Abstract

Socially assistive robots are being developed and tested to support social interactions and assist with healthcare needs, including in the context of dementia. These technologies bring their share of situations where moral values and principles can be profoundly questioned. Several aspects of these robots affect human relationships and social behavior, i.e., fundamental aspects of human existence and human flourishing. However, the impact of socially assistive robots on human flourishing is not yet well understood in the current state of the literature. We undertook a scoping review to study the literature on human flourishing as it relates to health uses of socially assistive robots. Searches were conducted between March and July 2021 on the following databases: Ovid MEDLINE, PubMed and PsycINFO. Twenty-eight articles were found and analyzed. Results show that no formal evaluation of the impact of socially assistive robots on human flourishing in the context of dementia in any of the articles retained for the literature review although several articles touched on at least one dimension of human flourishing and other related concepts. We submit that participatory methods to evaluate the impact of socially assistive robots on human flourishing could open research to other values at stake, particularly those prioritized by people with dementia which we have less evidence about. Such participatory approaches to human flourishing are congruent with empowerment theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Socially assistive robots are being developed and tested to support social interactions and assist with healthcare needs (See Box below for more details on socially assistive robots). These robots could play a variety of roles such as “(a) changing how the person is perceived, (b) enhancing the social behavior of the person, (c) modifying the social behavior of others, (d) providing structure for interactions, and (e) changing how the person feels” [1]. Clinical tools based on artificial intelligence (AI) such as some socially assistive robots made available to patients with dementia have many proven and possible benefits such as providing help with the accomplishment of daily tasks [2] and support for social relations and communication [3]. In a horizon of 5, 10 and 15 years, it is possible to think that this type of technology will be able to significantly support people suffering from neurodegenerative diseases, especially diseases that lead to losses of cognitive and communicational functions [4, 5]. These technologies bring their share of situations where questions regarding key aspects of human wellbeing such as relationships and autonomy are raised. For example, does a robot that talks and interacts with a dementia patient represent an inauthentic relationship based on lying? Can the delegation of dementia management to the robot create a form of social isolation of the person with dementia by reducing human contact with caregivers and family members? Thus, important ethical issues need to be addressed for a responsible development of the use of socially assistive robots in the field of health, including their impact on human flourishing (aka eudaimonia)—a concept that refers to the overall existential well-being of individuals and is highly correlated with both physical and psychological health [6].

The impact of socially assistive robots on human flourishing is not yet well understood in the current state of the literature. Several aspects of these robots affect human relationships and social behavior, i.e., fundamental aspects of human existence. Moreover, the concept of human flourishing emphasizes that living with dementia can be part of a life trajectory and generate meaning for the person and those around them [7]. Without denying the challenges created by this condition, this concept reflects an orientation towards self-actualization and respect of the person with dementia. However, the concept of flourishing can easily become normative, narrow, and directive based on specific understandings of flourishing [8, 9]. Thus, this concept should be envisioned openly in order to understand what represents the interest and preferences of a person with dementia. In fact, this concept may at first appear paradoxical in the context of dementia, a condition which is reputed to take away personhood and notably, the thoughts and memories that people with dementia have about themselves and about their loved ones. There are also behavioral changes in dementia, which can drastically change people [10, 11]. Unsurprisingly, the degenerative aspects of dementia can encourage breaches of respect for people through fear, stigma and discrimination [12, 13]. However, applying the lens of human flourishing to the context of dementia joins several other clinical approaches to improve care for people with dementia, namely those that promote the recognition of personhood in dementia [14,15,16]. In particular, the use of participatory methods [14, 17,18,19] to understand the impact of technologies such as socially assistive robots on human flourishing could be an avenue to explore, in order to expand understandings of human flourishing beyond current theories and scales in persons not suffering from dementia. It is increasingly clear that participatory methods are: (1) useful to develop an open and constructive concept of human flourishing [17] and (2) have proven their validity elsewhere in other contexts such as research on social participation [20]. However, the current state of knowledge suggests significant gaps in our knowledge of the state of relevant research.

Accordingly, this paper has two objectives:

Undertake a scoping review to study the literature on human flourishing as it relates to health uses of socially assistive robots to (1) determine whether methods of assessing the impact of socially assistive robots on human flourishing exist in this context and (2) critically assess their strengths and weaknesses.

And, pending studies examining human flourishing or some of its dimensions:

Critically discuss these findings to assess the relevance of using participatory and deliberative methods to address human flourishing in the context of the use of socially assistive robots in dementia based on (1) general literature on human flourishing in the context of new technology, as well as (2) participatory methods to evaluate the impact of socially assistive robots on human flourishing.

2 Methodology

We undertook a scoping review [33, 34] to study the literature on human flourishing as it relates to health uses of AI with a focus socially assistive robots in the context of dementia. We used an integrative theoretical framework on human flourishing developed by Ryff and Singer [35] to evaluate and assess the literature following the process established by Lanteigne et al. [17]. We also enriched and adapted this framework to seize other considerations that the addressed well-being and flourishing of people with dementia.

2.1 Review Question

Initially, this literature review aimed to (1) ascertain whether methods of assessing the impact of socially assistive robots on human flourishing exist and (2) assess them critically for their strengths and weaknesses with an eye to the eventual value of participatory methods to promote human flourishing. To narrow down the scope of the project and find a suitable clinical context of investigation, several searches were done on different databases to determine what kinds of AI technology exist in healthcare and in which contexts they are used. Subsequently, a decision was made by the authors to focus on socially assistive robots in the context of dementia because of the relevance of socially assistive robots in this clinical context and our ability to broker collaborations to build on this topic. Indeed, given the orientation of this project, we constituted an advisory committee composed of caregivers of persons with dementia and experts in biomedical engineering, ethics, and geriatrics. This advisory committee met twice to provide input on (1) the initial design and orientation of the scoping review and (2) the penultimate version of the manuscript, including advanced background, methods, results and draft discussion points.

2.2 Article Search

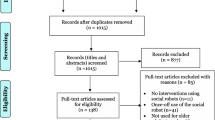

We conducted our search between March and July 2021 on the following databases: Ovid MEDLINE, PubMed and PsycINFO. Search terms were developed in consultation with a research librarian from Université de Montréal to generate an inclusive initial list of references using very general keywords and keyword combinations: 1- Robotics. 2- Psychology.fs. OR pets/OR animals/OR friends. 3- 1 and 2. 4- AIBO.mp. 5- OR/3–4. 6- Exp Dementia. 7- dement* or Alzheimer*.mp. 8- 6 OR 7. 9- 5 AND 8 (for a total of 68 hits as a result). We used the following keywords on Ovid MEDLINE: ((robotics/AND (psychology.fs OR pets/OR animals/OR friends/)) OR AIBO.mp) AND (Exp dementia/OR (dement* OR Alzheimer*.mp). Since “socially assistive robot” does not constitute an established MeSH keyword, we also searched PubMed and PsycINFO with socially assistive robots + dementia. Using human flourishing as a keyword would have yielded no relevant articles but that would have been an unfair result since many papers discuss important dimensions of flourishing such as autonomy and positive relationships with others. Accordingly, we searched for all relevant publications on socially assistive robots in the context of dementia as described above and manually screened through them to find and extract content relevant to human flourishing. Our searches yielded 109 articles which we imported into Covidence.org. After eliminating duplicates (n = 18), there were 91 articles remaining. These were screened by one member of the team (EF). An initial screening was done based on the relevance of titles and abstracts using the inclusion and exclusion criteria specified below. This yielded a total of 61 articles for the next step. After screening for full-text appraisal, we ended up with 28 articles to include in the review. See Fig. 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram.

2.3 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included, articles had to (1) be published in English or French, (2) concern socially assistive robots, (3) discuss a socially assistive technology involving AI since this is partly the focus of this review (see Box 1), (4) in the context of dementia. We focused our data extraction on qualitative studies because most quantitative studies did not report meaningful data that addressed human flourishing. This yielded a fifth criterion: (5) feature qualitative results. We further excluded opinion papers, open letters, research notes and case reviews.

2.4 Data Extraction

Each article was analyzed to extract the following information: (1) author and affiliations, (2) type of socially assistive technology, (3) objectives of the study, (4) study design, (5) methods, (6) content related to human flourishing, (7) participatory nature of the study, (8) sample size, (9) context of the study, (10) main outcomes, (11) main conclusions, and (12) main limitations of the study. Items 1–5 and 7–12 were mainly extracted based on the abstract and complemented with consultation of the full manuscript when needed; items 6 and 7 which are central to this review were extracted based on the analysis of the manuscript. In the tables, content is pasted from original papers with little or very minor changes.

2.5 Data Synthesis

Descriptive statistics for simple categories (items 1–5 and 7–12 above) were synthesized in text and tables. Then, we analyzed all the articles to see if there was information relating to human flourishing (item 6), whether falling directly into one of Ryff’s categories (the six dimensions) or pertaining to these dimensions or the concept of human flourishing indirectly and in a larger sense. Components did not have to be explicitly mentioned as a dimension of human flourishing, as we used Ryff and Singer’s framework more liberally considering that no articles used this theory directly. See Table 1 for indications about human flourishing. To standardize the writing and emphasize the role of people with dementia, we have standardized the description of users of socially assistive robots as users or people with dementia (as person-first language) but the terms participants, subjects, and patients were often used.

3 Results

3.1 Basic Sample Characteristics

Our searches yielded 28 papers published from 2013 to 2019. Studies were mostly from Western European countries [United Kingdom (3), France (2), Norway (1), Sweden (1), Ireland (1), Spain (1), Italy (2), Switzerland (2), Austria (1)], as well as from North America [Canada (3), USA (3), Mexico (1)] and Oceania [Australia (5), New Zealand (2)] (see Table 2). Different socially assistive robots were investigated, the most frequent being PARO, a plush seal [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. Other robots studied were MARIO [46], NAO [47] and JustoCat [48] (See Table 2). These robots are conceived specifically to therapeutically assist users by enhancing their social abilities and be of service in their day-to-day activities. Some, like NAO and MARIO, have more humanoid characteristics, while others are meant to look like animals (PARO and JustoCat).

3.2 General Content of the Sample

The final sample featured systematic literature reviews (8), qualitative studies (5), qualitative design of cluster-randomized controlled trials (4), pilot studies (4), observational studies (3), experimental protocol/studies (2), scoping reviews (1) and mixed-method approaches (1) (See Table 2). The literature reviews centered on examining, assessing, and discussing previous research on socially assistive robots and intelligent assistive technologies in the context of dementia. Central themes discussed in these reviews were the perceived usefulness of socially assistive robots [49]; ethical issues associated with their use [50, 51] (see also Sect. 3.3.8. below); their potential contribution to care [38, 40, 44, 47, 52, 53]; various cautions regarding their use [52]; and their strengths, weaknesses, as well as opportunities for improvement in future research and practice [53]. As for the trials and the observational, pilot, and experimental studies, the objective was most often to get perspectives, levels of acceptance, and opinions on the socially assistive robots investigated from people with dementia, their caregivers, nurses, and families. There was no participatory study design, although several articles addressed the perceptions and experiences of participants through qualitative methods [42,43,44,45, 48, 54, 55]. The outcomes reported for various socially assistive robots were mostly positive. Results typically showed that socially assistive robots can improve mood, social engagement, and communication, while reducing agitation, medical dosage, and negative emotions [39, 41, 44,45,46,47,48,49, 52, 55,56,57]. Users were generally willing to adopt the technology, with the consideration that users’ needs and interests should be taken into account when implementing the technology. Unfavorable outcomes included the possibility of losing contact with other humans and being deceived or infantilized by the technology. Limits reported by researchers were most often small sample sizes, lack of generalizability, and challenges in obtaining consent (because of loss of cognitive functions).

3.3 Dimensions of Human Flourishing

Twenty-eight articles touched upon at least one element pertaining to human flourishing according to Ryff and Singer’s framework (see Table 3).

3.3.1 Positive Relationship with Others

This was the dimension of human flourishing most often evoked in the sample. Half of the articles emphasized that socially assistive robots are a source of companionship and engagement, while reducing loneliness [41,42,43, 45,46,47,48,49, 52, 53, 58, 59]. Such benefits are amongst the main purposes of socially assistive robots, as it is supposed to bring a sense of community while helping the user practice and develop social skills they can apply to their human interactions. For example, interacting with robopets induced verbal responses, leading to users to talk more either to the robopets or with other people. Some users even considered the robot to be a friend, not just a robot or an assistive device [58]. The technology brought opportunities for communication with the robot itself [39, 44, 46, 56, 57] but also facilitated and promoted communication with others [38, 54, 60]. Conversing with the robot not only made people smile and laugh but also increased their openness to talk and interact with the robot and/or people around them [56]. One study indicated an improvement in human contact and empathy through the use of the robot [51].

3.3.2 Environmental Mastery

A total of fifteen studies considered matters consistent with environmental mastery. Many of the studies mentioning content related to this dimension focused on how the robot brings safety and comfort to the user [42, 48,49,50,51, 54, 55, 61, 62]. This was accomplished in various ways, mostly by helping users navigate their surroundings more easily and providing a trustworthy source of help for users. For example, socially assistive robots can promote risk prevention and provide a certain level of care through components such as fall detection and management of critical situations [42, 46, 48,49,50, 54, 61]. They can also support everyday tasks like online grocery shopping, journey planning, or simplified internet access, increasing control of the user’s own surroundings [54]. Additionally, socially assistive robots can enhance protection from or reduce the likelihood of danger or injury [50], augmenting the user’s ability to care for themselves [49]. Socially assistive robots were also described as giving their user more control over their life [39]. One concern related to mastering one’s environment is the affordability of the technology [38, 50, 61]: families, nurses, and other people surrounding the person with dementia brought up the need for the technology to be financially accessible for people with less income. Other worries like protection of vulnerability and invasiveness [36, 50] and the consideration that a robot can be a source of overstimulation [58] were taken to be important in development of such technology, as the robot operates in proximity with the person with dementia.

3.3.3 Personal Growth

Matters related to the dimension of personal growth were present in fifteen studies. Different studies reported that interacting with the robot could result in changes in well-being or mental health by alleviating symptoms of dementia [36, 37, 45, 48, 53]. This led to a reduction in depressive symptoms and improvements of cognitive functioning [41, 58]. Decreases in negative behavioral states were also evaluated and observed with respect to anxiety, sadness, yelling behavior, isolative behavior, reports of pain, and wandering/pacing behavior [41, 47]. Moreover, socially assistive robots fostered personal growth insofar as they can improve the user’s expressions of pleasure and have some effect in reducing agitation [43]. People with dementia could then be perceived as having higher emotional intelligence [46]. One of the concerns that pertains to this category is how bringing a robot that looks like a plush toy could lend to feelings of infantilization for residents [52, 58]. Such infantilization could reinforce perceptions from others that could hurt or discourage personal growth and, more generally, infantilization runs counter to the notion of personal growth and development.

3.3.4 Autonomy

Twelve studies assessed the autonomy of persons with dementia. Most studies mentioned how the robot could help with daily activities and maintaining independence as long as possible, as it assists the user in completing different tasks like eating, drinking, and cooking, as well as by reminding them of appointments [37, 39, 42, 49,50,51, 61, 62]. Maintaining independence can be achieved through the assistive aspect of the robot, helping the person with dementia go through their day, reminding them how to do regular daily tasks. It can be perceived as “helping people to help themselves” [55]. Other concepts like upholding freedom of choice for the user [44] or consent and privacy [51] were reported, since the technology can contribute to having users’ rights upheld and respected by facilitating the person with dementia to make their own choices [44]. Autonomy was also considered a core attribute of quality of care [46] to which socially assistive robots can contribute.

3.3.5 Purpose in Life

A small number of articles (6/28) evaluated the impact of socially assistive robots on issues related to purpose in life. Researchers indicated that the robot can be something to care of and to look forward to [42, 45]. It also gave users a sense of responsibility [43]. Other articles also explored how the robot can facilitate various meaningful leisure pursuits [61], which emphasizes the stated importance of having access to stimulating activities adapted to the person with dementia [54].

3.3.6 Self-Acceptance

Only three studies reported outcomes related to the dimension of self-acceptance. Two of them exemplified how the robot builds up users’ confidence, specifically confidence to talk to other people, as it helps them practice and develop social skills [42, 58]. Socially assistive robots were perceived as being non-critical and helped users forget their dementia, which made them feel more confident and supported [46].

3.3.7 Other Aspects of Human Flourishing

As announced in the methods, certain components relating to human flourishing in a larger sense provided alternative lenses to the six dimensions proposed by Ryff and Singer. Quality of life is a concept that was used to capture aspects such as positive emotions, physical comfort, happiness and enjoying relationships with others, which were mentioned in eight articles. Quality of life was even considered “an appropriate indicator for assessing the effects of PARO interventions” [40], p. 212. For instance, it was found that socially assistive robots had the ability to reduce agitated behavior [42] and bring forward positive emotions [39]. Increasing symptom management [38, 48, 53] was another common lens brought up in 14 articles. For example, people with dementia using the robot PARO benefited from taking less medication related to their agitative state and cognitive disfunctions [38,39,40, 48], as interventions with the robot improved their general mood state [42]. It also led to reduced anxiety [49], induced a state of calm [43], and reduced stress [36]. Furthermore, users and their families considered the robot easy to use [48], which helped in monitoring the health and well-being of the person with dementia [49] and maintaining their independent living [39].

3.3.8 Challenges of Socially Assistive Robots Posed to Human Flourishing

Seven articles mentioned more negative effects of robot implementation like deception, since it is not an actual living being but is meant to look like one [45, 52]. Pu et al. [45] argued that benefits of the robot could outweigh this risk. Other risks include the possibility of being ridiculed for interacting with a device as if it were a living animal or human [48] or the probability of infantilizing or dehumanizing the user [38, 59]. Certain negative aspects were more sporadically discussed, such as overstimulation, caring too much for the robot, and the reminiscence of a dead animal from the past [48, 59]. Three articles mentioned that interactions with the robot should not be envisioned in a “one size fits all” manner [40, 42, 50]. Personal intervention benefits the person with dementia as it helps them fulfill their wishes and empowers them [50]. For example, an important factor is making sure group size and intervention type in research are based on user needs, because of “their possible impact on outcome” [40], p. 213. Other related issues include the importance of considering robot acceptance by the user with criteria like effort expectancy (ease of use), perceived trust (security of data), facilitating conditions (organizational and technological supports for users), technology anxiety (apprehension about use), performance expectancy (perceived benefit of use), social influence (positive opinions of others about technology), and perceived cost [61]. Articles discussing the importance of personalized care were premised on the initial step of making sure the interventions are oriented towards the wants and needs of the person with dementia, and verifying whether the user is interested in using the technology in the first place [36, 61].

4 Discussion

The purpose of our project was to undertake a scoping review to study the literature on human flourishing related to the use of socially assistive robots in the context of dementia to (first objective): (1) determine whether methods of assessing the impact of socially assistive robots on human flourishing exist in this context and (2) critically assess their strengths and weaknesses. As a second objective, we also wanted to discuss these findings to assess the relevance of using participatory and deliberative methods to address human flourishing in the context of the use of socially assistive robots in dementia based on (1) general literature on human flourishing in the context of new technology, as well as (2) participatory methods to evaluate the impact of socially assistive robots on human flourishing

Regarding our first objective, the results showed that there was no formal evaluation of the impact of socially assistive robots on human flourishing in the context of dementia in any of the 28 articles selected for the literature review. Although several articles touched on at least one dimension of human flourishing and other related concepts, to our knowledge, no formal investigation of the positive or negative impacts of socially assistive robots on human flourishing has been undertaken, i.e., an investigation using explicitly a scale or the concept of human flourishing such as Ryff’s account of human flourishing. Moreover, a common human flourishing scale to evaluate human flourishing was not used (e.g., the Psychological Wellbeing Scale [63], the Flourish measure [64]) although quality of life was assessed in some studies [65,66,67]. This could suggest that the broader existential meaningfulness of the technology within the person’s life narrative is overseen beyond more clinically-oriented quality of life measures. Indeed, our analysis of outcome measures suggests that the gaze is predominantly clinical with more limited attention to what actually counts for the person. These observations are supported by a scoping review of instruments developed to assess well-being in people with dementia [68]. Of the 19 instruments identified in this review, none were used to evaluate socially assistive robots. Another recent study on the analysis of two AI-based systems for clinical decision support (Painchek® and IDx-DR) reveals the need for studies to properly establish the link between AI and human flourishing. Paincheck was developed to improve the quality of pain management in non-verbal people, such as those with severe dementia. IDx-DR is an AI-based system for automatic detection of early signs of eye disease in diabetic patients. Both technological applications could be limited by user and public involvement in the development and deployment of AI and socially assistive robots in healthcare and the attention to their impact on relationships in healthcare [69]. The limited attention to the impact of socially assistive robots on the person as a person could be caused by the fact that personhood is seemingly lost in dementia. Thus, flourishing may not be the frame of reference used or considered relevant as often as, for example, quality of life or quality of care, which can be brought to more objective clinical guideposts [70].

Despite the lack of formal use of the concept of human flourishing and of scales measuring it, specific dimensions of human flourishing were commonly tackled, sometimes more implicitly framed under the guise of quality of life. For example, our review shows that articles often touched upon positive relationships with others (25/28), followed by environmental mastery (15/28) and personal growth (15/28), then on autonomy (12/28). Purpose in life (6/28) and self-acceptance (3/28) were less often referenced. This suggests that socially assistive robots are seen as a connector to society insofar as they allow for a perceived social presence and promotion of social connectivity [71]. The impact of this technology on positive relationships can also be seen in children who, with the use of technology, surmount anxiogenic situations or even manage to create networks of friends [72]. Through positive relationships with others, people with dementia can thrive with the support of loved ones who can help them hold onto valued memories [73]. These results help explain our findings that identify positive relationships with others as well as environmental mastery as the dimensions that the articles focus on most. VanderWeele [64] has shown how human flourishing is present in family, work, education, and community, i.e., where the construction of positive relationships take place. Additionally, in older adults, the integration of health technologies can facilitate for the user significant relationships, rewarding activities, spirituality, and physical activity within specific sociocultural contexts [74]. These areas showing the importance of participation and engagement in social activities promote the idea that there is an opportunity to explore participatory methods of understanding and enacting human flourishing in the context of dementia and socially assistive robots.

The discussion around specific dimensions of flourishing (e.g., autonomy, positive relationships with others) certainly represents part of the concerns in the ethics literature, even if seldom framed as such, i.e., as flourishing explicitly. This may be caused by the fact that flourishing might not be the most common frame of reference to evaluate people with dementia and their personhood, but rather quality of life or of care, and more specific concerns related to the impact of socially assistive robots on personal relationships. Despite these limitations, the angle of human flourishing is one which invites further thinking about existential meaning in the context of dementia. It also corresponds to the small but growing literature on flourishing in dementia [66], especially in the context of the use of art-based interventions/therapies such as dance and music [65, 67, 75] and in cultures where the ageing person is valued based on traditions and customs [76]. There are clear clinical and moral implications of the attitude towards people with dementia as persons [15], which could warrant greater attention in the context of the development of technologies intended to facilitate the social life and social interactions of the person with dementia. This is partly the goal of “dignity therapy” in the context of elderly care and dementia [77].

Even if it is not extensively investigated at this point in time, the concept of human flourishing offers an interesting lens through which to understand the person with dementia. However, human flourishing can appear as a boiler plate concept with limited connections to real lived experiences [17]. But could participatory methods support the study and development of human flourishing in people with dementia? Although there are no specific studies on participatory methods on the impact of socially assistive robots on human flourishing in dementia, it is understandable why the articles in our study focus more on certain dimensions such as positive relationships with others, environmental control, personal growth, and autonomy. Nonetheless, participatory approaches to human flourishing are congruent with empowerment theory and interventions [78]; they aim to expand and nurture capabilities [20]. In a semi-participatory study on the impact of the use of robots on clients and care staff in institutions dedicated to older adults, a motivation of older adults to learn was noted, as well as the fact that robots promoted interaction and exercise [79]. Participatory approaches to human flourishing could help explore the possibility of using ethics concepts and theory to further enriching human experiences [17, 80]. However, even if participatory methods are promising when older people are involved, one must be careful that problems related to the respect of their confidentiality be monitored when participating in interventions, based on the implementation of technologies [81]. For successful participation in projects involving people with dementia, importance must be placed on how to obtain consent or inform them of the project, due to their possible memory loss [82]. It is also worth noting that participatory methods can help situate health (in a more biomedical sense) within a more holistic understanding of well-being. Health is not the only element of well-being or the only value sought by people with dementia [83]. Socially assistive robot use in healthcare needs to take this into account to avoid reductionism that demonstrates paternalism, towards people with dementia. Participatory methods to evaluate the impact of socially assistive robots on human flourishing could open research to other values at stake, particularly those prioritized by people with dementia, about which we have less information. Hence, there is an opportunity to explore participatory methods of understanding and enacting human flourishing in the context of dementia and socially assistive robots.

5 Conclusion

This review set out to survey the literature to understand whether human flourishing—and some of its key dimensions—were considered in investigations and discussions of the impact of socially assistive robots in the context of dementia. Although no formal measure or study of human flourishing has yet been undertaken in this context, specific dimensions of human flourishing were often addressed, such as the impact of socially assistive robots on meaningful and positive human relationships. However, the absence of an integrated existential lens such as human flourishing to capture what is meaningful to the person with dementia may reflect the assumption that people with dementia lose personhood in the course of their illness. Given the possibility that commonly used scales for human flourishing may be ill-adapted to grasp the impact of technology on people with dementia, we suggest that potentially more open-ended investigation (e.g., using participatory and qualitative) approaches could be in order.

References

Chita-Tegmark M, Scheutz M (2021) Assistive robots for the social management of health: a framework for robot design and human–robot interaction research. Int J Soc Robot 13:197–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-020-00634-z

Briggs P, Scheutz M, Tickle-Degnen L (2015) Are robots ready for administering health status surveys? First results from an HRI study with subjects with Parkinson’s disease. In: 2015 10th ACM/IEEE international conference on human-robot interaction (HRI), pp 327–334

Savage N (2022) Robots rise to meet the challenge of caring for old people. Nature 601(7893):S8–S10. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-00072-z

Onyeulo EB, Gandhi V (2020) What makes a social robot good at interacting with humans? Information 11:43. https://doi.org/10.3390/info11010043

Shibata T, Wada K (2011) Robot therapy: a new approach for mental healthcare of the elderly—a mini-review. Gerontology 57:378–386. https://doi.org/10.1159/000319015

Ryff CD (2014) Psychological well-being revisited: advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychother Psychosom 83(1):10–28. https://doi.org/10.1159/000353263

Garcia L, Drummond N, McCleary L (2020) Steering through the waves and adjusting to transitions in dementia. In: Garcia LJ, McCleary L, Drummond N (eds) Evidence-informed approaches for managing dementia transitions: riding the waves. Academic Press, Cambridge, MA, pp 235–256

Misselbrook D (2015) Virtue ethics—an old answer to a new dilemma? Part 1. Problems with contemporary medical ethics. J R Soc Med 108(2):53–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076814563367

Terzis GN (1994) Human flourishings: a psychological critique of virtue ethics. Am Philos Q 31(4):333–342

Campbell N, Maidment ID, Randle E et al (2020) Preparing care home staff to manage challenging behaviours among residents living with dementia: a mixed-methods evaluation. Health Psychol Open 7:205510292093306

Rankin KP, Baldwin E, Pace-Savitsky C et al (2005) Self awareness and personality change in dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76:632–639. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2004.042879

Low LF, Purwaningrum F (2020) Negative stereotypes, fear and social distance: a systematic review of depictions of dementia in popular culture in the context of stigma. BMC Geriatr 20:477. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01754-x

Riley RJ, Burgener S, Buckwalter KC (2014) Anxiety and stigma in dementia: a threat to aging in place. Nurs Clin North Am 49(2):213–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnur.2014.02.008

Blain-Moraes S, Racine E, Mashour GA (2018) Consciousness and personhood in medical care. Front Hum Neurosci 12:306. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00306

Hunter PV, Hadjistavropoulos T, Smythe WE et al (2013) The personhood in dementia questionnaire (PDQ): establishing an association between beliefs about personhood and health providers’ approaches to person-centred care. J Aging Stud 27:276–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2013.05.003

Walsh S, O’Shea E, Pierse T et al (2020) Public preferences for home care services for people with dementia: a discrete choice experiment on personhood. Soc Sci Med 245:112675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112675

Lanteigne A, Genest M, Racine E (2021) The evaluation of pediatric-adult transition programs: what place for human flourishing? SSM Ment Health 1:100007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100007

Sample M, Aunos M, Blain-Moraes S et al (2019) Brain-computer interfaces and personhood: interdisciplinary deliberations on neural technology. J Neural Eng 16:063001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/ab39cd

Willen SS (2022) Flourishing and health in critical perspective: an invitation to interdisciplinary dialogue. SSM Ment Health 2:100045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100045

Clark DA, Biggeri M, Frediani AA (2019) The capability approach, empowerment and participation: concepts, methods and applications. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Bedaf S, Gelderblom GJ, De Witte L (2015) Overview and categorization of robots supporting independent living of elderly people: what activities do they support and how far have they developed. Assist Technol 27(2):88–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.2014.978916

van der Putte D, Boumans R, Neerincx M et al (2019) A social robot for autonomous health data acquisition among hospitalized patients: an exploratory field study. In: 2019 14th ACM/IEEE international conference on human-robot interaction (HRI), pp 658–659

Wilson JR, Tickle-Degnen L, Scheutz M (2016) Designing a social robot to assist in medication sorting. In: Proceedings of the 8th international conference on social robotics, Nov 1–3; Kansas City, MO, pp 211–221

Kim GH, Jeon S, Im K et al (2013) Structural brain changes after robot-assisted cognitive training in the elderly: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Alzheimers Dement 9:P476–P477. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0123251

Banks MR, Willoughby LM, Banks WA (2008) Animal-assisted therapy and loneliness in nursing homes: use of robotic versus living dogs. J Am Med Dir Assoc 9(3):173–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2007.11.007

Takayanagi K, Kirita T, Shibata T (2014) Comparison of verbal and emotional responses of elderly people with mild/moderate dementia and those with severe dementia in responses to seal robot. PARO Front Aging Neurosci 6:257. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2014.00257

Arkin RC, Scheutz M, Tickle-Degnen L (2014) Preserving dignity in patient caregiver relationships using moral emotions and robots. In: 2014 IEEE international symposium on ethics in science, technology and engineering, IEEE 2014, pp 1-5

Wada K, Shibata T (2007) Social effects of robot therapy in a care house - change of social network of the residents for two months. In: Proceedings 2007 IEEE international conference on robotics and automation, pp 1250–1255

Łukasik S, Tobis S, Kropińska S et al (2020) Role of assistive robots in the care of older people: survey study among medical and nursing students. J Med Internet Res 22:e18003. https://doi.org/10.2196/18003

Wada K, Ikeda Y, Inoue K et al (2010) Development and preliminary evaluation of a caregiver's manual for robot therapy using the therapeutic seal robot Paro. In: 19th International symposium in robot and human interactive communication IEEE 2010, pp 533–538

Zhao S (2006) Humanoid social robots as a medium of communication. New Media Soc 8(3):401–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444806061951

Wiederhold BK (2021) The ascent of social robots. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 24(5):289–290. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2021.29213.editorial

Arksey H, O’Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 8:19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK (2010) Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 5(1):69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Ryff CD, Singer BH (2008) Know thyself and become what you are: a eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. J Happiness Stud 9:13–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9019-0

Demange M, Lenoir H, Pino M et al (2018) Improving well-being in patients with major neurodegenerative disorders: differential efficacy of brief social robot-based intervention for 3 neuropsychiatric profiles. Clin Interv Aging 13:1303–1311. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S152561

Góngora Alonso S, Hamrioui S, de la Torre DI et al (2019) Social robots for people with aging and dementia: a systematic review of literature. Telemed J e-Health 25:533–540. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2018.0051

Hung L, Liu C, Woldum E et al (2019) The benefits of and barriers to using a social robot PARO in care settings: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr 19:232. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1244-6

Jøranson N, Pedersen I, Rokstad AMM et al (2016) Change in quality of life in older people with dementia participating in Paro-activity: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs 72:3020–3033. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13076

Kang HS, Makimoto K, Konno R et al (2020) Review of outcome measures in PARO robot intervention studies for dementia care. Geriatr Nurs 41:207–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2019.09.003

Lane GW, Noronha D, Rivera A et al (2016) Effectiveness of a social robot, “Paro,” in a VA long-term care setting. Psychol Serv 13:292–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000080

Moyle W, Bramble M, Jones C et al (2018) Care staff perceptions of a social robot called Paro and a look-alike plush toy: a descriptive qualitative approach. Aging Ment Health 22:330–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1262820

Moyle W, Bramble M, Jones CJ et al (2019) “She had a smile on her face as wide as the great Australian bite”: a qualitative examination of family perceptions of a therapeutic robot and a plush toy. Gerontologist 59:177–185. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx180

Moyle W, Jones C, Murfield J et al (2019) Using a therapeutic companion robot for dementia symptoms in long-term care: reflections from a cluster-RCT. Aging Ment Health 23:329–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1421617

Pu L, Moyle W, Jones C (2020) How people with dementia perceive a therapeutic robot called PARO in relation to their pain and mood: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs 29(3–4):437–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15104

Casey D, Barrett E, Kovacic T et al (2020) The perceptions of people with dementia and key stakeholders regarding the use and impact of the social robot MARIO. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:8621. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228621

Robaczewski A, Bouchard J, Bouchard K et al (2021) Socially assistive robots: the specific case of the NAO. Int J Soc Robot 13:795–831

Gustafsson C, Svanberg C, Müllersdorf M (2015) Using a robotic cat in dementia care: a pilot study. J Gerontol Nurs 41(10):46–56. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20150806-44

Law M, Sutherland C, Ahn HS et al (2019) Developing assistive robots for people with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia: a qualitative study with older adults and experts in aged care. BMJ Open 9:e031937. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031937

Ienca M, Wangmo T, Jotterand F et al (2018) Ethical design of intelligent assistive technologies for dementia: a descriptive review. Sci Eng Ethics 24:1035–1055. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9976-1

Wangmo T, Lipps M, Kressig RW et al (2019) Ethical concerns with the use of intelligent assistive technology: findings from a qualitative study with professional stakeholders. BMC Med Ethics 20:98. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-019-0437-z

Mordoch E, Osterreicher A, Guse L et al (2013) Use of social commitment robots in the care of elderly people with dementia: a literature review. Maturitas 74:14–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.10.015

Scoglio AA, Reilly ED, Gorman JA et al (2019) Use of social robots in mental health and well-being research: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 21:e13322. https://doi.org/10.2196/1332254

Pino M, Boulay M, Jouen F et al (2015) “Are we ready for robots that care for us?” Attitudes and opinions of older adults toward socially assistive robots. Front Aging Neurosci 7:141. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2015.00141

Zuschnegg J, Paletta L, Fellner M et al (2021) Humanoid socially assistive robots in dementia care: a qualitative study about expectations of caregivers and dementia trainers. Aging Ment Health 26(6):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1913476

Chu M-T, Khosla R, Khaksar SMS et al (2017) Service innovation through social robot engagement to improve dementia care quality. Assist Technol 29(1):8–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.2016.1171807

Cruz-Sandoval D, Favela J (2019) Incorporating conversational strategies in a social robot to interact with people with dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 47:140–148. https://doi.org/10.1159/000497801

Abbott R, Orr N, McGill P et al (2019) How do “Robopets” impact the health and well-being of residents in care homes? A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Int J Older People Nurs 14(3):e12239. https://doi.org/10.1111/opn.12239

Bradwell HL, Edwards KJ, Winnington R et al (2019) Companion robots for older people: importance of user-centred design demonstrated through observations and focus groups comparing preferences of older people and roboticists in South West England. BMJ Open 9(9):e032468. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032468

Obayashi K, Kodate N, Masuyama S (2020) Measuring the impact of age, gender and dementia on communication-robot interventions in residential care homes. Geriatr Gerontol Int 20(4):373–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13890

Arthanat S, Begum M, Gu T et al (2020) Caregiver perspectives on a smart home-based socially assistive robot for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 15(7):789–798. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2020.1753831

Darragh M, Ahn HS, MacDonald B et al (2017) Homecare robots to improve health and well-being in mild cognitive impairment and early stage dementia: results from a scoping study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 18(12):1099.e1-1099.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.08.019

Ryff CD, Almeida DM, Ayanian JZ et al (2021) Midlife in the United States (MIDUS 2), 2004–2006. Ann-Arbor (MI): inter-university consortium for political and social research [distributor]. https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/NACDA/studies/4652/publications

VanderWeele TJ (2017) On the promotion of human flourishing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114(31):8148–8156. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1702996114

Kontos P, Grigorovich A (2018) Integrating citizenship, embodiment, and relationality: towards a reconceptualization of dance and dementia in long-term care. J Law Med Ethics 46(3):717–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073110518804233

Kontos P, Radnofsky ML, Fehr P et al (2021) Separate and unequal: a time to reimagine dementia. J Alzheimers Dis 80(4):1395–1399. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-210057

Pavlicevic M, Tsiris G, Wood S et al (2015) The ‘ripple effect’: towards researching improvisational music therapy in dementia care homes. Dementia 14(5):659–679. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301213514419

Clarke C, Woods B, Moniz-Cook E et al (2020) Measuring the well-being of people with dementia: a conceptual scoping review. Health Qual Life Outcomes 18:249. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01440-x

Rogers WA, Draper H, Carter SM (2021) Evaluation of artificial intelligence clinical applications: detailed case analyses show value of healthcare ethics approach in identifying patient care issues. Bioethics 35(7):623–633. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12885

Burckhardt CS, Anderson KL (2003) The quality of life scale (QOLS): reliability, validity, and utilization. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1:60. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-60

Christoforakos L, Feicht N, Hinkofer S et al (2021) Connect with me. Exploring influencing factors in a human-technology relationship based on regular chatbot use. Front Digit Health 3:689999. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2021.689999

Wilson S (2016) Digital technologies, children and young people’s relationships and self-care. Child Geogr 14(3):282–294

McFadden SH, McFadden JT (2011) Aging together: dementia, friendship, and flourishing communities. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Von Humboldt S, Mendoza-Ruvalcaba NM, Arias-Merino ED et al (2020) Smart technology and the meaning in life of older adults during the Covid-19 public health emergency period: a cross-cultural qualitative study. Int Rev Psychiatry 32(7–8):713–722

Tamplin J, Clark IN, Lee Y-EC et al (2018) Remini-sing: a feasibility study of therapeutic group singing to support relationship quality and wellbeing for community-dwelling people living with dementia and their family caregivers. Front Med 5:245. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2018.00245

Lau WYT, Stoner C, Wong GH-Y et al (2021) New horizons in understanding the experience of Chinese people living with dementia: a positive psychology approach. Age Ageing 50(5):1493–1498. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afab097

Johnston B, Lawton S, McCaw C et al (2016) Living well with dementia: enhancing dignity and quality of life, using a novel intervention, dignity therapy. Int J Older People Nurs 11(2):107–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/opn.12103

Perkins DD, Zimmerman MA (1995) Empowerment theory, research, and application. Am J Community Psychol 23:569–579

Melkas H, Hennala L, Pekkarinen S et al (2020) Impacts of robot implementation on care personnel and clients in elderly-care institutions. Int J Med Inform 134:104041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.10404180

Racine E, Cascio MA, Montreuil M et al (2019) Instrumentalist analyses of the functions of ethics concept-principles: a proposal for synergetic empirical and conceptual enrichment. Theor Med Bioeth 40:253–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11017-019-09502-y

van Zaalen Y, McDonnell M, Mikołajczyk B et al (2018) Technology implementation in delivery of healthcare to older people: how can the least voiced in society be heard? J Enabling Technol 12(2):76–90. https://doi.org/10.1108/JET-10-2017-0041

Hampson C, Morris K (2018) Research into the experience of dementia: methodological and ethical challenges. J Soc Sci Humanit 1(1):15–19

Kühler M (2022) Exploring the phenomenon and ethical issues of AI paternalism in health apps. Bioethics 36(2):194–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12886

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to members of the advisory committee for this review: Bonnie Augier, Stéfanie Blain-Moraes, Marie-Pierre Gagnon, Fabrice Jotterand, Félix Pageau, François Paquette, Julie Robillard. We wish to thank members of the Pragmatic Health Ethics Research Unit for constructive feedback on a previous version of this manuscript. Special thanks to Monique Clar, librarian at the Bibliothèque de la santé de l'Université de Montréal for help in developing the review protocol and to Wren Boehlen and Grace Feeney for editorial assistance. Preparation of this review was partly supported by a pilot project grant from the Observatoire international sur les impacts sociétaux de l’IA et du numérique (OBVIA). ER’s research is supported by a career award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec—Santé (FRQ-S).

Funding

Preparation of this review was partly supported by a pilot project grant from the Observatoire international sur les impacts sociétaux de l’IA et du numérique (OBVIA). ER’s research is supported by a career award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec—Santé (FRQ-S).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Fardeau, E., Senghor, A.S. & Racine, E. The Impact of Socially Assistive Robots on Human Flourishing in the Context of Dementia: A Scoping Review. Int J of Soc Robotics 15, 1025–1075 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-023-00980-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-023-00980-8