Abstract

Introduction

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is a common, chronic inflammatory skin condition associated with significant impact on quality of life, yet its etiology and pathophysiology are not well understood. With significant impact on patients’ quality of life, understanding the diagnostic pathway from the perspectives of patient and healthcare providers (HCPs) is crucial.

Methods

An online survey was developed and administered in conjunction with the Harris Poll to gain insight into patient and HCP perspectives about SD diagnosis and management from December 2021 to January 2022.

Results

Most patients were unaware of SD before their diagnosis (71%) and experienced difficulty finding information online (56%). Patients delayed seeking medical attention for SD by an average of 3.6 years, with most patients feeling their symptoms did not require medical attention (63%), a perception that HCPs correctly anticipated. Additionally, most patients (58%) reported embarrassment discussing their SD symptoms with HCPs, a factor HCPs underestimated. HCPs also underestimated the percentage of patients self-reporting moderate-severity SD. Patients preferred dermatology HCPs for SD treatment (79%), and reported visiting an average of 2.3 different HCPs, with 75% of patients seeing more than one provider.

Conclusion

These insights highlight the complexities in the diagnostic and management pathways of SD and underscore the need for a more nuanced understanding and approach in addressing the condition.

Infographic available for this article.

Infographic

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Patients delayed seeing a provider for seborrheic dermatitis by an average of 3.6 years, with most patients feeling their symptoms did not require medical attention (63%). |

Most patients (58%) reported embarrassment discussing their SD symptoms with HCPs, a factor HCPs underestimated. |

Patients preferred dermatology health care for seborrheic dermatitis treatment (79%), with 75% of patients seeing more than one provider. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including an infographic to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article, go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26871205.

Introduction

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is a common, chronic inflammatory skin disease with an estimated worldwide prevalence of nearly 5% [1, 2]. The highest risk appears to be among patients aged ≥ 75 years and those of White race, although the authors cautioned that the latter may reflect an under-recognition of SD in individuals with darker skin tones rather than an actual lower risk [2]. SD has a significant negative impact on quality of life (QoL) and is associated with anxiety and loss of self-esteem [3,4,5,6]. Risk factors for presentation or exacerbation of SD include environment (particularly hot weather [4]), HIV-positive status, Parkinson disease, diet, and male sex [7]. Despite its prevalence, the etiology of SD is not well established, the pathophysiology of the disease is not fully understood [8, 9], and its epidemiology and patient burden remain underexplored.

Effective SD management is complex and characterized by heterogenous clinical presentations, approach to diagnosis, and treatment patterns, underscoring the need for more complete understanding of the journey from sign/symptom onset, diagnosis, and subsequent treatment [10]. Although existing studies have primarily focused on clinical aspects and treatment efficacy of SD, there is a notable lack of insight into the patient perspective and the real-world experiences of healthcare providers (HCPs) [7]. Patients often struggle to attain sustained remission, and the occurrence of flares is common, highlighting the necessity for a treatment approach that is as individualized as the disease manifestations themselves [10]. Delays in care, whether from the patient’s or HCP’s side, can lead to prolonged discomfort and distress. Here, we aim to explore the SD diagnosis pathway from both patient and HCP perspectives.

Methods

The authors developed online surveys to gain deeper insights into the behaviors, experiences, preferences, and attitudes of patients and HCPs as they relate to SD diagnosis and management. The patient and HCP surveys were administered by The Harris Poll, an independent market research and analytics company focusing on public opinion research. Each survey was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its later amendments and Good Clinical Practice guidelines of the International Council for Harmonisation. The survey was not reviewed by an ethics committee and, due to the nature of the survey and information collected, is exempt from this requirement based on the Human Subject Regulations Decision Charts: 2018 Requirements: 45 CFR 46.104(d)(2) for Educational Tests, Surveys, Interviews, or Observation of Public Behavior.

The patient survey was a 10-min online survey conducted from December 14, 2021 through January 19, 2022 and included adults aged ≥ 18 years who reported having been diagnosed with SD by an HCP. Participants provided consent to participate in the survey and for the data to be reported in aggregate, not individually. No identifying information was included for any patient participant. Participants were aware that the results would be published in a journal. Data for age, sex, education, race/ethnicity, region, income, household size, and marital status were weighted, when necessary, to align results with actual proportions in the population. Data from patients who self-identified as Black or African American were adjusted to natural fallout among the qualified patients. A propensity score variable was also included to adjust for respondents’ propensity to be online. Overall, 23,887 individuals clicked on the survey and 300 were qualified and completed the survey to its entirety.

The HCP survey was a 12-min online survey conducted from December 16, 2021 through January 19, 2022 and included HCPs specializing in dermatology [including dermatologists, nurse practitioners (NPs), and physician assistants (PAs)] who saw ≥ 1 patient per week and regularly saw ≥ 1 patients with SD per year. HCPs provided consent to participate in the survey, for the data to be reported in aggregate (not individually), and were aware that the results would be published in a journal. No identifying information was included for any HCP participant. For dermatologists, data for years in practice, sex, and region were weighted, when necessary, to align results with actual proportions in the population. For NPs and PAs, raw data were not weighted and, therefore, are representative only of the individuals who completed the survey. Overall, 1320 HCPs clicked through the survey, and 601 were qualified and completed the survey. Significance testing of results for key subgroups were conducted using a t test at a 95% confidence level.

Results

Patient and HCP Demographics

The mean age of patients who completed the survey was 40 years, and 55% were male (Table 1; n = 300). About two-thirds (67%) of the HCPs were physicians, 24% were PAs, and 10% were NPs. The mean number of years in practice was 3.1 and the mean number of patients seen per week, for all skin conditions, was 157.7 (Table 2).

Availability of Information and Initial Perceptions of SD Before Diagnosis

Over half (56%) of patients said it was difficult to find information about SD and 71% said they had not heard of SD before diagnosis (Fig. 1). Most (86%) HCPs felt that ‘most patients had not heard of SD before their diagnosis.’ Most patients (83%) did not realize all their symptoms were due to SD and 76% mistook their symptoms for another skin condition (Fig. 1). Similarly, most HCPs agreed that patients did not realize all their symptoms were due to SD (96%) and thought they mistook their symptoms for another skin condition (91%). Almost all patients (90%) wished they had known there were specific symptoms to identify SD; 85% of HCPs agreed their patients felt similarly (Fig. 1).

Patients reported that, before diagnosis, they felt embarrassed to seek medical attention (58%) or that they did not need medical attention for their SD symptoms (63%) (Fig. 2). Among the patients who reported a strong impact of SD on their life (n = 124), 72% felt embarrassed discussing their symptoms with their HCP. This rate of embarrassment was significantly higher (P < 0.05) compared with patients who reported some impact (50%, n = 74/147) or no impact (43%, n = 12/28) of SD on their lives. Over half (63%) of patients thought their symptoms were not severe enough to warrant medical attention. Likewise, 66% of HCPs agreed that patients did not feel their symptoms were severe enough. Most patients were embarrassed to talk to family or friends (59%) and HCPs (58%) about symptoms. Although 65% of HCPs agreed that patients were embarrassed to talk to their family and friends, HCPs were less likely to recognize that patients felt embarrassed to talk to them about their symptoms (32% of HCPs).

HCPs underestimated the time it takes for patients experiencing SD symptoms to seek care. The average estimated time that HCPs reported patients experience symptoms before seeking a dermatology HCP for treatment or diagnosis was 1.6 years (Fig. 3). Over one-third (38%) of HCPs estimated that it takes < 1 year before patients see an HCP. In contrast, the average estimated time patients reported experiencing SD symptoms before visiting an HCP specifically for those symptoms was 3.6 years (Fig. 3), with 20% stating that it took ≥ 6 years. A higher percentage of patients reporting severe disease sought treatment from an HCP within 1 year of symptom onset (Fig. 3).

Actions Taken by Patients before Seeking Help from an HCP

Before seeking help from an HCP, > 50% of patients tried over-the-counter (OTC) treatments (65%), researched their own symptoms (57%), or tried alternative treatments (51%) (Fig. 4). Almost half (48%) looked for advice on websites or online communities for others with similar symptoms. Although HCPs agreed that patients were already using other therapies before they first started treating them, they estimated a smaller proportion using OTC (shampoos: 37%; moisturizers: 24%; topical steroids: 10%) or alternative treatments (12%). Among patients who tried OTC or alternative treatments before seeking help from an HCP, respondents tried an average of 5.9 OTC treatments and 4.2 alternative treatments first.

Patient and HCP Views on the Pathway to Diagnosis

For self-reported symptom severity, 16% of patients reported mild symptoms, 71% reported moderate symptoms, and 13% reported severe symptoms. In contrast, HCPs reported that 40% of patients had mild symptoms, 41% had moderate symptoms, and 19% had severe symptoms (Table 3). Itching (61%) and flaking (60%) on the scalp and redness (50%) on the scalp, face, and neck were reported as the most bothersome symptoms by patients, although similar symptoms on other areas of the body also had negative impact on patients. Of the total patients, 50% reported these scalp symptoms to be very or moderately bothersome.

Many patients said that a variety of non-HCP individuals helped them identify their SD symptoms. Before visiting an HCP, patients said family members (45%), hair stylists/barbers (25%), and friends (22%) helped them identify SD as the cause of their symptoms (Fig. 5). Among these patients (n = 223), 48% said conversations with non-HCPs made them feel better about their SD symptoms, 29% said they felt no better or worse, and 23% said they felt worse about their symptoms.

The majority of dermatology HCPs (77%) reported that patients come to them directly with symptoms of SD, with 50% having SD as their primary complaint (Fig. 6). Only 23% of HCPs reported that patients obtained referrals from another HCP before visiting a dermatology specialist. Very few dermatology HCPs (6%) reported having patients referred by another HCP with a diagnosis of SD.

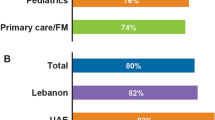

Management of SD by an HCP

When asked which type of HCPs they prefer to see for SD management (they could select more than one), patients said they prefer a dermatology HCP (79%), followed by primary care provider (28%) and general practitioner (20%). Patients reported visiting an average of 2.3 different HCPs for SD treatment over the course of their disease, and 75% have seen more than one HCP. Patients said they visit the primary HCP who manages their SD an average of 4.6 times per year, and 85% said they still actively work with their HCP for SD treatment. Among the 43 patients (15%) who reported that they stopped seeing their HCP, reasons for discontinuation included improvement in symptoms (50%), ability to manage SD without prescription treatments (24%), and difficulty navigating insurance coverage for treatments (20%; Fig. 7).

Discussion

This study represents the first comprehensive exploration of the diagnostic and management pathways of SD from both the patient and HCP perspectives. We discovered a significant delay in patients seeking medical attention for their SD, with an average wait time of 3.6 years. This delay contrasts sharply with the more prompt response seen in other common inflammatory dermatologic conditions like psoriasis, where patients typically seek care within 3 months [11,12,13]. A majority of patients reported feeling embarrassed to discuss their SD symptoms with HCPs, which has been associated with delays in seeking medical care for a variety of conditions [14]. However, our results suggest that HCPs may significantly underestimate how much this factor impacts patients with SD.

Additionally, these findings indicate a prevalent attitude among patients that their symptoms do not warrant medical attention and in some cases may be considered a cosmetic condition, accompanied by a tendency towards self-management. Before consulting HCPs, patients commonly attempted to treat their symptoms independently, with an average of six over-the-counter treatments used. This tendency to self-manage and downplay the condition aligns with behaviors observed in hair loss disorders, where patients may frequently feel their symptoms do not warrant medical intervention, or in acne or fungal infections, where self-treatment is a common initial response [15]. These patterns mirror a wider tendency in dermatology for patients to downplay or delay addressing their own symptoms if perceived as medically non-urgent, despite their potential significant emotional and psychological impact [16,17,18].

Despite often being seen as a mild condition, SD is associated with considerable implications for QoL, particularly in female and younger patients [3,4,5, 19]. Feelings of shame, embarrassment, and self-consciousness are common among patients with SD, as are practical considerations like impacts to clothing choices [19], with significant emotional impact reported by nearly half of patients with SD in a large study from China [20].

However, the results of the present study highlight a disparity in HCPs’ understanding of patient experiences with SD. HCPs tended to overestimate the number of patients who were unaware of their SD symptoms or who mistakenly attributed symptoms to a different condition, while also frequently underestimating the duration of symptoms before patients sought care. This gap suggests a need for improved HCP awareness about the lived experiences of individuals with SD and points to the importance of enhancing patient-HCP communication.

Furthermore, we observed a striking disconnect between patient-reported symptom severity and the assessments of HCPs. Although 71% of patients reported their symptoms as moderate severity, HCPs estimated this figure to be substantially lower at 41%. This discrepancy suggests that the visible signs of SD might not accurately reflect symptom severity, a finding consistent with observations in atopic dermatitis, where patients with mild lesions can still experience increased disease severity due to non-visible disease burdens [21]. SD symptoms that are often clinically classified as mild may, in fact, impose a significant burden, highlighting the need for HCPs to recalibrate their perceptions to align more accurately with patient experiences.

This study sheds light on the challenges patients face in seeking information and guidance for SD. Although many patients reported a lack of familiarity with SD, there was a clear indication of their active pursuit of information, with the majority of patients researching their symptoms on the internet. However, scarcity of accurate and accessible information could drive patients to resort to less credible online resources for self-diagnosis and symptom management. Evidence suggests that patients are more likely to consult videos about SD on social media platforms where content is predominantly non-HCP-made, often featuring inaccurate and non-educational information [22]. This pattern is consistent with broader trends in dermatology, where patients frequently use online resources to address their skin conditions, impacting their willingness to seek professional medical care [23]. Self-treatment, despite its prevalence, has been linked to worse outcomes in dermatology [24], underscoring the need for improved access to trustworthy and accurate medical information.

Interestingly, the findings revealed that non-HCPs often play a crucial role in the initial identification of SD, emphasizing the importance of community awareness and knowledge about SD. Family members, nutritionists, hairstylists, barbers, estheticians, and others with SD or similar conditions were instrumental in recognizing symptoms in many patients, highlighting the value of support groups and community networks as vital resources. These findings suggest a need for public health education to facilitate earlier detection and treatment while also addressing and potentially reducing stigma, a strategy that has proven effective in several other medical conditions [25,26,27].

Despite a common perception that SD is straightforward to diagnose, these data suggest a more complex reality. Notably, 74% of the patients referred by non-dermatology HCPs received an initial misdiagnosis, highlighting a gap in SD recognition among general healthcare practitioners. The symptoms of SD can sometimes be confused with other skin conditions like psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, or rosacea [28], and its diagnosis can be particularly challenging in darker skin tones [29]. Additionally, our findings show that although most patients prefer seeing dermatology HCPs for SD management, they often consult > 2 HCPs, indicating a journey through multiple healthcare touchpoints before receiving effective treatment. These insights emphasize the need for enhanced training and awareness among all HCPs, advocating for a multidisciplinary approach in early SD detection and referral, especially in diverse populations where symptom presentation can vary significantly.

Limitations of the current study include potential challenges in fully capturing the diverse experiences and behaviors of individuals affected by SD using a cross-sectional online survey method. The weighting of demographic data might not completely account for the varied nuances in patient experiences across different demographic groups, and the self-reported nature of the survey could introduce bias in the responses. Insights from this study indicate a need for further prospective research focused on patient and HCP perspectives to inform better healthcare practices.

Conclusion

As the first comprehensive description of the journey to SD diagnosis, this study reveals key insights into its impact and treatment. These observations emphasize the urgent need for enhanced education to highlight the QoL implications of SD and facilitate timely and appropriate care, challenging the common perception of SD as a condition of low priority. The results notably highlight a critical need for improved HCP awareness and training about the realities of living with, managing, and referring for SD. Addressing these issues is key to improving the overall management and outcomes for patients with SD.

Data Availability

Data collected for this study will be made available to others. Proposals for data requests will be reviewed and considered for sharing following review of the proposal.

References

Polaskey MT, Chang CH, Daftary K, Fakhraie S, Miller CH, Chovatiya R. The global prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160(8):846–855. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.1987.

Haq Z, Abdi P, Wan V, Diaz MJ, Aflatooni S, Mirza FN, et al. Epidemiology of seborrheic dermatitis among adults in the United States: a cross-sectional analysis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316(7):394.

Peyrí J, Lleonart M. Clinical and therapeutic profile and quality of life of patients with seborrheic dermatitis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007;98(7):476–82.

Araya M, Kulthanan K, Jiamton S. Clinical Characteristics and quality of life of seborrheic dermatitis patients in a tropical country. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60(5):519.

Szepietowski JC, Reich A, Wesołowska-Szepietowska E, Baran E. Quality of life in patients suffering from seborrheic dermatitis: influence of age, gender and education level. Mycoses. 2009;52(4):357–63.

Pärna E, Aluoja A, Kingo K. Quality of life and emotional state in chronic skin disease. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(3):312–6.

Jackson JM, Alexis A, Zirwas M, Taylor S. Unmet needs for patients with seborrheic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90(3):597–604.

Dessinioti C, Katsambas A. Seborrheic dermatitis: etiology, risk factors, and treatments: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31(4):343–51.

Wikramanayake TC, Borda LJ, Miteva M, Paus R. Seborrheic dermatitis-looking beyond Malassezia. Exp Dermatol. 2019;28(9):991–1001.

Dall’Oglio F, Nasca MR, Gerbino C, Micali G. An overview of the diagnosis and management of seborrheic dermatitis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2022;15:1537–48.

Quiroz-Vergara JC, Morales-Sánchez MA, Castillo-Rojas G, López-Vidal Y, Peralta-Pedrero ML, Jurado-Santa Cruz F, et al. Diagnóstico tardío de psoriasis: motivos y consecuencias. Gac Med Mex. 2017;153(3):335–43.

Swetter SM, Soon S, Harrington CR, Chen SC. Effect of health care delivery models on melanoma thickness and stage in a university-based referral center: an observational pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(1):30–6.

Baade PD, English DR, Youl PH, McPherson M, Elwood JM, Aitken JF. The relationship between melanoma thickness and time to diagnosis in a large population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(11):1422–7.

Scott S, Walter F. Studying help-seeking for symptoms: the challenges of methods and models. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2010;4(8):531–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00287.x.

Richard MA, Paul C, Nijsten T, Gisondi P, Salavastru C, Taieb C, et al. The journey of patients with skin diseases from the first consultation to the diagnosis in a representative sample of the European general population from the EADV burden of skin diseases study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(Suppl 7):17–24.

Bahalah SO. Beliefs, attitudes, and treatment-seeking behavior among patients with acne vulgaris: a cross-sectional study from Yemen. Gulf J Dermatol Venereol. 2017;24(2):9–14. https://www.gulfdermajournal.net/pdf/2017-10/2.pdf.

Wisuthsarewong W, Nitiyarom R, Kanchanapenkul D, Arunkajohnask S, Limphoka P, Boonchai W. Acne beliefs, treatment-seeking behaviors, information media usage, and impact on daily living activities of Thai acne patients. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19(5):1191–5.

Suh DH, Shin JW, Min SU, Lee DH, Yoon MY, Kim NI, et al. Treatment-seeking behaviors and related epidemiological features in Korean acne patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2008;23(6):969–74.

Sampogna F, Linder D, Piaserico S, Altomare G, Bortune M, Calzavara-Pinton P, et al. Quality of life assessment of patients with scalp dermatitis using the Italian version of the Scalpdex. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94(4):411–4.

Xuan M, Lu C, He Z. Clinical characteristics and quality of life in seborrheic dermatitis patients: a cross-sectional study in China. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):308.

Chovatiya R, Lei D, Ahmed A, Chavda R, Gabriel S, Silverberg JI. Clinical phenotyping of atopic dermatitis using combined itch and lesional severity: a prospective observational study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;127(1):83-90.e2.

Fakhraie S, Erickson T, Chovatiya R. Evaluation of a patient education platform for seborrheic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315(10):2927–30.

Wolf JA, Moreau JF, Patton TJ, Winger DG, Ferris LK. Prevalence and impact of health-related internet and smartphone use among dermatology patients. Cutis. 2015;95(6):323–8.

Saxena A, Dey VK, Srivastava P, et al. Treatment-seeking behavior of patients attending department of dermatology in a tertiary care hospital and their impact on disease. Med J Dr DY Patil Vidyapeeth. 2023;16(2):167–72. https://doi.org/10.4103/mjdrdypu.mjdrdypu_123_21.

Wallhed Finn S, Mejldal A, Baskaran R, Nielsen AS. Effects of media campaign videos on stigma and attitudes towards treatment seeking for alcohol use disorder: a randomized controlled study. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1919.

Jagota P, Jongsuntisuk P, Plengsri R, Chokpatcharavate M, Phokaewvarangkul O, Chirapravati V, et al. If your patients were too embarrassed to go out in public, what would you do? - Public education to break the stigma on Parkinson’s disease using integrated media. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2020;11:143–8.

Betton V, Borschmann R, Docherty M, Coleman S, Brown M, Henderson C. The role of social media in reducing stigma and discrimination. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;206(6):443–4.

Berk T, Scheinfeld N. Seborrheic dermatitis. P T. 2010;35(6):348–52.

Clark GW, Pope SM, Jaboori KA. Diagnosis and treatment of seborrheic dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(3):185–90.

Acknowledgements

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Thank you to the respondents for their participation in the surveys. This study was supported by Arcutis Biotherapeutics, Inc. Writing support was provided by Lauren Ramsey, PharmD, and Devanshi Rai, PharmD, of Alligent Biopharm Consulting LLC, and funded by Arcutis Biotherapeutics, Inc.

Funding

This work and the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access Fees were funded by Arcutis Biotherapeutics, Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Raj Chovatiya, Meredith T. Polaskey, Lakshi Aldredge, Candrice Heath, Moises Acevedo, David H. Chu, Diane Hanna, Melissa S. Seal, and Matthew Zirwas had full access to all the data in the study and they all take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors contributed to the concept and design; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Raj Chovatiya, Lakshi Aldredge, Candrice Heath, Moises Acevedo, and Matthew Zirwas are investigators and/or consultants for Arcutis Biotherapeutics, Inc. and received grants/research funding and/or honoraria. David H. Chu, Diane Hanna, and Melissa S. Seal are employees of Arcutis Biotherapeutics, Inc. Meredith Tyree Polaskey has no disclosures to report.

Ethical Approval

The survey was not reviewed by an ethics committee and due to the nature of the survey and information collected is exempt from this requirement based on the Human Subject Regulations Decision Charts: 2018 Requirements: 45 CFR 46.104(d)(2) for Educational Tests, Surveys, Interviews, or Observation of Public Behavior. The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its later amendments and Good Clinical Practice guidelines of the International Council for Harmonisation. Before enrollment of patients, the study protocol and informed consent form were reviewed and approved by an appropriate Institutional Review Board or Independent Ethics Committee. Participants provided consent to participate in the survey and for the data to be reported in aggregate.

Additional information

Prior Presentation: American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) Annual Meeting; Mar 17–21, 2023; New Orleans, LA.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chovatiya, R., Polaskey, M.T., Aldredge, L. et al. Patient and Healthcare Provider Perspectives on the Pathway to Diagnosis of Seborrheic Dermatitis in the United States. Adv Ther (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-024-02986-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-024-02986-8