Abstract

Anthropomorphism represents a central theoretical term in social robotics and human robot interaction (HRI) research. However, the research into anthropomorphism displays several conceptual problems that translate into methodological shortcomings. Here we report the results of a scoping review, which we conducted in order to explore (i) how the notion of ‘anthropomorphism’ is understood in HRI and social robotics research, and (ii) which assessment tools are used to assess anthropomorphism. Three electronic databases were searched; two independent reviewers were involved in the screening and data extraction process; a total of 57 studies were included in the final review which encompassed 43 different robots and 2947 participants. Across studies, researchers used seven different definitions of anthropomorphism and most commonly assessed the phenomenon by use of amended versions of existing questionnaires (n = 26 studies). Alternatively, idiosyncratic questionnaires were developed (n = 17 studies) which, as a qualitative thematic analysis of the individual questionnaire items revealed, addressed nine distinct themes (such as attribution of shared intentionality, attribution of personality etc.). We discuss these results relative to common standards of methodological maturity and arrive at the conclusion that the scope and heterogeneity of definitions and assessment tools of anthropomorphism in HRI hinders cross-study comparisons, while the lack of validated assessment tools might also affect the quality of results. To nurture reflection on these methodological challenges and increase comparability within the field we conclude by offering a set of reporting guidelines for research on anthropomorphism, as a first constructive effort to facilitate a coherent theory of anthropomorphism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This study is a contribution to the ongoing effort—in HRI research and social robotics—to reflect on the methodological foundations of these young multidisciplinary research areas. From its outset, about 15 years ago, a central investigative focus in HRI has been on human interactions with so-called “social” robots—a class of robots that are designed to engage people in distinctively social interactions, and to invite perceptions as social interaction partners rather than as instruments. That robots can elicit such reactions from humans did not appear surprising to the early protagonists of “social robotics”, who saw here another instance of a phenomenon highlighted by Reeves and Nass as the so-called “media equation”, and turned this into a new design strategy:

People are attracted to life-like behavior and seem quite willing to anthropomorphize nature and even technological artifacts [...]. We tend to interpret behavior (such as self-propelled movement) as being intentional, whether it is demonstrated by a living creature or not [1]. When engaging a non-living agent in a social manner, people show the same tendencies [2]. Ideally, humans would interact with robots as naturally as they interact with other people. To facilitate this kind of social interaction, robot behavior should reflect life-like qualities ( [3] , p. 8f).

Since this early vision of human social interactions with robots, the relationship between, on the one hand, the “life-like qualities” of a robot and, on the other hand, the human tendency to “anthropomorphize—i.e., to treat the robot as an individual with human-like qualities and mental states” ([3], p. 236)—has been a subject of intense investigation in social robotics and HRI. While the past one and a half decades of HRI research have revealed the complexity of the phenomenon—showing dependencies on, e.g., sensory modality, framing of robot, interaction context, or personality—in the course of these investigations the terminological clarity has become challenged. This is partly due to an ambiguity of the noun “anthropomorphism”, which carries different meanings for different researchers. Thus, while some take the noun to denote the ‘human tendency to anthropomorphize’, for others the noun belongs with the adjective ‘anthropomorphic’ and characterizes the appearance (physical or kinetic) of a robot as assessed by the roboticist. Moreover, the scope of the ‘anthropomorphic’ features of a robot, as characterized in descriptions of experimental setups, varies between “life-like” and “human-like”, while ‘anthropomorphizing’ focuses on exclusively “human-like” capacities. The potential conceptual and methodological problems introduced by this ambiguity of the term ‘anthropomorphism’ do not seem to have received much attention [4]. In fact, occasionally formulations display—or at least invite—terminological confusions. For example, a study investigating the human tendency to anthropomorphize a certain device is announced as “a study on anthropomorphism of a receptionist robot” ( [5], p. 236); or again, authors investigate reactions to an anthropomorphic/human-like robot but describe their target as human “impressions and behaviors toward anthropomorphized artifacts” ([6], p. 934; emphasis added). In addition, while an extensive analytical research debate about the content and implications of the descriptor ‘human-like’ appears to be missing, a host of different measures of human reactions are in use, suggesting implicit conceptual variations.

Given the centrality of the phenomenon of anthropomorphizing for social robotics, it is important, we submit, to investigate whether observations of terminological uncertainties should be counted as sporadic linguistic infelicities or should be taken to be indicative of a more pervasive methodological problem. A scoping review can help answer this question as this method offers a panoramic summation of evidence for a given research question [7]. A scoping review can have various objectives; presently, the focus is on describing the definitions, assessments, and conceptual understandings of anthropomorphism as used in HRI research. Thus, the scoping review does not offer an answer to the specific question of what anthropomorphism is and how it should be assessed but rather describes the empirical and conceptual landscape within the field.

That the focus on anthropomorphism is of central methodological significance is also borne out by most recent developments of classificatory tools (e.g., [8]), meta-analytical synopses [9] or measuring techniques [10] for human reactions to robots that are focused on or include anthropomorphism. The significance of these proposals hinges on whether the notion of anthropomorphism that is modeled in these contributions captures, deviates from, or improves on the understanding of the term ‘anthropomorphism’ in state of the art of HRI or social robotics research. Here a scoping review can provide useful clarifications. For instance, Onnash and Roesler [8] offer a taxonomy for human–robot interaction that operates with three classificatory dimensions, the interaction context, the features of the robot (physical, kinematic, functional), and the “team classification” (p. 841), i.e. a classification of the interactional roles (supervisor, collaborator, bystander etc.) performed by the human(s) interacting with the robot. This classification helpfully provides “predefined categories to enable structured comparisons of different HRI scenarios” (p. 837) and thereby enable a more differentiated discussion of studies on human reactions to robots, as well as of some studies on the phenomena labeled “anthropomorphism” in the literature. But the scope, and thereby also the relevance, of the proposed classification is not discussed. For this purpose, one would need to clarify (a) whether the specification of interactional roles is sufficiently strong to cover phenomena of anthropomorphizing at more fine-grained levels of human experience, as well as (b) whether such more fine-grained differentiations of the human tendency to anthropomorphize have been considered an important investigative target in the anthropomorphism literature in HRI. Our study here can clarify this latter task (b), which is prerequisite for evaluating the scope and relevance of the suggested taxonomy in application to HRI research on anthropomorphism, its prime illustration.

In short, scoping reviews can usefully support the evaluation of constructive proposals for new definitions or models of a theoretical construct. With these auxiliary functions in mind, we thus present a scoping review of relevant contributions to HRI research in order to arrive at a better understanding of the methodological status of ‘anthropomorphism,’ a key notion of current HRI research. As our results show, greater attention to the definition and use of the term ‘anthropomorphism’ is not only required for the sake of good terminological housekeeping, but also promises broader methodological advancement, providing new leads towards development of improved and standardized measures. A similar endeavor was recently undertaken in a review of anthropomorphism in AI enabled technologies (mainly chatbots, smart speakers), where the authors conclude that there is a need for theoretical and operational clarity of the concept of anthropomorphism. Unfortunately, it is not clear to what extent the conclusions extend to research on embodied technology (as the majority of their included records were non-embodied, AI enabled technology) [11]. Recent “models” and identification of “points of contention in the employment of the term ‘anthropomorphism’ that call for clarification” [12] document an increasing perception among HRI researchers that it is time to critically reflect this central theoretical construct of HRI research. While individual literature reviews may also offer important insights for this purpose, a systematic scoping review anchors the assessment of conceptual divergences with greater empirical validity.

2 Research Questions

The main research questions governing this scoping review are as follows:

-

1.

How is the notion of ‘anthropomorphism’ understood in HRI and social robotics research (relative to the selected body of literature)?

-

2.

Which assessment tools are used in HRI and social robotics research to assess anthropomorphism?

While HRI and social robotics research are characterized by different targets and methods, we will, for ease of reference, in the following use ‘HRI’ (research) to cover both areas.

3 Methods

The protocol of the present scoping review was pre-registered in Cadima (under the title: “Assessment of anthropomorphism in HRI”), an open-source evidence synthesis tool.

Three electronic bibliographic databases were searched for relevant publications: IEEE, COMPENDEX, and ACM Digital Library in March 2021. The search strategy was established through team discussions and finally reviewed by an experienced librarian. The final search string drew on the SPIDER criteria: S (sample) PI (phenomenon of interest), D (design), E (evaluation), R (research type) [13]. Given the variety of research designs utilized in HRI, the SPIDER criteria were a better match for the goal of the present review than the more familiar PICO criteria mainly used in intervention research (P: patient/population; I: intervention; C: comparison; O: outcome) or the PCC (P: population; C: content; C: context) criteria more often used in scoping reviews. To increase the likelihood of identifying all relevant records we did not include definitions of’Sample’ (S: for the present review: healthy adult) or’Research type’ (R: for the present review including qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods) in the search string. However, for’Sample’ (S) we specified that children should not be included. Hence, the final search string encompassed keywords on S (NOT child*) PI (robot* OR android OR geminoid OR HRI), D (questionnaire* OR surv* OR interview OR focus group OR case OR stud* OR observ*), E (anthrop*). The search strategy was employed for each of the three electronic databases independently using the Boolean operators. Due to different technological interfaces, subtle differences in the search string had to be introduced into the search string to capture all relevant publications in each database. For the full list of search strings see "Appendix 1".

Following the search in the databases, all the identified publications were exported to the reference-management software Zotero, imported into Cadima, and were first screened at the title and abstract level independently by two authors (MJH and OQ) in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria to be detailed presently. An initial consistency check was conducted after n = 30 records to ensure that the ratings were consistent by the two raters. Following the abstract and title screening, the remaining publications were full text screened independently by the same two raters. Reasons for exclusion were noted for each excluded publication at both the abstract-title and full text screenings, and any disagreements on eligibility were discussed and resolved within the group of authors.

We used the following inclusion and exclusion criteria to set the boundaries for the review. To render inclusion in the present review, the following inclusion criteria had to be met: the study should include (i) healthy adults (over the age of 18), (ii) interaction with a physical robotic agent with some movement or acoustic ability that enable direct interaction (or the experience thereof), (iii) explicit reference to the notion of anthropomorphism and a systematic assessment (observational or questionnaire/interview) of the human disposition for projecting human characteristics onto the agent, (iv) an empirical investigation including controlled/uncontrolled trials, case studies, focus groups, interviews, surveys, experiments, writing tasks, field studies etc., (v) published as an empirical research paper or extended abstract in peer-reviewed journals/proceedings; vi) published in English. Studies meeting any of the following criteria were excluded: (i) studies with adults with severe cognitive impairment (such as severe developmental disorders or neurodegenerative diseases), (ii) use of a non-physical agent or telephone or stand-alone virtual agents (such as ALEXA) unless used as a comparative condition to a physical robotic agent, (iii) assessment of `anthropomorphism´ solely as an intrinsic quality of the agent, (iv) narrative or systematic reviews, research protocols, grey literature, short conference abstracts (less than 2 pages).

3.1 Critical Appraisal

The included studies were quality rated in line with the methodology for conducting scoping reviews (although it is not mandatory to include, see [14]). The aim of critical appraisal is to systematically identify strengths and weaknesses in the included records and make visible any potential sources of bias (such as threats to generalizability, validity and so forth) [15]. In the development of appraisal criteria for the present review, we sought to embrace the diversity of research traditions from which the included studies stem. Given the heterogeneity of the research methods employed within HRI research, we could not adhere to any of the full critical appraisal tools traditionally used but strived to use sub-items that the tools share with one another (see [15] for overview and open access tools for conducting critical appraisals within eight different methodologies).

Thus, the following criteria were assessed on a three-point rating scale (no, undetermined, yes; scale 0–2): (1) Is the research question or aim clearly stated?, (2) Is the recruitment strategy appropriate for the research aim?, (3) Have basic characteristics of the population been described?, (4) Is the procedure well described?, (5) Was sample size determined based on a priori power analysis (not rated for qualitative studies)?, (6) did it include a well-defined description of the assessment of anthropomorphism?, (7) did the authors report on potential conflicts of interest? In total the critical appraisal rendered a maximum score of 14 (12 for qualitative studies).

3.2 Data Extraction

From each included record we abstracted data on publication characteristics (year of publication, country), sample characteristics (sample size, where the population was drawn from, gender distribution, age (M, SD; range)), research design, research hypothesis, overall results, definition of anthropomorphism utilized in paper, assessment tool for assessing anthropomorphism, and robot characteristics (name, manufacturer of robot utilized in the study). Importantly, data was only extracted if it pertained to anthropomorphism. Thus, data extraction was only performed on the research hypothesis and assessment tools that related to anthropomorphism from the included records.

4 Results

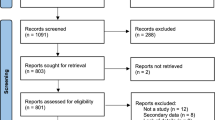

The literature search in the three databases yielded a total of n = 2031 records as seen in the PRISMA flow diagram in Fig. 1. After duplicates were removed, 1499 records remained. An initial consistency check was conducted for the screening of the first 30 records, yielding an excellent Kappa value of 0.84.Footnote 1 Following title and abstract screening, a further 1329 records were removed as not compliant with the above stated selection criteria, leaving 170 for full-text screening. Following the full-text screening an additional 113 records were excluded (see Fig. 1 for reasons), leaving a total of 57 publications included in the present review.

4.1 Sample and Study Characteristics

For an overview of the characteristics of the 57 included records see Table 1. In total, the 57 included publications encompassed N = 2947 participants whereof n = 1082 were male and n = 1277 were female. The genders of the remaining participants (n = 588; 20% of the total participant pool) were not disclosed in the publications (11 publications). Thirty-nine (68%) of the 57 publications reported the mean age of the participants. The mean age across these publications was 27.14 years (range 18–91 years). Standard deviations were disclosed in 25 publications (44%). Importantly, the lower age range was predefined by the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the review (i.e., healthy adults over the age of 18 years). In 17 publications (30%) it was not explicitly described how the participants were recruited, 19 (33%) of the studies recruited amongst the student population, and 21 (38%) studies had other recruitment procedures.

The majority of the included publications encompassed laboratory studies (48 studies; 84%), whereof 34 (70%) had a between subjects-design, 11 (24%) had a within-subjects design, 2 (4%) were qualitative laboratory studies, and the remaining one study (2%) did not include any comparator. Four (7%) of the included 57 publications described field studies, 1 (2%) described an fMRI study, and the remaining 5 studies (9%) included other designs. Most studies were from the continents of Asia (27%; 15 studies which 11 were from Japan), North America (20%; 11 studies) or Europe (22%; 13 studies, with 8 stemming from Germany). Four studies (7%) were from Oceania and three studies were conducted on multiple continents (6%). It was unclear where the remaining 11 (20%) studies were conducted.

As illustrated in Fig. 2, relative to the pool of studies reviewed, there appears to be a surge of interest in researching anthropomorphism. Given that inclusion of a physical robot is an inclusion criterion for the present review, this increase could also simply reflect the increased availability of robots.

4.2 Results of Critical Appraisal

The results of the critical appraisal can be seen in Table 2. A large proportion of studies do not report on key elements of research ethics in their dissemination of results, which makes is difficult to ascertain to what extent participants could have been coerced or could have entered the study on an uninformed basis. Only three of the 57 studies reported on potential conflicts of interest (question 1 in Table 2). Declaring conflicts of interests is particularly important for research undertaken by institutes from the private sector, but conflicts of interest should be declared regardless of whether they are present or not, and independently of the journal’s policy to support this element of research methodology explicitly in the course of the submission procedure.

For some studies (n = 28) it was difficult to determine if the recruitment strategy was appropriate to obtain the kind of knowledge necessary to answer the research question (Table 2, question 7). This was due to inadequate information on how the participants were recruited—who, or how many, chose, or refused, to partake after being asked, how potential participants were approached, how and if they were compensated for participation, and so forth. For instance, it remains unclear if results might have been influenced by whether students were approached directly in class by their own lecturer (as opposed to reacting to recruitment posters put up on campus), and whether compensation via course credit, raffle tickets, or monetary reward could have affected motivations. Additionally, only four of the reviewed studies based recruitment on a priori sample size calculations (question 3, Table 2). Hence, it is difficult to ascertain if the studies have sufficient statistical power to ensure that effects did not occur by chance.

The description of some basic characteristics of the participation pool (question 4 below in Table 2) and of study procedures (question 5 below in Table 2) were more detailed. Importantly, however, we approached question 4 very leniently and only required the studies to report some descriptive information on the participants (so for instance if age range was reported, 2 points were given even if the mean age of the sample was not reported). With very few exceptions the research goals (question 6) and descriptions of how anthropomorphism was assessed (question 2) were adequately reported.

4.3 Types of Robots used in Studies Assessing Anthropomorphism

An overview of the robots included in the studies can be seen in Table 3. A total of 43 different robots were used—ranging from robots with entirely non-humanoid physical shape and interaction repertoire designed only for functionality (such as the Roomba), to robots with humanoid physical shape and interaction repertoire explicitly designed for social interaction with humans. Besides commercially available robots, some studies (n = 9) used robots constructed by the researchers themselves (e.g., prototypes). The single most frequently used robot in the included studies is Softbanks’ NAO robot (n = 12). The vast majority of studies included only a single robot (43 studies: 75%). Four studies (7%) included interaction on screen (laptop) as a control condition in their experiment. Six studies (11%) used humans as a control condition.

4.4 How Anthropomorphism is Defined

Very broadly speaking, the included records can be sorted into five categories relative to how they approach the task of defining anthropomorphism. As can be seen in Table 4, the dominant approach (definition 0) seems to be to use term 'anthropomorphism' without defining it, on the implicit assumption that a shared conceptual consensus exists. The second most common approach consists in using and quoting the definition—or minor variations thereof—offered by Epley and colleagues [72]:

Imbuing the imagined or real behavior of nonhuman agents with humanlike characteristics, motivations, intentions, and emotions is the essence of anthropomorphism. These nonhuman agents may include anything that acts with apparent independence, including nonhuman animals, natural forces, religious deities, and mechanical or electronic devices (pp. 864-865).

For ease of reference, we label the various definitional strategies relative to the focus of the definition; since the focus of the second approach is on anthropomorphism as attribution, we call this definition the “attribution-focused definition (definition 1)”. Some studies adhere to the attribution-focused definition but elaborate it by highlighting specific functions of anthropomorphism. For instance, that anthropomorphism acts as a hypothetical mechanism of inverse dehumanization [27], or that it increases the ability to predict and explain the behavior of non-human agents [17]—the so-called “effectance motivation factor” from the model of anthropomorphism suggested by Epley and colleagues [72]. Others elaborate some aspects left open by the attribution-focused definition, accentuating for instance that the “apparent independence” is a form of acting that allows the human ‘user’ to take the so-called “intentional stance” (introduced into common parlance by D. Dennett [73]) of interpretation, i.e., to view the behavior as intentional [66].

Some researchers define 'anthropomorphism' as a noun that relates to the predicate 'anthropomorphic' understood as denoting a quality of the physical shape of a robot—let's call this the robotic feature-focused definition (definition 2)—and test to what extent participants ascribe this quality by way of assenting to common-sense descriptions such as "human-like shape" or "human-like appearance". Occasionally, on this understanding of anthropomorphism as a characterization of robotic features, behavioral features of the robot are also included, as for instance, seen in the following passage: “Anthropomorphism of an entity refers to how human-like it is in appearance (e.g., has eyes) or behavior (e.g., has good etiquette)” ([49], p. 2).

Another common approach, which we call the definition by imported construct (definition 3), is to cite the publication from which the Godspeed Questionnaire Series (GQS) stems, in order to import implicitly or explicitly the definition of anthropomorphism stated there: “Anthropomorphism refers to the attribution of a human form, human characteristics, or human behavior to nonhuman things such as robots, computers, and animals” ([75], p. 74. However, it has been pointed out that the GQS questionnaire mainly focuses “on the development of uncanny valley indices” ([9], p. 840). So, the definitional focus of the GQS questionnaire is not sufficiently narrow to be classified as an attribution-focused definition of anthropomorphism (definition 1 above). A few studies offer definitions that seem to be inspired by one or more of the aforementioned approaches but end up operating with idiosyncratic modifications or combinations without anchoring these in citations. This strategy we label narrowed attribution-focused definition (definition 4). For instance, Ono and colleagues define anthropomorphism as: '…the idea that an object has feelings or characteristics like those of a human being. In other words, it means that humans regard the object as a person to communicate with, and moreover try to read its mind' ([50], p. 335).

Other researchers idiosyncratically introduce a focus on the process of anthropomorphism and characterize it as a psychological mechanism that serves to increase predictability and reduce uncertainty [36]. This strategy we call the process-focused definition (definition 5).

Finally, some authors emphasize special functional aspects of anthropomorphism, operating independently of Epley et al. (quoted above, definition 1), and thus in effect pursuing a different strategy which we call the function-focused definition (definition-6). For example, here we find the claim that by ascribing intentions to robots:

It would also make it easier to form social connections with non-human agents, extending our fundamental desire for social relationships outside of humankind. Thus, anthropomorphism would appear to offer us a simpler, more familiar world that is richer in social interaction, giving us greater confidence in our interactions with it. ([68], p. 163).

Altogether, then, the 57 HRI studies reviewed here do not proceed from one, universally agreed upon standardized definition of anthropomorphism, but state their research focus in different ways with at least six semantically significant variations.

4.5 How Anthropomorphism is Assessed

An overview of the questionnaires used to assess anthropomorphism can be seen in Fig. 3 and Table 5. Most commonly, studies amended existing questionnaires to accommodate a given study objective. This was, for instance, achieved by selecting specific items from published questionnaires, adapting scales to a given culture/robot or language, or changing the rating scales of a given survey from e.g., a 7-point scale to a 5-point scale etc. Of the 26 studies (46%) that amended existing versions of questionnaires, 10 did not include other measures of anthropomorphism. Overall, 31 of the studies (54%) included only one anthropomorphism questionnaire while 17 of the included studies (30%) included two questionnaires, and nine studies (16%) included three or more different questionnaires. Ten studies solely assessed anthropomorphism with questionnaires developed for the specific study.

Overview of the questionnaires used in the included studies. Abbreviations and references: GQS: the Godspeed Questionnaire series [69]; Human nature attribution (several different references are given for the scale in the included records) [70,71,72,73]; IDAQ; Individual Differences in Anthropomorphism Questionnaire [74]; RoSAS:the Robotics Social Attributes Scale [75]; Mind perception [76]; Humanness index [77], IPIP:international personality item pool [78]; Inclusion of other in self scale [79]. Please note that some studies utilized more than one questionnaire whereby the number of questionnaires used exceeds the total number of studies included

4.5.1 Method 1: Assessing Anthropomorphism with Standardized Measures

As can be seen in Fig. 3 the single most used standardized assessment tool in the included studies is the GQS. The GQS is based on a collection of amended items from other questionnaires [75]. The publication in which it was first presented [75] did not include a factor analysis but high Cronbach's alpha scores for the subscales were reported. Cronbach's alpha scores is a measure of internal consistency of a test- i.e. the extent to which there is homogeneity or consistency between individual items (for discussions of the usefulness of Cronbach's alpha please see [87, 88]). The popularity of the GQS is likely due to its availability, ease of use, and the claimed breadth of concepts being assessed by the scale [89]. The scale is designed to assess five composite scores (Anthropomorphism, Animacy, Likeability, Perceived Intelligence, and Perceived Safety), where each is assessed by three to six items on five-point semantically differential rating scales (e.g., dead-alive). The subscale relating to anthropomorphism consists of five items (fake-natural; machinelike-humanlike; unconscious-conscious; artificial-lifelike; moving rigidly-moving elegantly) [75]. The GQS does not assess the attributional beliefs that a person has when engaged in interaction with a given robot but rather assesses the direct impressions that participants have of the properties of a given robot upon immediate perceptual encounter (visual and/or acoustic). Thus, it cannot be used to draw inferences about anthropomorphism as a human dispositional trait [89, 90]. Furthermore, the construct validity (i.e., the extent to which it assesses the constructs it claims to assess) of the scale has been called into question—for instance, it has been reported that the constructs are not represented independently of negative–positive affect and that there are high correlations between subscales indicating a shared underlying factor ([83], p. 1516). Thus, Ho and colleagues suggested an alternative scale that they pose as a “new measure for human perceptions of anthropomorphic characters that reliably assesses four relatively independent individual attitudes” (exploring the features of attractiveness, eeriness, humanness, and warmth ([83] p. 1516). The humanness index from this scale has been utilized as an indicator of anthropomorphism in some of the included studies (see Table 5). The humanness index is also a semantic differential rating scale with some overlap with GQS. It consists of 6 items (artificial-natural; human-made–humanlike; without definite lifespan–mortal; inanimate–living; mechanical movement–biological movement; synthetic–real) and shows good psychometric properties [83]. Carpinella and colleagues [81] also drew attention to psychometric issues with the GQS and developed the Robotics Social Attributes Scale (RoSAS), which builds on GQS items but also includes items from social cognition research. Unlike GQS and the humanness index, RoSAS consists of unidimensional items that are to be rated in a nine-point Likert scale. The items in RoSAS load on three factors: warmth (items: feeling, happy, organic, compassionate, social, emotional), competence (items: knowledgeable, interactive, responsive, capable, competent, reliable), and discomfort (items: aggressive, awful, scary, awkward, dangerous, strange). RoSAS was used in five of the included studies (see Table 5) where the factors “warmth” and” competence” have been used in assessment of anthropomorphism. However, although some authors use subscales of the RoSAS as an assessment tool of anthropomorphism, it should be empirically established if and how the subscales “warmth” and “competence” relate to anthropomorphism as RoSAS was not developed with the purpose of assessing anthropomorphism.

Four studies used the “mind perception scale” developed by Grey and colleagues [82]. Like RoSAS, this scale is also unidimensional, but it distinguishes between attribution of capacities relating to experience (items: hunger, fear, pain, pleasure, rage, desire, personality, consciousness, pride, embarrassment, and joy), and agency (items: self-control, morality, memory, emotion recognition, planning, communication, and thought). Participants are asked to compare agents on the various items—e.g., comparing which agent is more capable of feeling pain. The comparisons are made on five-point rating scales.

Several papers used the human attribution scale derived from the taxonomy proposed by Haslam and colleagues. This taxonomy distinguishes between attribution of “human nature traits” that are universal among humans (e.g. reflecting emotionality) from those that are uniquely human yet occur with individual differences, reflecting learned or achieved qualities (e.g. higher cognitive functioning). Whilst the former qualities are believed to be shared with other animals the latter are believed to separate humans from other animals. There are several variations of the scale used in the included records. For instance Salem et al. [54] utilized the ten human nature traits (e.g. curious, aggressive etc.) as an indicator of “human likeness” on a five-point Likert scale with reference to Haslam et al. 2008 [77], whilst Zlotowski et al. [70] used a seven-point Likert scale with the same ten items with reference to Haslam et al. (2006) [78]. Furthermore, Fraune et al. (2017) [29], with reference to Loghnan & Haslam [76], only asked participants to assess two of five traits—but described both human nature and uniquely human traits in their article. The human nature- uniquely human taxonomy is further elaborated with the addition of “animalistic dehumanization” and “mechanistic dehumanization” [79] under the heading of the”humanness scale” and is used in one study with a five-point Likert scale [61] whilst with a seven-point Likert scale in another [60].

The Individual Differences in Anthropomorphism Questionnaire (IDAQ) is the only questionnaire utilized in the studies that aims to assess anthropomorphism as an inherent individual tendency or dispositional trait of humans. Thus, IDAQ scores can be obtained before the actual interaction with a given robot, and aid in explaining or statistically controlling for individual variation in the tendency to anthropomorphize. However, IDAQ has been criticized for including several abstract terms that might challenge its validity—such as “free will” and “consciousness” [90, 91].

4.5.2 Method 2: Synthesis of Assessments of Anthropomorphism with Non-Standardized Measures

Some of the publications chose to construct their own questionnaires to assess anthropomorphism. The heterogeneous choices of measures made quantitative comparisons and pooling of the data challenging. Thus, in order to make this data more accessible we conducted a qualitative thematic analysis of the individual questionnaire items disseminated in the respective publications [92, 93]. The thematic analysis was made through identification and interpretation of themes in the items in these questionnaires [92]. The thematic analysis of the items (which are here quoted verbatim from the included publications) can be seen in the table of themes below (Table 6).

5 Discussion

As pointed out in the introduction, protagonists in social robotics and HRI have been proceeding for two decades from the assumption that human–robot interactions are based on the human capacity, or even tendency, to anthropomorphize. Given that the very possibility of building “social” robots, as well as most of the design questions in social robotics, depend on human capacities or inclinations that traditionally have been labeled as “anthropomorphism”, it could be expected that HRI and social robotics research have put particular focus on the methodology of research on anthropomorphizing. As our results show, however, there are several methodological difficulties that have previously only received limited attention (but see [4, 94]).

In particular, there are four challenges we wish to highlight, relating to four central elements of methodological maturity: (1) terminological standardization; (2) transparency of procedures; (3) standardized evaluation; (4) alignment of research targets and assessment tools. We discuss these four points in the following subsections, addressing (3) and (4) in the last subsection.

5.1 Terminological Standardization

Aspects of terminological standardization are degree of conceptual integration, precision, and consistency. Relative to the scope of this review, our results show that research publications on ‘anthropomorphism’ have several approaches to definitions. Thus, we identified six different definitional strategies, ranging from the simple omission of any definition or elucidation to highly idiosyncratic characterizations. This creates three substantive methodological challenges that, to the best of our knowledge, are not commented upon in the literature.

The first methodological difficulty is conceptual vagueness. The most popular of the definitions that are explicitly cited, i.e., the attribution-focused definition (definition 1) by Epley et al., is far from precise or unambiguous. The definition does not provide any details about the process by which anthropomorphizing occurs—“imbuing the imagined or real behavior” with certain characteristics left open:

-

(a)

How such a cognitive process is to work,

-

(b)

whether the imbued features have the status of, or are experienced as, fictional or real features, and

-

(c)

how, against initial plausibility, we can consider the ‘imbuing’ of further information to “imagined” behavior and the ‘imbuing’ of further information to “real” behavior indeed to be the same sort of cognitive process.

Moreover, while the definition highlights as a necessary, or at least critical, feature that the nonhuman targets of anthropomorphizing act “with apparent independence”, it remains unclear whether this requirement should be read as:

-

(d)

The perceived capacity to act independently of some mechanism or programming, and thus

-

(e)

in a random fashion, or, as the emphasis on “humanlike” characteristics would suggest,

-

(f)

in an apparently intentional, motivated, fashion.

As we noted above, three studies in our sample tried to amend the definition by removing ambiguities with respect to some of the aspects (a) and (f), for instance by describing the process as the inverse of dehumanization and requiring the ascription of intentional agency.

That Epley’s definition still has been used so pervasively, or has been replaced by a mere reference to the term (the ‘null’ approach, definition 0), might be explained by the presumption that the term ‘anthropomorphism’ has a clear definition in other disciplines and thus can be safely imported. Such cross-disciplinary terminological trust is alas ill-founded, since both in psychology and anthropology the term is explicitly contested, as brought to the fore by the longstanding debate about method in primate ethology (see e.g., [95]).

The second methodological difficulty arises from the fact that the various definitions used differ in their meanings. As already touched on above, this is evident in the case of definition 2 which characterizes not a human disposition but robotic physical features or behaviors. This ambiguity has been noticed occasionally in the literature (e.g., early on in [96]). Furthermore, definitions 2 and 3, which each merely speak of “attributions of human characteristics” to non-human objects, are sometimes (e.g., [21, 34, 48, 59, 64]) used in combination with definition 1 which, unlike definitions 2 and 3, requires in addition that the target of anthropomorphism is an “agent” whose agency is perceived as being in some fashion “independent” (see aspect ‘d’ in the previous paragraph). Researchers who exclusively rely upon definitions 2 and 3 would need to provide clear empirical examples for attributions of human characteristics to items that are not agents nor are perceived as agents, before extending the reference class of “anthropomorphism” by the use of a definition that is de facto less restrictive than their quoted sources. Definition 4 on the other hand, introduces further restrictions on the process and the content of attribution. According to our illustration for this strategy quoted above [42], the process of anthropomorphizing here occurs if and only if humans “try to read its [the object of attribution] mind” in the context of communication, which amounts to a substantive deviation from other definitions. Moreover, the content of attribution is restricted to “feelings or characteristics like those of a human being” such that the object is regarded as “a person to communicate with” (emphasis supplied). This clause thus excludes from the phenomenon of anthropomorphizing cases of attribution where a subset of human features is ascribed that as such would not suffice for personhood (for example, if the object is attributed nothing more than feelings, but not agency nor reflective consciousness, such an attribution would not qualify as a case of anthropomorphism according to definitions 1, 2, and 3). Finally, definitional strategies 5 and 6 connect anthropomorphism with certain functional advantages (e.g., predictability) or a desire for sociality. To the extent that such elaborations are not mere elucidations but are part of the explanatory category, they likewise change the meaning of the term and its application conditions relative to definition 1 which, as stated in Sect. 4.4 with reference to Table 4, is the most commonly used definition.

5.2 Discussion of Methodological Transparency

The quality rating of the included records in the present review illustrated some challenges in reporting across several studies. The field of HRI specifically investigating anthropomorphism is in its infancy as the seven different notions of anthropomorphism identified in this review show. Because of this, a lack of conceptual standardization is to be expected. Further, it is also to be expected that such a lack of standardization will be remedied in due course by both an increase in number of studies and literature reviews such as the current one. The progression to standardization can be fostered by methodological practices which enable replication of studies on anthropomorphism. In the present review we find a lack of a consensus on the target being measured i.e. anthropomorphism. A separate finding is the relatively high percentage of the studies (21–58%) not fully describing their samples in terms of age (mean, SD, range) and gender distribution. At first glance the specific demographic constitution of a research sample may seem unimportant for assessment of anthropomorphism. However, age and gender has previously been found to affect attitudes towards robots and similar psychological aspects of experiences in human–robot interaction [97]. Thus, to fully be able to understand the extent to which findings are applicable across genders and ages it is important to describe such details (or explicitly address why demographic information is deemed unimportant). This recommendation is in line with a recent review on reporting in HRI [98] and is further underlined by the replication crisis observed in several research fields [99]. Thus, not only is it important to arrive at a standardized notion of anthropomorphism such that studies can measure the same phenomenon. It is also important that research practices be upheld; even if agreement on anthropomorphism is achieved. If the research practices of those studies do not lend themselves well to replication one cannot be sure that what is being measured has the effect the studies suggest. In medical and social science research, exhaustive descriptions of demographic information are usually provided to ensure adequate data to replicate any given study and to enable readers to ascertain the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, solid descriptions of demographic information also allow for data synthesis across studies and for secondary analysis, such as meta-analysis [100], to be conducted. This “code of conduct” does not appear to be fully integrated in the research included in the present review. Furthermore, the cultural and ethnic backgrounds of samples are seldom mentioned, even though research indicates that such factors can have great influence on various aspects of the interaction between human and robot [101, 102].

5.3 Discussion of Assessment Tools of Anthropomorphism in HRI

HRI research is a fairly new research field and, as other research traditions before it, finds itself in a double bind regarding assessment tools: there is a great need for validated and standardized contemporary assessment tools, but at the same time the conceptual knowledge on which such measures should be developed needs to be obtained. Traditionally, this conceptual knowledge would, at least in part, be obtained with the aid of systematic research via, for instance, questionnaires. Thus, it should be asked: Are the published assessment tools that routinely are used to gauge anthropomorphism suitable instruments to reflect the way anthropomorphism is understood now? In view of the heterogeneity of the current conceptualizations of anthropomorphism and the multiplicity of non-standardized assessment tools, the risk of misaligning research target and assessment tools is considerable in the current situation. This is particularly striking in cases where the ‘null-definition’ of anthropomorphism is used, i.e., where researchers proceed from the presumption that the notion of anthropomorphism is a commonly understood technical term of the debate and adopt one of the ‘standardly used’ questionnaires. But the risk of misalignment arises also due to inherent features of the currently available assessment tools.

For instance, several studies have revealed problems with the conceptual validity of the GQS (see e.g. [81, 83]) indicating conceptual overlap between animacy and anthropomorphism (there is also one questionnaire item—artificial-lifelike—that is present on both scales); moreover, in one study it was concluded that GQS subscales “…are not appropriate as distinct concepts for evaluating anthropomorphic agents” ([103, (p. 1518). Furthermore, recently Kaplan and colleagues reported that the word pairs used in the GQS are not full semantic opposites, and that individual biases towards selecting certain scores may influence results [104]. However, they advocate that GQS is still a valid instrument if the rating tendency of participants and situation-specific factors are taken into consideration [104]. It should be underlined that despite the wide use of the GQS the psychometric properties of the scale are largely unknown.

However, with regard to the psychometrically tested questionnaires, such as RoSAS and the Humanness Index, it is often the case that validation of scales is conducted online with video-based stimuli material. In such studies we see impressively large sample sizes and statistically viable and appropriate testing but unfortunately, it remains uncertain how results can be replicated in a real-life setting. It is conceivable that the response behavior of participants will change depending on whether it is a real-life setting or online study, and it cannot be dismissed that not only the magnitude of responses will change (i.e. how high or low a rating is) but also the way in which responses are distributed within and across factors. Thus, questionnaires that are solely developed and psychometrically tested in an online format should ideally also be re-assessed in settings where participants engage in direct interaction with a robot.

A great number of the included records adapted existing questionnaires, and often without describing how they were changed. This is problematic as the transparency within, and comparability across, studies is reduced, and the psychometric properties of the scale are potentially changed. This is also the case if the answer format of a questionnaire is changed (e.g., from a seven-point to a ten-point Likert scale) or if items are omitted from a questionnaire. For the studies that translated and adapted questionnaires into other languages it is important to describe this adaptation process in order to assess ‘equivalence’ between questionnaires. For instance, the actual meaning of a questionnaire item can be inadvertently changed by verbatim translation. This is beautifully illustrated by Hox ([105], p. 58), who showed how the verbatim translation of ‘happiness’ from English to Dutch (geluk) would lead to an examination of ‘luck’, as the Dutch word for happiness encompass both luck and happiness (which would not be the case in English). Thus, in such an example, results would be difficult to compare.

The scarcity of validated, psychometrically tested questionnaires, combined with the increased complexity of the phenomena pursued in HRI research, are likely the source of the wealth of questionnaire items being designed for specific studies. The thematic analysis of these items (see Table 6) reveals the great bandwidth of the current understanding of the term “anthropomorphism”. Thus, the questionnaire items vary in complexity and target—ranging from ascription of cognition, emotion, agency, responsibility, relational feelings etc. to estimation of human likeness of appearance, voice and behavior. This heterogeneity in the assessment of anthropomorphism in and of itself increases the possibility of misalignment of research target (definition of anthropomorphism) and assessment tool, and challenges the possibility of comparing studies as they might not tap into the same aspect. Furthermore, some of the developed questionnaires may unfortunately be very difficult to interpret and utilize across studies. For instance, several of the questionnaire items refer to complex and vague concepts. Vagueness introduces error in measurement, as variations in the understanding of a given item (or concept) may result in measurement error within and across studies that are thus due to variations in understanding rather than ‘true differences’. For instance, one item reads “On a scale of 1 to 5, 5 being extremely human, how human did you find the robot's behavior [16]?”, without delineating, however, how behavior should be construed (i.e. movement, interactions, nonverbal communication, level of perceived social abilities etc.). Likewise, several studies refer to ‘personality’, ‘will’, ‘intelligence’, ‘mind’ which are all vague theoretically derived concepts. Given the complexity of these concepts it is unlikely that the ascription of e.g. ‘will’ to a robot can be fully explored by a single questionnaire item.

In other cases, it is not the vagueness of the concepts posing a challenge for alignment but also the overall formulations of items, as they render answers potentially irrelevant for the research target of the study. For example, item VI.1, “do you ever project personality?” may be intended to gauge the participants’ self-reported tendency to anthropomorphize but since nature and target of the projection are left unspecified, participants may report on their perception of human interagents.

A different, but related, set of problems arises due to the fact that social cognition is a highly complex affair which we intuitively navigate without being guided by differentiated common sense terminology. An item that explores whether a participant “ [is] sorry that” X did not achieve Y (see VIII.1 above) does not allow the researcher to clarify whether the participant felt affective empathy or sympathy—two different emotional states with different implications for the moral status of the robot [106]. Similarly, consider the last sentence in VIII.1, “I am proud that Eddie did not guess my person”, indicating the level of pride in winning over the robot. This item can reveal that the participant has cognitive empathy (i.e., that the participant believes that the robot tried to win), but it does not need to be an indicator for anthropomorphism, since the participants may also report here self-centered pride about their victory over an agent without any human characteristics.

5.4 Suggested Reporting Guidelines

Based on the discussion of the previous section, where we highlighted challenges with conceptual consistency, conceptual vagueness, methodological transparency, and alignment of assessment tools in current HRI research on ‘anthropomorphism’, we propose a series of reporting guidelines (see Table 7). The guidelines sum up what researchers are advised to include in their publications based on the scoping review to increase transparency and replicability. Thus, they are similar to overall guidelines on how to report on research but may still be a beneficial checklist for such a young research field. This is offered in a constructive spirit, as an effort to assist further research and the guidelines should be construed as draft guidelines to be informed and amended by future discussion and research.

6 Limitations

Several limitations should be underlined. Firstly, the conceptual unclarity that characterizes anthropomorphism also spills into the review as we utilized the search term “anthro*” which does not necessary pick up studies that examine related terms such as tendency to ascribe emotion, sociality, “interaction potential” or similar. Furthermore, the distinction between anthropomorphism and related but likely conceptually distinct terms such as ‘social presence’, ‘familiarity’ and ‘animacy’ is also unclear. Secondly, for purely practical reasons we had to limit our search to publications in English whereby important contributions in other languages could have been missed. Thirdly, many of the procedures utilized in the present review originally stem from medical sciences and intervention research (e.g., quality control ratings, reporting guidelines etc.). HRI research is a relatively new, highly interdisciplinary research field and as such represents many different research traditions that are challenging to fit into the ‘template’ offered here. Fourthly, we focused on assessment of anthropomorphism via questionnaires thereby excluding other research tools. Future reviews could focus on how anthropomorphism is assessed with other assessment tools such as neuroimaging techniques, eye tracking equipment and similar methods. Finally, the review was narrowed in several ways. For instance, children were excluded because assessment tools developed for children might be difficult to compare to, and create synthesis with, assessment tools developed for adults. Furthermore, due to the risk of interference on results from severe cognitive decline, we also excluded studies with clinical samples (such as developmental disorders and neurodegenerative diseases). Furthermore, we included only studies in which participants directly engaged with a physical robotic agent with some movement or acoustic ability whereby direct interaction (or the experience thereof) was possible. Sharing a physical space with an embodied agent has been shown to evoke phenomenologically different experiences that are difficult to compare to simply engaging in interaction via screen or observe prerecorded interactions [107,108,109]. However, in order to explore the full breadth of the conceptual understanding and methodological operationalization of anthropomorphism future reviews should also explore these aspects.

7 Conclusion

The scoping review presented in this paper examined the definitions, reporting practices, and primary assessment tools, i.e., questionnaires, of recent work in HRI research on “anthropomorphism”, revealing that this research target is not fully mature in conceptual and methodological consistency and precision. Given the complexity of human interactions with robots it is hardly surprising that the conceptual landscape of HRI research has many unclear and overlapping terms such as anthropomorphism, human likeness, sociality, animacy, mind perception, social presence, and so forth. In this paper we aim to contribute to the ongoing effort of improving the methodological foundations of HRI, undertaking five steps. The first step towards conceptual clarity is to highlight current research practices, which we have undertaken here together with step two, a suggestion of reporting guidelines. In combination with step three, a clarification of the conceptual dimensions of “anthropomorphism”, which is the focus of our current and future work, we hope to contribute to a solid operationalization and development of standardized assessment tools to assess the phenomenon of anthropomorphism in a sufficiently differentiated fashion that will facilitate future pooling of data across studies and enable convergence between the various lines of research into anthropomorphism. In focusing this review on the usage of questionnaires in anthropomorphism research, we have highlighted and differentiated the semantic foci of six definitional strategies currently used by anthropomorphism researchers in HRI. This consolidation and analysis of anthropomorphism assessments and definitional strategies has contributed to the clarification of the theoretical construct, thereby providing a foundation for future work to examine how more ‘objective’ measures (such as eye-tracking and EEG) can be related to the various definitional strategies.

Notes

The Kappa value signifies the interrater agreement – i.e., is a measure of agreement between two subjects on a given binary outcome. The Kappa value adjusts for the amount of agreement that would have occurred by chance alone. The maximum kappa- value is 1. Values from .8 to .1 are typically interpreted as very good agreement.

References

Premack D, Premack AJ (1995) Origins of human social competence. In: The cognitive neurosciences. The MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 205–218

Reeves B, Nass C (1996) The media equation: How people treat computers, television, and new media like real people. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Breazeal C (2002) Designing sociable robots. The MIT Press, Cambridge

KFischer K (2021) Tracking anthropomorphizing behavior in human-robot interaction. ACM Trans Hum-Robot Interact 11(1), pp 4:1–4:28. https://doi.org/10.1145/3442677

Trovato G et al (2015) Designing a receptionist robot: effect of voice and appearance on anthropomorphism. In: 24th IEEE international symposium on robot and human interactive communication, RO-MAN 2015, August 31, 2015–September 4, 2015, Kobe, Japan, 2015, vol 2015-November, pp 235–240. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROMAN.2015.7333573

Nomura T, Sasa M (2009) Investigation of differences on impressions of and behaviors toward real and virtual robots between elder people and university students. In: 2009 IEEE international conference on rehabilitation robotics, ICORR 2009, June 23, 2009–June 26, 2009, Kyoto, Japan, 2009, pp 934–939. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICORR.2009.5209626

Verdejo C, Tapia-Benavente L, Schuller-Martínez B, Vergara-Merino L, Vargas-Peirano M, Silva-Dreyer AM (2021) What you need to know about scoping reviews. Medwave, 21(02). https://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2021.02.8144

Onnasch L, Roesler E (2021) A taxonomy to structure and analyze human-robot interaction. Int J Soc Robot 13(4):833–849. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-020-00666-5

Roesler E, Manzey D, Onnasch L (2021) A meta-analysis on the effectiveness of anthropomorphism in human-robot interaction. Sci Robot 6(58), p eabj5425. https://doi.org/10.1126/scirobotics.abj5425

Spatola N, Wudarczyk OA (2021) Implicit attitudes towards robots predict explicit attitudes, semantic distance between robots and humans, anthropomorphism, and prosocial behavior: From attitudes to human–robot interaction. Int J Soc Robot 13(5):1149–1159

Li M, Suh A (2021) Machinelike or Humanlike? A literature review of anthropomorphism in AI-enabled technology, presented at the Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. https://doi.org/10.24251/HICSS.2021.493

Bhatti SC, Robert LP What does it mean to anthropomorphize robots? Food For thought for HRI research

Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A (2012) Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res 22(10):1435–1443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452938

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E (2018) Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 18(1):143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Brice R, CASP CHECKLISTS,” CASP—Critical appraisal skills programme. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/. Accessed Jul 01 2021

Agrawal S, Williams M-A (2018) Would you obey an aggressive robot: a human-robot interaction field study. In: 27th IEEE international symposium on robot and human interactive communication, RO-MAN 2018, August 27, 2018–August 31, 2018, 307 Zhongshan East Road, Nanjing, China, 2018, pp. 240–246.https://doi.org/10.1109/ROMAN.2018.8525615

Baddoura R, Venture G, Matsukata R (2012) The familiar as a key-concept in regulating the social and affective dimensions of HRI. In: 2012 12th IEEE-RAS international conference on humanoid robots, humanoids 2012, November 29, 2012–December 1, 2012, Osaka, Japan, pp 234–241. https://doi.org/10.1109/HUMANOIDS.2012.6651526

Bartneck C, Kanda T, Ishiguro H, Hagita N (2009) My robotic doppelganger: a critical look at the uncanny valley. In: 18th IEEE international symposium on robot and human interactive, RO-MAN 2009, September 27, 2009–October 2, 2009, Toyama, Japan, pp 269–276. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROMAN.2009.5326351.

Castro-Gonzalez A, Admoni H, Scassellati B (2016) Effects of form and motion on judgments of social robots’ animacy, likability, trustworthiness and unpleasantness. Int J Hum Comput Stud, vol 90, p. 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2016.02.004

Chun B, Knight H (2020) The robot makers. ACM Trans Hum-Robot Interact, 9(3). https://doi.org/10.1145/3377343

de Kleijn R, van Es L, Kachergis G, Hommel B (2019) Anthropomorphization of artificial agents leads to fair and strategic, but not altruistic behavior. Int J Hum Comput Stud 122:168–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2018.09.008

Deshmukh A, Craenen B, Vinciarelli A, Foster ME (2018) Shaping robot gestures to shape users perception: The effect of amplitude and speed on godspeed ratings. In: 6th international conference on human-agent interaction, HAI 2018, December 15, 2018–December 18, 2018, Southampton, United kingdom, 2018, pp 293–300. https://doi.org/10.1145/3284432.3284445

Deshmukh A, Craenen B, Foster ME, Vinciarelli A (2018) The more i understand it, the less i like it: the relationship between understandability and godspeed scores for robotic gestures. In: 27th IEEE international symposium on robot and human interactive communication, RO-MAN (2018) August 27, 2018–August 31, 2018, 307 Zhongshan East Road. Nanjing, China 2018:216–221. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROMAN.2018.8525585

Destephe M, Brandao M, Kishi T, Zecca M, Hashimoto K, Takanishi A (2014) Emotional gait: effects on humans’ perception of humanoid robots. In: 23rd IEEE international symposium on robot and human interactive communication, IEEE RO-MAN (2014) August 25, 2014–August 29, 2014. Edinburgh, United kingdom 2014:261–266. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROMAN.2014.6926263

Eyssel FA, Pfundmair M (2015) Predictors of psychological anthropomorphization, mind perception, and the fulfillment of social needs: a case study with a zoomorphic robot. In: 2015 24th IEEE international symposium on robot and human interactive communication (RO-MAN), pp 827–832

Faria M, Costigliola A, Alves-Oliveira P, Paiva A (2016) Follow me: communicating intentions with a spherical robot. In: 25th IEEE international symposium on robot and human interactive communication, RO-MAN (2016) August 26, 2016–August 31, 2016. New York, NY, United states 2016:664–669. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROMAN.2016.7745189

Fraune MR, Nishiwaki Y, Sabanović S, Smith ER, Okada M (2017) threatening flocks and mindful snowflakes: how group entitativity affects perceptions of robots. In: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM/IEEE international conference on human-robot interaction, New York, NY, USA, 2017, pp. 205–213. doi: https://doi.org/10.1145/2909824.3020248

Fraune MR, Oisted BC, Sembrowski CE, Gates KA, Krupp MM, Abanovi S (2020) Effects of robot-human versus robot-robot behavior and entitativity on anthropomorphism and willingness to interact. Comput Hum Behav, vol 105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106220

Fraune MR, Sabanovic S, Smith ER (2017) Teammates first: Favoring ingroup robots over outgroup humans. In: 26th IEEE international symposium on robot and human interactive communication, RO-MAN 2017, August 28, 2017–September 1, 2017, Lisbon, Portugal, 2017, vol. 2017-January, pp 1432–1437. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROMAN.2017.8172492

Haring KS, Matsumoto Y, Watanabe K (2013) How do people perceive and trust a lifelike robot. In: 2013 World Congress on Engineering and Computer Science, WCECS 2013, October 23, 2013–October 25, 2013. San Francisco, CA, United states 1:425–430

Häring M, Kuchenbrandt D, André E (2014) Would you like to play with me? How robots’ group membership and task features influence human-robot interaction. In: Proceedings of the 2014 ACM/IEEE international conference on human-robot interaction, New York, NY, USA, 2014, pp 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1145/2559636.2559673

Haring KS, Silvera-Tawil D, Takahashi T, Velonaki M, Watanabe K (2015) Perception of a humanoid robot: a cross-cultural comparison. In: 24th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, RO-MAN 2015, August 31, 2015–September 4, 2015, Kobe, Japan, 2015, vol. 2015-November, pp. 821–826. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROMAN.2015.7333613

Haring KS, Watanabe K, Silvera-Tawil D, Velonaki M, Takahashi T (2015) Changes in perception of a small humanoid robot. In: 6th international conference on automation, robotics and applications, ICARA 2015, February 17, 2015–February 19, 2015, Queenstown, New zealand, pp 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICARA.2015.7081129

Hasegawa R, Harada ET, Kayano W, Osawa H (2015) Animacy perception of agents: Their effects on users behavior and variability between age groups. In: 24th IEEE international symposium on robot and human interactive communication, RO-MAN 2015, August 31, 2015–September 4, 2015, Kobe, Japan, 2015, vol 2015-November, pp 106–111. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROMAN.2015.7333631

Hegel F, Krach S, Kircher T, Wrede B, Sagerer G (2008) Understanding social robots: a user study on anthropomorphism. In: 17th IEEE international symposium on robot and human interactive communication, RO-MAN, August 1 (2008) August 3, 2008. Munich, Germany 2008:574–579. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROMAN.2008.4600728

Hegel F, Krach S, Kircher T, Wrede B, Sagerer G (2008) Theory of mind (ToM) on robots: a functional neuroimaging study. In: 3rd ACM/IEEE international conference on human-robot interaction, HRI 2008, March 12, 2008–March 15, 2008, Amsterdam, Netherlands, pp 335–342. https://doi.org/10.1145/1349822.1349866

Hoffman G, Birnbaum GE, Vanunu K, Sass O, Reis HT (2014) Robot responsiveness to human disclosure affects social impression and appeal. In: 9th Annual ACM/IEEE international conference on human-robot interaction, HRI 2014, March 3, 2014–March 6, Bielefeld, Germany, 2014, pp 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1145/2559636.2559660

Kasuga H, Ikeda Y (2020) Gap between Owner’s Perceptions and Dog’s Behaviors toward the same physical agents: using a dog-like speaker and a humanoid robot. In: Proceedings of the 8th international conference on human-agent interaction, New York, NY, USA, 2020, pp 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1145/3406499.3415068

Ko S et al (2020) The effects of robot appearances, voice types, and emotions on emotion perception accuracy and subjective perception on robots. In: 22nd international conference on human computer interaction, HCII 2020, July 19, 2020–July 24, 2020, Copenhagen, Denmark, vol 12424 LNCS, pp 174–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60117-1_13

Kuhnlenz B, Sosnowski S, Buc M, Wollherr D, Kuhnlenz K, Buss M (2013) Increasing helpfulness towards a robot by emotional adaption to the user. Int J Soc Robot 5(4):457–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-013-0182-2

Kuhnlenz B, Kuhnlenz K (2020) Social bonding increases unsolicited helpfulness towards a bullied robot. In: 29th IEEE international conference on robot and human interactive communication, RO-MAN 2020, August 31, 2020–September 4, 2020, Virtual, Naples, Italy, pp 833–838. https://doi.org/10.1109/RO-MAN47096.2020.9223454

Kuhnlenz B, Kuhnlenz K, Busse F, Fortsch P, Wolf M (2018) Effect of explicit emotional adaptation on prosocial behavior of humans towards robots depends on prior robot experience. In: 27th IEEE international symposium on robot and human interactive communication, RO-MAN (2018) August 27, 2018–August 31, 2018, 307 Zhongshan East Road. Nanjing, China 2018:275–281. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROMAN.2018.8525515

Kuhnlenz B, Wang Z-Q, Kuhnlenz K (2017) Impact of continuous eye contact of a humanoid robot on user experience and interactions with professional user background. In: 26th IEEE international symposium on robot and human interactive communication, RO-MAN 2017, August 28, 2017–September 1, 2017, Lisbon, Portugal, 2017, vol. 2017-January, pp 1037–1042. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROMAN.2017.8172431

Kuzminykh A, Sun J, Govindaraju N, Avery J, Lank E (2020) Genie in the bottle: anthropomorphized perceptions of conversational agents. In: Proceedings of the 2020 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, New York, NY, USA, pp 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376665.

Li S, Xu L, Yu F, Peng K (2020) Does trait loneliness predict rejection of social robots? The role of reduced attributions of unique humanness (Exploring the effect of trait loneliness on anthropomorphism and acceptance of social robots). In: Proceedings of the 2020 ACM/IEEE international conference on human-robot interaction, New York, NY, USA, 2020, pp 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1145/3319502.3374777

Marin AL, Lee S (2013) Interaction design for robotic avatars does avatar’s aging cue affect the user’s impressions of a robot?. In: 7th international conference on universal access in human-computer interaction: design methods, tools, and interaction techniques for einclusion, UAHCI 2013, held as part of 15th international conference on human-computer interaction, HCI 2013, July 21, 2013–July 26, 2013, Las Vegas, NV, United states, 2013, vol 8010 LNCS, no. PART 2, pp 373–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-39191-0_42

Mead R, Mataric MJ (2015) Proxemics and performance: subjective human evaluations of autonomous sociable robot distance and social signal understanding. In: IEEE/RSJ international conference on intelligent robots and systems, IROS 2015, September 28, 2015–October 2, 2015, Messeplatz 1, Hamburg, Germany, 2015, vol 2015-December, pp 5984–5991. https://doi.org/10.1109/IROS.2015.7354229

Mura D, Knoop E, Catalano MG, Grioli G, Bacher M, Bicchi A (2020) On the role of stiffness and synchronization in humanrobot handshaking. Int J Robot Res 39(14):1796–1811. https://doi.org/10.1177/0278364920903792

Oistad BC, Sembroski CE, Gates KA, Krupp MM, Fraune MR, Abanovi S (2016) Colleague or tool? Interactivity increases positive perceptions of and willingness to interact with a robotic co-worker. In: 8th international conference on social robotics, ICSR 2016, November 1, 2016–November 3, 2016, Kansas City, MO, United states, vol 9979 LNAI, pp 774–785. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47437-3_76

Ono T, Imai M, Ishiguro H (2000) Anthropomorphic communications in the emerging relationship between humans and robots. In: Proceedings 9th IEEE international workshop on robot and human interactive communication. IEEE RO-MAN 2000 (Cat. No.00TH8499), , pp 334–339. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROMAN.2000.892519

Pan MKXJ, Knoop E, Bacher M, Niemeyer G (2019) Fast handovers with a robot character: small sensorimotor delays improve perceived qualities In: 2019 IEEE/RSJ international conference on intelligent robots and systems, IROS 2019, November 3, 2019–November 8, 2019, Macau, China, pp 6735–6741. https://doi.org/10.1109/IROS40897.2019.8967614

Pradhan A, Findlater L, Lazar A (2019) Phantom friend’ or ‘just a box with information’: personification and ontological categorization of smart speaker-based voice assistants by older adults. In: Proc ACM hum-comput interact, vol 3, no. CSCW. https://doi.org/10.1145/3359316

Salem M, Ziadee M, Sakr M (2014) Marhaba, how may I help you? Effects of politeness and culture on robot acceptance and anthropomorphization. In: 9th Annual ACM/IEEE international conference on human-robot interaction, HRI 2014, March 3, 2014–March 6, 2014, Bielefeld, Germany, pp 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1145/2559636.2559683

Salem M, Eyssel F, Rohlfing K, Kopp S, Joublin F (2013) To err is human (-like): effects of robot gesture on perceived anthropomorphism and likability. Int J Soc Robot 5(3):313–323

Sato D, Sasagawa M, Niijima A (2020) Affective touch robots with changing textures and movements. In: 29th IEEE international conference on robot and human interactive communication, RO-MAN 2020, August 31, 2020–September 4, 2020, Virtual, Naples, Italy, pp 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/RO-MAN47096.2020.9223481

Saunders R, Gemeinboeck P (2018) Performative body mapping for designing expressive robots. In: 9th International Conference on Computational Creativity, ICCC 2018, June 25, 2018–June 29, 2018, Salamanca, Spain, 2018, pp 280–287

Scheunemann MM, Cuijpers RH, Salge C (2020) Warmth and competence to predict human preference of robot behavior in physical human-robot interaction. In: 29th IEEE international conference on robot and human interactive communication, RO-MAN 2020, August 31, 2020–September 4, 2020, Virtual, Naples, Italy, 2020, pp 1340–1347. https://doi.org/10.1109/RO-MAN47096.2020.9223478

Sirkin D, Mok B, Yang S, Ju W (2015) Mechanical ottoman: how robotic furniture offers and withdraws support. In: 10th annual ACM/IEEE international conference on human-robot interaction, HRI 2015, March 2, 2015–March 5, 2015, Portland, OR, United states, 2015, vol 2015-March, pp 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1145/2696454.2696461

Spatola N (2020) Would you turn off a robot because it confronts you with your own mortality?. In: 15th Annual ACM/IEEE international conference on human robot interaction, HRI 2020, March 23, 2020—March 26, 2020, Cambridge, United kingdom, 2020, pp 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1145/3371382.3380736

Spatola N et al (2019) Improved cognitive control in presence of anthropomorphized robots. Int J Soc Robot 11(3):463–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-018-00511-w

Spatola N, Monceau S, Ferrand L (2020) Cognitive impact of social robots: how anthropomorphism boosts performance. IEEE Robot Autom Mag 27(3):73–83

Syrdal DS, Dautenhahn K, Walters ML, Koay KL (2008) Sharing spaces with robots in a home scenario—anthropomorphic attributions and their effect on proxemic expectations and evaluations in a live HRI trial. In: 2008 AAAI Fall Symposium, November 7, 2008–November 9, 2008, Arlington, VA, United states, vol FS-08–02, pp 116–123

Tan H et al (2020) Relationship between social robot proactive behavior and the human perception of anthropomorphic attributes. Adv Robot 34(20):1324–1336. https://doi.org/10.1080/01691864.2020.1831699

Ueno A, Hayashi K, Mizuuchi I (2019) Impression change on nonverbal non-humanoid robot by interaction with humanoid robot. In: 28th IEEE international conference on robot and human interactive communication, RO-MAN 2019, October 14, 2019–October 18, 2019, New Delhi, India. https://doi.org/10.1109/RO-MAN46459.2019.8956240

Vigni F, Knoop E, Prattichizzo D, Malvezzi M (2019) The Role of Closed-Loop Hand Control in Handshaking Interactions. IEEE Robot Autom Lett 4(2):878–885. https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2019.2893402

Wallkötter S, Stower R, Kappas A, Castellano G (2020) A robot by any other frame: framing and behaviour influence mind perception in virtual but not real-world environments. In: Proceedings of the 2020 ACM/ieee international conference on human-robot interaction, New York, NY, USA, pp 609–618. https://doi.org/10.1145/3319502.3374800

Wang Y, Guimbretière F, Green KE (2020) Are space-making robots, agents? Investigations on user perception of an embedded robotic surface. In: 2020 29th IEEE international conference on robot and human interactive communication (RO-MAN), pp 1230–1235

Zanatto D, Patacchiola M, Cangelosi A, Goslin J (2020) Generalisation of anthropomorphic stereotype. int J Soc Robot 12(1):163–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-019-00549-4