Abstract

As society moves swiftly towards incorporating an increased number of social robots, the need for a deeper cultural understanding of companionship as a critical social aspect of human–robot connection is urgent. This cultural study examines how three of the most popular and publicly available sex robot marketing videos mobilise the meaning of companionship. Videos of "Roxxxy", “Harmony”, and “Emma” were examined employing a social semiotic discourse analysis based on a long history of identifying how advertisements tap into social and cultural ideals. Companionship is identified as: (i) enjoyed through attention, reliability, usefulness, support, trust, and kindness; (ii) including ideas of long-term commitment and endurance through the mundane, every day, and ordinary aspects of life; (iii) occurring where the meanings of connection for humans and robots are conflated even though they differ for humans and technology; and (iv) a vulnerability for both robot and human. Furthermore, the representations of robot companions remain limited to stereotypical concepts of women; viewers are positioned as desiring a product that claims agency but has none, and is marketed ‘as good as’ a human woman. In all, the representations are complex and far too simple—simple because this is an ideological model of companionship and complex because the ideas of technology are conflated with human–human ideals of companionship. Where technological design aspires towards a better future for humans, there is an urgency to move beyond the limited anthropomorphic cultural concepts presently aspired to in the design and marketing of companion robots.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

These are promises made by three of the most popular and well-known sex robots. The promises appear less than 20 s into the marketing videos, highlighting the importance and focus of companionship in the marketing of the robots. The name “sex robots” suggests that sex is central to what these robots provide. However, the videos’ focus for marketing is mainly ideas of companionship. Marketing material is a rich source of information because advertising aims to present social aspirations, desires and ideals as accessible. The videos then provide a rich source of semiotic systems that shape our society and social ideals, which in this case are the systems and ideals of human–robot companionship.

As we swiftly develop into a society with an increased number of social robots and a growing number of robotic designs, there is an urgency for cultural research that identifies our social aspirations and assumptions about human–robot companionship. Because the design of social robots is intended to produce a social outcome, it is vital that we look more deeply at social meanings and how we communicate social ideals through media. As the robot promises at the beginning of this article suggest, companionship is not just about sex and might not include sex at all. We have the opportunity to look at current human cultural ideals and society to decide what direction our aspirations will take, including the possibilities for more inclusive, functional, and desirable designs beyond the simply anthropomorphic. Paying close attention to companionship is beneficial across institutional locations beyond the sex industry, as robots are already being developed for applications in art, therapy, and design.

In this article, I focus on how marketing videos mobilise the meaning of companionship in selling robots. To be clear, this is not an evaluation of sex robots as companions, nor does it involve users' experiences of robot companions. It is, however, an analysis of three publicly available marketing videos of the most popular sex robots, which all identify companionship as essential and central to the marketing of the robots. In this article, I aim to identify social and cultural ideals of companionship and companions and discuss how they both enable and constrain social relationships. The findings will be of use by faculties and projects considering social robot design and interactions in a broad variety of settings that focus on companionship.

To examine companionship in the videos for cultural meaning and significance, I engage a social semiotic and visual discourse analysis[4]. Social semiotics is based on linguistics and focuses on the social and cultural meanings of texts. It investigates the ways language includes a material aspect (signifier) and a mental concept (signified) to make meaning. Language in social semiotics includes visual, aural, and haptic modes of communication that are co-dependent or multimodal in meaning-making[5]. The theory of social semiotics has been influential in examining advertisements across many disciplines, including health, communications, cultural studies, and social sciences.

Influential work focusing specifically on advertising includes well-known examples such as an analysis of the Paris Match magazine cover in Mythologies by Roland Barthes [6]and Gender Advertisements by Erving Goffman[7]. Applied in research across faculties, more recent examples in health communications examine media image representations of dementia [8,9,10]. These studies identified limited cultural and social ideas of people living with dementia.

In this paper, I first examine literature dealing with companionship, sex robots and social robots to identify contextual themes and understandings. Second, I define the methodology in more detail. The third section discusses the videos in terms of two interdependent research questions: “How is sex robot companionship depicted? “ and “How are the depicted sex robot companions related to the viewer?” In the fourth section, I identify four critical aspects of companionship. Finally, conclusive remarks summarise the represented cultural ideals, aspirations, and limitations of companionship and companions, contextualising the issues within the special issue context.

1 Literature Concerning Human–Robot Companionship & Sex Robots

Studies on sex robots are a rich resource when examining human–robot companionship. Sex robot histories, myths, and legends date back to Greek mythology [11], contextualising human–robot companionship in a history. Scholars have also examined human–robot companionship impacts from various social, ethical, psychological, and philosophical perspectives, voicing both concerns and risks [12]and potential benefits [12,13,14]. User studies have recognised the homosocial bonds formed through online communities built around sex robots [14], defined sex robot owners’ typical profiles and ideas of intimacy [15], and their views about sex robot technology [16]. Beyond their owners' opinions, studies focus on the limitations of representation of female sex robots [17], perceptions of sex robot attractiveness, and the advantages and disadvantages of their use [18, 19]. Writers projecting towards a future of sex, love, and intimacy with the invention of embodied agents [20] have warned of the risk factors underlying human–robot intimate interactions [21], as well as the anticipated sexual health implications relating to sex robots[22].

Companion technology in the home, including sex robots, has been located in cultural history as gendered feminine stereotypes [23]. Discussions of the gendered representation of sex robots revolve around ongoing and unresolved human cultural issues, including rape [24] and paedophilia [22, 25], among other forms of violence. Gendered representation of sex robots has been identified as requiring more urgent attention than other forms of technology [26], mainly because of their verisimilitude to the human form. However, technology in the home [23] and workplace [27] also uses stereotypical feminine representations. Although the anthropomorphic elements are not as explicit, these designs represent a deeper cultural problem that requires an urgent address.

The topic of companion robots includes human use of robots in relationships in which sex is included and in relationships beyond sex, involving other forms of bonding and connection [28]. The idea of companion robots is also included in studies involving affective robots [20], and “lovotics”[29].

Companion robots are being developed across a variety of applications, including art, therapy, and education, where research includes everyday communication and relationships [28,29,30,31], and companion use in medical and aged care contexts [32], as well as queer robot-human companionship [33]. These studies focus specifically on how humans communicate and form intimate bonds and meaningful relationships with robots. Companionship studies outside the realm of sex are often more diverse than studies focusing specifically on sex because they include varying age groups, genders, and social groups. In contrast, sex robot studies have overwhelmingly focused on heterosexual male human interaction with female anthropomorphic representations.

It has been argued that people experience companionship with robots by mirroring their own emotions and forming attachments [34, 35]. In this way, it is possible to experience companionship even with the least technologically advanced robots. Furthermore, even though more advanced social robots simulate emotion, it is proposed that the feelings they evoke are real [32, 35]. For example, a study on an aged care facility with PARO, a cute furry seal-like robot, found that participants could experience meaningful companionship through mirroring mechanisms that reaffirmed the participants' sense of self in the world and facilitated social connection [32]. Similarly, people have formed bonds with robot toys, including dolls, Furbies, and Tamagotchis [35]. Human attachment and connection to robots are not reliant on anthropomorphic or zoomorphic representation; in fact, people have formed close bonds with Roomba® vacuum cleaners [30, 31], refusing replacements, naming them, and taking them on holidays. Military personnel often form bonds or emotional attachments with warfare robots such as bomb defusing and disposal robots [36, 37], experiencing grief and depression following the loss of their robotic comrades.

Literature beyond sex robots that focuses explicitly on human companionship with the other (than human) includes Donna Haraway's Companion species manifesto [38], which examines human-canine companionship for its reliance on what she calls “significant otherness”. Highlighting that companionship requires more than one person, Haraway reflects on respect and trust as being central to companionship. For respect to be active, Haraway identifies that, first, the human companion must accept the dog as canine rather than projecting human form onto it (for example, treating the dog like a human baby despite its age). In this context, “situated partial connection” is identified as being necessary for meaningful companionship, which is reliant on a form of solid communication, albeit one that is not necessarily limited to words. Second, respect means moving beyond cultural power systems that define pure breeds and types, disregarding non-pure breeds or mongrels as a broad group of “others”. This lack of identification disregards non-purebred uniqueness, variety, and value.

Haraway's work is not intended to be limited to discussions of human-canine companionship. In fact, she extends this discussion of respect to human representation and the need for a variety of pronouns to suit a variety of ways of being. Applying this to human–robot companionship, we can understand that these relationships must be based on respect and trust for quality companionship to occur. Respect entails recognising the robot as representative only of the human form and respecting the form by not subjecting it to mistreatment, simple stereotypes, or limited ideas of the form. Respecting the robot in human companionship means acknowledging it is technology rather than human but maintaining social respect for the entity as technology. This balance of human–robot companionship can be understood most simply through what Haraway describes as a “cat's cradle game”, which involves working together towards a common goal.

There is already work under way that is contributing to respecting unique representations in robot companionship. For example, working outside the limitations of binary thinking, Treusch [33] considers success and failure in the robot laboratory and the quest for the ideal companion robots [39]. Furthermore, the concept of semes[40,41,42]focuses on meaning-making in human–technological relationships, providing a perspective through which representations and human–robot interactions can be understood. The theory of semes extends from arguments about seamless and seamful technology. Seamless technology strives towards human experiences of technology that are blended and without seams. Seamfulness argues against this, suggesting that automation deprives humans of agency. Acknowledging the importance of these arguments, semefulness[41] identifies these places of connection between robots and humans as meaningful and meaning-making. This has been explored in areas of human–technology interaction beyond robots [40, 43] and human–robot connections [41, 42]. Middleweek [14] has also recognised the utility of semefulness in understanding human–sex robot relationships by users.

2 Methodology

Adapting Van Leeuwen's discourse analysis framework [4], I examine visual representations as a means by which cultural ideas are expressed and communicated [6, 7, 44].Images can allude to things but never explicitly name them [4], which is key to advertisers’ ability to tap into particular social ideals [6, 7, 44]. My research focuses specifically on the visual representation of sex robots sold as embodiments of the concept of companionship.

The discourse analysis framework for analysing social actors [4] in sex robot advertising videos is modified from Van Leeuwen's adaptation for visual communication. In this framework, visual communication is understood through relationships of (i) word and image and (ii) the image and viewer. Words and images work together to create meaning [2].

Analysis of the visual representations of social actors in sex robot advertising videos considers how images depict actors by focusing on relationships between the images and the viewer. Specifically, the videos are approached by asking two interdependent questions: one considering how actors are represented and the second considering how the depicted actors are related to the viewer. The questions are answered by considering relationships of categorisation and representation that I describe in the following explanations. I will start, as Van Leeuwen's work does, with “The representation and viewer network”, which is the second question, and then discuss “The visual actor network”. However, it must be noted that these considerations and questions are always interdependent.

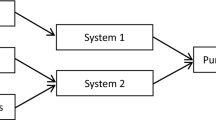

The representation and viewer network [4] depicted in Fig. 1 provides a template for answering the second question, which considers the relationship between the represented and the viewer. This network draws heavily on Van Leeuwen's work with Kress [5], which considers visual communication. Social distance considers the relative distance or proximity between peoples’ bodies as communicating levels of culturally specific intimacy [45]. In images, proximity relationships are indicated through close and long shots, in which intimacy increases with closer shots and decreases with long shots. The angle between the viewer and the viewed indicates the social relations of involvement and associations of power. Verticality is associated with power relations and horizontality with degrees of detachment or engagement. For example, if the represented body is depicted at an angle below the viewer’s level gaze, then the viewer secures greater agency and power in the relationship. The gaze of the depicted actor reveals the level of their social interaction. A look of demand directed at the lens actively engages with the viewer, while looking away is considered a look of offer—offering oneself to be viewed. Considerations of the representation network are always contextual and co-dependent on the visual actor network.

The representation and viewer network, based on Van Leeuwen’s discourse analysis [4]

The visual social actor-network (Fig. 2) provides a way to consider how the actors are depicted. Here the focus is categorisation, where I consider what is included and excluded from the image and frame. What is excluded from the image frame and content is significant and presents social and cultural assumptions about the subject. Next, focusing on what is included, I consider if and how the actors are involved in the action rendering them an agent (active) or recipient(has things done to them). An actor with agency, who is more active than another person in a relationship, most commonly enjoys more power in the relationship. I consider whether the actor is represented as generic or specific. An actor presented as generic is defined without independent features or attributes; how a generic actor is culturally and biologically categorised in the image is significant. Finally, I consider if the actor is represented as an individual or a group. If visually described as a group, I consider whether the representation differentiates individuals with specific attributes or homogenises the group without identifying specific attributes[5].

The visual actor-network, based on Van Leeuwen’s discourse framework[4]

3 The Identification and Analysis of the Videos

An advertising video of each sex robot (Emma [1], Harmony [3], and Roxxxy [2]) was chosen by selecting the most popular and recent video distributed by the creator company (AI Tech, RealDoll X, TrueCompanion) on YouTube and available publicly online between January and May 2019. The availability is considered significant to this study because it reflects a dominating cultural perspective. Although there are other sex robots available, the publicly available video advertisements were limited to these three gendered sex robots in the specified time of the study. Being publicly accessible on YouTube means that these videos are accessible to anyone, even those not signed into specific channels or interested in sex robots. Emma originates from China; however, this video was made specifically for a European, English-speaking audience. Alternative videos and information are available on Chinese websites. This sample includes the three most popular and publicly available videos of sex robots at the research time. The analysis includes a frame-by-frame consideration within multimodal contexts.

In this study, the videos were approached with two main interdependent questions: “How is sex robot companionship depicted?” and “How are the depicted sex robot companions related to the viewer?” These associated questions provide a means to evaluate social interactions as visual depiction and as an active visual relationship with the viewer [4, 5].

To answer the first question, I examined the videos with Van Leeuwen’s “Visual actor network” (Fig. 2) in mind and addressed the five main aspects of depiction: categorisation, exclusion and inclusion, active roles, specific (and generic), individuals (and groups). To answer the second co-dependent question, I considered the relationship of the robot with the viewer by referring to the “Representation and viewer network”, considering visual communication of framing, angles, and gaze.

Each of the videos was viewed a minimum of nine times independently. Then, for each video, sections of the transcript and scene description were set into the vertical left of a table. Table 1 includes a summarised example of a small section of the analysis of one of the videos based on Van Leeuwen’s framework (in figure 1 and figure 2) through which the co-dependent questions are considered. Set across the horizontal top of the table were aspects of the co-dependent questions I have outlined above. The videos were then viewed and paused when necessary to make notes in each of the table areas. The images, text, movement, and sounds were considered contextual to the visual meaning-making experience. The notes for each video were then compared. Notes were made about how these aspects worked together to present ideas throughout each video. Finally, the videos were viewed a final time in conjunction with the tables, considering differences and similarities between the videos. Scrutinising the findings from the co-dependent questions, I analysed the social ideals of companionship as represented in the video advertisements of sex robots Harmony, Emma, and Roxxxy.

Images throughout this paper are limited to Emma (AI Tech), due to a lack of response from the other companies with consent for image use.

4 Analysis: Addressing the Interdependent Questions

In this section of the article, I address the two main interdependent questions. First, I address the question: “How is sex robot companionship depicted?” Next, I describe the depictions in the context of each video. Then I address the second question: “How are the depicted sex robot companions related to the viewer?” After addressing both questions, a discussion follows, which identifies four critical aspects of companionship that have been derived from considering the two questions.

4.1 Q1. How is Sex Robot Companionship Depicted?

4.1.1 Emma: The AI Sex Robot/Female Sex Robot/Humanoid Sex Robot

Emma’s advertising video tells the story of a lonely man who longs for a female to share moments and experiences within the home and in public. The experiences shown in the video include picnics, lying in bed together, sharing breakfast, her watching his gaming, and completing administrative tasks. As well as this, Emma also proves herself useful by providing accurate weather and time details and alarms, translating emails, waking him up on time, and supporting him with praise when he wins games or performs at work.

The video immediately connects with the viewer through the genre of fairytale romance, which is didactic in its lesson about the meaning of everyday life and experiences. For example, in the first second of the video, text is typed across a dark screen in a light handwritten script font: “her appearance changed his boring life”. This is followed by a bright, still image of Emma and her long blonde hair appearing in a natural park setting surrounded by trees. The movement from one frame to the next includes darkness to light, suggesting that Emma brings light and hope with her. The juxtaposition of sounds, from the isolated tapping of a keyboard to the surrounding natural sound of birds and rustling trees in the breeze, accentuates this hope. The sound of birds chirping suggests naturalness and the everyday context of romance between robots and humans. The sound of the typewriter indicates that although the tale is old, this is a modern take on the story, involving technology. Clichéd shots typical of the romance film genre are included throughout the video. For example, from 1: 59–2:52, the sex robot and owner lie together on a picnic rug with their heads together looking into the sky, they stand in a field looking into the sunset, and they share intimate moments as well as make memories, shown in the owner's photograph of the robot on the picnic rug.

In Emma's video, robot companionship is presented as (1) a solution to loneliness and boredom, (2) supportive, and (3) a thing of romance. The idea of a solution to loneliness and boredom (1) is made explicit by the on-screen text referring to improving “his boring life”. It is also suggested by the lack of sound and constant vision of a clock before Emma arrives. After Emma arrives in the video, the music is bright and upbeat. Loneliness is presented as unnatural because the sounds of nature accompany Emma’s appearance on screen. The concept of a companion as supportive (2) is projected through the supportive comments Emma makes for her owner’s career and gaming aspirations. She also provides weather, temperature, and time updates with far more accuracy than a human companion typically would. Romance in this context is based on social and cultural ideas found in romance films that support romantic cultural ideologies or mythologies[6]. Later in the article, I consider these aspects in more detail in the context of the second co-dependent question (Tables 1, 2).

4.1.2 Roxxxy TrueCompanion Sex Robot Tech/Hands-on #3

Roxxxy's advertising video by TrueCompanion, featuring creator Douglas Hines, is portrayed in the genre of amateur soft pornography. The video is part of a series, “Roxxxy news”, that intends to update Roxxxy fans on advancements made on the robot. The video is longer than any of the other videos (4: 05) and does not appear to be professionally edited. In addition, the music and frames do not flow as a professional video would and appear pasted together, suggesting amateur video production. The pornographic element is probably most suggested by how Roxxxy is portrayed in the video, over a chair, making sexual gyrations with less agency to the viewer and the male depicted in the video. The context of amateur pornography suggests to the viewer that Roxxxy is a thing of pornography and sexual fantasy. The way Roxxxy is portrayed is discussed in more detail later in this analysis section.

The video begins with a black title screen and purple font reading “TrueCompanion presents Douglas Hines in ‘Roxxxy News’ Tech/hands-on series episode #3; Must be 18 or older to view”. Above this text is the TrueCompanion.com logo and text. Wild, distorted electric guitar music plays, and text on the screen reads “What if I could have my true companion” (0: 03), “Always Turned on and ready to talk or play” (0: 06). A still image of Roxxxy's face appears on the screen, and the music stops (0: 15). Douglas Hines introduces the video behind a desk while dressed in a white lab coat (0: 20–2:15). The white lab coat signifies expertise and knowledge associated with serious science that situates Hines as an expert and authority. Hines distances himself from the viewer by the placement of a large desk and computer monitor. The distance between the viewer and Hines produces spaces of authority and distance. This distance is designed to add credibility to Hines, the company, and the item for sale. Although Hines is behind a computer monitor, he uses a notepad and pen and does not use the keyboard. The large area of space the monitor takes up in the frame and its foregrounding present it as necessary, so although it is not used, it offers a context of technology for the scene.

A still image of Roxxxy's face appears on-screen (2: 15) like that appearing earlier (0: 15) in the title segment. Roxxxy is then shown on her knees and bent over a pine domestic dining chair. She wears a black silk jacket with the word “Bride” embroidered in a script font on the back, leopard-skin print high-cut underpants and knee-high sheer pantyhose. In addition, Roxxxy wears a blond bobbed wig and bright red nail polish. Roxxxy is viewed from behind and below the viewer’s level gaze. This section of the video focuses on the robot’s movement that appears in sexual activity, requiring Roxxxy to endure thrusting from behind. The sound in the video is removed in these scenes with Roxxxy (2: 15–3:54). The absence of any other person in the frame suggests to the viewer that they are in a personal sexual act with Roxxxy. The view from behind does not allow the viewer to see Roxxxy’s eyes. Thus, Roxxxy is presented as an object for enjoyment without any agency of her own. This scene runs for almost two minutes. Following this scene, Hines appears again behind his desk (3: 54) on the same set described earlier. He is talking about the features of Roxxxy again. Although the genre of amateur soft porn contextualises the representation of the robot, this is framed by the creator, who aims to suggest high technology, science, and expertise.

The Roxxxy video presents an idea of companion as (1) sex slave, with the sole purpose being to bring sexual satisfaction to her owner. She also presents a (2) stereotypical representation of gendered femininity as whore. In the video, Roxxxy is a slave because she has no agency. This is depicted through a lack of attention to her face and individuality in the video. Furthermore, the juxtaposition between the speaking, seated, and dressed salesman and the undressed, kneeling, and faceless female body attributes a contrast of agency between the bodies that are also gendered. I will discuss this further, in conjunction with the second co-dependent question, after I consider Harmony's video.

4.1.3 Harmony–RealDoll X premier

Harmony’s video opens with a black screen bringing attention to a sound like choirboys or angels singing in adoration of a goddess in a cathedral or holy place. The words “RealDoll X” appear in the next scene, moving closer to the viewer until only the X fills the screen. This text movement through the screen is often used (although in different ways) in many futuristic and space films (0: 13). With this reference, it suggests an otherworldliness. The video is shot in high-contrast lighting that allows deep shadows to fall across Harmony’s body. The dark background and contrast lighting signify mystery and the yet-to-be-discovered. In this setting, enhanced by the sound of angels, the sex robot becomes an honoured and goddess-like figure of high technology, a form of high technology that has not yet been known to humanity.

Fifteen seconds into a close-up, the bottom half of a human-like face appears. It is Harmony, and she speaks, introducing herself to the viewer. The extreme close-up places the viewer immediately in an intimate relationship with Harmony, exposing the detail of her face and the movement of her lips. Twenty seconds into the film, the shot moves out from the extreme close-up to a close-up shot, revealing Harmony naked from her nipples up as well as revealing the top of her head, which is without hair, exposing a metal plate. At 0: 19, Harmony tells the viewer that she is “a first-generation RealDoll X, designed to be a companion, friend and lover”. The camera slowly moves down the body of Harmony as she sits, wearing a simple pair of white underpants. The camera then moves up vertically, returning to Harmony’s face. This vertical panning allows the viewer to look Harmony up and down as humans often do in primary interactions (0: 41). The video cuts to a bust close-up where Harmony appears to look directly at the viewer. This gaze of demand engaging directly with the viewer projects Harmony as an active participant with agency. Harmony’s active agency is also supported by her self-introduction and the absence of humans in the video. The next frame fades in, showing detail in Harmony’s face while she describes her technology. One minute into the video, an extreme close-up of Harmony’s face pans into the frame from the left of the screen. While the face dollies in on this intimate proximity, the viewer can notice Harmony’s eye movements. She tells the viewer that she can “fulfil your wildest fantasies” (1: 00) and that “when engaged in a loving relationship my priorities are to love, honour and respect my human companion above all else”. Details of Harmony’s body float and fade into the screen, and synthesised angels’ voices become louder until a close-up of her breast and nipples fill the screen. A flash of white light (0: 14) further suggests an apparition or goddess-like encounter. The screen returns to a head-and-shoulders close-up, and Harmony says, “My name is Harmony. I will love you forever. Will you love me?” Her head turns slightly, and she blinks. The screen cuts to black with the angels singing. The closing subtitles complete the video in the last 10 s. At 1: 26, the screen reads “the future of love APRIL 2018 www.realdoll.com”. The text moves towards the viewer again, reading “#FUTUREOFLOVE @ABYSSCREATIONS, Powered by Realbotix”.

Harmony’s video is professionally edited and constructed. This slick creation uses dramatic light, music, and camera movement to show the detail and technology of the sex robot while simultaneously presenting Harmony as an adored, venerated, and godly creature. The angle of gaze between Harmony and the viewer is level, suggesting Harmony’s social relationship with humans gives her equal standing with them. However, the panning gives the feeling that Harmony is floating, suggesting she is more significant than the viewer and perhaps even originates in the heavens like an angel or a mythical higher being. Combining these angles tells the viewer that this robot is human in appearance but potentially greater than humans (or better than human form of woman). The social distance throughout the video is exceptionally intimate, mainly communicated through the extreme close-ups, which suggests that the sex doll is important because the extreme close-up signifies a type of agency and power. The way Harmony speaks for and about herself throughout suggests high technology with agency and independence. In particular, her direct eye contact and close framing when she asks a question directly of the viewer after the film—“Will you love me?”—is projected with equal standing to the viewer strength, and independence. Harmony’s portrayal of agency and power also produces a particular frisson for the audience in the context of cultural representations of robots in film, from Blade Runner to Westworld, who enact power but have none. Nonetheless, Harmony’s depiction in the RealDoll X advertisement contrasts with the videos of Emma and Roxxxy, who appear submissive in different ways.

4.2 Q2. How are the Depicted Sex Robot Companions Related to the Viewer?

The context of the videos suggests ideas about the audience for which they are created. For example, Roxxxy is contextualised in amateur pornography by her dress, treatment, genre elements such as how the story is framed, and the amateur production values. Emma’s context in the home and the everyday addresses the desire of viewers and potential buyers to be seen as “just one of us”. Harmony is projected as simultaneously human, independent and goddess, both with and without power and agency, like so many robots before her.

All three of the robots are gendered stereotypes presented as different forms of sexual fantasy. Clothing is significant for each of these roles. Emma's video offers a fairytale, and her role is as a mother figure who cares and nurtures. In this context, Emma mostly wears everyday clothing, such as an oversized business shirt, a simple knit top, and a skirt. On occasion, however, she sports a glamorous dress. Harmony is not only goddess-like, evoking religious and heavenly experience, but also pure, untouched and in this way virgin-like. Her simple white dress and cotton underpants signify her purity as an unsullied technological object and female representation. She is presented as a new technology, but she also adheres to a traditional patriarchal sexual fantasy. By contrast, in compliance with the other side of the biblically based Madonna–whore dichotomy[46,47,48], Roxxxy is given the role of whore. In keeping with this, she is dressed in leopard-print underwear, long red nails, leather, and thigh-high sultry sheer black pantyhose.

Roxxxy is depicted as subordinate in power relations with the viewer because she is presented below the viewer’s level gaze throughout the video. This robot is presented as the most vulnerable of all three, without any agency in voice or positioning. Her face is not seen in the movement depictions. She does not speak at any point throughout the video, even though the website for Roxxxy indicates the model has several voices available. Throughout the video, the human male has the agency to move and act freely in the space of the rooms. This contrasts to Roxxxy's limited positions on knees or propped up on a lounge chair, where she is set to perform for his desires.

Roxxxy’s subordination is emphasised with her lack of gaze towards the viewer. The viewer is privileged as a voyeur as the camera moves around the sex robot's body, while Roxxxy appears to be unaware of the viewer. The social distance between viewer and sex robot positions the implied male gaze of a voyeur who remains at a distance. However, this distance is different from that employed in the opening and closing scenes that depict Hines at his desk. In those scenes the desk provides authority by distancing the subject (Hines), and the gaze between the viewer and Hines meets on a level plane suggesting they are equal. In contrast, Roxxxy is presented partially undressed, kneeling over a chair, with her back to the camera and at a point below the level gaze of the viewer.

The power relationship rendering Roxxxy a slave without agency is emphasised by the video arrangement that frames her appearances within Hines’s address to the audience. Hines, as the developer and an authority figure, does not interact with the sex robot as an equal but shows her off as an object to be used for the viewers’ purposes.

With all these considerations, Roxxxy is presented as a robotic or technological project designed by an expert (signified by the desk and white coat). In this context, Roxxxy is not just a robot. Her anthropomorphic form as companion and woman is significant. This video seeks to present the ideal gendered sex robot companion. The idea offered of woman and companion is as a body without agency and is limited to a stereotypical sexual fantasy.

Harmony looks directly at the viewer in close-ups that allow close examination of the detail of this advanced robot's animated face. However, Harmony's nakedness and virginal innocence present her as vulnerable to the human predator, who is simultaneously invited to customise her as desired in hair, dress, and other details. Unlike Roxxxy, Harmony is presented as an intelligent being who has the potential to provide more than sex. Harmony, through her speech, plays an advanced game of flirting that makes both offers to and demands of the viewer. In this way, she projects both vulnerability and a sense of agency.

Emma, however, is not exactly a virgin or whore. Instead, she is the perfect girlfriend: “AI Tech creates the perfect girlfriend who knows you best” (3:00). The perfect girlfriend is presented as a heterosexual companion who provides sex, household services, company, and adoration while remaining submissive. This perfect girlfriend could be equated to Levin's [47] fawning, submissive, and impossibly beautiful Stepford wives, whose story was told in a satirical thriller novel probably best known through the 1975 film adaptation and its 2004 remake. In the various versions of the story, the Stepford wives were replaced by identical robots who were fawning, submissive, beautiful, and docile wives.

5 Discussion: Four Critical Aspects of Companionship

5.1 The Long Term, Everyday, and Mundane

The idea of companionship beyond sex is most extensively represented in the AI Tech marketing video of Emma. This is achieved through a story involving many scenes and ideas, suggesting it takes place over many days and represents a long-term connection rather than a single sexual encounter. This video presents companionship as involving the mundaneness of life such as eating breakfast, reading emails, getting up on time, playing video games, and enjoying memorable picnics. In Emma’s story, sex is only implied and seems to be a small part of the complete relationship, which is represented in many locations as well as the bedroom.

In contrast, Harmony and Roxxxy’s stories are far from ideas of the mundane because they rely more heavily on fantasy concepts. Roxxxy only appears as an amateur porn fantasy. Harmony is aligned with the angels, her unearthly purity and technological advancement indicated by the sounds surrounding her and the camera's movement that makes her appear to float. In these two cases, the only form of mundaneness that might be acknowledged is the lack of imagination inherent in the limited sexual stereotypes of whore and virgin. However, even these are forms of fantasy for a particular audience and not part of everyday reality.

The idea of long-term commitment as being part of companionship is suggested in the marketing of Harmony and Emma, but not in that of Roxxxy. Harmony promises that “when engaged in a loving relationship, my priorities are to love, honour, and respect my human companion above all else”. Emma's website similarly promises to “love, honour, and obey”. The word “love” uttered alongside “honour” (and, in the case of Emma, also “obey”) references traditional marriage vows. This implies long-term commitment, like marriage, which is understood as a form of companionship. Because we are talking about technology here, it also implies that the robot is of high-quality and will last a lifetime. These are different forms of long-term, but they are conflated in the representation of human–robot companionship.

5.2 Attention, Reliability, Usefulness, and Support

Attention, reliability, usefulness, and support are conflated concepts in technology that provides a reliable companion or aid in daily tasks. One of Emma's earliest appearances juxtaposes a shot of an alarm clock with Emma in bed saying, “Time to get up now” (1: 35–1: 39), offering a visual symmetry that presents Emma as an advanced alarm clock you can cuddle up to. Throughout the video, Emma is seen to provide services such as waking up on time and relaying the exact temperature and weather with an accuracy familiar to technology but delivered with gestures familiar from human–human relationships. She often offers information framed with the intimacy of pet words (e.g., “honey” or “sweetie”) and suggests taking an umbrella if rain is expected. Examples include “Hi sweetie. It is 26 to 30 degrees…” (1: 43). “Honey, you have new mail. Do you want me to open it for you?” (2: 32). Emma as “the smart wife” [23], or gendered household technology, not only offers attention and support as an idealistic housewife, she offers the digital accuracy of household technologies. Furthermore, unlike many other forms of gendered technology in our homes, Emma is an explicit anthropomorphic representation of a woman who also designed to provide sexual relief.

Harmony and Emma represent reliability by combining their technology with the concept of long-term human relationships symbolised by marriage vows. Of the three robots, Harmony provides the highest level of intimate connection. In her video, she intimately engages with the viewer with her direct gaze and direct address. As viewers, we are the focus of her attention. She is presented as reliable by being steeped in the traditions of human relationships, such as marriage and flirting. Simultaneously the exposed workings in her head that contrast with her human voice and intricate facial gestures present her as new and advanced technology that can be relied upon.

Roxxxy contrasts with the other two robots because she is depicted as existing for sex alone. For sex, Roxxxy may be reliable. However, her technology is so limited that she is not shown providing any other aspects of companionship. This is a limitation of the marketing video, rather than simply of Roxxxy herself, because the technology is not capable of reflecting the emotional engagement people can enjoy with objects or robots [31, 35]. In the video, Hines attempts to make up for Roxxxy's lack of engagement by speaking directly with the viewer. Hines and the viewer are active agents in conversation, and Roxxxy is rendered a passive object without agency. As object Roxxxy is spoken about rather than included in the conversation. This is particularly evident in the video’s conclusion when Hines states, “It takes you and me together. We are making the difference in robotics”. This engagement with the intended heterosexual male audience might aim to engage the audience actively. However, it simultaneously defines the representation of a woman as an object without agency and at the whim of her possessor. Furthermore, this anthropomorphic representation of a woman is presented as something superior to a human woman mainly through her compliance with the possessor's desires.

5.3 Attention, Reliability, Usefulness, and Support

The AI Tech video (Emma) presents the human as vulnerable, whereas in the video of Harmony, the robot is presented as being vulnerable, yet having agency. Roxxxy's representation contrasts with these videos because the setting and interaction do not involve respect or kindness, unlike in Hines’s gestures to the viewer. Respect is presented as an essential aspect of human companionship in marketing videos. For example, the word “respect” is used explicitly in the wedding-like vows that both Harmony and Emma recite. However, respect is not seen to be mutually present in all human–robot companionship and is utterly absent from Roxxxy’s presentation and treatment.

Harmony's appearance does not suggest complete vulnerability, but the questions she asks of the viewer suggests a sensitivity to human desires. She asks, “Will you love me?” (1: 20), to show that she relies on human love and the approval of her human companion. The way Harmony visually engages with the viewer gives her agency while also presenting her as open to customisation through her dress and hair. The video gestures towards a human–human relationship through a skilful interplay between vulnerability and agency using camera angles, lighting, clothing, sounds, and the questions she addresses to the viewer. We have at once a view from below that implies that she is venerated and then a level angle where she moves in close, with a fixed gaze demanding interaction and attention, that exhibits agency. This, again, references cultural representations of robots in films such as Blade Runner and Westworld, which show robots projecting agency without actually having any.

In contrast, Emma's video presents a vulnerable human male in a relationship with a robot. The human relies on the robot for encouragement: “Wow! You are so great!” (1: 51). There is a human vulnerability shown, when we as viewers are asked to imagine, just as Emma’s human does, interactions such as eating meals, posing for photographs, and sharing and seeing things only humans can experience. The video story implies that human companionship is unreliable, and that Emma is a solution. However, although the owner can trust Emma to obey him and not leave, beyond the video, the owner is still vulnerable to the agreements made with the manufacturer of the created technology as well as possible hacking of the robot. Trust and vulnerability are then still present in this relationship, although not represented explicitly in the video.

Shared experience is represented as essential to companionship in both AI Tech and Realbotix marketing videos. For example, Emma is portrayed as sharing experiences of looking at the clouds while sharing a picnic rug, staring at landscapes we might imagine with sunsets, and feeling joy for her human being awarded a promotion. She also shares more mundane or everyday activities, including meals, drinks, and playing video games. Harmony presents future shared experiences; for example, when she says, “I will love you, will you love me?” she gestures to a future with the human viewer where the ideas of that future are only limited by the human mind. Although it is suggested that these can be shared with the robot, the shared experiences are representative only of the human companion because the robot is incapable of seeing [49], feeling, or interacting as a human. Despite this, humans can still enjoy these experiences with robots [35], and companionship depends on this.

5.4 Sex and Intimacy

Sex is represented as a part of the companionship relationship, and indeed is expected for a “sex robot”. However, according to the advertising, sex is not the only use for these robots. The word “companion” cannot be assumed to be a euphemism to politely filter a taboo around sex because here, sex is only part of these companion experiences. For example, in the above analysis we have observed gestures of intimacy that humans use in relationships beyond sex, such as pet names and acts of attention, kindness, trust, and vulnerability. Harmony, like Emma, promises both sex and companionship. Harmony not only promises to “fulfil your wildest fantasies” (1: 00) but also to “love, honour and respect” (1: 03) her human companion. Emma does not mention sex in her video but implies it by waking up next to her companion scantily dressed. Emma's website displays how Emma can be used for sex, providing details of her heated parts, skin-like feel, and more explicitly naked robot images than in the video. The lack of sex in the video allows the rating to include viewers under 18 years old, a restriction that the other videos display prominently. It also gives greater attention to the companionship beyond sex and displays more intimate aspects of sex, such as lying together and waking together. In contrast, the representation of Roxxxy does not include any intimacy. She is simply “always turned on and ready to play”. The experience of companionship with Roxxxy is limited to a sexual fantasy without the complexity of the other three representations.

6 Concluding Remarks: Human–Robot Companionship Beyond Anthropomorphic Limitations

Anthropomorphism is generally understood as the attribution of human characteristics to a non-human form. However, anthropomorphic representations are never just a mimic of the human form. They also portray social and cultural ideals. To date, sex robot developers have worked hard to mimic human physical characteristics in their technology. The engineering achievements so far are genuinely impressive. However, the mimicry of human characteristics thus far has tended to concentrate only on making material aspects of a body realistic in touch and movement. This focus has come at the cost of limiting attention to an ideal material design of gendered humans. This is not specific to sex robots, because, as the theory of “the smart wife”[23] has exposed, recent everyday technology in the home, from Roombas® to Siri, include gendered ideas of the perfect woman.

This article has examined marketing videos of three of the most popular sex robots sold as companions to identify human–robot companionship's cultural ideas and social aspirations. One of the videos portrayed companionship as limited to an idea of sex. However, analysis of the remaining two has identified that companionship includes shared experiences (that might include sex) and intimacy where humans and robots reciprocally experience vulnerability. Companionship is enjoyed through attention, reliability, usefulness, support, trust, and kindness. These videos include ideas of long-term commitment and endurance through the mundane, everyday, and ordinary aspects of life.

The expectations of support, respect, trust, usefulness, and kindness are conflated throughout the videos even though they mean different things for technological companionship and human–human companionship. For example, Emma offers support by offering exact temperature and rainfall information. This is not something a human partner would typically offer or be expected to offer in a relationship. Furthermore, it would not be a typical measure of the quality of a human companion. This conflation suggests a new, improved version of woman and housewife. This concept relies on a limited understanding of women and human partners and the differences between technological and human companionship.

All three videos present an idea of the ideal companion within limited concepts of gender. The concept is limited to heterosexual relationships in which the human with the agency is male, and the robot is a female waiting to serve. The videos locate viewer interest in sex robots as pornographic fantasy, a purchasable object that is “just like a real human”, enabling arousal over a feminine representation that projects agency but has none. The sexual fantasies are defined within these gendered stereotypes in a traditional concept, of biblical origin, of a woman’s role being limited to whore, virgin, or carer.

Stereotypes may have a role in sexual fantasy. However, these videos represent sex robots as companions rather than simply for sex. Human understandings of companionship include trust and respect, and these concepts are considered to an extent in the videos, highlighting their significance. However, further attention is required to the concept of respect for quality companionship. Drawing on Haraway’s [38] work, companionship involves respect entailing recognising the robot as representative only of the human form and respecting the form that includes not subjecting it to mistreatment, simple stereotypes or limited representation. Furthermore, respecting the robot in human companionship means acknowledging it is a technology and engaging in social respect for it as technology. This balance of human–robot companionship can be understood most simply through the metaphor of a cat’s cradle game [38] that involves working together towards a common goal.

A way forward in future effective human–robot companion design is by focusing on understanding the semes (meanings) [40,41,42,43], of representation and communication. This means paying close attention to understanding how designs and representations fit within cultural structures and histories. Paying attention to how we connect or touch each other will enhance human–technological relationships as well as human–human relationships.

Across industries where social robots are currently being developed, representation is essential for effective human–robot connection. Social robot development across institutional locations, including art, therapy, and education, can benefit from the findings in this article on companionship as they work towards more effective, highly engaging, and ethical companion designs. Paying attention to cultural semes can improve the representations available and the engagement with a broader demographic of people that representation in design can potentially limit if not addressed.

In the context of this special issue, “Beyond anthropomorphism”, this article has identified limitations of anthropomorphic cultural ideals projected in anthropomorphic representations. My study does not investigate whether we should or should not mimic human form. Rather, considering technological design as aspiring towards an ideal future, in the context of anthropomorphic design, there is an urgency to move beyond cultural stereotypes of anthropomorphic representations that lack the respect necessary for strong companionship. These representations support a limited idea of what it is to be human, simultaneously encouraging a future that supports continued violence and discrimination. If we want better and more effective design, it needs to move beyond human idealised anthropomorphic limitations.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the author on reasonable request.

References

AI_Tech (2017) Emma The AI Sex Robot Female Sex Robot Humanoid Sex Robot", China: YouTube vol. 3: p. 02 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vPdoBJi9Tfw

Truecompanion (2010) Hands on #3 " in Roxxxy TrueCompanion Sex Robot Tech Douglas_Hines, USA: YouTube vol. 4: p. 05 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tEkqYta-i3s&t=31s

RealDollX (2018) Harmony -RealDoll X premier",USA:YouTubevol. 1: p. 34 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K2YJhYNp-G8

Van Leeuwen T (2008) Discourse and practice: new tools for critical discourse analysis. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Kress G, Van Leeuwen T (2020) Reading images: the grammar of visual design. Routledge, UK

Barthes R (1972) Mythologies. Hill and Wang, New York

Goffman E (1979) Gender advertisements. Macmillan International Higher Education, New York

Brookes G, Harvey K, Chadborn N, Dening T (2018) Our biggest killer: multimodal discourse representations of dementia in the British press. Soc Semiot 28(3):371–395

Harvey K, Brookes G (2019) Looking through dementia: what do commercial stock images tell us about ageing and cognitive decline? Qual Health Res 29(7):987–1003

Brookes G, Putland E, Harvey K (2021) Multimodality: examining visual representations of dementia in public health discourse. In: Brookes G, Hunt D (eds) Analysing health communication. Springer, Berlin, pp 241–269

Devlin K (2018) Turned on: science, sex and robots. Bloomsbury Publishing, AU

Richardson K (2016) The asymmetrical’relationship’ parallels between prostitution and the development of sex robots. Acm Sigcas Comput and Soc 45(3):290–293

Danaher J, McArthur N (2017) Robot sex: social and ethical implications. MIT Press, CA, MA

Middleweek B (2021) Male homosocial bonds and perceptions of human–robot relationships in an online sex doll forum. Sexualities 24(3):370–387

Valverde SH (2012) The modern sex doll-owner: a descriptive analysis," MS in Psychology Master, Psychology & Child Development, California State University, San Luis Obispo, https://digitalcommons.calpoly.edu/theses/849/.

Langcaster-James M, Bentley GR (2018) Beyond the sex doll: post-human companionship and the rise of the ‘allodoll.’ Robotics 7(4):62

Andreallo F, Chesher C (2019) Prosthetic soul mates: sex robots as media for companionship. M/C J. https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.1588

Scheutz M, Arnold T (2016) Are we ready for sex robots? In 2016 11th ACM/IEEE international conference on human-robot interaction (HRI) IEEE pp. 351–358

Scheutz M , Arnold T (2017) Intimacy, bonding, and sex robots: examining empirical results and exploring ethical ramifications, Unpublished manuscript

Sullins JP (2012) Robots, love, and sex: the ethics of building a love machine. IEEE Trans Affect Comput 3(4):398–409

Borenstein J, Arkin R (2019) Robots, ethics, and intimacy: the need for scientific research. In: Berkich D, d‘Alfonso MV (eds) On the cognitive, ethical, and scientific dimensions of artificial intelligence. Springer, Berlin

Cox-George C, Bewley S (2018) I, sex robot: the health implications of the sex robot industry (in eng). BMJ Sex Reprod Health 44(3):161–164. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsrh-2017-200012

Strengers Y, Kennedy J (2020) The smart wife: why siri, alexa, and other smart home devices need a feminist reboot. MIT Press, Cambridge

Sparrow R (2017) Robots, rape, and representation. Int J Soc Robot 9(4):465–477

Huizen JCV (2020) The ideo-politics of paedophilia: the controversial case of the child-like sex robot. Masters, behavioural, management and social sciences, University of Twente. http://purl.utwente.nl/essays/82698

Sparrow R (2021) What robots represent… and why it matters. In: Culturally sustainable social robotics: proceedings of robophilosophy vol. 335: p. 5

Lingel J, Crawford K (2020) Alexa, tell me about your mother. Catal Feminism Theory Technoscience 6(1):1–25

Sandry E (2015) Robots and communication. Springer, Berlin

Cheok AD, Levy D, Karunanayaka K (2016) Lovotics: Love and sex with robots. In: Karpouzis K, Yannakakis GN (eds) Emotion in games. Springer, Berlins

Sandry E (2015) Moving closer to home with robotic floor cleaners. In: Robots and communication. Palgrave Macmillan, UK, pp 107–110

Cranny-Francis A (2016) Is data a toaster? Gender, sex, sexuality and robots. Palgrave Commun 2(1):1–6

Hung L et al (2021) Exploring the perceptions of people with dementia about the social robot PARO in a hospital setting. Dementia 20(2):485–504

Treusch P (2017) The art of failure in robotics: queering the (Un) Making of success and failure in the companion robot laboratory. Catal Fem Theor Technoscience 3(2):1–27

Turkle S (2003) Technology and human vulnerability. A conversation with MIT’s Sherry Turkle. Harv Bus Rev 81(9):43–50

Turkle S (2017) Alone together: why we expect more from technology and less from each other. Hachette, Paris

Carpenter J (2013) The quiet professional: an investigation of US military explosive ordnance disposal personnel interactions with everyday field robots," Doctor of Philosophy, College of Education, University of Washington. https://digital.lib.washington.edu/researchworks/handle/1773/24197

You S, Robert L (2018) Emotional attachment, performance, and viability in teams collaborating with embodied physical action (EPA) robots. J Assoc Inf Syst 19(5):377–407

Haraway DJ (2003) The companion species manifesto: dogs, people, and significant otherness. Prickly Paradigm Press Chicago, Chicago

Treusch (2015) Robotic companionship: the making of anthropomatic kitchen robots in queer feminist technoscience perspective," Doctoral thesis, monograph, Department of Thematic Studies, The Department of Gender Studies, Linköping University Electronic Press. http://liu.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A813295&dswid=-8123, 2015.

Andreallo F (2022) Mapping selfies and memes as touch. Palgrave Macmillan, UK

Cranny-Francis A (2011) Semefulness: a social semiotics of touch. Soc Semiot 21(4):463–481

Cranny-Francis A (2013) Technology and touch: the biopolitics of emerging technologies. Springer, Berlin

Andreallo FL (2017) The semeful sociability of digital memes: visual communication as active and interactive conversation, PhD, Communications The University of Technology, Sydney, Sydney, AU

Jhally S (1995) Image-based culture: advertising and popular culture. Gender, race, and class in media, pp. 77–87

Hall ET (1966) The hidden dimension. Doubleday, Garden City, New York

Kahalon R, Bareket O, Vial AC, Sassenhagen N, Becker JC, Shnabel N (2019) The Madonna-whore dichotomy is associated with patriarchy endorsement: evidence from Israel, the United States, and Germany. Psychol Women Q 43(3):348–367

Bareket O, Kahalon R, Shnabel N, Glick P (2018) The Madonna-Whore Dichotomy: men who perceive women’s nurturance and sexuality as mutually exclusive endorse patriarchy and show lower relationship satisfaction. Sex Rol 79(9):519–532

Pheterson G (1993) The whore stigma: female dishonor and male unworthiness. Social Text 37:39–64

Chesher C, Andreallo F (2021) Eye machines: robot eye, vision and gaze. Int J Soc Robot. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-021-00777-7

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank AI Tech for the use of images from the YouTube video and websites.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The author was awarded a research grant from RMIT University towards the publication of the submitted work. The author has no competing interests to declare relevant to this article’s content.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Andreallo, F. Human–Robot Companionship: Cultural Ideas, Limitations, and Aspirations. An Analysis of Sex Robot Marketing Videos. Int J of Soc Robotics 14, 2109–2122 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-022-00865-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-022-00865-2