Abstract

Background

Few studies have evaluated the clinical burden of concomitant joint disease in patients with psoriasis (PSO). The objective of this study was to assess comorbidity rates in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) compared with PSO alone.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of US patients with prevalent PSO. Linked medical claims and electronic health records (EHR) in Optum’s de-identified Integrated Claims-Clinical dataset were analyzed from 2007 to 2018. Patients were followed for up to 5 years after the first claim/diagnostic code for PSO (index date). Baseline comorbidity prevalence and follow-up rates (cases per 1000 person-years) were assessed using descriptive statistics. Comorbidity rate analysis included patients with the respective comorbidity at baseline.

Results

Baseline demographics and comorbidity prevalence were numerically similar between patients with concomitant joint disease (PSO-PsA) and those with PSO alone (PSO-only). During follow-up, comorbidity rates were higher in patients in the PSO-PsA group than patients in the PSO-only group. Ratios of PSO-PsA comorbidity rates relative to PSO-only ranged from 1.1 for allergies and infections to 1.7 for fatigue, diabetes, and obesity. Comorbidity rate ratios increased from year 1 to year 5 for hypertension (1.05–1.34), hyperlipidemia (0.94–1.13), diabetes (1.00–1.49), cardiovascular disease (1.03–1.66), depression (0.97–1.19), and anxiety (0.87–0.98).

Conclusions

Patients with PsA have a larger clinical burden, characterized by higher comorbidity rates, than those with PSO. Future research should explore PsA risk factors and how physicians can monitor and treat patients with PSO to reduce the risk of PsA and the associated clinical burden.

Plain Language Summary

Psoriasis is a disease that causes scaly, red skin patches that are itchy or painful. About one-third of people who have psoriasis also develop joint pain. This combination of skin symptoms and joint disease is known as psoriatic arthritis. Having psoriatic arthritis can have a greater effect on people’s quality of life than having psoriasis alone. People with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis often have other medical conditions that are not related to their skin or joints. We know that some conditions, such as obesity and high blood pressure, are more common in people with psoriatic arthritis than in those who only have psoriasis. However, more evidence is needed to understand if this pattern is also seen with other medical conditions. We used a large database of medical insurance claims and electronic health records to see what other medical conditions people with psoriatic arthritis or psoriasis had. We found that people with psoriatic arthritis were more likely to have other medical conditions than those with only psoriasis, including high blood pressure, obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and mental health conditions. These differences became larger over the years covered by this study (2007–2018). The results of this study show that people with psoriatic arthritis are more likely to have additional medical conditions than those who have psoriasis alone. Therefore, it is very important that doctors understand how to reduce the risk of joint disease in their patients with psoriasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

About 30% of patients with psoriasis progress to psoriatic arthritis, an inflammatory disease that causes inflammation and swelling of the joints in addition to skin symptoms. |

However, few studies have evaluated the clinical burden of concomitant joint disease in patients with psoriasis. |

The objective of this study was to assess comorbidity rates in patients with psoriatic arthritis compared with psoriasis alone. |

What was learned from the study? |

These results show that patients with psoriatic arthritis have higher rates of other diseases beyond the skin and joints, such as metabolic syndrome and depression, than those with psoriasis alone. |

These findings highlight the need for future studies to determine how physicians can improve monitoring of psoriasis to reduce the risk of psoriatic arthritis and the associated clinical burden. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide and plain language summary, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14153735.

Introduction

Psoriasis (PSO) is a chronic immune disorder that affects 3% of the adult US population [1] and causes scaly, red skin patches and itching or burning sensations [2]. Many patients with PSO are diagnosed with comorbidities, including obesity, metabolic syndrome, anxiety, depression, infections, and chronic pulmonary disease [3,4,5,6]. Approximately 30% of patients with PSO progress to psoriatic arthritis (PsA) [7], an inflammatory disease that causes inflammation and swelling of the joints and entheses in addition to skin symptoms [8].

PsA is burdensome for both patients and the healthcare system [9, 10], but few studies have compared the relative clinical burden in patients who develop PsA to those without concomitant joint disease. Patients in the USA with PsA have higher annual healthcare costs than those with PSO alone owing to utilization of more inpatient and outpatient services, emergency room visits, and drug prescriptions [11]. Patients with PsA also have reduced quality of life and increased functional disability compared to those with PSO alone [12].

Rates of comorbid disease may be higher in patients with PsA than in patients with PSO alone because of the increased systemic inflammatory burden of concurrent skin and joint disease [13,14,15]. Indeed, as shown in analyses of medical claims and electronic medical records databases, patients with PsA have a higher risk of developing comorbid metabolic conditions and obesity compared with patients who have PSO alone [16,17,18]. However, a comprehensive analysis of comorbidities in US patients with PsA compared to patients with PSO is lacking. The primary objective of this study was to assess the clinical burden of concomitant joint disease by retrospectively comparing comorbidity rates of US patients with PsA or PSO based on medical claims and electronic health records (EHR).

Methods

Study Design

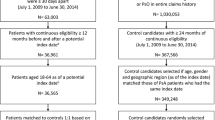

This was a retrospective claims and EHR-based analysis of commercially insured patients with prevalent PSO and no prior evidence of PsA in the USA from January 1, 2007 to March 31, 2018. This study used Optum’s de-identified Integrated Claims-Clinical dataset. The date of the first recorded claim or code for PSO during this analysis was the index date, although this was not necessarily a new PSO diagnosis. Patients were followed for up to 5 years, and there was no minimum follow-up period (Fig. 1). Outcomes were compared between patients with a claim or diagnostic code for PsA after the index date (PSO-PsA) and those without a claim or diagnostic code for PsA after the index date (PSO only). As this database consists of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) compliant de-identified data, no ethics committee approval was required.

Study design. aThere was no minimum follow-up period. bOverall comorbidity rates (cases/1000 person-years) were recorded during follow-up until earliest occurrence of PsA diagnosis, disenrollment from the health plan, death, or after 5 years. PsA was confirmed by claims-based diagnosis, EHR-based diagnosis, or provider note for psoriatic arthritis/arthropathy. cRates of comorbidities (events/person-year), recorded in claims or EHR, were reported during follow-up until earliest occurrence of end of data, disenrollment, death, or 5 years. EHR electronic health records, PsA psoriatic arthritis, PSO psoriasis

Participants

Patients were selected on the basis of medical claims and/or EHR data between January 1, 2008 and March 31, 2018 to allow for at least 1 year of records before the index date. Eligible participants were aged between 18 and 65 years at the index date and had continuous medical and pharmacy benefits, without gaps in enrollment, during the 1-year baseline period before the index date. Patients older than 65 years of age were excluded in order to examine patients close to the age of PSO onset, which typically occurs before age 60 [19].

This study was designed to enroll patients with prevalent PSO. Patients with PSO were identified using International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnostic codes (696, 696.1) or ICD-10-CM codes (L40, L40.0, L40.1, L40.2, L40.3, L40.4, L40.8, L40.9) on inpatient or outpatient medical claims or EHR data. Patients were required to have two medical claims for PSO that were 30–365 days apart. Patients were excluded if they had medical claims or EHR encounters for PsA, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, osteoarthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis in the year prior to the index date. Patients were also excluded if they did not come from a source that supplied physician notes.

PsA diagnosis after the index date was confirmed by ICD-9-CM (696.0) or ICD-10-CM (L40.52, L40.53, L40.54, L40.51, L40.59) codes in medical claims or EHR data or a provider note for “psoriatic arthritis” or “psoriatic arthropathy.”

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics, including age, gender, alcohol use, and smoking, were assessed at baseline (before the index date). Baseline comorbidity prevalence before PSO diagnosis was also evaluated. Comorbidity prevalence is represented as the number and percentage of patients in the PSO-PsA or PSO-only groups with each comorbidity. An overall 365-day Charlson–Deyo comorbidity score [20] was calculated for patients at baseline.

Analysis of Comorbidity Rates

The primary objective of this study was to retrospectively compare comorbidity rates in patients in the PSO-PsA and PSO-only groups. Comorbidities were identified in medical claims or EHR data with the corresponding ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM diagnostic codes (Table S1 in the supplementary material). Baseline prevalence and rates of the following comorbidities during follow-up, which are common in patients with PSO, were evaluated: diabetes (type 1 or 2), cardiovascular disease, hypertension, chronic pulmonary disease, hyperlipidemia, obesity, depression, anxiety, fatigue, infections, and allergies [3,4,5,6, 9, 10]. Baseline comorbidity prevalence was defined in each group as the number of patients with each disease divided by the total number of patients. Comorbidities during follow-up were identified once, at first occurrence of a related claim or diagnosis code in the EHR. Patients with a comorbidity at baseline were not excluded from the analysis of that comorbidity during follow-up. Patients were censored from the analysis of a comorbidity after the first claim or diagnostic code in EHR for that comorbidity.

Separate analyses were performed to compare rates of new cases of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease in patients without metabolic syndrome at baseline in the PSO-PsA and PSO-only groups. Rates of new cases of depression as well as anxiety were also evaluated in patients without depression at baseline.

Overall comorbidity rates during follow-up were recorded in all patients until the earliest occurrence of PsA diagnosis, disenrollment from the health plan, death, or up to 5 years/1825 days. Assessment of overall comorbidity rates was limited to the period before the first claim, diagnostic code, or provider note for PsA. In the PSO-PsA group, only claims or diagnostic codes for comorbidities that occurred prior to the first record of a PsA diagnosis were counted in the comorbidity rate analysis.

Rates of claims or encounters with codes for comorbid conditions were also assessed during follow-up by counting the number of occurrences per person-year. Again, patients were followed up until the earliest occurrence of end of data, disenrollment, death, or 5 years/1825 days, regardless of when the first record of PsA occurred for the patients in the PSO-PsA group. Crude ratios of rates of claims or encounters with codes for comorbidities in patients in the PSO-PsA group compared with patients in the PSO-only group were reported for each year of follow-up.

Data were loaded into the Aetion Evidence Platform® (AEP) [21] and cross-checked against the original data. All analyses were performed in the AEP.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate baseline characteristics (demographics, lifestyle characteristics, and comorbidity prevalence) as well as comorbidity rates during follow-up. Mean and standard deviation (SD) are provided for continuous variables. Comorbidity rates during follow-up are expressed as cases per 1000 person-years and are represented in bar charts showing means and 95% confidence intervals. Crude ratios of rates of claims or encounters with relevant codes (events per person-year) are shown in bar charts. The amount of missing data for each variable is reported where applicable. No imputations for missing data were performed.

Results

Patient Baseline Characteristics

The final study population comprised 19,333 patients with prevalent PSO. Of these, 2311 (12.0%) had a claim, diagnostic code, or provider note for PsA during follow-up, while the remaining 17,022 (88.0%) did not have a record of PsA during follow-up (Fig. 2).

Baseline patient characteristics, including age, gender, and lifestyle, were numerically similar between the PSO-PsA and PSO-only groups. Gender information was unknown or missing for 14 (0.6%) patients in the PSO-PsA group and 93 (0.5%) patients in the PSO-only group. There were no other missing data.

Proportions of patients with comorbid diseases were numerically similar at baseline between the PSO-PsA and PSO-only groups. The most common comorbidities occurring in at least 25% of patients in both populations were hypertension (PSO-PsA 29.6% vs PSO-only 27.8%) and hyperlipidemia (26.2% vs 25.8%). Charlson–Deyo comorbidity scores were also similar at baseline (PSO-PsA 0.59 vs PSO-only 0.55; Table 1).

Duration of Follow-Up

The median follow-up time until occurrence of PsA in the PSO-PsA group was 332.0 days (interquartile range [IQR] 111.0, 742.0). In the PSO-only group, the median follow-up time was 815.0 days (IQR 403.8, 1445.0).

Overall Comorbidity Rates During Follow-Up

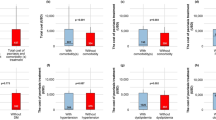

Comorbidity rates were higher in the PSO-PsA group compared with the PSO-only group, including rates of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, fatigue, diabetes, chronic pulmonary disease, obesity, cardiovascular disease, depression, and anxiety (Fig. 3). Crude ratios of comorbidity rates in the PSO-PsA group during follow-up compared with the PSO-only group ranged from 1.1 for allergies and infections to 1.7 for fatigue, diabetes, and obesity (Fig. 3).

Overall comorbidity rates during follow-up. Patients were followed up for 5 years or until earliest occurrence of PsA, disenrollment from the study, or death. Comorbidities were defined as the occurrence of medical services or EHR diagnoses based on ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM codes. Overall comorbidity rates during the follow-up period are shown. Repeat events within patients were not counted. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Crude ratios of comorbidity rates in patients in the PSO-PsA group relative to the PSO-only group are indicated above the bars. aStreptococcus, earache, bronchitis, tonsillitis, or respiratory infection. EHR electronic health record; ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM International Classification of Disease, 9th/10th Revision, Clinical Modification; PsA psoriatic arthritis, PSO psoriasis

In the subset of patients who did not have metabolic syndrome or anxiety/depression at baseline, the rates of these conditions were higher in the PSO-PsA group than the PSO-only group during follow-up. The rates of new hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease cases were 1.3–2.1 times higher in the PSO-PsA group than the PSO-only group (Fig. 4a). Similarly, the rate of new cases of depression was 1.5 times higher in patients in the PSO-PsA group who did not have depression at baseline (Fig. 4b).

Overall comorbidity rates during follow-up in patients without metabolic syndrome or depression during baseline. Patients were followed up for 5 years or until earliest occurrence of PsA, disenrollment from the study, or death. Comorbidities were defined as the occurrence of medical services or EHR diagnoses based on ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM codes. Overall comorbidity rates during the follow-up period are shown in a patients without metabolic syndrome at baseline and b patients without depression at baseline. Repeat events within patients were not counted. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Crude ratios of comorbidity rates in patients in the PSO-PsA group relative to PSO-only are indicated above the bars. aNo baseline hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, or cardiovascular disease. EHR electronic health record; ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM International Classification of Disease, 9th/10th Revision, Clinical Modification; PsA psoriatic arthritis, PSO psoriasis

Yearly Rates of Comorbidities

Crude ratios of rates of comorbid diseases in patients in the PSO-PsA group relative to PSO-only increased from year 1 to year 5 of follow-up, including hypertension (1.05–1.34), hyperlipidemia (0.94–1.13), diabetes (1.00–1.49), cardiovascular disease (1.03–1.66), depression (0.97–1.19), and anxiety (0.87–0.98) (Fig. 5). Rates of all comorbidity events stratified by year of follow-up can be found in Table S2 in the supplementary material.

Ratios of metabolic syndrome and depression/anxiety rates in patients with vs without PsA during follow-up. Follow-up ended on earliest occurrence of end of data, disenrollment, death or end of 5-year follow-up period. Values are reported by annual time interval during follow-up. Ratios of rates of claims (events/person-year) for metabolic syndrome, depression, and anxiety in patients in the PSO-PsA group during follow-up compared with patients in the PSO-only group are shown. Comorbidity events were defined as the occurrence of medical services or EHR diagnoses based on ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM codes. All events were counted for each comorbidity, including repeat events within patients. EHR electronic health record, ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM International Classification of Disease, 9th/10th Revision, Clinical Modification; PsA psoriatic arthritis, PSO psoriasis

Discussion

This retrospective study analyzed the linked medical claims and EHR data of 19,333 US patients with prevalent PSO to compare comorbidity rates between patients who did and did not have concomitant joint disease during follow-up. The results show that during follow-up, patients in the PSO-PsA group had higher rates of comorbidities than patients without concomitant joint disease, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, fatigue, diabetes, chronic pulmonary disease, obesity, cardiovascular disease, depression, and anxiety.

Of the 19,333 enrolled patients with prevalent PSO, 12.0% of patients had either a claim, diagnostic code in EHR data, or provider note for PsA during the follow-up period. This incidence of PsA claims is higher than previously published estimates of cumulative arthritis incidence 5 years (1.7%) and 20 years (5.1%) after PSO onset based on medical records [22]. However, as patients’ entire medical histories were not examined, it was not possible to confirm whether patients in the PSO-PsA group were newly diagnosed in the current study.

In the present study, comorbidity rates in the PSO-PsA group were higher than in the PSO-only group. Notably, rates of metabolic syndrome and depression were higher in the PSO-PsA group than in the PSO-only group, even when excluding patients who had these diseases at baseline. These findings are consistent with four previous analyses of medical claims or electronic medical records in the USA as well as the UK [16,17,18]. A 2017 study using MarketScan data to assess US patients reported greater incidence of hypertension (incidence rate ratio [IRR] = 1.2), diabetes (IRR = 1.1), hyperlipidemia (IRR = 1.1), and obesity (IRR = 1.3) in patients with PsA than in those with PSO [18]. Similarly, a 2017 Truven Health MarketScan analysis reported that patients with PsA had higher prevalence of anxiety, depression, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia than those with PSO alone [11]. Finally, two UK studies of electronic medical records reported that patients with PsA had higher incidence rates of comorbidities than those with PSO alone, including diabetes (1.1–1.5 times higher in PsA than in PSO) [16, 17] and hypertension (1.5 times higher in PsA than in PSO) [17]. As all of these studies measured incident comorbidity cases during follow-up, patients with each comorbidity at baseline were likely excluded from the analyses of each respective comorbidity during follow-up [16,17,18]. The current study, however, did not exclude patients with comorbidities at baseline. Therefore, our results are not directly comparable with those from the previous studies, with the exception of the additional analyses of metabolic syndrome and depression rates in patients without these conditions at baseline.

Compared with the previous studies, the current analysis generally found higher crude ratios of rates of new hypertension (1.5), hyperlipidemia (1.3), and diabetes (2.1) cases in the PSO-PsA group relative to the PSO-only group. This discrepancy may be explained by the exclusive use of claims or electronic records in the previous studies. The Optum integrated database used in the current study comprised claims and EHR data and, therefore, provided a more complete and accurate picture of comorbidity rates than either claims or electronic health/medical records alone [23]. In addition to database analyses, an observational study in Toronto, Canada also reported higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome and depression/anxiety in patients with PsA compared to patients with PSO [24]. The current study, however, took a novel approach, using both medical claims and linked EHR data to compare a wide range of comorbidities in patients in the PSO-PsA and PSO-only groups.

The systemic inflammatory burden of concurrent skin and joint disease may contribute to higher comorbidity rates in the PSO-PsA group than in the PSO-only group. Although we excluded patients with a PsA diagnosis during the 1-year baseline period, it is likely that the systemic inflammatory burden and the associated comorbidities were already increasing prior to the first recorded formal diagnosis [25]. Both PsA and PSO alone are associated with elevated levels of circulating pro-inflammatory markers [26, 27]. Patients with PsA, however, have higher levels of molecular and cellular inflammatory markers than those with PSO alone, including blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios and C-reactive protein [13,14,15]. This heightened systemic inflammation in PsA compared with PSO may lead to higher rates of metabolic syndrome [28, 29], chronic pulmonary disease [30, 31], and mental health conditions [32]. Interestingly, fatigue is also a predictor of PsA in patients with PSO [33]. The tendency of fatigue to precede joint symptoms may also explain the high rates of fatigue in the PSO-PsA population during follow-up. Furthermore, biologics that inhibit the pro-inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α may improve metabolic markers, such as waist circumference, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, insulin, and body mass index (BMI) [34, 35], as well as cardiovascular disease, depression, and fatigue in patients with PSO [36,37,38,39]. These studies may support a link between systemic inflammation and the development of comorbidities, although more evidence is needed.

The increase in comorbidity rates, particularly metabolic syndrome and depression, in the PSO-PsA group relative to PSO-only from year 1 to year 5 of follow-up may reflect a growing divergence in systemic inflammation in these populations over time. It is indeed likely that patients were already developing joint inflammation and symptoms prior to the first recorded diagnosis, as PsA diagnosis is often delayed [25]. However, these results were based on a simple crude analysis. Future studies should investigate whether addressing the underlying inflammation in patients with concurrent joint disease can prevent comorbidities that may result from elevated inflammation.

Obesity may also link PSO to the development of joint symptoms and other comorbidities. Obesity and higher BMI have been associated with increased risk of PSO [40, 41] and PsA [42, 43] as well as metabolic syndrome [44,45,46,47,48] and depression [49]. PSO may further exacerbate the risk of obesity and resulting comorbidities [50]. The increased rate of obesity in the PSO-PsA group compared with the PSO-only group described herein is consistent with previous observational and claims-based studies [18, 24], and may contribute to higher rates of other comorbidities.

The risk factors that contribute to the development of PsA in patients with PSO are complex and poorly understood [51]. Given the increased comorbidity rates in patients with PsA, it will be important for future studies to determine how to best monitor and treat patients with PSO in an attempt to delay or reduce the risk of concomitant joint disease and the associated clinical burden.

This study is subject to limitations inherent to retrospective claims and EHR-based studies. Information from EHR may not have reflected uniform standards of patient assessment and care within and between centers. In addition, EHR facilities may have differed in how thoroughly they reported information such as medical history. The accuracy of diagnosis codes could also not be verified, and information about the severity of PSO was not available. The positive predictive value of ICD-9 codes in detecting PsA using electronic medical records has been estimated at 64% [52]. However, we also analyzed provider notes, which have been shown to substantially improve PsA identification in EHR analyses compared with codes alone [53]. Additionally, patients with claims for rheumatoid arthritis or gout were not excluded, and patients with PsA who were misdiagnosed with these conditions may have been missed. This analysis also did not control for potential confounders that may have influenced comorbidity rates during follow-up, such as baseline comorbidity prevalence. Finally, the unequal sample sizes, due to a smaller number of patients developing PsA than not, may have skewed mean comorbidity rates. Therefore, averages must be examined in the context of the size of the cohort and the SD values. In addition, future studies should assess PSO-PsA and PSO-only comorbidity rates in comparison to rates of these conditions in the general population. Data on prescribed treatments should also be considered to validate diagnostic codes and to control for therapies that may have exacerbated comorbidities [54].

Although the interpretation of this study is subject to limitations, the medical claims database provided access to a large number of patients across many facilities and allowed for a relatively long follow-up period. Although this study only included insured patients, which limits the generalizability of the results to uninsured US patients and those covered by Medicare or Medicaid, the size and diversity of the cohort support the reported findings.

Conclusions

We have shown that patients with PSO and concomitant joint disease have a larger clinical burden, characterized by higher comorbidity rates, than those with PSO alone. These findings highlight the need for future studies to explore the risk factors for PsA and how to best monitor and treat patients with PSO to delay or reduce the risk of joint disease.

References

Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(3):512–6.

Langley R, Krueger G, Griffiths C. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheumatic Dis. 2005;64(suppl 2):ii18–23.

Feldman SR, Hur P, Zhao Y, et al. Incidence rates of comorbidities among patients with psoriasis in the United States. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24(10):13030/qt2m18n6vj.

Abuabara K, Azfar RS, Shin DB, Neimann AL, Troxel AB, Gelfand JM. Cause-specific mortality in patients with severe psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in the UK. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(3):586–92.

Ungprasert P, Srivali N, Thongprayoon C. Association between psoriasis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dermatol Treat. 2016;27(4):316–21.

Dowlatshahi EA, Wakkee M, Arends LR, Nijsten T. The prevalence and odds of depressive symptoms and clinical depression in psoriasis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(6):1542–51.

Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Papp KA, et al. Prevalence of rheumatologist-diagnosed psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis in European/North American dermatology clinics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(5):729–35.

Bagel J, Schwartzman S. Enthesitis and dactylitis in psoriatic disease: a guide for dermatologists. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19(6):839–52.

Feldman SR, Zhao Y, Shi L, Tran MH, Lu J. Economic and comorbidity burden among moderate-to-severe psoriasis patients with comorbid psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2015;67(5):708–17.

Kaine J, Song X, Kim G, Hur P, Palmer JB. Higher incidence rates of comorbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis compared with the general population using US administrative claims data. J Manage Care Special Pharm. 2019;25(1):122–32.

Al Sawah S, Foster SA, Goldblum OM, et al. Healthcare costs in psoriasis and psoriasis sub-groups over time following psoriasis diagnosis. J Med Econ. 2017;20(9):982–90.

Rosen CF, Mussani F, Chandran V, Eder L, Thavaneswaran A, Gladman DD. Patients with psoriatic arthritis have worse quality of life than those with psoriasis alone. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(3):571–6.

Chandran V, Cook RJ, Edwin J, et al. Soluble biomarkers differentiate patients with psoriatic arthritis from those with psoriasis without arthritis. Rheumatology. 2010;49(7):1399–405.

Kim DS, Shin D, Lee MS, et al. Assessments of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and platelet to lymphocyte ratio in Korean patients with psoriasis vulgaris and psoriatic arthritis. J Dermatol. 2016;43(3):305–10.

Strober B, Teller C, Yamauchi P, et al. Effects of etanercept on C-reactive protein levels in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(2):322–30.

Dubreuil M, Rho YH, Man A, et al. Diabetes incidence in psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis: a UK population-based cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53(2):346–52.

Edson-Heredia E, Zhu B, Lefevre C, et al. Prevalence and incidence rates of cardiovascular, autoimmune, and other diseases in patients with psoriatic or psoriatic arthritis: a retrospective study using Clinical Practice Research Datalink. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(5):955–63.

Radner H, Lesperance T, Accortt NA, Solomon DH. Incidence and prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, or psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2017;69(10):1510–8.

Henseler T, Christophers E. Psoriasis of early and late onset: characterization of two types of psoriasis vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13(3):450–6.

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–9.

Aetion Evidence Platform®. Software for real-world data analysis. New Yok: Aetion; 2020.

Wilson FC, Icen M, Crowson CS, McEvoy MT, Gabriel SE, Kremers HM. Incidence and clinical predictors of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(2):233–9.

Wilson J, Bock A. The benefit of using both claims data and electronic medical record data in health care analysis. Eden Prairie: Optum; 2012.

Husted JA, Thavaneswaran A, Chandran V, et al. Cardiovascular and other comorbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis: a comparison with patients with psoriasis. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(12):1729–35.

Karmacharya P, Wright K, Achenbach SJ, et al. Diagnostic delay in psoriatic arthritis: a population based study. J Rheumatol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.201199.

Dowlatshahi EA, van der Voort EA, Arends LR, Nijsten T. Markers of systemic inflammation in psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(2):266–82.

Sokolova MV, Simon D, Nas K, et al. A set of serum markers detecting systemic inflammation in psoriatic skin, entheseal, and joint disease in the absence of C-reactive protein and its link to clinical disease manifestations. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020;22(1):26.

Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Sharrett AR, et al. Markers of inflammation and prediction of diabetes mellitus in adults (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study): a cohort study. Lancet. 1999;353(9165):1649–52.

Han TS, Sattar N, Williams K, Gonzalez-Villalpando C, Lean ME, Haffner SM. Prospective study of C-reactive protein in relation to the development of diabetes and metabolic syndrome in the Mexico City Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(11):2016–21.

Dahl M, Vestbo J, Lange P, Bojesen SE, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. C-reactive protein as a predictor of prognosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(3):250–5.

Groenewegen KH, Postma DS, Hop WC, et al. Increased systemic inflammation is a risk factor for COPD exacerbations. Chest. 2008;133(2):350–7.

Pasco JA, Nicholson GC, Williams LJ, et al. Association of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein with de novo major depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;197(5):372–7.

Eder L, Polachek A, Rosen CF, Chandran V, Cook R, Gladman DD. The development of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis is preceded by a period of nonspecific musculoskeletal symptoms: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(3):622–9.

Costa L, Caso F, Atteno M, et al. Impact of 24-month treatment with etanercept, adalimumab, or methotrexate on metabolic syndrome components in a cohort of 210 psoriatic arthritis patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33(6):833–9.

Marra M, Campanati A, Testa R, et al. Effect of etanercept on insulin sensitivity in nine patients with psoriasis. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2007;20(4):731–6.

Tyring S, Gottlieb A, Papp K, et al. Etanercept and clinical outcomes, fatigue, and depression in psoriasis: double-blind placebo-controlled randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2006;367(9504):29–35.

Fleming P, Roubille C, Richer V, et al. Effect of biologics on depressive symptoms in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(6):1063–70.

Strober B, Gooderham M, de Jong E, et al. Depressive symptoms, depression, and the effect of biologic therapy among patients in Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(1):70–80.

Pina T, Corrales A, Lopez-Mejias R, et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy improves endothelial function and arterial stiffness in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: a 6-month prospective study. J Dermatol. 2016;43(11):1267–72.

Setty AR, Curhan G, Choi HK. Obesity, waist circumference, weight change, and the risk of psoriasis in women: Nurses’ Health Study II. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(15):1670–5.

Kumar S, Han J, Li T, Qureshi AA. Obesity, waist circumference, weight change and the risk of psoriasis in US women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(10):1293–8.

Klingberg E, Bilberg A, Bjorkman S, et al. Weight loss improves disease activity in patients with psoriatic arthritis and obesity: an interventional study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21(1):17.

Love TJ, Zhu Y, Zhang Y, et al. Obesity and the risk of psoriatic arthritis: a population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(8):1273–7.

Narayan KV, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Gregg EW, Williamson DF. Effect of BMI on lifetime risk for diabetes in the US. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1562–6.

Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, et al. Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(11):790–7.

Van Gaal LF, Mertens IL, Christophe E. Mechanisms linking obesity with cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2006;444(7121):875–80.

Landsberg L, Aronne LJ, Beilin LJ, et al. Obesity-related hypertension: pathogenesis, cardiovascular risk, and treatment: a position paper of the Obesity Society and the American Society of Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens. 2013;15(1):14–33.

Jung UJ, Choi M-S. Obesity and its metabolic complications: the role of adipokines and the relationship between obesity, inflammation, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(4):6184–223.

Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):220–9.

Herron MD, Hinckley M, Hoffman MS, et al. Impact of obesity and smoking on psoriasis presentation and management. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(12):1527–34.

Scher JU, Ogdie A, Merola JF, Ritchlin C. Preventing psoriatic arthritis: focusing on patients with psoriasis at increased risk of transition. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2019;15(3):153–66.

Asgari MM, Wu JJ, Gelfand JM, et al. Validity of diagnostic codes and prevalence of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in a managed care population, 1996–2009. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(8):842–9.

Love TJ, Cai T, Karlson EW. Validation of psoriatic arthritis diagnoses in electronic medical records using natural language processing. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;40(5):413–20.

Gisondi P, Cotena C, Tessari G, Girolomoni G. Anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha therapy increases body weight in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis: a retrospective cohort study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(3):341–4.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study and the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access Fees were sponsored by UCB Pharma. Support for third-party writing assistance for this article provided by Jenna Hebert, PhD, Costello Medical, Boston, MA, USA and Sarah Jayne Clements, PhD, Costello Medical, Cambridge, UK was funded by UCB in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

Medical Writing, Editorial and Other Assistance

The authors thank the investigators and their teams who took part in this study. The authors also acknowledge Mylene Serna, PharmD, UCB Pharma, Smyrna, GA, USA for publication coordination and Jenna Hebert, PhD, from Costello Medical, Boston, MA, USA and Sarah Jayne Clements, PhD, from Costello Medical, Cambridge, UK, for medical writing and editorial assistance based on the authors’ input and direction. This study was funded by UCB Pharma.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

Substantial contributions to study conception/design, or acquisition/analysis/interpretation of data: Michelle Skornicki, Patricia Prince, Robert Suruki, Edward Lee and Anthony Louder; Drafting of the publication, or revising it critically for important intellectual content: Michelle Skornicki, Patricia Prince, Robert Suruki, Edward Lee and Anthony Louder; Final approval of the publication: Michelle Skornicki, Patricia Prince, Robert Suruki, Edward Lee and Anthony Louder.

Prior Presentation

This manuscript is based on work that has been previously presented at the American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting, June 12–14 2020, and the British Society for Rheumatology Annual Meeting, April 20–22 2020.

Disclosures

Michelle Skornicki, Patricia Prince and Anthony Louder are employees of Aetion Inc. Robert Suruki is an employee of UCB Pharma and shareholder in UCB Pharma and GSK. Edward Lee is an employee of UCB Pharma and shareholder in UCB Pharma.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

As this database consists of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) compliant de-identified data, no ethics committee approval was required.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as data from non-interventional studies is outside of UCB’s data sharing policy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Skornicki, M., Prince, P., Suruki, R. et al. Clinical Burden of Concomitant Joint Disease in Psoriasis: A US-Linked Claims and Electronic Health Records Database Analysis. Adv Ther 38, 2458–2471 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01698-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01698-7