Abstract

We present the case of an 86-year-old man who had undergone left nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma (clear cell carcinoma) 22 years ago. He visited the emergency department complaining of right hypochondrial pain and fever. He was eventually diagnosed with acute cholangitis. Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed multiple tumors in the pancreas. The tumor in the pancreatic head obstructed the distal bile duct. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography detected bloody bile juice flowing from the papilla of Vater. Therefore, he was diagnosed with hemobilia. Cholangiography showed extrinsic compression of the distal bile duct; a 6 Fr endoscopic nasobiliary drainage tube was placed. Endoscopic ultrasound showed that the pancreas contained multiple well-defined hypoechoic masses. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration was performed using a 22 G needle. Pathological examination revealed clear cell carcinoma, and the final diagnosis was pancreatic metastasis of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) causing hemobilia. A partially covered metallic stent was placed in the distal bile duct. Consequently, hemobilia and cholangitis were resolved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) may recur even after a long period of time has passed from radical resection. However, it rarely results in pancreatic metastasis. Here we report a case of pancreatic metastasis of RCC that caused hemobilia 22 years after surgery; hemostasis was achieved by applying a covered-type self-expandable metallic stent (SEMS).

Case report

The case was an 86-year-old man. Nephrectomy was performed for left renal tumor 22 years ago, and the patient was pathologically diagnosed with clear cell carcinoma. Five years after the surgery, follow-up was discontinued as there was no recurrence. He had an unremarkable family history. He consumed alcohol occasionally and had never smoked.

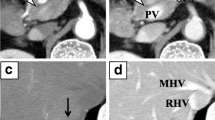

He visited the emergency department with complaints of right hypochondrial pain and fever. His vital signs at admission were as follows: body temperature, 38.5 °C; blood pressure, 94/52 mmHg; pulse rate, 114 beats/min; saturation of peripheral oxygen, 96% on room air; and respiratory rate, 18 cycles/min. Physical findings revealed conjunctival icterus and right hypochondrial tenderness. The results of a blood test showed decreased white blood cell count (2430 cells/μL); however, the C-reactive protein level was normal (0.16 mg/dL). In addition, the levels of total bilirubin (2.0 mg/dL), direct bilirubin (1.2 mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase (736 U/L), alanine transaminase (350 U/L), alanine transaminase (478 U/L), and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (281 U/L) increased. Meanwhile, the results for the tumor markers were within normal ranges (cancer antigen 19–9, < 37 U/mL; carcinoembryonic antigen, 1.3 ng/dL; and Dupan-2, 36 U/mL) (Table 1). Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed multiple tumors in the pancreas. In particular, a tumor in the pancreatic head compressed the bile duct, and the intrahepatic/extrahepatic bile duct was dilated (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging showed multiple tumors in the pancreas with heterogeneously low signal intensity on the T1-weighted image. Bile in the common bile duct and gallbladder neck has high intensity, which suggests hemobilia (Fig. 2a). Pancreatic masses have rather low intensity on T2WI, suggesting intratumor bleeding. Area with high intensity in pancreas head mass is considered as tumor necrosis (Fig. 2b). Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (b-factor = 1000 s/mm2) showed multiple tumors in the pancreas with a high signal intensity (Fig. 3). Apparent diffusion coefficient map revealed pancreatic tumors with low intensity.

a Magnetic resonance imaging showed multiple tumors in the pancreas with heterogeneously low signal intensity on the T1-weighted image. Bile in the common bile duct and gallbladder neck has high intensity, which suggests hemobilia. b Pancreatic masses have rather low intensity on T2WI, suggesting intratumor bleeding. Area with high intensity in pancreas head mass is considered as tumor necrosis

The patient was diagnosed with acute cholangitis (Tokyo Guidelines 2018, Grade II of severity criteria [1]). Subsequently, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed, revealing the flow of bloody bile juice from the papilla of Vater; therefore, the patient was diagnosed with hemobilia. A 6 Fr endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) tube was placed. Cholangiography via the endoscopic naso-biliary drainage revealed that the distal bile duct was extrinsically compressed by the tumor (Fig. 4). Acute cholangitis improved after ENBD placement, but hemibilia persisted. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) detected multiple well-defined hypoechoic masses in the pancreas, and Doppler ultrasound showed abundant blood flow inside the mass (Fig. 5a, b). A tumor in the pancreatic tail underwent EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) using a 22 G needle (Expect™ SlimLine, Boston Scientific Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Pathological examination revealed round-shaped tumor cells with clear cytoplasm, indicating clear cell carcinoma (Fig. 5c). Surgical and pathological reports of surgical resection of RCC 22 years ago were not available, but based on the clinical images and pathological findings of EUS-FNA, the patient was diagnosed with multiple pancreatic metastases from RCC. Another ERCP was performed, and a partially covered SEMS with 10 mm diameter and 80 mm length (WallFlex™ Biliary RX Stent, Boston Scientific Japan, Tokyo, Japan) was placed after small-incision endoscopic sphincterotomy (Fig. 6). Postoperatively, hemobilia and acute cholangitis were resolved. One month after the SEMS placement, the hemoglobin level increased to 12.5 g/dL.

Considering that the patient and his family refused chemotherapy, palliative treatment was continued. Two years have passed, since the stent was placed, no SEMS migration has occurred, and no hemobilia nor acute cholangitis has been observed, Fig. 7.

Discussion

RCC mostly metastasizes in the lung (45.2%), bone (29.5%), lymph nodes (21.8%), liver (20.3%), adrenal gland (8.9%), and brain (8.1%) and rarely in the pancreas [2]. In previous reports, the rate of pancreatic metastasis was approximately 3% [3]; 2–5% of all pancreatic malignancies were metastatic tumors [4]. Meanwhile, among the surgically resected metastatic pancreatic tumors, those with primary RCC are the most common, accounting for 58.6–70% [5,6,7].

In cases of pancreatic metastasis of RCC, the mean period from nephrectomy to pancreatic metastasis is 6.9–14.6 years [8,9,10,11,12,13]. In some cases, pancreatic metastasis was even confirmed after 32.7 years of remission [12]. Therefore, despite reaching 22 years postoperatively, as in the present case, pancreatic metastasis should be considered in patients with a history of RCC.

Hemobilia is a rare condition that was first reported by Sandblom in 1948 [14]. Iatrogenicity is the most well-known cause of biliary bleeding (65%), whereas neoplasm is relatively rare (7%) [15]. Of the malignant neoplasms causing hemobilia, hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, gallbladder cancer, and pancreatic cancer are the most common, accounting for 50%, 35.7%, 7.1%, and 7.1%, respectively, whereas RCC causing hemobilia is rare [16].

A literature search for “hemobilia, renal cell carcinoma” in PubMed revealed only one case of hemobilia caused by RCC [17]. Herein, hemobilia occurred because of bleeding from a metastatic gallbladder tumor from RCC. RCC is a hypervascular tumor that can cause tumor bleeding. It often grows by expansion rather than infiltration. In the present case, a metastatic tumor in the pancreatic head compressed the distal bile duct severely, causing a minor perforation of the bile duct wall and exposing the tumor into the bile duct. Although direct cholangioscopy could be useful for definitive diagnosis, securing a visual field may be difficult when hemobilia persists; thus, the policy was to prioritize hemostasis and biliary drainage. Hemostasis cannot be achieved using a plastic stent; hence, we used a partially covered SEMS, which successfully stopped the bleeding.

There are two types of covered SEMS: fully covered SEMS and partially covered SEMS. The present case showed a “compressive” biliary stenosis, which may be more loosened than the “invasive” stenosis, such as that in pancreatic cancer. Therefore, a partially covered SEMS, with uncovered parts at both ends, was used to anchor the stent. Two years have passed since the procedure, but no stent migration has been observed.

We searched PubMed for cases in which hemobilia was managed with a metallic stent from 2000 to 2020 with the keyword "haemobilia, metallic stent". As a result, nine cases were collected, including our case (Table 2). The average age is 67 years, male 7 cases, female 2 cases, primary disease is cholangiocarcinoma 2 cases, portal biliopathy 2 cases, liver metastasis of rectal cancer1 case, hepatocellular carcinoma 1 case, pancreatic cancer 1 case, gallbladder cancer 1 case, and pancreatic metastasis of renal cell carcinoma 1 case. The stent type was fully covered in 7 cases, partially covered in 2 cases, and the stent location was distal bile duct in 5 cases, hilar in 3 cases, and hilar to distal in 1 case. Hemostasis was successful in all cases, and no complications were found. Metallic stents for hemobilia seems to be an effective treatment. In the covered type, the stent presses on the surrounding tissue, which can perform compression hemostasis.

Conclusion

This report presents a case of hemobilia caused by pancreatic metastasis of RCC. Pancreatic metastases should be considered in patients with a RCC history, even long after surgery. EUS-FNA effectively confirmed the histological diagnosis, and covered-SEMS compression was effective for hemobilia caused by pancreatic head metastatic tumor.

References

Kiriyama S, Kozaka K, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholangitis (with videos). J Hepatobil Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:17–30.

Bianchi M, Sun M, Jeldres C, et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in renal cell carcinoma: a population-based analysis. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:973–80.

Rypens F, Van Gansbeke D, Lambilliotte JP, et al. Pancreatic metastasis from renal cell carcinoma. Br J Radiol. 1992;65:547–8.

Ballarin R, Spaggiari M, Cautero N, et al. Pancreatic metastases from renal cell carcinoma: the state of the art. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4747–56.

Adler H, Redmond CE, Heneghan HM, et al. Pancreatectomy for metastatic disease: a systematic review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:379–86.

Sperti C, Moletta L, Patanè G. Metastatic tumors to the pancreas: the role of surgery. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2014;6:381–92.

Madkhali AA, Shin SH, Song KB, et al. Pancreatectomy for a secondary metastasis to the pancreas: A single-institution experience. Medicine. 2018;97: e12653.

Zerbi A, Ortolano E, Balzano G, et al. Pancreatic metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: which patients benefit from surgical resection? Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1161–8.

Showalter SL, Hager E, Yeo CJ. Metastatic disease to the pancreas and spleen. Semin Oncol. 2008;35:160–71.

Law CH, Wei AC, Hanna SS, et al. Pancreatic resection for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: presentation, treatment, and outcome. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:922–6.

Sellner F, Tykalsky N, De Santis M, et al. Solitary and multiple isolated metastases of clear cell renal carcinoma to the pancreas: an indication for pancreatic surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:75–85.

Thompson LD, Heffess CS. Renal cell carcinoma to the pancreas in surgical pathology material. Cancer. 2000;89:1076–88.

Mechó S, Quiroga S, Cuèllar H, Sebastià C. Pancreatic metastasis of renal cell carcinoma: multidetector CT findings. Abdom Imaging. 2009;34:385–9.

Sandblom P. Hemorrhage into the biliary tract following trauma; traumatic hemobilia. Surgery. 1948;24:571–86.

Green MH, Duell RM, Johnson CD, Jamieson NV. Haemobilia. Br J Surg. 2001;88:773–86.

Kim KH, Kim TN. Etiology, clinical features, and endoscopic management of hemobilia: a retrospective analysis of 37 cases. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2012;59:296–302.

Fullarton GM, Burgoyne M. Gallbladder and pancreatic metastases from bilateral renal carcinoma presenting with hematobilia and anemia. Urology. 1991;38:184–6.

Rerknimitr R, Kongkam P, Kullavanijaya P. Treatment of tumor associated hemobilia with a partially covered metallic stent. Endoscopy. 2007;39:E225.

Layec S, D’Halluin PN, Pagenault M, et al. Massive hemobilia during extraction of a covered self-expandable metal stent in a patient with portal hypertensive biliopathy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:555–6.

Bagla P, Erim T, Berzin TM, et al. Massive hemobilia during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in a patient with cholangiocarcinoma: a case report. Endoscopy. 2012;44:E1.

Kawaguchi Y, Ogawa M, Maruno A, et al. A case of successful placement of a fully covered metallic stent for hemobilia secondary to hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct invasion. Case Rep Oncol. 2012;5:682–6.

Goenka MK, Harwani Y, Rai V, et al. Fully covered self-expandable metal biliary stent for hemobilia caused by portal biliopathy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:1175.

Barresi L, Tarantino I, Ligresti D, et al. Fully covered self-expandable metal stent treatment of spurting bleeding into the biliary tract after endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of a solid lesion of the pancreatic head. Endoscopy. 2015;47:E87–8.

Zhang L, Craig PI. A case of hemobilia secondary to cancer of the gallbladder confirmed by cholangioscopy and treated with a fully covered self-expanding metal stent. VideoGIE. 2018;3:381–3.

Tien T, Tan YC, Baptiste P, et al. Haemobilia in a previously stented hilar cholangiocarcinoma: successful haemostasis after the insertion of fcSEMS. Oxf Med Case Reports. 2020; 2020: omaa010

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamawaki, M., Takano, Y., Noda, J. et al. A case of hemobilia caused by pancreatic metastasis of renal cell carcinoma treated with a covered metallic stent. Clin J Gastroenterol 15, 210–215 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-021-01532-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-021-01532-1