Abstract

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComa) are rare mesenchymal neoplasms that arise from soft tissue of various organs such as the stomach, intestines, and lungs. We report a rare case of a primary PEComa of the liver and its characteristics on contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in a 51-year-old female patient with an incidental finding of a hypoechoic liver lesion with peripheral hypervascularization on Doppler ultrasound. CEUS showed homogenous hypervascularity in the arterial phase that was consistent in the portal phase. In the late phase, a central washout phenomenon was evident. Histopathologic findings on sonographic biopsy of the lesion revealed a mesenchymal tumor with positivity for melanocytic markers Human Melanin Black-45 (HMB45) and Melan-A consistent with a PEComa. Despite the absence of high-risk features for malignancy, surgical resection was recommended due to the uncertain malignant potential of PEComas. The patient refused the operation and preferred sonographic follow-up; the lesion was stable over a period of 2 years. CEUS can provide valuable information regarding PEComa. After histological confirmation, the choice between resection and a watchful waiting must be made on individual basis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

PEComas are rare mesenchymal tumors that histologically present as a composite of epithelioid or spindle-shaped mesenchymal cells that immunohistochemically show a characteristic concomitant expression of melanocytic Human Melanin Black-45 (HMB45) and Melan-A and smooth muscle markers (actin and desmin) [1, 2].

For the most part, PEComas affect women with predilection for the uterus [2]. However, PEComas can also occur in other organs such as the stomach, intestine, and lungs [3]. Hepatic PEComas have been described in only a few dozen cases [2, 4]. Hepatic PEComas are often discovered incidentally because of their mostly asymptomatic course [2, 4].

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) is of great importance for further differentiation of incidentally detected focal liver lesions [5]. However, the peculiarities of PEComas on CEUS are described in only five reports, whereby CEUS cannot provide certainty in diagnosis and histologic confirmation remains essential [4, 6,7,8,9]. The present case report describes the CEUS pattern of another histologically confirmed PEComa.

Case report

A 51-year-old Caucasian woman of normal weight (167 cm, 68 kg) with refractory arterial hypertension underwent a sonographic examination to exclude renal artery stenosis at our ultrasound unit. As an accidental finding, a 2 cm sized focal solid hypoechoic lesion in the right lobe of an otherwise homogenous liver was detected (Fig. 1A). The sonographic findings of the remaining abdominal organs were unremarkable and renal artery stenosis could be excluded.

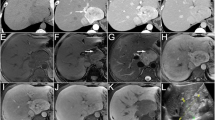

(A) B-mode ultrasound of a 51-year-old asymptomatic patient with hepatic PEComa shows a hypoechoic lesion in segment V of an otherwise unremarkable liver. (B) On color Doppler ultrasound peripheral flow signals were seen. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound of the liver in a patient with proven PEComa (C–E). The lesion shows a marked homogeneous enhancement 28 s after administration of SonoVue® (C). In the portal phase, an isoenhancement of the lesion (arrows) persists (D). In the late phase, mild central washout with a persistent rim enhancement of the lesion (arrows) is recognizable (E). Computed tomography (courtesy of Professor Dr Mahnken, Department of Radiology, University Hospital Marburg) shows a hepatic PEComa with strongly accentuated rim in the arterial phase (F)

At the time of presentation, the patient was asymptomatic without any complaints related to her liver lesion. Fever, night sweats, weight loss, or other vegetative symptoms were denied. The patient had no relevant previous medical history that could indicate a particular nature or origin of the liver lesion. The patient’s physical examination and the laboratory workup including liver enzymes and blood count were inconspicuous.

The hypoechoic liver lesion showed a peripheral flow signal on color Doppler sonography (CDS) (Fig. 1B). CEUS with the ultrasound contrast media SonoVue® (Bracco S.p.A., Milan, Italy) was performed for further evaluation. In the arterial phase, a marked hyperenhancement was seen with an isoenhancement in the portal venous phase and a light wash out in the parenchymal phase (Fig. 1C–E). A diagnosis of a hepatocellular adenoma (HCA) was initially suspected, and for further differentiation, an ultrasound-guided biopsy was performed.

The histological examination revealed a mesenchymal tumor composed of spindle cells with a marker profile consistent with a PEComa (Fig. 2). Immunohistochemical staining showed positivity for smooth muscle actin, HMB45 and Melan-A in the tumor cells, whereas the adjacent liver tissue was negative for HMB45 and Melan-A (Fig. 2D, E). No high-risk features such as marked nuclear atypia, increased mitotic activity, necrosis, infiltrative growth, or vascular invasion were present, indicating a benign nature of the lesion [4, 10].

Core needle biopsy of a 2 cm suspicious liver nodule. Hematoxylin–eosin staining (A) showing regular liver tissue and a mesenchymal tumor, consisting of spindle-shaped cells with partly clear cytoplasm surrounding numerous, partly oddly shaped blood vessels. Immunohistochemical staining against CD34 (B) highlights endothelial cells lining small and medium sized, partly oddly shaped vessels between the tumor cells (upper half). Many tiny, rounded vessels are only discernible with this staining. The tumor cells appear more epithelioid here. CD34 also highlights small vessels within the regular liver tissue (lower half). Immunohistochemical staining against CKMNF116 (C) illustrates the mesenchymal nature of the lesion with negative tumor cells (upper half) against regular liver tissue stained positively (lower half). Immunohistochemical staining against HMB45 (D), Melan-A (E) and smooth muscle actin (F) demonstrates myomelanocytic differentiation of the tumor cells. Scale bars, 100 μm, respectively

On contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT), the lesion showed a rim enhancement in the early arterial phase and an isoenhancement in the portal venous phase (Fig. 1F). No further lesions were detected on abdominal CT. The CT of the chest showed a 6 mm-sized nodule in the right lung, which was described to be most consistent with a small granuloma. The patient underwent both upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopies with normal findings. The interdisciplinary tumor board recommended surgical resection of the PEComa due to the unknown malignant potential [4], and a follow-up of the pulmonary nodule [11].

After being informed about the recommendation for resection, the patient opted for a sonographic follow-up of her liver PEComa. The lesion was closely monitored on ultrasound initially every three months. The pulmonary nodule remained unchanged in chest CT after 6 months, so no malignancy was suspected.

No new lesions were detected and the size, sonographic features on grey-scale, and the behavior of the lesion on CEUS remained unchanged over a period of 2 years of sonographic follow-up.

Discussion

PEComas are rare mesenchymal neoplasms composed of perivascular epithelioid cells [1]. It represents a family of tumors which includes also angiomyolipoma, lymphangioleimyomatosis, rare clear-cell tumors like clear-cell “sugar” tumor of the lung and clear-cell myomelanocytic tumor of the falciform and round ligament of the liver [18]. The diagnosis of PEComa is dependent on histological confirmation, where immunohistochemical detection of HMB45 and Melan-A is decisive [2]. PEComas are usually sporadic, although in rare cases, PEComas are related to alterations in tuberous sclerosis complex [3, 12]. The histopathological differential diagnosis of liver PEComa includes hepatic adenoma, malignant melanoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), gastrointestinal neuroectodermal tumor, metastatic renal cell carcinoma, and metastatic adrenal cortical carcinoma. In addition, PEComas without adipocytic differentiation may mimic hepatocellular carcinoma (clear-cell variant) and cholangiocarcinoma requiring immunohistochemical evaluation for respective tumor markers [19].

A literature review by Liu et al. on a total of 20 cases of hepatic PEComas showed that with 18 out of 20 cases, PEComas mostly affect women and that 9 out of 20 patients were asymptomatic incidental findings [13]. The symptomatic patients complained of abdominal pain or abdominal discomfort [13]. All of this PEComas were shown to be benign lesions.

The patient presented showed no abnormalities in the laboratory tests consistent with other reports of PEComas [2, 14]. Due to the lack of a clinical presentation, the differentiation of PEComas from other incidentally found solid liver lesions is first based on imaging. Ultrasonography and especially CEUS play a predominant role in the diagnosis of incidentally found solid liver lesions, with regard to the question of whether a histologically guided biopsy is indicated [5, 15].

Consistent with previous reports, on ultrasound the PEComa appeared as a well-demarcated hypoechoic lesion, while peripheral hyperperfusion was evident on CDS [4, 6,7,8]. Early arterial hyperenhancement of the PEComa with preserved isoenhancement in the portal phase and a light parenchymal washout phenomenon were consistent with features in CEUS of previously reported hepatic PEComas [4, 6,7,8,9] (Table 1).

Due to the few cases of PEComas described so far, diagnosis by CEUS based on these characteristics is not sufficient. Furthermore, according to World Federation for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology (WFUMB) guidelines on hepatic CEUS, a hepatic adenoma, a focal nodular hyperplasia or a well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma should be considered differential diagnoses to this CEUS pattern [15].

In the literature, contrast enhancement of PEComas on CT scans shows heterogenous hyperenhancement in the arterial phase and a decrease in enhancement in the portal phase [4]. In the present case, the hepatic PEComa was characterized by a rim enhancement in the early arterial phase (Fig. 2A–C) as described in Panahova et al. and Krawczyk et al. [2, 4]. According to the patient’s desire of a conservative management a wait-and-watch strategy using regular CEUS examinations was undertaken. In one report, the MRI appearance of a benign PEComa was reported to be hypervascular with hypointense signal on T1 and hyperintense signal on T2 and no increased tracer accumulation on PET-CT [18]. In fact, PET-CT may be helpful in providing additional information regarding the malignant nature of PEComas since it was reported that malignant PEComas demonstrate higher tracer uptake and most benign PEComa have exhibited no increased tracer uptake [20].

Histologically, most hepatic PEComas appeared benign, while only few cases of malignant hepatic PEComas were reported [4, 16, 17]. However, due to the unknown risk of malignant transformation, resection should still be considered, especially as there are no established therapies for advanced stages of PEComas. The case description by Panahova et al. shows that a punch biopsy alone may not be sufficient for the assessment of malignancy, as only the surgical resectate revealed invasive growth and an increased mitotic rate [4].

A retrospective single-center study by Chen et al. suggested the use of a watch-and-wait strategy for PEComas with benign pattern, although this study only included surgically resected or locally ablated patients [14]. Overall, there is a lack of long-term experience on the treatment of hepatic PEComas, especially when considering a wait-and-watch strategy.

Conclusion

Hepatic PEComa is a rare form of hepatic neoplasms with still uncertain malignant potential. Due to the few cases described so far, a reliable diagnosis by CEUS is not possible, so that histological confirmation should also be considered. Surgical resection still seems to be indicated as the primary therapy for localized PEComas. When using a watch-and-wait strategy in benign PEComas, close monitoring should be carried out due to the unknown potential for malignant transformation.

References

Fletcher CD, Unni KK, Mertens F, editors. Pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. Lyon: IARC; 2002. p. 1–19.

Krawczyk M, Ziarkiewicz-Wróblewska B, Wróblewski T, et al. PEComa-a rare liver tumor. J Clin Med. 2021;10(8):1756.

Martignoni G, Pea M, Reghellin D, et al. PEComas: the past, the present and the future. Virchows Arch. 2008;452(2):119–32 (Epub 20071214).

Panahova S, Rempp H, Sipos B, et al. Primary perivascular epithelioid cell tumour (PEComa) of the liver - is a new entity of the liver tumors? Z Gastroenterol. 2015;53(5):399–408.

Dietrich CF. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound of benign focal liver lesions. Ultraschall Med. 2019;40(1):12–29 (Epub 20181017).

Della Vigna P, Preda L, Monfardini L, et al. Growing perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the liver studied with contrast-enhanced ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27(12):1781–5.

Akitake R, Kimura H, Sekoguchi S, et al. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) of the liver diagnosed by contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Intern Med. 2009;48(24):2083–6.

Dežman R, Mašulović D, Popovič P. Hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumor: a case report. Eur J Radiol Open. 2018;5:121–5 (Epub 20180821).

Li C, Xu JY, Liu Y. Sonazoid-enhanced ultrasonography and pathologic characters of CD68 positive cell in primary hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumors: a case report and literature review. Open Med (Wars). 2021;16(1):737–41 (Epub 20210511).

Bleeker JS, Quevedo JF, Folpe AL. “Malignant” perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm: risk stratification and treatment strategies. Sarcoma. 2012;2012: 541626 (Epub 20120426).

MacMahon H, Naidich DP, Goo JM, et al. Guidelines for management of incidental pulmonary nodules detected on CT images: from the fleischner society 2017. Radiology. 2017;284(1):228–43 (Epub 20170223).

Larque AB, Kradin RL, Chebib I, et al. Fibroma-like PEComa: a tuberous sclerosis complex-related lesion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42(4):500–5.

Liu D, Shi D, Xu Y, et al. Management of perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the liver: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2014;7(1):148–52 (Epub 20131119).

Chen W, Liu Y, Zhuang Y, et al. Hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm: a clinical and pathological experience in diagnosis and treatment. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;6(4):487–93 (Epub 20170216).

Dietrich CF, Nolsøe CP, Barr RG, et al. Guidelines and good clinical practice recommendations for contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in the liver-update 2020 WFUMB in cooperation with EFSUMB, AFSUMB, AIUM, and FLAUS. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2020;46(10):2579–604 (Epub 20200724).

Dalle I, Sciot R, de Vos R, et al. Malignant angiomyolipoma of the liver: a hitherto unreported variant. Histopathology. 2000;36(5):443–50.

Parfitt JR, Bella AJ, Izawa JI, et al. Malignant neoplasm of perivascular epithelioid cells of the liver. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(8):1219–22.

Khaja F, Carilli A, Baidas S, et al. PEComa: a perivascular epithelioid cell tumor in the liver-a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013: 904126.

.Stockman, David L. (Ed). Pecoma of Liver. In: Diagnostic Pathology: Vascular. 2016; Philadelphia: Elsevier; p. 9-26-9-31

Sun L, Sun X, Li Y, et al. The role of (18)F-FDG PET/CT imaging in patient with malignant PEComa treated with mTOR inhibitor. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:1967–70 (Epub 20150730).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Approval from the institutional review board was not required for this case report.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Matrood, S., Görg, C., Safai Zadeh, E. et al. Hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa): contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) characteristics—a case report and literature review. Clin J Gastroenterol 16, 444–449 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-023-01779-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-023-01779-w