Abstract

An 86-year-old woman presented with a history of endoscopic papillary sphincterotomy for bile duct stones and diverticulitis. The patient was admitted as an emergency case of acute cholangitis due to choledocholithiasis, underwent endoscopic bile duct stenting, and was discharged with a plan for endoscopic lithotripsy. One month later, the patient was readmitted owing to abdominal pain. Abdominal computed tomography at admission showed that the bile duct stent had migrated to the sigmoid colon and the presence of a small amount of extraintestinal gas, suggesting a colonic perforation. Lower gastrointestinal endoscopy showed adhesions and intestinal stenosis in the sigmoid colon, probably after diverticulitis, and the bile duct stent that had perforated the same site. The stent was removed and endoscopic closure of the perforation was performed using an over-the-scope clip. Abdominal computed tomography 8 days after the closure showed no extraintestinal gas. The patient resumed eating and was discharged on the 14th day of admission. There was no recurrence of abdominal pain. Endoscopic closure of sigmoid colon perforation due to bile duct stent migration using an over-the-scope clip has not been reported thus far, and it may be a new treatment option in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) plays an important role in the diagnosis and treatment of biliary and pancreatic diseases [1]. Endoscopic bile duct stenting in ERCP has been widely performed in recent years for biliary obstruction. Migration of a biliary stent is a known potential complication of ERCP, with distal migration occurring in 4%–6% cases [2, 3]. However, gastrointestinal penetration or transmural perforation due to stent migration is rare, with an incidence of < 1% [4]. Perforation due to displacement of the biliary stent can occur mainly in the duodenum and in other parts of the small intestine and the colon [5,6,7,8,9]. In recent years, endoscopic closure of gastrointestinal perforations using an over-the-scope clip (OTSC) has been shown to be effective with a high success rate [6, 10,11,12,13,14]. Here, we have reported a case of sigmoid colon perforation caused by a bile duct stent that was treated conservatively by endoscopic closure using an OTSC.

Case report

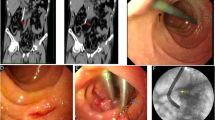

An 86-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital due to fever and abdominal pain. Blood test results showed elevated inflammatory markers and liver function test parameters. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed dilated bile ducts and stones in the common bile duct. Since the patient was diagnosed with acute cholangitis, ERCP (on the same day) and endoscopic bile duct stenting were performed (7 Fr × 7 cm straight plastic stent [QuickPlace V; Olympus, Japan]; Fig. 1). After the interventions, cholangitis improved, and the patient was discharged with a plan to undergo elective endoscopic lithotripsy in two months.

The patient had a history of endoscopic papillary sphincterotomy for bile duct stones and several episodes of diverticulitis of the sigmoid colon.

A month after discharge, the patient was readmitted to our hospital due to abdominal pain. Blood test results showed elevated inflammatory markers, but no elevation in liver function test parameters. Abdominal CT at admission showed that the bile duct stent had migrated to the sigmoid colon (Fig. 2a). The tip of the stent protruded through the wall of the sigmoid colon, and there was a small amount of extraintestinal gas around the stent, suggesting sigmoid colon perforation by the stent (Fig. 2b). Although we considered emergency surgery, we decided to treat the patient conservatively with fasting and antimicrobial administration because the patient’s vitals were stable and the patient had minimal extraintestinal gas, mild pain, and no abdominal muscular defenses. Lower gastrointestinal endoscopy performed a day after admission showed intestinal adhesions and stenosis in the sigmoid colon, probably due to diverticulitis, and the bile duct stent had perforated the same site (Fig. 3a, Fig. 4a). Endoscopic manipulation was difficult due to the stenosis of the sigmoid colon, and a marking clip was first placed near the perforation site (Fig. 3b, Fig. 4b). Next, the stent was removed by endoscopy using grasping forceps (Fig. 3c, d, Fig. 4b). An OTSC (12 × 6 mm GC; Ovesco Endoscopy AG, Germany) was then placed, the endoscope was reinserted, the perforation was confirmed (Fig. 3d), and the site of perforation was closed using the OTSC (Fig. 3e, f, Fig. 4c, d). Conservative treatment with fasting and antimicrobial agents was continued. On the eighth day of admission, abdominal CT showed no extraintestinal gas (Fig. 5a) and reduction in the inflammatory reaction; therefore, the patient was allowed to resume eating. After the resumption of meals, the patient did not have a fever or abdominal pain and was discharged on the 14th day of admission.

After discharge from the hospital, the patient did not experience abdominal pain, and 1 month after discharge, abdominal CT showed spontaneous detachment of the OTSC (Fig. 5b). Further, endoscopic lithotripsy was performed for the common bile duct stones, and the patient has been doing well since then.

Discussion

Endoscopic bile duct stenting is frequently used for the treatment of cholangitis, and stent migration is often observed as an incidental complication. The complication rate of biliary stents is 8–10%, and the most common complication is the migration of the proximal or distal part of the stent [2]. Duodenal perforation secondary to distal stent migration has been well documented in the literature. However, due to the low incidence of this life-threatening complication (< 1%) [4], prevention and treatment methods are controversial.

In our case, the patient had undergone endoscopic papillary sphincterotomy before the occurrence of bile duct stent migration. Endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) before stent placement and a long biliary stent are considered risk factors for migration of the distal part of the stent rather than the proximal part of the sent [2]. In addition to these risk factors, Arhan et al. [15] have reported that biliary stent migration is more likely to occur in cases of benign biliary stricture than in cases of malignant biliary stricture. Several reports have also shown that all migrated biliary stents are of the straight type and are more likely to migrate distally than pigtailed biliary stents [5, 16]. The double pigtail biliary stent may have an anti-migration effect as it is fixed in the bile duct, and its flexible and soft plastic may prevent intestinal perforation due to its migration. The use of pigtail stents should be considered in post-EST cases, as in this case.

Bile duct stents are rarely associated with colonic perforations. Miyasaka et al. [17] reported 22 cases of colonic perforation due to bile duct stent migration in Japan, five of which were treated with endoscopic treatment by clipping. Among cases that underwent surgery, partial resection, wedge resection, and suture closure were performed in eight cases, Hartmann’s operation was performed in five cases, and suture closure and colostomy were performed in two cases. The stent perforations were small in area and the stent lumens were narrow, which prevented feces from flowing out of the intestine; therefore, the treatment was relatively minimally invasive for colonic perforations. The sigmoid colon is often reported as a site of colorectal perforation [18, 19]. In our case, the sigmoid colon was stenotic due to repeated sigmoid diverticulitis, and the migrated bile duct stent was thought to have lodged in the sigmoid colon, resulting in a perforation.

An OTSC can close all layers of the gastrointestinal wall [20], and its efficacy has been reported in cases of gastrointestinal perforation, fistula, and refractory bleeding after endoscopic treatment [10]. Haito-Chavez et al. [21] reported suture of 14 colorectal perforations using an OTSC. Voermans et al. [22] used an OTSC in 13 cases of medically induced colorectal perforation caused by endoscopy, polypectomy, or percutaneous drainage and reported a clinical improvement rate of 92% (12/13 cases).

As shown in Table 1, 13 cases, including our case, of endoscopic closure using an OTSC for gastrointestinal perforation due to bile duct stent migration have been reported thus far [6, 12,13,14,15]. Endoscopic closure was successful in all 13 cases, and OTSC closure was considered safer than clip closure. However, two deaths were reported during the postoperative period. Therefore, the patient’s condition should be monitored after OTSC closure, and surgical intervention should be considered if necessary. To our knowledge, our case is the first case of OTSC closure for sigmoid colon perforation. In our case, there was no peritonitis or abscess formation around the sigmoid colon perforation, and after endoscopic removal of the bile duct stent, the perforation was closed using an OTSC, which allowed conservative treatment. In addition, the sigmoid colon was stenotic due to repeated diverticulitis, making endoscopic manipulation difficult and clipping at the targeted location impossible. Even when clipping was difficult, OTSC was able to close the lesion if it could get close enough. OTSC closure is effective for perforation due to bile duct stents with a small perforation area.

In conclusion, endoscopic closure with an OTSC may be a new treatment option for sigmoid colon perforation caused by bile duct stent migration.

References

Testoni PA, Mariani A, Aabakken L, et al. Papillary cannulation and sphincterotomy techniques at ERCP: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2016;48:657–83.

Arhan M, Odemiş B, Parlak E, et al. Migration of biliary plastic stents: experience of a tertiary center. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:769–75.

Bray MS, Borgert AJ, Folkers ME, et al. Outcome and management of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography perforations: a community perspective. Am J Surg. 2017;214:69–73.

Johanson JF, Schmalz MJ, Geenen JE. Incidence and risk factors for biliary and pancreatic stent migration. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:341–6.

Wang X, Qu J, Li K. Duodenal perforations secondary to a migrated biliary plastic stent successfully treated by endoscope: case-report and review of the literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:149.

Gromski MA, Bick BL, Vega D, et al. A rare complication of ERCP: duodenal perforation due to biliary stent migration. Endosc Int Open. 2020;8:E1530–6.

Issa H, Nahawi M, Bseiso B, et al. Migration of a biliary stent causing duodenal perforation and biliary peritonitis. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:523–6.

Lanteri R, Naso P, Rapisarda C, et al. Jejunal perforation for biliary stent dislocation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:908–9.

Lankisch TO, Alten TA, Lehner F, et al. (2011) Biliary stent migration with colonic perforation: a very rare complication and the lesson that should be learned from it. Gastrointest Endosc. 74(4):924–5.

Kobara H, Mori H, Nishiyama N, et al. Over-the-scope clip system: a review of 1517 cases over 9 years. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:22–30.

Bureau MA, Gkolfakis P, Blero D, et al. Lateral duodenal wall perforation due to plastic biliary stent migration: a case series of endoscopic closure. Endosc Int Open. 2020;8:E573–7.

Thapa N, Loudin M, Sharzehi K, et al. Endoscopic or conservative management of iatrogenic duodenal perforations caused by long plastic biliary stent distal migration. ACG Case Rep J. 2020;7:e00430.

Kriss M, Yen R, Fukami N, et al. Duodenal perforation secondary to migrated biliary stent in a liver transplant patient: successful endoscopic closure with an over-the-scope clip. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:1258–9.

Le Mouel JP, Hakim S, Thiebault H. Duodenal perforation caused by early migration of a biliary plastic stent: closure with over-the-scope clip. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(e6–7):S1542356518300053.

Arhan M, Ödemiş B, Parlak E, et al. Migration of biliary plastic stents: experience of a tertiary center. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:769–75.

Kawaguchi Y, Ogawa M, Kawashima Y, et al. Risk factors for proximal migration of biliary tube stents. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:1318–24.

Miyasaka M, Murakami Y, Abe H, et al. A case of perforation of the sigmoid colon caused by a biliary stent. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2017;78:1024–9.

Namdar T, Raffel AM, Topp SA, et al. Complications and treatment of migrated biliary endoprostheses: a review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5397–9.

Chittleborough TJ, Mgaieth S, Kirkby B, et al. Remove the migrated stent: sigmoid colon perforation from migrated biliary stent. ANZ J Surg. 2016;86:947–8.

Kirschniak A, Kratt T, Stüker D, et al. A new endoscopic over-the-scope clip system for treatment of lesions and bleeding in the GI tract: first clinical experiences. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:162–7.

Haito-Chavez Y, Law JK, Kratt T, et al. International multicenter experience with an over-the-scope clipping device for endoscopic management of GI defects (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:610–22.

Voermans RP, Le Moine O, von Renteln D, et al. Efficacy of endoscopic closure of acute perforations of the gastrointestinal tract. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:603–8.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing. No specific grants from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors were received for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human rights

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed consent

The patient gave informed consent to the publication of this case.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamaguchi, D., Nagatsuma, G., Jinnouchi, A. et al. Successful endoscopic closure with an over-the-scope clip for sigmoid colon perforation due to bile duct stent migration. Clin J Gastroenterol 15, 157–163 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-021-01544-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-021-01544-x