Abstract

Introduction

Identifying risk factors for progression to severe COVID-19 requiring urgent medical visits and hospitalizations (UMVs) among patients initially diagnosed in the outpatient setting may help inform patient management. The objective of this study was to estimate the incidence of and risk factors for COVID-19-related UMVs after outpatient COVID-19 diagnosis or positive SARS-CoV-2 test.

Methods

Data for this retrospective cohort study were from the Optum® de-identified COVID-19 Electronic Health Record database from June 1 to December 9, 2020. Adults with first COVID-19 diagnosis or positive SARS-CoV-2 test in outpatient settings were identified. Cumulative incidence function analysis stratified by risk factors was used to estimate the 30-day incidence of COVID-19-related UMVs. Competing risk regression models were used to derive adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for factors associated with UMVs.

Results

Among 206,741 patients [58.8% female, 77.5% non-Hispanic Caucasian, mean (SD) age: 46.7 (17.8) years], the 30-day incidence was 9.4% (95% CI 9.3–9.6) for COVID-19-related emergency room (ER)/urgent care (UC)/hospitalizations and 3.8% (95% CI 3.7–3.9) for COVID-19-related hospitalizations. Likelihood of hospitalization increased with age and body mass index, with age the strongest risk factor (aHR 5.61; 95% CI 4.90–6.32 for patients ≥ 85 years). Increased likelihood of hospitalization was observed for first presentation in the ER/UC vs. non-ER/UC outpatient settings (aHR 2.35; 95% CI 2.22–2.47) and prior all-cause hospitalization (aHR 1.90; 95% CI 1.79–2.00). Clinical risk factors of hospitalizations included pregnancy, uncontrolled diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, and autoimmune disease. A study limitation is that data on COVID-19 severity and symptoms were not captured.

Conclusion

Predictors of COVID-19-related UMVs include older age, obesity, and several comorbidities. These findings may inform patient management and resource allocation following outpatient COVID-19 diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

With expanded testing for COVID-19, most patients are likely to be initially diagnosed in the outpatient setting, but an outpatient diagnosis presents challenges to health care providers for predicting which of these patients will subsequently need additional care |

This study estimated the 30-day incidence of and risk factors for COVID-19-related urgent medical visits after an outpatient COVID-19 diagnosis or positive SARS-CoV-2 test |

What was learned from the study? |

The 30-day incidence of subsequent COVID-19-related emergency room/urgent care/hospitalizations was 9.4%, and 30-day incidence of COVID-19 hospitalization was 3.8%, with older age, higher body mass index, COVID-19 diagnosis in the emergency room or urgent care setting, prior any-cause hospitalization, pregnancy, and uncontrolled diabetes the strongest risk factors for subsequent hospitalization |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14381564.

Introduction

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, with increasing hospitalizations and deaths in the US [1], has led to focused efforts to reduce inpatient mortality, and several therapeutic agents have been found effective [2, 3]. However, with expanded testing, most patients who develop COVID-19 are likely to be initially diagnosed in the outpatient setting. The uncertain natural history of COVID-19 in outpatients presents challenges to health care providers for predicting which patients will subsequently need additional care. Estimating the incidence of COVID-related urgent medical visits (UMVs) to the emergency room (ER), urgent care (UC), or hospital settings and identifying factors associated with these return visits may inform patient management and resource allocation. Such information may be relevant given the initially positive results of trials of monoclonal antibodies for preventing severe COVID-19 among patients first seen in the outpatient setting [4, 5] and the recent granting of Emergency Use Authorization by the US Food and Drug Administration to these two therapies, REGEN-COV2 (a cocktail of casirivimab and imdevimab) and LY-CoV555 (bamlanivimab) [6, 7]. Additionally, publication of a clinical trial of COVID-19 treatment in an outpatient setting [8] suggests the value of characterizing this population for informing design and outcomes of such clinical trials. Therefore, the aims of this study were to characterize US patients initially diagnosed with COVID-19 in the outpatient setting and to estimate the 30-day incidence of and risk factors for subsequent COVID-19-related UMVs using a large, national, electronic health records (EHR) database.

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

Data for this retrospective cohort study were from the Optum® de-identified COVID-19 EHR dataset, which was created to better understand COVID-19 in the real-world setting. The data are sourced from Optum’s longitudinal EHR repository, which encompasses a network of health care provider organizations, mostly integrated delivery networks (IDN), covering > 101 million lives nationally. Information processed across the continuum of care includes data on patient demographics, medications, laboratory results, vital signs, and other observable measurements as well as outpatient and inpatient diagnoses and procedures. The data are certified as de-identified by an independent statistical expert following HIPAA statistical de-identification rules and managed according to Optum® customer data use agreements [9, 10] and currently include approximately 1 million individuals who have either been tested for SARS-CoV-2 or diagnosed with COVID-19 or related conditions since the start of the pandemic; for individual patients, EHR data may extend as far back as January 2007.

We included adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) if they had their first confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis [International Classification of Diseases version 10 (ICD-10) code U07.1] or positive SARS-CoV-2 virus test in the outpatient setting between June 1 and December 9, 2020; the first diagnosis or positive test date was considered the index date. Patients were excluded if they were hospitalized on the index date or had a prior COVID-19/coronavirus diagnosis or a prior positive SARS-CoV-2 virus or antibody test result. Patients diagnosed with COVID-19 before June 1, 2020, were excluded because the early phase of the pandemic may not necessarily reflect current health care, testing, and diagnostic coding practice. Patients were also required to be part of an IDN health system and have ≥ 1 health care encounter within 2 years prior to the index date (baseline period) for assessment of medical history. The authors affirm that this retrospective database analysis did not entail collection, use, or transmittal of identifiable data. Based on 45CFR46.101(b)(4): Existing Data & Specimens—No Identifiers, this study is exempt from the requirement for institutional review board approval. The study is compliant with data security requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996.

Baseline Measures

Location of the initial index COVID-19 outpatient encounter (ER/UC vs. non-ER/UC, including telehealth) and index month were determined. Baseline variables included demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, and geographic region) and the following risk factors for severe COVID-19 based on the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) [11] and the medical literature [12,13,14,15]: cancer, chronic kidney disease (CKD) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cardiovascular disease (CVD), autoimmune disease, obesity, diabetes, sickle cell disease, smoking status (current/former), pregnancy, chronic liver disease, asthma, hypertension, depression, and anxiety. Additionally, the occurrence of ≥ 1 ER/UC visit or hospitalization for any reason during the 2-year baseline period was determined. Except for pregnancy, risk factors were identified using diagnostic and procedure codes during the baseline period that included the index date; pregnancy was identified using diagnostic and procedure codes ≤ 6 months pre-index. Body mass index (BMI) and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels were also identified during the baseline period; if multiple records were present, the one closest to the index date was used. The BMI was categorized as < 18.5, 18–24.9, 25–29.9, 30–34.9, 35–39.9, and ≥ 40 kg/m2. Diabetes was characterized as “controlled” or “uncontrolled” based on HbA1c levels of < 7% and ≥ 7%, respectively.

Outcomes

Outcomes following the initial outpatient COVID-19 diagnosis included (1) the composite endpoint of first COVID-related ER/UC/hospitalization, defined as a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis anywhere on the visit record and (2) the first COVID-19-related hospitalization, defined as a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis as the primary or admitting diagnosis. Patients were followed from the index date until the outcome, death, or end of the study period (December 9, 2020).

Statistical Analysis

Patients were described in terms of demographic and clinical characteristics. Frequency and counts of patients with missing data for a given variable and distribution of the values among patients with complete data for that variable are reported. To account for the competing risk of death, the Cumulative Incidence Function approach was used to estimate the cumulative incidence of COVID-19-related UMVs over the study period overall and stratified by risk factors. Competing risk regression models [16] were used to derive unadjusted hazard ratios with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between individual risk factors and each outcome. Adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) were derived using models that included demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, and geographic region), BMI, comorbidities (diabetes, controlled/uncontrolled diabetes, cancer, CKD, autoimmune disease, COPD, CVD, pregnancy, chronic liver disease, sickle cell disease, hypertension, asthma, depression, and anxiety), smoking status, location of first COVID-19 encounter, baseline period resource use (ER/UC, hospitalization), and index month.

The analytic file was created using Instant Health Data software (Panalgo, Boston, MA, USA). Statistical analyses were conducted, without imputation for missing data, using R version 3.2.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Population Characteristics

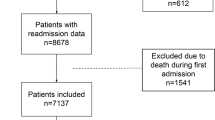

We identified 246,600 patients who had their first COVID-19 diagnosis or positive SARS-CoV-2 test during the study period; among these, 40,129 patients (16.3%) were hospitalized at diagnosis or positive test and were excluded from the analysis (Online Appendix Table 1). Of the remaining 206,741 outpatients who were included, 69.7% had a diagnosis of COVID-19 and tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 on the index date, 25.4% did not have a diagnosis of COVID-19 but tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 on the index date, and 4.9% had a recorded diagnosis of COVID-19 without a record of positive laboratory results for SARS-CoV-2. There were 1550 deaths over a mean follow-up of 71 days.

Patients were primarily female (58.8%), non-Hispanic Caucasian (77.5%), and < 55 years of age (65.2%); the highest geographic representation was from the Midwest (58.7%), and the majority of patients were commercially insured (68.6%; Table 1). The majority of patients (86.6%) were first diagnosed with COVID-19 in the non-ER/UC outpatient setting, and 13.4% were diagnosed in the ER or UC. At least one CDC-defined risk factor for severe COVID-19 was present in 54.8% of patients; obesity was the most frequent (43.5%), and others were hypertension (30.2%), asthma (10.6%), CVD (9.8%), COPD (4.3%), CKD (4.8%), and diabetes (13.0%; Table 1). Among patients with diabetes and HbA1c values available, 37.0% had uncontrolled diabetes (Table 1). Almost half (49.1%) of patients with BMI values available were obese and 12.3% were morbidly obese. During the baseline period, 34.0% of patients had at least one ER/UC visit and 27.4% had at least one hospitalization.

COVID-19-Related ER/UC/Hospitalizations

The 30-day incidence of COVID-19-related ER/UC/hospitalization was 9.4% (95% CI 9.3–9.6) representing 19,520 patients (Fig. 1a); most (90.7%) COVID-19-related ER/UC/hospitalizations occurred within 15 days post-index. Patients first diagnosed with COVID-19 in the ER/UC had a significantly higher rate of subsequent COVID-19-related ER/UC/hospitalization than patients who were diagnosed in non-ER/UC outpatient settings (Table 2).

The 30-day incidence of COVID-19-related ER/UC/hospitalization increased with age and with BMI relative to normal weight; underweight patients also had a higher incidence relative to normal weight (Table 2). Incidence was higher in Hispanic or Black/African American patients; in patients living in the South; and in patients who had either been seen in the ER/UC setting or hospitalized during the baseline period (Table 2). Pregnancy was associated with a 30-day incidence of 15.8% (95% CI 14.7–16.8). Comorbidities that resulted in a higher incidence of ER/UC/hospitalization were CKD (22.8%; 95% CI 21.9–23.6), COPD (21.5%; 95% CI 20.6–22.4), CVD (19.2%; 95% CI 18.7–19.8), and uncontrolled diabetes (18.3%; 95% CI 17.5–19.1; Table 2). Patients with more CDC risk factors had an increasingly higher incidence of ER/UC/hospitalizations that ranged from 9.5% in patients with 1 risk factor (95% CI 9.2–9.7) to 27.0% with ≥ 4 risk factors (95% CI 25.8–28.1; Table 2).

In the adjusted models, the strongest risk factor for ER/UC/hospitalization within 30 days was older age, with aHRs of 2.95 (95% CI 2.76–3.14) and 3.13 (95% CI 2.86–3.39) for those 75–84 years and ≥ 85 years, respectively (Fig. 2). Race and ethnicity were significant risk factors, compared to Whites, with the highest risk among Hispanics followed by Black and Asians (Fig. 2). Other risk factors included COVID-19 diagnosis in the ER/UC setting compared to non-ER/UC outpatient settings (aHR 2.46, 95% CI 2.38–2.54), baseline history of any-cause hospitalization (aHR 2.13; 95% CI 2.06–2.21), pregnancy (aHR 2.07; 95% CI 1.91–2.23), and morbid obesity (aHR 1.71; 95% CI 1.61–1.81). Most individual comorbidities only slightly increased the likelihood of ER/UC/hospitalization (Fig. 2).

Adjusted hazard ratios of risk factors associated with subsequent COVID-19-related ER/UC/hospitalization visit within 30 days following a COVID-19 diagnosis or SARS-CoV-2-positive test in the outpatient setting. BMI body mass index, CI confidence interval, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CVD cardiovascular disease, ER emergency room, UC urgent care

COVID-19-Related Hospitalizations

The incidence of COVID-19-related hospitalizations within 30 days of an outpatient COVID-19 diagnosis or positive SARS-CoV-2 test was 3.8% (95% CI 3.7–3.9), representing 7808 patients (Fig. 1b); most (91.9%) COVID-19-related hospitalizations occurred within 10 days post-index. Patients first diagnosed with COVID-19 in the ER/UC outpatient setting had a significantly higher rate of subsequent COVID-19-related hospitalizations than those diagnosed in non-ER/UC outpatient settings (Table 2).

For all variables except pregnancy, the 30-day incidence of COVID-related hospitalization showed similar trends to those observed for the composite category of ER/UC/hospitalization (Table 2). While pregnancy did not increase the incidence of composite ER/UC/hospitalization in the adjusted model (Fig. 3), pregnancy significantly increased the likelihood of a COVID-19-related hospitalization (aHR 1.47; 95% CI 1.22–0.73). The adjusted models showed that the strongest risk factor for hospitalization within 30 days post-diagnosis was older age, [aHRs 4.91 (95% CI 4.40–5.43) and 5.61 (95% CI 4.90–6.32) for 75–84 years and ≥ 85 years, respectively; Fig. 3]. While non-Hispanic/non-White race and ethnicity were risk factors for hospitalization, Asians had the highest risk of hospitalizations (Fig. 3). Other risk factors were COVID-19 diagnosis in the ER/UC setting (aHR 2.35; 95% CI 2.22–2.47), baseline history of any-cause hospitalization (aHR 1.90; 95% CI 1.79–2.00), and morbid obesity (aHR 2.07; 95% CI 1.88–2.26). The presence of most comorbidities only slightly increased the likelihood of hospitalization (Fig. 3), and, although both uncontrolled and controlled diabetes were associated with a higher likelihood of hospitalization, the aHR was higher with uncontrolled diabetes, 1.46 (95% CI 1.34–1.57) and 1.16 (95% CI 1.07–1.26), respectively (Fig. 3).

Adjusted hazard ratios of risk factors associated with subsequent COVID-19-related hospitalization within 30 days following a COVID-19 diagnosis or SARS-CoV-2 positive test in the outpatient setting. BMI body mass index, CI confidence interval, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CVD cardiovascular disease, ER emergency room, UC urgent care

Discussion

This study, which focused on patients with an initial diagnosis of COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2-positive test in the outpatient setting, found that subsequent COVID-19-related UMVs tended to occur within 10–15 days of the index event; overall 30-day risks of COVID-19-related return visits were 9.4% for ER/UC/hospitalizations and 3.8% for hospitalizations. While multiple demographic variables and comorbidities affected the incidence of subsequent COVID-19-related visits, in adjusted models, the strongest risk factors were older age, setting of first encounter, prior hospitalization, increasing BMI, and pregnancy. Individual comorbidities tended to increase the risk only slightly.

To our knowledge, this is the largest study to evaluate COVID-19 patients diagnosed in the outpatient setting and to estimate the incidence of 30-day UMVs following such a diagnosis. Resource use generally occurred within the first 15 days of the first encounter, which is consistent with the symptomatology and natural history of COVID-19 especially related to the acute phase [17]. Our estimate of 30-day cumulative incidence of 3.8% hospitalization following an outpatient diagnosis or positive SARS-CoV-2 test is considerably lower than the 14.8% reported in a Spanish study of a similar population with regard to sex (58.7% female), age (61.6% < 55 years), and comorbidities [18]. The higher rate may be due to analysis at an earlier time point in the pandemic and use of broader criteria to identify COVID-19 hospitalizations than the current analysis, which relied on a more specific definition of a COVID-19-related hospitalization that consisted of a COVID-19-specific ICD-10 code as the primary or admitting diagnosis. However, it should be noted that our observation of hospitalizations generally occurring within 10 days of diagnosis was consistent with the Spanish study [18].

There were clear positive trends between the 30-day incidence with outcomes of increasing age and BMI. After adjustment, both increased age and BMI remained independent predictors of 30-day COVID-19-related UMVs, with the oldest age groups having the highest aHRs of all the risk factors for both outcomes. Age has consistently been identified as a risk factor for greater disease severity that results in hospitalization and poorer outcomes [19, 20], including among those initially diagnosed with COVID-19 in the outpatient setting [18]. This association is likely a result of greater frailty, including age-related differences in immune response, that may be incompletely captured by comorbidities. Older age may also be a proxy for comorbidities, including dementia, which has recently been shown to be associated with a higher risk of COVID-19 infection and poorer outcomes in the elderly [21]. Similarly, obesity has been reported to convey a higher risk for hospital admission and death [19, 22,23,24] and may be a relevant risk factor among a younger demographic, although the mechanism underlying this relationship remains unclear [22, 25].

Location of first COVID-19 diagnosis or SARS-CoV-2-positive test was an independent predictor of subsequent COVID-19-related ER/UC/hospitalization and COVID-19-related hospitalizations. This observation suggests that patients initially presenting in the ER/UC may have more severe COVID-19 that results in additional health-seeking behavior or medical care than patients whose first encounter is outside of the ER/UC setting. However, it is also possible that at least some of the subsequent resource use may be due to increased vigilance rather than immediate medical need.

While males were slightly more likely to have COVID-19-related UC/ER/hospitalization or hospitalizations within 30-days of an outpatient diagnosis, pregnancy was one of the strongest risk factors for subsequent COVID-19 related visits, although these subsequent visits may be precautionary rather than of necessity. Pregnancy has been identified as a risk factor for severe COVID-19, as pregnant women with COVID-19 were more likely to be hospitalized, admitted to intensive care, and receive mechanical ventilation support than non-pregnant women [26, 27]. Moreover, pregnant women are also potentially at higher risk for adverse birth outcomes such as preterm delivery and pregnancy loss [26, 28]. A more severe manifestation of COVID-19 among pregnant women and increased risk of adverse birth outcomes may explain the strong association between pregnancy and 30-day UMVs.

Race and ethnicity were significant risk factors for both outcomes, albeit the group with the highest risk was different for the composite outcome (Hispanics) than for hospitalizations (Asians). Increased risk and poorer outcomes of COVID-19 have been suggested to disproportionately affect some racial and ethnic minority groups [13, 29, 30]. Such effects may arise from several factors including social and economic determinants as well as a higher prevalence of comorbid conditions in some of these populations and are of special concern because of disparities in health care [31, 32].

While most comorbidities were associated with an increase in 30-day incidence of UMVs, after adjusting for age and other risk factors, the association between most comorbidities and outcomes was weak. Comorbidities that remained independent risk factors for subsequent COVID-19-related UMVs were CKD, autoimmune disease, COPD, CVD, and diabetes. We also found that uncontrolled diabetes conveys a slightly higher risk than controlled diabetes, which is consistent with a study that found that uncontrolled diabetes was associated with poorer outcomes among patients hospitalized for COVID-19 [33]. Interestingly, having a prior baseline hospitalization for any reason was more strongly associated with COVID-19-related health care utilization than individual comorbidities, even after adjusting for other risk factors. A previous hospitalization may be a proxy for frailty, which itself may be a strong risk factor for severe disease and worse outcomes.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include that severity of COVID-19 could not be determined and that neither viral load nor symptom data were reliably captured in the database. We could not determine whether the initial outpatient COVID-19 diagnosis or positive SARS-CoV-2 test was driven by the presence or severity of symptoms. The database is also restricted to patients seeking care within IDNs and may under-represent other populations such as those in rural areas, under-served communities, and those lacking insurance. Misclassification of outcomes is possible; visits occurring outside of IDNs will not be captured and subsequent COVID-19-related visits could be underestimated. Moreover, the reason for the encounter may be prone to error, particularly for UC/ER visits, because COVID-19 may not necessarily have been the primary motivation for seeking care. Furthermore, the database is not nationally representative, with under-representation of some geographic regions, reducing generalizability to the overall US population. Last, this analysis reflects a specific time period that may not necessarily be generalizable based on changes in epidemiology, geographic preparedness, adaptation of measures to reduce risk of infection, and rapidly evolving trends in disease management.

Conclusions

This study characterized patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in the outpatient setting and their subsequent patterns of COVID-19-related UMVs. The overall risk of 30-day COVID-19-related ER/UC/hospitalization was 9.4% and 3.8% for COVID-19-related hospitalizations but they varied substantially by demographic and clinical factors. The strongest risk factors for subsequent COVID-19-related return visits were older age, obesity (with increasing risk with increasing BMI), first presentation in ER/UC, prior hospitalization, and pregnancy. Closer monitoring of these high-risk patients may help reduce subsequent hospitalizations and can be used to guide resource allocation, including identifying outpatients who may benefit from specific therapies.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC COVID Data Tracker. Available from: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases_casesper100klast7days. Accessed 2021 15 January

Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19: preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1813–26.

The Recovery Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1813.

Weinreich DM, Sivapalasingam S, Norton T, et al. REGN-COV2, a neutralizing antibody cocktail, in outpatients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(3):238–51.ACTIV-TICO LY-CoV555 Study Group,

ACTIV-TICO LY-CoV555 Study Group, Lundgren JD, Grund B, et al. A neutralizing monoclonal antibody for hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;384:905–14.

Eli Lilly and Company. Fact Sheet for Health Care Providers Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) of Bamlanivimab 2020. Available from: https://pi.lilly.com/eua/bamlanivimab-eua-factsheet-hcp.pdf. Accessed 2021 10 January

Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. Fact Sheet for Health Care Providers Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) of Casirivimab and Imdevimab 2020. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/143892/download. Accessed 2021 10 January

Lenze EJ, Mattar C, Zorumski CF, et al. Fluvoxamine vs placebo and clinical deterioration in outpatients with symptomatic COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324(22):2292–300.

United States Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS). 45 CFR 164.514(b)(1). Other requirements relating to uses and disclosures of protected health information. Available from: https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?node=pt45.1.164#se45.2.164_1514. Accessed 2021 February 24

United States Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Office of Civil Rights (OCR). Guidance Regarding Methods for De-identification of Protected Health Information in Accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule. November 26, 2012. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/coveredentities/De-identification/hhs_deid_guidance.pdf. Accessed 2021 February 24

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): people with certain medical conditions 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html. Accessed 2020 11 November

Killerby ME, Link-Gelles R, Haight SC, et al. Characteristics associated with hospitalization among patients with COVID-19: metropolitan atlanta, georgia, march-april 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(25):790–4.

Gold JAW, Wong KK, Szablewski CM, et al. Characteristics and clinical outcomes of adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19: Georgia, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(18):545–50.

Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M, et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed Coronavirus disease 2019 - COVID-NET, 14 states, March 1–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):458–64.

Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the lombardy region. Italy JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574–81.

Dignam JJ, Zhang Q, Kocherginsky M. The use and interpretation of competing risks regression models. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(8):2301–8.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Symptoms of coronavirus. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html. Accessed 2020 18 November

Prieto-Alhambra D, Ballo E, Coma E, et al. Filling the gaps in the characterization of the clinical management of COVID-19: 30-day hospital admission and fatality rates in a cohort of 118 150 cases diagnosed in outpatient settings in Spain. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;49(6):1930–9.

Petrilli CM, Jones SA, Yang J, et al. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1966.

Ioannou GN, Locke E, Green P, et al. Risk factors for hospitalization, mechanical ventilation, or death among 10131 US veterans with SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2022310.

Hariyanto TI, Putri C, Arisa J, Situmeang RFV, Kurniawan A. Dementia and outcomes from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2021;93:104299.

Tartof SY, Qian L, Hong V, et al. Obesity and mortality among patients diagnosed with COVID-19: results from an integrated health care organization. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(10):773–81.

Singh S, Bilal M, Pakhchanian H, et al. Impact of obesity on outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in the United States: a multicenter electronic health records network study. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(6):2221–5.

Tamara A, Tahapary DL. Obesity as a predictor for a poor prognosis of COVID-19: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(4):655–9.

Lighter J, Phillips M, Hochman S, et al. Obesity in patients younger than 60 years is a risk factor for COVID-19 hospital admission. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):896–7.

Ellington S, Strid P, Tong VT, et al. Characteristics of women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status - United States, January 22-June 7, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(25):769–75.

Zambrano LD, Ellington S, Strid P, et al. Update: characteristics of symptomatic women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status - United States, January 22-October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(44):1641–7.

Delahoy MJ, Whitaker M, O’Halloran A, et al. Characteristics and maternal and birth outcomes of hospitalized pregnant women with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 - COVID-NET, 13 States, March 1-August 22, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(38):1347–54.

Stokes EK, Zambrano LD, Anderson KN, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 case surveillance - United States, January 22-May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(24):759–65.

Vahidy FS, Nicolas JC, Meeks JR, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: analysis of a COVID-19 observational registry for a diverse US metropolitan population. BMJ Open. 2020;10(8):e039849.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health equity considerations and racial and ethnic minority groups 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html. Accessed 2020 18 November

Newton S, Zollinger B, Freeman J, et al. (2020) Factors associated with clinical severity in Emer- gency Department patients presenting with symp- tomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.08.20246017.

Bode B, Garrett V, Messler J, et al. Glycemic characteristics and clinical outcomes of COVID-19 patients hospitalized in the United States. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2020;14(4):813–21.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was funded by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Regeneron also funded the journal’s Rapid Service Fee.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

The authors thank Ning Wu, PhD, at Regeneron Inc. (Tarrytown, NY) for analytical support, and Audrey Garman, MHS, at Panalgo (Boston, MA) for assistance with data quality control, which was funded by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. Medical writing support in the preparation of this publication was provided by E. Jay Bienen, PhD, an independent medical writer, and funded by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. The authors also thank Prime for formatting and copyediting suggestions for an earlier version of the manuscript.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authors’ Contributions

Dr. Wei had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis. Concept and design: W. Wei, S. Sivapalasingam, S. Mellis, G.P. Geba, J.J. Jalbert. Analysis and interpretation of the data: W. Wei, S. Sivapalasingam, S. Mellis, G.P. Geba, J.J. Jalbert. Drafting of the article: W. Wei, J.J. Jalbert. Critical revision for important intellectual content: W. Wei, S. Sivapalasingam, S. Mellis, G.P. Geba, J.J. Jalbert. Final approval of the article: W. Wei, S. Sivapalasingam, S. Mellis, G.P. Geba, J.J. Jalbert. Provision of study materials or patients: Optum® Statistical expertise: W. Wei. Administrative, technical, or logistic support: W. Wei. Collection and assembly of data: Optum®

Disclosures

Wenhui Wei, Sumathi Sivapalasingam, Scott Mellis, Gregory P. Geba, and Jessica J. Jalbert are employees and shareholders of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The authors affirm that this retrospective database analysis did not entail collection, use, or transmittal of identifiable data. Based on 45CFR46.101(b)(4): Existing Data & Specimens—No Identifiers, this study is exempt from the requirement for institutional review board approval. The study is compliant with data security requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, W., Sivapalasingam, S., Mellis, S. et al. A Retrospective Study of COVID-19-Related Urgent Medical Visits and Hospitalizations After Outpatient COVID-19 Diagnosis in the US. Adv Ther 38, 3185–3202 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01742-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01742-6