Abstract

Triple gallbladder represents a rare congenital anatomical abnormality that can be a diagnostic challenge in reason to its rarity and consequential difficulties with diagnosis and identification. A systematic review of all published literature between 1958 and 2022 was performed. We identified 20 previous studies that provided 20 cases of triple gallbladder; our case was also included in the analysis, making a total of 21 patients. All patients underwent on diagnostic imaging examinations. After 1985, 9 patients underwent US examination which allowed prompt recognition of triple gallbladder in 2 patients only. CT was performed in 3 patients and allowed the correct diagnosis in a case. In 4 patients, was performed MRCP which allowed the correct diagnosis of triple gallbladder in all patients. Preoperative imaging allows the recognition of triple gallbladder in 9 of 21 patients (43%); in 12 patients (57%) the diagnosis was intraoperative. On patients considered, 16/21 underwent cholecystectomy. In 15 cases, the excised gallbladders were submitted for histopathological characterization with detection of metaplasia of the mucosa in 3 patients, while papillary adenocarcinoma was found in one. Imaging plays a key role in the identification of the anatomical variants of gallbladder, especially triple gallbladder, as modern imaging techniques allow a detailed assessment of the course of the biliary tract for a correct preoperative diagnosis. It is also crucial to be aware of the association between this condition and the metaplasia phenomena with the development of adenocarcinoma, as this may influence the patient’s course of treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Triple gallbladder, also called vesica fellea triplex, was first reported by Huber in 1752 during an autopsy [1]; it is an uncommon congenital and often undetected abnormality of the biliary system and, up to now, only 20 cases have been reported in the literature. Therefore, the identification of some congenital gallbladder anomalies, due to their rarity, might represent a significant clinical challenge [2]. As a matter of fact, most of the extrahepatic biliary system abnormalities come to medical attention only when symptoms, that are mainly related to cholelithiasis and cholecystitis, occur.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the cross-sectional imaging findings in patients with triple gallbladder through a literature review as it is associated with an increased rate of gallbladder metaplasia, dysplasia, and adenocarcinoma: for these reasons, the prompt identification of this anatomical variant is crucial.

Case report

A 56-year-old female patient reported acute abdominal pain in the right hypochondrium and mild nausea after a large meal; the pain spontaneously regressed in about 24 h after onset. The patient had no clinical history of either biliary colic or biliary tract disease, never had any kind of abdominal surgery; no comorbidity were reported.

Blood tests performed 7 days after the acute episode revealed an increase in total (2.56 mg/dl) and indirect bilirubin (0.65 mg/dl); serum tumor markers (CEA and CA 19.9) were negative.

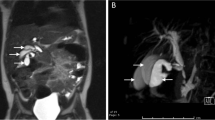

The patient underwent ultrasound (US) examination, performed with a high-definition multiband convex probe. The US showed three closely adjacent gallbladders in the cholecystic fossa. One of the gallbladders was hypo-distended, with diffuse thickened and irregular hyperechogenic walls with focal thickening at the fundus (Fig. 1). No dilation of intra- and extrahepatic biliary system was detected. However, ultrasonographic examination did not allow a detailed study of the anatomy of the cystic ducts and their relationship with the extrahepatic biliary tree, neither of all the three gallbladders: for these reasons, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was performed.

The MR examination was performed using a high-field magnetic scanner (1.5 Tesla) with axial T2-weighted (w) and T2w-SPAIR sequences, T1w-DUAL FFE sequence, diffusion weighted imaging and completed with MRCP study obtained with radial, volumetric and gradient and spin echo (GRaSE) sequences.

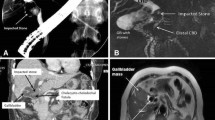

The study confirmed the presence of three distinct gallbladders located in the cystic fossa (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7):

A Coronal balanced turbo-field-echo (BTFE) sequence showed three different gallbladder one of which with irregular wall. B Anterior view of 3D-MIP magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) with gradient and spin echo (GRASE) technique; to note the anterior gallbladder with irregular wall, fundal thickness (arrow) and higher T2 signal than two others. C Posterior view of 3D-MIP magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) with gradient and spin echo (GRASE) technique; to note the confluence of the two posterior cystic ducts into a single duct (*)

3D volume rendering reconstruction showing three different gallbladders one of which with irregular wall. RIA right-infero-anterior; SRP supero-right-posterior, ILA infero-left-anterior, LSP left-supero-posterior; IRP infero-right-posterior, RAS right-antero-superior, SLA supero-left-anterior, LPI left-postero-inferior

A Transverse T2 showing three distinct gallbladders (numbers 1, 2 and 3) [123]. B Infero-lateral view of 3D-MIP magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) with gradient and spin echo (GRASE) technique; to note the fundus of the three distinct gallbladders [123], the anterior with fundal thickness (*) and higher T2 signal than two others

Anterior view of 3D-MIP magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) with gradient and spin echo (GRASE) technique; to note the anterior gallbladder with irregular wall, fundal thickness (arrow) and higher T2 signal than two others and the confluence of the two posterior cystic ducts into a single duct (*)

- the most anterior gallbladder had a more hyperintense endoluminal T2 signal and was characterized by irregular walls and multiple parietal thickenings with polypoid-like appearance. The largest wall thickening was at the fundus (6 mm). The cystic duct arising from this gallbladder showed mild ectasia (5 mm) and confluence on the posterior wall of the middle third of the choledochal duct (Figs. 6, 7).

- the two posterior gallbladders had regular walls and their respective cystic ducts converged into a single duct which joined the choledochal duct at the level of the postero-medial wall, just below the insertion of the cystic duct of the anterior gallbladder (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7).

According to the Harlaftis classification [3], the presented triple gallbladders had Y + H morphology (Fig. 4).

MRCP showed a focal filling defect in the intrapancreatic choledochal duct immediately downstream the confluence of the cystic ducts, with ectasia of the upstream segment (7 mm); the pre-papillary segment of the choledochal duct showed a maximum diameter of 5 mm with no evidence of endoluminal signal abnormalities (Figs. 2, 7).

Patient underwent to surgical examination during which she was informed about the clinical risks associated with this rare condition and even though laparoscopic cholecystectomy was proposed to remove the triple gallbladder, and the patient refused surgery.

Methods

We performed a literature search for case description of triple gallbladder in humans published up to September 2022, using the keywords “triple cholecyst”, “triple gallbladder”, “multiple cholecysts” and “multiple gallbladder” without additional filters. Eligible articles were fully reviewed for compliance with the research objectives and adequacy of data. Studies reporting a clear description of the triple gallbladder found during radiological examinations or following cholecystectomy surgery were considered eligible. In addition, we included the present case report. Radiological features and clinical data were collected and analyzed by descriptive statistics.

The study was conducted according to local ethical standards and Helsinki Declaration’s principles.

Results

From the literature review, we identified 20 previous studies that provided 20 cases of triple gallbladder; our case of triple gallbladder was also included in the analysis, making a total of 21 patients with triple gallbladder. The clinical and anamnestic characteristics of the patients, radiological examinations, laboratory tests, surgeries performed, and histopathological findings are summarized in Table 1.

First case of triple gallbladder was reported by Boni in 1958 [4]. The triple gallbladder is more common in women (12 women and 9 men), with a female/male ratio of 1.33; the mean age at diagnosis was 34 years, specifically 36 years in women and 32 years in men.

The clinical manifestations of triple gallbladder are related to non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms: most patients (20/21 patients—95%) had at least one episode of abdominal pain before diagnosis. The abdominal pain manifested either as a single episode of biliary colic or as repeated self-limited episodes occurring over a variable period of weeks, months or even years.

Only in one patient the diagnosis of triple gallbladder occurred without abdominal pain, and it was found incidentally through radiological examinations performed following an episode of hematemesis [5].

In addition to abdominal pain, 9/21 (43%) patients presented with nausea and/or vomiting, 4/21 (19%) patients presented fever, and 3/21 (14%) had a clinical history of cholelithiasis or choledocholithiasis.

In 13 patients, blood chemistry tests were performed after the onset of symptoms; in particular, we evaluated indices of liver function (aspartate aminotransferase-AST, alanine aminotransferase-ALT, total bilirubin), cholestasis (Gamma-glutamyl Transferase-GGT, Alkaline Phosphatase-ALP, direct bilirubin) and leukocytosis as the main inflammatory index. Among these 13 patients, 4 had normal blood tests; in the remaining 9 patients, cholestasis and leukocytosis indices were abnormal. 6 patients (46%) had at least one increased cholestasis index value and 4 patients (31%) had leukocytosis. An increase in liver function indices was detected in only in 3 patients (23%).

All patients underwent further diagnostic investigation by imaging examinations. Specifically, all the 11 patients reported between 1958 and 1985 underwent cholangiography: this exam allowed the recognition of the triple gallbladder in 5 cases while in 3 cases revealed two gallbladders and in the last 3 cases it was not diagnostic. However, a correct depiction of the extrahepatic biliary anatomy was achieved in 3 patients only.

In the cases published after 1985, 9 patients underwent US as the first-level imaging examination: US allowed prompt recognition of triple gallbladder in 2 patients only, while in 4 patients, it was wrongly identified a duplicate gallbladder. Moreover, US rarely allows correct biliary tree anatomy depiction.

CT was performed only in 3 patients and allowed the correct diagnosis of triple gallbladder in a case.

In 4 patients, the study of the biliary tract was performed by MRCP which allowed the correct diagnosis of triple gallbladder in all patients, even though in a single patient, it gave incomplete information about the anatomy of the biliary tree.

ERCP was performed in only in 2 patients, and in both cases, it was non-diagnostic.

Considering the available data, preoperative imaging allows the recognition of triple gallbladder in 9 of 21 patients (43%) only; in the remaining 12 patients (57%), the diagnosis was intraoperative.

All reported cases of triple gallbladder were classified according to the anatomy of the cystic ducts [3], specifically the most frequently encountered anatomical variant was type I (11/20 patients, 55%) followed by type II (6/20 patients, 30%) and type III (3/20 patient 15%).

Only for a patient, the anatomy of cystic ducts was not defined and for this reason, it has not been reported [6].

Of the total 21 patients considered, 16 underwent to cholecystectomy. In 15 cases, the surgical samples of the excised gallbladder were submitted for histopathological characterization and the most common histologic finding was chronic cholecystitis (11/15 patients, 73%). In 2 patients, the walls of the excised gallbladder had necrotic and hemorrhagic features. Only a patient had no histological changes of gallbladder [7].

Metaplasia of the gallbladder mucosa was found in 3 patients [8,9,10], of which 2 had duodenal mucosa [9, 10] and one had gastric mucosa and ossicular cells [8].

Dysplastic mucosa with papillary adenocarcinoma was found in one patient [11]. The presence of endoluminal lithiasis was found in 9 patients (43%).

Discussion

During the 4th week of gestation, hepatobiliary and pancreatic organogenesis begins from the endodermal bud originating from the anterior intestine [12]; specifically, its upper segment gives rise to the liver and intrahepatic bile ducts and its lower segment to the gallbladder, cystic duct, and common bile duct [13]. Between the 4th and 5th week of gestation, the gallbladder primordium begins to form, which will give rise to the gallbladder and cystic duct: interruption or alteration of the development process at this stage may result in malformations of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts [12]. In 1926, Boyden hypothesized that multiple gallbladders represented an outgrowth of a secondary vesicle from a portion of the bile duct system after the formation of the definitive gallbladder [14]. In the human embryo, this small cellular opening, called the rudimentary bile duct, usually regresses, and disappears [15]; however, the failure of the rudimentary bile ducts to regress can lead to the formation of extroversions along the biliary system, and when it occurs along the extrahepatic pathways, it can result in the development of accessory gallbladders [8].

Depending on the location of these accessory sacs, different anatomical relationships between gallbladders, cystic ducts and common hepatic duct will take place: if the buds that give rise to the accessory gallbladders originate from the common hepatic duct, the gallbladders will have independent and separate cystic ducts; on the other hand, if the sacs originate from a cystic duct there will be gallbladders with a common cystic duct draining into the common hepatic duct [1].

In 1977, Harlaftis et al. proposed an anatomical classification of multiple gallbladder based on the embryogenetic mechanism [3]:

-

-type I consists of a double gallbladder with more or less separate cystic ducts jointly discharging into the common hepatic duct;

-

-type II consists of a double gallbladder with two independent cystic ducts discharging separately into the biliary tree; in this case, the accessory gallbladder may reach the common hepatic duct (ductular type) or an intrahepatic bile duct (trabecular type);

-

-type III includes gallbladder with anatomical anomalies that do not fit the previous two groups.

Based on the number and morphology of the cystic ducts, three different types of triple gallbladder have been identified by Alicioglu [16]:

-

a)

the first type is characterized by the presence of three gallbladders each with its own independent cystic duct hat drains separately into the bile duct;

-

b)

the second type is characterized by the presence of two gallbladders with a common cystic duct draining into the common bile duct and a third gallbladder with independent cystic duct;

-

c)

the third type is characterized by the presence of three gallbladders sharing a single cystic duct.

From our analysis, the most common type of triple gallbladder was type I (55%) followed by type II (30%) and finally type III, the most rarely encountered variant (15%).

Multiple gallbladder is a very uncommon condition and, usually, its clinical presentation is non-specific [2, 16]. Colic abdominal pain is the most commonly reported symptom and it is related to cholecystitis and cholelithiasis [13]. Accessory gallbladders may be found incidentally in asymptomatic patients during a routine radiological examination [16].

Preoperative diagnosis of the triple gallbladder condition is crucial, as it allows proper planning of surgery and consequently also a reduction of possible intra- and post-operative complications.

Until 1979, preoperative imaging of the biliary tract was performed by oral or intravenous cholecystography, fat meal studies and conventional tomography. Currently, preoperative imaging uses high-resolution techniques such as US, spiral or multilayer CT, MRCP, and ERCP.

The most frequently performed first-level examination in the case of patients with colic symptoms related to gallbladder is US, as it is highly available and low cost [16]. However, US is an operator-dependent imaging modality and has a low sensitivity (65%), so this anatomical variation could be missed or misdiagnosed [2, 13].

Both US and CT are able to assess the anatomical features of the gallbladder such as number, wall thickness and presence of endoluminal lithiasis, although they may not depict the exact anatomy of the biliary tree [16].

Therefore, further investigations are recommended. MRCP allows a non-invasive study of the anatomy of the biliary system and its abnormalities, accurately describing the number, the position of cystic ducts and their relationship to the common bile duct [13, 17].

ERCP allows detailed assessment of the anatomy of the biliary system, but it is an invasive method that requires general anesthesia, exposes patients to radiation and it could be associated with the development of serious complications [2].

To now, MRCP has proven to be much more sensitive than ERCP, with a sensitivity of about 97% in identifying multiple gallbladder condition [13].

Total cholecystectomy with removal of all gallbladders is the appropriate treatment for symptomatic gallbladder triplication. The literature suggests that benefits from removing of all gallbladders are crucial once surgery is decided. Several studies have been reported describing the need for a second operation because symptoms were not relieved after the first cholecystectomy [18].

Prophylactic surgery is not recommended for incidentally discovered asymptomatic triplication gallbladder, but radiological follow-up is fundamental to early diagnose a possible development of biliary dysplasia or cancer.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is performed in most cases, but open approach is preferred in case of the high insertion of the cystic ducts, previous abdominal open surgery, and poor experience in laparoscopic surgery [19].

Preoperative imaging study of anatomical variants is essential for a safe surgery. The surgeon should know, preoperatively, the shape and location of gallbladders, abnormalities of the cystic artery and cystic ducts, to avoid important surgical complications, such as iatrogenic bile duct injuries and hepatic vascular injuries.

In most cases, patients with symptomatic multiple gallbladders underwent cholecystectomy.

Histopathological examination of the 15 patients who underwent surgery showed chronic cholecystitis in 9/15 patients (60%) and a cholelithiasis in 12/15 patients (80%). Only one case showed a condition of acute cholecystitis at the histopathological evaluation [20].

Moreover, the abnormal anatomy of the extrahepatic biliary outflow tracts can lead to biliary stasis and thus a predisposition to the formation of endoluminal lithiasis giving rise to a condition of chronic cholecystitis, which is a major risk factors for the occurrence of epithelial metaplasia and the development of gallbladder carcinoma [21, 22].

In fact, consistent with the literature reports [13], the triple gallbladder condition was associated with duodenal metaplasia in 2/15 cases (13%) [9, 10], with gastric metaplasia in 1/15 case (6.5%) [8] and with papillary adenocarcinoma in 1/15 case (6.5%) [11].

In our analysis, intestinal metaplasia was found in 2 cases [9, 10], both associated with a chronic cholecystitis condition, and in one case [9], associated with endoluminal lithiasis.

It is, therefore, very important to diagnose chronic cholecystitis in those anomalies as early diagnosis allows early intervention and prevents tumor development.

This represents a very important risk factor because although it is a very common pathological condition, the incidence of finding dysplasia in gallbladders removed for stones is 13.5%, and of these 3.5% have carcinoma in situ [23].

This condition, depending on both genetic and acquired risk factors [23], can be driven by a condition of gallbladder hypomotility and bile stasis [24].

Intestinal metaplasia represents a frequent finding in almost the 90% of gallbladders with chronic inflammation; this condition has a close relationship with gallstones and wall inflammation which brings to a local chronic response that drives to evolution in focal dysplasia and evolution in gallbladder adenocarcinoma in 3.5% of cases [25].

Conclusion

Surgeons and radiologists should be aware of the existence of the triple gallbladder condition and the most appropriate imaging methods for proper evaluation of this condition.

Imaging plays a key role in the identification of the anatomical variants of gallbladder, especially triple gallbladder, as modern imaging techniques allow a detailed assessment of the course of the biliary tract for a correct preoperative diagnosis. This allows the surgical procedure to be planned appropriately to reduce intraoperative risk and patient morbidity.

It is also crucial to be aware of the association between this condition and the phenomena of gastric and duodenal metaplasia and with the development of adenocarcinoma, as this may influence the patient’s course of treatment.

References

Khadim MT, Ijaz A, Hassan U, et al. Triple gallbladder: a rare entity. Amer J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1861–2.

Vezakis A, Pantiora E, Giannoulopoulos D, et al. A duplicated gallbladder in a patient presenting with acute cholangitis a case study and a literature review. Ann Hepatol. 2019;1:240.

Harlaftis N, Gray SW, Skandalakis JE. Multiple gallbladders. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1977;145:928.

Boni R. Triple gallbladder and calcareous bile. Radiologia Medica. 1958;44:833–44.

Kurzweg FT, Cole PA. Triplication of the gallbladder: review of literature and report of a case. Amer Surg. 1979;45:410.

Nanthakumaran S, King PM, Sinclair TS. Laparoscopic excision of a triple gallbladder. Surg endoscopy. 2003;17:1323.

Barnes S, Nagar H, Levine C, et al. Triple gallbladder: Preoperative sonographic diagnosis. J Ultras Med. 2004;23:1299.

Ott L, O’Neill J, Cameron D, et al. Triple gallbladder with heterotopic gastric mucosa: a case report. BMC Pediatr. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03122-7.

Kelly A. Triple gall bladder: a case of double gall bladder with associated anomalous gall bladder. Med J Aust. 1959;1:124.

Casey EW. Triple gall bladder. Australas Radiol. 1958;2:98.

Roeder WJ, Mersheimer WL, Kazarian KK. Triplication of the gallbladder with cholecystitis, cholelithiasis, and papillary adenocarcinoma. Amer J Surg. 1971;121:746.

Chen X, Yi B. Triple gallbladder. J Pediatr. 2022;247:173–4.

Darnis B, Mohkam K, Cauchy F, et al. A systematic review of the anatomical findings of multiple gallbladders. HPB. 2018;20:985.

Boyden E. The accessory gall-bladder– an embryological and comparative study of aberrant biliary vesicles occurring in man and the domestic mammals. Amer J Anat. 1926;38:177–231.

Foster DR. Triple gall bladder. Brit. J Radiol. 1981;54:817.

Alicioglu B. An incidental case of triple gallbladder. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:13.

Morimoto M, Mori N. A Calcified Gallbladder. New Engl J Med. 2020;383:86.

Gigot JF, Van Beers B, Goncette L, et al. Laparoscopic treatment of gallbladder duplication: A plea for removal of both gallbladders. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:479.

Causey MW, Miller S, Fernelius CA, et al. Gallbladder duplication: evaluation, treatment, and classification. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;44:443.

Aroca Ruiz-Funes JM, Martinez LA. Vesícula biliar triple. Rev Esp Enferm Apar Dig. 1969;54:968.

Sharma A, Sharma KL, Gupta A, et al. Gallbladder cancer epidemiology, pathogenesis and molecular genetics: Recent update. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:2978.

Bojan A, Foia L, Vladeanu M, et al. Understanding the mechanisms of gallbladder lesions: A systematic review. Exp Ther Med. 2022;24:1–4.

Lazcano-Ponce EC, Miquel JF, Munoz N, et al. Epidemiology and Molecular Pathology of Gallbladder Cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51:349.

Apstein MD, Carey MC. Pathogenesis of cholesterol gallstones: A parsimonious hypothesis. Europ J Clin Invest. 1996;26:343.

Duarte I, Llanos O, Domke H, et al. Metaplasia and precursor lesions of gallbladder carcinoma Frequency, distribution, and probability of detection in routine histologic samples. Cancer. 1993;72:1878.

Copeland-Halperin LR, Kapoor K, Piper JB. Complicated triple gallbladder: Clinical presentation and surgical approach. BMJ Case Rep. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2016-215901.

Mottin CC, Toneto MG, Padoin AV. Laparoscopic triple cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2004;14:163.

Schroeder C, Draper KR. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for triple gallbladder. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1322.

Gruk M, Wyciślak J, Muc J, et al. Triple gallbladder as a rare development anomaly of the biliary tract. Wiad Lek. 1985;38:140–2.

Ross RJ, Sachs MD. Triplication of the gallbladder. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1968;104:656.

Hause WA. Triplication of gallbladder. AMA Arch Surg. 1959;104:656.

Skielboe B. Anomalies of the gallbladder: vesica fellea triplex; report of a case. Am J Clin Pathol. 1958;1:4.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Roma Tor Vergata within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Picchi, E., Leomanni, P., Dell’Olio, V.B. et al. Triple gallbladder: radiological review. Clin J Gastroenterol 16, 629–640 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-023-01829-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-023-01829-3