Abstract

Venous leg ulcers (VLUs) are the most severe manifestation of chronic venous disease (CVD). Due to their chronic nature, high recurrence rate and slow healing time, VLUs account for 80% of all leg ulcers seen in patients with CVD. VLUs impose a heavy burden on patients that reduces their quality of life; VLUs also represent a major socioeconomic impact due to the cost and duration of care. The primary medical approach to treating VLUs is local compression therapy in combination with venoactive drug (VAD) pharmacotherapy to promote the reduction of the inflammatory reaction initiated by venous hypertension. Micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF; Daflon®) is the most widely prescribed VAD. MPFF counteracts the pathophysiologic mechanisms of CVD and ulceration and has proven to be an effective adjunct to compression therapy in patients with large and chronic VLUs. Two other non-VAD drugs, pentoxifylline and sulodexide, have also been shown to improve VLU healing and are also recommended in addition to compression therapy. However, MPFF is the only VAD with the highest strength of recommendations in the 2018 guidelines for the healing of VLUs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Venous leg ulcers (VLUs) are the most severe manifestation of chronic venous disease (CVD), which, due to their chronic nature, high recurrence rate and slow healing time, account for 80% of all leg ulcers. |

VLUs impose a heavy burden on patients that reduces their quality of life and represents a major socioeconomic impact due to the cost and duration of care. |

The primary medical approach to treating VLUs is using local compression therapy in combination with venoactive drug (VAD) pharmacotherapy to promote the reduction of the inflammatory reaction initiated by the venous hypertension. |

Micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF; Daflon®) is the most widely prescribed VAD, which counteracts the pathophysiologic mechanisms of CVD and ulceration and has proven to be an effective adjunct to compression therapy in patients with large and chronic VLUs. |

Two other drugs, pentoxifylline and sulodexide, both of which are not VADs, have also been shown to improve VLU healing and are recommended in addition to compression therapy. However, MPFF has been the only VAD with the highest recommendations in the 2018 guidelines for the healing of VLUs. |

Introduction

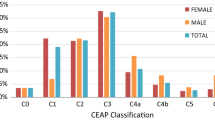

Patients with the most severe forms of chronic venous disease (CVD) and insufficiency (CVI) present with healed or active venous leg ulcers (VLUs) [Clinical Etiological Anatomical Pathophysiological (CEAP) classification classes C5 and C6, respectively; Table 1]. A VLU is defined as an open skin lesion of the leg or foot that occurs in an area affected by venous hypertension [1]. VLUs represent up to 80% of all leg ulcers and have a prevalence of approximately 1% in the general population, although this prevalence increases with age [2, 3]. Because they are chronic, slow to heal and have a high rate of recurrence within 6 months (50–70%), VLUs impose a heavy burden on patients and substantially reduce their quality of life (QoL). VLUs also have a major socioeconomic impact due to the cost and duration of care (10,000 to 12,000 USD/year per patient) and can account for up to 1% of national healthcare budgets [2, 4, 5]. Indirect burdens and costs are also large because of lost productivity of patients and family members who provide home care, premature disability and other factors [4]. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Progression of CVD to VLU

The pathophysiology of VLUs is the culmination of CVD progression that begins with venous reflux or obstruction. Progression leads to poor venous return, venous hypertension, damage to venous valves and chronic inflammation [6, 7]. The chronic edema that develops as a result increases capillary permeability and lymphatic damage to the superficial veins and skin. Pathologic skin changes along with reduced capillary blood flow and capillary leakage contribute to the breakdown of the epidermis and lead to ulceration. Patients with CVD are prone to progression, with the disease expected to worsen in 50% of those affected [3]. In patients with varicose veins, 30% develop skin changes over time indicating progression to chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) and a high risk of ulceration [8]. CVD tends to progress faster in patients that have a history of deep venous thrombosis [9]. This is likely due to venous hypertension and reflux, which are more severe in these patients, stemming from persistent obstruction, damaged veins and/or valvular incompetence.

Medical Management of VLU: Compression and Venoactive Drug Therapy

The medical management of VLU includes a careful assessment of the venous systems responsible to identify incompetent perforating and deep veins. Dressings and compression therapy are generally the primary therapeutic option, followed by surgery, if necessary, to remove incompetent veins [10, 11]. Intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) has improved healing rates in some studies when used with standard compression [12], but it is not yet clear whether it is superior to standard compression and for which patients it is most beneficial. At present, IPC is recommended for patients with VLUs that have failed to heal with standard compression therapy or for patients who cannot tolerate compression stockings or bandages [10].

Many studies have aimed to determine the associations and effects of nutritional characteristics on VLU outcomes. Patients with VLU tend to be overweight or obese, which may mask nutritional deficiencies impacting on VLU healing and recurrence. Zinc intake was found to be below recommendations in a minority of VLU patients. Other nutritional characteristics of VLU patients included low levels of serum vitamin D, vitamin C and zinc as well as fatty acid imbalances [13]. In a meta-analysis of 20 studies, vitamin D, folic acid and flavonoids were associated with some beneficial effects on ulcer healing [14]. However, dietary supplements have not been shown to be efficient therapies for VLU, and further investigation into the role of micronutrient deficiencies in wound healing is needed.

Systemic treatment with venoactive drugs (VADs) in combination with compression can be highly effective in healing VLUs [10, 15]. Adjunct treatment with VAD can decrease the inflammation associated with venous hypertension, promote VLU healing and improve QoL. Micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF; Daflon®) is the most widely prescribed VAD to treat CVD. The pharmacologic actions of MPFF include reductions in endothelial cell activation, serum concentrations of endothelial cell adhesion molecules and growth factors, leukocyte adhesion and activation, venous valve deterioration and reflux, proinflammatory mediator production and release, and capillary leakage [7, 10]. These properties result in clinical benefits that improve venous tone and the clinical signs and symptoms of CVD, edema, skin changes, VLU healing and QoL [10]. Side effects of MPFF are infrequent and minor.

Evidence that MPFF treatment improves VLU healing comes from a meta-analysis of five randomized clinical trials (RCT) involving 723 VLU patients [15]. Comparisons were made between patients receiving MPFF in addition to conventional treatment (compression and local care) and patients receiving conventional treatment only or with placebo, with a primary end point of complete ulcer healing after 6 months. Adjunct MPFF treatment led to an overall healing rate of 61.3% and was associated with a statistically significant increase of 32% in the chance that a VLU would be healed within 6 months over conventional treatment alone (47.6% healing rate; P = 0.03). Adjunct MPFF treatment also increased the chances of healing for VLUs that were > 5 cm2 (53%; P = 0.035) and for VLUs that had persisted between 6 and 12 months (44%; P = 0.021). Time to healing was also significantly shorter with MPFF treatment (16.1 weeks) than without (21.3 weeks; P = 0.003).

Such evidence has led to high-level recommendations for the use of MPFF therapy in VLU treatment across multiple international treatment guidelines since 2008 (Table 2). MPFF in addition to standard care is recommended for healing of venous ulcers (CEAP C6), for healing of venous ulcers due to post-thrombotic syndrome and for long-standing or large VLU.

Two other drugs, pentoxifylline and sulodexide, both of which are not VADs, have also been shown to improve VLU healing and are recommended in addition to compression therapy [10]. Pentoxifylline, a methylated xanthine derivative, is a competitive non-selective phosphodiesterase inhibitor that has been shown to have antioxidant properties and to reduce inflammation. In addition, pentoxifylline reduces blood viscosity and decreases the potential for platelet aggregation and blood clot formation. Sulodexide, a combination of fast-moving heparin and dermatan sulfate, also has antithrombotic and profibrinolytic properties as well as antiinflammatory effects. In a 2012 Cochrane Review of 11 RCTs, pentoxifylline alone was more effective than placebo for complete ulcer healing or significant improvement [relative risk (RR) 1.70; 95% CI 1.30–2.24], while compression was more effective with pentoxifylline than with placebo (RR 1.56; 95% CI 1.14–2.13). In the 2016 Cochrane Review investigating sulodexide treatment, combined complete ulcer healing rates were 49.4% with conventional treatment plus sulodexide and 29.8% with conventional compression treatment alone for a relative risk ratio of RR 1.66 (95% CI 1.30–2.12) [16]. Almost identical results were obtained from another analysis that included two additional studies [17].

In the current European CVD management guidelines (2018), high levels of evidence (grade A) are cited to recommend MPFF, pentoxifylline and sulodexide treatments in the healing of VLUs as an adjunct to compression therapy [10]. MPFF, however, is the only VAD with such a recommendation.

Conclusions

VLUs are the most severe manifestations of CVD. In patients with varicose veins, 30% will develop skin changes associated with CVI, which will increase their risk of developing a venous ulcer. The mainstay of VLU management is local treatment plus compression therapy with stockings, bandages or IPC and should include pharmacotherapy to promote healing by reducing the inflammatory reaction initiated by the venous hypertension. Thanks to its pharmacologic activities that counteract the pathophysiologic mechanisms of CVD and ulceration, in particular its antiinflammatory effects, MPFF is an effective adjunct to compression therapy in patients with large and chronic VLUs. Patients receiving MPFF treatment for VLU also stand to benefit from reduced CVD symptoms, better venous tone and improved QoL.

References

O’Donnell TF Jr, Passman MA, Marston WA, Ennis WJ, Dalsing M, Kistner RL, et al. Management of venous leg ulcers: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery (R) and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60(2 Suppl):3s–59s.

Ruckley CV. Socioeconomic impact of chronic venous insufficiency and leg ulcers. Angiology. 1997;48(1):67–9.

Lee AJ, Robertson LA, Boghossian SM, Allan PL, Ruckley CV, Fowkes FG, et al. Progression of varicose veins and chronic venous insufficiency in the general population in the Edinburgh Vein Study. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2015;3(1):18–26.

O’Donnell TF Jr, Passman MA. Clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) and the American Venous Forum (AVF) management of venous leg ulcers. Introduction. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60(2 Suppl):1S–2S.

O’Donnell TF Jr, Balk EM. The need for an intersociety consensus guideline for venous ulcer. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54(6):83S–90S.

Dabiri G, Hammerman S, Carson P, Falanga V. Low-grade elastic compression regimen for venous leg ulcers–an effective compromise for patients requiring daily dressing changes. Int Wound J. 2015;12(6):655–61.

Mansilha A, Sousa J. Pathophysiological mechanisms of chronic venous disease and implications for venoactive drug therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(6):1669.

Robertson LA, Evans CJ, Lee AJ, Allan PL, Ruckley CV, Fowkes FG. Incidence and risk factors for venous reflux in the general population: Edinburgh Vein Study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2014;48(2):208–14 (The official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery).

Lozano Sanchez FS, Gonzalez-Porras JR, Diaz Sanchez S, Marinel Lo Roura J, Sanchez Nevarez I, Carrasco EC, et al. Negative impact of deep venous thrombosis on chronic venous disease. Thromb Res. 2013;131(4):e123–6.

Nicolaides A, Kakkos S, Baekgaard N, Comerota A, de Maesenner M, Eklof B, et al. Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs. Guidelines according to scientific evidence part I. Int Angiol. 2018;37(3):181–254.

Gohel MS, Heatley F, Liu X, Bradbury A, Bulbulia R, Cullum N, et al. A randomized trial of early endovenous ablation in venous ulceration. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2105–14.

Nelson EA, Hillman A, Thomas K. Intermittent pneumatic compression for treating venous leg ulcers. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014(5):CD001899.

Tobon J, Whitney JD, Jarrett M. Nutritional status and wound severity of overweight and obese patients with venous leg ulcers: a pilot study. J Vasc Nurs. 2008;26(2):43–52.

Barber GA, Weller CD, Gibson SJ. Effects and associations of nutrition in patients with venous leg ulcers: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(4):774–87.

Coleridge-Smith P, Lok C, Ramelet AA. Venous leg ulcer: a meta-analysis of adjunctive therapy with micronized purified flavonoid fraction. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;30(2):198–208.

Wu B, Lu J, Yang M, Xu T. Sulodexide for treating venous leg ulcers. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2016(6):CD010694.

Coccheri S, Bignamini AA. Pharmacological adjuncts for chronic venous ulcer healing. Phlebology. 2016;31(5):366–7.

Nicolaides AN, Allegra C, Bergan J, Bradbury A, Cairols M, Carpentier P, et al. Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs: guidelines according to scientific evidence. Int Angiol. 2008;27(1):1–59 (A journal of the International Union of Angiology).

Kearon C, Kahn SR, Agnelli G, Goldhaber S, Raskob GE, Comerota AJ. Antithrombotic therapy for venous thromboembolic disease: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):454S–545S.

Nicolaides A, Kakkos S, Eklof B, Perrin M, Nelzen O, Neglen P, et al. Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs guidelines according to scientific evidence. Int Angiol. 2014;33(2):87–208.

Wittens C, Davies AH, Baekgaard N, Broholm R, Cavezzi A, Chastanet S, et al. Editor’s choice management of chronic venous disease: clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;49(6):678–737.

Gloviczki P, editor. Handbook of venous and lymphatic disorders: guidelines of the American Venous forum, fourth edition. 4th ed. London: CRC Press; 2017.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This supplement has been sponsored by Servier. The journal’s Rapid Service and open access fees were funded by Servier.

Medical Writing

Medical writing services were provided by Dr. Kurt Liittschwager (4Clinics, France) and were funded by Servier.

Authorship

Dr. Andrew N. Nicolaides meets the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and has approved this version for publication.

Prior Presentation

This article and all of the articles in this supplement are based on the international satellite symposium at the European Venous Forum (June 2019, Zurich, Switzerland).

Disclosures

Dr. Andrew N. Nicolaides declares having received speaker honoraria from Medtronic, Servier, Pierre Fabre and Alfasigma.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11417571.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nicolaides, A.N. The Most Severe Stage of Chronic Venous Disease: An Update on the Management of Patients with Venous Leg Ulcers. Adv Ther 37 (Suppl 1), 19–24 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-020-01219-y

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-020-01219-y