Abstract

Chronic venous disease (CVD) is one of the most prevalent diseases worldwide. The health condition of most patients with early stage CVD will worsen over time, and this progression increases the burden as well as the costs of treatment and reduces patient quality of life (QoL). This highlights the importance and the likely cost-effectiveness of treatment of patients with early stage CVD. Options for managing the early stages of CVD include lifestyle changes together with venoactive drugs (VAD); VADs may be used alone or in conjunction with interventional treatment of varices such as sclerotherapy, surgery, or endovenous treatments. Micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF; Daflon®) is a well-studied VAD which has anti-inflammatory activities, reduces endothelial activation and leukocyte adhesion, and increases capillary resistance and integrity, to eventually improve venous tone, CVD symptoms and QoL. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Chronic venous disease (CVD) is one of the most prevalent diseases worldwide as varicose veins are present in 25–40% of adults, while the more serious condition of chronic venous insufficiency has a prevalence of 17–20%. |

The health condition of most patients with early stage CVD will worsen over time, and this progression increases the burden as well as the costs of treatment and reduces patient quality of life (QoL), which points to the importance and the likely cost-effectiveness of treating patients with early stage CVD. |

Options for managing the early stages of CVD include venoactive drugs (VAD), which may be used alone or in conjunction with interventional treatment of varices such as sclerotherapy, surgery, or endovenous treatments. |

Micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF; Daflon®) is a well-studied VAD which has anti-inflammatory activities, reduces endothelial activation and leukocyte adhesion, and increases capillary resistance and integrity, to eventually improve venous tone, CVD symptoms and QoL. |

Chronic venous disease (CVD) is one of the most prevalent diseases worldwide. Varicose veins (Clinical-Etiological-Anatomical-Pathophysiological (CEAP) classification class C2; see Table 1) are present in 25–40% of adults, depending on risk factors [1], whereas the more serious condition of chronic venous insufficiency (CVI; CEAP C3–C6) has a prevalence 17–20% [1, 2]. CVD tends to worsen over time, especially if left untreated. In the Edinburgh Vein Study, CVD progressed in more than 57% of the patients with varicose veins or CVI over 13 years of follow-up [3].

The aim of this review is to emphasize the importance of treating the chronic venous disease from the early stages, with medical treatment alone or in addition to different treatment modalities that include sclerotherapy, endovenous or surgery.

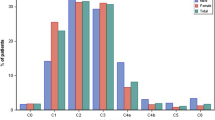

Depending on disease severity, patients with CVD seek treatment for a variety of symptoms including pain or aching, throbbing, leg heaviness, feelings of swelling, muscle fatigue, itching, and cramps. Patients may also seek cosmetic treatment to eliminate varicose veins and spider veins (telangiectasia). Patients with early stage CVD (C0s) have disease-related symptoms (heavy legs in the upright position, restless leg syndrome, subedema, and/or evening edema) but have no clinical signs. As the disease progresses, patients develop telangiectasia (C1), varicose veins (C2), edema (C3), skin pigmentation, eczema or lipodermatosclerosis (C4), or venous ulcers (C5–C6).

CVD progresses as a result of a persistent inflammatory cycle that typically begins with abnormal venous flow due to venous hypertension and damaged venous valves. Aberrant hemodynamics and reflux activate the venous endothelium, leading to infiltration of activated leukocytes into the vein walls and surrounding tissues, where inflammatory cytokines and mediators are released [4]. These events, along with persistent vein dilatation, lead to further structural changes and deterioration in the veins and valves, reduced venous flow and return, all of which increase venous hypertension and subsequent inflammatory responses.

Options for management of patients at the early stages of CVD (C0s to C2) include venoactive drugs (VAD), which may be used alone or in conjunction with interventional treatment of varices such as sclerotherapy, surgery, or endovenous treatments [1]. Management objectives for patients with CVD are to alleviate venous symptoms and signs, break the inflammatory cascade, and prevent progression into a higher CEAP clinical class. There is a strong rationale for the management of mildly symptomatic patients who have early stage CVD (C0s). Early intervention, including recommendations for lifestyle changes (e.g., loss of weight, increase in physical activity, wearing of low-heeled shoes) and treatment may slow disease progression, thus preventing or delaying the onset of more serious symptoms and irreversible venous structural changes.

The anatomical or pathophysiological causes of venous symptoms in C0s patients, which represented up to 20% of patients with CVD in the worldwide Vein Consult Program [2], are not completely understood. A pilot study using high-sensitivity Doppler analysis found that bidirectional reflux in small second- to sixth-generation tributaries and small non-saphenous veins tended to be more prevalent in C0 patients than in asymptomatic ones (P = 0.05) [5]. These results suggest that abnormal venous flow is already present in early stage CVD, supporting a role for early treatment. Further investigations should assess the potential benefits of medical treatment at the earliest stages of CVD.

For patients with telangiectasias, reticular veins, and varicose veins, the routine treatment options include compression therapy; medical treatment with VAD alone or in combination with compression; ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy; transcutaneous laser; endovenous thermal, laser, radiofrequency, or steam ablation; cyanoacrylate glue; and surgical removal. Micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF; Daflon®) is the most well-known and most well-studied VAD for medical treatment. Pharmacologically, MPFF has anti-inflammatory activities, reduces endothelial activation and leukocyte adhesion, and increases capillary resistance and integrity [4]. As a result of these effects, MPFF produces a number of significant clinical benefits in patients with CVD. It improves CVD symptoms, venous tone, skin trophic disorders and quality of life (QoL). It also reduces leg edema and speeds ulcer healing [1, 4, 6]. In the latest international guidelines, MPFF was given a grade 1B recommendation for overall relief of symptoms and edema associated with all CEAP classes of CVD (C0s to C6), and a grade 1A or 1B for individual symptoms, QoL (1A), and ulcer healing (1A).

MPFF treatment alone has been shown to benefit patients with early stage CVD. In C0s women with evening leg symptoms due to reflux in the greater saphenous vein (GSV), 2 months of MPFF treatment decreased the number of patients with evening (situational) reflux by 85% compared to baseline [7]. In addition, the mean evening GSV diameter decreased significantly from 6.33 (4.50–8.00) mm to 5.50 (1.10–7.00) mm (P < 0.0001), with a significant reduction in the difference between the morning and evening diameters (P < 0.0001). These physiological changes were accompanied by substantial reductions in evening symptoms of leg heaviness, cramps, and pain and were associated with significant improvement in CIVIQ-20 QoL scores (57.97 ± 7.63 vs 69.64 ± 8.65; P < 0.0001). In a similar study, 3 months of MPFF treatment (1000 mg/day) in women (N = 53) with telangiectasia and/or reticular varices and evening situational reflux resulted in the absence or resolution of evening reflux in 92.5% of the women and a significant reduction in evening diameters of the GSV [8]. All women reported symptom improvement: leg heaviness and fatigue were either eliminated (88.6%) or reduced (11.4%), pain was eliminated (100%), and night cramps ceased (94.3%) or were substantially reduced (5.6%).

The combined benefits of MPFF treatment with or without surgery were investigated in women patients with C0s, C1, or C2 CVD with situational GSV reflux [9]. MPFF treatment alone (1000 mg/day for 90 days) eliminated evening GSV reflux in 76.1% of the C0s and C1 patients, whereas MPFF treatment subsequent to surgery reduced (60%) or resolved (40%) reflux in all of the C2 patients in whom GSV reflux persisted after surgery.

MPFF has also been shown to reduce the severity of CVD symptoms and signs after endovenous treatment [ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS), endovenous laser ablation (EVLA), or radiofrequency ablation (RFA)]. In C2–C4 patients, venous clinical severity scores (VCSS) at 2 weeks after an endovenous procedure were significantly lower than baseline scores in the group of patients treated with MPFF (N = 126; 1000 mg/day) for 2 weeks before the procedure and 4 days afterward (3.3 vs 4.2, P < 0.001) but not in the untreated control group (N = 104; 3.7 vs 4.0, P = 0.15) [10]. QoL at 30 days improved in both groups with no significant difference between groups. In a similar study, the vein-specific symptoms of leg heaviness, pain, swelling sensations, night cramps, and itching in C1 patients undergoing sclerotherapy plus the same MPFF treatment regimen (N = 905) all improved to a significantly greater degree than in patients treated with sclerotherapy alone (N = 245) [11]. In this study, improvements in QoL assessed by CIVIQ-14 scores were significantly greater with MPFF treatment than without.

The benefits of MPFF treatment in patients undergoing sclerotherapy may be linked to its anti-inflammatory activity. Bogachev et al. examined the levels of a number of inflammatory markers present in the vascular clusters adjacent to veins treated with sclerotherapy in C1 patients treated or not treated with MPFF (1000 mg/day for 2 week before and 2 months after sclerotherapy) [12]. At 10 days after sclerotherapy, venous concentrations of C-reactive protein, histamine, and interleukin-1 were all significantly lower in the MPFF treatment group than in the control group. Concentrations of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and vascular endothelial growth factor were significantly higher than baseline in control patients but not in patients treated with MPFF.

However, while sclerotherapy is appropriate for C1 patients with telangiectasia, the European Society for Vascular Surgery recommends surgical treatment for C2 and C3 patients with non-complicated varicose veins [13]. Thus, what is the evidence that VAD can benefit patients whose varicose veins warrant endovenous treatment or surgical removal? Recently, this question was examined in a systematic review of the literature [14]. Although over 200 records were retrieved in the search, only five clinical trials that investigated the effects of VAD treatment on recovery after surgery, endovenous ablation, or sclerotherapy in patients with C2 or greater CVD were appropriate for analysis. All of the studies had limitations with respect to randomization and/or blinding, and none included a placebo control group. MPFF was used in all of the studies and sulodexide was also used in one study. In the analysis, MPFF treatment was associated with significant benefits in pain relief (three out of four studies), reduced hematoma or hemorrhage (two out of two studies), and improvement in CVD symptoms (three out of four studies). With so few studies of limited quality, it is not yet possible to make definitive conclusions on whether MPFF treatment is beneficial to patients recovering from a surgical or endovenous procedure. However, the overall consistency of these preliminary results suggests a positive trend and warrants further study of MPFF in randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trials in patients recovering from such procedures.

In most patients with early stage CVD, their condition will worsen over time. Disease progression increases the burden and costs of treatment and reduces patient QoL. Although there are known risk factors, it is not yet possible to determine in which individuals CVD will progress, how rapidly it will worsen, or the extent of the progression. Thus, it is important and likely cost-effective to treat patients with early stage CVD, conservatively with VAD at the earliest stages (C0s, C1) to alleviate symptoms and improve venous tone, and with endovenous interventions or surgery in patients that develop varicose veins (C2). In the latter group of patients, there is now promising evidence that post-procedural treatment with VAD, such as MPFF, may help reduce pain, hemorrhage, and CVD-specific symptoms. These benefits appear to be greater if the treatment begins 2 weeks prior to the procedure.

In conclusion, VAD have proven clinical benefits in patients with CVD and can be used alone and in addition to endovenous procedures and surgical treatment.

References

Nicolaides A, Kakkos S, Baekgaard N, et al. Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs. Guidelines according to scientific evidence. Part I. Int Angiol. 2018;37(3):181–254.

Rabe E, Guex JJ, Puskas A, Scuderi A, Fernandez QF. Epidemiology of chronic venous disorders in geographically diverse populations: results from the Vein Consult Program. Int Angiol. 2012;31(2):105–15.

Lee AJ, Robertson LA, Boghossian SM, et al. Progression of varicose veins and chronic venous insufficiency in the general population in the Edinburgh Vein Study. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2015;3(1):18–26.

Mansilha A, Sousa J. Pathophysiological mechanisms of chronic venous disease and implications for venoactive drug therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(6):1669.

Lugli M, Maleti O, Iabichella ML, Perrin M. Investigation of non-saphenous veins in C0S patients. Int Angiol. 2018;37(2):169–75.

Kakkos SK, Nicolaides AN. Efficacy of micronized purified flavonoid fraction (Daflon®) on improving individual symptoms, signs and quality of life in patients with chronic venous disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials. Int Angiol. 2018;37(2):143–54.

Tsoukanov YT, Tsoukanov AY, Nikoiaychuk A. Great saphenous vein transitory reflux in patients with symptoms related to chronic venous disorders, but without visible signs (C0s), and its correction with MPFF treatment. Phlebolymphology. 2017;22(1):3–11.

Tsukanov YT, Nikolaichuk AI. Orthostatic-loading-induced transient venous refluxes (day orthostatic loading test), and remedial effect of micronized purified flavonoid fraction in patients with telangiectasia and reticular vein. Int Angiol. 2017;36(2):189–96.

Tsukanov YT, Tsukanov AY. Diagnosis and treatment of situational great saphenous vein reflux in daily medical practice. Phlebolymphology. 2017;24(3):144–51.

Bogachev VY, Golovanova OV, Kuzhetsov AN, Shekoian AO, the DECISION Investigators group. Can micronized purified flavonoid fraction* (MPFF) improve outcomes of lower extremity varicose vein endovenous treatment? First results from the DECISION study. Phlebolymphology. 2013;20(4):181–7.

Bogachev VY, Boldin BV, Turkin PY. Administration of micronized purified flavonoid fraction during sclerotherapy of reticular veins and telangiectasias: results of the national, multicenter, observational Program VEIN ACT PROLONGED-C1. Adv Ther. 2018;35(7):1001–8.

Bogachev VY, Boldin BV, Lobanov VN. Benefits of micronized purified flavonoid fraction as adjuvant therapy on inflammatory response after sclerotherapy. Int Angiol. 2018;37(1):71–8.

Wittens C, Davies AH, Baekgaard N, et al. Editor’s choice—management of chronic venous disease: clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;49(6):678–737.

Mansilha A, Sousa J. Benefits of venoactive drug therapy in surgical or endovenous treatment for varicose veins: a systematic review. Int Angiol. 2019;38:291–8.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This supplement has been sponsored by Servier. Article processing charges and the open access fee were funded by Servier.

Medical Writing

Medical writing services were provided by Dr. Kurt Liittschwager (4Clinics, France) and were funded by Servier.

Authorship

Dr. Armando Mansilha meets the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and has approved this version for publication.

Prior Presentation

This article and all of the articles in this supplement are based on the international satellite symposium at the European Venous Forum (June 2019, Zurich, Switzerland).

Disclosures

Professor Armando Mansilha reports consulting, honoraria or speaker fees from Servier, Alfa Sigma, OM Pharma and Bayer.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11417631.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mansilha, A. Early Stages of Chronic Venous Disease: Medical Treatment Alone or in Addition to Endovenous Treatments. Adv Ther 37 (Suppl 1), 13–18 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01217-9

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01217-9