Abstract

Introduction

Even though increased use of reliever medication, including short-acting beta agonists (SABA), provides an indirect measure of symptom worsening, there have been limited efforts to assess how different patterns of reliever use correlate with symptom control and future risk of exacerbations. Here, we evaluate the effect of individual baseline characteristics on reliever use in patients with moderate-severe asthma on regular maintenance therapy with fluticasone propionate (FP) or combination therapy with fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (FP/SAL) or budesonide/formoterol (BUD/FOR).

Methods

A drug-disease model describing the number of 24-h puffs and overnight occasions was developed with data from five clinical studies (N = 6212). The model was implemented using a nonlinear mixed effects approach and a Poisson function, considering clinical and demographic baseline characteristics. Goodness of fit and model predictive performance were assessed. Heatmaps were created to summarise the effect of concurrent baseline factors on reliever utilisation.

Results

The final model accurately described individual patterns of reliever use, which is significantly increased with time since diagnosis, smoking, higher Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ-5) score and higher body mass index (BMI) at baseline. Whilst the number of puffs decreases slowly after an initial drop relative to the start of treatment, exacerbating patients utilise significantly more reliever than those who do not exacerbate. The mean effect of FP/SAL (median dose: 250/50 μg BID) on reliever use was slightly higher than that of BUD/FOR (median dose: 160/4.5 μg BID), i.e. a 75.3% vs 69.3% reduction in reliever use, respectively.

Conclusions

The availability of individual-level patient data in conjunction with a parametric approach enabled the characterisation of interindividual differences in the patterns of reliever use in patients with moderate-severe asthma. Taken together, individual demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as exacerbation history, can be considered an indicator of the degree of asthma control. High SABA reliever use suggests suboptimal clinical management of patients on maintenance therapy.

Plain Language Summary

In this study, we tried to understand how patients with moderate to severe asthma use their quick-relief inhalers (like albuterol), how it relates to their symptoms and the risk of having asthma attacks. To evaluate whether differences in reliever inhaler use between patients are associated with factors like smoking or their asthma symptoms at the beginning of treatment, we gathered data from five clinical studies (n = 6212 patients). These data allowed us to create a model that predicts how often patients use their reliever inhalers (expressed as number of puffs in 24 h) during maintenance therapy with inhaled corticosteroids alone or in combination with long-acting beta agonists. The final model showed that reliever inhaler use is higher in patients who have been diagnosed with asthma for > 10 years, are smokers, have higher asthma symptom scores, and are obese or extremely obese. Patients who had asthma attacks also used their reliever inhalers more often. In addition, to understand how relief inhalers are used in real-life situations, we also created heatmaps that include a wide range of patient characteristics. By using individual patient data together with this model, we have learned that smoking, asthma control, BMI, long history of asthma and previous asthma attacks significantly influence reliever use. This information can help physicians and healthcare professionals understand know how well someone’s asthma is managed. A patient who uses their reliever inhaler often is likely not to have their asthma well controlled by their regular medications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study |

Historically, reliever medication has aimed at bronchodilation and relief of acute symptoms. It is indicated to mitigate symptom worsening and reduce airway limitation during an asthma attack or prevent it |

Reliever use is therefore in contrast with controller medications, which are aimed at reducing airway inflammation, preventing asthma symptoms and reducing future risk (i.e. exacerbations) |

Previous investigations have shown that many patients misperceive achieving symptom control whilst being reliant on frequent use of reliever medication |

What was learned from this study |

A drug-disease model, based on a Poisson function, can be used to describe and predict interindividual differences in reliever use in patients with moderate-severe asthma |

High heterogeneity in reliever use is associated with different patient/disease baseline characteristics |

Patients with asthma who are current smokers, obese, have a longer history of asthma and show inadequate symptom control (i.e. asthma control questionnaire [ACQ-5] > 1.5) at baseline require more reliever (e.g. short-acting beta agonists [SABA] or short-acting muscarinic antagonists [SAMA]) than those who are non-smokers, have a short history of disease, have BMI < 25 kg/m2 and adequate symptom control (ACQ-5 ≤ 1.5) at baseline |

These factors should be carefully considered during the clinical management of patients with moderate-severe asthma |

Introduction

Asthma affects around 300 million individuals worldwide. It has a heterogenous clinical presentation, including cough, wheeze, dyspnoea, chest tightness or pressure as well as signs of expiratory airflow obstruction [1]. Achievement of asthma control over time, reduced dependency on reliever therapy and a reduction in exacerbation are clear goals of the clinical management of patients with moderate-severe asthma [2, 3]. Previous research has shown that in adults with moderate-severe asthma, exacerbation risk is significantly higher in women, obese subjects, smokers and those who have poor lung function, as assessed by spirometric measures; these factors have also been associated with variable or decreased symptom control [4, 5]. However, despite evidence showing that patients achieving control require less reliever medication and have a lower risk of exacerbation [6], the correlation among symptom control, reliever use and reduction in future risk has not been fully characterised.

To date, it has been shown that improvements in lung function testing are accompanied by symptom reduction and need for reliever use, but less information is available on the correlation with exacerbation risk [7]. In fact, a complex relation appears to exist between controller and reliever medication use and exacerbations [8,9,10,11]. This complexity arises partly because of over-reliance on acute symptom improvement through reliever at the expense of inadequate controller therapy. Real-world data reveal that patients who exhibit low ICS adherence (50% or less) and rely more on reliever use are at higher risk of experiencing exacerbations [12]. Moreover, increased reliever use has been associated with higher incidence of exacerbation, independent of maintenance therapy with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) or ICS/long-acting beta agonist (LABA) combination therapy. Whilst variable adherence to daily ICS or ICS/LABA regimens may stem from the episodic nature of asthma symptoms [13], such findings highlight the importance of ensuring bronchoprotection, irrespective of current symptoms, i.e. adherence to controller medication and maintenance therapy.

From a pharmacological perspective, the complexity in establishing a link among reliever use, symptom control and exacerbation risk may arise from the different time scales, pathways associated with the inflammatory response and airway function. Defining correlations between effects that occur over a different time scale therefore requires longitudinal data, which capture the contribution of patient-related factors and long-term effects of maintenance therapy.

Unfortunately, longitudinal data describing reliever use at individual patient level are scarce, and cross-sectional studies do not overcome this shortcoming. Consequently, there is limited insight into how the interplay among patient-, disease- and treatment-related factors affects the natural history of asthma control [14]. Instead, most reports focus primarily on the history of prior exacerbations, as asthma exacerbations are known to affect airway function and the clinical course of asthma symptoms [15]. However, data collection on reliever use is primarily qualitative or cross sectional [16]. There has been no strictly quantitative approach describing how reliever use influences long-term treatment response in patients on maintenance therapy and which factors determine interindividual variation in reliever use patterns. This represents an important gap in the clinical management of patients, as asthma symptom control and exacerbation risk reduction are directly and indirectly associated with reliever use.

To address this gap, one needs to distinguish short-term fluctuation in airway function, which may be due to a range of triggers resulting in bronchoconstriction, from asthma exacerbations and long-term symptom variation (i.e. individual trajectories), which are likely to reflect the underlying airway inflammation status [17, 18] as well as interindividual differences in demographic and clinical baseline characteristics [3, 19]. The aims of this study were three-fold: (1) to improve individualised patient care by identifying treatable traits and their effects on disease status and reliever use, (2) to quantify the effect of maintenance therapy on reliever use and (3) to understand the interplay between symptom severity and maintenance therapy selection. To this purpose, we analyse daily record data on reliever use in conjunction with a parametric Poisson model to establish the correlation between reliever use and individual patients characteristics, symptom control level and exacerbation in patients with moderate-severe asthma on regular maintenance therapy.

Methods

Data Source

The data used for this analysis were retrieved from the internal GSK clinical data repository, which contains individual patient-level information collected in randomised controlled trials. A flow diagram describing the screening, retrieval and selection process is shown in Fig. S1. Initially, there was a total pool of 17 randomized clinical trials, comprising 24,402 enrolled patients with moderate-severe asthma, with a duration of at least 24 weeks, for which accurate individual patient clinical and demographic baseline details, treatment, dose and dosing regimens were available. Additional selection criteria included studies in which asthma symptom scores were assessed during the course of treatment. These studies were eventually integrated with individual patient data where symptom scores were available only at baseline. Studies in which asthma symptom scores were assessed as ACQ-5 or ACT were prioritised. Finally, the analysis population was only to include patients aged ≥ 18 years with accurate self-reported reliever medication use (frequency, timing of administration) and maintenance therapy records. Studies needed to have accurate details on maintenance therapy and on the occurrence of the first exacerbation event.

Of the initial pool of 17 trials, 5 clinical trials (ADA109055, ADA109057, SAM40027, SAM40040, SAM40056) met all the inclusion criteria. Only these studies had accurate individual patient reliever use records (either overnight occasions or 24-h puffs, measured as whole integers per day) over the course of treatment, along with clinical and demographic baseline details. Reliever consisted of the SABA albuterol/salbutamol 100 µg PRN (as needed). Maintenance therapy consisted in ICS monotherapy or ICS/LABA combination therapy: fluticasone propionate (FP), fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (FP/SAL) or budesonide/formoterol (BUD/FOR). The full data set included 1,753,283 observed days from 6212 subjects who were randomised to receive FP (n = 2077), FP/SAL (n = 3100) or BUD/FOR (n = 1035) over a period of at least 24 weeks up to 1 year. An overview of the clinical study protocols along with treatment details and eventual deviations is shown in Table 1. All studies have been performed according to relevant ethical and clinical guidelines (including the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments) following protocol approval by the designated Ethics Committee/Ethics Review Board. All participants enrolled into the studies have given informed consent, whose terms include the scope of the research presented here.

Analysis Population

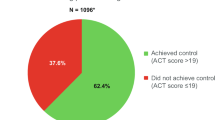

From a total pool of 6744 adult subjects, 6212 had accurate treatment records, baseline asthma symptom control score (ACQ-5 or ACT) and demographic data. The majority were of white ethnicity (n = 4197, 67.6%), while the next highest represented heritage group was “other” (n = 1274, 20.5%). The mean age was 43.9 (range 18.0–91.0) years; 535 patients were ≥ 65 years of age (8.6%). An overview of the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the pooled patient population included in the analysis is summarised per study protocol in Table S1 (Supplementary Material). Histograms describing the distribution of relevant clinical and demographic baseline characteristics were used to assess the heterogeneity and consistency of the patient population across the different studies, which were pooled together for the purpose of the current analysis. A summary of the distributions is shown in Fig. S2 (Supplementary Material).

Given that the individual studies did not record the same baseline variables, individual covariate values were imputed where missing. For continuous covariates, imputed values for an individual patient were based on the median value for the study population while for categorical covariates the most frequent value was used if required. Subsequently, the potential effect of imputation assumptions was evaluated during model building by comparing parameter estimates in the group of patients for whom no covariates were imputed with those obtained for the total population. Table S2 shows the percentage of covariate values that were imputed. The same procedure was applied for missing data in any given study where the variables of interest were collected. Moreover, baseline ACQ-5 was derived from ACT scores for patients included in studies ADA109055 and ADA109057. This was required because only ACT was recorded in these studies and ACQ-5 has been identified as a covariate affecting exacerbation risk and individual symptom trajectories during the course of treatment [5, 20]. Conversion was performed considering the symptom category and percentiles of the scores of each scale. The correlation between scales was calibrated using data from Malinovschi, 2011 [21].

The available data were combined and subsequently divided into a model building and internal validation data set (Fig. 1). The model building data set consisted of studies ADA109055, ADA109057, SAM40027 and SAM40040 (data set 1: N = 5524 patients and n = 1,553,000 records on reliever use). Internal and external validation was aimed at the assessment of model predictive performance. Data set 2 (internal validation) included data from patients with asthma (N = 688) enrolled into study SAM40056, who were treated with either BUD/FOR combination therapy (regular variable doses) or FP/SAL combination therapy (non-variable 50/250 μg BID doses). Individual patient data included in data set 2 were not used during model development.

Diagram describing the number of patients (N) and total number of observations (n) for different data sets used for model building and internal validation. External validation was implemented subsequently with data from a separate study (SAS115359—AUSTRI, NCT01475721) [27], which was not included in the pooled data for this analysis

Count Model Development

The scope of our investigation was to assess the effect of interindividual differences in clinical and demographic baseline characteristics on reliever use. Therefore, study data were pooled together irrespective of the treatment to which patients had been randomised (ICS monotherapy or ICS/LABA combination therapy) [22,23,24]. Initially, an exploratory evaluation was performed to identify patterns in reliever use over time which could be associated with differences in outcome. This exploratory step also served as basis for further assessment of the assumptions underpinning this individual-level model-based meta-analysis (e.g. overdispersion). It also provided insight into potential limitations (e.g. fewer studies in the southern hemisphere) and/or requirements for additional assumptions (e.g. hysteresis) (Table S3).

Further details on the choice of parameterisation are presented in the Supplementary Material. In brief, a Poisson model (also known as a Poisson regression) was used to analyse count data. It describes the observed pattern (mean and variance) of reliever use and allows characterisation of the interindividual differences associated with baseline characteristics and treatment, using a parameterisation of the form:

where θi reflects the extent of change in the predicted number of events for a unit change in covariate Xi.

A different baseline was estimated for each endpoint (θ1 for 24-h puffs and θ2 for overnight occasions).

As several dose levels of FP were available in the studies, a dose-response relationship could be estimated:

where Emax is the maximum possible effect (θ3) and ED50 is the FP dose at which 50% of the maximum effect is reached (θ4). On the other hand, only a single dose level of salmeterol and BUD/FOR was available in the data; thus, this treatment effect was estimated as a categorical variable:

In addition, inspection of the data revealed that after the initial fast drop in reliever use, a slow accrual could be observed over time. This phenomenon was characterised by a hysteresis, which describes the time varying effect:

where Emaxt is the maximum effect that can be achieved (θ7), with ET50 being the time required to reach 50% of the maximum effect (θ8).

Based on the above definitions, the total treatment effect becomes:

The effects of ACQ5, BMI and time since asthma diagnosis (ASTHDUR) were normalised according to the median observed value of each covariate:

Smoking status (current or former) was estimated by estimating a change relative to non-smokers:

In addition, the model included inter-individual variability, which cannot be accounted for any of demographic or clinical explanatory variable, through a normally distributed random variable η with mean 0 and variance Ω.

As overnight occasions and last 24-h puffs were not measured concurrently in any given study, a scaling parameter (θ14) was used to adjust the variance between the two endpoints. In addition, a Box-Cox transform of η was used to account for skewness in the distributions associated with each endpoint:

where θ15 describes the skewness of the distribution (negative for left-leaning, positive for right-leaning).

The combination of all these covariates resulted in the following final model:

Whilst distributions of count data commonly exhibit overdispersion (i.e. where the variance is considerably greater than expected under an assumed distribution) or are zero-inflated (i.e. where excessive zeros beyond what would be expected under a given probability distribution are observed) [25], the Poisson (log-linear) regression proposed here relies on a hierarchical model structure, which allows for the assessment of interindividual variation in the baseline probability [26], disentangling the effect of concurrent covariate factors, such as baseline characteristics from symptom severity and treatment. Inspection of the data revealed no overdispersion or zero inflation; thus, such adjustments were not made to the model.

The predictive performance of the final model was evaluated using standard goodness-of-fit plots and visual predictive checks (VPC), whereas the average relative error and average relative variance (mean square error) were used to assess the precision of parameter estimates and robustness of the model. The analysis was complemented by an external validation step based on a large population of patients with moderate-severe asthma (N = 9715) who were randomised to maintenance therapy with FP or FP/SAL over a period of 26 weeks and for whom reliever medication use was recorded (study SAS115359) [27]. Further details of the evaluation steps are provided in the Supplementary Material. In addition, it should be emphasised that similar methodologies, aimed at characterising interindividual differences in disease processes, disease progression, and treatment response, have been applied elsewhere [5, 28].

Results

Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

Data were pooled from subjects aged 18 to 91 years. Baseline symptom control level (ACQ-5) and airway function (FEV1p) were 1.8 and 75.9%, respectively. Just before the treatment start, 35.9% of patients had an asthma diagnosis > 1 – ≤ 20 years before, and 21.6% had been diagnosed 25 years ago or more. A minor subset (0.8%) of included patients had well-controlled symptom scores (i.e. ACQ-5 < 0.75) at baseline. A more detailed overview of demographic and clinical baseline characteristics per treatment arm can be found in Table 2.

Exploratory Data Analysis

As an initial step, the integrity, accuracy and consistency of the pooled study data were established through exploratory analysis. It should also be noted that reliever use was documented based on self-reported. However, inhalers were provided to the participants and had to be returned at the end of the study. While self-reporting may lead to some inaccuracy, this appeared to be limited in these trials, without further repercussion on model parameter estimates. In fact, data integrity checks did not reveal any unexpected values or deviations for baseline characteristics, treatment allocation or treatment characteristics (Figs. 2, 3). No demographic or clinical baseline characteristics were found to be correlated other than those where this has been previously established, e.g. height and FEV1 (see Figure S3 for details, Supplementary Material).

Exploratory graphs depicting the effect demographic and clinical baseline characteristics on the patterns of overnight reliever use (occasions) in patients with moderate-severe asthma. Variation in the patterns of reliever use at approximately 24 weeks are caused by differences in treatment duration across studies. AQLQ Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire, BMI body mass index, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in the first second, ICS inhaled corticosteroid, PEF peak expiratory flow

Observed reliever use (24-h puffs and overnight occasions) over time in the overall population, stratified by symptom control level at baseline (ACQ-5) (top) and by occurrence of exacerbations (bottom). Mean patterns describe both exacerbating and non-exacerbating patients, with exacerbation defined as in the original study protocols: use of systemic corticosteroids for ≥ 3 days, OR in-patient hospitalization, OR emergency department visit due to asthma requiring systemic corticosteroids. These patterns of reliever use are associated with ICS and ICS/LABA doses according to individual response and/or protocol asthma control plan (FP: 100, 250 and 500 μg twice daily; FP/SAL: 100/50, 250/50 and 500/50 μg twice daily; BUD/FOR: 160/4.5 and 320/9.0 μg twice daily). Legend in each panel indicates the number of patients in each category or group. ACQ-5 Asthma Control Questionnaire, BUD/FOR budesonide- formoterol, FP fluticasone propionate, FP/SAL fluticasone propionate-salmeterol, ICS inhaled corticosteroid, LABA long-acting beta agonist

Count Model Building and Validation

The Poisson model adequately described the individual patterns of reliever use (as overnight occasions as well as 24-h puffs) across the pooled patient population, as well as after stratification by treatment and symptom control level at baseline. Final model components were a basal lambda parameter, covariate coefficients affecting the basal lambda parameter and treatment effects. As estimation of the base lambda describing 24-h puffs showed high variability between subjects and between studies, this parameter was derived separately for studies SAM40027 and SAM40040. Subsequently, it was possible to estimate all parameters with acceptable precision (RSE ≤ 40%, except for the base lambda describing overnight occasions) and without statistically significant correlations between parameters (Table 3). The final model included the following baseline covariates (χ2 < 0.01): BMI, ACQ-5, time since asthma diagnosis (ASTHDUR) and smoking status. These covariates were all found to have a significant effect on the base lambda parameter, independently from the effect of the underlying maintenance therapy.

Notably, smokers on average used 73.5% more reliever compared to a patient that had never smoked. Likewise, reliever use in former smokers was 43.0% higher than in patients who had never smoked. Age and geographical ancestry were not found to significantly affect reliever use. As the pooled data included a wide age range and geographical ancestry, this could be due to the correlation among age, time since asthma diagnosis and other baseline covariates, such as BMI. By contrast, both combination therapies FP/SAL and BUD/FOR were found to produce a significantly higher reduction in reliever use than FP monotherapy. The effect of FP/SAL on reliever use at the dose of 250/50 μg BID was slightly higher than that of BUD/FOR following a dose of 160/4.5 μg BID, i.e. a 75.3% vs 69.3% reduction in reliever use, respectively.

The visual predictive checks in Fig. 4 show that observed reliever use fell within the 95% prediction intervals of those predicted for the same individuals (shaded area) for all studies regardless of endpoint. These results indicate that the final model’s ability to predict reliever use in patients with moderate-severe asthma was acceptable. In addition, model performance was also assessed through a comparison of predicted and observed reliever use after stratification by symptom control at baseline (ACQ 5). However, in two studies (SAM40027 and SAM40040) the average population 24-h puffs was well predicted only for patients who were well controlled and not-well controlled (Fig. S4). On the other hand, individual 24-h puffs were also well predicted for patients who were poorly controlled at baseline. Such a pattern was not observed for overnight occasions, but this deviation was addressed by incorporating individual baseline puffs into the model. Model performance was further demonstrated by internal and external validation procedures using data from studies SAM40056 (Fig. S5) and SAS115359 (Fig. S6, Table S4), respectively.

Visual-predictive check showing predicted overnight occasions (left panel) and 24-h puffs (right panel) over time stratified by treatment and symptom control at baseline. The solid line describes the average observed reliever use over the period of up to 12 months across the overall population. Shaded areas show the 95% prediction interval. “N” is the number of patients contributing to the profiles in each panel. Profiles correspond to the model building population. See figures S5 and S6 for details on the studies used for internal and external validation. ACQ-5 Asthma Control Questionnaire, BUD/FOR budesonide-formoterol, FP fluticasone propionate, FP/SAL fluticasone propionate-salmeterol

Implications of Covariate Effects

A more easily interpretable overview of the effect of baseline covariate factors and treatment on reliever use is presented in Table 4, where starting from the median value of the covariate factor an increase or decrease of 1 unit in the covariate results, respectively, in a percentage increase or reduction in reliever use of the magnitude of the parameter point estimate. As baseline covariates in each single patient consist of a different set of values, heatmaps were created to illustrate the implications of the effect of concurrent covariates on individual patterns of reliever use. For the sake of completeness, heatmaps were created for both endpoints (24-h puffs and overnight occasions), as it is known that asthma symptoms tend to be worse overnight (Figs. 5 and 6). These heatmaps allow us to assess how baseline characteristics can be used as an indicator of individual differences in reliever use in a clinical setting. Of particular interest is the effect of baseline ACQ-5 score, smoking status and BMI, which represent potential treatable traits. In addition, the heatmaps provide insight into how total reliever use varies when considering the differences due to the effect of the underlying maintenance therapy, i.e. the differences between ICS monotherapy and ICS/LABA combination therapy.

Heatmap of predicted 24-h puffs for a varying baseline ACQ-5, smoking status and body mass index (BMI) vs FP dose following monotherapy or combination with SAL; b varying baseline ACQ-5, BMI, smoking status and asthma duration following combination therapy with BUD/FOR or FP/SAL. Changes in the average number of puffs are shown for male and female patients who have never smoked, previously smoked or are current smokers, have a BMI of 20, 25 or 30 kg/m2, and have been diagnosed with asthma recently (< 1 year), 5 or 10 years before the start of treatment. The midpoint for the colour gradient was set to 3.6, which corresponds to the point estimate of the base lambda after FP treatment. The number of 24h puffs was calculated not only taking into account the observed covariate distributions (dotted black lines) in the studies included in the analysis (Figure S2), but also covariate values across a clinically relevant range for the patient population with moderate-severe asthma. This shows the implications of protocol inclusion and exclusion criteria and highlights potential differences in the overall real-life patient population. ACQ-5 Asthma Control Questionnaire, BMI body mass index, BUD/FOR budesonide-formoterol, FP fluticasone propionate, FP/SAL fluticasone propionate-salmeterol

Heatmap of predicted overnight occasions for a varying baseline ACQ-5, smoking status and body mass index (BMI) vs FP dose following monotherapy or combination with SAL; b varying baseline ACQ-5, BMI, smoking status and asthma duration following combination therapy with BUD/FOR or FP/SAL. Changes in the average number of occasions of reliever use overnight are shown for male and female patients who have never smoked, previously smoked or are current smokers, have a BMI of 20, 25 or 30 kg/m2, and have been diagnosed with asthma recently (< 1 year), 5 or 10 years before the start of treatment. The midpoint for the colour gradient was set to 0.58, which corresponds to the point estimate of the base lambda after FP treatment. The number of overnight occasions was calculated not only taking into account the observed covariate distributions (dotted black lines) in the studies included in the analysis (Figure S2), but also covariate values across a clinically relevant range for the patient population with moderate-severe asthma. This shows the implications of protocol inclusion and exclusion criteria and highlights potential differences in the patterns of reliever medication use in the overall real-life patient population. ACQ-5 Asthma Control Questionnaire, BMI body mass index, BUD/FOR budesonide- formoterol, FP fluticasone propionate, FP/SAL fluticasone propionate-salmeterol

From the colour patterns it becomes evident that there is a strong correlation between baseline ACQ-5 and reliever use. In contrast, the contribution of covariates such as BMI and time since asthma diagnosis are relatively limited. Similarly, it is possible to assess the benefit of combination therapy over monotherapy. Such an effect is clearly visible in subjects with a higher baseline ACQ-5. In addition, small but clinically relevant differences can be detected between FP/SAL (250/50 μg BID) and regular dosing BUD/FOR (160/4.5 μg BID) in terms of reliever use reduction.

Discussion

Despite the importance of maintenance therapy, a significant proportion of patients seems to rely on reliever to manage worsening of asthma symptoms. Indeed, a debate has been ongoing on the effect of variable adherence to maintenance therapy and implications of over-reliance on the effects of reliever medication in moderate-severe asthma, in particular short-acting beta-adrenergic agonists (SABA) [29, 30]. Whilst multiple factors may contribute to such a behaviour, there have been limited efforts to assess the interplay among reliever use, symptom control and future risk using longitudinal data. To date, very few studies have evaluated individual patient-level, longitudinal data on reliever use in asthma [31].

Given the known interindividual differences in bronchial reactivity to triggers, the contribution of airway remodelling to airflow limitation and symptoms, and drug and dose-dependent desensitisation of β-2 adrenergic receptors [32], the assessment of individual patterns of reliever use, along with its correlation with the achievement of short/long-term symptom control, and subsequent reduction in exacerbation risk may not be possible without longitudinal data and a model-based approach [33,34,35,36,37]. Here we have attempted to characterise individual patterns of reliever use, mostly short-acting beta adrenergic drugs, in moderate-severe asthma over the course of run-in, titration and maintenance phases of treatment with ICS or ICS/LABA combination therapy.

Mean and individual patterns in reliever use revealed a profile that includes an initial steep drop followed by a slow, gradual decrease in reliever use, which stabilises well after 6 months after initiation of ICS monotherapy or ICS/LABA combination therapy (Figs. 2 and 3). This pattern indicates that inferences about the efficacy of the maintenance dosing regimen based on short term studies may not be accurate. In addition, patients who show poor asthma symptom control at baseline (i.e. ACQ-5 > 1.5) or experience an exacerbation during the course of treatment use significantly more reliever than those who achieve adequate level of control or do not exacerbate. Nevertheless, some reliever medication is still required even by those who achieve symptom control or do not exacerbate (Fig. 7). Such a requirement suggests that airway hyperresponsiveness may not be completely suppressed in the presence of triggers. This may be due to variable adherence to treatment or underuse of ICS, and consequently suboptimal anti-inflammatory response (i.e. bronchoprotection).

Our findings can also indicate that distinct mechanisms or pathways contribute to bronchoconstriction and airway smooth muscle (ASM) homeostasis, as observed in viral exacerbations, during which the ability to respond to bronchodilators is partially or almost completely lost [38, 39]. Loss of homeostasis results in excessive ASM contraction which, in those with poor control, is manifest by variations in airflow resistance over short periods of time [40]. Hence, overlooking the implication of impairment in ASM homeostasis, as well as the time-, drug- and dose-dependent desensitisation of β-2 adrenergic receptors, may lead to confounding and misinterpretation of data on reliever use. In addition, the reversibility of airflow resistance through smooth muscle relaxation and bronchodilation may vary according to the selectivity, potency and actual exposure to β-2 agonists reaching the airways.

Undoubtedly, the identification of asthma duration as a significant baseline covariate suggests progressive desensitisation of beta-adrenergic receptors to beta-adrenergic agonists in patients who have been diagnosed with asthma for > 5 years, leading to higher reliever use. An additional factor might be the progressive development of fixed airflow limitation as a result of airway remodelling. These effects may be further amplified by current smokers, higher BMI and other comorbidities impacting on symptom control. These factors will also vary depending on the maintenance (controller) therapy choice [41, 42].

The final model highlighted the effect of disease history (asthma duration) and interindividual differences in clinical and demographic baseline characteristics on reliever use (i.e. baseline ACQ-5, BMI, smoking status), which directly and indirectly affect airway hyperresponsiveness to environmental and other external triggers. In practice, the effect of baseline covariate factors and maintenance therapy summarised in Table 4 can be interpreted as follows: assuming the average patient requires 3.6 puffs per day at the start of treatment, each increase or decrease of 1 unit in the covariate results, respectively, in a percentage increase or reduction in the number of puffs of overnight occasions of the magnitude of the parameter point estimate (relative to its median value). For instance, for every unit increase in baseline BMI relative to the median (i.e. 26 kg/m2), the number of puffs increases by approximately 2.6% per unit BMI. Hence, a patient with baseline BMI value of 34 kg/m2 (i.e. 8 units higher than the median value) will require 4.3 puffs. That means 0.7 puffs more per 24 h and approximately 22.3% more puffs than a patient with a BMI of 26 kg/m2. Similarly, for every unit increase in ACQ-5, reliever use increases by 75.9%, whereas smoking is associated with 73.5% more reliever use compared to a patient who never smoked.

In contrast to the effect of baseline covariates, the extent of the effect of maintenance therapy is time-, drug- and dose-dependent, with maximum reduction in reliever use being achieved after 12 months from the start of treatment. In fact, the predicted maximum reduction in reliever use is 1.9-fold higher at 12 months than what is observed at the start of treatment. This partly explains the diverging results obtained on reliever use in observational, cross-sectional studies, where time since the onset of maintenance therapy may not be factored into the analysis [8]. Clearly, this time-dependent effect leads to important shortcomings in cross-sectional studies. Hence, whenever exploring overuse of reliever, estimates based on a single figure for the whole population are not adequate and could be misleading.

Reliever use depends not only upon a patient’s baseline characteristics and disease history but also on the duration and choice of drugs used as maintenance therapy. The availability of different FP doses allowed us to quantify the effect of salmeterol (SAL) in the ICS/LABA combination therapy. Whilst the maximum effect of FP was lower than BUD/FOR combination (i.e. a reduction of approximately 69.3%), salmeterol alone appears to contribute significantly to the effect of the combination on reliever use, with an estimated reduction of 38.1%. Furthermore, it was possible to estimate the theoretical median reliever use in the absence of the effect of maintenance controller therapy, which corresponds to 3.6 puffs per 24 h, with an average of 0.6 overnight events. This represents a theoretical consumption of 6.6 canisters per year. Consequently, this estimate provides insight into the magnitude of the effect of ICS/LABA combination therapy on reliever use reduction, which reaches 75.3% following regular dosing with FP/SAL (i.e. from 6.6 to approximately 0.9 canisters per year after the first year of treatment).

Our findings also raise further questions on the conclusions drawn by Bateman and colleagues on the association between higher prescription of short-acting β2-agonists and rates of severe asthma exacerbations [43, 44]. Even though patients exacerbating during the study period appear to use approximately twice as much reliever relative to those who do not exacerbate, such a difference is observed irrespective of treatment type (i.e. monotherapy or combination therapy) and is consistent with previous reports [12]. Hence, it is unlikely that the higher exacerbation rate observed following monotherapy is caused by variable adherence to ICS. Rather, the risk of exacerbation in this group of patients appears to be associated with clinical and demographic covariates [5], suggesting that reliever use is triggered most likely by the inadequate level of bronchoprotection in this population. We hypothesise that this pattern can be explained by distinct mechanisms underpinning the immediate and long-term symptom control in patients who exacerbate and those who do not [39, 45]. Such a distinction is critical, as it becomes evident that inflammation, currently elevated as the underlying cause of the clinical symptoms of asthma, may need to be assessed as another relatively independent component [31, 40, 46].

As schematically summarised in Fig. 7, the increased use of reliever medication in exacerbating patients or in those with a history of moderate and severe asthma exacerbations is not associated with reliever medication itself but with additional treatable traits and external factors [5]. Moreover, the evidence of a dose-dependent effect of ICS and a significantly higher decrease, rather than total suppression in reliever use following ICS/LABA combination therapy with different drugs, suggests that increased bronchial reactivity may involve other pathways than the underlying anti-inflammatory mechanisms by which inhaled corticosteroids act, highlighting that loss of normal homeostatic control of airways smooth muscle (ASM) may play an important role in long-term use of reliever. As to the direct clinical implications of this work, we foresee that evidence of the magnitude of the effect of baseline characteristics, i.e. treatable traits, on reliever use will help clinicians implement personalised interventions and identify opportunities to better manage patients. Obvious recommendations include weight loss, smoking cessation and appropriate selection and earlier initiation of maintenance therapy, considering not only the current disease status (ACQ-5) but also the patient’s disease history (time since asthma diagnosis). The quantification of these effects at individual level will allow the clinician to have a frank conversation as to the expected improvement that lifestyle and treatment choices may have on the patient’s symptoms, exacerbation risk and reliever medication use. It can be anticipated that such choices may also have repercussions on a larger scale, informing education programmes and healthcare services for patients with moderate-severe asthma.

(Upper panel) Diagram describing the effect of patient baseline characteristics (i.e. ACQ-5, body mass index and smoking status), disease history (i.e. asthma duration) and maintenance therapy (i.e. FP, FP/SAL or BUD/FOR) on reliever use and implications for long-term symptom control, risk reduction and potential changes to quality of life. (Lower panel) Mean reliever use over time in the overall study population for whom overnight events were recorded (left) and in patients who show poor symptom control at baseline (ACQ-5 ≥ 1.5) (right), stratified by treatment group and occurrence of exacerbations. Solid and dashed lines represent the observed and model-predicted profiles, respectively. Shaded area depicts the 90% prediction interval. N indicates the number of subjects in each group. ACQ-5 Asthma control questionnaire, BUD/FOR budesonide-formoterol, FP fluticasone propionate, FP/SAL fluticasone propionate-salmeterol

In summary, the implementation of a Poisson model to describe individual patterns of reliever use can be compared to similar research in other therapeutic areas, such as migraine, major depression or epilepsy [32,33,34], where the endpoints of interest are count or frequency data. Hence, we anticipate that our analysis will provide the basis for the evaluation of a range of clinical questions regarding reliever use in asthma and eventually support the implementation of personalised interventions.

We acknowledge that, as with any pharmacometric approach, model predictive performance and generalisability depend highly upon the data available and the clinical questions one aims to address. A few areas have been identified, which could represent a limitation to this investigation, namely, the potential for selection bias due to the limited access to a wider pool of individual patient level data, imputation of missing baseline covariates in some patients for whom information was not recorded, difficulties in discriminating the effect of patient baseline characteristics from maintenance therapy, potential impact of variable adherence and apparent estimates of reliever use rate at the start of maintenance therapy. An overview of the limitations of the clinical trial data and model parameterisation is provided in Table S5 (Supplementary Material).

Conclusions

The availability of individual-level patient data in conjunction with the use of a Poisson model enabled us to distinguish the effect of baseline covariates from that of maintenance therapy and unexplained, random variation. These results also reveal that reliever use is significantly higher in patients with asthma who are current smokers, obese, have a longer history of asthma and show inadequate symptom control (ACQ-5 > 1.5) at baseline than in those who are non-smokers, have a short history of disease, have normal BMI and adequate symptom control (ACQ-5 ≤ 1.5) at baseline. By contrast, reliever use is significantly reduced in patients receiving a regular dosing regimen with ICS/LABA combination therapy than in those receiving ICS monotherapy. Striking differences in reliever use remain over the whole treatment period between patients who exacerbate and those who do not. Whilst it has not been possible to assess whether these differences bear a causal association, the significantly greater reduction in reliever use following ICS/LABA combination therapy reflects the treatment effect on the underlying inflammatory response and airway hyperresponsiveness, relative to ICS monotherapy.

Data Availability

Anonymised individual participant data and study documents can be requested for further research from www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com.

References

Patel VH, Thannir S, Dhanani M, Augustine I, Sandeep SL, Mehadi A, Avanthika C, Jhaveri S. Current limitations and recent advances in the management of asthma. Dis Mon. 2022;69(7): 101483.

Mazurek JM, Syamlal G. Prevalence of asthma, asthma attacks, and emergency department visits for asthma among working adults—national health interview survey, 2011–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(13):377–86.

Blakey JD, Price DB, Pizzichini E, Popov TA, Dimitrov BD, Postma DS, Josephs LK, Kaplan A, Papi A, Kerkhof M, Hillyer EV, Chisholm A, Thomas M. Identifying risk of future asthma attacks using UK medical record data: a respiratory effectiveness group initiative. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(4):1015-1024.e8.

Beasley R, Braithwaite I, Semprini A, Kearns C, Weatherall M, Pavord ID. Optimal asthma control: time for a new target. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(12):1480–7.

Oosterholt S, Pavord ID, Brusselle G, Yorgancıoğlu A, Pitrez PM, Pg A, Teli C, Della PO. Modelling Asthma TrEatment Responses (MASTER): Effect of individual patient characteristics on the risk of exacerbation in moderate or severe asthma: a time-to-event analysis of randomized clinical trials. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2023;89(11):3273–90.

Pfeffer P, Hajmohammadi H, Cole J, Griffiths C, Hull S, De Simoni A. Characteristics of asthma patients overprescribed short-acting beta-agonist (SABA) reliever inhalers stratified by blood eosinophil count in North East London—a cross-sectional observational study. BJGP Open. 2023. https://doi.org/10.3399/BJGPO.2023.0020.

Lugogo NL, DePietro M, Reich M, Merchant R, Chrystyn H, Pleasants R, Granovsky L, Li T, Hill T, Brown RW, Safioti G. A Predictive machine learning tool for asthma exacerbations: results from a 12-week, open-label study using an electronic multi-dose dry powder inhaler with integrated sensors. J Asthma Allergy. 2022;15:1623–37.

Vervloet M, van Dijk L, Weesie YM, Kocks JWH, Dima AL, Korevaar JC. Understanding relationships between asthma medication use and outcomes in a SABINA primary care database study. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2022;32(1):43.

Jiao T, Schnitzer ME, Forget A, Blais L. Identifying asthma patients at high risk of exacerbation in a routine visit: a machine learning model. Respir Med. 2022;198: 106866.

Patel M, Pilcher J, Reddel HK, Qi V, Mackey B, Tranquilino T, Shaw D, Black P, Weatherall M, Beasley R, SMART Study Group. Predictors of severe exacerbations, poor asthma control, and β-agonist overuse for patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(6):751–8.

Patel M, Pilcher J, Reddel HK, Pritchard A, Corin A, Helm C, Tofield C, Shaw D, Black P, Weatherall M, Beasley R, SMART Study Group. Metrics of salbutamol use as predictors of future adverse outcomes in asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013;43(10):1144–51.

Busse W, Stempel D, Aggarwal B, Boucot I, Forth R, Raphiou I, Rabe KF, Reddel HK. Insights from the AUSTRI study on reliever use before and after asthma exacerbations. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(7):1916-1918.e2.

Gibbons DC, Aggarwal B, Fairburn-Beech J, Hinds D, Fletcher M, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Price D. Treatment patterns among non-active users of maintenance asthma medication in the United Kingdom: a retrospective cohort study in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. J Asthma. 2021;58(6):793–804.

Price D, Hancock K, Doan J, Taher SW, Muhwa CJ, Farouk H, Beekman MJHI. Short-acting β2-agonist prescription patterns for asthma management in the SABINA III primary care cohort. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2022;32(1):37.

Gutiérrez FJÁ, Galván MF, Gallardo JFM, Mancera MB, Romero BR, Falcón AR. Predictive factors for moderate or severe exacerbations in asthma patients receiving outpatient care. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17(1):77.

Bateman ED, Price DB, Wang HC, Khattab A, Schonffeldt P, Catanzariti A, van der Valk RJP, Beekman MJHI. Short-acting β2-agonist prescriptions are associated with poor clinical outcomes of asthma: the multi-country, cross-sectional SABINAIII study. Eur Respir J. 2022;59(5):2101402.

Hvidtfeldt M, Sverrild A, Pulga A, Frøssing L, Silberbrandt A, Hostrup M, Thomassen M, Sanden C, Clausson CM, Siddhuraj P, Bornesund D, Nieto-Fontarigo JJ, Uller L, Erjefält J, Porsbjerg C. Airway hyperresponsiveness reflects corticosteroid-sensitive mast cell involvement across asthma phenotypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023; S0091-6749(23)00291-9

Mormile M, Mormile I, Fuschillo S, Rossi FW, Lamagna L, Ambrosino P, de Paulis A, Maniscalco M. Eosinophilic airway diseases: from pathophysiological mechanisms to clinical practice. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(8):7254.

Wadsworth SJ, Sandford AJ. Personalised medicine and asthma diagnostics/management. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2013;13(1):118–29.

Singh D, Oosterholt S, Pavord I, Garcia G, Abhijith PG, Della PO. Understanding the clinical implications of individual patient characteristics and treatment choice on the risk of exacerbation in asthma patients with moderate-severe symptoms. Adv Ther. 2023;40(10):4606–25.

Malinovschi A, Pizzimenti S, Sciascia S, Heffler E, Badiu I, Rolla G. Exhaled breath condensate nitrates, but not nitrites or FENO, relate to asthma control. Respir Med. 2011;105(7):1007–13.

Daley-Yates P, Brealey N, Thomas S, Austin D, Shabbir S, Harrison T, Singh D, Barnes N. Therapeutic index of inhaled corticosteroids in asthma: a dose-response comparison on airway hyperresponsiveness and adrenal axis suppression. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;87(2):483–93.

Daley-Yates PT. Inhaled corticosteroids: potency, dose equivalence and therapeutic index. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(3):372–80.

McDonald VM, Hiles SA, Godbout K, Harvey ES, Marks GB, Hew M, et al. Treatable traits can be identified in a severe asthma registry and predict future exacerbations. Respirology. 2019;24(1):37–47.

Pittman B, Buta E, Krishnan-Sarin S, O’Malley SS, Liss T, Gueorguieva R. Models for analyzing zero-inflated and overdispersed count data: an application to cigarette and marijuana use. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;22(8):1390–8.

Deng C, Plan EL, Karlsson MO. Approaches for modelling within subject variability in pharmacometric count data analysis: dynamic inter-occasion variability and stochastic differential equations. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2016;43(3):305–14.

Stempel DA, Raphiou IH, Kral KM, Yeakey AM, Emmett AH, Prazma CM, Buaron KS, Pascoe SJ, AUSTRI Investigators. Serious asthma events with fluticasone plus salmeterol versus fluticasone alone. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(19):1822–30.

D’Agate S, Chavan C, Manyak M, Palacios-Moreno JM, Oelke M, Michel MC, Roehrborn CG, Della PO. Impact of early vs. delayed initiation of dutasteride/tamsulosin combination therapy on the risk of acute urinary retention or BPH-related surgery in LUTS/BPH patients with moderate-to-severe symptoms at risk of disease progression. World J Urol. 2021;39(7):2635–43.

Williams DM, Rubin BK. Clinical pharmacology of bronchodilator medications. Resp Care. 2018;63(6):641–54.

Amirav I, Garcia G, Le BK, Barria P, Levy G, Aggarwal B, Fahrbach K, Martin A, Phansalkar A, Sriprasart T. SABAs as reliever medications in asthma management: evidence-based science. Adv Ther. 2023;40(7):2927–43.

Scola AM, Chong LK, Chess-Williams R, Peachell PT. Influence of agonist intrinsic activity on the desensitisation of β2-adrenoceptor-mediated responses in mast cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143(1):71–80.

Maas HJ, Danhof M, Della Pasqua OE. Prediction of headache response in migraine treatment. Cephalalgia. 2006;26(4):416–22.

Maas HJ, Snelder N, Danhof M, Della PO. Prediction of attack frequency in migraine treatment. Cephalalgia. 2008;28(8):847–55.

Santen G, Danhof M, Della PO. Evaluation of treatment response in depression studies using a Bayesian parametric cure rate model. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42(14):1189–97.

D’Agate S, Wilson T, Adalig B, Manyak M, Palacios-Moreno JM, Chavan C, Oelke M, Roehrborn C, Della PO. Model-based meta-analysis of individual International Prostate Symptom Score trajectories in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia with moderate or severe symptoms. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;86(8):1585–99.

King MT, Kenny PM, Marks GB. Measures of asthma control and quality of life: longitudinal data provide practical insights into their relative usefulness in different research contexts. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:301–12.

Mandlik DS, Mandlik SK. New perspectives in bronchial asthma: pathological, immunological alterations, biological targets, and pharmacotherapy. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2020;42(6):521–44.

Aggarwal B, Mulgirigama A, Berend N. Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction: prevalence, pathophysiology, patient impact, diagnosis and management. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2018;28(1):31.

Anthracopoulos MB, Everard ML. Asthma: a loss of post-natal homeostatic control of airways smooth muscle with regression toward a pre-natal state. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:95.

Wannenes F, Magni L, Bonini M, Dimauro I, Caporossi D, Moretti C, Bonini S. In vitro effects of β-2 agonists on skeletal muscle differentiation, hypertrophy, and atrophy. World Allergy Organ J. 2012;5(6):66–72.

Santus P, Radovanovic D, Paggiaro P, Papi A, Sanduzzi A, Scichilone N, Braido F. Why use long acting bronchodilators in chronic obstructive lung diseases? An extensive review on formoterol and salmeterol. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26(6):379–84.

Bateman ED, Price DB, Wang H-C, et al. Short-acting β2-agonist prescriptions are associated with poor clinical outcomes of asthma: the multi-country, cross-sectional SABINA III study. Eur Respir J. 2022;59:2101402.

Volpe FM. Cause or consequence? Eur Respir J. 2022;59:2103107.

Bel EH, Timmers MC, Hermans J, Dijkman JH, Sterk PJ. The long-term effects of nedocromil sodium and beclomethasone dipropionate on bronchial responsiveness to methacholine in nonatopic asthmatic subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141:21–8.

Baker JG. The selectivity of beta-adrenoceptor agonists at human β1-, β2- and β3-adrenoceptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160(5):1048–61.

van Dijkman SC. Assessment of lamotrigine exposure-response: differential effects in partial onset versus primary generalised tonic-clonic seizures in adults. In “Personalised pharmacotherapy in paediatric epilepsy : the path to rational drug and dose selection.” PhD thesis, Leiden University, The Netherlands, 2017. (Accessible at: https://scholarlypublications.universiteitleiden.nl/handle/1887/59470?solr_nav%5Bid%5D=e5b9f1cb4dedbc5b88b8&solr_nav%5Bpage%5D=0&solr_nav%5Boffset%5D=0)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Bhumika Aggarwal (GSK, Emerging Markets Regional Medical Director) and Prof. Li Wei (University College London) for their valuable insights, comments and feedback on the methodology, data analysis and interpretation of the results presented in this manuscript.

Funding

GSK sponsored this investigation and paid for the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access Fees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sven van Dijkman and Sean Oosterholt were involved in the analysis and interpretation of study data, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript; Ian Pavord, Guy Brusselle, Arzu Yorgancıoğlu, Paulo Pitrez, Sourabh Fulmali and Anurita Majumdar were involved in the interpretation of study data, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript; Oscar Della Pasqua was involved in the conception/design and interpretation of study data, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Ian Pavord has received honoraria for speaking at sponsored meetings from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Aerocrine, Almirall, Novartis, Teva, Chiesi, Sanofi/Regeneron, Menarini and GSK, and payments for organising educational events from AstraZeneca, GSK, Sanofi/Regeneron and Teva; he has received honoraria for attending advisory panels with Genentech, Sanofi/Regeneron, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Novartis, Teva, Merck, Circassia, Chiesi and Knopp and payments to support FDA approval meetings from GSK; he has received sponsorship to attend international scientific meetings from Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, AstraZeneca, Teva and Chiesi; he has received a grant from Chiesi to support a Phase 2 clinical trial in Oxford; he is co-patent holder of the rights to the Leicester Cough Questionnaire and has received payments for its use in clinical trials from Merck, Bayer and Insmed; and in 2014–2015 he was an expert witness for a patent dispute involving AstraZeneca and Teva; Guy Brusselle has acted as a speaker/consultant for AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Novartis, Sanofi and Teva; Arzu Yorgancıoğlu has received research grants from Novartis, MSD, AstraZeneca and Sanofi, and has acted as a speaker/consultant for AstraZeneca, Abdi İbrahim, GSK, Novartis, Chiesi and Bilim; Paulo Pitrez has acted as a speaker/consultant for AstraZeneca, GSK, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim and Sanofi; Sven van Dijkman, Sean Oosterholt, Sourabh Fulmali, Anurita Majumdar and Oscar Della Pasqua are GSK employees and hold stocks/shares in GSK.

Ethical Approval

The clinical studies included in the present investigation were performed according to ethical and clinical guidelines (including the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments) and approved by the designated Ethics Committee/Ethics Review Board. All participants enrolled into the studies have given informed consent, whose terms include the scope of the research presented here.

Additional information

Oscar Della Pasqua: principal investigator.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van Dijkman, S.C., Yorgancıoğlu, A., Pavord, I. et al. Effect of Individual Patient Characteristics and Treatment Choices on Reliever Medication Use in Moderate-Severe Asthma: A Poisson Analysis of Randomised Clinical Trials. Adv Ther 41, 1201–1225 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-023-02774-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-023-02774-w