Abstract

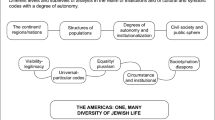

Latin American Jews constitute an increasingly large presence in the United States, posing both new opportunities and challenges for American Jewish communal life. Not only do Latin American Jews represent a significant socio-demographic group, but their incorporation into the American Jewish community increases diversity. At the same time, their inclusion tests conventional boundaries and mutual perceptions of being similar and different. Through a broad assessment of globalization, diasporas, and transnationalism, this article sheds light on diverse models of integration by Latin American Jews into the American milieu while maintaining their socio-cultural distinctiveness. Multiple ways of belonging to American Jewish institutions and organizations imply boundary maintenance and continuity—as Jews, as Latin American Jews, as Latin Americans, as Americans—while mutual influence and the transfer of original models into more or less autonomous spaces allow the display of being Latin American through their Jewishness and their Jewishness via Latin American communal patterns. Education, communal and religious life are paramount fields to explore the mosaic of experiences by Latin American Jews in the United States. Permanence amid a mobile context characterizes the presence of Latin American Jews in US cities. Miami-Dade county in Southern Florida and San Diego in Southern California serve as the focus of analysis, while comparisons are drawn with the Northeast and Middle West.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It includes diverse combinations between telecommunications, digital computers, audiovisual media, satellites, transportation technologies, as well as those brought by global corporations and supranational agencies that standardize economic, social, and cultural policy criteria.

Estimates vary between 227,500 based on the core population definition and 303,000 using the enlarged population definition.

According to the Pew Forum (2010) there are 42.8 million migrants, including unauthorized immigrants and people born in the US territories. While the United States has taken in more immigrants than any other country, the share of the US population that is foreign-born (13 %) is about average for Western industrial democracies (Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion and Public Life 2010).

This figure contrasts with smaller migrant populations: 11,283,574 from Asia; 4,817,437 from Europe; and 1,606,914 from Africa. Source: US Census Bureau, 2010 American Community Survey.

It is estimated that a similar amount migrated to Israel (115,000/150,000 core-enlarged definition) and 12,500/20,000 to other places.

In 2007, 229 Mexicans, 180 Brazilians, 141 Argentines, and 121 Colombians obtained their PhD in the United States; in 2003, naturalized individuals or non-residents constituted 19 % of those who had graduated with a PhD or were engineers employed in the United States.

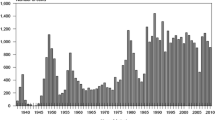

If these crises largely explain the migration of Latin American Jews, serious political turmoil, violence, and economic changes operate selectively. Thus, how migration streams change sheds light on moments of migration transition. Sharp Jewish population decreases since the mid-1980s in Central American countries are evident cases of relatively significant outflows. However, in the case of Guatemala, more than half of its population decided to stay in their homeland. Neighboring Costa Rica increased its Jewish population by two-thirds since 1967, while Panama became a relocation country for small groups of Jews fleeing from other Central American countries. The population of Jews from Venezuela shows both the increase of its population since the 1960s and the remaining of the majority of the Jewish community in the country. Argentina, which experienced sharp political and economic crises, still hosts the largest Jewish population in the continent (cf. Bokser Liwerant et al. 2010).

Latin America and the Caribbean showed the highest levels of relative growth of qualified migrants to OECD countries, while the latter’s migrant qualified population increased 111 %, from 12.3 to 25.9 million.

These flows are mainly associated to the logic of labor markets and fluid migration chains linking sending-receiving cities/countries amid an asymmetrical regionalization that connect peripheral regions of world economy to core regions of capital accumulation and development.

According to NJPS (2001), 35.9 % of Latin American Jews in the United States have an MA degree and above, 26.8 % have a BA, 20.5 % have some college education, and 16.8 % have high school or less. (Data provided to the author by Sergio DellaPergola and Uzi Rebhun). The profile of this group contrasts with lower levels of educational attainment for the majority of the foreign born from Latin America, although there is also a highly qualified stratum among Latin American non-Jewish migrants (cf. US Census Bureau, 2008–2010 American Community Service).

Looked at individually, the numbers in Miami (113,300) and Broward (185,800) are smaller than those of other cities in the country.

Private estimates point to 40,000 Latin American Jews in the state of Florida. According to the US Census, 1,097,524 Hispanic adults lived in Miami as of 2003, and 0.9 % (about 9,000) of Hispanic adults in Miami were Jewish at the time (Sheskin 2004).

Other Latin Americans also have a presence in this city but with far lower percentages (cf. http://www.census.gov/popfinder/).

According to data provided by the Pew Hispanic Center (2009), 48,348,000 Hispanics live in the United States. Of this total, 31,674,000 are Mexican (based on self-described family ancestry or place of birth). From the approximately 11.5 undocumented migrants in the United States, 6.5 million are Mexican, representing 57 % of the total (Lowell et al. 2009).

It points to inequalities and marginality that lie behind the new migratory movements, as well as the avenues by which transnational and trans-local experiences become ways to empowerment (Kennedy and Roudometof 2002).

The majority of Hispanic Jews born in South American countries, including Colombia, Venezuela, and Argentina live in North Dade (10 %), in contrast to Hispanic Jews born in Cuba who are more concentrated in the Beaches (7.1 % compared to 3.9 % in South Dade and 1.5 % in North Dade). In North Dade, other countries of origin include: Poland, Germany, Romania, Canada, Israel and Russia.

In percentage terms, San Diego (32 %) has a larger Hispanic/Latino population than Broward, Chicago (28.9 %), and NYC (28.6 %) while this population is far larger in Los Angeles (48.5 %).

Since the second half of the 20th century when some individuals and their families moved to the Northern border city of Tijuana where a new Jewish community consolidated.

In multi-ethnic societies such as Argentina and Uruguay where immigration changed the profile of the population, minorities faced a de facto tolerance that counterbalanced the primordial, territorial, and religiously homogeneous profile that the State aspired to achieve. In countries such as Mexico, Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia, where immigration did not change the original ethnic profile, the weight of ethnic differences radicalized the aspirations and national narratives of a unified nation (Avni 1998; Eisenstadt 1998).

Latin American citizens were the first ones in the modern West to have failed in their attempt to reconcile social equality with cultural differences, thereby contributing the socio-ethnically fissured nature of public life in the continent (Forment 2003). In turn, many values and institutional arrangements were cultural hybrids.

In Mexico, the Haredi schools, serving 26 % of the student population, show the highest population growth: 55 % in the last eight years. The Ashkenazi schools show the greatest percentage of decrease (28 %) and the Maguen David schools (Aleppo community schools) the highest growth rate, with 46 % of the total student population. Of this group, 40 % attend Haredi schools. Also in Argentina, the highest population growth is registered among the religious schools and in Sao Paulo, five religious schools were founded in the last years while there is a growing incorporation of Orthodox teachers into secular schools (Topel 2005; Vaad Hajinuj 2005).

It is estimated that there were 60,000 students in Jewish day schools in 1962 while by 1982–83 the student population had increased to 104,000 (10 % of the Jewish school-age population), and in 2000, it reached approximately 200,000; that is, nearly one-quarter of all Jewish school-age children attended day school. Recent studies show that today’s total enrollment nationwide is 242,000.

In 1998, the numbers were 20 % non-Orthodox, 26 % Modern Orthodox and 47 % Haredi. The growth in ultra-Orthodox or Haredi school enrollment, including both Hasidic and non-Hasidic schools, reflects high birthrates and contrasts with Modern Orthodox schools, which are essentially holding their own. At the same time, there has been a severe drop (35 %) in Solomon Schechter (Conservative movement) school enrollment. In 1998, the first year AVI CHAI foundation examined student enrollments, the Schechter attendance totaled 17,563 students in 63 schools nationwide. This year, their school enrollment is just 11,338 students in 43 schools (cf. Goldberg 2011).

Interviews with Sergio Jinich and Leslie Fastlich, July 2012, San Diego; Wizo in San Diego is headed by a Mexican woman.

In Miami, a Peruvian Jew was president of the Federation and former community leaders of Venezuela are today active members of it. Interviews with Sabi Behar, David Bassan and Paul Harriton, October, 2011, Miami.

Interview with Janche Galicot, August 2012, San Diego.

One example is Judíos Latinos, based in NYC, which was created by two young Mexican and Uruguayan Jews in an attempt to “renew the Latino Jewish community.” Their main instruments are Facebook and Twitter (Sobel n.d.).

Families as archetypes of an expanded transnational Jewish space: a person who lives in San Diego, is Honorary Consul of Israel in Tijuana and holds intense links with Mexico (Goldstein); or a diplomat representing Ecuador in Europe (Klein), whose family lives in Israel and England, developing intense transnational economic and professional activities; a family of El Salvador (Freund) participating in the American Jewish world in Miami, educated in Israeli universities and actively supporting the local community.

In 2001, Rabbi Felicia Sol (first woman rabbi) joined the congregation. See http://www.seminariorabinico.org.ar/nuevoSite/website/contenido.asp?sys=1&id=50 (last updated November 2010).

During the late 1970s, the emigration to San Diego of Rabbi Aharon Kopikis (born in Argentina and trained in the Conservative movement) had meaningful consequences given that he was a respected representative of the Bet El community in Mexico City who supported and legitimized the “migration era.” His presence became a sign of permanence in a new place where a few Mexican families shared the synagogue services with South Africans and some Americans.

Such rabbis include: Conservative rabbis Mario Rojzman (Beth Torah), Marcelo Bater (Temple Beth Israel) and Hector Epelbaum (Beth David); Orthodox rabbis Shea Rubinstein (The Shul at Barl Harbour) (Chabad), Shloime Halsband (California Club Chabad), Yossi Srugo (Aventura Chabad); Reform rabbi Arturo Kalfus (Beth Am). Sources: Interview with Juan Dierce. October 28th, 2011, Miami, and “Find a Rabbi.” Greater Miami Jewish Federation. http://jewishmiami.org/resources/find_rabbi/.

In Mexico, ethnic origins conditioned the evolutionary process of communal organizations. Its inner composition also shows radical changes. Sephardic communities, which include Sephardic and Syrian Jews from Aleppo (Halab) and Damascus (Shamis), reach today 73 % of the total Jewish population, while the Ashkenazi community constitutes only 27 %, compared to 65 % during the 1960s.

While in Mexico the presence of Chabad is marginal at best, there are more than fifty synagogues, study houses, kollelim and yeshivot, more than thirty of which were established in the last twenty-five years. Fourteen of the twenty four existing kollelim belong to the Syrian halabi community. In Brazil—where liberal Judaism, secularity, and the syncretism of the society had a strong influence—fifteen Orthodox synagogues, three yeshivot, two kollelim, and five religious schools were established in the last fifteen years (Topel 2005).

In the case of Israelis, joining Chabad in Miami, New York, and Los Angeles may be a way of belonging to a more familiar home setting, in part because the Conservative and Reform movements are still small in Israel (Gold and Phillips 1996). In Miami, Chabad also has a Venezuelan “nucleus.”

According to Faith on the Move (figures as of 2010), Christians comprise nearly half—an estimated 106 million, or 49 %—of the world’s international migrants. Muslims make up the second-largest group – almost 60 million, or 27 %. The remaining share is a mix of Hindus (11 million or 5 %), Buddhists (7 million or 3 %), Jews (more than 3.6 million or 2 %), adherents of other faiths (9 million or 4 %) and the religiously unaffiliated (19 million or 9 %) (Pew Forum 2012).

According to a recent study by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life (2012), Jews are the most mobile if compared to other religious minorities. Even given the limitations of religious allegiance as an exclusive indicator, it is worth considering that about one-quarter of Jews alive today (25 %) have left the country in which they were born and live somewhere else. By contrast, just 5 % of Christians, 4 % of Muslims, and 3 % of the global average have migrated.

In Argentina, Mr. Ellstein is the main sponsor of these initiatives and is also a well-known supporter of Chabad.

Interviews with Paul Harriton, October, 2011, Miami, and Fanny Herman, April, 2012, Chicago.

Of the Jewish adults who consider themselves to be Hispanic, the majority (29 %) come from Cuba; 18 %, from Argentina; 16 %, from Colombia; and 15 %, from Venezuela. Other countries from Latin America and the Caribbean with smaller percentages include Mexico (4 %), Uruguay (2.2 %), Peru (1.4 %), Brazil (1.3 %), Dominican Republic (0.7 %), Guatemala: (0.7 %), Chile (0.5 %), Ecuador (0.3 %), Jamaica (0.3 %), Nicaragua (0.3 %), Panama (0.3 %) and Bolivia (0.2 %) (Sheskin 2004).

References

Avni, Haim. 1988. Jews in Latin America: The contemporary Jewish dimension. In Judaica Latinoamericana, vol. I. Jerusalem: Magnes Press.

Bejarano, Margalit. 1997. From Havana to Miami, The Cuban Jewish community. In Judaica Latinoamericana. Estudios Histórico-Sociales III, 113–130. Jerusalem: AMILAT.

Biale, David, Michael Galchinsky, and Susan Heschel. 1998. American Jews and multiculturalism. Insider/outsider. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

Bokser Liwerant, Judit. 2002. Globalization and collective identities. Social Compass 49(2): 253–271.

Bokser Liwerant, Judit. 2008. Globalization and Latin American Jewish identities: The Mexican case in comparative perspective. In Jewish identities in an era of globalization and multiculturalism, eds. Judit Bokser Liwerant, Eliezer Ben-Rafael, and Yossi Gorny, 81–105. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Bokser Liwerant, Judit. 2006. Globalización, diversidad y pluralismo (Globalization, diversity and pluralism). In Diversidad y Multiculturalismo-Perspectivas y Desafíos (Diversity and Multiculturalism – Perspectives and Challenges), coord. M. Daniel Gutiérrez, 79–102. México: UNAM.

Bokser Liwerant, Judit. 2007. Jewish life in Latin America: A challenging experience. Journal of the Rabbinical Assembly.

Bokser Liwerant, Judit. 2009. Latin American Jews. A transnational diaspora. In Transnationalism, eds. Eliezer Ben-Rafael, Yitzhak Sternberg, Judit Bokser Liwerant, and Yossi Gorny, 81–105. Leiden–Boston: Brill Editorial House.

Bokser Liwerant, Judit, Sergio DellaPergola, and Leonardo Senkman. 2010. Latin American Jews in a transnational world: Redefining experiences and identities in four continents. Research Project, Jerusalem: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. The forms of capital. In Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education, ed. J.G. Richardson, 241–258. New York: Greenwood Press.

Brubaker, Roger. 2005. The “diaspora” diaspora. Ethnic and Racial Studies 28(1): 1–19.

Castles, Stephen, and Davidson Alastair. 2000. Citizenship and migration: Globalization and the politics of belonging. New York: Routledge.

Chiswick, Barry R., and Paul W. Miller. 1998. English language fluency among immigrants in the United States. Research in Labor and Economics 17: 151–200.

Clifford, James. 1994. Diasporas. Cultural Anthropology 9(3): 302–338.

Cohen, Robin. 1997. Global diasporas: An introduction. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Coleman, James S. 1988. Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology 94S: S95–S120.

DellaPergola, Sergio. 1998. The global context of migration to Israel. In Immigration to Israel: Sociological perspectives, Studies of Israeli Society, vol. 8, eds. Elazar Leshem, and Judit T. Shuval, 51–92. New Brunswick-London: Transaction Publishers.

DellaPergola, Sergio. 2008. Autonomy and dependency: Latin American Jewry in global perspective. In Identities in an era of globalization and multiculturalism: Latin America in the Jewish World, eds. Judit Bokser Liwerant, Eliezer Ben-Rafael, Yossi Gorny, and Raanan Rein, 47–80. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

DellaPergola, Sergio. 2009. International migration of Jews. In Transnationalism: Diasporas and the advent of a new (dis)order, eds. Eliezer Ben-Rafael, and Yitzhak Sternberg, Yosef Gorni, and Judit Bokser Liwerant, 213–236. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

DellaPergola, Sergio. 2011. Jewish population policies: Demographic trends and options in Israel and in the diaspora. Jerusalem: The Jewish People Policy Institute.

Eisenstadt, S.N. 1995. The constitution of collective identity. Some comparative and analytical indications. In A research programme; preliminary draft. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Eisenstadt, S.N. 1998. The construction of collective identities in Latin America: Beyond the European nation state model. In Constructing collective identities and shaping public spheres, eds. Luis Roniger, and Mario Sznajder. Brighton, Portland: Sussex Academic Press.

Eisenstadt, S.N. 2010. The new religious constellation in the framework of contemporary globalization and civilizational transformation. In World Religions and Multiculturalism, eds. Eliezer Ben Rafael, and Yitzhak Sternberg, 21-40. Boston and Leiden: Brill.

Elazar, Daniel J. 1989. People and polity: The organizational dynamics of world Jewry. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Faist, Thomas. 2010. Transnationalization and development. In Migration, development and transnationalization. A critical stance, eds. Nina Glick Schiller, and Thomas Faist. New York: Berghahn Books.

Fischer, Shlomo, and Suzanne Last Stone. 2012. Jewish Identity and Identification: New patterns, meanings and networks. Jerusalem: Jewish People Policy Institute.

Forment, Carlos. 2003. Democracy in Latin America, 1760–1900. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Glick Schiller, Nina, Linda Basch, and Christina Blanc-Szanton. 1995. From immigrant to transmigrant: Theorizing transnational migration. Anthropological Quarterly 68(1): 43–68.

Glick Schiller, Nina, and Ayse Çaglar. 2011. Locating migration. Rescaling cities and migrants. Ithaca: Cornell University.

Gold, Steven J., and Bruce A. Phillips, 1996. Israelis in the United States. In American Jewish Yearbook, ed. David Singer, vol. 96, 51–101. New York: American Jewish Committee.

Goldberg, J.J. 2011. Day schools stuck in neutral. Forward, December 29th.

Guarnizo, Luis E., and Michael P. Smith. 1998. The location of transnationalism. In Transnationalism from below, eds. M.P. Smith, and L.E. Guarnizo, 3–34. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Held, David, Anthony McGrew, David Goldblatt, and Jonathan Perraton. 1999. Global transformations. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Katz, Steven T. 2010. Why is America different? American Jewry on its 350th anniversary. Lanham: University Press of America.

Kearny, Michael. 1995. The local and the global. The anthropology of globalization and transnationalism. Annual Review of Anthropology 24: 547–565.

Kennedy, Paul T, and Victor Roudometof. 2002. Communities Across Borders: New Immigrants and Transnational Cultures. London and New York: Routledge.

Khagram, Sanjeev, and Peggy Levitt. 2008. Constructing transnational studies. In Rethinking transnationalism, ed. Ludger Pries. London and New York: Routledge.

Kritz, Mary M., and Douglas T. Gurak. 2005. Immigration and a changing America. In The American People, Census 2000, eds. Reynolds Farley and John Haaga, 259–301. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Levitt, Peggy, and Nina Glick Schiller. 2004. Conceptualizing simultaneity: A transnational social perspective on society. International Migration Review 38(145): 595–629.

Levitt, Peggy, and Mary Waters (eds.). 2002. The changing face of home: The transnational lives of the second generation. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Lowell, B. Lindsay, Carla Perdezini, and Jeffrey S. Passel. 2009. La demografía de la migración de México a Estados Unidos (Demographics of migration from Mexico to the United States). In La gestión de la migración México – Estados Unidos: Un enfoque binacional (Managing migration Mexico – United States: A binational approach), coord, eds. Agustin Escobar, and Susan F. Martin, 21-62. Mexico: SEGOB, CIESAS, DGE Equilibrista.

Lozano Ascencio, Fernando, and Luciana Gandini. 2012. Skilled-worker mobility and development in Latin America and the Caribbean: Between brain drain and brain waste. The Journal of Latino-Latin American Studies 4(1): 7.

Massey, Douglas S. 1987. Understanding Mexican migration to the US. American Journal of Sociology 92(6): 1372–1403.

Nonini, Douglas. 2005. Diasporas and globalization. In Encyclopedia of diasporas, eds. Melvin Ember, Carol Ember, and Ian Skoggard. New York: Springer.

Pew Hispanic Center. 2009. http://pewhispanic.org/.

Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion and Public Life. 2010. Global religion and migration database 2010. Where international migrants have gone. Migrants destinations by region. http://features.pewforum.org/religious-migration/world-maps/weighted-gone.php.

Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion and Public Life. 2012. Faith on the move: The religious affiliation of international migrants. Spotlight on the United States. Analysis March 8, 2012. The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. http://www.pewforum.org/Geography/Religious-Migration-united-states.aspx.

Phillips, Bruce. 2005. American Judaism in the twenty-first Century. In American Judaism, ed. Dana Evan Kaplan, 397–416. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Portes, Alejandro, Luis Guarnizo, and Patricia Landolt. 1999. The study of transnationalism: Pitfalls and promise of an emergent research field. Ethnic and Racial Studies 22(2): 447–462.

Pries, Ludger. 2008a. The approach of transnational social spaces. Responding to new configurations of the social and the spatial. In New transnational social spaces—International migration and transnational companies in the early twenty-first century, ed. Ludger Pries, 3–34. London: Routledge.

Pries, Ludger. 2008b. Transnational societal spaces. Which units of analysis, reference and measurement. In Rethinking transnationalism. The meso-link of organization, ed. Ludger Pries, 1–20. London: Routledge.

Rebhun, Uzi, and Lilach L. Ari. 2010. American Israelis. Migration, transnationalism and Diasporic identity. Brill: Leiden and Boston.

Reinharz, Shulamit, and Sergio DellaPergola. 2009. Jewish intermarriage around the world. New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers.

Remennick, Larissa. 2007. Russian Jews on three continents. Identity, integration, and conflict. New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers.

Robertson, Roland. 1992. Globalization: Social theory and global culture. London: Sage.

Safran, William. 1991. Diasporas in modern societies: Myths of homeland and returns. Diaspora 1: 83–99.

Sarna, Jonathan. 2005. Afterword: The study of American Judaism: A look ahead. In American Judaism, ed. Dana Eva Kaplan, 417–422. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sassen, Saskia. 2005. The Global City: Introducing a concept. Brown Journal of World Affairs, XI(2): 27–43.

Saxe, Leonard. 2010. Counting American Jewry. Sh’ma: A Journal of Jewish Responsibility. Josh Rolnick, The Sh’ma Institute, 14–15. http://www.bjpa.org/Publications/details.cfm?PublicationID=7264.

Scholte, Jan Aart. 1998. The globalization or world politics. In The globalization of world politics. An introduction to international relations, eds. John Baylis and Steve Smith. London: Oxford University Press.

Senkman, Leonardo. 2008. Klal Yisrael at the frontiers: The transnational Jewish experience in Argentina. In Jewish identities in an era of globalization and multiculturalism, ed. Judit Bokser Liwerant et al., 125–150. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Sheffer, Gabriel. 1986. A new field of study: Modern diasporas in international politics. In Modern diasporas in international politics, ed. Gabriel Sheffer, 1–15. London: Croom Helm.

Sheskin, Ira M. 2004. Population study of the Greater Miami Jewish Community. Miami: Greater Miami Jewish Federation.

Sheskin, Ira, and Arnold Dashefsky. 2011. Jewish Population in the United States, 2011. Current Jewish Population Reports. North American Jewish Data Bank. http://www.bjpa.org/Publications/details.cfm?PublicationID=13458.

Shoham, Snunith, and Sarah Kaufman Strauss. 2008. Immigrants’ information needs: Their role in the absorption process. Information Research 13: 4.

Tölölyan, Khachig. 1996. Rethinking diaspora(s): Stateless power in the transnational moment. Diaspora 5(1): 3–36.

Tolts, Mark. 2011, November 14. Demography of the contemporary Russian-speaking Jewish Diaspora. Paper presented at the conference on the Contemporary Russian-speaking Jewish Diaspora, Harvard University, Cambridge.

Topel, Marta F. 2005. Jerusalém & São Paulo: A nova ortodoxia Judaica em cena. Rio de Janeiro: Topbooks Editora.

Ukeles, Jacob B., and Ron Miller. 2003. The Jewish Community Study of San Diego. San Diego: United Jewish Federation of San Diego County.

UNESCO-ISSC. 2010. World Social Science Report. Knowledge Divides.

United Nations, Human Development Programme. 2009. Human Development Report 2009. Overcoming barriers: Human mobility and development. New York: United Nations. http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/HDR.

Vaad Hajinuj, 2005. Education figures. Buenos Aires: AMIA.

Van Hear, Nicholas. 1998. New Diasporas: The mass exodus, dispersal and regrouping of migrant communities. Issue 2 of Global Diaspora Series. London: Taylor and Francis Group.

Vertovec, Steven. 2009. Transnationalism. London and New York: Routledge.

Waters, Malcom. 1995. Globalization. London: Routledge.

Waxman, Chaim. 1983. American Jews in transition. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Woocher, Jonathan S. 1986. Sacred survival: The civil religion of American Jews. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Woocher, Jonathan S. 2005. Sacred survival revisited: American Jewish civil religion in the new millennium. In American Judaism, ed. Dana Evan Kaplan, 283–297. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sobel, Julie. n.d. US Latins celebrate long-hidden Jewish roots. http://journalism.nyu.edu/publishing/archives/livewire/archived/us_latins_celeb/index.html.

Yúdice, George. 2003. The expediency of culture: Uses of culture in the global era. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Zlotnik, Hania. 1999. Trends of international migration since 1965: What existing data reveal. International Migration 37(1): 21–61.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Yael Siman for her invaluable collaboration, research assistance, and thoughtful insights. Anonymous reviewers provided very useful comments and suggestions with respect to this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is related to a global research project that advances a transnational perspective to study Latin American Jewish life in the region and abroad: “Latin American Jews in a Transnational World: Redefining Experiences and Identities in Four Continents” outlined by Judit Bokser Liwerant, Sergio DellaPergola, and Leonardo Senkman (2010).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liwerant, J.B. Latin American Jews in the United States: Community and Belonging in Times of Transnationalism. Cont Jewry 33, 121–143 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12397-013-9102-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12397-013-9102-x