Abstract

Across the Jewish world religious polarization is gaining momentum. At the secular end of the spectrum people are switching away from religion while at the religious pole fertility levels are high. This trend is evident among South African Jewry; data from the 2019 Jewish Community Survey of South Africa (N = 4193) show that the community is becoming polarized, and the traditional center ground is collapsing. However, unlike many other Jewish communities today, switching toward more religious subgroups than the one in which one was raised is more common in South Africa than switching away from them. This tendency is most pronounced among people born in the 1960s and 1970s. A similar trend characterizes South African non-Jews. We argue that coming of age in a period of profound political and social instability explains the increased likelihood of switching toward religion. The effect is more marked among Jews due to distinct communal characteristics and history that provided the optimal conditions for switching towards a more religious lifestyle. This paper highlights the necessity of examining internal processes that are unique to the Jewish community alongside broader developments to improve our understanding of religious polarization among Jews.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

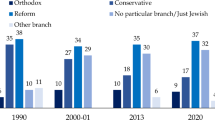

Jewish communities are becoming increasingly polarized, with the traditional center ground of Jewish life declining, be it the Conservative movement in the USA (Keysar and DellaPergola 2019), Masoratim in Israel (CBS 2002–2021), or those who identify as Traditional in the UK (Graham, Staetsky, and Boyd 2014). Rising proportions of each cohort identify with the religious subgroups at either pole of the religiosity continuum: Haredim and just Jewish/Secular (CBS 2002–2021; Pew 2013; 2020). This is in sharp contrast with trends among non-Jews in much of the western world, which exhibit a shift away from religion, but little sign of strengthening of the more religious sectors of the population (Voas and Chaves 2016).

The numerical increase at the religious end of the spectrum seen in many Jewish communities tends to be a function of high birth rates (Kaufmann 2010; Pinker 2021; Staetsky and Boyd 2015). While there are those that theorize such a trajectory among non-Jewish western populations in the future, thus far there is no sign of such developments (Stonawski et al. 2015). At the more secular end of the spectrum, on the other hand, an entirely different causal mechanism is responsible for shifting religiosity: The failure of religious transmission from parent to child and religious switching between subgroups that occurs during an individual’s lifetime drive up the numbers of the more secular subgroups within religions as well as those who are unaffiliated (Beider 2018; Keysar and DellaPergola 2019; Thiessen and Wilkins-Laflamme 2017; Voas and Chaves 2016). The result of these countervailing trends is that the historic center ground of many Jewish communities is collapsing (Rebhun 2023).

This paper examines religious polarization in the South African Jewish community, with a focus on the unique role played by religious switching. South Africa is unusual, as within the Jewish community switching to a more religious subgroup is more common than switching to a more secular one. This is explained by both local political and economic developments, as well as the particular character and history of the South African Jewish community. This case study focuses on South Africa to highlight how switching patterns there differ from those found in the rest of the Jewish world and makes comparisons between Jews and non-Jews in that country. In doing so, it reflects the inherent complexity of patterns of religious change in Jewish communities that need to be understood in both their local and broader Jewish contexts.

Religious Polarization

To understand religious switching in South Africa, we begin by examining religious polarization across the Jewish world and then move to an examination of the mechanisms driving polarization. In Israel, the USA, and many other Jewish communities there are signs of religious polarization. The subgroups at both poles of the religious spectrum, namely the Haredi or strictly Orthodox on the one hand, and the Secular or “just Jewish,” on the other, are gaining ground. By contrast, the proportion identifying with one of the centrist subgroups, such as the Conservative movement in the USA, Masoratim in Israel, and those who identify as Traditional in the UK and Australia, is in decline (CBS 2002–2021; Graham and Markus 2018; Graham et al.2014; Pew 2020). It goes without saying that the characteristics of each of these subgroups vary somewhat across Jewish communities in different locations. However, an awareness of the significance of local context does not negate the clear pattern of polarization in several countries, as the population distribution across the religious spectrum shifts away from the center over time.

The mechanisms driving the polarization process differ at either end of the religious continuum. Individual switching tends to be in the direction of secularity, mirroring the decline of religion in the west and swelling the ranks of the non-denominationally identified “just Jewish” or Secular (Lazerwitz 1995; Sands et al. 2006). On the other hand, higher fertility rates and earlier age of marriage among the more religious sectors of the community, primarily Haredim, but also the Orthodox, or Dati groups, result in greater natural growth of the more religiously committed subgroups (Keysar and DellaPergola 2019; Pinker 2021; Staetsky and Boyd 2015). The Kaufmann, Goujon, and Skirbekk thesis (2012), which posits that higher fertility among the more religious will lead to a resurgence of religion, may be true for Jews, but is not well supported in western Christian societies. However, global projections of the future size of religious groups indicate that low rates of marriage, postponement of childbearing, and low total fertility rates among the unaffiliated are likely to adversely affect the global population share of the unaffiliated. Similarly, high fertility among Muslims is the main reason that projections indicate Islam’s population share will increase rapidly, nearly reaching parity with Christianity in 2050 (Pew 2015).

The fertility differentials and subsequent difference in age distribution between the different religious subgroups among Jews are particularly striking (Rebhun 2016; Shain 2019; Waxman 2017). The fact that religious Jews have many more children than their secular coreligionists, and the concomitant overrepresentation of the more religious in the youngest age groups, appears to be the primary driving force behind religious polarization in Israel (Bystrov 2016; Okun 2017) and the UK (Kaufmann 2010). Thus, in the UK and Israel, Haredim constitute less than 5% of those in their sixties, but 13.5% of those in their twenties in the UK and 16.6% in Israel (CBS 2021; Staetsky and Boyd 2015).

Reasons for Individual Religious Switching

While demographic forces account for one side of the polarization equation, explaining the rise in the proportion of highly committed Jews, the collapse of the center is also due to the cumulative effect of individual switching away from religion. Several theoretical explanations for this type of change have been advanced, chief among them classical secularization theory (Durkheim 1964), declining religious plausibility (Berger 1967), and rising socioeconomic status (Stark and Glock 1968). More recently, the clash between theology and political values (Hout and Fischer 2002, 2014) has been suggested as a reason for people to switch out of religion altogether.

Switching toward religion, on the other hand, has often been explained in psychological terms, as a coping mechanism (Beit-Hallahmi and Nevo 1987). The appearance of the global Ba’al TeshuvaFootnote 1 movement (Aviad 1983) has been identified with a broader phenomenon of “religious seeking,” particularly among the baby boomer generation (Roof 1994). Among American Orthodox Jews, Heilman (2006) noted a shift to the right, although its significance has been debated and countertrends highlighted (Turetsky and Waxman 2011). The mechanisms and processes of individual transitions towards Orthodoxy have been explored (Davidman 1991; Bunin Benor 2012; Sands 2019), with attention paid to the South African case and especially to the impact of such switching on family ties (Sands and Roer Strier 2000). However, this kind of switching has been something of a fringe movement, numerically less significant than transitions away from stricter forms of Judaism.

Cohort-Based Religious Change

Having examined the reasons for religious change, we now turn to two competing theoretical perspectives for understanding religious change. A cohort approach focuses on the ways in which the experience of each cohort is shaped by the social norms and structures of their societies, while a period effect is caused by an event that affects all cohorts equally at a given point in time. As adolescence is the age at which identities coalesce, the experience of each cohort in the formative teenage years is crucial (Desmond et al. 2010).

Individual religious change, particularly in the direction of reduced religious commitment, is perhaps best conceptualized as part of an intergenerational decline in religious belonging, belief, and behavior (Kaufmann et al. 2012; Rebhun 2023; Tilley 2003; Voas and Chaves 2016; Voas and Doebler 2011). Parents might be attempting to transmit their religion to the next generation but are failing to do so, as the task of religious transmission becomes increasingly difficult as successive cohorts are born into societies that are becoming progressively more secular (Maliepaard and Lubbers 2013). Furthermore, the decline of traditional family structures in which all family members belong to the same faith (Lawton and Bures 2001; Wilkinson 2018) renders successful religious transmission less likely. Each successive cohort is less likely to experience religious socialization from the immediate or broader family (Copen and Silverstein 2008; Voas and Storm 2012). As society itself becomes less religious, the chances of religious socialization occurring in communities (Lim and de Graaf 2021; Petts 2014; Voas and Storm 2012), schools (Strhan and Shillitoe 2019), and peer groups (Adams et al. 2020; Cheadle and Schwadel 2012) decline concomitantly.

Period Effects

Period effects refer to the impact of major geopolitical and social events on the entire population. Religious switching is rarely subject to period effects, but the counterculture of the 1960s and the fall of communism did influence societal switching trends, with switching away from religion a result of the former, while the latter had the opposite effect (Schwadel 2010; Tilley 2003). It seems that in the immediate aftermath of the fall of communism in Eastern Europe, religion underwent a revival, with large numbers of people who had no previous affiliation beginning to identify as Christians (Northmore-Ball and Evans 2016). Although period effects are less common than cohort effects in terms of religious change, in the South African context, the tumultuous events of the late apartheid era may have had a significant impact on patterns of religiosity across all cohorts.

Religious Switching and Sociodemographic Characteristics

Individual religious change is affected not only by parental socialization and period effects, but also by sociodemographic factors. The gender gap in religiosity suggests that women would be more likely to switch toward religion and men more likely to move away from it (Suh and Russell 2015), although it may be that Jews do not conform to Christian gender patterns (Schnabel et al. 2018). Adolescent experiences shape religious change decisions (Desmond et al. 2010). Therefore, we hypothesize that the instability of the years 1975–1995 that represent the height of political instability as the struggles over apartheid reached their peak will most affect the cohorts born in the 1960s and 1970s who were adolescents during that tumultuous period. Ethnicity has been shown to be related to religious switching patterns in Israel, with Jews who trace their heritage to African and Asia more likely to switch (Beider 2018), although how this might translate to the very different ethnic composition of South African Jewry is not clear. Education was historically associated with a switch away from religion, although in recent years that relationship has been debated (Schwadel 2011). The association between immigration and religiosity among Jews (Bankier-Karp 2023) suggests that immigrants may be more likely to switch in the direction of stricter commitment, perhaps because religion may provide spiritual or even social resources that alleviate some of their difficulties.

The Religious Landscape of South African Jewry

The Jewish community of South Africa numbers approximately 52,300 (DellaPergola 2022) making it the eleventh largest in the world. The first communal organizations were founded over one hundred and fifty years ago. The initial Jewish settlers in the country were mainly of English origin, with some German Jews and a smattering of Dutch immigrants (Mazabow 2008). However, they were quickly outnumbered by immigrants from Eastern Europe, primarily Lithuania (Kaplan and Robertson 1991). They were later joined by a small number of Central Europeans fleeing Nazi persecution in the 1930s (Shimoni 2003). Until the first decade of the twentieth century, communal organizations were mainly led by English Jews. Although this changed over the next decades, the English influence was felt especially in religious institutions. This meant that unlike the informalities of Lithuanian Jewish customs, most synagogues in Johannesburg were English in style, with clergy dressed in canonicals, the lay leadership in top hats, and the cantor and choir in very formal dress (Simon 1996). The rabbis at that time hailed mainly from England or Western Europe and tended to broadcast a very universal inclusive message. As far as the community was concerned, they were largely uneducated in religious matters and tended not to adhere to strict religious observance.

Jews were always a small minority in South Africa, peaking at approximately one hundred and twenty thousand in 1970 (Shimoni 2003), declining by about a third in thirty years (Bruk 2006). As mentioned above, the community is now estimated to be 52,300 (DellaPergola 2022), less than half what it was 50 years earlier. Although they are only a small fraction of the general population, Jews represent a larger proportion of the white population, especially in the big cities. For example, one-tenth of Johannesburg’s white residents at the turn of the twentieth century (soon after the city was established) was estimated to be Jewish (Rubin 2004). The South African political environment had from its beginning promoted segregation and separate development that not only divided the races but also the religious communities. Most Jews, irrespective of how much they observed, nurtured their Jewish identity by being affiliated with Jewish congregations (DellaPergola and Dubb 1988). This meant that certain public practices, such as attending synagogue on Friday night, lighting Sabbath candles, fasting on Yom Kippur, and attending a Passover Seder, were widely observed. Thus, the majority of South African Jews identified as Traditional, observed some practices, but did not feel bound by many other strictures of Jewish law, and may be termed “non-observant Orthodox” (Hellig 1987; Gilbert and Posel 2021), similar in many ways to Masorati Jews in Israel (Yadgar 2010).

A small contingent was historically affiliated with the Reform movement (Manoim, 2019) and a smaller number identified as secular or atheists. Over the decades the proportion of Orthodox and strictly Orthodox Jews rose very slightly, with each decade seeing a higher rate of change than the previous one. This trend was accelerated sharply in the 1970s when two overseas movements successfully formed communities where most congregants were highly observant. The earlier movement was the Kollel Yad Shaul, established in 1970. It was quickly followed by Chabad in 1972 and by other independent congregations. During the 1980s Ohr Somayach was established in South Africa. It had an even greater impact than either Chabad or Kollel Yad Shaul and was responsible for large sections of the student population adopting a much stricter Orthodox lifestyle in the 1980s and 1990s. This meant that many of those who had previously identified as Traditional became Orthodox or strictly Orthodox.

By the mid-1990s this trend had peaked, but the outreach until then was sufficiently powerful to create a fairly large contingent of observant Jews, who would represent a significant faction of the overall Jewish community. It is likely that their high birthrate when compared with their secular counterparts has been responsible for their increasing proportion among the broader community. Thus, in the last few decades leading to the 2020s, Johannesburg has witnessed a proliferation of strictly Orthodox schools and a mushrooming of informal small synagogues or shtetlach, with the concomitant fall in membership of the large synagogues (Saks 2022). This is despite high rates of emigration from South Africa to Australia, Israel, the USA, and the UK and a high proportion of the local population considering emigrating in the future (Bruk 2006; Kosmin, Goldberg, Shain, and Bruk 1999).

Methodology

Data

The data for this analysis derive from the Jewish Community Survey of South Africa, an online survey of South African Jews carried out in 2019.Footnote 2 Although the survey is not a nationally representative sample of the entire South African Jewish population, nevertheless it is representative of all Jews who are likely to ever engage with the Jewish community. The dataset is comprised of 4193 adult men and women living in South Africa who consider themselves to be “Jewish in any way at all.”

Variables

Our dependent variable is a measure of switching between the religious subgroups of the South African Jewish community. It indicates whether, and what type, of religious switch occurred. In South Africa, as in Israel, the UK, and many other Jewish communities, the primary divisions within the Jewish community do not run on entirely denominational lines as they do in the USA. However, the religious subgroups that are recognizable and understood within the community are the ones employed in this analysis. These subgroups include, but are not limited to, denominational groups.

The dependent variable is created on the basis of two separate survey questions that relate to the subgroup identity of the home in which the respondent was raised, “How would you describe the religious/Jewish identification of the home in which you grew up?” and the respondent’s current subgroup identity, “And how would you describe your current religious/Jewish identification?” There are eight possible responses to these questions: (1) strictly Orthodox/Haredi/Chasidic, (2) Orthodox, (3) Traditional, (4) Progressive/Reform, (5) Secular/Cultural, (6) mixed religion, (7) not Jewish, and (8) other.

The dependent variable distinguishes between those who switched to a more religious subgroup, those who currently identify with the same subgroup as the home in which they grew up (the reference category), and those who switched away from religious tradition. The small number of respondents who identified with “other,” either in childhood or currently, are excluded from the analysis, reducing the sample size to 3687 respondents. While we recognize that denominational divisions rest on questions of ideology, not just religiosity, there is sufficient evidence (DellaPergola and Staetsky 2022; Graham and Markus 2018; Pew 2015, 2020) to suggest that these groups can be placed on a spectrum of religiosity. The data analyzed here indicate that South African Jews conform to the same pattern.

Independent Variables

An indicator of childhood religiosity accounts for within religious subgroup differences in religiosity as a child. Religious socialization shapes switching preferences and religiosity in adulthood (Babchuk and Whitt 1990; Wilkins-Laflamme 2020). The survey includes a number of questions that probe the religious character of the home in which the respondent was raised, but for some of these indicators there was little variation in responses, for example, the vast majority of South African Jews always attended Passover Seder in their youth. The inclusion of such an indicator adds little to our understanding of religious dynamics. Therefore, we use the question, “How often, if at all, did you have a Friday night (Shabbat) meal with your family/friends during your upbringing?”

Sociodemographic variables include gender, (synthetic) cohort, ethnicity, education, and nativity status. Female is the reference category for gender. Cohort distinguishes between those born prior to 1950 (the reference category), 1950–1959, 1960–1969, 1970–1979, 1980–1989, and 1990–2001. Ethnicity distinguishes between Ashkenazi and Sephardi, mixed, or other with the former set as the reference group. Education is coded as a dummy variable, with high school education or less being the reference category. Nativity status is coded 1 for those born outside South Africa; the native-born are the reference group.

This analysis focuses on the importance of birth cohorts in determining religious trajectories. However, life-cycle effects such as family formation also play a role (Bengtson et al. 2018; Blekesaune and Skirbekk 2022). We, therefore, include marital status in model 2 to control for these effects. As the date of religious switch and marriage are both unknown, it is impossible to explore causal relationships; the inclusion of these variables is designed to ensure that cohort effects are not reflective of life-cycle factors. Marital status distinguishes between those who have never been married (the reference group), those who are married, and the separated, divorced, and widowed combined.

Methods

The initial analysis demonstrates the scale and direction of religious switching among South African Jews. To understand the determinants of religious switching, we run multivariate regressions. As the dependent variable has three possible outcomes (switching to a more religious subgroup, remaining in the subgroup in which one was raised, and switching to a less religious subgroup), we employ multinomial regression technique comparing the determinants of switching to a more or less religious subgroup relative to having stayed in the same group. To ensure that the differences found are not only relative to the reference category of religious stayers, separate regressions not shown here tested the determinants of switching to a more religious subgroup or staying in the same subgroup, relative to having switched to a less religious subgroup. This allows to compare between those who switched in different directions, as well as between switchers and stayers. As year of birth was a focus of this analysis, we used Weight_GeogSexAge weights throughout, per the advice of those who administered the survey. Means of the independent variables included in the analysis are presented in the Appendix.

Results

Polarization

There is clear evidence of religious polarization among South African Jews. Almost half of the respondents indicated that they were raised in a Traditional home, yet only around a third currently identify as such (Fig. 1). The net effect of religious switching is the almost doubling of the two groups at the poles of the spectrum namely of those who identify only as Jewish, namely the strictly Orthodox/Haredi/Chasidic and Secular/Cultural groups. The two more centrist groups—Orthodox and Progressive/Liberal—have also grown, although not to the same extent. The Traditional subgroup, once the mainstay of the community, remains the largest group, albeit only by a small margin. If current trends continue, it will be eclipsed by the Orthodox.

Religious Switching Patterns

A more detailed analysis of religious switching among South African Jews (Fig. 2) reveals that of those raised Traditional, a little under half currently identify as such, around a quarter switched to Orthodox, and an eighth are now Secular/Cultural Jews. The numbers switching into the Traditional group, primarily from the Orthodox, do not offset these losses. For those raised Orthodox, the retention rate stands at approximately three-fifths, with just under a fifth switching to Traditional.

In common with other Jewish communities, the retention rate among the strictly Orthodox is the highest, at a little under three-quarters. Compared with retention rate for this group in Israel, which is estimated to be well over ninety percent (Pew 2015), this is a fairly low number, indicative of the high rate of religious volatility in the South African Jewish community. A slight majority of those raised Progressive/Liberal continue to identify with these subgroups, while the retention rate of Secular/Cultural Jews is a little higher, at over three-fifths. The majority of new adherents to these groups were raised Traditional, which is unsurprising given the high proportion of respondents raised Traditional and the low retention rate of that subgroup.

South Africa’s high emigration rates could conceivably contribute to religious polarization, for example, if those who identified as Traditional were disproportionately likely to emigrate. We are unable to fully account for this possibility as South African emigres, who are now spread across several countries, are not included in the survey population. Were it feasible to locate them, it would be difficult to ascertain their religious identity prior to emigration. Furthermore, it would be almost impossible to disentangle the effect of their South African upbringing from the impact of their new environment and the migration process itself, on religious change decisions.

Notwithstanding these difficulties, the South African Jewish Community Survey does include an indicator of the attitudes of South African Jews towards emigration. Similar proportions (between 33.0% and 46.6%) of all religious subgroups considered emigrating in the last 12 months. There is no clear relationship between position on the religious spectrum and likelihood of contemplating emigration. The Orthodox are, admittedly by a small margin, the most likely to have considered such a move, followed by those who identify with Judaism and another religion, strictly Orthodox, Traditional, Progressive/Reform, and Secular/Cultural. Thus, there is no evidence to support the hypothesis that religious polarization in South Africa has been caused by differential emigration rates by religious subgroup.

Conversely, fertility differentials by religious subgroup do contribute to religious polarization. In South Africa, fertility and switching are not two countervailing trends as they are in Jewish communities elsewhere, but complementary ones, as natural growth in the Orthodox and strictly Orthodox communities is augmented by switching to these subgroups. In any case, this research focuses on religious trajectories of the individual, rather than generational differences driven by changing proportions of each religious subgroup in each subsequent generation.

Determinants of Religious Switching

The results of multinomial regressions (Table 1) indicate that birth cohort is an important determinant of the direction of religious switching. Both models confirm the hypothesis that respondents born in the 1960s and 1970s are much more likely to have switched to a more religious subgroup than those born before 1950. Previous research has demonstrated that religiosity increases with marriage and family formation, which could explain the differences in religious patterns by cohort. However, in model 2, which controls for this effect, the pattern is unchanged, indicating that the tendency of those born in the 1960s, 1970s, and to some degree the 1980s, to switch to a more religious subgroup is not simply a matter of life cycle stage and family formation. Those born in the 1990s demonstrate signs of stability in their religious subgroup identity relative to those born prior to 1950, perhaps because they are too young to have switched in great numbers. Any increase in the population share of the Orthodox and strictly Orthodox in the last 20 years is therefore not a result of religious switching and is more likely a function of higher fertility rates among these groups.

When year of birth is related to a life event, it may be a function of age, period, or birth cohort. Age effects are unlikely in this case, as controlling for marriage (in model 2) does not much alter the relationship found in model 1. Little can be read into the finding that those who are married are likely to have switched subgroup in the direction of greater religiosity as this may be a cause or effect of their switch and is included simply to control for life-cycle effects. Furthermore, while religiosity may fluctuate across the life course, the evidence suggests that the majority of religious switching tends to occur during adolescence and emerging adulthood, rather than at the age of family formation (Beider 2022; Desmond et al.2010; Vaidyanathan 2011).

Therefore, we suggest that cohort effects are strongly responsible for this pattern of religious switching. The cohorts born in the 1960s and 1970s were adolescents during the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s, a period of turmoil and instability in South Africa. These were the years of the Soweto uprising, the State of Emergency, and the fall of apartheid. Those born in the 1980s appear to have been somewhat affected, as stability did not return immediately after the end of apartheid in 1994.

Contrary to expectations, Jews born outside South Africa are much less likely than native South African Jews to have switched to a more religious subgroup, consistent with the notion that this is a uniquely South African phenomenon, a result of the political environment that shaped these particular cohorts as their adolescent experiences shaped their religious trajectories. A sense of security seems to be a precursor to switching away from religion (Norris and Inglehart 2004), whereas in times of uncertainty and violence, it may be that people are more likely to turn to religion. While these events could be considered period effects, their effect is concentrated on specific birth cohorts, rather than impacting upon the entire population and will therefore be considered a cohort effect.

The relationship between childhood religiosity and religious switching seems counterintuitive at first glance. Those who always attended Friday night dinners in childhood are more likely to have switched to a less religious subgroup, while those who were less likely to have attended Friday night dinners as children are more likely to have switched to a more religious subgroup. However, some of this may be explained by the available possibilities of religious switching. Those raised at either end of the religious spectrum are limited in their future religious mobility. For example, those raised strictly Orthodox are the most likely to have always taken part in Friday night dinners as children but could not possibly have switched to a more religious subgroup, as no such subgroup exists. Similarly, the positive association in model 2 between non-Ashkenazi ethnicity and switching away from religion is probably due to them having been raised in a more traditional environment than their Ashkenazi peers.

Marriage is very strongly correlated with switching towards religion. The inclusion of marriage in model 2 increases the explanatory power somewhat, indicating that life-cycle factors are closely related to religious change decisions. Whether marriage encourages greater religiosity or those who have switched towards religion are more likely to marry is beyond the scope of this analysis.

Discussion and Conclusions

There are clear signs of polarization in the South African Jewish community, as the Traditional center is declining and the strictly Orthodox, Orthodox, Progressive/Reform, and Secular/Humanist subgroups are all increasing in size. This is in line with trends in Jewish communities around the world. Some of the causal mechanisms are similar to those found elsewhere, such as differential fertility rates by religiosity and switching away from strict religion. However, South Africa bucks the trend found for Jews in Israel (CBS 2002–2021), the USA (Pew 2020), the UK (Graham et al. 2014), and Australia (Graham and Markus 2018) in that most religious switching is in the direction of stricter religiosity (Fig. 3). In fact, only a slight majority of South African Jews remained in the subgroup in which they were raised, with a quarter switching towards religion and just over a fifth away from it. It is likely that the true proportion moving away from religious tradition is a little higher, as those who no longer identify as Jewish in any way would not be included in the survey. However, accounting for this possibility, switching patterns among South African Jews are clearly dissimilar from those found in Jewish communities elsewhere, such as in Israel and the USA.Footnote 3 In those countries, religious retention rates are significantly higher, and switching is overwhelmingly away from stricter forms of religion.

Patterns of switching within the South African Jewish community are all the more remarkable given that the community was already centered around the Traditional subgroup. Therefore, trends in religious switching among South African Jews are not simply a function of the kind of religious revival found primarily in countries where the majority of the population are very secular (Northmore-Ball and Evans 2016). In those countries, when religious switching occurs, it is more likely to be towards religion because for most people, there is no more secular subgroup to switch to. Among South African Jews, in contrast, large scale switching away from religious tradition was certainly a possibility, but the path towards stricter religion proved more popular.

The reasons for this remarkable pattern of religious switching, we suggest, are related to both the external environment, and to the characteristics and development of the Jewish community itself. Switching towards a more religious subgroup is much more common among the cohorts born in the 1960s and 1970s who came of age during the period from the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s. This was a period of marked turmoil following the Soweto uprising of 1976 and the declaration of a State of Emergency in 1985 (Shimoni 2003; DellaPergola and Dubb 1988) that increased the likelihood of switching to a more religious subgroup. The effect began to subside when apartheid ended and multiracial elections were introduced in 1994. While outreach has continued in the post-Apartheid South Africa, the liberalizing influences appear to have had a negative effect on the voluntary embrace of a particularistic lifestyle (Lipskar 2017; Tatz 2017).

Indeed, some influential contemporary rabbinic figures drew the same conclusions. Rabbi Mendel Weinbach, the then head of Ohr Somayach in Jerusalem encouraged his emissaries to go to South Africa precisely because its instability had produced a serious mindset among the student population, which would make them far more susceptible to adopting a strictly Orthodox lifestyle than their carefree peers in the USA and the UK (Fachler 2022). Braude (1999) has suggested that the esoteric teachings of the very popular Rabbi Dr. Akiva Tatz provided a much-needed distraction from the harsh realities of the conditions that prevailed in the country.

Interestingly, although religious identity in Africa has remained remarkably stable over the past 20 years (Gez et al. 2022), in South Africa, there are signs that suggest a shift toward religion, and certainly levels of religious mobility not found in neighboring countries. However, this is in the context of a general instability in the data that makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions (Afrobarometer 2002–21). Separate analysis of data from the Pew (2009) surveys of religion in 19 sub-Saharan states indicate a similar pattern, although of lesser magnitude, for South African non-Jews born in the 1960s, among whom there was a marked tendency towards switching to religion, whereas switching away from religion is more common among later cohorts. It appears likely that political instability had a similar impact on both Jewish and non-Jewish South Africans, just as Norris and Inglehart (2004) theorized. The significance of local factors in driving switching to religion among South African Jews is underlined by the fact that no such tendency is noted among foreign-born South African Jews, who grew up in more stable environments, outside South Africa.

While the patterns of religious switching among South Africans of all religions is similar, the magnitude of the shift among Jews is much more marked. We suggest a number of structural and historical reasons for this. The South African Jewish community was highly traditional in outlook, in part due to the fact that the government controlled the media, censoring and filtering news and ideas it deemed undesirable. South African Jews were thus more sheltered from modernizing and secularizing global currents that swept through other Jewish communities and were, therefore, more receptive to the ideas of Orthodox Judaism. Their strong sense of Jewish identity was also a legacy of the organization of the population along ethnic or racial lines and the regime’s attempts to discourage mixing between such groups (Rutland 2022). The result is that South African Jews were more attracted by the particularistic Jewish messages associated with Orthodoxy and also evinced strong support for Zionism (Gilbert and Posel 2021). Young people in particular were drawn to such approaches. This also coincided with the rapid decrease by the 1970s of rabbis preaching the universalist message so common to their parents’ generation. Indeed, the South African government’s racial policies and its reputation as a pariah state deterred more liberal minded rabbis from ministering in South Africa. As a result, seekers of a more spiritual Judaism were left with no option other than that offered by adherents of strict Orthodoxy (Kaplan 1998).

Additionally, the community was and continues to be marked by a high degree of homogeneity. Over 80% of South African Jews can trace their ancestry back to rural Lithuania, and apart from a small number of immigrants who arrived in 1936 from central Europe, there has been almost no wide scale immigration from as far back as 1930, the year of the Quota Act (Shimoni 2003). Homogeneity coupled with the emphasis on ethnicity as an organizing principle of society (Gilbert and Posel 2021) led to dense social networks within the community that, in turn, facilitated the spread of new ideas and trends. Whereas in other countries, switching towards a more religious subgroup was very much a fringe activity, in South Africa switching, or at least expressing interest in increased religious practice, became more mainstream.

Furthermore, a number of charismatic rabbis, such as Avraham Hassan of the Kollel, Mendel Lipskar from Chabad, and Shmuel Moffson from Ohr Somayach played a significant role, capitalizing on the situation and making great headway in inducing more secular Jews to embrace a strict form of Orthodoxy (Kaplan 1998; Shimoni 2003). Thus, in the 1970s Kollel Yad Shaul and the Chabad movement recorded relatively rapid successes in attracting many members of the Jewish student population in Johannesburg who subsequently adopted a religious lifestyle. An even greater embrace of strict Orthodoxy, under the aegis of the international Ohr Somayach movement took place in the 1980s and 1990s.

Though we contend that the switch toward greater religion was, in line with the general trend, impacted greatly by political instability, we must add some caveats. While Johannesburg and its surroundings witnessed growth among the strictly Orthodox sector, this success was not replicated in the second largest, but much smaller Jewish community of Cape Town. Further study is necessary to establish whether this is a function of different trajectories in those two communities, or selection bias, with more religious people choosing to move to Johannesburg.

This paper is based on snapshot data from the communal survey of 2019. We cannot be certain when switching between subgroups occurred. Ideally, longitudinal data dating back several decades would be used to establish with greater certainty whether political instability did indeed influence religious switching patterns. However, given that as religious change generally occurs in the teens and early 20s (Beider 2022; Desmond et al. 2010), we can reasonably assume that experiences in adolescence are crucial in determining religious change decisions.

The unusual switching patterns found among South African Jews, wherein switching toward stricter religious subgroups is more common than switching in the direction of secularity contribute to religious polarization there. The proximate cause may have been the arrival of a number of charismatic ultra-Orthodox rabbis and the establishment of the Kollel Yad Shaul in 1970, Chabad in 1972, and Ohr Somayach in the mid- 1980s, all of which, in turn, and over the years, spurred the growth of other independent ultra-Orthodox synagogues and educational institutions. However, we argue that the conditions arising from the South African Jewish community’s traditional outlook, insularity and homogeneity, and the broader South African political and economic instability provided optimal conditions for large-scale switching toward stricter religion. This paper highlights the need to account for both internal processes that are unique to the Jewish community, alongside broader trends, to gain a full understanding of religious trends among Jews.

Notes

The term Ba’al Teshuva, although technically refers to anyone who has been sincerely repentant, is used to describe those who were raised secular but have since embraced an observant or Orthodox lifestyle.

For more information about the survey http://www.kaplancentre.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/151/2020/The_Jews_of_South_Africa_in_2019March2020.pdf.

Data on Jews in Israel are taken from the 2015 Pew Survey of Religion in Israel and data on Jews in the USA are taken from the 2020 Survey of Jewish Americans.

References

Adams, Jimi, David R. Schaefer, and Andrea Vest Ettekal. 2020. Crafting mosaics: Person-centered religious influence and selection in adolescent friendships. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 59 (1): 39–61.

Afrobarometer. 2002–2021. Survey Rounds 2–8. https://www.afrobarometer.org/.

Aviad, Janet. 1983. Return to Judaism: Jewish renewal in Israel. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Babchuk, Nicholas, and Hugh P. Whitt. 1990. R-order and religious switching. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 29 (2): 246–254.

Bankier-Karp, Adina. 2023. Tongue ties or fragments transformed: Making sense of similarities and differences between the five largest English-speaking Jewish communities. Contemporary Jewry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12397-023-09477-y.

Beider, Nadia. 2018. Patterns of switching among Israeli Jews: Trends, causes and implications. In Jewish population and identity: Concept and reality, ed. Sergio DellaPergola and Uzi Rebhun, 101–116. Cham: Springer.

Beider, Nadia. 2022. Motivations and types of religious change in contemporary America. Review of Religious Research 64 (4): 933–959.

Beit-Hallahmi, Benjamin, and Baruch Nevo. 1987. ‘Born again’ Jews in Israel: The dynamics of an identity change. International Journal of Psychology 22 (1): 75–81.

Bengtson, Vern L., R. David Hayward, Phil Zuckerman, and Merril Silverstein. 2018. Bringing up nones: Intergenerational influences and cohort trends. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 57 (2): 258–275.

Berger, Peter L. 1967. The sacred canopy: Elements of a sociological theory of religion. Garden City: Doubleday.

Blekesaune, Morten, and Vegard Skirbekk. 2022. Does forming a family increase religiosity? Longitudinal evidence from the British Household Panel Survey. European Sociological Review. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcac060.

Braude, Claudia. 1999. From the brotherhood of man to the world to come: The denial of the political in Rabbinic writing under Apartheid. In Jewries at the frontier: Accommodation, identity, conflict, ed. Sander L. Gilman and Milton Shain, 259–289. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Bruk, Shirley. 2006. The Jews of South Africa 2005 - report on a research study. Cape Town: Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies and Research.

Benor, Sarah Bunin. 2012. Becoming frum: How newcomers learn the language and culture of Orthodox Judaism. London: Rutgers University Press.

Bystrov, Evgenia. 2016. Religiosity, nationalism and fertility among Jews in Israel revisited. Acta Sociologica 59 (2): 171–186.

Central Bureau of Statistics of Israel (CBS). 2002–2021. Social Surveys.

Cheadle, Jacob E., and Philip Schwadel. 2012. The “friendship dynamics of religion,” or the “religious dynamics of friendship”? A social network analysis of adolescents who attend small schools. Social Science Research 41 (5): 1198–1212.

Copen, Casey E., and Merril Silverstein. 2008. The transmission of religious beliefs across generations: Do grandparents matter? Journal of Comparative Family Studies 39 (1): 59–71.

Durkheim, Emile. 1964. The division of labor in society. New York: The Free Pres.

Davidman, Lynn. 1991. Tradition in a rootless world: Women turn to Orthodox Judaism. Berkley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

DellaPergola, Sergio, and Allie Dubb. 1988. South African Jewry: A sociodemographic profile. American Jewish Year Book 88: 59–140.

DellaPergola, Sergio, and L. Daniel Staetsky. 2022. How do Jews live their Jewishness? Religious lifestyles and denominations of European Jews. London: Institute for Jewish Policy Research.

Desmond, Scott A., Kristopher H. Morgan, and George Kikuchi. 2010. Religious development: How (and why) does religiosity change from adolescence to young adulthood. Sociological Perspectives 53 (2): 247–270.

Fachler, David. 2022. Tradition, accommodation, revolution and counterrevolution: A history of a century of struggle for the soul of Orthodoxy in Johannesburg’s Jewish community, 1915-2015. Unpublished thesis. Cape Town: University of Cape Town

Gez, Yonatan, Nadia Beider, and Helga Dickow. 2022. African and not religious: The state of research on Sub-Saharan religious nones and new scholarly horizons. Africa Spectrum 57 (1): 50–71.

Gilbert, Shirli, and Deborah Posel. 2021. Israel, apartheid, and a South African Jewish dilemma. Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 20 (1): 1–21.

Graham, David, and Andrew Markus. 2018. Gen 17 Australian Jewish community survey: Preliminary findings. Melbourne: Australian Centre for Jewish Civilisation.

Graham, David, L. Daniel Staetsky, and Jonathan Boyd. 2014. Jews in the United Kingdom in 2013: Preliminary findings from the National Jewish Community Survey. London: Institute for Jewish Policy Research.

Heilman, Samuel. 2006. Sliding to the right: The contest for the future of American Jewish Orthodoxy. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Hellig, Jocelyn. 1987. The religious expression of South Africa Jewry. Religions in Southern Africa 8 (2): 3–17.

Hout, Michael, and Claude S. Fischer. 2002. Why more Americans have no religious preference: Politics and generations. American Sociological Review 67 (2): 165–190.

Hout, Michael, and Claude S. Fischer. 2014. Explaining why more Americans have no religious preference: Political backlash and generational succession, 1987–2012. Sociological Science 1: 423–447.

Kaplan, Dana Evan. 1998. South African Orthodoxy today: Tradition and change in a post-Apartheid multi-racial society. Tradition 33 (1): 71–89.

Kaplan, Mendel, and Marian Robertson, eds. 1991. Founders and followers: Johannesburg Jewry, 1887–1915. Johannesburg: Vlaeberg Publishers.

Kaufmann, Eric. 2010. Shall the religious inherit the Earth?: Demography and politics in the twenty-first century. London: Profile Books.

Kaufmann, Eric, Anne Goujon, and Vegard Skirbekk. 2012. The end of secularization in Europe?: A socio-demographic perspective. Sociology of Religion 73 (1): 69–91.

Keysar, Ariela, and Sergio DellaPergola. 2019. Demographic and religious dimensions of Jewish identification in the US and Israel: Millennials in generational perspective. Journal of Religion and Demography 6 (1): 149–188.

Kosmin, Barry A., Jacqueline Goldberg, Milton Shain, and Shirley Bruk. 1999. Jews of the “new South Africa” Highlights of the 1998 National Survey of South African Jews. Cape Town: Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies and Research.

Lawton, Leora E., and Regina Bures. 2001. Parental divorce and the “switching” of religious identity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 40 (1): 99–111.

Lazerwitz, Bernard. 1995. Denominational retention and switching among American Jews. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 34 (4): 499–506.

Lim, Chaeyoon, and Nan Dirk de Graaf. 2021. Religious diversity reconsidered: Local religious contexts and individual religiosity. Sociology of Religion 82 (1): 31–62.

Lipskar, Mendel. 2017. Interview with David Fachler. Johannesburg.

Maliepaard, Mieke, and Marcel Lubbers. 2013. Parental religious transmission after migration: The case of Dutch Muslims. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39 (3): 425–442.

Manoim, Irwin. 2019. Mavericks inside the tent: The progressive Jewish movement in South Africa and its impact on the wider community. Johannesburg: Juta.

Mazabow, Gerald. 2008. The quest for community: A short history of Jewish communal institutions in South Africa. Johannesburg: Houdini Publishers.

Northmore-Ball, Ksenia, and Geoffrey Evans. 2016. Secularization versus religious revival in Eastern Europe: Church institutional resilience, state repression and divergent paths. Social Science Research 57: 31–48.

Norris, Pippa, and Richard Inglehart. 2004. Sacred and secular: Religion and politics worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Okun, Barbara S. 2017. Religiosity and fertility: Jews in Israel. European Journal of Population 33 (4): 475–507.

Petts, Richard J. 2014. Family, religious attendance, and trajectories of psychological well-being among youth. Journal of Family Psychology 28 (6): 759–768.

Pew Research Center. 2009. Tolerance and tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2010/04/15/executive-summary-islam-and-christianity-in-sub-saharan-africa/.

Pew Research Center. 2013. A portrait of Jewish Americans. http://www.pewforum.org/2013/10/01/jewish-american-beliefs-attitudes-culture-survey/.

Pew Research Center. 2015. Israel's religiously divided society. http://www.pewforum.org/2016/03/08/israels-religiously-divided-society/

Pew Research Center. 2020. Jewish Americans in 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/05/11/jewish-americans-in-2020/.

Pinker, Edieal J. 2021. Projecting religious demographics: The case of Jews in the United States. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 60 (2): 229–251.

Rebhun, Uzi. 2016. Jews and the American religious landscape. New York: Columbia University Press.

Rebhun, Uzi. 2023. Jewish diversity in Israel. European Judaism (forthcoming).

Roof, Wade Clarke. 1994. A generation of seekers: The spiritual journeys of the baby boom generation. San Francisco: Harper Collins.

Rubin, Margot. 2004. The Jewish community of Johannesburg, 1886–1939: Landscapes of reality and imagination. Master’s Thesis, University of Pretoria.

Rutland, Suzanne. 2022. Creating transformation: South African Jews in Australia. Religions 13 (12): 1192.

Saks, David. 2022. “From Treife Medina to Bastion of Orthodoxy – the religious transformation of Johannesburg Jewry, 1915–2015.” Jewish Affairs 77(4) https://www.jewishaffairs.co.za/from-treife-medina-to-bastion-of-orthodoxy-the-religious-transformation-of-johannesburg-jewry-1915-2015/.

Sands, Roberta G. 2019. The spiritual transformation of Jews who become Orthodox. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Sands, Roberta G., Steven C. Marcus, and Rivka A. Danzig. 2006. The direction of denominational switching in Judaism. Contemporary Jewry 45 (3): 437–447.

Sands, Roberta G., and Dorit Roer-Strier. 2000. Ba’alot Teshuva daughters and their mothers: A view from South Africa. Contemporary Jewry 21 (1): 55–77.

Schnabel, Landon, Conrad Hackett, and David McClendon. 2018. Where men appear more religious than women: Turning a gender lens on Israel. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 57 (1): 80–94.

Schwadel, Philip. 2010. Jewish teenagers’ syncretism. Review of Religious Research 51 (3): 324–332.

Schwadel, Philip. 2011. The effects of education on American’s religious practices, beliefs, and affiliations. Review of Religious Research 53 (2): 161–182.

Shain, Michelle. 2019. Understanding the demographic challenge: Education, orthodoxy, and the fertility of American Jews. Contemporary Jewry 39 (2): 273–292.

Shimoni, Gideon. 2003. Community and conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa. Boston: Brandeis University Press.

Simon, John. A Study of the Nature and Development of Orthodox Judaism in South Africa c.1935”. Masters’ Thesis, University of Cape Town, 1996.

Staetsky, L. Daniel., and Jonathan Boyd. 2015. Strictly Orthodox rising: What the demography of British Jews tells us about the future of the community. London: Institute for Jewish Policy Research.

Stark, Rodney, and Charles Y. Glock. 1968. American piety: The nature of religious commitment. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Stonawski, Marcin, Vegard Skirbekk, Eric Kaufmann, and Anne Goujon. 2015. The end of secularisation through demography? Projections of Spanish religiosity. Journal of Contemporary Religion 30 (1): 1–21.

Strhan, Anna, and Rachael Shillitoe. 2019. The stickiness of non-religion? Intergenerational transmission and the formation of non-religious identities in childhood. Sociology 53 (6): 1094–1110.

Suh, Daniel, and Raymond Russell. 2015. Non-affiliation, non-denominationalism, religious switching, and denominational switching: Longitudinal analysis of the effects on religiosity. Review of Religious Research 57 (1): 25–41.

Tatz Akiva. 2017. Interview with David Fachler. London

Tilley, James R. 2003. Secularisation and aging in Britain: Does family formation cause greater religiosity? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42 (2): 269–278.

Thiessen, J., and S. Wilkins-Laflamme. 2017. Becoming a religious none: Irreligious socialization and disaffiliation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56 (1): 64–82.

Turetsky, Y., and Chaim I. Waxman. 2011. Sliding to the left? Contemporary American Modern Orthodoxy. Modern Judaism 31 (2): 119–141.

Vaidyanathan, Branson. 2011. Religious resources or differential decline? Early religious socialization and declining attendance in emerging adulthood. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50 (2): 366–387.

Voas, David, and Mark Chaves. 2016. Is the United State a counterexample to the secularization thesis? American Journal of Sociology 121 (5): 1517–1556.

Voas, David, and Stefanie Doebler. 2011. Secularization in Europe: Religious change between and within birth cohorts. Religion and Society in Central and Eastern Europe 4 (1): 39–62.

Voas, David, and Ingrid Storm. 2012. The intergenerational transmission of churchgoing in England and Australia. Review of Religious Research 53: 377–395.

Waxman, Chaim I. 2017. Social change and Halakhic evolution in American Orthodoxy. Liverpool: Littman.

Wilkins-Laflamme, Sarah. 2020. Like parent, like millennial: Inherited and switched (non)religion among young adults in the U.S. and Canada. Journal of Religion and Demography 7 (1): 123–149.

Wilkinson, Renae. 2018. Losing or choosing faith: Mother loss and religious change. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 57 (4): 758–778.

Yadgar, Yaacov. 2010. Maintaining ambivalence: Religious practice and Jewish identity among Israeli traditionists – a post-secular perspective. Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 9 (3): 397–419.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff at the Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Cape Town for sharing the data with us. We are grateful to Uzi Rebhun and Margot Rubin for their helpful comments. This work was supported by the Mandel Scholion Research Center and the Rothschild Foundation Hanadiv Europe.

Funding

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have not disclosed any competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix

Descriptive statistics of variables included in the analysis

Variable | Percentage (N) |

|---|---|

Cohort | |

1990–2001 | 11.3% (415) |

1980–1989 | 12.5% (462) |

1970–1979 | 19.3% (710) |

1960–1969 | 18.3% (674) |

1950–1959 | 19.3% (710) |

Pre-1950 | 19.4% (716) |

Gender | |

Female | 51.8% (1912) |

Male | 48.2% (1776) |

Nativity status | |

Foreign born | 10.7% (395) |

Native born | 89.3% (3293) |

Ethnicity | |

Ashkenazi | 89.9% (3315) |

Non-Ashkenazi | 10.1% (372) |

Education | |

University | 63.3% (2332) |

High school matriculation or less | 36.8% (1356) |

Friday night meal as child | |

Always | 61.4% (2264) |

Usually | 19.1% (706) |

Sometimes | 11.8% (434) |

Never | 7.7% (283) |

Marital status | |

Married | 67.7% (2497) |

Formerly married | 15.2% (560) |

Never married | 17.1% (630) |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Beider, N., Fachler, D. Bucking the Trend: South African Jewry and Their Turn Toward Religion. Cont Jewry 43, 661–682 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12397-023-09501-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12397-023-09501-1