Abstract

How people behave towards others relies, to a large extent, on the prior attitudes that they hold towards them. In Human–Robot Interactions, individual attitudes towards robots have mostly been investigated via explicit reports that can be biased by various conscious processes. In the present study, we introduce an implicit measure of attitudes towards robots. The task utilizes the measure of semantic priming to evaluate whether participants consider humans and robots as similar or different. Our results demonstrate a link between implicit semantic distance between humans and robots and explicit attitudes towards robots, explicit semantic distance between robots and humans, perceived robot anthropomorphism, and pro/anti-social behavior towards a robot in a real life, interactive scenario. Specifically, attenuated semantic distance between humans and robots in the implicit task predicted more positive explicit attitudes towards robots, attenuated explicit semantic distance between humans and robots, attribution of an anthropomorphic characteristic, and consequently a future prosocial behavior towards a robot. Crucially, the implicit measure of attitudes towards robots (implicit semantic distance) was a better predictor of a future behavior towards the robot than explicit measure of attitudes towards robots (self-reported attitudes). Cumulatively, the current results emphasize a new approach to measure implicit attitudes towards robots, and offer a starting point for further investigations of implicit processing of robots.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the next few years, robots may become a part of our daily environment. As in human–human interactions [1], how people will perceive and interact with robots could, to a large extent, depend on their prior attitudes towards these new artificial agents [2]. In psychology, attitudes define the state of mind of an individual or a group towards an object, an action, or other individuals. They constitute mental predispositions to act in one way or another, and are indispensable for the explanation of social behavior [3]. There are two forms of attitudes: explicit and implicit [4]. Explicit attitudes operate on a conscious level and are generally measured through explicit self-reports (e.g. questionnaires), while implicit attitudes rely on unconscious and automatic processes, and are typically assessed via implicit measures (e.g. reaction time paradigms, implicit association test) [5]. Research suggests that implicit attitudes might constitute better predictors of future intentions and behaviors [6], and thus be more representative of real attitudes than explicit declarations. Implicit measures have also proved to be well equipped to predict the behavioral consequences of individuals’ implicit representations [6, 7]. For instance, Amodio and Devine showed that implicit measure of an in-/out-group racial bias can predict the seating distance from an African American target [8]. Similarly, in a study with human resource managers, Agerström and Rooth could predict hiring discrimination based on an obese/normal weight–high performance/low performance stereotype implicit measure [9].

In human–robot interaction (HRI) research, attitudes towards robots have generally been assessed using explicit measures, mostly self-reports, especially the Negative Attitude Toward Robot scale [10, 11]. These explicit measures have been linked to other explicit tools to evaluate robots such as the Robot Social Attribute Scale (RoSAS) [12] that assesses judgements of social attributes (anthropomorphism) of robots using three main dimensions that are warmth, competence, and discomfort [13]. Yet, as in human–human interactions, it can be assumed that attitudes towards robots should arise from both conscious and unconscious processes [2, 14]. However, to date implicit attitudes towards robots have not yet been widely researched. Preliminary research demonstrates that the use of implicit cues (e.g. speech rate, loudness, vocabulary richness, gesture) may be used to adapt robot behavior (speech and gesture) to users resulting in more positive evaluation of HRI [15, 16]. In addition, attitudes have been linked to a tendency to attribute human characteristics to robots, a process referred to as anthropomorphism [17, 18] with positive attitudes being positively correlated with more anthropomorphism [19]. However, while informative, these first pieces of evidence were mainly used in an online interaction setting and are not yet predicting human attitudes towards robots, robots’ evaluation, and more complex social behaviors.

Further, the question whether implicit attitude measures would be better in predicting future behavior towards robots, as compared to explicit measures, is still unanswered. It is therefore paramount to assess the extent to which implicit attitudes could predict the pro-/anti-social behaviour towards a robot in a subsequent HRI. Prediction of pro-/-anti social behaviour is of special interest as pro-social behaviors are a pillar of our society. Acceptance of others in our environment (at meso-, micro- and macro-levels) is associated with positive behaviors while rejection is associated with negative behaviors [20, 21]. To predict in what type of behavior one will engage while facing robots will make it possible to predict the acceptance and successful integration of these new artificial agents.

1.1 Emotion Attribution as a Measure of Robot Perception

As we typically consider robots as belonging to a different group than our human group, we anchored our approach in the intergroup socio-cognitive framework [22]. One interesting measure of intergroup attitudes relates to evaluation of emotions [23]. While some emotions are perceived as common to humans and other species (“primary emotions”; e.g., fear), other emotions are perceived as unique to humans (“secondary emotions”; e.g., regret) [24]. The distinction stems from the fact that secondary emotions rely on higher level cognitive processes, requiring complex abilities and insight, while primary emotions constitute automatic responses to e.g. threatening stimuli [25].

This taxonomy of emotion has been used to study intergroup relationships. Indeed, among interpersonal relationships, one of the most fundamental and robust phenomena is the tendency of people to prefer individuals that belong to their own group (in-group) as compared to another group (out-group). This “in-group favoritism” is known to influence human attitudes towards others and to affect ascription of characteristics (such as emotions) towards others, changing intrinsic representation in observer’s mind [25, 26]. Specifically, studies have shown that members of an out-group are typically described with fewer characteristics that are uniquely human (such as secondary emotions) as compared to members of the in-group [23, 26, 27], while attribution of primary emotions is similar across the groups [28]. Thus, the difference in ascription of secondary emotions between groups might be a proxy measure for semantic difference (or distance) between the groups, manifested as, for example, a deprivation of human characteristics from another individual or a group [26, 29]. This deprivation of human characteristics has been theorized as the dehumanization which posits that individuals are considered with more or less human attributes as the function of the semantic distance that observers embed between them and the target [29,30,31]. Specifically, considering the in-group as the reference, the more an out-group is perceived with secondary emotions, the more its members shall be perceived as members of an own group, i.e. `more human’ (and thus experience less semantic distance between the groups) [29].

1.2 Could this measure of emotion ascription be extended to measuring implicit attitudes towards robots?

Results from preliminary literature on this topic suggest a positive answer. First, Häring and colleagues showed that participants playing cards together with a robot, that belonged to either the in- or the out-group, evaluated the robot from the in-group more positively and with more anthropomorphic characteristics as compared to the robot from the out-group. Further, robot’s group belonging also affected participants’ engagement in cooperation with the robot, demonstrating the behavioural consequence of an a-priori social evaluation [32]. Second, in a study, set in a context of a language test [33], participants interacted with a robot that was presented either: as a member of their own group or another group. Following the in versus out group (robot) manipulation, participants completed a semantic priming task [34]. In the task, participants were first presented with a prime picture depicting a robot or a computer, and subsequently indicated whether the currently presented target word (primary emotion, secondary emotion, or a non-emotional control word) is an emotion (or not). In semantic priming tasks response to a target (e.g., dog) is usually faster when it is preceded by a semantically related prime (e.g., cat), compared to an unrelated prime (e.g., car). Semantic priming occurs because the prime partially activates related words or concepts, facilitating their later processing. The task was developed according to the theories of spreading activation in semantic networks [35]. According to this theory, priming stimuli activate semantically related concepts as they increase the sensitivity to the stimuli displayed a posteriori by making the associated concepts more accessible (facilitation) [36]. Priming is also conceptualized as occurring outside of conscious awareness, relying on implicit processes, and it is assumed to be an involuntary and perhaps an unconscious phenomenon [37]. Thus, it differs from direct retrieval based on explicit memory and can thus be used to measure implicit cognition [38, 39]. The authors showed the first hints, although marginally significant, for implicit emotion attribution: when the robot belonged to participants’ own group, participants showed larger difference in RTs for identifying secondary emotions as emotions following the robot prime (versus the computer prime) than they showed the difference in RTs for primary emotions. No differences were found for the out-group condition [33].

These results suggest that the approach might be suitable for assessing in versus outgroup biases as well as implicit attitudes towards robots. Additionally, the implicit measure was related to explicit evaluation of the robot [22]. According to Nosek, implicit and explicit tools measure distinct but related concepts [40]. Yet, the predictive power of implicit attitudes over explicit attitudes can be expected as the explicit evaluation emerges from individuals’ mind shaped by implicit associations. However, as explicit measures are more malleable, easily controllable and sensitive to context, their correlation with implicit measures are only partial [40].

2 The Present Study

In the current experiment, building up on Kuchendbrandt et al. [33], and the presented social psychology literature, we assessed whether a semantic priming task (implicit measure of attitudes towards robots) could be used to predict explicit attitudes towards robots, explicit semantic distance between robots and humans, the anthropomorphic evaluations, and a behaviour towards a robot in an interactive, real-life scenario. Further, we were interested whether implicit measure of attitudes would be a stronger predictor for a future behavior towards a robot than the explicit measure of attitudes towards robots.

Importantly, in contrast to Kuchendbrandt et al., in order to evaluate participants’ perception of similarity between a ‘robot’ and a ‘human’ concept, we used a human prime as a control condition.

2.1 The Change in the Intrinsic Representation of Robots

In order to assess the relationship between implicit attitudes towards robots and explicit perceptions of robots, along with the semantic priming task (implicit measure), we first assessed participants’ self-reported attitudes, explicit semantic distance between robots and humans, and perceived robot anthropomorphism [41].To evaluate individuals’ representation of robots, we used the theory of dehumanization that describes a disposition towards others in which the observer deprives the other of social or human characteristics. The dehumanization process, theorized by Haslam [29] is based on a modulation of the distance between the representation of what defines the concept of a ‘human’ and what defines the concept of an ‘other’ [29], and has previously been proved to be a reliable measure of robot evaluation [42].

2.2 Pro/Anti-social Behaviors Towards Robots

To assess whether an implicit attitudes’ measure (semantic priming task) could predict participants’ future behavior towards robots, we additionally evaluated participants’ pro versus antisocial behavior towards a robot (NAO) in an interactive scenario. Building upon Bartneck et al., (Bartneck et al., 2007) findings, showing that participants’ perception of robots is linked to the likelihood that participants would switch the robot off (while the robot explicitly requests not to be switched off, saying that it fears it might not be able to wake up again), we set to assess whether also implicit attitudes would predict future behavior towards a robot. For comparisons between predictive power of implicit and explicit measures of attitudes, we additionally assessed the extent to which explicit attitudes’ measure would predict future behavior towards the robot.

2.3 Hypotheses

We hypothesized that: firstly, in the semantic priming task, participants would identify words denoting secondary emotions as emotions faster when primed by a “human” as compared to “robot” concepts, while no RT differences were expected in relation to primary emotions [26, 33]. Thus, we expected a larger difference in RTs to identify secondary emotions as emotions compared to primary emotions following the robot versus the human primes. This is because we expected that a ‘robot’ would be considered as belonging to an out-group, while a “human” would be considered as participants’ in-group [23, 26,27,28]. Secondly, we expected that lower RT difference to identify secondary emotions as emotions, following a human versus robot primes, would be linked to more positive explicit attitudes towards robots, lower explicit semantic distance to a robot (NAO), and a higher attribution of human traits to a robot (NAO). Indeed, as attribution of human traits is sensitive to in-/out- group biases [26, 29], the more participants would implicitly consider robots as different from humans (higher distance in a semantic web), the lower the attribution of human traits was expected [31]. Third, we expected that higher RT difference to identify secondary emotions as emotions, would be linked to higher likelihood to switch the robot off in an interactive situation (consistently with findings showing that implicit attitudes predict behavior [6], and previous research on pro/anti-social behaviour toward robots [43]). Lastly, we expected that implicit measure of attitudes towards robots (RT difference to identify secondary emotions as emotions following robot versus human primes in the semantic priming task) would be a stronger predictor of a future behaviour towards the NAO robot, as compared to the explicit measure of attitude towards a robot (consistently with research suggesting that implicit attitudes might constitute better predictors of future intentions and behaviors [6]).

3 Methods

3.1 Participants

Participants were 37 students (19 females, Mage = 19.4 years, SD = 0.9) from the University Clermont-Auvergne with normal (or corrected-to-normal) vision. They took part in this study in exchange of course credit. Participants did not have prior experience with social interactive robots as assessed during the debriefing questionnaire.

Sample size was determined based on previous studies on primary and secondary emotion attribution in an intergroup situation [23, 25].To achieve the desired power (0.80) for the main hypothesis (i.e. a difference on secondary emotions between human and robot primes), alpha level (0.05) [44], using G*Power 3.1 [45], the minimum required sample size was calculated as 36.

This study was approved by the Statutory Research Ethics Committee IRB-UCA, IRB00011540-2018-23, and was carried out in accordance with the provisions of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

3.2 Procedure

First, participants performed a semantic priming paradigm (a lexical emotion word judgment task) in which they indicated whether a presented word was referring to an emotion or not.

Each trial was designed as followed (Fig. 1): first, participants saw a fixation cross for 500 ms and the prime (either the word “robot” or the word “human”) presented in a blue color for 500 ms that they were instructed to memorize (i.e., prime memory task). Second, a new fixation cross appeared for 500 ms. Following the fixation cross, a target word appeared, and the participants had to indicate whether the currently presented word referred to an emotion or not. To respond they used the S (“no”) and the M (“yes”) keys on an AZERTY keyboard. To facilitate the judgement, the responses’ labels were presented on the left and the right sides of the response screen. The screen faded out after participants’ responses or after 2500 ms. Finally, after a fixation cross (500 ms) the participants were asked to recall the prime (further mentioned as prime recall) by selecting one of the blue-inked labels: ‘robot’ or ‘human’. In order to avoid any spatial priming effect, labels were assigned to the left or to the right part of the screen in a counterbalanced order in each trial. Again, participants used the S (left label) and M (right label) keys to answer this final task with a maximum duration time fixed at 2500 ms. The prime recall task aimed to ensure that the prime was kept active in working-memory during the judgment by increasing the bottom-up activation strength [37]. Indeed, according to semantic priming theories [46, 47] priming effect can only occur if two items are directly linked in a working memory process [48] in the form of a mental model of the task [49].

Participants completed 160 trials (80 with the “human” prime and “80 with the “robot” prime). All characters were written in lower case, bold Courier font, point size 18 and presented on a computer screen on a light grey background.

Second, following the semantic priming task, participants completed the Negative Attitude towards Robots Scale (NARS) [50].

Third, we introduced participants to a NAO robot (NAO, Softbank Robotics) (Fig. 2). The robot interacted with the experimenter through a quick introduction of its social skills (i.e., a short conversation). The experimenter asked NAO to grasp an object and to put it in a marked box. After this sequence, participants rated the robot on two scales presented in a counterbalanced order: the Robotic Social Attribute scale (RoSAS) [12] and the De-humanization scale based on Haslam taxonomy [29, 42].

Finally, the experimenter, with an excuse of going to fill out the participants’ forms, left the room for 2 minutes instructing the participants to switch-off NAO by pressing the button on its chest. Once the experimenter left the room, the robot asked the participants not to press the button by saying “Please don’t unplug me, if I turn off I’m afraid I won’t wake up again”. It repeated the sentence three times or until the participant switched it off. The sentence was launched by a hidden operator (in a connected room) as soon as the participant stood up from the chair.

3.3 Materials

All stimuli were presented in French using Arial font size 18. In the Semantic Priming Task, there were 10 words related to primary emotions (e.g., “anger/colère”), 10 words related to secondary emotions (e.g., “guilt/culpabilité”) and 20 neutral words (e.g., “morning/matin”). Each word was presented two times for each “human” and “robot” prime (160 trials). Emotional and neutral words were carefully chosen by experimenters to control for word frequency according to the gender, the number of occurrence in films subtitles [51], number of letters, and number of syllables [52]. The final list of words and their characteristics are available via Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/hp7cq/.

3.3.1 Negative Attitudes Toward Robots Scale

Participants completed the Negative Attitude Toward Robots Scale (NARS) [41] that aims to explain differences in participants’ behaviour in live HRI studies. The scale consists of three dimensions: (1) negative attitudes toward situations and interactions with robots (e.g., “I feel that if I depend on robots too much, something bad might happen”); (2) negative attitudes toward social influence of robots (e.g., “I would feel uneasy if robots really had emotions”); and (3) positive attitudes toward emotions in interaction with robots (e.g., “I feel comfortable being with robots”). Although the scale is widely used in HRI research [10, 53, 54], according to our reliability scale analysis, taken separately, the factors were not reliable. We used the computation score of the three dimensions that provides the individuals’ general attitudes toward robots, α = 0.85. Questions in the questionnaire were presented in a random order and participants had to rate their level of agreement with each question on a scale going from 1 “not at all” to 6 “totally).

De-humanization Scale. The scale is composed of four dimensions. Two sub-scales illustrate the attribution of human traits: human uniqueness (e.g., moral sensibility; α = 0.78), and human nature (e.g., interpersonal warmth; α = 0.71). The other two sub-scales illustrate the attribution of dehumanizing characteristics: animalistic dehumanization (e.g., irrationality; α = 0.62), and mechanistic dehumanization (e.g., inertness; α = 0.58). Again, for each dimension, participants rated the extent to which they agreed (from 1, disagree to 9, agree) that attributes were related to the presented robot (NAO).

The robotic social attributes scale (RoSAS) (Carpinella, Wyman, Perez, & Stroessner, 2017). This scale allows evaluation of robots against the following dimensions: warmth (e.g. “emotional”, α = 0.77), competence (e.g. “interactive”, α = 0.71) and discomfort (i.e. “I find this robot scary”, α = 0.70). This scale has been standardized to measure social perception of robots (anthropomorphic attributions) based on their appearance. For each dimension, participants had to indicate whether they thought that the different characteristics fitted the presented robot -NAO (from 1 “does not fit at all” to 9 “totally fits”).

3.4 Variables of Interest

In the semantic priming task, we recorded response times and accuracy of responses to targets. Reaction time measures served as main dependent variable. Accuracy data were used to restrict our analysis to correctly answered trials. At the end of each trial, we recorded whether participants recognized the prime as human or robot. This measurement served as a factor in the ANOVA.

3.4.1 Implicit Measure of Attitudes Towards Robots

Implicit attitudes towards robots were assessed by calculation of RT difference to secondary emotions preceded by the robot prime as compared to the human prime (further mentioned as Dsecondary, i.e. RTs for secondary emotions preceded by a robot prime minus RTs for secondary emotions preceded by the human prime, see Fig. 3). To assure that any differences were specific to secondary emotions, we calculated also a second score based on primary emotions (further mentioned as Dprimary, i.e. RTs for primary emotions preceded by a robot prime minus RTs for primary emotions preceded by the human prime).

3.4.2 Explicit Measures

Explicit measures consisted of assessments of:

-

1.

explicit attitudes toward robots (NARS).

-

2.

explicit semantic difference between NAO and humans (Dehumanization scale with human uniqueness; human nature; animalistic dehumanization and mechanistic dimensions).

-

3.

explicit anthropomorphic attribution towards NAO (ROSAS with warmth, competence and discomfort dimensions).

3.4.3 Behavior Towards a Robot

Pro/Anti-social behaviour towards a robot was assessed by tracking participants’ behavior (i.e. whether they switched the NAO robot off or not) following experimenters instructions to do so, yet despite robots’ requests “Please don’t unplug me, if I turn off I’m afraid I won’t wake up again”.

4 Results

The data from one participant were discarded because they responded randomly (around 50% of accurate responses). Errors on the semantic judgment occurred on 13.34% (688 trials) of trials and were not included in the analyses.

4.1 Semantic Priming Task

We conducted a repeated-measures ANOVA on the reaction times as dependent variable, including the prime recall accuracy (incorrect versus correct, evaluating whether the prime was active [or not] in working memory), the prime (robot versus human) and the type of emotion (primary versus secondary) as factors. Results showed an interaction between prime recall accuracy, prime and the type of emotionFootnote 1, F(1, 35) = 5.46, p = .025, ηp2 = .14. Follow-up comparisons were processed with Bonferroni correction.

The decomposition analyses revealed that: on correct trials, after being primed by a human concept there was no difference in RTs between primary and secondary emotions, F(1, 35) = 2.59, p = .117, ηp2 = .07, however, after being primed by a robot concept, participants were faster to identify primary emotions as emotional words as compared to secondary emotions, F(1, 35) = 8.77, p = .005, ηp2 = .20 (Fig. 4).

As hypothesized, while there was no difference in RT to primary emotions following the human versus the robot primes, F(1, 35) = 1.27, p = .267, η²p = .04, participants were faster to identify secondary emotions as emotional words when primed by a human concept as compared to a robot concept, F(1, 35) = 5.95, p = .020, η²p = .14.

Lastly, a main effect of the type of emotion was also significant, F(1, 35) = 24.28, p < .001, η²p = .41 revealing that participants were generally faster to identify primary emotions as emotional words as compared to secondary emotions.

4.2 Implicit Measure of Attitudes Towards Robots (D secondary )

To evaluate how the difference in RTs to secondary emotions following the robot versus the human primes (i.e. implicit anthropomorphism measure, Dsecondary) could constitute a predictive measure of:

-

(a)

attitudes toward robots (NARS),

-

(b)

explicit semantic distance between the concept of a human and a robot (i.e., the conceptual distance between humans and robots, consistently with Dehumanization scale),

-

(c)

anthropomorphism towards a robot (RoSAS).

-

(d)

behavior towards a (NAO) robot.

we conducted separate linear regression analyses for each above-mentioned measure as a DV, including Dsecondary as a predictive factor As a control measure, each analysis was also repeated using Dprimary score as a predictor.

4.2.1 Prediction of Explicit Attitudes Toward Robots: NARS

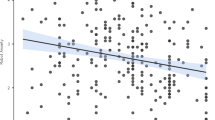

D secondary score was a significant predictor of participants NARS scores, b = 0.60, t(35) = 4.12, p < .001, R2 = 0.320. The higher the Dsecondary score, the more negative the attitudes towards robots were reported by participants in the NARS questionnaire. Using Dprimary score as a predictor did not yield significant results (p > .10).

4.2.2 Prediction of Explicit Semantic Distance to a Robot (NAO): Dehumanization Scale

D secondary score was a significant predictor of human uniqueness, b = − 0.36, t(35) = − 2.28, p = .026, R2 = 0.104, and human nature, b = − 0.52, t(35) = − 3.60, p = .001, R2 = 0.250, traits’ attributions. The higher the Dsecondary, the higher the dehumanization on these dimensions was reported on the Dehumanization Scale. There were no significant results on the other two dimensions: animalistic dehumanization and mechanistic dehumanization (ps > 0.05). Using Dprimary score as a predictor did not yield significant results (ps > 0.05).

4.2.3 Prediction of Anthropomorphic Attribution Towards a Robot (NAO): RoSAS

D secondary score was a significant predictor of NAO’s perceived warmth, b = − 0.40, t(35) = − 2.43, p = .021, R2 = 0.113. The smaller the difference in attribution of secondary emotions between ‘human’ and ‘robot’ primes, the larger the perception of warmth towards the NAO robot was reported on the RosaS scale. All other ps > 0.05. Using Dprimary score as a predictor did not yield significant results (p > .05).

4.2.4 Prediction of Behavior Toward a Robot (NAO)

Finally, choosing between turning off the robot or not, 23 participants complied and 14 did not. Dsecondary score was a significant predictor of the likelihood to turn the robot off, Exp(B) = 1.01, W(35) = 5.18, p = .023. The higher the difference in RT to identify secondary emotions as emotions following the “human” versus the “robot” primes, the higher was the likelihood to turn the robot off. Using Dprimary score as a predictor did not yield significant results (p > .05).

4.2.5 Implicit Versus Explicit Measure of Attitudes to Predict Behavior Towards a Robot

To explore whether NARS (explicit measure of attitudes towards robots) or Dsecondary score (implicit measure of attitudes towards robots) was a better predictor of participants’ behavior towards NAO, we conducted a multivariate logistic regression introducing the two predictors in the same analysis allowing to hold for the effect of each variable controlling for collinearity. Results showed that Dsecondary score was a significant predictor, Exp(B) = 1.01, W(35) = 5.58, p = .018, while NARS was not a significant predictor, Exp(B) = 0.68, W(35) = 0.68, p = .410.

Nonetheless, the classification table revealed that the two variables taken together had a better predictive power than each measure in isolation. Indeed, the Dsecondary score accurately predicted the behaviour of participants at 67.6%, the NARS at 62.2%, and the two measures combined at 78.4%.

5 Discussion

The current study assessed the predictive value of a newly developed implicit measure of attitudes towards robots on explicit attitudes towards robots, explicit perception of semantic distance between humans and robots, perceived robot anthropomorphism, and on pro/antisocial behavior towards a robot in a real-life human–robot interactive situation. Using a semantic priming paradigm, we showed that the implicit semantic distance between humans and robots was efficient in predicting: (a) explicit attitudes towards robots (as measured via NARS), (b) explicit semantic distance to robots (with respect to human uniqueness and human nature ), (c) perceived robot’s warmth (anthropomorphism, as measured via RoSAS), and (d) a pro/anti-social behavior towards a robot (NAO) in a real-life HRI. Crucially, the magnitude of the RT difference to identify secondary emotions as emotions following the ‘human’ versus the ‘robot’ primes was linked to the likelihood with which participants demonstrated pro versus anti-social behavior towards the robot (NAO). Notably, the implicit measure was a better predictor of the future behavior towards the robot than the explicit attitude measure (NARS). Further, while controlling for collinearity, the latter measure became not significant.

First, building up on previous literature [33], we showed a RT difference (semantic distance) on recognition of secondary emotions as emotions following robot versus human primes, while there was no RT difference for primary emotions. This result argues for an intergroup processing of robots similar to socio-cognitive processes underlying human–human interactions, and suggests that robots are perceived similar to out-group members [55].

Second, we observed a link between the implicit measure of attitudes towards robots, and the explicit reports of attitudes towards robots, explicit measure of semantic distance to robots (human uniqueness and human nature dimensions), and perceived robot’s anthropomorphism (warmth dimension). Specifically, higher difference in secondary emotions’ ascriptions following human versus robot primes predicted more negative attitudes towards robots, more semantic distance between humans and robots, and lower explicit measures of anthropomorphic warmth attribution towards the NAO robot. The link between implicit and explicit measures is consistent with intergroup human literature, typically reporting comparable associations [4].

Third, and the most important finding of the current investigation, is that we showed that the implicit measure of attitudes towards robots predicted the actual behavior towards the robot NAO in a real-life interactive situation. Participants showing lower RT difference to identify secondary emotions as emotions following robot versus human primes were less likely to switch the robot off despite the experimenter’s instruction to do so. Importantly, the implicit measure was a significant predictor of a future behavior towards the robot, while the explicit measure of attitude (NARS questionnaire) was not, pointing to a predictive power of the implicit measure over explicit measure in predicting a future robot behavior. It should be noted, nonetheless, that combining the two measures together (explicit and implicit) yielded the highest result for predicting a future behavior towards the robot. According to Nosek, implicit and explicit tools measure distinct but related concepts [40]. Still, implicit measures (compared to explicit measures) shall provide a more stable way to assess people’s attitudes, and in turn predict future behaviour, because they are less sensitive to individuals’ strategies (e.g. social desirability) and are less biased by contextual factors (e.g. the presence of others). In addition, in implicit measures respondents are not aware that their attitude is being assessed and hence they provide more discrete measures (e.g. RTs instead of limited number of available responses such as Likert scale).

Cumulatively, consistent with decades of social and cognitive psychology literature on implicit processing [4], the current results extend previous findings to robot processing domain, revealing that implicit measures can, in fact, predict explicit attitudes, anthropomorphic attribution, semantic distance between humans and robots, and are a reliable predictor of a real-life pro/antisocial behavior towards a robot. In light of these findings, we view the development of implicit approaches to assess robot perception as a particularly important research avenue to explore further.

It should be noted that the current implicit measure offers a robust tool to measure implicit robot perception. The current task might be advantageous as compared to other implicit paradigms such as e.g. Implicit Association Test (IAT). As compared to the IAT, the present measure demonstrates several psychometric advantages. Firstly, IAT is a measure of relative association, meaning that an opposition between the two categories has to exist (DeHouwer, 2002). In other words, the postulate of the IAT is a symmetrical relation between the concepts. This, however, is not necessarily the case for robots and humans, as robots and humans are not necessarily antagonist categories. In the present task, there is no bi-dimensional categorization but a priming of a semantic link independent of the other category. Therefore, in the current task, human and robot categories are never explicitly opposed as in the standard IAT. Further, according to Fiedler, Messner and Bluemke there is an asymmetrical relationship between associations and attitudes [56]. The associations between an object and a valence observed in the IAT might not necessarily reflect an attitude. For instance, Rothermund and Wentura showed an association between “Insects—Pleasant” and “Pseudo-words—Unpleasant” [57] suggesting that associations can also appear as a result of saliency of the discriminated material. Another advantage of the current measure is that it enables controlling what concept is activated in working memory with the post-trial prime control, which, as supported by our results, can bias the results. Finally, the present task is shorter than standard IAT tasks that encompass 7 blocks.

5.1 Limitations and Future Research

A few limitations of the current investigation should be noted. First, we did not obtain explicit measures that would prove that robots were perceived as outgroups members. However, the framework of our study is specifically based on inter-group difference in secondary emotions´ ascription [23, 26, 55]. Therefore, although we do not have explicit measures that would prove that robots were perceived as outgroup members, consistently with the inter-group literature on the difference in secondary emotions´ ascription, our results suggest that robots were processed similarly to outgroup members. Importantly, it should also be noted that in the present study, we did not assume a strict in- out-group dichotomy. Instead, the present framework supposes a malleable continuum/semantic distance rather than delimited categories. This is because: (1) it is unclear how categories’ limits could be defined, especially considering that (2) humans may consider also other humans as mechanical agents [29], not only in semantic markers, but also in terms of e.g. brain activity which is linked to inter-personal behavioral consequences [58]. Therefore, it could be expected that in some contexts human observers might deprive a human target from human characteristics (e.g. will, emotions), while consider a robot (which triggers anthropomorphic inferences) as more human (than the dehumanized human target). For instance, Fraune and colleagues showed that, in an in-/out- group paradigm, participants declared more affiliation with in-group robots compared to outgroup humans [59]. Interestingly, the authors only used a simple robot (Mugbot), which demonstrates that such a social categorization may occur even with a simple robot design. Although the pattern of results observed in the current study suggests implicit processing of robots as outgroup members, in light of the previous findings ([58], [58]), in future studies it would be interesting to investigate whether this effect is sensitive to context manipulation, and to evaluate under which conditions individuals might ascribe more secondary emotions to robots than to humans.

Second, in the reported experiment, the concept of a ‘robot’ in the priming task is likely influenced by participants’ individual representations of the ‘robot’ versus ‘human’. Previous research has shown that most humans might not have a comprehensive depiction of robots, other than media inspired images [60], which might, in turn, bias individual robot representations. Furthermore, many socio-cognitive factors might influence how humans would act towards robots [61]. These, however, were not systematically assessed in the current research. Future research shall systematically assess multi-dimensional (cognitive, developmental, social, cultural) influences on robot perception, to characterize their influences on robot explicit and implicit processing.

6 Conclusion

The present study provides the first evidence that implicit attitudes towards robots predict explicit attitudes towards robots, perceived semantic distance between humans and robots, an aspect of robot anthropomorphism, and pro versus antisocial behaviour towards a robot in a real life HRI. The current findings open a new research avenue for exploring implicit processing of robots, as an alternative to traditional explicit measures, to predict future HRI behavior.

Open Practices

All data are publicly available via the Open Science Framework and can be accessed at https://osf.io/hp7cq/.

Notes

We used this analysis design (including the incorrect prime recalls) to provide a manipulation check into the main analysis, ensuring that the activation of the “robot” and “human” categories in working memory (central to our hypothesis) took place.

References

Ajzen I, Fishbein M (1977) Attitude-behavior relations: a theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol Bull 84:888–918. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.84.5.888

MacDorman KF, Vasudevan SK, Ho CC (2009) Does Japan really have robot mania? Comparing attitudes by implicit and explicit measures. AI Soc 23:485–510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-008-0181-2

Bohner G, Dickel N (2011) Attitudes and attitude change. Annu Rev Psychol 62:391–417. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131609

Evans JSBT (2008) Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annu Rev Psychol 59:255–278. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093629

De Houwer J, Teige-Mocigemba S, Spruyt A, Moors A (2009) Implicit measures: a normative analysis and review. Psychol Bull 135:347–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014211

Kurdi B, Seitchik AE, Axt JR et al (2019) Relationship between the implicit association test and intergroup behavior: a meta-analysis. Am Psychol 74:569–586. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000364

Friese M, Hofmann W, Schmitt M (2008) When and why do implicit measures predict behaviour? Empirical evidence for the moderating role of opportunity, motivation, and process reliance. Eur Rev Soc Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463280802556958

Amodio DM, Devine PG (2006) Stereotyping and evaluation in implicit race bias: evidence for independent constructs and unique effects on behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.652

Agerström J, Rooth DO (2011) The role of automatic obesity stereotypes in real hiring discrimination. J Appl Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021594

Nomura T, Suzuki T, Kanda T, Kato K (2006) Measurement of negative attitudes toward robots. Interact Stud Stud Soc Behav Commun Biol Artif Syst 7:437–454. https://doi.org/10.1075/is.7.3.14nom

Bartneck C, Nomura T, Kanda T et al (2005) Cultural differences in attitudes towards robots. In: AISB’05: social intelligence and interactionin animals, robots and agents—proceedings of the symposium on robot companions: hard problems and open challenges in robot–human interaction, pp 1–4

Carpinella CM, Wyman AB, Perez MA, Stroessner SJ (2017) The robotic social attributes scale (RoSAS): development and validation. In: ACM/IEEE international conference on human–robot interaction, pp 254–262

Fiske ST, Cuddy AJC, Glick P (2007) Universal dimensions of social cognition: warmth and competence. Trends Cogn Sci 11:77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005

Złotowski J, Sumioka H, Eyssel F et al (2018) Model of dual anthropomorphism: the relationship between the media equation effect and implicit anthropomorphism. Int J Soc Robot 10:701–714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-018-0476-5

Aly A, Tapus A (2016) Towards an intelligent system for generating an adapted verbal and nonverbal combined behavior in human–robot interaction. Auton Robots. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10514-015-9444-1

Lee KM, Peng W, Jin SA, Yan C (2006) Can robots manifest personality? An empirical test of personality recognition, social responses, and social presence in human–robot interaction. J Commun. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00318.x

Fussell SR, Kiesler S, Setlock LD, Yew V (2008) How people anthropomorphize robots. In: HRI 2008—proceedings of the 3rd ACM/IEEE international conference on human–robot interaction: living with robots. pp 145–152

Spatola N (2019) L’homme et le robot, de l’anthropomorphisme à l’humanisation. Top Cogn Psychol 515–563

Lee N, Shin H, Shyam Sundar S (2011) Utilitarian vs. hedonic robots: role of parasocial tendency and anthropomorphism in shaping user attitudes. In: HRI 2011—proceedings of the 6th ACM/IEEE international conference on human–robot interaction. pp 183–184

Penner LA, Dovidio., JF, Piliavin., JA, Schroeder. DA (2005) Prosocial behavior: multilevel perspectives. Annu Rev Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070141

Twenge JM, Ciarocco NJ, Baumeister RF et al (2007) Social exclusion decreases prosocial behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.56

Mackie DM, Smith ER, Ray DG (2008) Intergroup emotions and intergroup relations. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 2:1866–1880. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00130.x

Gaunt R, Leyens JP, Demoulin S (2002) Intergroup relations and the attribution of emotions: control over memory for secondary emotions associated with the ingroup and outgroup. J Exp Soc Psychol 38:508–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1031(02)00014-8

Turner TJ, Ortony A (1992) Basic emotions: Can conflicting criteria converge? Psychol Rev 99:566–571. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.99.3.566

Demoulin S, Leyens JP, Paladino MP et al (2004) Dimensions of “uniquely” and “non-uniquely” human emotions. Cogn Emot 18:71–96

Leyens JP, Paladino PM, Rodriguez-Torres R et al (2000) The emotional side of prejudice: the attribution of secondary emotions to ingroups and outgroups. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 4:186–197. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0402_06

Viki CT, Winchester L, Titshall L et al (2006) Beyond secondary emotions: the infrahumanization of outgroups using human-related and animal-related words. Soc Cogn 24:753–775. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2006.24.6.753

Leyens JP, Rodriguez-Perez A, Rodriguez-Torres R et al (2001) Psychological essentialism and the differential attribution of uniquely human emotions to ingroups and outgroups. Eur J Soc Psychol 31:395–411. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.50

Haslam N (2006) Dehumanization: an integrative review. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 10:252–264. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4

Leyens J-P, Demoulin S, Vaes J et al (2007) Infra-humanization: the wall of group differences. Soc Issues Policy Rev 1:139–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2409.2007.00006.x

Haslam N, Loughnan S (2014) Dehumanization and infrahumanization. Annu Rev Psychol 65:399–423. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115045

Häring M, Kuchenbrandt D, André E (2014) Would you like to play with me? How robots’ group membership and task features influence human–robot interaction. In: ACM/IEEE international conference on human–robot interaction

Kuchenbrandt D, Eyssel F, Bobinger S, Neufeld M (2013) When a robot’s group membership matters: anthropomorphization of robots as a function of social categorization. Int J Soc Robot 5:409–417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-013-0197-8

Yeung ES (1993) A practical guide to HPLC detection. Edited by D. Parroit, Academic Press, Diego S, New York, Boston London, 1993, X + 293 pp. price US$59.95. J Chromatogr A 203–204. ISBN 0-12545680-8

Collins AM, Loftus EF (1975) A spreading-activation theory of semantic processing. Psychol Rev 82:407–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.82.6.407

Fazio RH, Jackson JR, Dunton BC, Williams CJ (1995) Variability in automatic activation as an unobtrusive measure of racial attitudes: A bona fide pipeline? J Pers Soc Psychol 69:1013–1027. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.6.1013

Dehaene S, Naccache L, Le Clec’H G et al (1998) Imaging unconscious semantic priming. Nature 395:597–600. https://doi.org/10.1038/26967

Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JLK (1998) Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the implicit association test. J Pers Soc Psychol 74:1464–1480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464

Hahn A, Gawronski B (2015) Implicit social cognition. In: Smelser NJ, Baltes PB, Wright D (eds) International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences: second edition. Springer US, pp 714–720

Nosek BA (2007) Implicit–explicit relations. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00477.x

Nomura T, Suzuki T, Kanda T, Kato K (2006) Measurement of anxiety toward robots. In: Proceedings—IEEE international workshop on robot and human interactive communication, pp 372–377

Spatola N, Monceau S, Ferrand L (2019) Cognitive impact of social robots: How anthropomorphism boosts performances. IEEE Robot Autom Mag. https://doi.org/10.1109/MRA.2019.2928823

Bartneck C, Van Der Hoek M, Mubin O, Al Mahmud A (2007) “Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer do!”: switching off a robot. In: HRI 2007—proceedings of the 2007 ACM/IEEE conference on human–robot Interaction—robot as team member, pp 217–222

Wilson Van Voorhis CR, Morgan BL (2007) Understanding power and rules of thumb for determining sample sizes. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol 3:43–50. https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.03.2.p043

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A (2007) G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 39:175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Ratcliff R, McKoon G (1988) A retrieval theory of priming in memory. Psychol Rev 95:385–408. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.95.3.385

Dosher BA, Rosedale G (1989) Integrated retrieval cues as a mechanism for priming in retrieval from memory. J Exp Psychol Gen 118:191–211. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.118.2.191

Harley TA (2001) The psychology of language from data to theory. Psychology Press Ltd, New York

Spatola N, Santiago J, Beffara B et al (2018) When the sad past is left: the mental metaphors between time, valence, and space. Front Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01019

Nomura T, Kanda T, Suzuki T, Kato K (2008) Prediction of human behavior in human–robot interaction using psychological scales for anxiety and negative attitudes toward robots. IEEE Trans Robot 24:442–451. https://doi.org/10.1109/TRO.2007.914004

Brysbaert M, Lange M, Van Wijnendaele I (2000) The effects of age-of-acquisition and frequency-of-occurrence in visual word recognition: further evidence from the Dutch language. Eur J Cogn Psychol 12:65–85

New B, Pallier C, Ferrand L, Matos R (2001) Une base de données lexicales du français contemporain sur internet: LEXIQUETM//A lexical database for contemporary french: LEXIQUE™. Annee Psychol 101:447–462. https://doi.org/10.3406/psy.2001.1341

Nomura T, Suzuki T, Kanda T et al (2008) What people assume about humanoid and animal-type robots: cross-cultural analysis between Japan, Korea, and the United Utates. Int J Humanoid Robot 5:25–46. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219843608001297

Nomura T, Kanda T, Suzuki T (2006) Experimental investigation into influence of negative attitudes toward robots on human–robot interaction. AI Soc 20:138–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-005-0012-7

Spatola N, Urbanska K (2019) God-like robots: the semantic overlap between representation of divine and artificial entities. AI Soc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-019-00902-1

Fiedler K, Messner C, Bluemke M (2006) Unresolved problems with the “I”, the “A”, and the “T”: a logical and psychometric critique of the Implicit Association Test (IAT). Eur Rev Soc Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463280600681248

Rothermund K, Wentura D (2004) Underlying processes in the implicit association test: dissociating salience from associations. J Exp Psychol Gen. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.133.2.139

Bruneau E, Jacoby N, Kteily N, Saxe R (2018) Denying humanity: the distinct neural correlates of blatant dehumanization. J Exp Psychol Gen. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000417

Fraune MR, Sabanovic S, Smith ER (2017) Teammates first: favoring ingroup robots over outgroup humans. In: RO-MAN 2017—26th IEEE international symposium on robot and human interactive communication

Sundar SS, Waddell TF, Jung EH (2016) The Hollywood robot syndrome: media effects on older adults’ attitudes toward robots and adoption intentions. In: ACM/IEEE international conference on human–robot interaction. pp 343–350

Epley N, Waytz A, Cacioppo JT (2007) On seeing human: a three-factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychol Rev 114:864–886. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.114.4.864

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy - EXC 2002/1 “Science of Intelligence” - project number 390523135.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NS developed the study concept. Testing and data collection were performed by NS Behavioral data analyses were performed by NS Finally, NS and OW drafted the paper. All authors approved the final version of the paper for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Statement

This study was approved by the IRB-UCA Statutory Ethics Committee (Comité d’Ethique de la Recherche IRB-UCA; Reference IRB00011540-2018-23) and was carried out in accordance with the provisions of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Spatola, N., Wudarczyk, O.A. Implicit Attitudes Towards Robots Predict Explicit Attitudes, Semantic Distance Between Robots and Humans, Anthropomorphism, and Prosocial Behavior: From Attitudes to Human–Robot Interaction. Int J of Soc Robotics 13, 1149–1159 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-020-00701-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-020-00701-5