (Y) through concern about antisemitism (M1), and mediation 2 testing the indirect effect of social media use (X) on anxiety (Y) through concern about Israel (M2).

Mediation 1: The Role Played by Concern about Antisemitism in Australia

As can be seen in Fig. 9 (the c1 path), social media has a direct and positive effect on anxiety (c1 = 0.11, p < 0.001) as social media use increased, so did anxiety (Appendix Table 3). Also, as can be seen in Fig. 9, social media use has an indirect and positive effect on anxiety via concern about antisemitism increased social media use was associated with the increased perception that antisemitism was a big problem in Australia (the a1 path and Appendix Table 3), which in turn was associated with increased anxiety (the b1 path and Appendix Table 3).

The bias-corrected bootstrap-confidence intervals (CIs) for the products of these paths that do not include zero provide evidence of a significant indirect effect of social media use on anxiety through concern about antisemitism. The two indirect effect pathways and the fully mediated indirect effect (β = 0.02, p < 0.001) were significant, as was the total effect (β = 0.13, p < 0.001).

Mediation 2: The Role Played by Concern about Israel

Figure 10 (the c2 path) indicates that social media has a direct and positive effect on anxiety (c2 = 0.11, p < 0.001) as social media use increased, so did anxiety (Appendix Table 4). Also evident in Fig. 10 is that social media use has an indirect and positive effect on anxiety via concern about Israel increased social media use was associated with increased concern about Israel (the a2 path and Appendix Table 4), which in turn was associated with increased anxiety (the b2 path and Appendix Table 4).

The bias-corrected bootstrap-confidence intervals (CIs) for the products of these paths that do not include zero provide evidence of a significant indirect effect of social media use on anxiety through concern about Israel. The two indirect effect pathways and the fully mediated indirect effect (β = 0.05, p < 0.001) were significant, as was the total effect (β = 0.16, p < 0.001).

Moderation Analysis

H2 was that the relationship between social media use and anxiety is moderated by non-Jewish friends and Jewish communal ties. This hypothesis was also tested using OLS regression. Moderation 1 tested the interaction between social media use (X) and non-Jewish friends (W1) on anxiety (Y). Moderation 2 tested the interaction between social media use (X) and Jewish communal ties (W2) on anxiety (Y).

Moderation 1: The Role Played by Non-Jewish Friends Reaching Out

The first moderation analysis tested whether the effect of social media use on anxiety was moderated by non-Jewish friends reaching out (Fig. 11). The interaction effect of social media on anxiety was not statistically significant (Fig. 11 and Appendix Table 5, Y and W1 columns).

Moderation 2: The Role Played by Jewish Communal Ties

The second moderation analysis tested whether the effect of social media use on anxiety was dependent on Jewish communal ties (Fig. 12) and revealed that the interaction accounted for 5% of the variance in anxiety (Appendix Table 5, Y and W2 columns).

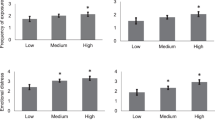

Once evidence of moderation—namely, a significant interaction effect—has been established, post-hoc testing enables further understanding of the parameters of the detected effect. One post-hoc test that probes these conditional effects is called the simple slopes analysis, also known as the pick-a-point approach or a spotlight analysis (Hayes 2017). In moderation 2, the conditional effect of social media use on anxiety was estimated using simple slopes analysis, with the sample mean, plus and minus one standard deviation from the mean representing non-Orthodox, Orthodox, and no-denomination types of Jewish communal ties, respectively. It shows that Jewish communal ties significantly and positively moderated the relationship between social media use and anxiety at all three points (the conditional effects were 1.19, 1.98, and 2.77 at low, moderate, and high values of Jewish communal ties, respectively). Figure 13 represents these interaction effects graphically, the attenuating effect of Jewish ties being greatest for the Orthodox (the dotted line), whose anxiety decreases as their social media use increases.

Moderated Mediation

H2 was that social media use, non-Jewish friends, and Jewish communal ties interact in influencing concern about antisemitism, concern about Israel, and anxiety. This hypothesis was tested using moderated mediation.

Moderated Mediation 1: The Roles Played by Non-Jewish Friends Reaching Out and Concern about Antisemitism in Australia

The direct effect of social media use on anxiety was confirmed as significant and positive in moderated mediation 1 (Fig. 15 and Appendix Table 6), as it was in the earlier regression analyses (Figs. 8, 9 and Appendix Table 3), confirming H1, that increased social media use is associated with increased anxiety. H1 was further confirmed by the finding in moderated mediation 1 that the relationship between social media use and anxiety was positively and significantly mediated by concern about antisemitism (Fig. 15, Appendix Table 6), as it was in the earlier mediation analysis (Fig. 9 and Appendix Table 3). The model coefficients (summarized in Appendix Table 6) also confirm the significance of the mediated pathways, as does mediation 1 (Fig. 9).

H2 relates the proposed moderation by non-Jewish friends of the impact of social media on concern about antisemitism (Fig. 15, a1 path) and anxiety (Fig. 15, b1 path). The conditional, direct, and indirect effects of social media use on anxiety were all significant (Appendix Table 7). Some moderating effects were significant—moderation of the second-stage mediation was significant (Fig. 15, b1 path); moderation of the first-stage mediation was not (Fig. 15, a1 path)—partly confirming H2. The conditional direct effect of social media use on anxiety was significantly moderated by non-Jewish friends, the interaction accounting for 2% of the variance in anxiety (Fig. 15).

Post-hoc testing was employed to test the parameters of the detected effects. The conditional effects of concern about antisemitism on the impact of social media use on anxiety (Fig. 14) were estimated using simple slopes analysis. Non-Jewish friends did not significantly moderate the relationship between social media use and concern about antisemitism (Appendix Table 6). Given that the interaction of non-Jewish friends was not significant, those whose non-Jewish friends reached out frequently had no significant moderating effect on their concern about antisemitism.

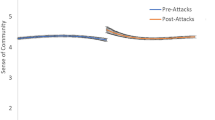

Non-Jewish friends reaching out did, however, significantly and negatively moderate the relationship between concern about antisemitism and anxiety at all three points (the conditional effects were 1.19, 1.99, and 2.77 at low, moderate, and high values of the frequency of non-Jewish friends reaching out, respectively; Appendix Table 6). Figure 14 represents these interaction effects graphically. With decreased or no concern about antisemitism, there are nonetheless differences between people with different levels of frequency of non-Jewish friends reaching out, in terms of their anxiety level. But as concern about antisemitism increased, anxiety in all groups increased. However, the significant interaction of non-Jewish friends meant that those whose non-Jewish friends reached out frequently (the dotted line) had a significant negative (i.e. attenuating) effect on their anxiety, even as their concern about antisemitism increased.

Moderated Mediation 2: The Roles Played by Jewish Communal Ties and Concern about Israel

The direct and indirect effects of social media use on anxiety were confirmed in the earlier regression analyses. The model coefficients (summarized in Appendix Table 8) demonstrate the significance of the mediated pathways, as do the earlier mediation analyses.

H2 relates to the proposed moderation by Jewish communal ties of the impact of social media on concern about Israel and anxiety. The conditional, direct, and indirect effects of social media use on anxiety were significant (Fig. 15 and Appendix Table 9). Some of the moderating effects were significant, partly confirming H2. The conditional direct effect of social media use on anxiety was significantly moderated by Jewish communal ties, the interaction accounting for 2% of the variance in anxiety.

The interaction effect of Jewish communal ties was not statistically significant (Fig. 15 and Appendix Table 9), meaning that Jewish communal ties did not significantly moderate the relationship between concern about Israel and anxiety (Fig. 15 and Appendix Table 9). Even with little to no social media use, there were noticeable differences between people with different types of Jewish communal ties in terms of their concern about Israel; those with Orthodox ties had the highest levels of concern about Israel, while the non-Orthodox and those with no denominational affiliation had lower levels of concern about Israel. But as concern about antisemitism increases, given that the interaction of Jewish communal ties was not significant, there was no moderating effect on anxiety irrespective of the type of Jewish communal ties.

Discussion

In the immediate aftermath of the war between Hamas and Israel which started on October 7, 2023, very high levels of anxiety were measured among Jews in Australia. The aim of this analysis has been to better understand the factors influencing this anxiety, more specifically, which factors intensify and which attenuate Australian Jewish people’s anxiety.

In doing so, and guided by the literature, two hypotheses were formulated.

H1, first, hypothesized whether Australian Jews who increased their social media use during the 5-week post-October 7 period would report higher levels of anxiety. This part of H1 was confirmed. H1 also asked whether the relationship between social media use and anxiety would be mediated by people’s concern about antisemitism in Australia and their concern about Israel. This second part of H1 was also confirmed. In other words, the indirect effects of concerns about antisemitism in Australia and concern about Israel on the impact of social media use on anxiety were greater than the direct effects alone. If a person reported high levels of anxiety, this could therefore be attributed not simply to their social media use, but also to their concerns about antisemitism in Australia and Israel.

H2 hypothesized that non-Jewish friends reaching out and Jewish communal ties would moderate the relationship between social media use and anxiety. This part of H2 was partially confirmed. On the one hand, non-Jewish friends reaching out frequently with messages of sympathy and concern did not have a significant effect on the relationship between social media use and anxiety. On the other hand, having Orthodox Jewish communal ties was found to have a significant interaction effect on social media’s impact on anxiety.

In addition, H2 hypothesized that non-Jewish friends and Jewish communal ties would moderate social media’s effects on concerns about antisemitism in Australia, concerns about Israel and anxiety. This was partially confirmed. In moderated mediation 1, the moderation of the second stage of the indirect effects across the mediators was significant. Being supported by non-Jewish friends frequently reaching out significantly decreased the effect of concerns about antisemitism on anxiety. However, Jewish communal—namely, having Orthodox, compared with non-Orthodox or no denominational—ties did not significantly moderate the effect of concerns about Israel on anxiety.

H2 was also not supported by two other findings, both being moderation of the first stages of the indirect effect across the mediators. The first of these findings is that non-Jewish friends reaching out with messages of sympathy and concern did not significantly interact with social media’s impact on concerns about antisemitism. In other words, increased social media usage increases concern about antisemitism regardless of whether or how often non-Jewish friends reached out. Secondly, having Orthodox Jewish communal ties did not significantly interact with social media use’s impact on concern about Israel—increased usage of social media increases concern about Israel regardless of the type of Jewish communal ties. When it came to both moderated mediation analyses, the conditional indirect effect of social media on anxiety was significantly larger than the direct effect of social media on anxiety. In other words, there is greater explanatory power in understanding the effects of social media use on anxiety when one includes sources of concern and support in the same model.

The Contribution of Social Media

The finding that social media use contributes significantly to anxiety for Australian Jews in the immediate October 7 aftermath supports the literature affirming the deleterious effect of social media on mental health (Lin et al. 2016). The positive statistical association confirms that the effect is cumulative, with increasing social media use leading to higher levels of anxiety (Purba et al. 2023). It is intuitive that increased social media use during a period when there was a 539% increase in antisemitism on social media (Oboler et al. 2024) would contribute to people’s anxiety. The statistically significant but small effects reported in this analysis echo the findings of other social-psychological studies which employ similar statistical techniques (Boustead and Flack 2021). In the case of Australian Jews, social media provided an intensive immersion into the events of October 7 and its aftermath both in Israel and in Australia.

The Contribution of Concerns about Antisemitism in Australia and Israel

This study found that having concern about antisemitism in Australia and concern about Israel significantly and positively mediate the effect of social media use on anxiety. The use of mediation analyses extends understanding of how the consideration of sources of fear and concerns—in this analysis, relating to antisemitism in Australia and concern for Israel—better explain the relationship between social media use and anxiety (Boustead and Flack 2021; Öhman 2008). Moreover, the positive association suggests that the effect is cumulative, with increased social media use leading to greater concerns about antisemitism in Australia and greater concern about Israel, which in turn leads to higher levels of anxiety. The indirect effects of social media use on anxiety appear to derive from the ways that social media coverage immersively and graphically presented the events which occurred on October 7. It therefore makes sense that concern about antisemitism in Australia and concern about Israel would significantly and positively mediate—that is, increase—the impact of social media use on anxiety.

These findings are also supported by earlier research examining indirect effects of social media on mental health via other emotional stressors (Tillman et al. 2023). Given the strong Israel attachment of the majority of Australian Jews and the graphic nature of the coverage of the events of October 7 on social media in particular, these findings of high levels of anxiety among Australian Jews dovetail with research claiming that how people experience social media content—irrespective of the duration of that social media use—is the more salient factor contributing to anxiety (Shensa et al. 2018). That the explanatory power of concern about antisemitism in Australia and concern about Israel are so statistically similar—even when each analysis partials out the effect of the other—provides insight into the degree to which both the more immediate threat of antisemitism in Australia and threats to a country thousands of miles away are similarly perceived by many Jewish people in Australia as threatening to their own wellbeing.

The Contribution of Non-Jewish Friends and Jewish Communal Ties

The finding that non-Jewish friends reaching out moderates the mediated relationship between social media use and anxiety echoes the findings of social-psychological research attesting to the protective effects of social ties vis-à-vis mental health (Durkheim 1897/2005; King et al. 2017). Considering that many Australian Jews had been concerned or upset by the reactions of their non-Jewish friends (60%) and non-Jewish colleagues (48%)—and only 14% reported their non-Jewish friends and acquaintances had reached out frequently with messages of concern and support—it is understandable that supportive contact from non-Jews would have been so deeply appreciated. There is corroboration in the qualitative reflections of hundreds of Australian Jews who noted that “silence is deafening”, expressing dismay at the reticence of their non-Jewish friends and colleagues, outright rejections, and the loss of friendships (Bankier-Karp and Graham 2024).

Unlike the broadly negative, attenuating effect of non-Jewish friends on anxiety, Jewish communal ties had no moderating effects on anxiety. Post-hoc analysis reveals that those with Orthodox Jewish communal ties have lower anxiety regardless of their social media use, which may attest to the benefits of being in a community that shares positive religious beliefs (Pargament et al. 2005; Rosmarin and Leidl 2020), albeit during less traumatic time periods. However, Orthodox Jews also have much higher levels of Israel attachment and, as such, may feel more deeply affected by the events of October 7 and the aftermath. It is possible that co-presence in the October 7 aftermath may have offered not religious support (Fredrickson 2002) as much as enabling a collective sharing of anxiety, grief, and shock that countered the usually positive effects of religious community.

As per the earlier discussion of the significance of these sources of social support, it makes sense that non-Jewish friends would attenuate anxiety. Nevertheless, it is still striking that Jewish communal ties did not exercise a comparable effect. It is possible that it is the heartening impact of non-Jewish friends reaching out with messages of sympathy and concern that makes its attenuating effect on anxiety so strong. It is also possible that Orthodox Jewish communal ties were not moderating the effects of concerns about Israel on anxiety not due to an absence of support but rather due to close social ties sharing—and thereby intensifying—one another’s concerns about Israel during a time of shock and grief.

Taking All Factors into Consideration

This analysis aimed to examine the direct and indirect effects of social media use on anxiety. Drawing on the literature and a qualitative analysis of the survey’s open-ended responses, it was determined that concerns about antisemitism in Australia and concern about Israel were pathways through which social media impacted on anxiety. Given that the thematic analysis also suggested that the influence of non-Jewish friends reaching out and Jewish communal ties varied, the analysis aimed to examine whether and under what circumstances these social ties moderated the effect of social media use—as well as whether they moderated the two aforementioned mediators (concern about antisemitism and concern about Israel)—on anxiety. Finally, the analysis aimed to examine the interrelated influences of all the aforementioned variables on anxiety and for whom these effects were applicable.

Moderated mediation was therefore employed for the final analytic stage, integrating mediation and moderation to examine the proposed interrelatedness of the previously examined factors in the lives of Australian Jews in the immediate aftermath of October 7. What this revealed was that, as the frequency of non-Jewish friends reaching out increased, it exercised an attenuating effect on social media’s direct and indirect impact on anxiety. Jewish communal ties did not exercise a statistically significant moderating effect on social media’s direct and indirect impact on anxiety. While in the human mind disentangling and separately measuring these sources of concern and support is impossible, moderated mediation enables their effects to be tested separately, with concerns about antisemitism in Australia exercising a slightly greater impact on anxiety, compared with concerns about Israel. Moderated mediation also allows for these sources of concern and support to be tested within a unified model, the frequency with which non-Jewish friends reached out with messages of sympathy and concern exercising a stronger and attenuating effect on anxiety, unlike Jewish communal ties, which did not exercise a significant moderating effect.

Conclusion

The events of October 7 in Israel, the ensuing war in Gaza and concomitant spikes in antisemitism across diaspora Jewish communities were sources of great trauma and shock. A survey of Australian Jews carried out across 5 weeks after October 7 showed heightened levels of anxiety in the Jewish population (Bankier-Karp and Graham 2024). Both quantitative and qualitative data gathered in the survey indicated correlations between a range of variables and levels of anxiety. The aim of this analysis was to identify the interconnected effect of a range of variables on the anxiety of Australian Jews during this time period.

First, we found that increased use of social media led directly to increased anxiety among Jews. Secondly, we identified that concern about antisemitism in Australia and concern about Israel acted as mediators of this relationship, significantly exacerbating the effect that social media use had on anxiety. Thirdly, while we found that non-Jewish friends reaching out did not significantly moderate the effect of social media use on anxiety, we did find that Jewish communal ties did. However, when all of the variables of interest were brought together in the two moderated mediation models, almost all of the direct, indirect and interaction effects were found to be significant. In the first moderated mediation model, we established that non-Jewish friends frequently reaching out with messages of sympathy and concern attenuated the effect of concerns about antisemitism on anxiety. In the second moderated mediation model, we established that Jewish communal ties did not moderate the effect of concern about Israel on anxiety. While the benefits of non-Jewish friends reaching out with messages of support and concern are evident, the absence of any effects of Orthodox Jewish communal ties are, prima facie, less intuitive. Given that the data used in this analysis were gathered in the early weeks of the war, when the shock of the situation in Israel and the spike of antisemitism in Australia were still fresh and raw, it is possible that the normally beneficial effects of belonging to religious communities were undermined as people shared news, grief, and deep concerns with each other.

Our findings contribute to broader research on the impact of social media use on mental health, in this instance by focusing on an ethnoreligious population in Australia during a time of conflict. By holding concern about Israel constant while testing the indirect effects of concerns about antisemitism in Australia—and vice versa—we have been able to examine their independent effects on anxiety. That concern about antisemitism in Australia was similar to concern about Israel in terms of their indirect intensifying effects on anxiety contributes to research on ethnoreligious communities that are pained by threats to their wellbeing and safety in their home countries as much as they are pained by threats to the countries to which they have ethnoreligious ties. The finding that non-Jewish friends reaching out with messages of sympathy and concern had an attenuating effect on the anxiety of a group experiencing hatred is a finding that has relevance to the fields of social psychology and sociology. Finally, the finding that belonging to a religious community in a time of crisis did not have an attenuating effect on anxiety is a challenging contribution to the sociology of religion. Such a finding challenges the extensive research reporting the benefits of belonging to a religious community. Nonetheless, there is a need for further research on how religious communities and their leadership can better address issues related to anxiety in times of crisis.

The cross-sectional nature of this data is one of the limitations of this analysis. While identically worded questions were taken from the most recent national Jewish population study (Graham and Markus 2018), enabling some comparisons, the data are not longitudinal in nature and thus cannot be subjected to time series analysis. Another potential limitation lies in the way the mediators were conceptualized. The most fundamental component of any mediation model is a mechanism (M) through which at least part of the effect of the independent variable (X) on the dependent variable (Y) is transmitted. In addition to establishing the mediator as a transmitter, it is important to establish causality. While it is both grounded in the literature and intuitive that social media use leads to increased concerns such as those measured in this analysis, we acknowledge that the mediation effect may have been bidirectional, meaning that social media use may have been both a cause and a consequence of people’s concerns about antisemitism in Australia and Israel. The theoretical bidirectional nature of this relationship was not tested and may be a limitation of the current analysis. In addition, the second moderator relied on denominational identification as a proxy for Jewish communal ties and while intergroup comparisons revealed statistically different patterns in attitudes and behaviors vis-à-vis Jewish communal ties, future research would benefit from a moderator that is constructed from a scale that includes explicit measures of these constructs.

Rich qualitative data were gathered by the survey which has been used only sparingly in the development of the hypotheses in this paper; future research could utilize that data for other lines of inquiry. At the time of writing, the war between Israel and Hamas continues and the Australian Jewish community continues to experience heightened levels of antisemitism. Future analysis of the same population would provide an appropriate way of gauging how Australian Jews are faring and how the effects of social media, the sources of concern and sources of support continue to impact on their mental health.

Notes

In a survey conducted 4 months prior to October 7, 17% of respondents to that same question selected the highest response option, that their reaction “is so strong that it is almost the same as if my own life was in danger” (Markus 2023). While these results appear similar to those of the 2017 survey (Graham and Markus 2017), we would caution against comparisons, as the former survey was not weighted to align demographically with the Australian Census, nor was it weighted for level of Jewish engagement.

The terms positive and negative are only used in these analyses to discuss statistically significant results. Thus, if an effect is positive, it refers to a statistically significant increase in anxiety and, if an effect is negative, it refers to a statistically significant decrease in measured anxiety.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2023. National study of mental health and wellbeing 2020–2022, viewed March 8 2024. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-study-mental-health-and-wellbeing/latest-release.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2024. Prevalence and impact of mental illness. https://www.aihw.gov.au/mental-health/overview/prevalence-and-impact-of-mental-illness

Bankier-Karp, Adina L., and David J. Graham. 2024. Australian Jews in the shadow of war survey. Australian Centre for Jewish Civilisation, Monash University and JCA Sydney. https://www.monash.edu/arts/acjc/research-and-projects/current-projects/australian-Australian Jews-in-the-shadow-of-war

Bankier-Karp, Adina L., and Michelle Shain. 2021. COVID-19’s effects upon the religious group resources, psychosocial resources, and mental health of Orthodox Jews. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 61 (1): 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12770.

Bergman, Ronen, and Yoav Zeiton. 2023. The first hours of the black sabbath [Hebrew]. Ynet. https://w.ynet.co.il/yediot/7-days/time-of-darkness

Boustead, Roz, and Mal Flack. 2021. Moderated-mediation analysis of problematic social networking use: The role of anxious attachment orientation, fear of missing out and satisfaction with life. Addictive Behaviors 119: 106938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106938.

Demetriadi, Alexi and Joanna Panagopolous. 2023. Israel at war: Flares set off at Sydney Opera House amid sails tribute to Israel (11/08/2023): 1. The Australian. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/nation/world/israel-at-war-death-toll-soars-as-biden-pledges-munitions-to-israel-will-boost-forces-in-region-pentagon/live-coverage/f41dcdd0e7caf48b42441d612a08e1a2.

Demetriadi, Alexi. 2023. “Elated” Sheik Ibrahim Dadoun’s Lakemba comments slammed by political and religious leaders (11/09/2023). The Australian. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/nation/elated-sheik-ibrahim-dadouns-lakemba-comments-slammed-by-political-and-religious-leaders/news-story/380573cc0778a30a2230c6876eecb137.

Durkheim, Emile. 2005. Suicide: A study in sociology. London: Routledge.

Ferraro, Kenneth, and Lindsay Wilkinson. 2013. Age, aging, and mental health. In Handbook of the Sociology of Mental, ed. Carol Aneshensel, Jo Phelan, and Alex Bierman, 183–203. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4276-5_10.

Fredrickson, Barbara. 2002. How does religion benefit health and well-being? Are positive emotions active ingredients. Psychological Inquiry 13 (3): 209–213.

Graham, David J., and Andrew Markus. 2018. GEN17 Australian Jewish community survey: Preliminary findings. ACJC Monash University and JCA NSW. https://www.monash.edu/arts/acjc/research-and-projects/past-projects/jewish-attitudinal-surveys/gen17

Graham, David J. 2024. The Jewish population of Australia: Key findings from the 2021 Census. JCA Sydney. https://jca.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/The-Jewish-Population-of-Australia-Report_2021-Census-1.pdf

Haidt, Jonathan. 2024. The anxious generation: How the great rewiring of childhood is causing an epidemic of mental illness. New York: Penguin Press.

Hall, Jeffrey A., Michael W. Kearney, and Chong Xing. 2019. Two tests of social displacement through social media use. Information, Communication & Society 22 (10): 1396–1413. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1430162.

Halpern-Manners, Andrew, Landon Schnabel, Elaine M. Hernandez, Judy L. Silberg, and Lindon J. Eaves. 2016. The relationship between education and mental health: New evidence from a discordant twin study. Social Forces 95 (1): 107–131. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sow035.

Hayes, Andrew. 2017. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

King, Alan, Tiffany Russell, and Amy Veith. 2017. Friendship and mental health functioning. In The Psychology of Friendship, ed. Mahzad Hojjat and Anne Moyer, 249–300. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kondirolli, Fjolla, and Naveen Sunder. 2022. Mental health effects of education. Health Economics 31 (S2): 22–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.4565.

Lai, Fengxia, Lihong Wang, Jiyin Zhang, Shengnan Shan, Jing Chen, and Li. Tian. 2023. Relationship between social media use and social anxiety in college students: Mediation effect of communication capacity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20 (4): 3657.

Lin, Liu Yi, Jaime Sidani, Ariel Shensa, Ana Radovic, Elizabeth Miller, Jason Colditz, Beth Hoffman, Leila Giles, and Brian Primack. 2016. Association between social media use and depression among U.S. young adults. Depression and Anxiety 33 (4): 323–331. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22466.

Markus, Andrew. 2023. Crossroads23: Surveying Australian Jews on Israel. Plus61J Media. https://jewishindependent.yourcreative.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Crossroads23_Survey_Report_June_2023_2-1.pdf

McCracken, Tess, and Tricia Rivera. 2023. Israel-Gaza war: Antisemitism creating ‘palpable fear’ in Victorian Jewish community (10/31/2023): 2. The Australian. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/nation/israelgaza-war-antisemitism-creating-palpable-fear-in-victorian-jewish-community/news-story/10b06881ed803de8ae4fd0408f62f6d7.

Oboler, Andre, Eliyahou Roth, Jasmine Beinart, and Jessen Beinart. 2024. Online antisemitism after 7 October 2023. Online Hate Prevention Institute. https://ohpi.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Online_Antisemitism_After_October_7.pdf

Öhman, Arne. 2008. Fear and anxiety: Overlaps and dissociations. In Handbook of emotions (Third edition), ed. Michael Lewis, Jeannette Haviland-Jones, and Lisa Feldman Barrett, 709–729. New York: The Guildford Press.

Panagopoulos, Joanna, James Dowling, and Fergus Ellis. 2023. We have loved ones who died – it’s not just over there, it’s happening to us in Australia too. (10/11/2023): 2-3. The Australian. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/world/israeli-diaspora-its-not-just-over-there-its-happening-to-us-in-australia-too/news-story/039a0af6b5c535d5ef465b2c44884d56.

Pargament, Kenneth I., Gene G. Ano, and Amy Wachholtz. 2005. The religious dimension of coping. In Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality, ed. Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park, 479–495. New York: The Guilford Press.

Pew Research Center. 2019. Religion’s relationship to happiness, civic engagement and health around the world. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2019/01/31/religions-relationship-to-happiness-civic-engagement-and-health-around-the-world/

Purba, Amrit Kaur, Rachel Thomson, Paul Henery, Anna Pearce, Marion Henderson, and S. Vittal Katikireddi. 2023. Social media use and health risk behaviours in young people: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal 383: e073552-e107355. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-073552.

Rosenfield, Sarah, and Dawne Mouzon. 2013. Gender and mental health. In Handbook of the sociology of mental health, ed. Carol S. Aneshensel, Jo C. Phelan, and Alex Bierman, 277–296. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4276-5_14

Rosmarin, David, and Bethany Leidl. 2020. Spirituality, religion and anxiety disorders. In Handbook of Spirituality, Religion, and Mental Health, 2nd ed., ed. David Rosmarin and Harold G. Koenig, 41–60. London: Academic Press.

Seabrook, Elizabeth, Margaret Kern, and Nikki Rickard. 2016. Social networking sites, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review. JMIR Mental Health 3 (4): e50. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.5842.

Shensa, Ariel, Jaime Sidani, Mary Dew, César. Escobar-Viera, and Brian Primack. 2018. Social media use and depression and anxiety symptoms: A cluster analysis. American Journal of Health Behavior 42 (2): 116–128. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.42.2.11.

Shyman, J. 2023. Israeli casualties of October 7th, 2023 (11/23/2023). Zaka. https://zakaworld.org/israeli-casualties-of-october-7th-2023/.

Staples, Lauren, Blake Dear, Milena Gandy, Vincent Fogliati, Rhiannon Fogliati, Eyal Karin, Olav Nielssen, and Nickolai Titov. 2019. Psychometric properties and clinical utility of brief measures of depression, anxiety, and general distress: The PHQ-2, GAD-2, and K-6. General Hospital Psychiatry 56: 13–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.11.003.

Tillman, Gabriel, Evita March, Andrew Lavender, Taylor Braund, and Christopher Mesagno. 2023. Disordered social media use during COVID-19 predicts perceived stress and depression through indirect effects via fear of COVID-19. Behavioral Science (basel) 13 (9): 698–770. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090698.

Waldinger, Robert, and Marc Schulz. 2023. The good life: Lessons from the world’s longest scientific study of happiness. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Wittchen, Hans-Ulrich, and Jurgen Hoyer. 2001. Generalized anxiety disorder: Nature and course. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 62 (Suppl. 11): 15–19. https://www.psychiatrist.com/read-pdf/7719/.

Wright, Graham, Sasha Volodarsky, Shahar Hecht, and Leonard Saxe. 2023. In the shadow of war: Hotspots of antisemitism on US college campuses. Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies, Brandeis University. https://www.brandeis.edu/cmjs/research/antisemitism/hotspots-2023-report1.html

Wu, David. 2023.10.10. Flares set off at Sydney Opera House lit up in blue and white as pro-Palestine protesters appear to burn Israel flag. Sky News Australia. https://www.skynews.com.au/australia-news/flares-set-off-at-sydney-opera-house-lit-up-in-blue-and-white-as-propalestine-protesters-appear-to-burn-israel-flag/news-story/71561cf241bdf9a33373ec783bc41241

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. The research leading to these results received funding from the Loti and Victor Smorgon Family Foundation and the JCA Sydney.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Adina Bankier-Karp is associate editor at Contemporary Jewry. The Australian Jews in the shadow of war survey was sponsored by the Loti and Victor Smorgon Family Foundation and JCA, in partnership with Australian Jewish Funders.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 2, 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , and 9 .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bankier-Karp, A.L., Graham, D. Surrounded by Darkness, Enfolded in Light: Factors Influencing the Mental Health of Australian Jews in the October 7 Aftermath. Cont Jewry (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12397-024-09584-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12397-024-09584-4