Abstract

Introduction

Octreotide acetate subcutaneous injection is indicated to treat acromegaly and the symptoms of carcinoid tumors and vasoactive intestinal peptide tumors (VIPomas). This formative human factors study assessed the octreotide acetate pen injector and accompanying instructions for use (IFU) with self-trained participants.

Methods

The study enrolled patients with diagnoses of acromegaly, carcinoid tumors, or VIPomas and healthcare practitioners (HCPs) who treat patients with these diagnoses. The IFU provided a stepwise process with illustrations to train participants on using the pen injector. Participants familiarized themselves with the pen injector and the IFU before administering 2 unaided injections into skin-like pads; administering the full dose into the pad was considered a successful injection. The investigators evaluated each injection by performance measures—specific tasks necessary to safely and correctly administer the medication—and subjective measures, which included participant comments, feedback from questions, and suggestions for improvements.

Results

The study enrolled 11 participants—8 patients and 3 HCPs. Participants had a success rate of 100% for both injections. Errors included 1 participant priming the pen with the incorrect dose and 2 participants not holding the injector button for 10 s after the injection. Neither error led to a failed injection. To improve the IFU, participants suggested changing the order of wording on the priming step, clarifying illustrations of the plunger, and stronger indications to hold the injector button.

Conclusion

The octreotide pen injector and IFU were usable by self-trained participants. Participant errors and suggestions provided a foundation for recommendations to improve the IFU.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Food and Drug Administration’s guidance for device development recommend human factors testing to identify and mitigate use-related risks for devices. |

What was learned from the study? |

Participants perceived the octreotide acetate pen injector to be easy to use. |

Feedback from the participants of the study led to recommendations to improve the instructions for use. |

Digital features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14339642.

Introduction

Acromegaly, an endocrine disorder stemming from excess production of human growth hormone (hGH), has an annual incidence ranging between 0.2 and 1.1 cases per 100,000 persons, but uncontrolled disease leads to an elevated mortality rate and reduced quality of life [1,2,3,4]. Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), another endocrine disorder, had an incidence of 6.98 per 100,000 persons in 2012, which is increasing [5, 6]. NETs, including vasoactive intestinal peptide tumors (VIPoma) and carcinoid tumors, are frequently not amenable to curative surgery, and symptoms can only be managed [7]. Octreotide acetate is an analog to the natural hormone somatostatin and is prescribed to suppress the effects of hGH and the hormones released by NETs [8, 9].

Historically, patients with acromegaly prefer to have injections administered in a practitioner’s office [10]; however, patients report a preference for self-administration with other injection devices in a variety of conditions [11,12,13]. Additionally, patients, patient advocates, and healthcare practitioners (HCPs) believe patients with NETs are not sufficiently involved in research supporting their treatment [14]. In a series of human factors studies, patients, HCPs, and non-HCP caregivers tested prototype syringes intended to treat acromegaly and NETs, helping to better design a user-centered device [15]. This suggests there is an opportunity to better inform treatment development with greater patient involvement.

Bynfezia™ (octreotide acetate, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc., Princeton, NJ, USA) is a pen injector that delivers a subcutaneous injection of octreotide and was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in January 2020 (NDA 213,224) (Fig. 1) [16, 17]. The octreotide pen injector is indicated to reduce hGH levels in patients with acromegaly, to treat watery diarrhea related to VIPomas, and to treat flushing and diarrhea from carcinoid tumors [17]. To evaluate the clarity of the instructions for use (IFU) and the ease of use of the octreotide acetate pen injector, the investigators conducted a formative human factors study, as recommended by the FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health. A human factors study evaluates a device still in development with the goal of improving user interaction and ensuring safety and efficacy by improving design to minimize potential user errors [18]. Parameters of a human factors study include defining the users and the environment in which the device will be used, delineating tasks for its use in a stepwise fashion, and mediating hazards relating to its use [18]. The IFU is intended to supplement the intuitiveness of a device and reduce risks to the user, providing clear direction on how to accurately and safely deliver medication independently without the oversight of an HCP.

This formative human factors study aimed to evaluate both the device and the IFU. A key objective of the study was to identify weaknesses and risks of both the IFU and the pen injector with the goal of improving the clarity of the IFU and improving the ease of use of the pen injector.

Methods

Ethics Statement

Participants were volunteers who provided informed consent and were compensated for their participation in the study. Study participants retained the right to withdraw consent at any point during the testing. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Risk Analysis and Risk Mitigation

The IFU was written to guide the use of the octreotide pen injector. It contained the stepwise process of using the pen injector along with detailed illustrations to communicate effective administration and safe storage and disposal (Fig. 2). To reduce risks and prevent errors, the IFU warned against specific actions that would lead to misuse. The IFU was developed with the support of a risk analysis, which identified potential risks associated with the use of the octreotide pen injector and ranked them from low to high in terms of harm or injury to a user. The analysis also provided recommendations to mitigate these risks, either through modifications to the device or the IFU.

Tasks with the highest risks included storing the pen, attaching the needle and removing the cover, priming the pen, injecting the dose, and removing the needle. Storing the pen incorrectly carried a high risk because improper storage could lead to drug spoilage, reduced efficacy, or damage to the device. To mitigate this risk, the IFU included a section directing users how to correctly store the pen injector with specific warnings about storage conditions to avoid. The needle must be attached to the pen injector and its cover removed prior to injection and then removed from the pen injector after the injection. These steps carried the risk of needle sticks, delay of injection, or damage to the pen injector. To mitigate the risks surrounding the needle, the IFU contained detailed steps with illustrations and specific instructions for safe handling of the needle. Prior to the first injection, the pen injector must be primed to administer the correct dose. Risks included incorrect dosing if the user did not prime the pen or loss of the drug if the user primed incorrectly or primed the pen again after using the pen to administer a dose. When administering an injection, a user must attach the needle, dial the dose, select an injection site, insert the needle, and deliver the dose. For each step, the IFU detailed the process with illustrations, and the pen injector used a small needle to ensure the needle was easy to insert and delivered a subcutaneous injection.

Study Enrollment

Eligible participants included both patients and HCPs. Participants were required to be adults with a diagnosis and history of a prescription to treat acromegaly, carcinoid tumor, or VIPoma, or an HCP who treated patients with these diagnoses. Participants were excluded if they had uncorrected low vision or blindness or were not proficient in English. Patients employed in the medical field were also excluded.

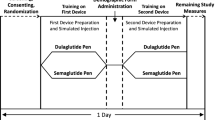

Study Procedure

The study was conducted in the San Francisco Bay area in July 2017. Participants were guided through the study by moderators using a script that featured checkboxes for moderator observations, comments, and potential errors and failure points that drew from the risk analysis. Each participant was assigned to administer injections with doses ranging from 50 to 200 mcg. Patients administered injections to skin-like pads over the thigh and abdomen, and HCPs administered both injections to skin-like pads over the upper arm (Table S1). There was a 5-min break between the first unaided injection and post interaction questions and the administration of the second unaided injection. The moderators recorded subjective and performance measures of each unaided injection, determining whether patients comprehended the IFU sufficiently to successfully deliver a dose using the pen injector (Table 1). Performance measures included identification of specific criteria that defined success of a given task, while subjective measures included comments regarding difficulties with specific tasks and how participants felt about their performance. Knowledge probes and comprehension questions were directed to participants to determine their comprehension of key points necessary for safety and effective administration with the pen injector.

Results

Patient Demographics and Characteristics

Eleven participants enrolled—8 diagnosed with acromegaly, carcinoid tumors, or VIPomas and 3 HCPs. Patients had a mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of 53 (15) years and HCPs had a mean (SD) age of 41 (11) years (Table 2). Of patients previously taking medication to treat their condition, 4 (50%) received medication by infusion, 2 (25%) by prefilled syringe, and 1 (12.5%) by vial and syringe.

Study Outcomes

All participants successfully delivered the full dose of their unaided injections. Using the performance measures, the moderators noted instances of participant mal-interaction with the pen injector; however, these errors did not lead to failure (Table 3). One participant made an error priming the pen injector, using the prescribed dose of 150 mcg instead of the 100 mcg instructed by the IFU. In addition, 2 participants did not hold the injection button for a full 10 s prior to removing the needle from the skin, diverging from the IFU. However, in both instances, the participants delivered the drug in full. During the second injection, participants did not have any mal-interactions with the pen injector.

Using subjective measures, the moderators noted specific comments from participants regarding their perception of success with an injection. Among the patients with mal-interactions, moderators sought feedback on their deviation from the instructions. The participant who primed with 150 mcg instead of 100 mcg felt the injection was appropriately completed, but suggested the IFU should direct users to prime with 100 mcg regardless of the prescribed dose. One participant who did not hold the injector button for a full 10 s remained uncertain if a full dose had been successfully delivered. The participant suggested they missed a step when reading the IFU and advocated for a change to the IFU highlighting the importance of this step. The second participant who did not hold the injection for 10 s felt they successfully completed the injection, noting the dial returned to zero. When the moderator highlighted this error, the participant noted their experience delivering injections and assumed the dial going to zero was sufficient, and suggested a label on the pen to clarify the step. During the second injection, a participant noted they nearly primed the pen a second time, which was a deviation from the IFU. This participant suggested the IFU should highlight that priming should only occur once. After completing both injections, all participants were asked if they would be able to self-administer medication on a regular basis with the pen injector; all 11 participants responded yes.

Participants provided suggestions to improve the clarity of the IFU. One participant expressed confusion about disposing of a used pen injector and 2 commented on the priming step; one cited a confusing illustration indicating when to skip priming, and the other suggested highlighting that priming only occurs during the first use. Two other comments included suggestions to track how long to use the pen injector, proposing the inclusion of a space to write the date marking 28 days of use. One participant did not know how to gauge when the pen injector was almost empty, noting confusion about what the plunger was; they suggested wording changes to the IFU to better define what the plunger looks like and how it indicates when a pen is empty. Two participants recommended adding guidelines to the IFU regarding how long the pen injector should remain outside of the refrigerator to reach room temperature. Participant feedback served as an indicator of gaps in user understanding, and the suggestions provided a foundation for changes or amendments to the IFU.

The investigators used knowledge probes to further assess user comprehension of key components of the IFU. While all 11 participants successfully completed every assessment in the knowledge probe, moderators also noted when the participant referred to the IFU (Table 4). Of note, a majority of participants referred to the IFU to determine where to store the pen (64%) and how to clean the pen (82%). The knowledge probes evidenced participants’ ability to retain and find information in the IFU.

Discussion

The octreotide pen injector performed well with all users. While some participants made errors, none resulted in injection failure. This provides evidence that the risk analysis was valuable in anticipating and mitigating potential risks related to the design of the device and the development of the IFU prior to human factors testing. A clear IFU is an effective tool for patients to reduce their dependence on HCPs for direction and administration. Studies of IFUs suggest that the structure of an IFU, particularly the use of bullet points or lists and pictures, promotes user engagement [19]. Furthermore, IFUs with disorganized contents or small fonts deter potential users from utilizing it [19]. The octreotide pen injector IFU makes use of strategies to encourage its use, providing bullet points for warnings and steps that list summaries of substeps with accompanying illustrations. Additionally, the IFU maintains an organized flow with numbered steps and large text size (Fig. 2). All participants found the accompanying IFU easy to read and useful for self-training to administer an injection with the octreotide pen injector.

The specific task measures to assess participants were informed by the risk analysis. The knowledge probe findings suggest participants had not completely internalized the instructions, as many participants referred to the IFU to verify their response. However, all participants were able to complete the knowledge probe successfully and demonstrated they could retrieve the information from the IFU if necessary. Additionally, the mal-interactions signified points where future users might make mistakes, potentially reducing the safety and efficacy of the pen injector. Points of misunderstanding or confusion highlighted by the task measures and knowledge probes led to recommended changes in the IFU and device for further refinement.

In response to the participant comment that the IFU did not provide explicit instructions regarding disposal of damaged, expired, or empty pen injectors, the investigators suggested adding step-by-step directions on how to dispose of the pen injector in household trash or a sharps container. It was unclear to 1 participant how to determine when the pen injector was nearly empty, leading to a suggested update to the illustration in the check medication step, and adding to the wording to better communicate how the appearance of the plunger indicates when to use a new pen injector. Participants noted that the IFU did not explicitly state how long to let the pen injector sit to reach room temperature prior to injection. To address this, investigators recommended the addition of instructions to clarify how long to leave the pen out within a specific temperature range. Regarding the priming step, investigators proposed amending a confusing stepwise process for the user, changing the wording to improve the logical flow of the IFU. Multiple subjects consulted the IFU to help determine potential injection sites, and investigators concluded the wording about selecting injection sites could be confusing. Investigators proposed clarifying potential injection sites by simplifying the wording to ensure users did not use the same injection site for consecutive injections. To directly address the error made by 2 participants in which they removed the needle from the injection site prematurely, investigators suggested adding simple, single-word callouts to the illustrations to correct any misunderstandings regarding holding the injector button and to ensure users received the full dose of the drug.

All patients agreed that the IFU was easy to follow, supported by a 100% injection success rate. The octreotide pen injector has the potential to expand accessibility and give patients control over their own treatment; 50% of patients in this study previously received their treatment as an infusion. In another study, a majority of patients with NETs willing to try self- or partner injection indicated a preference for it, citing greater independence and practicality [12]. Furthermore, self- or partner injections reduced costs per patient injection compared to injections administered by an HCP, suggesting self-administration could reduce financial burden and healthcare resource utilization [12]. Among patients with diabetes and multiple sclerosis, similar pen injector devices are associated with better treatment adherence and improved quality of life [20, 21]. In studies comparing different methods of drug delivery, users showed a preference for subcutaneous pen injectors over intravenous drug delivery or prefilled syringes [11, 22]. Users frequently reported ease of use and reduced pain with pen injectors designed to deliver medication for a variety of diagnoses [11, 22, 23]. Furthermore, in a comparison of different methods of insulin delivery, pen injectors were significantly more accurate than syringes at low doses, and comparable in accuracy to implanted pumps [24]. Pen injectors can deliver medication accurately and easily and give patients direct control over their treatment and well-being.

The FDA recently approved a new oral form of octreotide (Mycapssa®, Chiasma, Inc., Needham, MA) for long-term treatment in patients with acromegaly who have responded to and tolerated previous octreotide or lanreotide treatment [25]. This new treatment gives patients with acromegaly who are already taking octreotide a new option for better control over their health [26]. However, before patients are able to switch to the oral form of octreotide, they must respond to and tolerate treatment with octreotide in an injectable form. The pen injector evaluated in our study delivers medication accurately and easily, making this an ideal treatment for patients with acromegaly, VIPomas, and NETs.

Limitations

This study had a small sample size of 11 participants; as such, the findings may not fully elucidate all the potential errors that users can make. A larger scale study may reveal previously unidentified weaknesses in either the pen injector design or IFU. Furthermore, this study did not include non-HCP caregivers. Non-HCP caregivers may be responsible for treating patients with physical limitations such as blindness or for treating non-English-speaking patients. As such, non-HCP caregivers should be included in subsequent studies to ensure all potential users can use the octreotide pen injector and accompanying IFU effectively and safely.

Conclusions

Patients diagnosed with acromegaly, carcinoid tumors, and VIPomas and HCPs with experience treating patients with these conditions were successful at delivering 2 injections with the octreotide pen injector after self-training on the IFU. This formative human factors study paves the way for summative studies with an expanded test group using a device and IFU with improvements recommended by investigators. These improvements will make for safer and easier use of the octreotide acetate pen injector among self-trained users. Additionally, these findings support the use of the octreotide acetate pen injector to accurately and easily deliver medication for patients from the convenience of home, providing them with direct control over their treatment.

References

Lavrentaki A, Paluzzi A, Wass JA, Karavitaki N. Epidemiology of acromegaly: review of population studies. Pituitary. 2017;20:4–9.

Bolfi F, Neves AF, Boguszewski CL, Nunes-Nogueira VS. Mortality in acromegaly decreased in the last decade: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018;179:59–71.

Fleseriu M, Biller BMK, Freda PU, et al. A pituitary society update to acromegaly management guidelines. Pituitary. 2021;24:1–13.

Melmed S. Pituitary-tumor endocrinopathies. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:937–50.

Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, et al. Trends in the incidence, prevalence, and survival outcomes in patients with neuroendocrine tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1335–42.

Hallet J, Law CHL, Cukier M, Saskin R, Liu N, Singh S. Exploring the rising incidence of neuroendocrine tumors: a population-based analysis of epidemiology, metastatic presentation, and outcomes. Cancer. 2015;121:589–97.

Stueven AK, Kayser A, Wetz C, et al. Somatostatin analogues in the treatment of neuroendocrine tumors: past, present and future. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3049.

Rai U, Thrimawithana TR, Valery C, Young SA. Therapeutic uses of somatostatin and its analogues: current view and potential applications. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;152:98–110.

Vance ML, Harris AG. Long-term treatment of 189 acromegalic patients with the somatostatin analog octreotide. Results of the International Multicenter Acromegaly Study Group. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1573–8.

Follin C, Karlsson S. Attitudes and preferences in patients with acromegaly on long-term treatment with somatostatin analogues. Endocr Connect. 2016;5:167–73.

Dashiell-Aje E, Harding G, Pascoe K, DeVries J, Berry P, Ramachandran S. Patient evaluation of satisfaction and outcomes with an autoinjector for self-administration of subcutaneous belimumab in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Patient. 2018;11:119–29.

Johanson V, Wilson B, Abrahamsson A, et al. Randomized crossover study in patients with neuroendocrine tumors to assess patient preference for lanreotide Autogel((R)) given by either self/partner or a health care professional. Patient Prefer Adher. 2012;6:703–10.

Schulze-Koops H, Giacomelli R, Samborski W, et al. Factors influencing the patient evaluation of injection experience with the SmartJect autoinjector in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33:201–8.

Leyden S, Kolarova T, Bouvier C, et al. Unmet needs in the international neuroendocrine tumor (NET) community: assessment of major gaps from the perspective of patients, patient advocates and NET health care professionals. Int J Cancer. 2020;146:1316–23.

Adelman DT, Van Genechten D, Megret CM, Truong Thanh XT, Hand P, Martin WA. Co-creation of a lanreotide autogel/depot syringe for the treatment of acromegaly and neuroendocrine tumours through collaborative human factor studies. Adv Ther. 2019;36:3409–23.

US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Bynfezia Pen NDA 213224 approval letter, January 28, 2020. Retrieved Nov 7 2020, from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=213224.

Bynfezia Pen™ (octreotide acetate) injection. Full Prescribing Information. Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc., Cranbury, NJ, USA.

Food and Administration D. Applying human factors and usability engineering to medical devices. Silver Spring, MA: US Food and Drug Administration (2016).

Cherne N, Moses R, Piperato SM, Cheung C. How medical device instructions for use engage users. Biomed Instr Technol. 2020;54:258–68.

Pozzilli C, Schweikert B, Ecari U, Oentrich W. BetaPlus Study g. Supportive strategies to improve adherence to IFN beta-1b in multiple sclerosis—results of the betaPlus observational cohort study. J Neurol Sci. 2011;307:120–6.

Lee IT, Liu HC, Liau YJ, Lee WJ, Huang CN, Sheu WH. Improvement in health-related quality of life, independent of fasting glucose concentration, via insulin pen device in diabetic patients. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15:699–703.

Kivitz A, Cohen S, Dowd JE, et al. Clinical assessment of pain, tolerability, and preference of an autoinjection pen versus a prefilled syringe for patient self-administration of the fully human, monoclonal antibody adalimumab: the TOUCH trial. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1619–29.

Molife C, Lee LJ, Shi L, Sawhney M, Lenox SM. Assessment of patient-reported outcomes of insulin pen devices versus conventional vial and syringe. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2009;11:529–38.

Keith K, Nicholson D, Rogers D. Accuracy and precision of low-dose insulin administration using syringes, pen injectors, and a pump. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2004;43:69–74.

Mycapssa(R) (octreotide ) delayed release capsules. Full Prescribing Information. Chiasma, Inc., Scotland, UK.

Samson SL, Nachtigall LB, Fleseriu M, et al. Maintenance of acromegaly control in patients switching from injectable somatostatin receptor ligands to oral octreotide. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;1:105.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was funded by Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd. The Rapid Service Fee and Open Access Fee were funded by Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Ian Perry, PhD, of AlphaBioCom, LLC (King of Prussia, PA), and funded by Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content; approved the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Prior Presentation

Data from this manuscript was presented at ENDO 2021, San Diego, California, March 20–23, 2021.

Disclosures

Anthony Andre is the owner of Interface Analysis Associates, which was contracted to perform the study for Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd. Nicholas Squittieri is an employee of Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc. Satyashodhan B Patil is an employee of Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

We thank the participants of the study. Participants were volunteers who provided informed consent and were compensated for their participation in the study. Study participants retained the right to withdraw consent at any point during the testing. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Andre, A., Squittieri, N. & Patil, S.B. Evaluation of the Octreotide Acetate Pen Injector and its Instructions for Use in a Formative Human Factors Study. Adv Ther 38, 3129–3142 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01739-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01739-1