Abstract

Introduction

Apalutamide and enzalutamide are next-generation androgen receptor inhibitors that demonstrated efficacy in placebo-controlled studies (SPARTAN for apalutamide; PROSPER for enzalutamide) when used in combination with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for treatment of non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC). In the absence of comparative studies between these agents, the present study sought to indirectly compare metastasis-free survival (MFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with nmCRPC who received these therapies.

Methods

Individual patient-level data from SPARTAN (apalutamide plus ADT) and published data from PROSPER (enzalutamide plus ADT) were utilized. An anchored matching-adjusted indirect comparison (MAIC) was conducted by weighting the patients from the SPARTAN study to match baseline characteristics reported for PROSPER. Hazard ratios (HRs) for MFS and OS were re-estimated for SPARTAN using weighted Cox proportional hazards models and indirectly compared with those of PROSPER using a Bayesian network meta-analysis.

Results

From the SPARTAN population (N = 1207), a total of 1171 patients were matched to the PROSPER population (N = 1401). The recalculated HRs (95% confidence interval) for apalutamide versus ADT based on the reweighted SPARTAN data to mimic the PROSPER patient population were 0.26 (0.21; 0.33) for MFS and 0.62 (0.41; 0.94) for OS. MAIC-based HRs (95% credible interval) for apalutamide versus enzalutamide were 0.91 (0.68; 1.22) for MFS and 0.77 (0.46; 1.30) for OS. The Bayesian probabilities of apalutamide being more effective than enzalutamide were 73.6% for MFS and 83.5% for OS.

Conclusions

MAIC results suggest that nmCRPC patients treated with apalutamide have a higher probability of a more favorable MFS and OS compared with those treated with enzalutamide.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Apalutamide and enzalutamide are next-generation androgen receptor inhibitors approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC) |

Both apalutamide (SPARTAN) and enzalutamide (PROSPER) have been studied in combination with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) in placebo-controlled studies in men with nmCRPC, but no studies have directly compared metastasis-free survival (MFS) and overall survival (OS) associated with these agents |

What did the study ask? |

The present study sought to indirectly compare MFS and OS for these agents |

What was learned from the study? |

Results from the present matching-adjusted indirect comparison suggest that nmCRPC patients treated with apalutamide have a higher probability of a more favorable MFS and OS compared with those who received enzalutamide |

Introduction

While androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) has been part of the standard treatment for prostate cancer for decades, most men become resistant to this treatment over time and develop castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) [1]. Over the past years, new treatments for CRPC have been investigated for patients in the metastatic state [2, 3].

Preventing or delaying progression to metastatic disease is an area of unmet clinical need among patients with non-metastatic CRPC (nmCRPC) [4]. Two next-generation androgen receptor inhibitors, apalutamide and enzalutamide, respectively, have been studied in the phase III SPARTAN and PROSPER randomized, placebo-controlled clinical studies in patients with nmCRPC who were at a high risk of developing metastasis [defined by rapidly rising prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels], and data supporting achievement of primary endpoints have been published [5, 6]. Based on the results of these studies, apalutamide and enzalutamide have both recently been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (February 2018, and July 2018, respectively) for nmCRPC treatment based on metastasis-free survival (MFS) as the primary efficacy endpoint [5, 6]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the American Urological Association, and the European Association of Urology recommend that clinicians offer apalutamide or enzalutamide with continued ADT to patients with nmCRPC at high risk of developing metastases, as defined by a PSA doubling time (PSADT) of ≤ 10 months [7,8,9], while French guidelines recommend the use of apalutamide or enzalutamide with continued ADT to patients with nmCRPC regardless of the risk of progression [10].

In both the SPARTAN and PROSPER studies, MFS results were statistically significant, while analyses on overall survival (OS) showed a consistent trend without reaching statistical significance because of the immature OS data in both studies [5, 6]. A total of 1207 patients were randomized in SPARTAN. In the primary analysis, apalutamide + ADT (hereafter referred to as apalutamide) was associated with a significant 72% reduction in risk of metastasis or death compared with placebo + ADT (ADT; p < 0.001). In addition, apalutamide was associated with a non-significant 30% reduction in risk of death compared with ADT at the first interim analysis (p = 0.07) [6]. In PROSPER, 1401 participants were randomized. In primary analyses, enzalutamide + ADT (hereafter referred to as enzalutamide) significantly reduced the risk of metastasis or death by 71% compared with ADT (p < 0.001). Enzalutamide was associated with a 20% lower risk of death at the first interim analysis though this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.15) [5].

A recent meta-analysis combining evidence from both studies showed a statistically significant OS benefit across both treatments, assuming a class effect [11]. It is important to note that this meta-analysis was based on a random effects model, which conceptually allows variability in treatment effect between both treatments within the class. This variability in treatment effect within the class is the scope of the current analysis.

Indirect comparisons that rely on aggregate data without accounting for differences between the studies in patient baseline characteristics are prone to significant bias because of differences in study populations [12, 13]. This potential for bias is largely overcome using a matching-adjusted indirect comparison (MAIC), which reweights individual patient data (IPD) for one study so that measured baseline characteristics in this study match the aggregate baseline characteristics reported for the study of the comparator treatment [14, 15]. The method corrects for potential biases caused by imbalances in patient characteristics that may have an impact on the relative treatment effect, allowing for indirect comparison with limited bias [16]. MAIC modeling has provided strong comparative evidence in the absence of head-to-head studies in various disease settings [17,18,19]. When studies use the same comparator, such as placebo plus ADT in the case of SPARTAN and PROSPER, MAIC is considered an appropriate methodology to examine comparative effectiveness [16].

This study aims to compare the efficacy of both treatments using the MAIC method, which enables the comparison between IPD for one drug and published data for another drug [15].

Methods

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of humans on either therapy. This study used IPD from the SPARTAN study [20] and aggregate data from the PROSPER study [5]. The efficacy analyses were based on the intent-to-treat (ITT) populations from both studies, which included adult men with nmCRPC. The SPARTAN ITT population included 1207 patients (806 randomized to the apalutamide arm and 401 to the ADT arm) [20], whereas the PROSPER ITT population included 1401 patients (933 randomized to the enzalutamide arm and 468 to the ADT arm) [5].

The definitions and assessment methods of the endpoints used in the SPARTAN and PROSPER studies were reviewed to determine comparability of endpoints between the two studies. Since MFS was defined differently in the two studies, the present study used the PROSPER study definition of MFS, which was the time from randomization to radiographic progression or death within 112 days of treatment discontinuation.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4, R 3.5.0, and Winbugs 1.4.3. An anchored MAIC analysis was performed by using IPD from SPARTAN and published aggregate baseline data from PROSPER to match SPARTAN patient characteristics to those in PROSPER via inverse probability weighting. This step aimed to use SPARTAN patients to create a population identical to that of PROSPER and to indirectly compare efficacy endpoints between patients initiated on either apalutamide or enzalutamide.

All clinically relevant baseline characteristics reported in PROSPER that could potentially affect relative treatment effects were considered in the matching process. In this approach, individual patients enrolled in SPARTAN were assigned weights such that: (1) the weighted mean or median baseline characteristics in SPARTAN closely matched those reported in PROSPER, and (2) each patient’s weight was equal to his estimated odds of enrollment in SPARTAN versus PROSPER. Weights meeting these conditions were obtained from a logistic regression model for the propensity of enrollment in SPARTAN versus PROSPER, estimated using the method of moments as described by Signorovitch et al. [15]. The baseline characteristics adjusted for included age, baseline PSA and PSADT, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, total Gleason score, use of bone-targeting agents, and baseline history of surgical prostate cancer procedures. Patients from SPARTAN missing any of the matched-on characteristics were excluded from the sample.

Step 1: Recalculation of Hazard Ratios from SPARTAN

In a first step, re-analysis of the SPARTAN study endpoints comparing apalutamide and ADT was conducted using the SPARTAN MAIC-weighted population. A weighted Cox proportional hazards regression analysis using a robust estimator for the variance was performed to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) for the endpoints of interest for apalutamide versus ADT with the MAIC-weighted SPARTAN study data, applying the definition of MFS as used in the PROSPER study. A sensitivity analysis was performed using the original SPARTAN publication MFS definition (original SPARTAN MFS) [20].

Step 2: Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis

In a second step, the updated HRs for SPARTAN estimated in the previous step were compared with the reported HRs from PROSPER to estimate the HRs for apalutamide versus enzalutamide using a Bayesian framework [15, 21] with ADT as the common comparator across both studies. Bayesian models were used to compare MFS and OS in the two studies. Non-informative prior distributions were used. Due to the limited number of studies in the networks, only fixed-effects models are presented, and random-effects models were not considered because of a lack of information to estimate between-study variability. These analyses were conducted according to the methods described in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Decision Support Unit Technical Support Documents [22, 23]. The prior probability distributions were chosen based on the NICE recommendations [22, 23].

Results

Prior to matching, the SPARTAN and PROSPER patient populations differed regarding median PSADT (4.4 vs. 3.7 months) and percentage of patients with PSADT < 6 months (70% vs. 77%). Compared with the PROSPER population, the unmatched SPARTAN population had lower median serum PSA at baseline (7.80 vs. 10.80). After matching, baseline characteristics were balanced between the two studies. A total of 36 patients from SPARTAN with missing information for matched-on variables were excluded (Table 1).

Demographic and disease characteristics of the original and MAIC-weighted SPARTAN populations are presented by treatment arm in Supplemental Table S1.

Metastasis-Free Survival

MFS HR Comparison of Apalutamide Versus ADT Based on Reweighted SPARTAN Study

The HRs for MFS using the definition from PROSPER were similar before matching {HR [95% confidence interval (CI)] 0.27 (0.22; 0.33), p < 0.001} and after matching [HR (95% CI) 0.26 (0.21; 0.33), p < 0.001]. HRs were nearly identical when using the original definition of MFS from SPARTAN (Table 2).

MFS HR Comparison of Apalutamide Versus Enzalutamide Based on Anchored MAIC

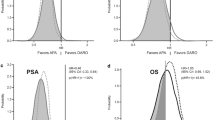

Using the MFS definition from PROSPER, the MAIC results suggest a more favorable MFS with apalutamide compared with enzalutamide {HR [95% credible interval (CrI)] 0.91 (0.68; 1.22), P(HR < 1) 73.6%}, where P is the Bayesian probability that apalutamide has MFS benefit compared with enzalutamide. Figure 1 shows the posterior distribution of the HR of MFS between apalutamide and enzalutamide, and the Bayesian probability of 73.6% is visually represented as the area under the distribution to the left of an HR 1. Using the definition of MFS in the SPARTAN study, consistent trends were observed {HR (95% CrI) 0.97 (0.72; 1.29), P[HR < 1] 59.6%; Table 3}.

Overall Survival

OS HR Comparison of Apalutamide Versus ADT Based on Reweighted SPARTAN

OS in the SPARTAN study [HR (95% CI) 0.70 (0.47; 1.04), p 0.07] improved after matching and reached statistical significance [HR (95% CI) 0.62 (0.41; 0.94), p = 0.024; Table 2]. This difference was mainly driven by the adjustment for the differences in PSADT (% with PSADT < 6 months and median PSADT), since the relative benefit of active treatment is more pronounced in patients with a shorter PSADT.

OS HR Comparison of Apalutamide Versus Enzalutamide Based on Anchored MAIC

The HR for OS was in favor of apalutamide [HR (95% CrI) 0.77 (0.46; 1.30)], with an 83.5% probability that apalutamide has greater survival benefit versus enzalutamide (Table 3). The posterior distribution of the HR of OS between apalutamide and enzalutamide is presented in Fig. 2.

Discussion

This study indirectly compares a similar definition of efficacy of apalutamide and enzalutamide when used concurrently with ADT for the treatment of men with high-risk nmCRPC using efficacy data from clinical studies of these novel hormonal treatments. After balancing important measured differences in baseline characteristics between the two studies, results suggest that among men with nmCRPC, apalutamide may have advantages for MFS and for OS compared with enzalutamide.

While the primary aim of the registration studies was to delay metastatic progression in patients with nmCRPC, OS is also regarded as a pertinent outcome among these patients. In PROSPER, 32 of 219 (15%) patients died without documented radiographic progression within 112 days of treatment discontinuation, whereas in SPARTAN, 10 of 378 (2.6%) patients died when applying the same definition [5, 6]. This difference in rates of deaths has contributed to a higher probability of apalutamide being the treatment that is more effective in preventing death in this analysis.

Recently, Wallis et al. published results from a similar indirect comparison between apalutamide and enzalutamide with objectives similar to the current manuscript, albeit with different conclusions [24]: the authors did not find any significant differences on any endpoints and concluded that both treatments are similarly effective in delaying metastases for patients with nmCRPC [24]. It is important to clarify that differences in results and conclusions are driven by differences in the methodologic approaches. Wallis et al. applied the Bucher technique [12], which is a simple, easy to implement frequentist statistics approach generating a classic CI around the point estimate with a classic p value, while the current analysis uses a Bayesian anchored MAIC approach. Indirect comparisons like the Bucher approach are assumed to generate unbiased estimates as long as no differences exist across studies in patient characteristics that have interaction with treatment (i.e., treatment effect modifiers) [25]. The present study showed that this assumption does not hold. The SPARTAN and PROSPER patient populations differ on important characteristics that do impact the relative treatment effect versus ADT. More specifically, the differences in baseline PSADT may bias results since the relative treatment effect of active treatment versus ADT is higher in patients who have shorter PSADT. This provides supporting evidence for the use of anchored MAIC, which is a commonly accepted way to address this potential bias of simple approaches to generate indirect evidence. Moreover, the methodology of the present study conforms to that described in the NICE Decision Support Unit Technical Support Documents [22, 23]. As mentioned, availability of patient-level data for one of the studies is needed to implement the approach. By reweighting the SPARTAN patient data, the HRs for apalutamide versus ADT were calculated in a patient population similar to that of the PROSPER study. This approach aims to remove the bias caused by differences between patient populations [15, 22].

A second important difference between the two approaches is the statistical approach taken and the related interpretation of the results. The Bucher approach (used by Wallis et al.) generates results in a frequentist statistics framework, which is known to lack statistical power [26]. This is because the standard error of the indirect comparison estimate is based on the simple addition of the two variances from the original studies, which always leads to more uncertainty. This often means that indirect comparisons do not reach formal statistical significance at the 5% alpha level according to the frequentist statistics interpretation, while there are clear indications of differences between treatments. A conventional frequentist approach, like that applied by Wallis et al., dichotomizes results to be either significant or non-significant, based on the chosen significance level. This is not well suited for decision-making, as it does not indicate the probability of the hypothesis being true or false. Given that both treatments are available to patients without a formal head-to-head comparison, the more relevant question is, “How likely it is that, provided the available evidence, one treatment is more beneficial than the other?” This question is addressed by the Bayesian statistical approach and is thus more suited in this decision context. The probabilistic interpretation of Bayesian indirect treatment comparison results enables stating, taking into account all available evidence, the extent to which a hypothesis is true or false; for example, in our case the probability that apalutamide provides benefits in terms of MFS and OS compared with enzalutamide in nmCRPC patients is 74% and 83%, respectively. This approach is more relevant for clinical and reimbursement decision-making than the classic frequentist approach [25].

Current guidelines do not recommend one agent over the other for patients with nmCRPC due to the absence of head-to-head comparisons of apalutamide and enzalutamide [7,8,9]. The present results suggest that apalutamide may be associated with more favorable MFS and OS outcomes than enzalutamide. The potential difference in OS is particularly noteworthy in the nmCRPC setting, in which prolonging time to metastasis is widely viewed as the primary treatment goal [27]. The data from the current study pave the way for future studies to compare the efficacy of these agents. Ultimately, the collective body of evidence stemming from this research may help inform treatment decisions, which would benefit all patients with nmCRPC. Nevertheless, there are factors other than clinical outcomes that may affect treatment decisions, including cost-effectiveness and quality of life. Further research is warranted to evaluate these additional outcomes in patients treated with either agent.

This study is subject to limitations. As mentioned, imbalances in treatment effect modifiers can lead to violation of the assumption behind indirect comparison, which was addressed by the anchored MAIC approach. Although most clinically important baseline characteristics that may bias indirect treatment comparison results through effect modification were adjusted for, matching could only be done for characteristics reported in the PROSPER study. Therefore, it cannot be excluded that residual bias due to unmeasured confounders still exists. A direct head-to-head comparison in a clinical study would be necessary to address this potential issue and validate the findings of the present study. Between-study differences may have contributed to the OS difference observed. For example, 75.8% of SPARTAN patients received abiraterone acetate as a subsequent therapy compared with 38% of patients in PROSPER [5, 20]. The probability of one treatment being better than the other considers any difference in efficacy regardless of its clinical significance (i.e., the probability of HR < 1). Therefore, it is yet to be demonstrated whether the differences in efficacy observed in the current study would translate into meaningful clinical differences for patients. Finally, since both studies are ongoing, the present study is based on first OS results for the two studies. Further analyses will be needed to confirm the observed OS advantage of apalutamide versus enzalutamide over a longer follow-up period.

Conclusions

This indirect comparison of the efficacy of apalutamide versus enzalutamide for the treatment of nmCRPC, based on the currently available data, suggests that apalutamide is associated with a higher probability of a more favorable MFS and OS than enzalutamide.

References

Montgomery RB, Mostaghel EA, Vessella R, et al. Maintenance of intratumoral androgens in metastatic prostate cancer: a mechanism for castration-resistant tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2008;68(11):4447–54.

Beer TM, Armstrong AJ, Rathkopf DE, et al. Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(5):424–33.

Rathkopf DE, Morris MJ, Fox JJ, et al. Phase I study of ARN-509, a novel antiandrogen, in the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(28):3525–30.

Mateo J, Fizazi K, Gillessen S, et al. Managing nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2019;75(2):285–93.

Hussain M, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. Enzalutamide in men with nonmetastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(26):2465–74.

Smith MR, Saad F, Chowdhury S, et al. Apalutamide treatment and metastasis-free survival in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(15):1408–18.

American Urological Association. Clinical guidelines: castration-resistant prostate cancer 2013 amended 2018. https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer-castration-resistant-guideline. Accessed 6 Mar 2018.

Mottet N, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, et al. European Association of Urology guidelines—prostate cancer 2019. https://uroweb.org/guideline/prostate-cancer/. Accessed 15 May 2019.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology, prostate cancer—version 4.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. Accessed 1 Nov 2019.

Rozet F, Hennequin C, Beauval JB, et al. Recommandations francaises du comite de cancerologie de l’AFU—actualisation 2018–2020: cancer de la prostate. Prog Urol. 2018;28(12S):S79–130.

Bhindi B, Karnes RJ. Novel nonsteroidal antiandrogens and overall survival in nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2018;74(4):534–5.

Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, Walter SD. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(6):683–91.

Glenny AM, Altman DG, Song F, et al. Indirect comparisons of competing interventions. Health Technol Assess. 2005;9(26):1–134 (iii–iv).

Ishak KJ, Proskorovsky I, Benedict A. Simulation and matching-based approaches for indirect comparison of treatments. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(6):537–49.

Signorovitch JE, Sikirica V, Erder MH, et al. Matching-adjusted indirect comparisons: a new tool for timely comparative effectiveness research. Value Health. 2012;15(6):940–7.

Tremblay G, Chandiwana D, Dolph M, Hearnden J, Forsythe A, Monaco M. Matching-adjusted indirect treatment comparison of ribociclib and palbociclib in HR+, her2− advanced breast cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:1319–27.

Signorovitch JE, Betts KA, Reichmann WM, et al. One-year and long-term molecular response to nilotinib and dasatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia: a matching-adjusted indirect comparison. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31(2):315–22.

Sikirica V, Findling RL, Signorovitch J, et al. Comparative efficacy of guanfacine extended release versus atomoxetine for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: applying matching-adjusted indirect comparison methodology. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(11):943–53.

Tremblay G, Livings C, Crowe L, Kapetanakis V, Briggs A. Determination of the most appropriate method for extrapolating overall survival data from a placebo-controlled clinical trial of lenvatinib for progressive, radioiodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;8:323–33.

Saad F, Cella D, Basch E, et al. Effect of apalutamide on health-related quality of life in patients with non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: an analysis of the spartan randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(10):1404–16.

Dias S, Sutton AJ, Ades AE, Welton NJ. Evidence synthesis for decision making 2: a generalized linear modeling framework for pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Med Decis Mak. 2013;33(5):607–17.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Technology appraisal guidance 2017. https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/nice-guidance/nice-technology-appraisal-guidance. Accessed 6 Mar 2018.

Philippo DM, Ades AE, Dias S, Palmer S, Abrams KR, Welton NJ. NICE DSU technical support document 18: methods for population-adjusted indirect comparisons in submissions to nice: NICE; 2016. http://nicedsu.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Population-adjustment-TSD-FINAL.pdf. Accessed 1 Nov 2019.

Wallis CJD, Thenappan C, Goldberg H, et al. Advanced androgen blockage in nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: an indirect comparison of apalutamide and enzalutamide. Eur Urol Oncol. 2018;1(3):238–41.

Jansen JP, Fleurence R, Devine B, et al. Interpreting indirect treatment comparisons and network meta-analysis for health-care decision making: report of the ISPOR task force on indirect treatment comparisons good research practices: part 1. Value Health. 2011;14(4):417–28.

Mills EJ, Ghement I, O’Regan C, Thorlund K. Estimating the power of indirect comparisons: a simulation study. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e16237.

Rozet F, Roumeguere T, Spahn M, Beyersdorff D, Hammerer P. Non-metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer: a call for improved guidance on clinical management. World J Urol. 2016;34(11):1505–13.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. Coauthors employed by Janssen (J. Liu, L. Dearden, J. Sermon, S. Van Sanden, and J. Diels) were involved in study content, design, analysis, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Their authorship roles adhere to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria. The journal’s Rapid Serve Fee and Open Access publication were purchased using funding provided by the study sponsor.

Authorship

All named authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Patrick Lefebvre and Federica Torres Sakai, employees of Analysis Group, Inc., were involved in data analysis and result interpretation. Medical writing assistance was provided by Sara Kaffashian, who was an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., at the time this study was conducted. Funding for this assistance was provided by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, to Analysis Group, Inc.

Prior Presentation

Part of the material in this manuscript was presented at the ISPOR Europe 2018 Conference held from November 10–14, 2018, in Barcelona, Spain.

Disclosures

Simon Chowdhury has acted as a consultant/advisor for Astellas and Janssen and has participated in speaker bureaus for Janssen, Sanofi, Clovis Oncology, and Astellas. Stéphane Oudard has consulting roles for Astellas, Janssen, and Sanofi and has received honoraria from Bayer. Hiroji Uemura is a company consultant for Janssen, Takeda, Bayer, Astellas, and Taiho and has received company speaker honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo, MSD, Sanofi, Kyowa-Hakko Kirin, and FRI. Steven Joniau is a company consultant for Astellas, Ipsen, Bayer, Sanofi, and Janssen; has received company speaker honoraria from Astellas, Amgen, Bayer, Sanofi, Janssen, and Ipsen; has participated in studies for Astellas, Janssen, and Bayer; has received fellowship and travel grants from Astellas, Amgen, Bayer, Sanofi, Janssen, Ipsen, and Pfizer; and has received grant and research support from Astellas, Bayer, and Janssen. Jinan Liu, Lindsay Dearden, Jan Sermon, Suzy Van Sanden, and Joris Diels are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC., and stockholders of Johnson & Johnson, Inc. Dominic Pilon is an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., which has received consultancy fees from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. At the time this study was conducted, Martin Ladouceur was an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., which has received consultancy fees from Janssen Scientific Affairs LLC.; he has since moved to Evidera. Boris A. Hadaschik reports advisory roles for Bayer, Lightpoint Medical, Inc., Janssen R&D, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, and Astellas; research funding from Profound Medical, German Cancer Aid, German Research Foundation, Janssen R&D, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, and Astellas; and travel from AstraZeneca, Janssen R&D, and Astellas. Ajay S. Behl was an employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC., at the time the study was conducted; he has since moved to Novartis.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. The SPARTAN study is a Janssen-sponsored study, and all appropriate ethics approvals were granted. Data from the PROSPER study were obtained from publicly available sources. Review boards at participating institutions approved the SPARTAN and PROSPER studies, and they were conducted in accordance with the current International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Martin Ladouceur was an employee of Analysis Group, Inc. during the development of this manuscript. Ajay S. Behl was an employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs during the development of this manuscript.

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10283066.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Chowdhury, S., Oudard, S., Uemura, H. et al. Matching-Adjusted Indirect Comparison of the Efficacy of Apalutamide and Enzalutamide with ADT in the Treatment of Non-Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Adv Ther 37, 501–511 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01156-5

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01156-5