Abstract

Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is an indolent subtype of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL), characterized by a long natural course of remissions/relapses. We aimed to evaluate real-world quality of life (QoL) in patients with FL, by line of therapy (LOT), and across countries.

Methods

Data were drawn from the Adelphi FL Disease Specific Programme™, a cross-sectional survey of physicians and their patients in Europe [France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom (UK)], and the United States (US) from June 2021 to January 2022. Patients provided demographics and patient-reported outcomes via the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QoL questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30). Bivariate analysis assessed QoL versus NHL, across LOT [first line (1L), second line (2L), third line or later (3L+)] and country.

Results

Patients (n = 401) had a mean [standard deviation (SD)] age of 66.0 (9.24) years, 58.1% were male, and 41.9%/22.9% were Ann Arbor stage III/IV. Patients with FL mean EORTC global health status (GHS)/QoL, nausea/vomiting, pain, dyspnea, appetite loss, and diarrhea scores were statistically significantly worse (p < 0.05) versus the NHL reference values. Mean (SD) GHS/QoL worsened from 1L [56.5 (22.21)] to 3L+ [50.4 (20.11)]. Physical and role functioning, fatigue, pain, dyspnea, and diarrhea scores also significantly worsened across later LOTs (p < 0.05). Across all functional domains, mean scores were significantly lower (p < 0.05) and almost all symptom scores (excluding diarrhea) were significantly higher (p < 0.05) for European versus US patients.

Conclusions

Patients with FL at later LOTs had significantly worse scores in most QoL aspects than earlier LOTs. European patients had significantly lower functioning and higher symptom burden than in the US. These real-world findings highlight the need for novel FL therapies that alleviate patient burden, positively impacting QoL.

Plain Language Summary

There is little information about the effects of follicular lymphoma and treatments on quality of life as assessed by patients. We surveyed doctors and their patients with follicular lymphoma across France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States (US), and asked patients to complete a form reporting their quality of life. A total of 401 patients were included.

In general, patients with follicular lymphoma treated across all lines of treatment had worse quality of life and symptoms of nausea and vomiting, pain, shortness of breath, appetite loss, and diarrhea compared to a reference group of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). Overall quality of life and physical, role, and social functioning of patients with follicular lymphoma worsened from the first to the third line of treatment. Fatigue, pain, dyspnea, and diarrhea symptom scores also worsened across the lines of therapies. European patients had worse quality of life, functioning, and symptoms compared to US patients. Better treatments are needed to improve symptoms, functions, and quality of life for patients with follicular lymphoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

The quality of life (QoL) of patients with relapsing–remitting chronic diseases plays an important role in clinical decision-making by physicians and their patients regarding treatment. |

Few studies evaluate real-world, patient-reported health outcomes and QoL in follicular lymphoma (FL). These outcomes are important, as prolonged survival in these patients incurs a longer-term disease and treatment burden, as well as possible deterioration in QoL. |

This analysis of data from a real-world survey quantified the impact of FL across five European countries and the United States to investigate differences across countries and the effects on patient QoL compared with a non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) reference population across treatment lines. |

What was learned from the study? |

While FL is perceived as an indolent disease, patients with FL who typically experience remissions and relapses throughout their life span have high unmet needs regarding QoL. |

In general, patients with FL had worse QoL than those of the NHL reference population, with most aspects of QoL being significantly worse at later lines of therapy compared to earlier lines. Differences were identified across countries, as functioning and, symptoms were worse for patients in Europe (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom) than the United States. |

These real-world findings highlight the need for novel FL therapies that maintain/ improve QoL and alleviate patient burden. |

Introduction

The indolent B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder follicular lymphoma (FL) is the second most common type of lymphoma in Western Europe and the United States (US) [1,2], accounting for approximately 30–35% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) [2,3].

FL is heterogeneous, and typically has a long natural course of remissions and relapses. The disease is therefore generally considered a chronic, life-long condition [1]. The 5-year relative survival rate is 90.6% [4], although is significantly worse for patients with transformation [5]. Most patients with FL will have a prolonged survival with or without treatment [6,7], with overall survival potentially extending beyond 20 years [8]. It is therefore important to consider quality of life (QoL) when deciding a suitable treatment. Symptoms such as fatigue [9,10] can significantly impact QoL in patients with FL [11], and treatment can have an even greater negative impact on the patient than the disease itself [12].

The treatment landscape for NHLs was changed immensely by the introduction of immunotherapies. The anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab, plus chemotherapy for induction followed by maintenance therapy, has resulted in improved outcomes for patients with FL [13,14,15,16]. More recently, autologous chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy that targets lymphoma-associated antigens, such as CD19, has demonstrated significant clinical efficacy, and prolonged responses in chemotherapy-refractory patients [17,18,19]. Bispecific antibodies that concurrently bind target tumor cells and immune effector cells have also improved treatment responses in patients with refractory tumors [20,21].

The safety profiles of CAR T cells and bispecific antibodies have generally been acceptable and manageable [20,22], although there is the potential for serious adverse events related to immune system overactivation, including cytokine-release syndrome and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome [20,23].

There remains a paucity of data evaluating real-world, patient-reported outcomes and QoL in FL. Considering the seemingly indolent disease progression of FL due to its chronic relapsing–remitting nature, it is important to understand patient-reported QoL, as disease- and treatment-related symptoms and disease activity have a long-term impact on patients. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) may also differ according to patients’ disease stage and whether they are in remission. A study in patients with FL found that patients who had relapsed were more likely to experience worse QoL than patients who were newly diagnosed, in remission, or disease-free [12].

To address the information gap, we aimed to quantify the impact of FL on patients’ QoL, and to investigate QoL differences across treatment lines, geographic regions, and countries, using data from a multinational, real-world survey in five European countries and the United States (US).

Methods

Survey Design

Data were drawn from the Adelphi Real World (ARW) FL Wave II Disease Specific Programme™ (DSP™), a cross-sectional survey with elements of retrospective data collection of physicians and their patients in Europe [France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom (UK)] and the US from June 2021 to January 2022. The methodology has been previously described, validated, and demonstrated to be representative and consistent over time [24,25,26,27], and is well-established with surveys in many different disease areas implemented globally [28,29,30,31].

Physicians completed online surveys and patient record forms (PRF) for the next six consecutively consulting patients (one patient on first-line therapy [1L], three patients on second-line therapy [2L], and two patients on third-line therapy and beyond [3L+)]. Each record included details regarding patient demographics and clinical characteristics such as ECOG score and Ann Arbor staging at data collection. Physicians completed the record using a combination of existing patient clinical records, their own judgement and diagnostic/interpretation skills, and information collected during the consultation.

Each patient for whom a physician completed a PRF were then invited to voluntarily fill out a pen-and-paper patient self-completion form (PSC). The PSC included detailed questions on patient demographics, functioning, and symptoms via the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) [32,33,34].

Data were collected in such a way that patients and physicians could not be identified directly. Physician and patient data were pseudo-anonymized. A code was assigned when data were collected. Upon receipt by ARW, data were pseudo-anonymized again to mitigate against tracing them back to the individual. Data were aggregated before being shared with the subscriber and/or for publication.

Survey Population

A geographically representative sample of physicians were recruited to participate in the DSP. Physicians were eligible to participate in this survey if they were medical oncologists, hematologists, or hem-oncologists. Physicians had to be personally responsible for treatment decisions and management of patients with FL, and for making treatment decisions for at least four patients with FL in a typical month.

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were over the age of 18 years at the time of data collection, had a physician-confirmed diagnosis of FL, and were receiving active drug treatment for FL at the time of data collection. Patients were excluded if they were participating in a clinical trial. Steroid monotherapy was not considered to be an active drug treatment.

Survey Measures

The EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire comprises a global health status/quality of life (GHS/QoL) scale, five functional scales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive, and social functioning), eight symptom scales (fatigue, nausea/vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, and diarrhea) and a financial difficulties scale. Scale scores are linearly converted to range from 0 to 100. For the functioning and GHS/QoL scales, higher scores indicate better functioning. For the symptom and financial difficulties scales, higher scores indicate worse symptom burden and greater financial difficulties, respectively [32,34].

Survey Ethics and Consent

This research complied with all relevant market research guidelines and legal obligations, and data were collected according to European Pharmaceutical Marketing Research Association guidelines [35].

The survey was conducted in accordance with the Pearl Institutional Review Board (protocol number 9061). Where patients provided data directly, they signed an informed consent form prior to participation in this study. Each survey was performed in full accordance with relevant legislation at the time of data collection, including the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act 1996 [36] and Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act legislation [37].

Physician participation was financially incentivized, with reimbursement upon survey completion according to fair market research rates.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed only where physician- and patient-reported data were matched, i.e., in cases where both PRFs and PSCs, respectively, were completed. Data were analyzed by country (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, UK, US) and region (Europe, US), summarized using descriptive analyses, and compared using bivariate analyses. Means and standard deviations (SD) and medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) were calculated for continuous variables, and frequency and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. Missing data were not imputed; therefore, the base of patients for analysis could vary from variable to variable and was reported separately for each analysis. EORTC QLQ-C30 scores for Europe were compared to the US using a t test. EORTC QLQ-C30 scores for each country were compared to the other countries using a t test and across-all-countries analysis of variance statistical tests were performed. Statistical analysis was performed in Stata 17.

Using a t test, patient EORTC QLQ-C30 scores from our survey were compared against validated EORTC QLQ-C30 NHL reference scores [34], which summarize QoL for patients with NHL. This allows for an understanding of DSP patients with FL relative to a general patient population with NHL. Descriptive and bivariate analyses were performed to compare QoL (per EORTC QLQ-C30) across line of therapy (LOT) (1L vs. 2L, 1L vs. 3L+ , and 2L vs. 3L+). A test for trend across lines of therapy was performed using the Jonckheere–Terpstra test. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

All results discussed below regarding disease and symptom burden are statistically significant (p < 0.05), unless stated otherwise.

Physician and Patient Sample Populations

A total of 251 oncologists/hematologists/hem-oncologists completed PRFs for 1478 eligible patients. A total of 401 patients completed a PSC and were included in the analyses. The top three physician reported guidelines across all markets were National Comprehensive Cancer Network (59%), European Society of Medical Oncology (57%), and American Society of Clinical Oncology (55%) (Table 1).

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Mean (SD) age was 66.0 (9.24) years, 58.1% were male, and 62.8% were retired (Table 2). The mean (SD) age of patients in Europe was 66.0 (9.12) years and in the US was 66.1 (9.73) years. The proportion of males in the European cohort was 55.7% and in the US cohort was 66.7%. In Europe, 8.9% of patients were working full/part-time, whereas, in the US, 25.3% were working full-/part-time.

Almost two-thirds (64.8%) of patients with FL had Ann Arbor stage III (41.9%) or stage IV (22.9%) disease at data collection. Ann Arbor stage III and stage IV were reported for 44.3% and 18.5% of patients in Europe, respectively, versus 33.3% and 39.1% in the US. Overall, 20.0% and 61.1% of patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG-PS) score of 0 and 1, respectively. Patients’ level of functioning in terms of their ability to care for themself, daily activity, and physical ability varied widely among the six countries. An ECOG-PS score of 0 or 1 was observed in 79.9% of patients in Europe (ranging from 65.0% in Germany to 95.3% in Italy) and in 85.1% in the US. An ECOG-PS score of 2 or 3 was reported for 20.1% of patients in Europe (ranging from 4.9% in France and 4.8% in Italy to 35.0% in Germany) and for 14.9% of patients in the US. A Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index-2 (FLIPI-2) score of 2 (indicating intermediate risk) was observed in 38.5% of patients with FL, whereas 37.0% had a score of 3–5 (indicating high risk). In the US, a higher percentage of patients with FL had a high risk FLIPI-2 score (42.3%) compared to those 36.4% across Europe (ranging from 30.5% in Italy to 42.5% in Germany).

At data collection, 48.4% of patients were receiving 2L treatment and 76.1% were receiving 2L+ treatment. Over one-quarter (27.7%) of patients were receiving 3L+ therapy. The top three treatments received at 1L induction therapy were R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone), R-bendamustine (rituximab, bendamustine) and rituximab (60.6%, 10.0%, and 5.5%, respectively). At 2L induction therapy, the top three treatments received were R-bendamustine, O-bendamustine (obinutuzumab and bendamustine), and R-CHOP [25.9%, 18.4%, and 14.1%, respectively]. At 3L induction therapy, the top three treatments received were idelalisib (18.0%), rituximab + lenalidomide (17.1%), and obinutuzumab + lenalidomide (12.6%) (Table 2). Overall, patients in Europe were more likely to be receiving later lines of therapy than in the US, with 80.3% and 60.9% of patients receiving 2L+ treatment, respectively. In the US, 13.2% of patients were receiving CHOP + obinutuzumab (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone) for 2L induction therapy, with 20.8% of patients having received R-bendamustine. In Europe, 27.0% of patients with FL received R-bendamustine for 2L induction therapy with 20.6% having received O-bendamustine.

A total of 59.9% of patients with FL received supportive therapies to treat their FL or any other concomitant conditions. Across Europe, this was 66.9% of patients compared to 34.5% in the US. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factors (G-CSFs) were used by 25.0% of patients with FL. In the US, usage of G-CSFs in patients with FL was 3.3%, compared to 28.1% usage in Europe.

Forty-four percent of patients with FL were diagnosed between 0 and 2 years before the time of data collection and 24.3% of patients were diagnosed between 2 and 4 years before the time of data collection (Table 2). On average (SD), those who were receiving 1L treatment at time of data collection started their treatment 162.3 (200.45) days before the time of data collection. For 2L, this decreased to 145.3 (186.47) days, while for 3L, it decreased to 113.0 (128.00) days before the time of data collection (Table 2).

Disease Burden and Patient-Reported EORTC QLQ-C30

Mean EORTC Scores by Study Regions and Countries

The mean (SD) score for GHS/QoL in the FL DSP population across all markets was 51.8 (20.06), ranging from 50.1 (18.90) in Europe to 57.6 (22.99) in the US (Supplementary Table S1).

US scores for GHS/QoL and all functioning domains were higher and almost all symptom domains (excluding diarrhea) were lower versus all other European countries (Supplementary Table S2). The mean (SD) German GHS/QoL score was lower compared to the other countries [41.3 (13.91) vs. 54.8 (18.00) France, 51.9 (13.39) Italy, 59.6 (22.79) Spain, 55.4 (19.07) UK, and 57.6 (22.99) US; Supplementary Table S2]. The UK and Spain had higher scores for GHS/QoL, physical, role, and social (UK only) functioning compared to all other countries, while Italy had lower scores for emotional, cognitive, and social functioning. In Germany, almost all functioning scores (excluding cognitive functioning) were lower, and almost all symptom scores (excluding constipation) and financial difficulties were higher versus all other countries. France was not significantly different from all other countries in any of the functions, symptoms, or GHS/QoL.

Mean EORTC scores vs the NHL Reference Value Mean Scores

The mean (SD) score for GHS/QoL in the FL DSP population was worse when compared with NHL reference value [51.8 (20.06) vs. 56.1 (27.1); Table 3]. Mean (SD) functioning scores for role, cognitive, and social functioning in FL DSP patients were better than those of the NHL reference values [62.7 (27.55) vs. 57.3 (36.2), 74.4 (22.61) vs. 68.5 (30.8), and 65.8 (26.22) vs. 60.4 (34.1)], respectively. However, interestingly, mean (SD) symptom scores were significantly worse in FL DSP patients compared to the NHL reference values with regard to nausea and vomiting [17.6 (20.13) vs. 10.0 (28.9)], pain [27.9 (25.71) vs. 24.5 (30.1)], dyspnea [26.0 (28.32) vs. 16.9 (24.6)], appetite loss [33.2 (28.23) vs. 30.7 (31.5)], and diarrhea [15.3 (22.37) vs. 9.5 (19.1)].

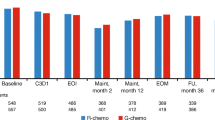

Mean EORTC Scores Across Lines of Therapy

In our study, mean (SD) scores for GHS/QoL [[56.5 (22.21) to 50.4 (20.11)] and for all functioning domains (excluding emotional functioning) worsened from 1 to 3L+ , with the worsening across lines of therapy in physical functioning [77.9 (18.36) to 66.2 (20.70)], role functioning [72.7 (23.59) to 57.1 (27.48)], and social functioning [70.1 (24.89) to 61.0 (28.38)] reaching statistical significance for the trend (Table 4). Mean (SD) scores for fatigue [35.1 (21.53) to 44.7 (22.55)], pain [22.2 (23.40) to 32.1 (26.37)], and dyspnea [20.5 (25.76) to 30.3 (30.14)], all worsened across the lines of therapy from 1 to 3L+, reaching statistical significance for trend (Table 4).

Pairwise Analysis of Mean EORTC Scores between Lines of Therapy

Mean scores for GHS/QoL and all functioning/symptom scales for all therapy lines are shown in Table 5. Mean (SD) score for GHS/QoL at 2L was 50.4 (18.72) worse than at 1L [56.5 (22.21)], there were no differences between 1 and 3L [50.4 (20.11)] and 2L and 3L. Physical functioning was the only domain to consistently have mean (SD) scores differing significantly between the lines of therapy, with scores at 2L worse than at 1L [71.4 (19.57) vs. 77.9 (18.36)], scores at 3L+ worse than at 2L [66.2 (20.70) vs. 71.4 (19.57)], and scores at 3L+ worse than at 1L [66.2 (20.70) vs. 77.9 (18.36)].

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed real-world data from a multinational survey of patients with FL, exploring PROs and QoL in patients receiving 1L, 2L, and 3L+ therapy. We found that GHS/QoL was generally poor among patients with FL, with patients in our study reporting significantly worse mean scores than a reference population of patients with NHL. Similarly, we found most symptom scores were worse in patients with FL compared with those with NHL, including, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnea, appetite loss, and diarrhea. The functioning and symptom burden in patients with FL generally worsened with successive LOT.

Other studies in Europe reported similar findings, with a study conducted by Johnsen et al. also reporting poor mean GHS/QoL and citing dyspnea, among other symptoms, as one of the most prevalent symptoms cited by patients with FL [38]. Of note, the mean GHS/QoL we reported here was even lower than was found in the study by Johnsen et al., by around five units across several of the functional and symptom scales. Five units is the minimal clinically important difference for EORTC QLQ-C30 reported in a study across several tumor types [39], suggesting that the patients in our study had a perceptibly worse QoL than those studied by Johnsen et al. A study in Germany focused on the effect of treatment on QoL in patients with FL reported that QoL was low in all patients, but that patients with FL receiving rituximab and chemotherapy had worse QoL than patients receiving high-dose chemotherapy followed by peripheral blood stem cell transplantation [40]. Taken together, these findings suggest that both the burden of the disease and the side effects of treatment can lead to poor QoL in patients with FL, highlighting the need for novel therapies and improvements in supportive care interventions that may maintain or improve QoL.

The recurring nature of FL means that patients are generally treated with multiple LOT during their treatment journey. A large proportion of patients with FL in our study were receiving 2L and 3L+ therapy, with many reporting worse overall GHS/QoL across successive LOT. Similarly, symptom burden in patients with FL was observed to be higher in later LOT on several key scales (fatigue, pain, and dyspnea). Previous studies exploring other patient outcomes have also demonstrated an effect of LOT, finding that progression-free survival and overall survival diminished across LOT [41,42]. Our findings are similar to those in patients with other cancers, with studies on patients with multiple myeloma in Germany and France finding those receiving later LOT had lower QoL compared with patients earlier in their treatment journey [43,44]. There are likely to be multiple reasons for a decrease in QoL with successive LOT, for example, patients on later LOT have likely had their disease and the side effects of their treatment for longer, as well as experiencing disease progression and increase in age over successive therapies, all of which may decrease patients’ overall QoL [43]. One solution to improve QoL for patients on later lines of therapy could be for physicians to prescribe a better supportive therapy in conjunction with chemotherapy. For example, the use of a granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) administered during chemotherapy treatment has been found to reduce the risk of infection, including febrile neutropenia and pneumonia, complications often resulting from chemotherapy [45,46]. As a result of receiving a G-CSF, patients had fewer hospitalizations and fewer days in hospital compared with patients not receiving this therapy [45].

In contrast to our other results on patient QoL across LOT, we found that EORTC QLQ-C30 emotional functioning scores in patients with FL were not significantly different between LOT. A possible explanation for this may be that receiving therapy, irrespective of which line it is, may help to reduce patient anxiety and/or depression and allow them to feel more in control of and hopeful about fighting their disease [6,10]. Improving knowledge of individual patient genetic and epigenetic profiles could help to identify those patients at high risk for transformation and disease progression earlier. This may help to better target therapies to achieve longer remission and reduce the number of LOT patients receive [47], maintaining or improving patients’ QoL.

Our analysis showed that the GHS/QoL of patients with FL differed significantly across countries in numerous EORTC functioning and symptom domains, with patient QoL reported as significantly worse in Europe compared with QoL in the US. We also found differences between the five European countries included in the study, with QoL in Germany reported as significantly lower and QoL in Spain and the UK being significantly higher compared to the other countries examined. Regional and country differences may reflect differences in populations and healthcare systems across countries; however, further research is needed to elucidate the reasons for country differences.

The limitations of DSP surveys have been previously described in other real-world studies using DSP data [25,30,48,49]. Several limitations should be considered in the evaluation of our findings. Patients participating in the surveys may not reflect the general FL population, as a certain number of patients were recruited for each disease severity category to ensure that the sample size in each was sufficient to fulfil the quota of the study. Similarly, we only included physicians in the study who were treating more than four patients monthly, which may have led to our data coming from busier physicians based in a specific environment, such as academic medical centers or busy urban clinics rather than quieter, more rural settings. For some countries in the study, we had relatively lower patient numbers, particularly in France, Italy, and the UK. This may have contributed to the variation in individual country outcomes and differences between countries in patient demographics and clinical characteristics. These differences in sample sizes across countries may also have led to observed differences in QoL across Europe versus the US. The analyses did not control for individual patient characteristics and treatment. It should be noted that the survey did not analyze the therapies received across the different stages of FL therefore future research should investigate this. It should also be noted that the survey did not include patients with FL who had transformed from an indolent form to a more aggressive form. However, transformation rates are low, with estimates of 2–3% of patients annually in the rituximab era [5,50], and future research could benefit from including transformed patients with the FL population. This study only included patients who were actively receiving treatment at the time of data collection, therefore, patients who were on a “watch and wait” period were not included. The minority of patients undergo watch and wait [41]; however, future research could include this patient subset for comparison in their analyses. The data included here were from the six countries that were the focus of this study, and therefore results may not be representative of patients with FL in other countries not included in this study. For better understanding of real-world QoL in patients with FL on a larger scale, future surveys should ensure data are more reflective of epidemiology internationally, beyond the six countries included here. Future research should compare the baseline characteristics of patients who completed versus patients who did not complete the patient self-completion questionnaire, and evaluate the reasons for non-completion to assess any biases that may exist in the results reported in this study.

Data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, during which treatment may have been adjusted to accommodate the restrictions imposed on the populations across the different countries. Moreover, QoL and functioning, particularly emotional and social well-being, may have been affected, being influenced by the living environment and access to healthcare during the pandemic. The findings may therefore be different from those if data had been collected pre- and/or post-pandemic.

Conclusions

Although FL is perceived as an indolent disease, patients have high unmet needs in their QoL, based on comparisons with NHL reference values. Furthermore, patient QoL decreases with subsequent LOT and may be worse in Europe than in the US. Maintaining QoL for patients with FL is an important factor in treatment decision-making, given the likelihood of many years of survival and multiple LOT. Our findings help address the patient-reported QoL data gap in FL treatment outcomes, and add to previously published physician-reported efficacy evidence. These findings highlight the need for novel FL therapies and supportive care interventions that increase QoL and alleviate patient burden. In light of the differences from NHL using the general GHS/QoL instrument, EORTC QLQ-C30, there is also the need for a FL-specific instrument for measuring QoL in these patients. Moreover, considering the paucity of data evaluating the patient with FL population, the FL data presented here may provide a benchmark to compare against, and can support future research into the impact of novel agents on clinical trial-assessed QoL.

Data Availability

All data that support the findings of this study are the intellectual property of Adelphi Real World and so are not publicly available. Data are however available upon reasonable request and with permission of Adelphi Real World (contact Neil.milloy@adelphigroup.com).

References

Dreyling M, Ghielmini M, Rule S, et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed follicular lymphoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(3):298–308.

Freedman A, Jacobsen E. Follicular lymphoma: 2020 update on diagnosis and management. Am J Hematol. 2020;95(3):316–27.

Kaseb H. AMA, Koshy N. V. Follicular Lymphoma 2022 [Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538206/. Accessed 12 Apr 2024.

National Cancer Institute. Cancer Stat Facts: NHL—Follicular Lymphoma: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program; 2020 [Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/follicular.html. Accessed 12 Apr 2024.

Wagner-Johnston ND, Link BK, Byrtek M, et al. Outcomes of transformed follicular lymphoma in the modern era: a report from the National LymphoCare Study (NLCS). Blood. 2015;126(7):851–7.

Ardeshna KM, Qian W, Smith P, et al. Rituximab versus a watch-and-wait approach in patients with advanced-stage, asymptomatic, non-bulky follicular lymphoma: an open-label randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(4):424–35.

Bachy E, Seymour JF, Feugier P, et al. Sustained progression-free survival benefit of rituximab maintenance in patients with follicular lymphoma: long-term results of the PRIMA Study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(31):2815–24.

Cartron G, Trotman J. Time for an individualized approach to first-line management of follicular lymphoma. Haematologica. 2022;107(1):7–18.

Nastoupil L, Sinha R, Hirschey A, Flowers CR. Considerations in the initial management of follicular lymphoma. Community Oncol. 2012;9(11):S53–60.

Webster K, Cella D. Quality of life in patients with low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Oncology (Williston Park). 1998;12(5):697–714.

Kiserud CE, Lockmer S, Baerug I, et al. Health-related quality of life and chronic fatigue in long-term survivors of indolent lymphoma - a comparison with normative data. Leuk Lymphoma. 2023;64(2):349–55.

Pettengell R, Donatti C, Hoskin P, et al. The impact of follicular lymphoma on health-related quality of life. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(3):570–6.

Hiddemann W, Kneba M, Dreyling M, et al. Frontline therapy with rituximab added to the combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) significantly improves the outcome for patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma compared with therapy with CHOP alone: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2005;106(12):3725–32.

Marcus R, Imrie K, Belch A, et al. CVP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CVP as first-line treatment for advanced follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2005;105(4):1417–23.

Rummel MJ, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G, et al. Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9873):1203–10.

Salles GA, Seymour JF, Feugier P, et al. Updated 6 year follow-up of The PRIMA study confirms the benefit Of 2-year rituximab maintenance in follicular lymphoma patients responding to frontline immunochemotherapy. Blood. 2013;122(21):509.

Abramson JS, Palomba ML, Gordon LI, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel for patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphomas (TRANSCEND NHL 001): a multicentre seamless design study. Lancet. 2020;396(10254):839–52.

Fowler NH, Dickinson M, Dreyling M, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in adult relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma: the phase 2 ELARA trial. Nat Med. 2022;28(2):325–32.

Schuster SJ, Svoboda J, Chong EA, et al. chimeric antigen receptor T cells in refractory B-cell lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(26):2545–54.

Falchi L, Vardhana SA, Salles GA. Bispecific antibodies for the treatment of B-cell lymphoma: promises, unknowns, and opportunities. Blood. 2023;141(5):467–80.

Wei J, Yang Y, Wang G, Liu M. Current landscape and future directions of bispecific antibodies in cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1035276.

Chen X, Li P, Tian B, Kang X. Serious adverse events and coping strategies of CAR-T cells in the treatment of malignant tumors. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1079181.

Adkins S. CAR T-cell therapy: adverse events and management. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2019;10(Suppl 3):21–8.

Anderson P, Benford M, Harris N, Karavali M, Piercy J. Real-world physician and patient behaviour across countries: disease-Specific Programmes – a means to understand. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(11):3063–72.

Babineaux SM, Curtis B, Holbrook T, Milligan G, Piercy J. Evidence for validity of a national physician and patient-reported, cross-sectional survey in China and UK: the Disease Specific Programme. BMJ Open. 2016;6(8): e010352.

Higgins V, Piercy J, Roughley A, et al. Trends in medication use in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a long-term view of real-world treatment between 2000 and 2015. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2016;9:371–80.

Anderson P, Higgins V, Courcy J, et al. Real-world evidence generation from patients, their caregivers and physicians supporting clinical, regulatory and guideline decisions: an update on Disease Specific Programmes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2023;39(12):1707–15.

Leith A, Kim J, Ribbands A, et al. Real-world treatment patterns in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer across Europe (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom) and Japan. Adv Ther. 2022;39(5):2236–55.

Mahtani R, Niyazov A, Lewis K, et al. Real-world study of regional differences in patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and BRCA1/2 mutation testing in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative advanced breast cancer in the United States, Europe, and Israel. Adv Ther. 2023;40(1):331–48.

Molife C, Winfree KB, Bailey H, et al. Patient characteristics, testing and treatment patterns, and outcomes in EGFR-mutated advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a multinational, real-world study. Adv Ther. 2023;40(7):3135–68.

Singh P, Contente M, Bennett B, et al. Real-world treatment patterns and outcomes in patients with head and neck cancer: point-in-time survey of oncologists in Italy and Spain. Adv Ther. 2021;38(9):4722–35.

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual: Brussels, Belgium: EORTC Data Center; 2001 [Available from: https://www.eortc.org/app/uploads/sites/2/2018/02/SCmanual.pdf. Accessed 12 Apr 2024.

Giesinger JM, Kuijpers W, Young T, et al. Thresholds for clinical importance for four key domains of the EORTC QLQ-C30: physical functioning, emotional functioning, fatigue and pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:87.

Scott NW, Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bottomley A, de Graeff A, Groenvold M, Gundy C, Koller M, Petersen MA, Sprangers MAG, on behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Group. EORTC QLQ-C30 Reference Values 2008 [Available from: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.eortc.org/app/uploads/sites/2/2018/02/reference_values_manual2008.pdf. Accessed 12 Apr 2024.

European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association [EphMRA]. Code of Conduct 2019;2020(29 May).

US Department of Health and Human Services. Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. 2003;2020(29 May).

Health Information Technology (HITECH). Health Information Technology Act. 2009;2020(29 May).

Johnsen AT, Tholstrup D, Petersen MA, Pedersen L, Groenvold M. Health related quality of life in a nationally representative sample of haematological patients. Eur J Haematol. 2009;83(2):139–48.

Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(1):139–44.

Andresen S, Brandt J, Dietrich S, Memmer ML, Ho AD, Witzens-Harig M. Quality of life of long term survivors with follicular lymphoma after high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation and conventional chemotherapy. Blood. 2010;116(21):3808.

Batlevi CL, Sha F, Alperovich A, et al. Follicular lymphoma in the modern era: survival, treatment outcomes, and identification of high-risk subgroups. Blood Cancer J. 2020;10(7):74.

Link BK, Day BM, Zhou X, et al. Second-line and subsequent therapy and outcomes for follicular lymphoma in the United States: data from the observational National LymphoCare Study. Br J Haematol. 2019;184(4):660–3.

Despiegel N, Touboul C, Flinois A, et al. Health-related quality of life of patients with multiple myeloma treated in routine clinical practice in France. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019;19(1):e13–28.

Engelhardt M, Ihorst G, Singh M, et al. Real-world evaluation of health-related quality of life in patients with multiple myeloma from Germany. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021;21(2):e160–75.

Cerchione C, De Renzo A, Di Perna M, et al. Pegfilgrastim in primary prophylaxis of febrile neutropenia following frontline bendamustine plus rituximab treatment in patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a single center, real-life experience. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(3):839–45.

Picardi M, Giordano C, Della Pepa R, et al. Correspondence in reference to previously published manuscript: "Faouzi Djebbari et al. Efficacy and infection morbidity of front-line immuno-chemotherapy in follicular lymphoma. Eur J Haematol. 2020; 105: 667-671”. Eur J Haematol. 2021;106(5):734–6.

Matasar MJ, Luminari S, Barr PM, et al. Follicular lymphoma: recent and emerging therapies, treatment strategies, and remaining unmet needs. Oncologist. 2019;24(11):e1236–50.

Holdsworth EA, Donaghy B, Fox KM, et al. Biologic and targeted synthetic DMARD utilization in the United States: adelphi real world disease specific programme for rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Ther. 2021;8(4):1637–49.

Zhao H, Xiao Z, Zhang L, et al. Real-world treatment patterns and outcomes among patients with episodic migraine in China: results from the adelphi migraine disease specific programme. J Pain Res. 2023;16:357–71.

Welaya K, Casulo C. Follicular lymphoma: redefining prognosis, current treatment options, and unmet needs. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33(4):627–38.

Acknowledgements

Patient involvement in completion of questionnaires was voluntary. The authors wish to thank those patients completing the questionnaire for their involvement in the study.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance. Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Sue Libretto, PhD, of Sue Libretto Publications Consultant Ltd (Hertfordshire, UK) on behalf of Adelphi Real World, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guideline.

Funding

This publication (including the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access fee) were sponsored by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Tarrytown, NY, USA. Data collection was undertaken by Adelphi Real World as part of an independent survey, entitled the Adelphi Real World follicular lymphoma Disease Specific Programme (DSP). Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., did not influence the original survey through either contribution to the design of questionnaires or data collection. The analysis described here used data from the DSP. The DSP is a wholly owned Adelphi product. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. are one of multiple subscribers to the DSP.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Tarrytown, NY, USA subscribed to this DSP and were involved in the analyses, design, and editing of the manuscript. Survey design, data collection, data analysis, statistical analyses, data interpretation, and editing were performed by Adelphi Real World. Patrick Connor Johnson, Abigail Bailey, Qiufei Ma, Neil Molloy, Emilia Biondi, Ruben G. W. Quek, Sarah Weatherby, and Sophie Barlow all had access to the aggregated data, provided critical feedback, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

P. Connor Johnson: Works at the Cancer Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA, and a consultant for AstraZeneca Plc, Seagen, ADC Therapeutics, Incyte, Abbvie, BMS and Research Medically Home; Qiufei Ma: Employee of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc, Tarrytown, NY, USA, and has ownership interest in Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc.; Ruben G.W Quek: is an employee of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Tarrytown, NY, USA, and has ownership interest in Amgen Inc., Pfizer Inc., and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc.; Abigail Bailey, Neil Milloy, and Emilia Biondi: Employees of Adelphi Real World and paid consultants to Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc in connection with the development of this manuscript.

Ethical Approval

The survey was conducted in accordance with the Pearl Institutional Review Board (protocol number AG8980). Where patients provided data directly, they signed an informed consent form prior to participation in this study. Each survey was performed in full accordance with relevant legislation at the time of data collection, including the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act 1996 [36] and Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act legislation [37]. Physician participation was financially incentivized, with reimbursement upon survey completion according to fair market research rates.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Johnson, P.C., Bailey, A., Ma, Q. et al. Quality of Life Evaluation in Patients with Follicular Cell Lymphoma: A Real-World Study in Europe and the United States. Adv Ther (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-024-02882-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-024-02882-1