Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) constitutes a major global health burden and is the third leading cause of death worldwide. A high proportion of patients with COPD have cardiovascular disease, but there is also evidence that COPD is a risk factor for adverse outcomes in cardiovascular disease. Patients with COPD frequently die of respiratory and cardiovascular causes, yet the identification and management of cardiopulmonary risk remain suboptimal owing to limited awareness and clinical intervention. Acute exacerbations punctuate the progression of COPD in many patients, reducing lung function and increasing the risk of subsequent exacerbations and cardiovascular events that may lead to early death. This narrative review defines and summarises the principles of COPD-associated cardiopulmonary risk, and examines respiratory interventions currently available to modify this risk, as well as providing expert opinion on future approaches to addressing cardiopulmonary risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This narrative review defines cardiopulmonary risk as the risk of serious respiratory and/or cardiovascular events in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). |

Many people with COPD are at elevated cardiopulmonary risk, which may lead to early death. |

Current evidence supports proactive therapeutic intervention to prevent exacerbations, reduce the risk of cardiopulmonary events and thereby reduce mortality in patients with COPD. |

Reframing the management of COPD towards proactive cardiopulmonary risk reduction could transform the standard of care and, therefore, improve clinical outcomes. |

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) constitutes a major international health burden, with an estimated global prevalence of 10.3%, corresponding to 391.9 million cases in people aged 30–79 years [1, 2]. Furthermore, COPD is the third leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for 3.23 million deaths in 2019 [3], with annual global deaths projected to increase to over 7 million by 2060 [4].

The prevalence of diagnosed cardiovascular disease is estimated to be between 28 and 70% in patients with COPD—two- to five-fold higher than in those without COPD [5,6,7]. Collective risk factors, including but not limited to smoking and advanced age, contribute to this level of coexistence [5, 8, 9]. Yet, the association between COPD and cardiovascular disease remains even after adjustment for these factors [10]. This indicates a syndemic occurrence, where shared risk factors, fundamental pathobiological and pathophysiological interactions and social determinants of health cause an aggregation of the two diseases and exacerbate the burden and prognosis of disease [11].

Patients with COPD are at elevated risk of respiratory and cardiovascular events that may lead to early death [12,13,14,15]. Herein, for COPD, such respiratory events include exacerbations, and cardiovascular events include myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure decompensation and arrhythmia. Respiratory and cardiovascular events are recognised as common causes of death in patients with COPD, with the predominant underlying cause of death varying according to disease severity [16]. Compared with respiratory-related deaths, cardiovascular-related deaths are more prevalent in patients with Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) classification mild and moderate disease (group 1 and 2), with respiratory deaths more prevalent in patients with GOLD classification severe and very severe disease (group 3 and 4) [16]. Notably, modelled projections of cause-specific deaths for patients with COPD in the UK predict higher mortality rates from cardiovascular causes than respiratory causes over a 10-year period [17].

Understanding the extent and nature of respiratory and cardiovascular events in patients with COPD and identifying approaches to reduce the risk of such occurrences is central to improving clinical outcomes. In this narrative review, we examine the current evidence regarding respiratory and cardiovascular outcomes in COPD from which we have derived the concept of cardiopulmonary risk, consider respiratory therapeutic interventions that may reduce this risk and highlight the need for a preventative approach to address cardiopulmonary risk. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Definition of Cardiopulmonary Risk

A standardised definition of cardiopulmonary risk in COPD has yet to be established. We propose a foundational basis for the use of the term cardiopulmonary risk, defined as:

‘The risk of serious respiratory and/or cardiovascular events in patients with COPD. These include, but are not limited to, COPD exacerbations, myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure decompensation, arrhythmia and death due to any of these events.’ |

While myocardial infarction and stroke have standard definitions, here arrhythmia is defined as atrial and ventricular tachyarrhythmia [18,19,20].

Factors Elevating COPD-Associated Cardiopulmonary Risk

There is an expanding evidence base to suggest that COPD is an independent predictor for cardiovascular disease [6, 21,22,23]. A meta-analysis of observational studies demonstrated that patients with COPD have an increased prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension and diabetes [5]. Furthermore, a population-based retrospective cohort study in Canada demonstrated that compared with patients without COPD, there was a 25% increase in the rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE; hazard ratio [HR] 1.25; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.23, 1.27) in a COPD population without a history of cardiovascular disease after adjustment for traditional cardiovascular risk factors [10]. An editorial that evaluated these data recommended that COPD itself is recognised as a distinct cardiovascular risk factor [6]. Moreover, a nationwide UK incident COPD cohort study found that the observed 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease was 52% higher than that predicted by a widely used cardiovascular risk score tool (QRISK3), indicating a considerable and distinct contribution of COPD to cardiovascular disease risk irrespective of traditional cardiovascular risk factors [24]. Thus, while the importance of traditional cardiovascular risk factors and the optimisation of treatment for cardiovascular diseases according to their guidelines is acknowledged, here we will primarily focus on the influence of symptoms and exacerbations on cardiovascular risk in COPD.

Exacerbations of COPD can irreversibly reduce lung function, accelerate the rate of subsequent exacerbations and increase the risk of death [25, 26]. Approximately 50% of patients die within 3.6 years of their first severe (hospitalised) exacerbation [26], and there is an 80% increase in the risk of death in patients who have experienced two moderate (community-treated) exacerbations within the previous year [15]. There is growing evidence of a pathobiological and pathophysiological impact of exacerbations that extends beyond the lungs. Exacerbations amplify the risk of cardiovascular events, and this risk may remain elevated for up to a year [14, 27]. A recent meta-analysis of six cohort studies amounting to 533,672 patients with COPD found that, compared with no exacerbation, the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke at between 1 and 3 months after an exacerbation was increased by over two-fold and approximately 70% respectively (risk ratio [RR] 2.43, 95% CI 1.40, 4.20; and RR 1.68, 95% CI 1.19, 2.38) [28]. The multinational EXACOS-CV programme investigated the risk of cardiovascular events following COPD exacerbations using a set of retrospective longitudinal cohort studies [29]. Data from the UK cohort showed that, compared with no exacerbation, there was a three-fold increase in cardiovascular events (defined as acute coronary syndrome, arrhythmia, heart failure, ischaemic stroke and pulmonary hypertension) within 1–14 days following an exacerbation of any severity, with the risk remaining elevated for up to and beyond 1 year [30]. This elevated risk was highest in the 2 weeks immediately after a severe exacerbation (adjusted HR 14.5; 95% CI 12.2, 17.3) and 14–30 days after a moderate exacerbation (adjusted HR 1.94; 95% CI 1.63, 2.31) [30]. Notably, when scaling the findings to the wider COPD population, approximately 28% of severe exacerbations and 22% of moderate exacerbations result in a cardiovascular event [30]. When considering individual cardiovascular components of the composite outcome, the UK cohort reported that, compared with no exacerbation, the incidence rate of heart failure was increased following an exacerbation of any severity and remained significantly elevated across the entire median follow-up period of 2.40 years (adjusted HR 2.33; 95% CI 2.24, 2.42) [30]. Similarly, in the Canadian cohort this increased risk of heart failure was observed up to 180 days following an exacerbation of any severity (adjusted HR 2.25; 95% CI 1.96, 2.59) [31]. Indeed, overall data from European and Canadian cohorts reported similar outcomes to the UK cohort, demonstrating that compared with no exacerbation, there was a heightened risk of severe cardiovascular events (defined as acute coronary syndrome, arrhythmia, heart failure and ischaemic stroke) or death within the first 7 days after a severe exacerbation (adjusted HR 15.84; 95% CI 15.26, 16.45 to HR 48.57; 95% CI 36.88, 63.96 across countries), which was sustained beyond 1 year, and for up to 6 months following a moderate exacerbation [31,32,33]. These findings are further supported by a post hoc analysis of the IMPACT study, which reported that the overall risk of cardiovascular events was higher during moderate and severe exacerbations, and remained elevated for 30 days post-exacerbation, even in patients of low cardiovascular risk [34]. Although no studies to date have investigated the association of cardiovascular events and subsequent exacerbation frequency and severity in people with COPD, the presence of cardiovascular disease in patients with COPD is reported to increase the frequency of exacerbations [35], cardiovascular-related hospitalisation and mortality [36, 37].

Prognostic markers of future exacerbations are established in the literature. A history of exacerbations is the single strongest independent predictor for future exacerbations [38], although it is important to recognise that the frequency of exacerbations may vary markedly from year to year within individual patients [39]. Complex, multivariable risk prediction models that include several prognostic risk factors have superior predictive performance compared with exacerbation history alone and may have future clinical utility [40], though such risk stratification tools are often not employed in routine clinical practice [41]. When risk is evaluated in patients with COPD, typically only the risk of an exacerbation is assessed and cardiovascular risk is overlooked [42].

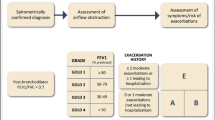

Symptoms such as increased dyspnoea and frequent productive cough predict subsequent exacerbation risk. In a retrospective observational cohort study, ~ 1 in 2 patients with a Medical Research Council (MRC) grade of ≥ 3 experienced an exacerbation in the following 12 months [43]. Similarly, in a prospective observational study, patients with frequent productive cough at baseline had twice the risk of hospital admission for exacerbation within the following 12 months [13] and a 39% increased risk of a major adverse cardiovascular or respiratory event over 3 years of follow-up [44]. The totality of these cardiopulmonary interactions and events punctuates and accelerates the progression of COPD along an adverse prognostic trajectory (Fig. 1).

COPD-associated cardiopulmonary risk. Arrow type and shade indicate strength of association: strong association, with substantial supporting data (dark grey solid), emerging association, with some supporting data (dark grey dotted), suspected association, with data yet to be generated (light grey dotted). COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Mechanisms

The precise mechanisms driving cardiopulmonary events in COPD are yet to be fully elucidated. We propose exacerbations as a foundational risk factor for respiratory and cardiovascular events that are associated with, and may amplify, underlying mechanisms already present in COPD including systemic inflammation, hyperinflation and hypoxaemia. This is based on our knowledge that lung inflammation may trigger systemic inflammation, resulting in atherothrombosis [45]. Additionally, hyperinflation hinders cardiac output and oxygenation [46, 47], and hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction can cause pulmonary hypertension [48], which can result in right ventricular dysfunction and reduced cardiac output [49].

Reducing COPD-Associated Cardiopulmonary Risk

Exacerbation Risk Reduction

Both mono and dual long-acting bronchodilator therapies have shown evidence of exacerbation reduction. The UPLIFT study reported a significant reduction in the risk of exacerbations with long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) monotherapy versus placebo [50], and the POET-COPD study demonstrated that LAMA monotherapy has greater efficacy versus long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) monotherapy on exacerbation prevention [51]. When evaluated in combination in the FLAME study, LAMA/LABA dual therapy was associated with a reduction in exacerbations compared with an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)/LABA dual therapy [52]. There is also good evidence for exacerbation reduction with ICS/LABA dual therapy, which has shown greater efficacy in reducing exacerbations than LAMA/LABA dual therapy, including in the IMPACT and ETHOS studies [53, 54]. The differences observed between FLAME and the IMPACT and ETHOS studies may be explained by patient population differences, whereby IMPACT and ETHOS included patients at higher risk of exacerbations than the patient population of FLAME [52,53,54]. Overall, the benefit of ICS appears to be greatest in patients at high exacerbation risk [55].

Three different single-inhaler, fixed-dose triple-therapy combinations of ICS/LAMA/LABA have been shown to further reduce exacerbation frequency. A triple-therapy combination (fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol) was evaluated in the 24-week FULFIL and the 52-week IMPACT studies. FULFIL reported a significant reduction in the rate of moderate or severe exacerbations with triple therapy versus ICS/LABA [56], and IMPACT achieved its primary endpoint of reducing moderate or severe exacerbations with triple therapy versus LAMA/LABA and ICS/LABA [53]. The 24-week KRONOS and 52-week ETHOS studies evaluated the efficacy of another triple therapy (budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate) versus the corresponding dual therapies [54, 57]. In KRONOS, triple therapy demonstrated a significant reduction in the rate of moderate or severe exacerbations versus LAMA/LABA [57]. Of note, this study was not enriched for patients with a history of recent exacerbations; 74.4% of the population had no documented moderate or severe exacerbations in the 12 months preceding the study [57]. Further effects of this triple therapy on the rate of exacerbations were demonstrated in the ETHOS study, which met its primary endpoint in reducing the risk of moderate or severe exacerbations versus LAMA/LABA and ICS/LABA [54]. Similarly, a significant reduction in the rate of moderate or severe exacerbations was reported in three 52-week studies, TRILOGY, TRINITY and TRIBUTE, with triple therapy (beclomethasone dipropionate/glycopyrronium/formoterol fumarate) versus the corresponding ICS/LABA dual therapy, a LAMA and a LAMA/LABA dual therapy respectively [58,59,60]. The benefit of treatment with ICS has been shown to be related to blood eosinophil count; post hoc analyses of the IMPACT and ETHOS studies reported greater exacerbation risk reduction in patients with eosinophil levels ≥ 100 cells/μl [61,62,63].

Recent real-world evidence suggests that prompt initiation of triple therapy (within 30 days post exacerbation) may further reduce the risk of future exacerbations compared with delayed (31–180 days) or very delayed (181–365 days) intervention [64, 65].

Cardiovascular Risk Reduction with Inhaled Therapy

Currently, there is a limited body of evidence for inhaled medications reducing cardiovascular events in patients with COPD. A post hoc analysis of the EUROSCOP study found that ICS monotherapy reduced the rate of ischaemic cardiac events compared with placebo [66]. Furthermore, the CLAIM study assessed the effect of dual LAMA/LABA bronchodilator therapy versus placebo on cardiac function, whereby a significant increase in left ventricular end-diastolic volume was reported for LAMA/LABA [67]. These findings are supported by a recent large observational study that reported positive effects on left atrial diameter with long-term ICS, ICS/LABA and particularly LAMA/LABA dual therapy [68]. Conversely, in the SUMMIT study, ICS/LABA had no effect on a composite cardiovascular endpoint (cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, unstable angina and transient ischaemic attack) versus placebo in a population with moderate COPD that was enriched for cardiovascular risk [69].

In both the ETHOS and IMPACT studies, the most common cause of death was cardiovascular [70, 71], and there were numerically fewer cardiovascular deaths reported with triple therapy compared with LAMA/LABA [70, 71]. In ETHOS, a benefit of triple therapy relative to LAMA/LABA was observed for MACE [70]; notably, 42% of the patients who died in ETHOS did not experience a moderate or severe exacerbation during the study [70]. Furthermore, the ETHOS study evaluated triple therapy at two doses (low and high) of the ICS component. Both doses showed comparable effects in reducing exacerbation rates versus LAMA/LABA and ICS/LABA, but only the high-dose treatment arm reduced mortality [54]. In the pooled analysis of TRILOGY, TRINITY and TRIBUTE, there was a reduction in the risk of non-respiratory fatal events with ICS-containing triple therapy versus ICS-free treatments [72]. Together, these findings argue for a treatment benefit on cardiovascular events and death that is not exclusively related to reductions in the rate of exacerbations.

We recognise existing literature suggesting bronchodilator therapies may be associated with increased risk of cardiovascular events. A network meta-analysis reported that, compared with ICS/LABA, LAMA/LABA dual therapy and triple therapy increased MACE in patients with COPD [73]. However, the interpretation of these findings is complex. LAMA/LABA and triple therapy were not reported to increase cardiovascular risk compared with placebo, or LAMA and LABA monotherapies, and fewer cardiovascular deaths were reported for those receiving triple therapy than LAMA/LABA, suggesting a level of ICS-related cardiovascular protection [74]. Additionally, a review of the cardiovascular effects of LAMAs indicated that they do not increase the risk of severe cardiovascular adverse events when compared with other active therapies or placebo [75]. Overall, the benefits of inhaled bronchodilators alone or in combination appear to outweigh any potential risks [74]. Considering the increased risk and burden of cardiovascular events in patients with COPD, there is a need for further studies to test interventions for the prevention of cardiovascular events.

Mortality Risk Reduction

There is evidence to support a reduction in the risk of mortality with select pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. Among the recognised non-pharmacological interventions, smoking cessation is associated with mortality reduction estimates ranging from 32 to 84% compared with continued smoking [76], and early initiation of pulmonary rehabilitation has demonstrated a 42% reduction in mortality [77]. Furthermore, two studies have reported mortality risk reduction with long-term oxygen therapy [78, 79], and the addition of home mechanical ventilation to home oxygen therapy has demonstrated survival benefit [80].

Among pharmacological interventions, fixed-dose combination triple therapy is the only treatment with evidence supporting a reduction in all-cause mortality in patients with COPD. In an analysis of the final retrieved dataset of the IMPACT study, in which all-cause mortality was a prespecified ‘other’ endpoint, there was a reduction in mortality with triple therapy versus LAMA/LABA [53, 71]. Similarly, time to death (all cause) was evaluated as a prespecified secondary endpoint in the ETHOS study, and in an analysis of the final retrieved dataset there was a reduction in mortality with triple therapy versus LAMA/LABA [54, 70]. An analysis of pooled data from the TRILOGY, TRINITY and TRIBUTE studies comparing an ICS-containing triple therapy with ICS-free treatments showed a numerical, but not statistically significant, reduction in the risk of a fatal event [58,59,60, 72].

The effect of ICS/LABA dual therapy versus placebo on all-cause mortality was evaluated as a primary endpoint in the TORCH and SUMMIT studies [69, 81]. Both studies failed to show a statistically significant reduction in all-cause mortality; notably, both trials were unique in including patients without a recent history of exacerbations, and the SUMMIT trial only included those with moderate COPD [69, 81]. A summary of cardiopulmonary outcomes with inhaled therapies is given in Table 1.

Potential Mechanisms of Cardiopulmonary Protection by Inhaled Therapies

Optimising COPD treatment may confer cardiopulmonary protection [82]. ICS could reduce inflammation in the lung [83], and bronchodilators decrease airway resistance and reduce hyperinflation, improving inspiratory capacity, reducing residual volume and potentially improving cardiac function [67, 84, 85]. Both ICS and bronchodilators may improve ventilation-perfusion matching [86,87,88], resulting in less hypoxaemia [86, 87]. These components of triple therapy have shown reductions in exacerbations, with greater benefit in combination [2].

Approaches to Cardiopulmonary Risk Management in COPD

The current approach to COPD management can be regarded as suboptimal, as it is often more reactive than proactive [89]. Moreover, there is a general perception of therapeutic inertia, defined as failure to escalate or initiate adequate therapy when treatment goals are not met [90]. This is compounded by delayed diagnosis of COPD and insufficient awareness of cardiopulmonary risk.

Although the ETHOS and IMPACT studies for triple therapy provided the first evidence for all-cause mortality reduction with a pharmacological intervention in COPD [70, 71], mortality does not currently appear to be considered a driving factor in treatment decisions for patients with COPD outside the specific parameters of long-term oxygen therapy, non-invasive lung ventilation and lung transplantation. Surveys conducted in Europe and the USA showed that prevention of mortality was not among the most common reasons cited by pulmonologists and primary care physicians for choice of prescribed maintenance therapy [91, 92]. The 2023 GOLD report highlighted that triple therapy is the only pharmacotherapy to reduce mortality in COPD [93], and the recently released Canadian Thoracic Society Guidelines went one step further by including mortality reduction in the pharmacological treatment algorithm [94]. However, fundamental change in clinical practice is still needed to ensure prioritisation of cardiopulmonary risk reduction in the management of COPD.

There is a need for the early detection and treatment of COPD in people living with cardiovascular disease and the recognition of COPD as a distinct cardiovascular risk factor. Addressing these needs will support symptom management and reduce future cardiopulmonary events through proactive escalation and optimisation of COPD therapy and management of cardiovascular conditions and risk factors. The development and validation of risk stratification tools may aid improved quantification of COPD-associated cardiopulmonary risk and allow for a more personalised approach to treatment, though such tools are often not employed in routine clinical practice. Responsibility lies with the respiratory community to continue to raise awareness of the burden of respiratory disease and its cardiopulmonary impact and to communicate the urgency for action [24]. Of note, the recent GOLD update for cardiologists sought to encourage greater consideration of COPD within cardiology and promote a multidisciplinary approach to COPD management, increasing partnership between respiratory and cardiology disciplines, as well as with primary care clinicians [89, 95].

Conclusion

In this review, we define cardiopulmonary risk as the risk of serious respiratory and/or cardiovascular events in patients with COPD. These include, but are not limited to, COPD exacerbations, myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure decompensation, arrhythmia and death due to any of these events. We call for the consideration of cardiopulmonary risk in the management of COPD as well as increased efforts for the early identification of patients at high risk. Although further research is necessary to understand the mechanisms of cardiopulmonary risk for improvement of mitigation, evidence supports proactive therapeutic intervention to prevent exacerbations, reduce the risk of cardiopulmonary events and thereby reduce mortality in patients with COPD. Reframing COPD management towards proactive cardiopulmonary risk reduction could transform the standard and management of care and therefore improve clinical outcomes in this population.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Adeloye D, Chua S, Lee C, Basquill C, Papana A, Theodoratou E, et al. Global and regional estimates of COPD prevalence: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2015;5: 020415. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.05.020415.

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease report 2024. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/. Accessed 5 Jan 2024.

World Health Organization. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-(copd). Accessed 6 Feb 2024.

Mathers C. Projections of global deaths from 2016 to 2060 2022. https://colinmathers.com/2022/05/10/projections-of-global-deaths-from-2016-to-2060/. Accessed 9 Nov 2023.

Chen W, Thomas J, Sadatsafavi M, FitzGerald JM. Risk of cardiovascular comorbidity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:631–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00241-6.

Amegadzie JE, Sadatsafavi M. A long overdue recognition: COPD as a distinct predictor of cardiovascular disease risk. Eur Respir J. 2023;62:2301167. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01167-2023.

Müllerova H, Agusti A, Erqou S, Mapel DW. Cardiovascular comorbidity in COPD: systematic literature review. Chest. 2013;144:1163–78. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-2847.

Forfia PR, Vaidya A, Wiegers SE. Pulmonary heart disease: the heart-lung interaction and its impact on patient phenotypes. Pulm Circ. 2013;3:5–19. https://doi.org/10.4103/2045-8932.109910.

Decramer M, Janssens W. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and comorbidities. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:73–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(12)70060-7.

Maclagan LC, Croxford R, Chu A, Sin DD, Udell JA, Lee DS, et al. Quantifying COPD as a risk factor for cardiac disease in a primary prevention cohort. Eur Respir J. 2023;62:2202364. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02364-2022.

Fabbri LM, Celli BR, Agustí A, Criner GJ, Dransfield MT, Divo M, et al. COPD and multimorbidity: recognising and addressing a syndemic occurrence. Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11:1020–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00261-8.

Hurst JR, Skolnik N, Hansen GJ, Anzueto A, Donaldson GC, Dransfield MT, et al. Understanding the impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations on patient health and quality of life. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;73:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2019.12.014.

Hughes R, Rapsomaniki E, Janson C, Keen C, Make BJ, Burgel P-R, et al. Frequent productive cough: symptom burden and future exacerbation risk among patients with asthma and/or COPD in the NOVELTY study. Respir Med. 2022;200: 106921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2022.106921.

Kunisaki KM, Dransfield MT, Anderson JA, Brook RD, Calverley PM, Celli BR, et al. Exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cardiac events. A post hoc cohort analysis from the SUMMIT randomized clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:51–7. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201711-2239OC.

Rothnie KJ, Müllerová H, Smeeth L, Quint JK. Natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations in a general practice-based population with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:464–71. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201710-2029OC.

Mannino DM, Doherty DE, Sonia BA. Global Initiative on Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) classification of lung disease and mortality: findings from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Respir Med. 2006;100:115–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2005.03.035.

Foos V, Mcewan P, Holmgren U, Marshall J, Müllerová H, Nigris ED. Projections of 10-year mortality in patients with COPD in the UK using the CHOPIN policy model. Eur Respir J. 2021;58(Suppl. 65):PA1012. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.congress-2021.PA1012. (Abstract).

Matarese A, Sardu C, Shu J, Santulli G. Why is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease linked to atrial fibrillation? A systematic overview of the underlying mechanisms. Int J Cardiol. 2019;276:149–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.10.075.

Chen C-C, Lin C-H, Hao W-R, Chiu C-C, Fang Y-A, Liu J-C, et al. Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and ventricular arrhythmia: a nationwide population-based cohort study. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2021;31:8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-021-00221-3.

Liu X, Chen Z, Li S, Xu S. Association of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with arrhythmia risks: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8: 732349. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2021.732349.

Finkelstein J, Cha E, Scharf SM. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2009;4:337–49. https://doi.org/10.2147/copd.s6400.

Krishnan S, Tan WC, Farias R, Aaron SD, Benedetti A, Chapman KR, et al. Impaired spirometry and COPD increase the risk of cardiovascular disease: a Canadian cohort study. Chest. 2023;164:637–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2023.02.045.

Carter P, Lagan J, Fortune C, Bhatt DL, Vestbo J, Niven R, et al. Association of cardiovascular disease with respiratory disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2166–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.063.

Amegadzie JE, Gao Z, Quint JK, Russell R, Hurst JR, Lee TY, et al. QRISK3 underestimates the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with COPD. Thorax. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1136/thorax-2023-220615.

Watz H, Tetzlaff K, Magnussen H, Mueller A, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Wouters EF, et al. Spirometric changes during exacerbations of COPD: a post hoc analysis of the WISDOM trial. Respir Res. 2018;19:251. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-018-0944-3.

Suissa S, Dell’Aniello S, Ernst P. Long-term natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: severe exacerbations and mortality. Thorax. 2012;67:957–63. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201518.

Goto T, Shimada YJ, Faridi MK, Camargo CA, Hasegawa K. Incidence of acute cardiovascular event after acute exacerbation of COPD. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1461–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4518-3.

Müllerová H, Marshall J, de Nigris E, Varghese P, Pooley N, Embleton N, et al. Association of COPD exacerbations and acute cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2022;16:17534666221113648. https://doi.org/10.1177/17534666221113647.

Nordon C, Rhodes K, Quint JK, Vogelmeier CF, Simons SO, Hawkins NM, et al. EXAcerbations of COPD and their OutcomeS on CardioVascular diseases (EXACOS-CV) Programme: protocol of multicountry observational cohort studies. BMJ Open. 2023;13: e070022. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-070022.

Graul EL, Nordon C, Rhodes K, Marshall J, Menon S, Kallis C, et al. Temporal risk of non-fatal cardiovascular events post COPD exacerbation: a population-based study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202307-1122OC.

Hawkins NM, Nordon C, Rhodes K, Talukdar M, McMullen S, Ekwaru P, et al. Heightened long-term cardiovascular risks after exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2023-323487.

Vogelmeier C, Simons S, Garbe E, Sin D, Hawkins N, Manito N, et al. Increased risk of severe cardiovascular events following exacerbations of COPD: a multi-database cohort study. Eur Respir J 2023;62:PA3013 (Abstract).

Swart KMA, Baak BN, Lemmens L, Penning-van Beest FJA, Bengtsson C, Lobier M, et al. Risk of cardiovascular events after an exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from the EXACOS-CV cohort study using the PHARMO Data Network in the Netherlands. Respir Res. 2023;24:293. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-023-02601-4.

Dransfield MT, Criner GJ, Halpin, Han MK, Hartley B, Kalhan R, et al. Time‐dependent risk of cardiovascular events following an exacerbation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: post hoc analysis from the IMPACT trial. J Am Heart Assoc 2022;11:e024350. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.121.024350.

Westerik JA, Metting EI, van Boven JF, Tiersma W, Kocks JW, Schermer TR. Associations between chronic comorbidity and exacerbation risk in primary care patients with COPD. Respir Res. 2017;18:31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-017-0512-2.

Curkendall SM, deLuise C, Jones JK, Lanes S, Stang MR, Goehring E, et al. Cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Saskatchewan Canada: cardiovascular disease in COPD patients. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.04.008.

Williams MC, Murchison JT, Edwards LD, Agustí A, Bakke P, Calverley PM, et al. Coronary artery calcification is increased in patients with COPD and associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Thorax. 2014;69:718–23. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-203151.

Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, Locantore N, Müllerova H, Tal-Singer R, et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1128–38. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0909883.

Sadatsafavi M, McCormack J, Petkau J, Lynd LD, Lee TY, Sin DD. Should the number of acute exacerbations in the previous year be used to guide treatments in COPD? Eur Respir J. 2021;57:2002122. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02122-2020.

Ho JK, Safari A, Adibi A, Sin DD, Johnson K, Sadatsafavi M, et al. Generalizability of risk stratification algorithms for exacerbations in COPD. Chest. 2023;163:790–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2022.11.041.

Sharma V, Ali I, van der Veer S, Martin G, Ainsworth J, Augustine T. Adoption of clinical risk prediction tools is limited by a lack of integration with electronic health records. BMJ Health Care Inform. 2021;28: e100253. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjhci-2020-100253.

Dudina A, Lane S, Butler M, Cooney M-T, Graham I. SURF-COPD: the recording of cardiovascular risk in patients with chronic lung disease. QJM. 2018;111:303–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy028.

Müllerová H, Shukla A, Hawkins A, Quint J. Risk factors for acute exacerbations of COPD in a primary care population: a retrospective observational cohort study. BMJ Open. 2014;4: e006171. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006171.

Rapsomaniki E, Müllerová H, Hughes R, Marshall J, Papi A, Reddel H, et al. Frequent productive cough associates with an increased risk of cardiopulmonary outcomes in a real-life cohort of patients with COPD (NOVELTY study). Eur Respir J. 2023;62(Suppl. 67):PA1928 (Abstract).

Van Eeden S, Leipsic J, Paul Man SF, Sin DD. The relationship between lung inflammation and cardiovascular disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:11–6. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201203-0455PP.

Aisanov Z, Khaltaev N. Management of cardiovascular comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12:2791–802. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2020.03.60.

Vassaux C, Torre-Bouscoulet L, Zeineldine S, Cortopassi F, Paz-Díaz H, Celli BR, et al. Effects of hyperinflation on the oxygen pulse as a marker of cardiac performance in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:1275–82. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00151707.

Kent BD, Mitchell PD, McNicholas WT. Hypoxemia in patients with COPD: cause, effects, and disease progression. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2011;6:199–208. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S10611.

Rabe KF, Hurst JR, Suissa S. Cardiovascular disease and COPD: dangerous liaisons? Eur Respir Rev. 2018;27: 180057. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0057-2018.

Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, Burkhart D, Kesten S, Menjoge S, et al. A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1543–54. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0805800.

Vogelmeier C, Hederer B, Glaab T, Schmidt H, Rutten-van Mölken MP, Beeh KM, et al. Tiotropium versus salmeterol for the prevention of exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1093–103. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1008378.

Wedzicha JA, Banerji D, Chapman KR, Vestbo J, Roche N, Ayers RT, et al. Indacaterol–glycopyrronium versus salmeterol–fluticasone for COPD. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2222–34. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1516385.

Lipson DA, Barnhart F, Brealey N, Brooks J, Criner GJ, Day NC, et al. Once-daily single-inhaler triple versus dual therapy in patients with COPD. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1671–80. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1713901.

Rabe KF, Martinez FJ, Ferguson GT, Wang C, Singh D, Wedzicha JA, et al. Triple inhaled therapy at two glucocorticoid doses in moderate-to-very-severe COPD. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:35–48. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1916046.

Halpin DM, Dransfield MT, Han MK, Jones CE, Kilbride S, Lange P, et al. The effect of exacerbation history on outcomes in the IMPACT trial. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:1901921. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01921-2019.

Lipson DA, Barnacle H, Birk R, Brealey N, Locantore N, Lomas DA, et al. FULFIL trial: once-daily triple therapy for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:438–46. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201703-0449OC.

Ferguson GT, Rabe KF, Martinez FJ, Fabbri LM, Wang C, Ichinose M, et al. Triple therapy with budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate with co-suspension delivery technology versus dual therapies in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (KRONOS): a double-blind, parallel-group, multicentre, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6:747–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30327-8.

Vestbo J, Papi A, Corradi M, Blazhko V, Montagna I, Francisco C, et al. Single inhaler extrafine triple therapy versus long-acting muscarinic antagonist therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRINITY): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:1919–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30188-5.

Singh D, Papi A, Corradi M, Pavlišová I, Montagna I, Francisco C, et al. Single inhaler triple therapy versus inhaled corticosteroid plus long-acting β2-agonist therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRILOGY): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:963–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31354-X.

Papi A, Vestbo J, Fabbri L, Corradi M, Prunier H, Cohuet G, et al. Extrafine inhaled triple therapy versus dual bronchodilator therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRIBUTE): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1076–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30206-X.

Bafadhel M, Peterson S, De Blas MA, Calverley PM, Rennard SI, Richter K, et al. Predictors of exacerbation risk and response to budesonide in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a post hoc analysis of three randomised trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6:117–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30006-7.

Pascoe S, Barnes N, Brusselle G, Compton C, Criner GJ, Dransfield MT, et al. Blood eosinophils and treatment response with triple and dual combination therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: analysis of the IMPACT trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7:745–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30190-0.

Bafadhel M, Rabe KF, Martinez FJ, Singh D, Darken P, Jenkins M, et al. Benefits of budesonide/glycopyrronium/formoterol fumarate dihydrate on COPD exacerbations, lung function, symptoms, and quality of life across blood eosinophil ranges: a post hoc analysis of data from ETHOS. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:3061–73. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S374670.

Strange C, Tkacz J, Schinkel J, Lewing B, Agatep B, Swisher S, et al. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2023;18:2245–2256. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S432963

Ismaila AS, Rothnie KJ, Wood RP, Banks VL, Camidge LJ, Czira A, et al. Benefit of prompt initiation of single-inhaler fluticasone furoate, umeclidinium, and vilanterol (FF/UMEC/VI) in patients with COPD in England following an exacerbation: a retrospective cohort study. Respir Res. 2023;24:229. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-023-02523-1.

Löfdahl C-G, Postma DS, Pride NB, Boe J, Thorén A. Possible protection by inhaled budesonide against ischaemic cardiac events in mild COPD. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:1115–9. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00128806.

Hohlfeld JM, Vogel-Claussen J, Biller H, Berliner D, Berschneider K, Tillmann H-C, et al. Effect of lung deflation with indacaterol plus glycopyrronium on ventricular filling in patients with hyperinflation and COPD (CLAIM): a double-blind, randomised, crossover, placebo-controlled, single-centre trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6:368–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30054-7.

Kellerer C, Kahnert K, Trudzinski FC, Lutter J, Berschneider K, Speicher T, et al. COPD maintenance medication is linked to left atrial size: results from the COSYCONET cohort. Respir Med. 2021;185: 106461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106461.

Vestbo J, Anderson JA, Brook RD, Calverley PM, Celli BR, Crim C, et al. Fluticasone furoate and vilanterol and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with heightened cardiovascular risk (SUMMIT): a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1817–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30069-1.

Martinez FJ, Rabe KF, Ferguson GT, Wedzicha JA, Singh D, Wang C, et al. Reduced all-cause mortality in the ETHOS trial of budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol for COPD: a randomized, double-blind, multi-center, parallel-group study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;203:553–64. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202006-2618OC.

Lipson DA, Crim C, Criner GJ, Day NC, Dransfield MT, Halpin DM, et al. Reduction in all-cause mortality with fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol in COPD patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:1508–16. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201911-2207OC.

Vestbo J, Fabbri L, Papi A, Petruzzelli S, Scuri M, Guasconi A, et al. Inhaled corticosteroid containing combinations and mortality in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2018;52:1801230. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01230-2018.

Yang M, Li Y, Jiang Y, Guo S, He J-Q, Sin DD. Combination therapy with long-acting bronchodilators and the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2023;61:2200302. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00302-2022.

Regard L, Burgel P-R, Roche N. Inhaled therapy, cardiovascular risk and benefit–risk considerations in COPD: innocent until proven guilty, or vice versa? Eur Respir J. 2023;61:2202135. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02135-2022.

Stolz D, Cazzola M. Characterising the cardiovascular safety profile of inhaled muscarinic receptor antagonists. In: Martínez-García MÁ, Pépin J-L, Cazzola M, editors. Cardiovascular complications of respiratory disorders. Sheffield: European Respiratory Society; 2020. p. 238–50. https://doi.org/10.1183/2312508X.10028619.

Godtfredsen NS, Lam TH, Hansel TT, Leon ME, Gray N, Dresler C, et al. COPD-related morbidity and mortality after smoking cessation: status of the evidence. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:844–53. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00160007.

Ryrsø CK, Godtfredsen NS, Kofod LM, Lavesen M, Mogensen L, Tobberup R, et al. Lower mortality after early supervised pulmonary rehabilitation following COPD-exacerbations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18:154. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-018-0718-1.

Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial Group. Continuous or nocturnal oxygen therapy in hypoxemic chronic obstructive lung disease: a clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93:391–8. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-93-3-391.

Medical Research Council Working Party. Long term domiciliary oxygen therapy in chronic hypoxic cor pulmonale complicating chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Lancet. 1981;317:681–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(81)91970-X.

Murphy PB, Rehal S, Arbane G, Bourke S, Calverley PM, Crook AM, et al. Effect of home noninvasive ventilation with oxygen therapy vs oxygen therapy alone on hospital readmission or death after an acute COPD exacerbation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317:2177–86. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.4451.

Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, Ferguson GT, Jenkins C, Jones PW, et al. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:775–89.

Pullen R, Miravitlles M, Sharma A, Singh D, Martinez F, Hurst JR, et al. CONQUEST quality standards: for the collaboration on quality improvement initiative for achieving excellence in standards of COPD care. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2021;16:2301–22. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S313498.

Celi A, Latorre M, Paggiaro P, Pistelli R. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: moving from symptom relief to mortality reduction. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2021;12:20406223211014028. https://doi.org/10.1177/20406223211014028.

O’Donnell DE, Webb KA, Neder JA. Lung hyperinflation in COPD: applying physiology to clinical practice. COPD Res Pract. 2015;1:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40749-015-0008-8.

García-Río F. Lung hyperinflation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: clinical and therapeutic relevance. BRN Rev. 2020;6:67–86.

Hwang HJ, Lee SM, Seo JB, Lee JS, Kim N, Kim C, et al. Assessment of changes in regional xenon-ventilation, perfusion, and ventilation-perfusion mismatch using dual-energy computed tomography after pharmacological treatment in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: visual and quantitative analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:2195–203. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S210555.

Singh D, Wild JM, Saralaya D, Lawson R, Marshall H, Goldin J, et al. Effect of indacaterol/glycopyrronium on ventilation and perfusion in COPD: a randomized trial. Respir Res. 2022;23:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-022-01949-3.

Voskrebenzev A, Kaireit TF, Klimeš F, Pöhler GH, Behrendt L, Biller H, et al. PREFUL MRI depicts dual bronchodilator changes in COPD: a retrospective analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2022;4: e210147. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryct.210147.

Shrikrishna D, Taylor CJ, Stonham C, Gale CP. Exacerbating the burden of cardiovascular disease: how can we address cardiopulmonary risk in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Eur Heart J. 2024;45:247–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad669.

Singh D, Holmes S, Adams C, Bafadhel M, Hurst JR. Overcoming therapeutic inertia to reduce the risk of COPD exacerbations: four action points for healthcare professionals. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2021;16:3009–16. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S329316.

Kocks J, Ferreira AJ, Bakke P, van Schayck OC, Ekroos H, Tzanakis N, et al. Investigating the rationale for COPD maintenance therapy prescription across Europe, findings from a multi-country study. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2023;33:18. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-023-00334-x.

Mannino D, Siddall J, Small M, Haq A, Stiegler M, Bogart M. Treatment patterns for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in the United States: results from an observational cross-sectional physician and patient survey. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:749–61. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S340794.

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease report 2023. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/GOLD-2023-ver-1.3-17Feb2023_WMV.pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2024.

Bourbeau J, Bhutani M, Hernandez P, Aaron SD, Beauchesne M-F, Kermelly SB, et al. 2023 Canadian Thoracic Society guideline on pharmacotherapy in patients with stable COPD. Chest. 2023;164:1159–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2023.08.014.

Agusti A, Böhm M, Celli B, Criner GJ, Garcia-Alvarez A, Martinez F, et al. GOLD COPD DOCUMENT 2023: a brief update for practicing cardiologists. Clin Res Cardiol. 2023;2023:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-023-02217-0.

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by Jamie Bradley, PhD, and Nairah Chaudury, MChem, of Helios Medical Communications, Macclesfield, UK, and funded by AstraZeneca.

Funding

This article was funded by AstraZeneca. AstraZeneca provided all necessary scientific bibliography and funded medical writing support and publication charges, including the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access Fee. The authors did not receive direct funding for the writing of this article. Dave Singh is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Manchester Biomedical Research Centre (BRC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dave Singh, MeiLan K. Han, Nathaniel M. Hawkins, John R. Hurst, Janwillem W.H. Kocks, Neil Skolnik, Daiana Stolz, Jad El Khoury, and Chris P. Gale were involved in the following steps and, therefore, qualify for authorship: (1) have made substantial contribution to the concept and design of the article, (2) drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content, (3) approved the version to be published, and (4) agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dave Singh has received consultancy fees from Aerogen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cipla, CSL Behring, EpiEndo, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Glenmark, Gossamer Bio, Kinaset Therapeutics, Menarini, Novartis, Orion, Pulmatrix, Sanofi, Teva, Theravance Biopharma and Verona Pharma. MeiLan K. Han reports personal fees from Aerogen, Altesa BioPharma, Amgen, Apreo Health, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cipla, Chiesi, DevPro, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Integrity, Novartis, Teva, MDBriefCase, Medscape, Medwiz, Merck, Mylan, NACE, Polarian, Pulmonx, Regeneron, Roche, RS BioTherapeutics, Sanofi, UpToDate and Verona Pharma; has received either in-kind research support or funds paid to the institution from the American Lung Association, AstraZeneca, Biodesix, Boehringer Ingelheim, the COPD Foundation, Gala Therapeutics, the National Institutes of Health, Novartis, Nuvaira, Sanofi and Sunovion; has participated in data safety monitoring boards for Medtronic and Novartis with funds paid to the institution; and has received stock options from Altesa BioPharma and Meissa Vaccines. Nathaniel M. Hawkins reports grants, speaker bureau, advisory board and consultancy honoraria from pharmaceutical companies including AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis and Servier. John R. Hurst has received speaker/consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis and Takeda. Janwillem W.H. Kocks reports grants, personal fees and non-financial support from AstraZeneca; grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Boehringer Ingelheim; grants and personal fees from Chiesi; grants, personal fees and non-financial support from GlaxoSmithKline; non-financial support from Mundi Pharma; grants and personal fees from Teva; personal fees from MSD; personal fees from Covis Pharma; personal fees from ALK-Abelló; and grants from Valneva outside the submitted work; holds < 5% shares of Lothar Medtec GmbH and 72.5% of shares in the General Practitioners Research Institute. Neil Skolnik has received speaker/consultancy fees from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Idorsia, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur and Teva; and research funding from AstraZeneca, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi. Daiana Stolz is the current GOLD representative for Switzerland and has received speaker/consultancy fees from Almirall, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, CSL Behring, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Novartis, Sanofi and Vifor; and research grants from AstraZeneca and Curetis. Jad El Khoury is an employee of AstraZeneca and holds shares and stock options in the company. Chris P. Gale has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Medisetter, Menarini, Novartis, Raisio Group, Wondr Medical, Zydus; advisory board and consultancy honoraria from AI Nexus, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cardiomatics, Chiesi, Daiichi Sankyo, General Practitioners Research Institute, iRhythm, Menarini, Novartis, Organon, Phoenix Group; research grants from Abbott Diabetes, Bristol Myers Squibb, the British Heart Foundation, Horizon 2020, and the National Institute for Health and Care Research.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, D., Han, M.K., Hawkins, N.M. et al. Implications of Cardiopulmonary Risk for the Management of COPD: A Narrative Review. Adv Ther 41, 2151–2167 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-024-02855-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-024-02855-4